9 Implementing: Hazard Identification

This is the first of three chapters focused on managing hazards and the risks they pose to workers. In this implementation phase, safety professionals are required to enhance organisational capacity, by ensuring adequate resourcing of activities and should foster a positive safety culture, while building-up individual worker capacity through training and engagement.

In this chapter, the focus is on effective hazard identification as some hazards will be obvious, but some will be very specific to a particular task undertaken at a particular time of day, or even time of year. It is vital that organisations seek to identify hazards because they can lead to occupational disease or a WHS incident. Identifying hazards is the first step towards strengthening an organisation’s safety defence layers (see Swiss Cheese Model, Chapter 5).

Learning Objectives

This chapter introduces:

- The concept of hazard identification.

- Common hazard classifications; chemical, ergonomic, biological, physical, psychosocial, safety, and workplace.

- Strategies to identify work-related hazards and scenarios that uncover unanticipated hazards.

A hazard may be defined as “anything with the potential to harm life, health or property” (Dunn, 2012, p. 53) and, in WHS management, risk is the “likelihood and consequence of injury or harm occurring” (Standards Australia & Standards New Zealand, 2001, p. 5) due to an interaction between a hazard and a worker. Hazard identification, risk assessment and hazard controls attempt to make an organisation’s safety defence layers as strong as possible, mitigating everyday occupational health risks while reducing the likelihood of a WHS safety incident occurring. According to the Swiss Cheese Model of safety incident causation (Chapter 5), this requires management of human factors to avoid “active failures” and system-based factors, to proactively identify and address any “latent conditions”.

In blame-the-system approaches, some people are not considered innately more hazardous than others (Hopkins & Palser, 1987). Instead, it is recognised that there are situations (conditions) that increase the likelihood of human error (active failures), see Box 9.1. These conditions have been extensively researched in different fields including clinical psychology, experimental psychology, organisational psychology, educational psychology, medical science, anthropometric science, cognitive science, industrial engineering, safety engineering, and computer science (Federal Aviation Administration, n.d.). Scholars, such as Reason (2000) and Hudson (2007), have undertaken empirical studies on human factors in practice.

Box 9.1: WHS Human Factors

The following video provides a brief overview of human factors as a WHS concept.

A transcript of this video is available here.

Source: Sheridan, L. (producer, narrator) & Treadwell, L. (producer). (2019). Excerpt from Video 6: An introduction to work health and safety management.

Preston, A., audio engineer; Orvad, A., artist and Franks, R., animator, Learning, Teaching and Curriculum, University of Wollongong, Australia. YouTube

