3 Industrial Revolution in the United States from 1793 until the early 20th Century

The beginning of the United States’ Industrial Revolution is attributed to an English immigrant opening a textile mill in Rhode Island in 1793 (Weightman, 2007). Like in Britain, mass industrialisation and production followed, but in America, a labour shortage led to more union activity and a greater emphasis on productivity. This, in turn, led to studies of management and, more specifically, scientific management.

Learning Objectives

By the end of this chapter, we will have explored:

- The unique circumstances within the United States and how these influenced industrialisation in this new nation.

- The role of the American Civil War, and its anti-slavery movement, in generating a labour shortage which enabled worker collectives to establish.

- The emergence of Taylorism, Scientific Management and Fordism as employer responses to managing worker productivity in the face of labour shortages and labor union movement strikes.

The European master-apprentice model transferred from Britain, via its colony, to America. By 1792, craft guilds, such as the Association of Shoemakers in Philadelphia, were already establish (Freeman, 2020). British craftspeople dominated the British labour market well into the British Industrial Revolution because their collective movements fought to protect skilled (trade or craft) worker rights (Walling, 1905). In America, the labour market transition was swifter and, for example, master craftsmen dominated Boston’s labour market in 1790 but were considerably outnumbered by journeymen (unskilled day labourers) by 1815 (Tomlins, 1993).

Walling’s (1905) explains that in the American context reduced demand for skilled workers was paired with an inflow of less skilled workers. The emphasis in America came to be on skilled and unskilled workers associating to collectively negotiate better conditions. While initially, displaced skilled craftspeople comprised the membership of worker collectives, by the middle of 1800s unions for everyone were forming in mining, railroads, and factories because “many workers saw the development of these kinds of unprecedented concentrations of wealth as threatening not just their employment situation but the very nature of American democracy” (Freeman, 2020, para. 6). This said, similar to in Britain, there were also paternalistic employers who were innovative in their approaches towards workers, Lowell Mills (see Box 3.1) is one such example.

Box 3.1: Lowell Mills

In 1814, a mill opened in Massachusetts whose operation was to be based in the Protestant work ethic. Francis Cabot Lowell and his Boston Associates decided to overcome potential labour shortages by offering work to women. “For many of the mill girls, employment brought a sense of freedom. Unlike most young women of that era, they were free from parental authority, were able to earn their own money, and had broader educational opportunities” (Gilder Lehrman Institute, 2023, para. 3). Lowell insisted that, in addition to housing, the young women be provided with an education. However, it is also important to recognise that hiring an all-female workforce was good financial decision with their lower wages.

Figure 3.1: The Lowell Mill

Source: “Mills in Lowell, Massachusetts” by Timothy Dexter, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 3.0

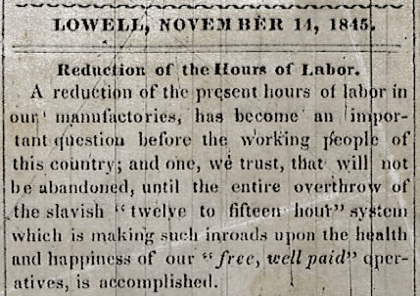

When conditions changed in the 1830s, a drop in the price of textiles meant that the Lowell Mills sought to cut wages. The ‘mill girls’ successful went on strike against the decision and, as a result, sustained their wage. They came to form the First Union of Working Women (American Federation of Labor, 2023). The Lowell Mill girls are also renown for reducing their six day, 75 hour week, down to a ten-hour day (see Figure 3.2) as part of the ten-hour day movement (Nicholson, 2004).

