8 Establishing: Compliance competency

Identifying the WHS-related legislation and regulations that organisations must comply with in their jurisdiction, is a critical step in establishing a safety management system. While legislation is “a law or set of laws suggested by a government and made official by a parliament” (Cambridge Dictionary, n.d., para. 1), regulations “are rules made by a government or other authority in order to control the way something is done or the way people behave” (Collins Dictionary, n.d., para. 1). It is the regulations that establish the role of any WHS regulator, as an enforcer of WHS legislation.

Learning Objectives

This chapter introduces:

- The objectives of the Australian Model Work Health and Safety Bill, which underpins both Australian and New Zealand WHS legislation.

- PCBU obligations specific to managing hazards and risks, worker consultation and worker education.

- Regulation and the role of the WHS regulator.

- Worker compensation rights in Australia and New Zealand.

Legislation

In Australia, since the 1970s, there have been calls for a uniform approach to WHS legislation between all states and territories, with unions seeking to ensure equitable nation-wide safety benchmarks for workers, and all levels of government seeking to enhance business productivity through streamlining of WHS expectations for companies (Windholz, 2013). In 2009 a national review, involving extensive consultation with employer groups, WHS regulators, legal experts, and worker representatives (unions), recommended an “optimal structure and content of a model OHS [WHS] Act that was capable of being adopted in all [Australian] jurisdictions” (Safe Work Australia, n.d.-a, para. 9).

By April 2010, a committee comprised of workplace relations ministers from federal and state jurisdictions endorsed a model bill—a prototype draft—that could be presented in each jurisdiction and, in due course, be passed legislation. This collaborative piece of work became known as the Model Work Health and Safety Bill. At October 2023 all jurisdictions, except the State of Victoria, have implemented legislation fundamentally derived from the Model Act (Department of Employment and Workplace Relations, 2023). Table 8.1 summarises each Australian jurisdiction’s WHS legislation, WHS regulator, and workers’ compensation entity.

Table 8.1: Summary of WHS legislation and regulators across Australian jurisdictions

Source: AIMS Industrial (n.d., para. 15).

As each Australian jurisdiction is different, nuanced changes—distinct from Model Act— have been made when it has been legislated. Box 8.1. contains resources that enable comparison of legislation between Australian jurisdictions with regards to their implementation of key elements of the Model Act.

Box 8.1: Safe Work Australia’s comparative legislation resources

Safe Work Australia summarises WHS Acts across Australia’s jurisdictions, these can be obtained by visiting their Law and Regulation website.

Safe Work Australia compares interpretations of the Model Act between state and territory legislation, it is available via a downloadable file on their Model WHS Laws website.

In New Zealand, a 2013 WHS taskforce concluded that “New Zealand’s work health and safety system was failing” (WorkSafe, 2019a, para. 3). This timing coincided with Australia’s WHS legislative reformation and harmonisation efforts. New Zealand adopted many elements from Australia’s Model Work Health and Safety Bill in it’s Health and Safety at Work Act 2015, with careful adaptations for the New Zealand context (WorkSafe, 2019a). To this end, Australia and New Zealand safety legislation share a common objective which is articulated in Box 8.2.

Box 8.2: The objective of the Work Health and Safety Act 2011 (Cth) s3

3.(1) The main object of this Act is to provide for a balanced and nationally consistent framework to secure the health and safety of workers and workplaces by:

(a) protecting workers and other persons against harm to their health, safety and welfare through the elimination or minimisation of risks arising from work; and

(b) providing for fair and effective workplace representation, consultation, co-operation and issue resolution in relation to work health and safety; and

(c) encouraging unions and employer organisations to take a constructive role in promoting improvements in work health and safety practices, and assisting persons conducting businesses or undertakings and workers to achieve a healthier and safer working environment; and

(d) promoting the provision of advice, information, education and training in relation to work health and safety; and

(e) securing compliance with this Act through effective and appropriate compliance and enforcement measures; and

(f) ensuring appropriate scrutiny and review of actions taken by persons exercising powers and performing functions under this Act; and

(g) providing a framework for continuous improvement and progressively higher standards of work health and safety; and

(h) maintaining and strengthening the national harmonisation of laws relating to work health and safety and to facilitate a consistent national approach to work health and safety in this jurisdiction.

Note: As replicated in Health and Safety at Work Act 2015 (New Zealand) s.3.

In practice, PCBUs responding to the legislative requirements are mostly involved in:

- Managing hazards and risks: Keep workers, and other persons, safe from work or workplace derived harm (subsection a)

- Consulting on health and safety: Ensure worker consultation within the business is fair and effective (subsection b) and that engagement with employer and worker representative bodies (unions) is constructive (subsection c)

- Educating on health and safety: Ensure workers are informed and capable (education and training) to undertake their WHS responsibilities, as corresponding to their roles (subsection d)

Subsection (e) refers to the establishment of a WHS regulator to enact compliance with the Act, and subsection (f) builds in checks and balances to ensure the appropriate enactment of legislation by regulators so they do not breach their powers. Subsection (g) states that continuous improvement is imperative (this supports a systems-based approach to safety management). Finally, and only specific to Australia, is the goal expressed in subsection (h) of unifying national WHS legislation through adoption of the Model Act.

