6 A systems and safety culture approach to work health and safety management

In Chapter 4, we learned that some organisations will adopt a blame-the-victim approach and will place little importance on WHS management. In Chapter 5, we came to understand that it is only through blaming the system that organisations can move beyond examining human error (active failures) to uncover the latent conditions that, according to James Reason’s Swiss Cheese Model of safety incident causation, increase the risk of a hazard causing harm to workers via a WHS incident.

James Reason’s model then explained why WHS incidents occur but, most importantly, indicated that through addressing latent conditions, incidents can be prevented. However, achieving this concept in practice is complex as notionally each safety defence layer must be unpacked to identify hazards, interventions must be implemented to reduce the risk, and then ongoing monitoring is required to ensure that existing weaknesses (holes in the Swiss cheese) do not recur or new ones do not emerge before they can be rectified.

The goal of this chapter is to give you the systems-based approaches that enable the best possible safety outcome, within the limits of what is reasonably practicable. We will then explore how a safety culture can both embed the safety management system within the organisation, and help avoid, as much as possible, the active human errors associated with poor safety attitudes and behaviours at work.

Learning Objectives

This chapter introduces:

- Systems-based standards for workplace health and safety management.

- The components of a WHS system framework and what each is designed to achieve.

- Safety culture theory.

A system-based approach to WHS

While there are many ways to implement WHS management, we adopt a systems-based approach aligned with James Reason’s Swiss Cheese Model. As WHS management is complex, and WHS incidents expose organisations to business risk, many businesses choose to adopt a standardised framework to assist them in establishing their organisation-specific WHS management system. There are many standardised frameworks used by businesses and they cover different aspects of their operations (environmental management, quality, WHS etc.). These are known as standards.

Box 6.1: What are standards?

In the following video, the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) explains what a standard is and their approach to producing international standards.

Source: “What ISO standards do for you” by the International Organization for Standardization, Vimeo

Standards are agreed to principles and approaches established by panels of experts (International Organization for Standardization, 2023; European Agency for Safety and Health and Work, n.d.). The organisations that establish the standards can then accredit experts to independently audit businesses against these standards and, in turn, businesses that demonstrate compliance with the standards can be certified (United Kingdom Accreditation Service, n.d.). This independent certification can be valuable to businesses who need to demonstrate their effort towards good practice to their stakeholders, such as organisations up or down-stream in their supply chains, because, as Jenks explains, “companies that are able to, at a glance, display brand and strategic value, are more appealing to collaborate with” (2017, para. 20). Certification is also useful as “standards often align with regulatory requirements, and certification can help…demonstrate compliance and avoid potential legal or financial penalties” (Best Practice Certification, 2023, para. 5). At a minimum, adopting standards encourages a coordinated approach to addressing WHS issues and generate the documentation that legal authorities may draw upon in audits or investigations to determine if due diligence requirements have been met.

There are different standards bodies operating in different regions of the world. For example there is the ISO, with it’s origins in establishing uniform adoption of the Metric System (International Organization for Standardization, 1997), but there is also the European Union’s standards that underpin trade agreements (European Agency for Safety and Health and Work, n.d.). The standards framework a business chooses to adopt may be based on common practice in their industry, what is required to supply the product to a market (i.e. meeting European Union standards) or the cost and/or the practicability of implementation and certification.

In Australia and New Zealand, many businesses will be familiar with WHS management standard is AS/NZS ISO 45001:2018 (Occupational health and safety management systems – Requirements with guidance for use) and its predecessor AS/NZS 4801:2001. Endorsed by regional standards bodies, Standards Australia and Standards New Zealand, this particular standard is identical to the international-level ISO 45001:2018 standard (Standards Australia & Standards New Zealand, 2018, p. ii). This means that Australian and New Zealand businesses that achieve AS/NZS ISO 45001:2018 certification, have met international expectations as set by the experts via the ISO.