Figure 3.2: Lowell ‘mill girls’ lobby for a ten hour day

Source: Voice of Industry Project, Public Domain

To contextualise this, by 1835 Boston Artisans were lobbying against long work hours with paternalist employers (likely the Boston Associates who were also involved in the Lowell Mill). These skilled craftspeople fought for the ten-hour day by refuting arguments of Protestant-ethic employers that these workers would “spend all our hours of leisure in drunkenness and debauchery if the hours of labor are reduced” (cited in Irving & Schwaab, 1952, p. 342–343). Some success came in 1840 when President Martin Van Buren, by executive order, “directed the observance of the ten-hour system for laborers and mechanics employed on the [federal] government’s public works” (Kelly, 1950). However, it took until 1847 for the first state legislated ten-hour day for non-government workers and this took place in the State of New Hampshire. The New Hampshire legislation, although not strictly enforced, demonstrates the influence of Lowell Mill girls on their geographical region and overall on the United States Labor Movement (American Federation of Labor, 2023). Interestingly, 1847 is when the British Ten Hours Act was introduced (Encyclopaedia Britannica, 2023).

Past influencing the present

Have you ever considered how the Industrial Revolution impacts on our lives today?

When a school bell rings, it seems normal and timeless that school students will collect their belongings and move on to their next class. However, many facets of modern life are, in fact, based on practices established by the Industrial Revolution. For example, using a school bell to signal a shift in activity or the start of a lunch break, is based on a factory model of education (Shaw, 2016, para. 1).

In response to the tight control of their working hours (and lives) women of the Industrial Revolution wrote poems of protest, such as The Factory Bell, as “The bells woke the operatives up, called them into the mills; they rang at breakfast, called them back into the mills, again at lunch, at closing time, and finally at curfew” (Voice of Industry Project, 2012, para. 3).

The power of the collective in America was strengthened by a labour shortage induced by the emancipation of slavery. In 1803, as calls to emancipate slaves increased in the northern states:

The United States [federal government] abolished the international slave trade [importation of slaves], creating a labor shortage. Under these circumstances, the domestic slave trade increased as an estimate one million enslaved people were sent to the Deep South [southern states of the United States] to work in cotton, sugar and rice fields.” (Elliott & Hughes, 2019, para. 14)

The American Civil War (1861–1865), fought on abolishing slavery altogether (see Abraham Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation, Figure 1.8), stimulated manufacturing which then required more workers (Clinton, 2008) but concurrently removed males from the labour force, as they became soldiers (or even casualties), therefore reducing the available working population (Clinton, 2008). Increased taxes, taken by government to pay for the war, led to inflation which, in turn, encouraged workers to organise to increase their wages to protect their standard of living (Commons, 1918). The conclusion of the war then abruptly removed slave labour, leading to a complete restructuring of economies in the southern states (Ransom, 1989), which exacerbated the existing labour shortage and would, post-war, empower the union movement. Notably these uniquely American conditions were quite a distinct from the British Industrial Revolution experiences given their rapidly growing British population had provided a ready source of workers thereby thwarting attempts by workers to collectively negotiate better wages and conditions.

Collective worker groups, even those devastated by the Civil War, rapidly reformed when subsequent peace-time industrialisation occurred. In 1865, William Sylvis had high ambitions for these newly formed collectives to combine into a national union so as to influence government laws on labour (Commons, 1918; Foner, 1947). As leader of the National Union of Iron Molders, he wrote to the Ship Caulker’s union saying, “what we need is a Department of government attending exclusively to Labor matters, with its head in the president’s Cabinet to speak for us” (cited in Lombardi, 1942, p. 19). Union lobbying for this cause appears to have been somewhat successful as, in 1867, Congress established the Committee on Education and Labor (Committee on Education and the Workforce, 2023). However, this committee had a wide gamut, ranging from addressing the emergence of industry, through to post Civil War developments, such as the establishment of an education system as a means to integrate former African American slaves into mainstream society, particularly for the employment options education could afford them (McKinney, 2013). When Sylvis headed the National Labor Union (1866–1873) he “placed its reliance primarily on legislative action” as opposed to the “economic coercion” of traditional labour unions (Lombardi, 1942, p. 17). When he died in 1869, however, the legislative approach discontinued as he’d been its driving force (Lombardi, 1942).