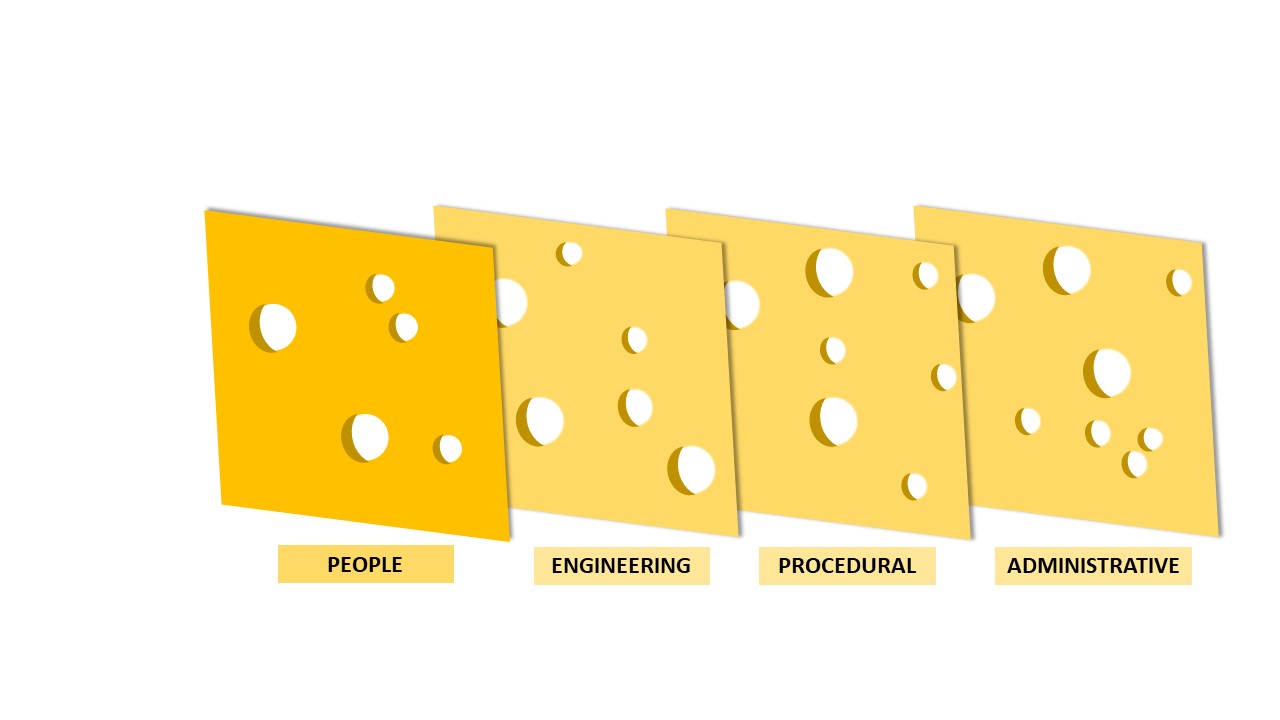

In an effective safety management system, human error would not lead to a serious incident because other safety defence layers will protect workers. Human factors mainly correspond to the ‘people’ layer of the Swiss Cheese Model (including safety culture) but require consideration of the interactions between workers and the other safety defence layers (see Figure 9.1). Just like for the other safety defence layers, human factors need be identified and controlled, however, Reason (1997) suggests this is challenging because human-centric factors are difficult to predict and control.

Figure 9.1: Swiss Cheese Model safety defence layers

Source: “Swiss Cheese Model” by Kate Thompson, CC BY 4.0

In contrast, management of latent conditions involves identifying “poor design, gaps in supervision, undetected manufacturing defects or maintenance failures, unworkable procedures, clumsy automation, shortfalls in training, less than adequate tools and equipment” (Reason, 1997, p. 10) which notionally corresponds to engineering, procedural and administrative safety defences (see Figure 9.1).

Hazard Identification

The first step in reducing the risk of a hazard to workers is to identify it. It is not possible, or appropriate, to present all possible WHS hazard identification tools and techniques here, instead, the focus will be on providing a conceptual overview.

As general rule, when establishing hazard identification processes and procedures in a business, it is advisable to:

- Use industry-specific hazard identification resources: Often available from WHS regulators or professional industry bodies, these resources identify the most common hazards associated with an industry or type of work.

- Employee engagement and consultation: First, get workers to identify hazards known to them that are specific to their role and, secondly, have them collaborate with other workers to discover the less obvious hazards that inattentional blindness or change blindness may not enable them to identify.

- Hazard identification auditing: Hire professionals, or establish mutually beneficial arrangements with suitably qualified industry peers, to independently review your work site for hazards. This strives to enact a greater level of accuracy, again seeking to avoid biases such as inattentional blindness or change blindness, and takes hazard identification to a more sophisticated level.

Note: Avoid allocating hazard identification to an accreditation body who is auditing your safety management system for two reasons; firstly, it will identify that you have weak hazard identification practices in place putting your certification in jeopardy and, secondly, these audits tend to be at a higher level and focused on system-function rather than undertaking the systematic hazard identification that is actually required for effective safety management.

Note: WHS regulators may undertake a hazard audit as part of a spontaneous site visit to your business or as part of an incident investigation; neither of these two options should be relied upon as an effective hazard identification measure as they expose the business to compliance risk. However, WHS regulators that take an educative approach (see Chapter 7 discussions on WorkSafe New Zealand as an educative WHS regulator) may genuinely support you in establishing your safety management system by undertaking a hazard audit once you have demonstrated genuine attempts at hazard identification. These WHS regulators recognise the innate vulnerability of a business at the start-up phase of safety management, where hazard controls are not yet in place, but seek to encourage an organisation’s pro-safety stance. Furthermore, your proactive engagement with the WHS regulator can be one way to demonstrate efforts towards due diligence during this challenging period.