No matter the WHS standards framework, a safety management system should be designed to “continuously improve safety performance through the identification of hazards, the collection and analysis of safety data and safety information, and the continuous assessment of safety risks” (Civil Aviation Authority of New Zealand, 2023, p. 12). Standardised systems help develop a common language that enable a shared understanding of WHS within the business, and across industries (International Organization for Standardization, 2021). Through fostering collaboration, WHS standards seek to reduce workplace illness, injury and the associated financial, and social costs, of workplace incidents.

Components to a safety management system

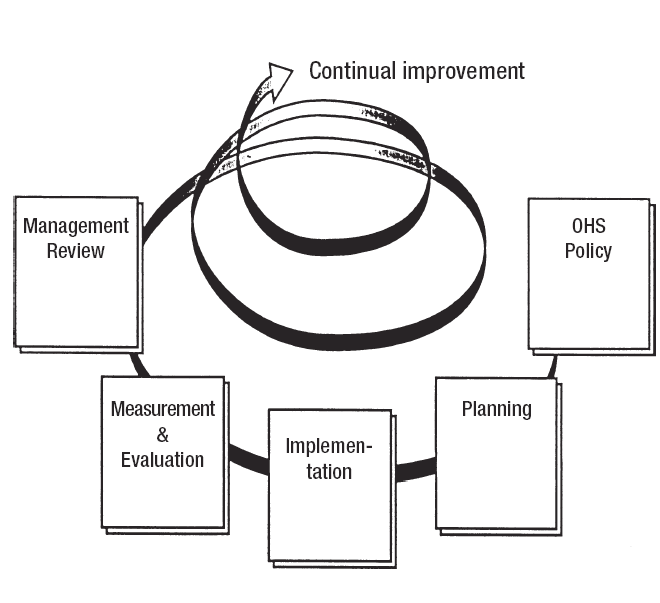

At its core, AS/NZS ISO 45001:2018 provides guidance to organisations on how to set up a safety management system, how to ‘build in’ continual improvement mechanisms and, finally, it helps businesses identify the resources they will need to achieve effective safety management (Standards Australia, 2018). However, in trying to understand current approaches to WHS management systems, it is useful to step back to the prior AS/NZS 4801:2001 to understand what worked and what developments had to take place to establish AS/NZS ISO 45001:2018 as current ‘best practice’. AS/NZS 4801:2001 helped organisations break down the complexity of a safety management system by approaching it in five steps:

- Commitment and policy

- Planning

- Implementation

- Measurement and evaluation

- Review and improvement

Rather than being linear, as presented in the list above, it was proposed as a series of repeatable phases (see Figure 6.1) that organisations would continue to undertake over and over again, with the outcome being continuously improved safety outcomes for their business.

Figure 6.1: AS/NZS 4801:2001, WHS Management System Model

Source: AS/NZS 4801:2001

What does each step comprise? Standards Australia & Standards New Zealand (2001) explain simply that safety management starts at the top. Commitment and policy: Senior leadership teams must commit to safety management and support it’s undertaking through policy and resourcing. Planning: A safety management system’s processes, procedures and measures (key performance indicators (KPIs), lead and lag indicators etc.) must be designed in consultation with key stakeholders before they can be enacted. Implementation: The operationalisation of the planned activities encompassed in the safety management system. Measurement and evaluation: This phase requires reporting from the safety management system on safety outcomes, as measured by the KPIs. Review and improvement: Senior leadership must be informed of the actual safety outcomes, positives and negatives, to determine what improvements must be made to safety management to enhance safety outcomes by the end of the following safety management cycle.

The conundrum for AS/NZS 4801:2001 was that it was heavily focused on the latent, specifically system-based, factors outlined in James Reason’s Swiss Cheese Model (see Figure 5.1). Many businesses became so focused on the administration of the safety management system (the administrative and procedural safety defence layers) that they became “remote from the processes they manipulate and, in many cases, from the hazards that potentially endanger their operations” (Reason, 1998, p. 296). In essence, safety management systems were becoming very bureaucratic and burdensome for the employees, this discouraged reporting of near miss incidents which inevitably diminished the quality of the decision making data (Hudson, 2007). The very high risk-low probability critical incidents that safety management systems were designed to avoid, were still occurring despite safety management system documentation making it appear like the organisation was effectively blocking the holes in their Swiss Cheese Model (Reason, 1998).