Despite their existence, unions were not formally endorsed and their economic coercion approach (strikes) led to a period of violent clashes between organised workers and those who sought to quell their ‘illegal’ activities. “Between 1875 and 1910, state militias – which is what today we would call the National Guard – were called out nearly 500 times to deal with labor unrest” (Freeman, 2020). In response, in 1883, the Committee on Education and Labor was specifically charged with addressing labour unrest across the country (McKinney, 2013). One outcome of that year’s sitting of the Committee was the establishment of the Bureau of Labor Statistics, and this was followed in 1888 by a Bureau of Labor (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2023). Notably, neither of these entities reach Sylvis’ aspirations; they were not directly overseen by the U.S. President (Lombardi, 1942).

In the context of a labour shortage, and strengthening union activity, employer approaches to the ‘management of labour’ emerge—these are the origins of the modern discipline of management. As a “result of the rapid and chaotic growth of many organizations, it became clear that a more systematic approach to management was needed” Witzel (2011, p. 6–7). Henry Towne was an American engineer who, in 1886, wrote:

The organization of production labour must be directed and controlled by persons having not only good executive ability, and possessing the practical familiarity of a mechanic or engineer with the goods produced and the processed employed, but having also, and equally, a practical knowledge of how to observe, record, analyze and compare essential facts in relation to wages, supplies, expense accounts, and all else that enters into or affects the economy of production and the cost of the product. (Towne, 1986)

While echoing Adam Smith’s assertion that efficiency could further unlock the economic potential of industrial production, this statement was designed to validate the role of industrial engineers in the ‘management’ of production workers and was a call to action, to which American engineer Frederick Taylor responded via his conceptualisation of Scientific Management.

Scientific Management may be defined as:

An approach to management, based on the theories of F.W. Taylor, dealing with the motivation to work. It sees it as a manager’s duty to find out the best way to do a given job, by a process of work measurement, then give each worker individual instructions which have to be strictly followed. The individual is thus seen as the extension of his or her machine, and his or her rewards are also to be allocated mechanically, with more pay expected to produce more output regardless of any other factors. (Statt, 1999, p. 150)

It is the practical use of scientific methods, gained from the Scientific Revolution, to enhance production outcomes amidst the rapid changes derived from industrialisation.

Frederick Taylor read Henry Towne’s 1886 article and, after garnering considerable workplace experience, presented his own perspective in 1895 focused on rewarding employees based on the work performed, rather than the hours worked. He justified his stance with scientific data derived from undertaking:

Time trials with a stopwatch, measuring how long it took workers to perform tasks, and set up a small department to record and analyse the results. By creating a run of data through these time studies, Taylor was able to arrive at optimum times for each task. (Witzel, 2011, p. 85)

Taylor felt paying workers for the work they achieved was the fairest way to compensate their labour while maximising production.