PCBU obligations to manage hazards and risks will be the focus of Chapter 9: Hazard Identification, Chapter 10: Risk Assessment, Chapter 11: Hazard Control, and Chapter 12: Emergency Response, as compliance with subsection (a) comprises the majority of an organisation’s WHS management activities. Consulting and educating on health and safety will be explained briefly here but, more importantly, will be contextualised within Chapters 9 to 12, given this is when these interventions would roll out. Subsequent to this, the discussion will explain the role of regulations and, specifically, the WHS regulator and any legislated or regulated bodies that enact worker compensation rights.

Consulting on Health and Safety

What comprises worker consultation that fulfils the legal and moral requirements of WHS management? Good safety consultation:

Enables workers to respond and contribute to issues that directly affect them, and provide valuable information and insights. It’s a two-way process where information and views are shared between PCBUs and workers. PCBUs can become more aware of hazards and issues experienced by workers, and involve them in finding solutions or addressing problems. (Safe Work South Australia, n.d, para. 8)

Consultation can range from extensively planned strategies for complex organisations, through to hazard and risk-based chats in smaller, lower risk, settings. The extent of worker consultation that is reasonably practicable is determined by factors such as:

-

the size of the business and how it is structured,

-

the way work is arranged and where workers are located,

-

what suits workers – ask your workers how they would like to be consulted and consider their needs, and

-

the complexity, frequency and urgency of the issues that require consultation. (Safe Work Australia, n.d.-b, para. 1)

For due diligence purposes, the terms of reference and composition of any committees should be documented along with minutes of meetings that capture any safety concerns raised and, in subsequent meetings, how these were addressed in a reasonably practicable manner. As such, staff need to be aware that they are fulfilling an obligation under the WHS legislation, so the PCBU and workers should take this responsibility seriously.

Businesses should consult with workers regarding safety because “workers often notice issues and practices, or foresee consequences, that might otherwise be overlooked” (Safe Work South Australia, n.d, para. 8), leading to better overall hazard identification (see Chapter 9), risk assessment (see Chapter 10), and hazard control (see Chapter 11) i.e. safety outcomes. As Reason (1997) points out, when endorsing a flexible culture, it is important that the people who do the task, and know it well, are those who are most empowered to control its safety management. From Dekker’s perspective, it is only through having worker-driven WHS that safety can actually ever be achieved (Dekker, 2018).

So genuine attempts to consult with workers will ensure representation of workers from all parts of the business and across all work shifts (Safe Work Australia, n.d.-b); this will be further explored across Chapters 9–12 in examples, such as, Risk Assessment Example 1: Exposure to sunlight (and Glastonbury Festival!) in Chapter 10.

Educating on Health and Safety

Organisations have a legislated (legal) responsibility to inform, educate, and train workers regarding their safety rights and responsibilities; it is useful to understand the obligations of inform, educate and train specifically.

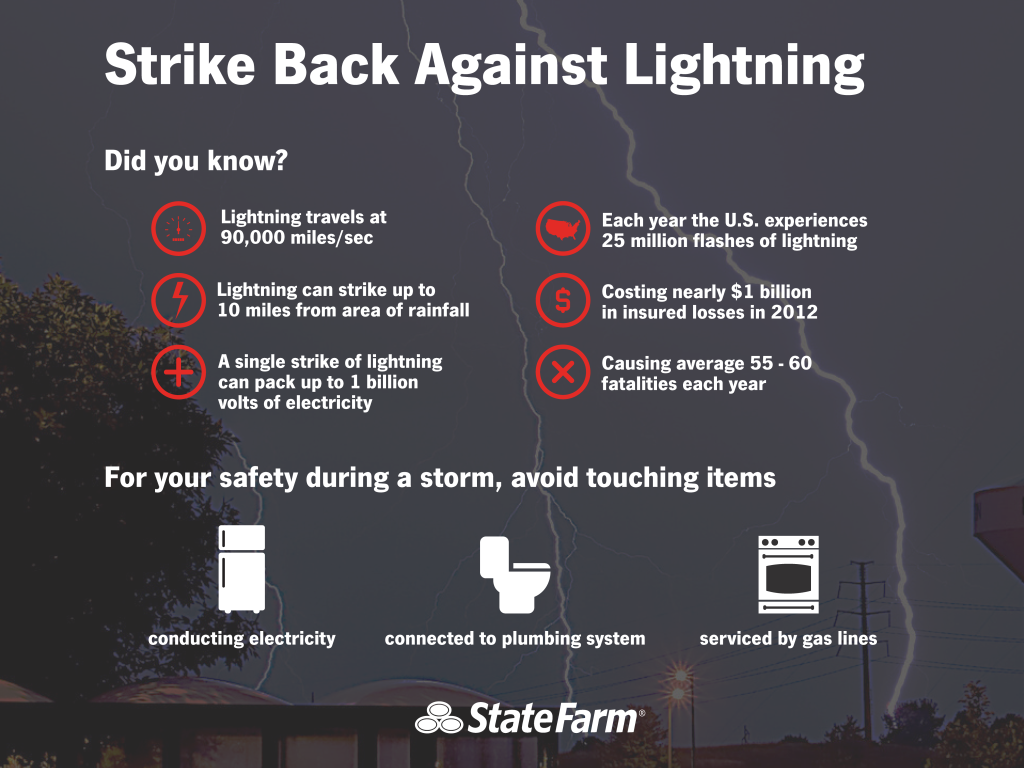

To inform is to “impart knowledge of some particular fact, occurrence, situation, etc.” (Oxford English Dictionary, n.d.-a, part 1.2). This communication is likely in one direction, from the organisation to the worker. The inform-ation will predominantly be top-down, generated centrally and broadly across the organisation (see Figure 8.1). From an HR perspective, informing can occur when:

- Inducting a worker to a workplace, including when they change roles or sites, to ensure they are aware of relevant organisational policies and procedures as part of due diligence.

- Keeping workers up to date on safety initiatives or safety outcomes. This supports an organisation’s learning culture but also reinforces its reporting culture as workers will see how their reporting of data generates safety initiatives.

Figure 8.1: An informational communication

Source: “Lightning Safety infographic” by State Farm, flickr.com, CC BY 2.0

To educate is to “help or cause (a person, the mind, etc.) to develop the intellectual and moral faculties in general; to impart wisdom to; to enlighten” (Oxford English Dictionary, n.d.-b, part 5). The goal of educate is ambitious as it seeks to establish awareness to evoke cognitive and behavioural change (Arlinghaus & Johnson, 2018). In the WHS management context, education will predominately involve adults, which likely requires two-way engagement between the educator, as an organisational representative, and workers, the participants in the course, to enable learning that encourages individuals to change their perceptions or perspectives. This moral and behavioural aspect is particularly important if the educational intervention seeks to establish or align workers with the organisation’s desired safety culture (see Box 8.3). From an HR perspective, education is likely to take place:

- Prior to hiring an employee, if formal studies are required to be eligible for recruitment into a specific role.

- As part of a worker’s continuing professional development by an external tertiary education provider, or run internally if tailored to address organisational issues or work conditions.

Box 8.3: Educating workers on the importance of safety

This video uses humour to educate workers that a poor attitude towards safety management practices leads to incidents. Cleverly, it leads the viewer to expect one type of hazard to be a potential source of harm but swaps it out for a less expected one.

Source: “Funny Workplace Safety Training Video” by Chanel 1 Creative Media, YouTube

To train is to “subject to discipline and instruction for development of character, behaviour, or skill” (Oxford English Dictionary, n.d.-c, part 11.10). Training is developing a specific skill to achieve targeted competency. From an HR perspective, training can include:

- Familiarising a worker with machinery to ensure their competency (due diligence). A new recruit may have used a different model at their prior workplace or training institution, or, if the organisation upgrades machinery, all operators will require re-training.

- Familiarising a worker with a new job role to ensure competency (due diligence), such as when they transition to become a supervisor.

Legislative requirements to inform, educate and train are designed to pre-emptively strengthen an organisation’s safety defence layers (see Swiss Cheese Model, Figure 5.1). To achieve this, every worker must be, and stay, informed. Education can happen without training, for example this publication is an educational, not a training, resource. While training can occur without education, this is strongly cautioned against. A worker who has the skill to operate a machine, without any intellectual or moral understanding of safety, is vulnerable to an incident. Only pathological and reactive businesses (see Figure 6.2; Hudson’s Safety Culture Ladder) would train without educate, whereas generative businesses would never separate safety education from training.

Box 8.4: Why a safety education is important

The following video demonstrates workers who competently know how to operate a piece of machinery (they are trained) but clearly have not been educated on its use.

Source: “1st go around on the excavator” by QuicKsilver7537, YouTube

To achieve subsection (a), protecting workers and others from harm (see Box 8.2), the potential role of information, education and training in an organisation is embedded in further discussions of hazard identification (Chapter 9), risk assessment (Chapter 10) and hazard control (Chapter 11), and is central to the enactment of and emergency response (Chapters 12). The effectiveness of inform, educate and train should be evaluated, as required by subsection (g), as part of continuous improvement (Chapter 13).

Regulation and the WHS regulator

Legislation is delegated as regulations to a minister or government department. These entities are then responsible for monitoring and, when necessary, updating the regulations (Parliament Counsel Office, n.d.). Legislation establishes the WHS regulator, an entity responsible for implementation of fines and penalties as specified in the regulations (see Box 8.5, where the role of a WHS regulator is defined in Australia). Essentially, WHS regulators are responsible for ensuring an organisation’s due diligence.

In New Zealand, the WHS regulator is WorkSafe who consider that their job:

Isn’t just about compliance with the rules. We also aim to promote and embed positive health and safety practices around the country, and to do this, we collaborate with persons conducting a business or undertaking (PCBUs), workers, health and safety representatives, and industry bodies.” (WorkSafe, 2018, para. 3)

This educative, versus punitive, approach recognises the innate challenge that WHS regulators face; there is always likely to be more businesses requiring inspection than inspectors available to conduct visits. This was even the case during the British Industrial Revolution when the Health and Morals of Apprentices Act of 1802 was introduced, but only four inspectors were employed to inspect over 4000 mills (see Chapter 2). Moreover, it makes sense that regulators would be more effective if they focus on shifting reactive or calculative organisations up Hudson’s Safety Culture Ladder (see Figure 6.2), rather than solely focusing on pathological businesses. Box 8.5 defines the role of the WHS regulator, as implemented in full from the Model Health and Safety Bill, in the Australian federal legislation.