This likely occurred because, even today, WHS is a rapidly developing field with practice informing theory, often before theory can inform practice. To address this conundrum scholars, including James Reason, sought to understand the critical role of worker attitudes, beliefs and behaviours (safety culture) in safety management (Hudson, 2007). While active human errors are known to be associated with poor safety attitudes and behaviours at work, these researchers additionally identified that latent conditions were not resolving unless the organisation had a positive safety culture that genuinely sought to enact change.

Components of a safety culture

Reason conceptualises a safety culture as comprising “a reporting culture, a just culture, a flexible culture and a learning culture” (Reason, 1997b, p. 196). By focusing on the development of these individual subcomponents, he believed that a safety culture would emerge via a process of “collective learning…ways of doing, thinking and managing that have enhanced safety health as their natural byproduct” (Reason, 1997b, p. 192).

A reporting culture, where employees report incidents (including near misses), is important to attaining the necessary data to determine which safety defence layers in the Swiss Cheese Model (see Figure 5.1) need actions taken to reduce the probability of a repeat incident. However, organisations notoriously make reporting hazards and incidents difficult, with time-consuming paperwork and processes. Businesses can also be punitive with negative consequences for anyone who reports an incident that was, in part, due to their error. In contrast, organisations that have a functioning reporting culture make reporting easy, provide confidentiality to those who report, and separate business functions that undertake disciplinary processes in the organisations, from those that action WHS continuous improvement. Essentially a reporting culture is based on trust (Reason, 1997b).

A just culture requires workers to “share the belief that justice will usually be dispensed” (Reason, 1997b, p. 205). As outlined by Hopkins & Palser (1987), in a systems-based approach, blaming the victim is rejected. Reason argues instead that a just culture will be lenient towards unforeseen human error, yet provide consequences for “reckless, negligent or even malevolent behaviour of particular individuals” (Reason, 1997b, p. 205).

A flexible culture means the organisation is “able to shift from centralized control to a decentralized mode in which the guidance of local operations depends largely upon the professionalism of first-line supervisors” (Reason, 1997b, p. 218). Reason argues that high quality day-to-day leadership (including usually hierarchical leadership) will often enable a quick and effective transition to those who have the expertise when having to “perform complex and exacting tasks under considerable time pressure” (Reason, 1997b, p. 214). This would, of course, include scenarios such as emergency responses (see Chapter 12).

Finally, a learning culture is where WHS observations, reflections and actions take place. Reason argues that while embedding learning can be easy, achieving actions based on authentic learning derived from observations and reflections is difficult in practice (Reason, 1997b). Theoretically, it is this component of the safety culture that would underpin the continuous improvement aspired to in safety management systems (such as step 5 “Review and Improvement” in AS/NZS 4801:2001).

While Reason’s Safety Culture theory was useful, as it outlined the behaviours of businesses with an effective safety culture, it did not provide organisations with guidance on how to achieve this ideal safety culture. For example, Agim & Sheridan (2013) investigated the subcomponents of Reason’s safety culture in practice and found that just culture is an enabler of a reporting culture. This alone demonstrates that this safety culture theory is useful, but has not yet been fully conceptualised as a working model.

Other scholars therefore examined the characteristics of culture specific to high reliability organisations—those organisations that had implicitly dangerous work but very few incidents. Weick & Sutcliffe identified that these organisations are ‘mindful’ and their safety culture can be understood as a “preoccupation with failure, reluctance to simplify interpretations, sensitivity to operations, commitment to resilience and deference to expertise” (Weick & Sutcliffe, 2001, p. 30). This is a very useful insight but difficult to operationalise without examples from practice, and guidelines on the steps that must be taken to achieve it.