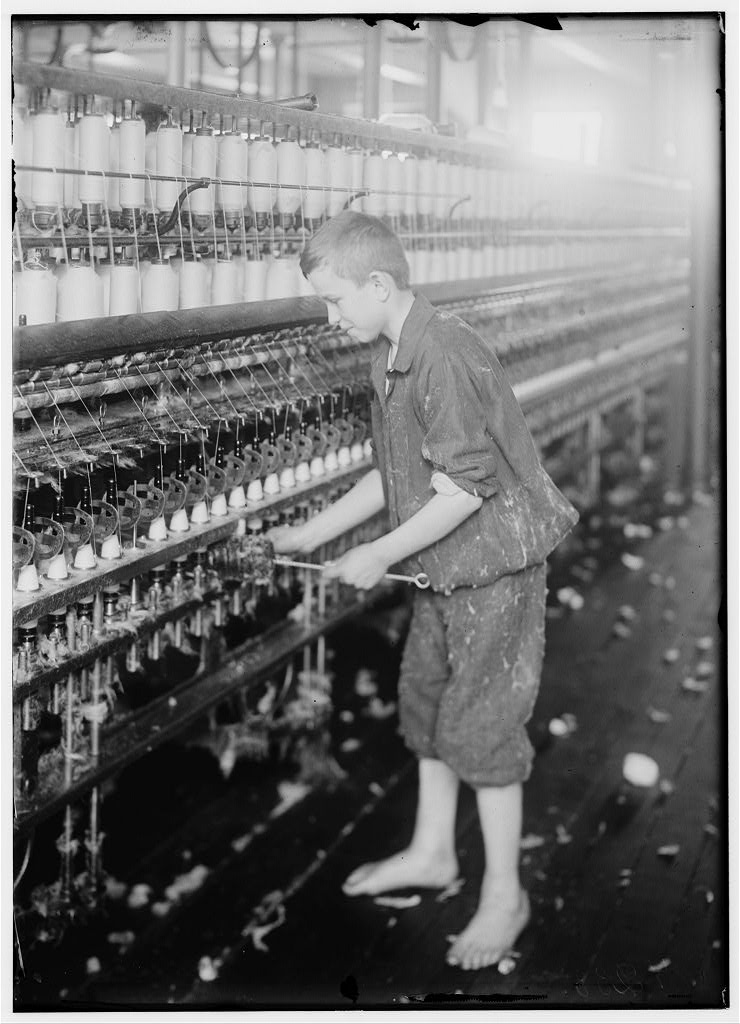

However, unions had long advocated “A fair day’s wages for a fair day’s work”—a popular slogan used by worker collectives since philosopher Thomas Carlyle coined it in 1843 (Carlyle, 1843, p. 17). Taylor was arguing that what comprises a fair day’s work should be determined through Scientific Management as he felt that many unions deliberately had their members work slower on day pay rates (McKelvey, 1952, p. 15). Around the same time, public awareness on the conditions of workers was increasing due to the efforts of people such as sociologist Lewis Hines who, using a camera (see Figure 3.3), sought to capture the experiences of the working class, including the plight of child labourers, to create awareness among the general population on the human cost behind the increasingly affordable products they were purchasing (Sutherland, 2012).

Figure 3.3: Spinners and doffers in Mollahan Mills, Newberry, South Carolina, December 1908

Source: “Spinners and doffers in Mollahan Mills. Many others as small. Newberry, S.C.” by Lewis Hine, Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain

While Taylor’s pay-per-piece did incentivise the worker to produce more (Thompson, 1913), unions continued to raise concerns about the injuries to workers caused by fast, repetitive, work. At the 1911 American Federation of Labor convention, their President Samuel Gompers stated, “organized labor would always be hostile…to any system which ruined the worker’s health and lowered wages by substituting unskilled for skilled operatives” (McKelvey, 1952, p. 17). However, Taylor’s approach to timing staff, and paying the most efficient workers more, was popular with business owners and production supervisors as it provided a credible and logical response to collective (union) pay claims—you get paid for what you do—but, from this point, The International Association of Machinists and the American Federation of Labour became “implacable enemies of Scientific Management” (Nelson, 1992, p. 9)—more money per piece did not redress their concerns.

In fairness to Taylor, it is important to note that his perspective was influenced by the Protestant ethic, “the value attached to hard work, thrift, and efficiency in one’s worldly calling, which, especially in the Calvinist view, were deemed signs of an individuals’ election, or eternal salvation” (Encyclopaedia Britannica, 2020, para. 1). In the current day, it is difficult to understand Taylor’s view on work as ‘Godly’ and that his desire to ensure employees worked to their fullest capacity was linked to everyone receiving a righteous reward in Heaven. Indeed, timing worker outputs in today’s world, with greater awareness of the risks of repetitive work under pressure, seems inappropriate but Taylor saw it as a noble pursuit:

The principle objective of management should be to secure the maximum prosperity for the employer, coupled with the maximum prosperity for the employe [sic]…throughout the industrial world, a large part of the organisations for employers, as well as for employes [sic], is for war rather than peace, and that perhaps the majority on either side do not believe it is possible so to arrange their mutual relations so that their interests become identical. (Taylor, 1911, p. 9–10)

Essentially, maximum prosperity was associated with maximum efficiency, and this was a Godly pursuit that Unitarists (unitarism) such as Taylor believed, this should not be interfered with by unions (Boddwyn 1961). Taylor’s work culminated in 1911 with the publication of his book The Principles of Scientific Management (Taylor, 1911).