If you are joining an established safety management system it will be important to learn both the tools that your businesses use, but also to understand why they have adopted those methods. This enables you to question if the existing tools are the best possible ones for the task.

Although definitions do vary, as a starting point, hazards maybe categorised into:

Chemical Hazards

Chemical hazards “can be a solid, liquid or gas. It can be a pure substance, consisting of one ingredient, or a mixture of substances. It can harm the health of a person who is exposed to it” (Comcare, 2021, para. 1). The International Labour Organization ranks the risk of these hazards in priority order as: “1. Asbestos, 2. Silica, 3. Heavy metals, 4. Solvents, 5. Dyes, 6. Manufactured nanomaterials (MNMs), 7. Perfluorinated chemicals (PFAS), 8. Endocrine disrupting chemicals (EDCs), 9. Pesticides, 10. Workplace air pollution” (ILO, 2021, p. v). The types of diseases that workers suffer as a consequence include respiratory illnesses, toxicity reactions, and cancer. Box 9.2 outlines the global scale and consequence of chemical hazard exposure to workers.

Box 9.2: Global perspectives on chemical hazards

Figure 9.2: A worker in full personal protective equipment handling chemicals

Source: pix4free.org, CC0

The International Labour Organization’s Exposure to hazardous chemicals at work and resulting health impacts: A global review, found that:

Workers around the world are facing a global health crisis due to occupational exposure to toxic chemicals. Every year more than 1 billion workers are exposed to hazardous substances, including pollutants, dusts, vapours and fumes in their working environments. Many of these workers lose their life following such exposures, succumbing to fatal diseases, cancers and poisonings, or from fatal injuries following fires or explosions. We must also consider the additional burden that workers and their families face from non-fatal injuries resulting in disability, debilitating chronic diseases, and other health sequela, that unfortunately in many cases remain invisible. All of these deaths, injuries and illnesses are entirely preventable.” (ILO, 2021, p. v)

Further reading:

ILO (2021) Exposure to hazardous chemicals at work and resulting health impacts: A global review. International Labour Organization.

The impact on workers of Inorganic dust can be difficult to identify due to its prolonged, rather than acute, presentation. Identifying these chemical hazards usually are a specialist activity requiring occupational epidemiologists and guidance from public health agencies and WHS regulators (see Chapter 4). Workers are involved as they may be required to participate in health monitoring, would be expected to report exposure events and, importantly, should be involved in continuous improvement of safe work procedures.

Canadian Centre for Occupational Health and Safety reflections for practitioners: “Access chemical information with substance. Find resources on chemical hazards, product safety; WHMIS [Workplace Hazardous Materials Information System], (M)SDSs [Material Safety Data Sheets], transport of hazadous materials, toxicity, and safe work practices” (2023, para 1).

Ergonomic Hazards

Ergonomic hazards are “physical factors in the environment that may cause musculoskeletal injuries” (ComCare, 2022, para. 1). Occupational therapists and ergonomists are useful in the re-design of work layouts to prevent ergonomic-related injuries (Capodaglio, 2010). In Past influencing the present we see how ergonomics for productivity has shifted to ergonomics for health.

Figure 9.3: Safe manual handling can involve team work.

Source: “Team lifting” by California Department of Industrial Relations, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0

Past influencing the present

Frederick Taylor used scientific principles (Scientific Management) to change the positioning of workers and machines in the workplace to enhance productivity and Henry Ford built on this by designing the assembly line, which brought the task to the worker rather than the workers to the task (see Chapter 3).

Figure 9.4: An automobile assembly in from 1923 in the United States.

Source: “The Automobile Industry – 1923” via Jasperdo, flickr.com, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

Today industrial engineers continue the traditions of Scientific Management by striving to identify efficiencies through industrial design (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2023) but ergonomists and occupational therapists focus on designing work for workers, including personalising the workplace (see Figure 9.5), particularly if a person is returning to work after illness or injury (Ammendolia et al., 2009).