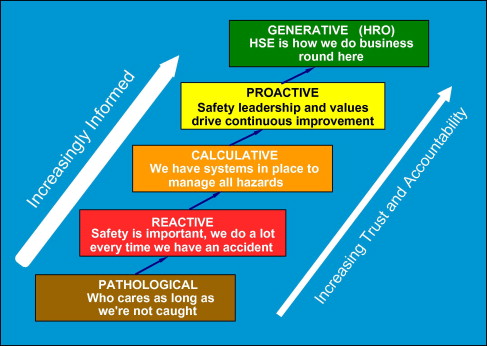

Patrick Hudson progressed this field by proposing a diagnostic tool; a safety culture ladder model (see Figure 6.2) that organisations can use to critically reflect and determine the current status of their safety culture (Hudson, 2007). Ideally, the safety culture would become so embedded that it would be ‘how we do business round here’ but could start from lower levels, such as being reactive, and progress towards becoming ‘generative’.

Figure 6.2: Patrick Hudson’s Safety Culture Ladder

Source: Safe Work Australia on YouTube, CC BY

Box 6.2: Patrick Hudson’s Moving up the culture ladder

The following video provides an in-depth explanation by Patrick Hudson of the conundrums facing safety management systems and his safety culture ladder model.

A transcript of this video is available here.

Source: “Professor Patrick Hudson: Moving up the culture ladder”, Safe Work Australia, CC BY

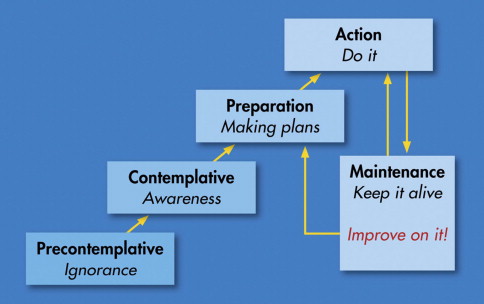

Importantly, Hudson identified that his diagnostic tool (the ladder) needed to be matched with an improvement tool (based on Prochaska and DiClemente’s transtheoretical model, see Figure 6.3) to ensure that, “the culture ladder and the change model, define (i) where an organisation might go and (ii) how it might go there” (Hudson, 2007, p. 705).

Figure 6.3: Patrick Hudson’s Safety Culture Change Model

Source: “The change model based on the transtheoretical model of Prochaska & DiClemente (1983)” by Patrick Hudson, Safety Science

While today it is common to read statements such as:

Organisations with an effective SMS typically show genuine management commitment, creating a working environment where staff are encouraged to engage in and contribute to the organisation’s safety management processes. These organisations benefit from having an active Just Culture policy, supported by regular feedback on what has been done in response to staff reports, and from effective controls to manage the identified risks. Hazard identification, risk assessment, evaluation, and control have therefore become an integral part of day to-day business. Managers and staff understand that supervision of the operations, and therefore safety, is the responsibility of all, not just the Safety Manager. (Civil Aviation Authority of New Zealand, 2023, p. 12)

Acknowledgment of the importance of safety culture, and its integration into a safety management system, is clearly relatively recent.