Given he was credible, with experience designing machinery and in industrial supervisory roles, “Taylor’s imagery evoked an enthusiastic response from engineers and factory managers and from a larger group whose interested extended to virtually every institution” (Nelson, 1992, p. 6). He certainly appears to have influenced Henry Ford (b. 1863, d. 1947), of the Ford Motor Company, as Ford used time and motion studies to reduce the complexity of making a car into many steps that could take advantage of the efficiency of the division of labour (Hounshell, 1988). Subsequently, in 1913, Ford became known for revolutionising manufacturing by innovating assembly line production – with work being brought to the worker rather than the worker going to the object being built. The assembly line, together with the overall division of labour, significantly reduced the cost of the cars Ford was producing and made these a widely available consumer item (Ford Motor Company, 2020). However, Nyland asserts that an important point of different between Taylor and Ford exists; Ford actively de-skilled workers as a wage reducing mechanism, whereas Taylor sought worker efficiency (Nyland, 1998).

As its implementation evolved, Scientific Management and Fordism (as Henry Ford’s manufacturing system came to be known) was not without its critics because of the expectations it placed on workers. The fast and repetitive nature of work at the Ford Motor Company initially led to high worker turnover because “workers found the assembly line work boring as they were now doing only one or two task(s)…workers did not like the strict timing that the moving assembly line required” (Ford Motor Company, 2020, para. 3). To address this, Ford increased his wages to double the average wage ($5 an hour) which made the pace more attractive to existing workers and incentivised others to seek work at Ford Motor Company; this provided Ford with a constant source of replacement labour (Ford Motor Company, 2020). This 1914 wage increase was designed to ensure unions could not establish themselves in Ford’s premises and to ensure the cost of human capital would not keep going up indefinitely (Cwiek, 2014). The division of labour, established early in the British Industrial Revolution, enabled Ford to exert considerable control over his workers as anyone could do the unskilled work required on the Ford production line. Box 3.2 contains a video outlining relationship between Taylor’s Scientific Management and Henry Ford’s development of the assembly line.

Box 3.2: Taylor and Ford: Scientific Management and the assembly line.

Source: “Ford and Taylor Scientific Management (Edited)“, Ryngoksu, YouTube

So why this push for productivity? To Taylor it was ‘Godly’, to Marx (see Box 2.3) it was profit driven with employers cashing in on the gap between the cost and value of labour, and, for others, it was simply because of the labour shortage. One ‘solution’ to the labour-shortage issue was to introduce immigration, President Lincoln endorsed this strongly in his third address to Congress in 1863:

I again submit to your consideration the expediency of establishing a system for the encouragement of immigration…there is still a great deficiency of laborers in every field of industry, especially in agriculture and in our mines, as well of iron and coal as of the precious metals. (Lincoln, 1863, para. 18)

He was successful in his lobbying. The Immigration Act of 1864 established a Commissioner of Immigration to facilitate employment-centric immigration (Migration Policy Institute, 2013). The resulting migrants were welcomed until the 1880s when anti-immigrant sentiments began to emerge, one example being the Alien Contract Labor Law of 1885 whereby employers could not contract foreign labour (U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, 2020), however overall immigration from Southern Europe continued in large numbers until World War I (Wittke, 1949). This very briefly contextualises what would come to form the United States’ historical narratives around being built on migrants and, by working hard, these migrants too would be able to achieve economic prosperity offered by the American Dream , “a better, richer, and happier life for all our citizens of every rank” (Adams, 1931, Preface, para. 2).

Mexican Labour in the United StatesMexicans have a long labour history in the United States, however, this is not discussed here. If you are interested to find out more about Mexican workers and immigrants, you may be interested in reading my previous publication.Lynnaire Sheridan (2009), “I Know Its Dangerous” Why Mexicans risk their lives to cross the border, University of Arizona Press. |

|

However, the reality for these migrants was harsh working conditions with few safety provisions. The New York Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire in 1911 impacted mainly recent Italian and Jewish migrant women with 123 women/girls and 23 men dying when exits were blocked in order to prevent workers taking unauthorised breaks (Trasciatti, 2022). Public pressure led to the establishment of a State of New York Factory Investigating Commission which heard reports from field agents, and directly from a variety of related stakeholders, including workers about conditions in manufacturing (Golding, 1989). Resulting from this investigation, in 1913 a federal Department of Labor was established “to foster, promote and develop the welfare of working people, to improve their working conditions and to enhance their opportunities for profitable employment” (MacLaury, 1988, para. 2, citing the legislation). Finally, Sylvis’ aspirations for a Department of Labor that would truly represent the voice of the worker directly to the President were realised (Lombardi, 1942).