Figure 9.5: John Pentikis undertakes a work station adjustment

Source: Fort George G. Meade Public Affairs Office, flickr.com, CC BY 2.0

Canadian Centre for Occupational Health and Safety reflections for practitioners: “Ergonomics is matching the job to the worker and product to the user. Access information and resources on workplace design and considerations, work-related musculoskeletal disorders, related risks, and helpful exercises” (2023, para. 2).

Biological Hazards

Biological hazards “are organic substances that present a threat to the health of people and other living organisms. Biological hazards include “viruses…toxins from biological sources, spores, fungi, pathogenic, micro-organisms, bio-active substances” (ComCare, 2023, para. 1). These types of hazards can be acute, and have an immediately obvious impact on health, or lead to chronic conditions (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2022) which are “defined broadly as conditions that last 1 year or more and require ongoing medical attention or limit activities of daily living or both” (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2022, para. 1).

In an Australian survey, 19% of workers had biological hazards present at their workplace; 75% of these workers were exposed to human biological hazards and 30% to animal biological hazards. Less was known about exposure of workers to less obvious hazards such as plants or mould (Safe Work Australia, 2020).

Canadian Centre for Occupational Health and Safety reflections for practitioners: “Many workplace hazards have the potential to harm workers’ short- and long-term health, resulting in diseases, disorders and injuries” (2023, para. 3).

Physical Hazards

America’s Centers for Disease Control and Prevention define physical hazards as “workplace agents, factors, or circumstances that can cause tissue damage by transfer of energy from the agent to the person” (2022c, para. 1). If only thinking about the Swiss Cheese Model, workers might only identify physical hazards with acute impacts on workers, such as an object striking a worker and breaking their arm, but the transfer of energy aspect of the above definition can refer to many other situations. One example (see Figure 9.6) is workers operating tools or machinery that vibrate as “excessive exposure can affect the nerves, blood vessels, muscles and joints of the hand, wrist and arm causing Hand-Arm Vibration Syndrome” (Health and Safety Executive, n.d.-a, para. 17).

Figure 9.6: Two workers jackhammering a hard floor

Source: pickpik.com, pikipik free licence

Physical hazards comprise a broad range of hazards including “loud noises, extreme pressures, magnetic fields, radiation, fire, poor lighting, unsafe machinery, misused machinery, obstructions in walkways, [and] slippery floors” (National Association of Safety Professionals, 2018, para. 11). They can be challenging to identify at times because piece of workplace machinery might always pose a physical safety risk but slippery floors are a temporary physical hazard.

Canadian Centre for Occupational Health and Safety reflections for practitioners: “Physical hazards are substances or activities that threaten your physical safety. They are the most common and are present in most workplaces at one time or another. These include unsafe conditions that can cause injury, illness and death” (2023, para 4).

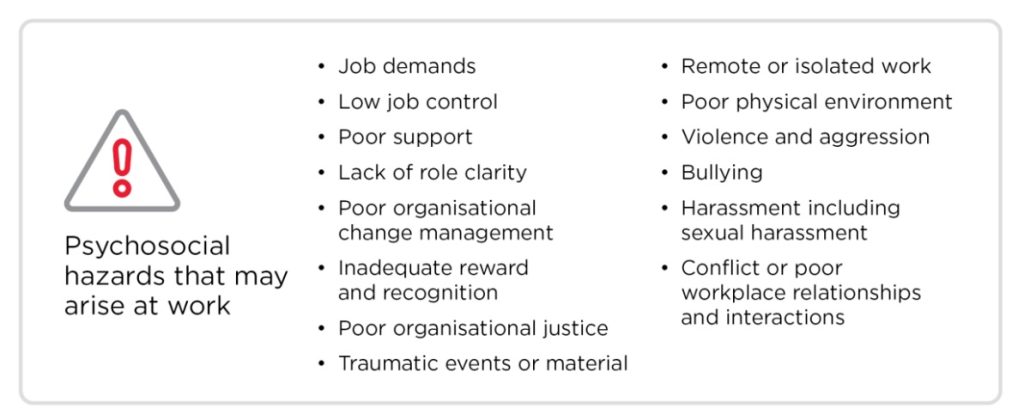

Psychosocial Hazards

Psychosocial hazards are “aspects of work which have the potential to cause psychological or physical harm” (ComCare, n.d., para. 1). The Australian Government has classified 14 types of psychosocial hazards (see Figure 9.7) and these are important to manage because:

Psychological injuries have longer recovery times, higher costs, and require more time away from work. Managing the risks associated with psychosocial hazards not only protects workers, it also decreases the disruption associated with staff turnover and absenteeism, and may improve broader organisational performance and productivity. (Safe Work Australia, 2022, p. 5)

Essentially, while overlooked until recently, psychosocial hazards represent an important business risk that must be addressed.

Figure 9.7: Psychosocial hazards

Source: Safe Work Australia (2022, p. 5), CC BY-NC 4.0

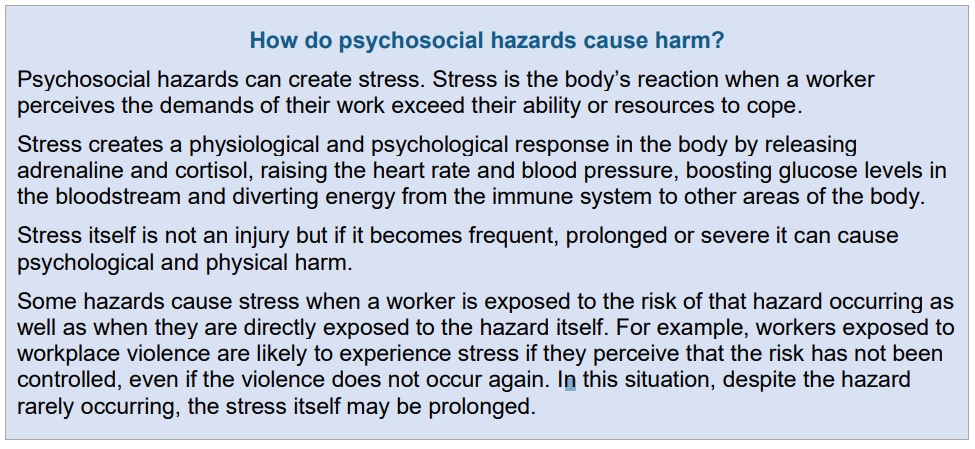

What makes psychosocial hazards so harmful that their recovery is prolonged? Safe Work Australia explain the biochemistry behind the physical harm triggered by psychological harm:

Source: Safe Work Australia (2022, p. 5), CC BY-NC

Different industries expose workers to different types of psychosocial hazards. WorkSafe Queensland highlight manufacturing, transport, agriculture, construction, retail and wholesale, and healthcare as particularly ‘at risk’ industries.

In healthcare, for example, workers have low job control as their work comprises shiftwork and the provision of care to patients in challenging circumstances. There are high job demands, with considerable emotional control required to enable service delivery. There can be poor levels of support with care staff working very independently. Low role clarity can emerge because of the autonomy of the role and limited opportunities for supervisory guidance and feedback. Workplace change is constant as each shifts changes the care team and allocated patients. There can be poor perceptions of institutional justice around shift allocations or inconsistent implementation of procedures. Finally, poor relationships can develop, with conflict not being resolved between shifts, or the line between professional and personal being blurred in patient care (WorkSafe Queensland, 2020). In Chapter 5, Neil Logan (Box 5.1) spoke of the psychosocial hazards of aged care, including personal attachment to elderly people who will inevitably pass away.

In addition to industry-based differences, distinct segments of worker population can be disproportionally exposed to psychosocial hazards (Lovelock, 2019). In 2021 a national survey of the New Zealand working population (n = 3612) identified on average that 35% had been exposed in the prior year to ‘offensive behavour’ including bullying (23%), cyberbullying (16%), violent threats (14%), sexual harassment (11%), and physical violence (11%). Colleagues and/or customers could be perpetrators of psychosocial hazards. However, within this same survey, Māori and Pacific workers reported higher levels of exposure to psychosocial hazards comparable to the entire New Zealand worker population. For example, bullying was experienced by Māori and Pacific at a rate of 28%, compared to 23%, and physical violence was reported by 17%, versus 11% of respondents (Khieu et al., 2021). Global populations experience psychosocial hazards at different rates as well, for example violence at work is more likely to be experienced by women than men (see Box 9.3).