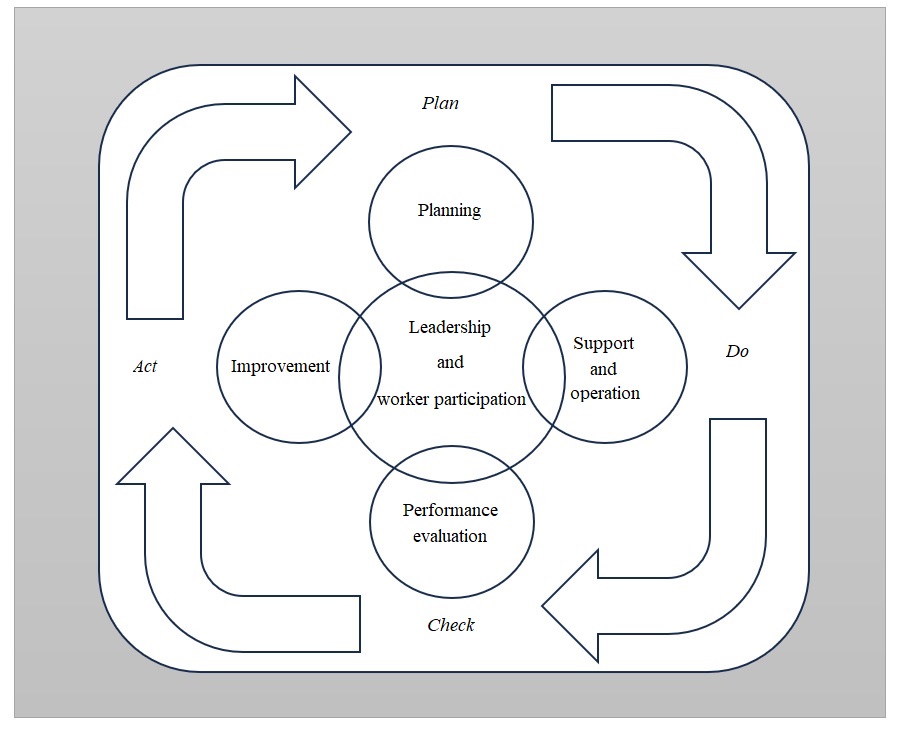

Returning now to consider AS/NZS ISO 45001:2018 (see Figure 6.4), the essence of a safety management system remains similar to that outlined in AS/NZ 4801:2001 but the five phases of a safety management system are now reduced to four (planning, support and operation, performance evaluation and improvement), all enabled through leadership and worker participation which exists within the context of the organisation (external and internal issues as well as the needs and expectations of workers and other interested parties). In the diagram below, the shaded area external to the system’s activities represents these internal and external factors that are constantly acting on the organisation.

Figure 6.4: ISO 45001:2018 conceptualisation of a safety management system

Source: Lynnaire Sheridan, modified from ISO45001:2018, CC BY 4.0

Notably, safety culture is still not explicitly integrated into the Plan-Do-Check-Act (PDCA) cycle of ISO 45001:2018 but it is referred to in its guidance for use:

A culture that supports an organization’s OH&S [WHS] management system is largely determined by top management and is the product of individual and group values, attitudes, managerial practices, perceptions, competencies and patters of activities that determine commitment to, and the style and proficiency of, its OH&S [WHS] management system. (Standards Australia and Standards New Zealand, 2018, p. 27)

ISO 45001:2018 still only focuses on only the reporting culture and just culture sub-components of James Reason’s safety culture theory, as seen in the standards where they state “An important way top management demonstrates leadership is by encouraging workers to report incidents, hazards and risks [reporting culture] and opportunities and by protecting workers against reprisals [just culture], such as the threat of dismissal or disciplinary action, when they do so” (Standards Australia and Standards New Zealand, 2018, p. 27). In the standards, however, we do see elements of Hudson’s (2007) making the plans, do it and improve on it reflected through the integration of PDCA into the diagram (see Figure 6.4). Overall, this suggests that WHS safety management system standards are still only coming to grips with how to embed safety culture into the operationalisation of a safety management system.

At this point, it is important to acknowledge that there is a movement among some scholars to abandon the systems approach to WHS because of the innate challenges of sustaining a data-driven system, while enacting it via a safety culture. One example is Sidney Dekker, who wrote the book The Safety Anarchist: Relying on human expertise and innovation, reducing bureaucracy and compliance (Dekker, 2018). He argues for anarchy, rather than hierarchy. He advocates for horizontal coordination of WHS focused on ‘doing’ rather than reporting. He suggests that the “novelty, diversity and complexity” of WHS incidents are least effectively managed by the bureaucracy that safety management systems create (Dekker, 2018, p. iv). Past influencing the present considers the influence of the Industrial Revolution on contemporary WHS management and the limitations this may present.