Box 8.5: Establishment of a regulator’s role in the Work Health and Safety Act 2011 (Cth) S 152.

In Australia, a WHS regulator is a legally established government body whose functions are:

(a) to advise and make recommendations to the Minister and report on the operation and effectiveness of this Act;

(b) to monitor and enforce compliance with this Act;

(c) to provide advice and information on work health and safety to duty holders under this Act and to the community;

(d) to collect, analyse and publish statistics relating to work health and safety;

(e) to foster a co-operative, consultative relationship between duty holders and the persons to whom they owe duties and their representatives in relation to work health and safety matters;

(f) to promote and support education and training on matters relating to work health and safety;

(g) to engage in, promote and co-ordinate the sharing of information to achieve the object of this Act, including the sharing of information with a corresponding regulator;

(h) to conduct and defend proceedings under this Act before a court or tribunal;

(i) any other function conferred on the regulator by this Act.

In practice, PCBUs will engage with their WHS regulator in some of the following ways:

- Collaborating: Working together to enhance worker safety through exchanging information on occupational health issues (see Chapter 4) or best practice hazard and risk assessment.

- Inspecting: Receiving a site visit and this can include unannounced workplace inspections if potential safety breaches have been reported by a whistle-blower (see Box 8.6).

- Notifying: Reporting on scheduled or completed work as required by legislation; or reporting on their hazardous substances; or notifying illnesses, injuries or incidents (see Box 8.7).

- Investigating: Receiving a site visit specifically designed to investigate active failures and latent conditions (causes) of a WHS incident to determine if safety management was reasonably practical or negligent.

- Prosecuting: Defending due diligence against accusations of negligence in a court of law.

Box 8.6: Oregon Occupational Safety and Health work site inspection

In this video, a WHS regulator site inspection coincides with an incident.

Source: “Trench Cave In | Oregon OSHA compliance officer caught cave in on tape” by Oregon Occupational Safety and Health, YouTube

Box 8.7: What is a notifiable incident?

A notifiable incident is an incident that must be reported to the WHS regulator and are usually “occurrences that resulted in a fatality, permanent disability or time lost from work of one day/shift or more” (Archer et al., 2015, p. 86). For example, WorkSafe in New Zealand expects to be informed of a death, serious illness or injury, or any incidents associated with work, and defines a notifiable incident as “where someone’s health or safety is seriously endangered or threatened” (WorkSafe, n.d., para. 4). Notification is for serious situations including amputation, serious head injury, serious eye injury, a serious burn, skin separating from tissue, a spinal injury, loss of a bodily function, serious lacerations, exposure to an injury or illness requiring treatment within 48 hours, contracting a serious infection (particularly if associated with a known workplace biological hazard), and illnesses for specific work sites (i.e. mining), as scheduled in regulations. Note: Different legislations can have different jurisdictions. In New Zealand, incidents related to work aboard ships are reported to Maritime New Zealand, that industry’s safety regulator rather than WorkSafe.

Both WHS regulators and PBCUs should strive to engage via collaboration. Investigations and prosecution are very undesirable given it likely involves a tragic incident and, from the organisation’s perspective, is associated with considerable business risk. Box 8.8 contains a short news podcast on an investigation undertaken when two port workers died within a week of each other at two different ports in New Zealand.

Box 8.8: Regulatory non-compliance at NZ ports

This Radio New Zealand news podcast discusses the findings of a Transport Accident Investigation Committee report into the deaths of Atiroa Tuaiti (Port of Auckland) and Don Grant (Port of Lyttelton) in 2022 which identified poor regulatory compliance and a need for industry-wide safety standards.

Figure 8.2: Lyttleton Port

Source: “Port Lyttleton. NZ” by Bernard Spragg, flickr.com, CC0

Select image to listen (opens in a new tab)

Source: “Investigation into deaths of port workers finds industry safety issues” by Krystal Gibbens, Radio New Zealand Checkpoint, 21st October 2023 (see Checkpoint, 2023)

While poor regulatory compliance does exist, there are businesses that choose to go above and beyond compliance and adhere to voluntary compliance initiatives, such as those endorsed by the United Nations as is now discussed in Past Influencing the Present.

Past influencing the present

The International Labour Organization was created by the Treaty of Versailles in 1919 , but is now a specialist organisation of the United Nations, devoted to “advancing opportunities for women and men to obtain decent and productive work in conditions of freedom, equity, security and human dignity” (International Labour Organization, n.d.-a). They achieve their goals through alliances with member-states (national governments) who sign conventions that governments then uphold through voluntary compliance demonstrated via voluntary reporting. In this way, the International Labour Organization strives to influence national legislation to protect worker rights, including their safety, and therefore indirectly influence organisations.