Box 3.3: “Can’t Take No More”, excerpt from the 1979 film produced by the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA).

This video provides a good overall summary of the interwoven origins of labour rights, unions and workplace health and safety in the United States, as resulting from their industrialisation.

Source: “Workplace Health and Safety History, to the 1920s“, markdcaitlin, YouTube

The industrialisation of the United States saw craftsmen displaced by low-skilled workers, but the unique conditions, including a labour shortage, resulted in quite different outcomes than in Britain. From its beginnings, the United States had a culture of worker collectives (such as the Lowell Mill girls), which tended to adopt economic coercion methods to achieving labour rights (such as strikes) more than the political approaches seen in Britain with the establishment of the Fabian Society and, subsequently, the British Labour Party. A number of factors, including the tight labour market, then led to employers seeking the maximum productivity from the few workers they had; this became the impetus for Taylorism. Scientific Management then emerged as America’s response to ‘managing’ the rapid change that industrialisation brought and making the best ‘use’ of the interaction between workers and machines.

Past Influencing the present

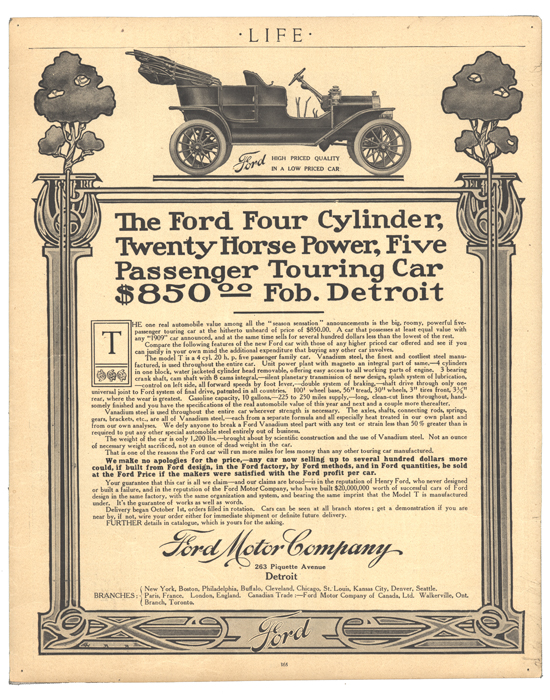

The cost savings achieved by replacing craftsmen with unskilled labourers benefited those producing the goods, but also the consumers. The Industrial Revolution sowed the seed for a growing middle class who could aspire to own products they had never previously imagined possible. Henry Ford, for example, reduced his cost of labour and increased his efficiencies through adopting a moving assembly line to make cars that were affordable to middle class Americans (see Figure 3.4).

Figure 3.4: Ford Model T advertisement from LIFE magazine, October 1908, “ High priced quality in a low priced car“

Source: The Henry Ford on Flickr, CC BY-SA 2.0

Importantly, the challenges Britain and the United States faced in the 18th, 19th and early 20th centuries have, in recent times, simply been transferred to the developing economies today. While we continue to benefit from access to imported cheap consumer goods, in the places where these items are manufactured there is still child labour, long hours, low wages and threats to everyday health (Min et al., 2019). So, while we live the legacies of the Industrial Revolution in our daily lives through school bells in our educational system, others are still more immediately impacted on a daily basis by realities of industrialisation in their countries today. A photograph of a Pakistani child removing dust from a cotton production machine (see Figure 3.5), is uncannily similar to images by Lewis Hines of children working in the American cotton mills in 1916 (see Figure 3.6).