Past influencing the present

According to Sidney Dekker, many present-day approaches to WHS (sometimes referred to as Safety I) emerged in response to Industrial Revolution conditions but today constrain our capacity to effectively implement safety management:

For sure, bureaucratic initiatives from the last century—regulation, standardization, centralized control—can take credit for a lot of the progress on safety we’ve made. Interventions by the state, and by individual organizations, have taken us away from the shocking conditions of the early industrial age. We had to organize, to standardize, to come together and push back on unnecessary and unacceptable risk. We had to solve problems collectively; we had to turn to the possibility of coercion by a state or other stakeholders to make it happen…Bureaucracy and compliance may well have taken us as far as they can. (Dekker, 2018, p iv)

If we consider that Scientific Management emerged during the American Industrial Revolution (see Chapter 3), it makes sense that contemporary workplaces—those now heavily influenced by Human Relations School approaches to management—might imagine new ways of organising safety practices that acknowledge the expertise of the worker and seek to harness their intrinsic motivation. Indeed, the opening of Dekker’s film Safety Differently features a worker emphasising the importance of autonomy. If we consider this in the context of the Self-Determination Theory which “proposes that all human beings have three basic psychological needs—the needs for competence, autonomy, and relatedness” (Deci & Ryan, 2015, para. 1), we can see that this modern theoretical lens, derived from the Human Relations School, is influencing contemporary approaches to safety management.

Another worker questions why efforts to enhance safety outcomes focus on failure, rather than success. This perspective aligns with a related contemporary WHS approach known as Safety II. Safety II shifts from blocking the holes in the Swiss cheese, to examining what works in the organisation and replicating that success (Hollnegal et al., 2015).

Box 6.3: Sidney Dekker’s Safety Differently

Source: “Safety Differently | The Movie“, Sidney Dekker, Vimeo

As an important, yet emerging field, WHS research will continue to evolve at a rapid pace. Most businesses either directly, or indirectly, will be engaging in practices derived from James Reason’s Swiss Cheese Model and safety culture theories. Many will be adopting standards-based approaches to developing safety management systems. However, in many ways, Weick & Sutcliffe’s (2001) observations are correct; being vigilant and taking safety seriously is perhaps the only way to achieve effective safety management. We now know that employees internalising personal and collective responsibility towards safety, is vital to achieving this. While progress has been made on how to achieve a safety culture we’ve learned here that it is very much still under development.

Box 6.4: Video 4, An introduction to work health and safety management

The following video is a useful review and further contextualisation of WHS systems and safety culture.

NOTE: Australian and New Zealand Standard 4801:2001 has now been replaced with AZNZ 45001:2018

A transcript of this video is available here.

Source: Sheridan, L. (producer, narrator). (2019). Video 4: An introduction to work health and safety management.

Preston, A. (audio engineer); Orvad, A., (artist) and Franks, R., (animator), Learning, Teaching and Curriculum. University of Wollongong, Australia. YouTube

Activity 6.1

Take this 10 question quick quiz to review your understanding of key concepts introduced in Chapter 6 and see how your learning is progressing.

This section of the book, Theory: A systems approach to work health and safety management, introduced key WHS concepts, adopted a systems-based theoretical approach to safety management and outlined how organisations can use standards to establish their safety management systems. James Reason’s Swiss Cheese Model of safety incident causation was used to conceptualise the relationships between hazards, risk, and safety defence layers in organisations. Safety culture was identified as pivotal to embeding a safety system within a business, and enacting the change required to resolve latent conditions. The next section unpacks each component of safety management systems to understand their enactment in practice.

"Theories about the causes of industrial accidents can be classified into two broad types: those which emphasize the personal characteristics of the workers themselves and those which locate the causes in the wider social, organisational or technological environment. The former approach is conveniently termed blaming-the-victim and the latter, blaming the-system" (Hopkins & Palser, 1987, p. 26).

"Theories about the causes of industrial accidents can be classified into two broad types: those which emphasize the personal characteristics of the workers themselves and those which locate the causes in the wider social, organisational or technological environment. The former approach is conveniently termed blaming-the-victim and the latter, blaming the-system" (Hopkins & Palser, 1987, p. 26).