Box 9.3: Violence and harassments in the workplace

Source: “Violence and Harassment in the Workplace” by the International Labour Organization via Soundcloud

Canadian Centre for Occupational Health and Safety reflections for practitioners: “Learn about stress, violence, bullying, and other behaviours in the context of a workplace environment” (2023, para 5).

Safety Hazards

Safety hazards comprise hazards that may not easily fall into the above categories but do create conditions that lead to safety incidents, and according to America’s National Association of Safety Professionals are:

Tripping and slipping hazards, including spilled liquid, cords running across the floor and blocked aisles. Working from any raised work area, including roofs, scaffolding and ladders. Moving machinery parts and unguarded machinery that a worker can accidentally touch. Electrical hazards, including improper wiring, missing ground pins and frayed cords. Confined spaces. Hazards related to machinery, including boiler safety and the improper use of forklifts. (National Association of Safety Professionals, 2018, para. 22)

One safety hazard that requires particular attention is working alone which is “work is done in a location where the employee can’t physically see or talk to other staff members” (Ministry of Business, Employment and Innovation, n.d.c, para. 1). This can occur both within a workplace (see Working Alone Example 1) and outside of workplace, given PCBUs are responsible for work wherever it is being undertaken (NZ Parliament, 2015; Safe Work Australia, 2023). Identifying hazards in potentially unknown worksites poses significant challenges (see Working Alone Example 2).

Working Alone Example 1: In a workplace setting

In Australia in 2013, Mr Vijay Singh died from organ failure, caused by hypothermia, after being trapped in a commercial freezer. He was inadvertently working alone when his co-workers all went on lunch break without him (Coroner NSW, 2015). The Swiss Cheese Model of safety incident causation is applied to this incident below.

Active Failure:

- Mr Singh has poorly manoeuvred the forklift truck when moving stock into a freezer, leading to him being trapped in the freezer by products and the forklift truck.

Figure 9.7: Loading stock into confined spaces, particularly if chilled, requires training and personal protective equipment

Source: “Man Riding a Yellow Forklift lifting Boxes” by Elevate, pexels.com, CC0

Latent conditions:

- Mr Singh was hired via a labour hire company to pack products. A job change led to him using a forklift and working in the commercial freezer without additional training.

- While the company had a forklift policy, Mr Singh did not have a forklift licence. Different staff members assumed that another had checked that Mr Singh had a forklift licence.

- The incident occurred on a Saturday. The site did not usually operate on a Saturday, there were fewer staff than usual, and the main supervisor left the site at 12.30pm.

- Mr Singh became a lone worker, but this was unintentional. The three other packers on site went on a lunch break together at approximately 1.30pm and returned to work at 2pm.

- The other workers decided to finish for the day at 2.30pm and realised they had not seen Mr Singh. It was at this point that they discovered Mr Singh trapped in the freezer and called emergency services. They tried to turn off the freezer but did not know how and the company was not answering their phones (as it was a non-standard workday).

In this case, there are administrative errors, such as not checking for a valid forklift truck licence, through to procedural ones around working in freezers. Moreover, the emergency response procedures were lacking also with the workers being unable to turn off the freezer and the company not being available by telephone to advise them how.

Ironically, less than an hour earlier there had been a near miss. Mr Singh had poorly manoeuvred the forklift truck and called for help. All the workers then collaborated to re-align and free-up the forklift, which had become stuck in the freezer. Sadly, once working alone, that one remaining layer of safety defence (access to the other workers) was not available and Mr Singh’s calls for help went unheard, leading to his death.

Working Alone Example 2: Outside of a workplace setting

The disappearance of real estate agent Yanfei Bao, on the 19th July 2023 in Christchurch New Zealand, has raised concerns for lone workers undertaking work outside of workplace settings.