Figure 3.5: A Pakistani child worker, photograph taken January 2016Source: “Cotton and textile industry, Tirupur,” © International Labour Organization, used with permission |

Figure 3.6: American Linen Co. spinning room cleaner, photograph taken June 1916Source: “American Linen Co. Cleaner – Spinning room. Location: Fall River, Massachusetts” by Lewis Hine, Library of Congress, Public Domain |

This section of the book, History: Exploring the origins of labour rights and worker safety, was designed to highlight the historical origins of modern day perspectives on Work Health and Safety by seeing how the development of the concept of ‘labour’ has evolved into domains: labour (employment) relations, the union movement and workplace health and safety. Worker entitlements, worker safety and the right to collective representation of workers to employers, exist in contemporary NZ and Australian legislation as longer-term consequences of the British and American industrial revolutions. It is a period in history that fundamentally shaped our current perspective. Having now established key links between the past and the present, the following section will specifically focus on workplace health and safety from the perspective of HR managers.

“Organization, supervision, or direction; the application of skill or care in the manipulation, use, treatment, or control (of a thing or person), or in the conduct of something” Oxford English Dictionary, n.d., para. 1).

Scientific Management may be defined as: “An approach to management, based on the theories of F.W. Taylor, dealing with the motivation to work. It sees it as a manager’s duty to find out the best way to do a given job, by a process of work measurement, then give each worker individual instructions which have to be strictly followed. The individual is thus seen as the extension of his or her machine, and his or her rewards are also to be allocated mechanically, with more pay expected to produce more output regardless of any other factors” (Statt, 1999, p. 150).

“Of, relating to, or of the nature of paternalism; practising paternalism” (Oxford English Dictionary, n.d., para. 1).

"The value attached to hard work, thrift, and efficiency in one’s worldly calling, which, especially in the Calvinist view, were deemed signs of an individuals’ election, or eternal salvation" (Britannica, 2020, para. 1).

Boston Associates is a term coined by Vera Shlakman to refer to "a small group of investors from Boston were critical to the larger industrial development of New England. This group, connected by social and blood ties, consolidated wealth and dominated the American textile industry during the first half of the nineteenth century" (Charles River Museum of Industry & Innovation, n.d., para. 1).

“Men like Patrick Tracy Jackson, Francis Cabot Lowell and Nathan Appleton were linked together not only because they had made it to the top of Boston’s elite, but because they wanted to make sure that industrial growth did not run amok—that it was restrained by traditional values of community, hard work, social obligation, and decency.” (Charles River Museum of Industry & Innovation, n.d., para. 1).

“Trade union, also called labour union [particularly in the United States], association of workers in a particular trade, industry or company created for the purposes of securing improvements in pay, benefits, working conditions or social and political status through collective bargaining” (Encyclopedia Britannica, n.d., para. 1). Notably, Trade unions emerged in the United Kingdom during the Industrial Revolution to protect craftsperson's rights (they emerged from original crafts guilds), whereas in the United States they drew all workers (skilled and unskilled) together to negotiate labour rights (hence these are known as Labour Unions).

"Is a perspective on employment that emphasizes the shared interests of all members of an organization. It assumes there are compatible goals, a common purpose, and a single (unitary) interest which means that, if managed effectively, the organization will function harmoniously. This viewpoint assumes that conflict is abnormal and is caused by troublemakers, bad communication, and poor management. Consequently, a unitarist will seek to eliminate conflict" (Heery & Noon, 2017).

"Is the extent to which jobs in an organization are subdivided into separate tasks" (Heery & Noon, n.d., para. 1).

"Fordism is a term widely used to describe (1) the system of mass production that was pioneered in the early 20th century by the Ford Motor Company" (Jessop, 2020, para. 1).

“At the corporate level, productivity is a measure of the efficiency of a company's production process, it is calculated by measuring the number of units produced relative to employee labor hours or by measuring a company's net sales relative to employee labor hours” (Kenton, 2023, para. 3).

Is an aspiration for citizens and those who have immigrated to the United States that they can achieve the "American Dream of a better, richer, and happier life for all our citizens of every rank" (Adams, 1931, Preface, para. 2).