"Human beings contribute to the breakdown of such [complex technological] systems in two ways. Most obviously, it is by errors and violations committed at the 'shape end' of the system...Such unsafe acts are likely to have a direct impact on the safety of the system and, because of the immediacy of their adverse effects, these acts are termed active failures" (Reason, 1997, p. 10).

"Fallibility is an inescapable part of the human condition, it is now recognized that people working in complex systems make errors or violate procedures for reasons that generally go beyond the scope of individual psychology. These reasons are latent conditions....poor design, gaps in supervision, undetected manufacturing defects or maintenance failures, unworkable procedures, clumsy automation, shortfalls in training, less than adequate tools and equipment - may be present for many years before they combine with local circumstances and active failures to penetrate the system's many layers of defences" (Reason, 1997, p. 10).

"James Reason proposed the image of "Swiss cheese" to explain the occurrence of system failures...According to this metaphor, in a complex system, hazards are prevented from causing human losses by a series of barriers. Each barrier has unintended weaknesses, or holes – hence the similarity with Swiss cheese. These weaknesses are inconstant – i.e., the holes open and close at random. When by chance all holes are aligned, the hazard reaches the patient and causes harm" (Perneger, 2005, p. 71).

In the WHS context, “An incident is an unplanned event or chain of events that results in losses such as fatalities or injuries, damage to assets, equipment, the environment, business performance or company reputation” (Wolters Kluwer, n.d., para. 1).

"Likelihood and consequence of injury or harm occurring” (Standards Australia & Standards New Zealand, 2001, p. 5).

Australia's Model Work Health and Safety Bill defines reasonably practicable as:

"In this Act, reasonably practicable, in relation to a duty to ensure health and safety, means that which is, or was at a particular time, reasonably able to be done in relation to ensuring health and safety, taking into account and weighing up all relevant matters including:

(a) the likelihood of the hazard or the risk concerned occurring; and

(b) the degree of harm that might result from the hazard or the risk; and

(c) what the person concerned knows, or ought reasonably to know, about:

(i) the hazard or the risk; and

(ii) ways of eliminating or minimising the risk; and

(d) the availability and suitability of ways to eliminate or minimise the risk; and

(e) after assessing the extent of the risk and the available ways of eliminating or minimising the risk, the cost associated with available ways of eliminating or minimising the risk, including whether the cost is grossly disproportionate to the risk" (WorkSafe Australia, 2023, Section 18).

"A group or set of related or associated things perceived or thought of as a unity or complex whole" (Oxford Dictionary, 2023, para. 1).

Business risk may be defined as "the exposure a company or organization has to factors that could lower its profits or lead it to fail” (Kenton, 2022, para. 1).

Standards are agreed to principles and approaches established by panels of experts (International Organization for Standardization, n.d.).

"The care that a reasonable person exercises to avoid harm to other persons or their property" (Merriam-Webster, n.d., para. 1).

The Metric System is:

"The International System of Units (SI), commonly known as the metric system, is the international standard for measurement. The International Treaty of the Meter was signed in Paris on May 20, 1875 by seventeen countries, including the United States. The seven SI base units, which are comprised of

Length - meter (m)

Time - second (s)

Amount of substance - mole (mole)

Electric current - ampere (A)

Temperature - kelvin (K)

Luminous intensity - candela (cd)

Mass - kilogram (kg)" (National Institute of Standards and Technology, 2023, p. 2).

“Key performance indicators (KPIs) are used to measure and monitor whether an organization is on the right track…KPIs play an important role in modern organizations improving performance is key to achieving organizational success” (Madsen and Stenheim, 2022, para. 1).

"These indicators refer to the resources needed for the implementation of an activity or intervention. Policies, human resources, materials, financial resources are examples of input indicators. Example: inputs to conduct a training course may include facilitators, training materials, funds" (World Health Organization, 2014, para. 1)

"Outcome indicators refer more specifically to the objectives of an intervention, that is its ‘results’, its outcome...These indicators, therefore, allow us to know whether the desired outcome has been generated. It may take time before final outcomes can be measured" (World Health Organization, 2014, para. 7).