Figure: A real estate agent is showing a property to a client

Source: RDNE stock project, pexels.com, pexels free licence

Ms Bao was door-knocking to expand her client base. Unfortunately, while undertaking this work activity, she was abducted and, after some hours, her car was found abandoned in a suburb different to where she was doing her work. A person was arrested for murder despite her still being missing (Radio New Zealand, 2023).

Off-site client engagement is common in real estate work, according to the Real Estate Institute’s Jen Baird, it is “a fairly standard part of real estate, and lots of people still do it and do it perfectly safely. It’s a great way to meet people and engage with their communities” (Radio New Zealand, 2023, para. 5). The challenge is then how to ensure a workers can undertake this activity safely and, if not, whether a PCBU can expect a worker to engage in this activity.

Workplace Hazards

The Canadian Centre for Occupational Health and Safety (2023) uses this category to classify some hazards that do not easily fit within other categories but are workplace related including indoor air quality, scents or odours, weather (temperatures, lighting and storms) etc.

In concluding, the overall purpose of hazard assessment is to produce an exhaustive register of work-related hazards, no matter where that work occurs. Once this has been established, the next required step is to determine the risk associated with each hazard and this is achieved via risk assessment.

A hazard may be defined as "anything with the potential to harm life, health or property" (Dunn, 2012, p. 53).

"Likelihood and consequence of injury or harm occurring” (Standards Australia & Standards New Zealand, 2001, p. 5).

“A culture that supports an organization’s OH&S management system is largely determined by top management and is the product of individual and group values, attitudes, managerial practices, perceptions, competencies and patters of activities that determine commitment to, and the style and proficiency of, its OH&S management system” (Standards Australia and Standards New Zealand, 2018), p. 27).

"Hazard identification is part of the process used to evaluate if any particular situation, item, thing, etc. may have the potential to cause harm" (CCOSH, 2023, para. 4).

Occupational disease is “any illness associated with a particular occupation or industry. Such diseases result from a variety of biological, chemical, physical, and psychological factor that are present in the work environment or are otherwise encountered in the course of employment” (Kazantzis, 2022, para. 1).

In the WHS context, “An incident is an unplanned event or chain of events that results in losses such as fatalities or injuries, damage to assets, equipment, the environment, business performance or company reputation” (Wolters Kluwer, n.d., para. 1).

"James Reason proposed the image of "Swiss cheese" to explain the occurrence of system failures...According to this metaphor, in a complex system, hazards are prevented from causing human losses by a series of barriers. Each barrier has unintended weaknesses, or holes – hence the similarity with Swiss cheese. These weaknesses are inconstant – i.e., the holes open and close at random. When by chance all holes are aligned, the hazard reaches the patient and causes harm" (Perneger, 2005, p. 71).

"Theories about the causes of industrial accidents can be classified into two broad types: those which emphasize the personal characteristics of the workers themselves and those which locate the causes in the wider social, organisational or technological environment. The former approach is conveniently termed blaming-the-victim and the latter, blaming the-system" (Hopkins & Palser, 1987, p. 26).

"Inattentional blindness is a popular human error associated with selective attention or inattention. It can be depicted as an individual’s failing to notice or recognize a visual object or event due to a lack of active attention in a given situation" (Park et al., 2022, p. 1),

"Failing to notice significant changes to visual scenes...understanding the inability or failure to detect change is critical to improving worker safety (Solomon et al., 2021, p. 1).

"Auditing is defined as the on-site verification activity, such as inspection or examination, of a process" (ASQ, 2023, para. 1).

Accreditation is formal authorisation by an standards organisation permitting the accredited entity (person or business) to certify other businesses against their standards (United Kingdom Accreditation Service, n.d.).

Certification is the auditing of a business, by an independent accredited entity, to demonstrate (certify) its compliance with standards set by a standards organisation (United Kingdom Accreditation Service, n.d.).