Figure 8.4: Logo, International Labour Organization

Source: © International Labour Organization, used with permission

New Zealand was a founding member of the International Labour Organization and, by passing the first legislation enabling women to vote in 1893 and later laws to restrict working hours, is recognised as critical to establishing a foundational international Hours of Work (Industry) Convention, 1919 (International Labour Organization, n.d.-b). As the Ministry of Business, Employment and Innovation explain, International Labour Organization conventions are ratified by the New Zealand government and a “tripartite partnership of government, employers and workers is fundamental to New Zealand’s ILO activities. A tripartite delegation attends the annual International Labour Conference and all reporting to the ILO is undertaken on a tripartite basis” (Ministry of Business, Employment and Innovation, n.d.-a, para. 3); enactment of international conventions is via national-level collaboration between government, industry/employer professional bodies and unions. All actions are, however, voluntary.

While Australia and New Zealand have both ratified the International Labour Organization’s Protocol 2014 to the Forced Labour Convention of 1930, only Australia has implemented a corresponding piece of modern slavery legislation. Even then, the Modern Slavery Act 2018 [Australia] only requires compliance by organisations with revenues over $100 million per year and, for most businesses, reporting is voluntarily.

In New Zealand, non-governmental organisations continue to advocate for modern slavery legislation using the convention as a lever, for example World Vision’s report Risky Goods: New Zealand Imports (World Vision, 2021). The Ministry of Business, Employment and Innovation suggests that future legislation would:

Require all organisations to take action if they become aware of modern slavery or worker exploitation; Medium and large organisations would be required to disclose the steps they are taking; Large organisations and those with control over New Zealand employers would be required to undertake due diligence.” (Ministry of Business, Employment and Innovation, n.d.-b, para. 3)

So, again, different levels of organisations will have different requirements to either comply, or voluntarily comply, with modern slavery initiatives.

Overall, the International Labour Organization has an important role in highlighting issues and trends associated with worker labour and safety rights worldwide. Together with broader United Nation initiatives, including the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (with Goal 3 Good Health and Wellbeing and Goal 8 Decent Work and Economic Growth being specific to WHS management), this organisation creates a social impetus for legislative and voluntary compliance and sets expectations for organisations’ social licence to operate.

Worker Compensation Rights Regulation

In many jurisdictions, legislation will afford workers the right to be compensated for any work-derived injury or illness. This ‘workers’ compensation’ emerged as a response to limitations in British common law that previously required employees to sue for compensation (see the following Past Influencing the Present for more details). The goal of most modern workers’ compensation schemes is to ensure that workers, who offer their labour to an employer, are compensated for the costs of any illness or injury associated with the provision of their labour.

In turn, employers pay levies into a scheme that should seek to fairly compensate worker costs, without exposing the business to safety liability (Safe Work Australia, 2011). The WHS regulator, rather than workers, retains the capacity to prosecute businesses for safety negligence (see Box 8.5). Moreover, levies can incentivise good safety practice as payments can be reduced according to “a good record of managing worker safety and recovery at work” (Icare, n.d.).

Where possible, the goal for all parties in workers’ compensation schemes is that the worker return to work because this is good for business but, importantly, for workers as “work is one of the most effective ways to improve wellbeing” because it supports “participation, independence and social inclusion” (Comcare, 2023a, para. 2).

Past influencing the present

In early 20th Century Britain, the unions formally became involved in the political system through the Fabian Society founding the British Labour Party (Fabian Society, n.d.). In the United States this was not the case and this fragmented efforts towards achieving workers’ compensation rights (Guyton, 1999). The British government established the Employer’s Liability Act 1880 whereby the “employer had a general duty to take reasonable care to select competent employees and not to expose workers to unreasonable risks such as directing the use of a dangerous machine or unsafe work conditions” (Veljanovski, 2021, p. 661). This was followed by the Workmens’ Compensation Act 1897, a ‘no-fault’ approach to managing compensation (Guyton, 1999). Subsequently, the Fabian Society—through the British Labour Party—enacted a universal healthcare system in Britain (Fabian Society, n.d.) which now works alongside workplace compensation schemes that today ensure British workers are compensated for work injuries (UK Parliament, n.d.-a).

In the United States, this ‘care’ for workers was achieved through lobbying for Worker’s Compensation and emerged as the Federal Employee’s Compensation Act 1916 (Norlund, 1991). “All U.S. workers’ compensation programs are the products of the American Industrial Revolution” (Nordlund, 1991, p. 3). Historically caring for injured workers, or the families of deceased workers, was undertaken by the local communities, most often through their churches. The scale of the Industrial Revolution, and the migration of workers away from their communities, meant this was no longer a tenable approach (Nordlund, 1991). After observing European efforts to ensure the welfare of workers and their families (particularly that of Germany which set up the first scheme), in 1916 the United States established an act for federal employees to include “compensation for all civil employees of the Federal Government injured or killed in the performance of duty” (Nordlund, 1991, p. 7). It compensated work-derived injury and disease. However, it exempted employers from being sued for negligence and poor safety conditions (Guyton, 1999).

Even today, as influenced by their histories, different countries’ jurisdictions will tend more towards a universal health approach or adhere strictly to workers’ compensation schemes. As we will now find out, New Zealand has a more universal health approach and Australia has a workers’ compensation scheme.