Near misses are "unplanned incidents that occurred at the workplace that, although not resulting in any injury or disease, had the potential to do so” (Archer et al., 2015, p. 86). When contextualised in the Swiss Cheese Model of incident causation, they can be understood as "an event that could have potentially resulted in…losses, but the chain of events stopped in time to prevent this” (Wolters Kluwer, n.d., para. 1).

A critical incident is “a sudden, unexpected and overwhelming event, that is out of the range of expected experiences” (UNHCR, 2019, para. 1).

“A culture that supports an organization’s OH&S management system is largely determined by top management and is the product of individual and group values, attitudes, managerial practices, perceptions, competencies and patters of activities that determine commitment to, and the style and proficiency of, its OH&S management system” (Standards Australia and Standards New Zealand, 2018), p. 27).

"Intended as a punishment" (Cambridge Dictionary, n.d, para. 1).

"Disability is part of being human. Almost everyone will temporarily or permanently experience disability at some point in their life...Disability results from the interaction between individuals with a health condition, such as cerbral palsy, Down syndrome and depression, with personal and environmental factors including negative attitudes, inaccessible transportation and public buildings, and limited social support" (World Health Organization, n.d., para. 1).

Note: This definition is based on the Social Model of Disability. For more information on this see: Ikutegbe P, Randle M, Sheridan L, et al. (2023) Successful employment outcomes for people with disabilities: A proposed conceptual model. 75(3): 202 - 224.

"An emergency response is an immediate, systematic response to an unexpected or dangerous occurrence. The goal of an emergency response procedure is to mitigate the impact of the event on people, property, and the environment. Emergencies warranting a response range from hazardous material spills resulting from a transportation accident to a natural disaster" (Mishra, 2018, para. 1).

High reliability organisations are distinguished from other organisations as they have a: “…preoccupation with failure, reluctance to simplify interpretations, sensitivity to operations, commitment to resilience and deference to expertise” (Weick & Sutcliffe, 2001, p. 30).

“Industrial Revolution, in modern history, the process of change from an agrarian and handicraft economy to one dominated by industry and machine manufacturing. These technological changes introduced novel wasy of working and living and fundamentally transformed society. The process began in Britain in the 18th century and from there speak to other parts of the world…the United States and western Europe, began undergoing the ‘second’ industrial revoltuions by the late 19th century” (Encyclopaedia Britannica, 2023, para. 1).

Safety management is increasingly being classified into two eras (or paradigms); Safety I and Safety II.

Safety I, the dominant safety management paradigm from the 1960s into the 2000s, can be explained as a safety management approach that " presumes that things go wrong because of identifiable failures or malfunctions of specific components: technology, procedures, the human workers and the organisations in which they are embedded. Humans—acting alone or collectively—are therefore viewed predominantly as a liability or hazard, principally because they are the most variable of these components" (Hollnegal et al., 2015, p. 3). The Swiss Cheese Model of incident causation is an artifact of Safety I conceptualisations of safety management.

Safety II has emerged across the 2000s with Hollgegal advocating for a shift "from ensuring that ‘as few things as possible go wrong’ to ensuring that ‘as many things as possible go right’" (Hollnegal et al., 2015, p. 3). Their 2015 white paper "From Safety-I to Safety-II" essential coined the two terms and explained Safety II as assuming "that everyday performance variability provides the adaptations that are needed to respond to varying conditions, and hence is the reason why things go right. Humans are consequently seen as a resource necessary for system flexibility and resilience" (Hollnegal et al., 2015, p. 3).

In summary, Hollnegal et. al. consider Safety I’s focus to be on people as a source of error (active failures), whereas Safety II sees people as a “resource necessary for system flexibility and resilience” (Hollnegal et al., 2015, p. 4).

The Human Relations School of thought was founded by Elton Mayo at Harvard Business School in the early 20th century (O'Connor, 1999). The Human Relations School of thought is a "human relations approach, aimed at improving morale and reducing resistance to formal authority" (Miles, 1965, para. 1).