In principle, and in accordance with the Australian Model Work Health and Safety Bill, a regulator is a legally established government body whose functions are:

“ (a) to advise and make recommendations to the Minister and report on the operation and effectiveness of this Act;

(b) to monitor and enforce compliance with this Act;

(c) to provide advice and information on work health and safety to duty holders under this Act and to the community;

(d) to collect, analyse and publish statistics relating to work health and safety;

(e) to foster a co-operative, consultative relationship between duty holders and the persons to whom they owe duties and their representatives in relation to work health and safety matters;

(f) to promote and support education and training on matters relating to work health and safety;

(g) to engage in, promote and co-ordinate the sharing of information to achieve the object of this Act, including the sharing of information with a corresponding regulator;

(h) to conduct and defend proceedings under this Act before a court or tribunal;

(i) any other function conferred on the regulator by this Act”

(Safe Work Australia, 2023, section 152).

“Compliance risk primarily arises in industries and sectors that are highly regulated” (Kenton, 2022, para. 9).

"The care that a reasonable person exercises to avoid harm to other persons or their property" (Merriam-Webster, n.d., para. 1).

"Particles in the air may cause lung problems...Inorganic refers to any substances that do not contain carbon" (John Hopkins Medicine, n.d., para. 6).

"Occupational epidemiology has the same main goal as the broad field of epidemiology: to identify the causes of disease in a population in order to intervene to remove them. Occupational epidemiology is an exposure-oriented discipline; it is thus the systematic study of illnesses and injuries related to the workplace environment" (Merletti et al., 2014, p. 1577 citing Checkoway et al. 2004).

“Public health is the science and art of preventing disease, prolonging life, and promoting physical health and efficiency through organized community efforts for the sanitation of the environment, the control of community infections, the education of the individual principles of personal hygiene, the organization of medical and nursing service for the early diagnosis and preventative treatment of disease, and the development of the social machinery which will ensure to every individual in the community a standard of living adequate for the maintenance of health” (Windslow, 1920, p. 30)

"Standard Operating Procedure (SOP) sometimes called a Safe Operating Procedure, outlines a set of detailed instructions to help workers perform complex tasks properly and safety. Having standard operating procedures in place means workers don't have to guess what to do next and can perform tasks efficiently and without danger to themselves or others. Failure to follow SOPs may cause significant safety breaches or loss in production and operational efficiency" (Safety Culture, n.d., para. 1).

"Occupational therapy is the art and science of helping people take part in everyday living through their occupations" (Occupational Therapy Board of New Zealand, n.d., para. 1)

Note: Occupation in this context is not limited to the occupations of work and employment.

"Someone who studies the design of furniture or equipment and the way this affects people's ability to work effectively" (Cambridge Dictionary, 2023, para. 1).

Scientific Management may be defined as: “An approach to management, based on the theories of F.W. Taylor, dealing with the motivation to work. It sees it as a manager’s duty to find out the best way to do a given job, by a process of work measurement, then give each worker individual instructions which have to be strictly followed. The individual is thus seen as the extension of his or her machine, and his or her rewards are also to be allocated mechanically, with more pay expected to produce more output regardless of any other factors” (Statt, 1999, p. 150).

"Industrial engineers devise efficient systems that integrate workers, machines, materials, information, and energy to make a product or provide a service" (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2023, para. 1).

"Human beings contribute to the breakdown of such [complex technological] systems in two ways. Most obviously, it is by errors and violations committed at the 'shape end' of the system...Such unsafe acts are likely to have a direct impact on the safety of the system and, because of the immediacy of their adverse effects, these acts are termed active failures" (Reason, 1997, p. 10).

"Fallibility is an inescapable part of the human condition, it is now recognized that people working in complex systems make errors or violate procedures for reasons that generally go beyond the scope of individual psychology. These reasons are latent conditions....poor design, gaps in supervision, undetected manufacturing defects or maintenance failures, unworkable procedures, clumsy automation, shortfalls in training, less than adequate tools and equipment - may be present for many years before they combine with local circumstances and active failures to penetrate the system's many layers of defences" (Reason, 1997, p. 10).

Near misses are "unplanned incidents that occurred at the workplace that, although not resulting in any injury or disease, had the potential to do so” (Archer et al., 2015, p. 86). When contextualised in the Swiss Cheese Model of incident causation, they can be understood as "an event that could have potentially resulted in…losses, but the chain of events stopped in time to prevent this” (Wolters Kluwer, n.d., para. 1).