Worker compensation rights in New Zealand

New Zealand has a universal coverage approach to injury:

If someone in New Zealand has an accident and we cover their injury, we use this money to help pay for and support their recovery. This includes treatment, health, rehabilitation and support services, loss of income or financial help and injury prevention in the community. (Accident Compensation Corporation, 2018, para. 2)

This coverage applies to anyone who incurs an injury, including visitors, within New Zealand (see Box 8.9). This compensation is administered via the Accident Compensation Corporation (ACC).

Box 8.9: ACC New Zealand: Who we are

This video outlines the role of the ACC in administering New Zealand’s universal accident coverage scheme.

Source: “ACC New Zealand: Who we are” by ACC New Zealand, YouTube

Unlike overseas workers’ compensation schemes, where levies may be solely collected from businesses, in New Zealand the accident compensation scheme is funded via a broad base including business, income, fuel and vehicle levies, and broader government funded via tax. However, like in other workers’ compensation schemes, business premiums are linked to business safety performance with a poor claims record leading to higher levies (Accident Compensation Corporation, 2018). While having universal accident cover can be considered positive, in the context of workplace health and safety it is noted by WorkSafe that “New Zealand has high rates of workplace fatalities, serious harm injuries, and work related illness compared to other OECD [Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development] member countries” (WorkSafe, 2023, para. 2). This infers that the accident compensation scheme may be so (cost) effective that it may inadvertently be leading to an over-reliance on prosecution to address business safety negligence.

In contrast to worker’s compensation schemes, there is no coverage provided for worker illness and “every year, more than 100,000 New Zealanders are made redundant, laid off, or have to stop working because of a health condition or a disability” (Ministry of Business, Employment and Innovation, 2022, p. 4). Those who lose their jobs can experience considerable disadvantage if not eligible for redundancy payments or welfare therefore, in 2022, the New Zealand Government put out a discussion document to consider if an income insurance scheme might be viable to introduce (Ministry of Business, Employment and Innovation, 2022).

Worker compensation rights in Australia

In Australia, workers receive compensation for “medical treatment, rehabilitation or time off to recover after being injured at work” (Health Direct, 2021, para. 2). It also provides compensation for those who have a work-acquired occupational disease (Health Direct, 2021). Notably, “to be eligible, workers only have to prove that their injuries were work related—they do not need to prove negligence on the part of an employer” (Safe Work Australia, 2011, p. 5). This means it only addresses workplace illness or injuries (unlike the accident cover in New Zealand), but still embeds a ‘no fault’ (no blame-the-victim or blame-the-system) approach.

Australian-based workers’ compensation are managed as insurance schemes and “under Australian law, employers must have insurance to cover their workers in case they get sick or injured because of work” (Safe Work Australia, n.d.-c, para. 1). Businesses pay levies that are calculated according to the risk their industry poses to workers and worker compensation claims are linked to the specific business (Icare, n.d.). The compensation to workers can include some wages while recovering, medical costs (including those associated with rehabilitation or care being provided), lump sums for permanent disability (to enable reasonable adjustments around home), or compensation to families in the case of a fatality (Safe Work Australia, 2011).

PCBU engagement with compensation schemes

In practice, PCBUs will engage with the compensation regulator, or their delegated insurer, in some of the following ways when an employee is injured:

- Registering: Confirm that the effected worker is registered with the scheme to ensure their medical care is sufficient and all costs are compensated.

- Administrating: Provide any required details, and process any relevant documents, to enable the worker’s care.

- Monitoring: Engage with the compensation body to monitor the progress of recovery and stay engaged with your worker(s) to enhance their wellbeing.

- Collaborating: Working together with the compensation body, occupational health professionals and the worker to develop a return to work plan to make reasonable adjustments so they can work until their full, if possible, recovery.

This chapter has broadly outlined the compliance expectations established by the Model Work Health and Safety Bill (Safe Work Australia, n.d.-a), which has subsequently been brought into law via legislation in all jurisdictions, except for the State of Victoria, and in New Zealand. This chapter is not designed to replace the ‘compliance’ checking phase of any organisation’s safety management system but, instead, it seeks to explain the rationales behind the act, some of the implications for practice and to cite reliable information sources that could be accessed and further considered.

With compliance notionally understood, implementation will be the focus on the next five chapters which will move step-by-step through hazard identification, risk assessment, and determining what hazard controls are reasonably practicable before, finally, designing emergency responses enabling workers to escape safely as a final safety defence layer.

“A law or set of laws suggested by a government and made official by a parliament” (Cambridge Dictionary, n.d., para. 1).

"Regulations are rules made by a government or other authority in order to control the way something is done or the way people behave" (Collins Dictionary, n.d., para. 1).

“The power, right, or authority to interpret and apply the law…the limits or territory within which authority may be exercised” (Merriam-Webster, n.d., para. 1).

In principle, and in accordance with the Australian Model Work Health and Safety Bill, a regulator is a legally established government body whose functions are:

“ (a) to advise and make recommendations to the Minister and report on the operation and effectiveness of this Act;

(b) to monitor and enforce compliance with this Act;

(c) to provide advice and information on work health and safety to duty holders under this Act and to the community;

(d) to collect, analyse and publish statistics relating to work health and safety;

(e) to foster a co-operative, consultative relationship between duty holders and the persons to whom they owe duties and their representatives in relation to work health and safety matters;

(f) to promote and support education and training on matters relating to work health and safety;

(g) to engage in, promote and co-ordinate the sharing of information to achieve the object of this Act, including the sharing of information with a corresponding regulator;

(h) to conduct and defend proceedings under this Act before a court or tribunal;

(i) any other function conferred on the regulator by this Act”

(Safe Work Australia, 2023, section 152).

"Good consultation enables workers to respond and contribute to issues that directly affect them, and provide valuable information and insights. It’s a two-way process where information and views are shared between PCBUs and workers. PCBUs can become more aware of hazards and issues experienced by workers, and involve them in finding solutions or addressing problems. Workers often notice issues and practices, or foresee consequences, that might otherwise be overlooked. PCBUs must genuinely consult with workers and their representatives, including HSRs, before any changes or decisions are made that may affect their health and safety. Consultation should take place during both the initial planning and implementation phases so that everyone's experience and expertise can be taken into account" (Safe Work SA, 2023, para. 8).

Australia's Model Work Health and Safety Bill defines reasonably practicable as:

"In this Act, reasonably practicable, in relation to a duty to ensure health and safety, means that which is, or was at a particular time, reasonably able to be done in relation to ensuring health and safety, taking into account and weighing up all relevant matters including:

(a) the likelihood of the hazard or the risk concerned occurring; and

(b) the degree of harm that might result from the hazard or the risk; and

(c) what the person concerned knows, or ought reasonably to know, about:

(i) the hazard or the risk; and

(ii) ways of eliminating or minimising the risk; and

(d) the availability and suitability of ways to eliminate or minimise the risk; and

(e) after assessing the extent of the risk and the available ways of eliminating or minimising the risk, the cost associated with available ways of eliminating or minimising the risk, including whether the cost is grossly disproportionate to the risk" (WorkSafe Australia, 2023, Section 18).

"The care that a reasonable person exercises to avoid harm to other persons or their property" (Merriam-Webster, n.d., para. 1).

James Reason conceptualises a safety culture as comprising “four critical subcomponents of a safety culture: a reporting culture, a just culture, a flexible culture and a learning culture” (Reason, 1997, p. 196). By focusing on the development of these individual subcomponents, he believes that a safety culture will emerge as “ways of doing, thinking and managing that have enhanced safety health as their natural byproduct” (Reason, 1997, p. 192).

"Used to refer to a situation in which decisions are made by a few people in authoriy, rather than by the people who are affected by the decisions" (Cambridge Dictionary, n.d, para. 1).

“A culture that supports an organization’s OH&S management system is largely determined by top management and is the product of individual and group values, attitudes, managerial practices, perceptions, competencies and patters of activities that determine commitment to, and the style and proficiency of, its OH&S management system” (Standards Australia and Standards New Zealand, 2018), p. 27).

"James Reason proposed the image of "Swiss cheese" to explain the occurrence of system failures...According to this metaphor, in a complex system, hazards are prevented from causing human losses by a series of barriers. Each barrier has unintended weaknesses, or holes – hence the similarity with Swiss cheese. These weaknesses are inconstant – i.e., the holes open and close at random. When by chance all holes are aligned, the hazard reaches the patient and causes harm" (Perneger, 2005, p. 71).

In the WHS context, “An incident is an unplanned event or chain of events that results in losses such as fatalities or injuries, damage to assets, equipment, the environment, business performance or company reputation” (Wolters Kluwer, n.d., para. 1).

"Intended as a punishment" (Cambridge Dictionary, n.d, para. 1).

"On the simplest level, a whistleblower is someone who reports waste, fraud, abuse, corruption, or dangers to public health and safety to someone who is in the position to rectify the wrongdoing. A whistleblower typically works inside of the organization where the wrongdoing is taking place; however, being an agency or company “insider” is not essential to serving as a whistleblower. What matters is that the individual discloses information about wrongdoing that otherwise would not be known" (National Whistleblowers Center, 2023, para. 3).

"Human beings contribute to the breakdown of such [complex technological] systems in two ways. Most obviously, it is by errors and violations committed at the 'shape end' of the system...Such unsafe acts are likely to have a direct impact on the safety of the system and, because of the immediacy of their adverse effects, these acts are termed active failures" (Reason, 1997, p. 10).

"Fallibility is an inescapable part of the human condition, it is now recognized that people working in complex systems make errors or violate procedures for reasons that generally go beyond the scope of individual psychology. These reasons are latent conditions....poor design, gaps in supervision, undetected manufacturing defects or maintenance failures, unworkable procedures, clumsy automation, shortfalls in training, less than adequate tools and equipment - may be present for many years before they combine with local circumstances and active failures to penetrate the system's many layers of defences" (Reason, 1997, p. 10).

"Negligence, in law, the failure to meet a standard of behaviour established to protect society against unreasonable risk" (Encyclopaedia Britannica, 2023, para. 1).

Business risk may be defined as "the exposure a company or organization has to factors that could lower its profits or lead it to fail” (Kenton, 2022, para. 1).

"The act of obeying a particular rule or law, or of acting according to an agreement without being forced to" (Collins Dictionary, n.d., para. 1).

"The United Nations is an international organization founded in 1945. Currently made up of 193 Member States, the UN and its work are guided by the purposes and principles contained in its founding Charter. The UN has evolved over the years to keep pace with a rapidly changing world. But one thing has stayed the same: it remains the one place on Earth where all the world’s nations can gather together, discuss common problems, and find shared solutions that benefit all of humanity (United Nations, 2023, para. 1).

The Treaty of Versailles is a “peace document signed at the end of World War I by the Allied and associated powers and by Germany in the Hall of Mirrors in the Palace of Versailles, France, on June 28, 1919” (Encyclopaedia Britannica, 2023, para. 1).

"Modern slavery is a relationship based on exploitation. It is defined by a range of practices that include: trafficking in persons; slavery; servitude; forced marriage; forced labour; forced marriage, debt bondage; deceptive recruiting for labour or services; and the worst forms of child labour and is visible in many global supply chains. Each of these terms is defined in treaties and documents of the United Nations and the International Labour Organization" (Australian Human Rights Institute, 2019, para. 3)

"The social license to operate (SLO), or simply social license, refers to the ongoing acceptance of a company or industry's standard business practices and operating procedures by its employees, stakeholders, and the general public. The concept of social license is closely related to the concept of sustainability and the triple bottom line" (Kenton, 2023, para. 1).

“Workers’ compensation, commonly referred to as “workers’ comp,” is a government-mandated program that provides benefits to workers who become injured or ill on the job or as a result of the job. It is effectively a disability insurance program for workers, providing cash benefits, healthcare benefits, or both to workers who suffer injury or illness as a direct result of their jobs” (Kagan, 2023, para. 1).

"The act of officially accusing someone of committing and illegal act by brining a case against that person in a court of law" (Cambridge Dictionary, n.d, para. 1).

Occupational disease is “any illness associated with a particular occupation or industry. Such diseases result from a variety of biological, chemical, physical, and psychological factor that are present in the work environment or are otherwise encountered in the course of employment” (Kazantzis, 2022, para. 1).

"Theories about the causes of industrial accidents can be classified into two broad types: those which emphasize the personal characteristics of the workers themselves and those which locate the causes in the wider social, organisational or technological environment. The former approach is conveniently termed blaming-the-victim and the latter, blaming the-system" (Hopkins & Palser, 1987, p. 26).

"Theories about the causes of industrial accidents can be classified into two broad types: those which emphasize the personal characteristics of the workers themselves and those which locate the causes in the wider social, organisational or technological environment. The former approach is conveniently termed blaming-the-victim and the latter, blaming the-system" (Hopkins & Palser, 1987, p. 26).

Occupational health had its modest beginnings in first aid and disease controls for high risk heavy industry workplaces, such as mines, but gained greater recognition in the 1970s when the World Health Organization acknowledged its contribution to the identification of workplace-derived factors causing occupational illness and suggested its remit should be broadened to encompass public health. So, today, many occupational health specialists have more of a public health, and less of an immediate workplace, focus (Schilling, 1989).

"A return to work program is a workplace’s written plan that focuses on finding meaningful and suitable work for workers coming back to the workplace from injury or illness. The program should include prevention, accommodation, and support for recovery. Through collaboration, the goal of the program is to have the worker return to their pre-injury or pre-illness job, where appropriate, and in a timely manner. The return to work program outlines the roles and responsibilities of all parties involved. It is a guideline for developing individualized plans for both physical and mental injuries. Return to work programs can also be used to facilitate accommodations for non-work-related injuries" (Canadian Centre for Occupational Health and Safety, n.d., para. 1).

“Reasonable adjustments are changes an employer makes to remove or reduce a disadvantage related to someone's disability. For example: making changes to the workplace, changing someone's working arrangements, finding a different way to do something, providing equipment, services or support. Reasonable adjustments are specific to an individual person. They can cover any area of work“ (Advisory, Conciliation and Arbitration Service, 2022, para. 1).

Note: Disability can be permanent or temporary.

In the Australian legal context:

"The concept of reasonable adjustments reflects the understanding that a worker with an injury, ill health or disability can often

perform tasks if adjustments are made to accommodate the effects of their injury, ill health or disability. The aim of any reasonable adjustment is to minimise the impact of the injury, health problem or disability to enable the worker to fully take part in work-related programs and effectively undertake the inherent requirements of their job.

Workers face many obstacles to participating in a life in work. Reasonable adjustments that support someone’s ability to work can be effective in:

> preventing deterioration of health and allowing employees with health problems to stay at work

> enabling employees to stay at work or return to work after injury

> assisting people with a disability to enter and stay in the workplace" (ComCare, 2013, para. 1).

"Hazard identification is part of the process used to evaluate if any particular situation, item, thing, etc. may have the potential to cause harm" (CCOSH, 2023, para. 4).

"The purpose of risk assessment is to identify and manage hazards to reduce the likelihood of incidents occurring" (ACC, 2012, p. 52).

Hazard control is determining "...appropriate ways to eliminate the hazard, or control the risk when the hazard cannot be eliminated" (Canadian Centre for Occupational Health and Safety, n.d., para. 6).