11 Implementing: Hazard Control

This final hazard and risk chapter focuses on hazard control, determining “appropriate ways to eliminate the hazard, or control the risk when the hazard cannot be eliminated” (Canadian Centre for Occupational Health and Safety, 2023, para. 6). Here the Hierarchy of Control conceptual model is presented to control hazards corresponding to the engineering, procedural and administrative safety defence layers in our Swiss Cheese Model (see Figure 8.1) before examining psychosocial hazards, and other human-related issues, and their management within the people safety defence layer.

Learning Objectives

This chapter introduces:

- The Hierarchy of Control as a useful conceptual model to control chemical, ergonomic, biological and physical hazards.

- Challenges and controls for Human Factors, incorporating performance influencing and psychosocial factors.

- A reflection on the meaning of reasonably practicable, having identified hazards, their risks and potential controls.

Hierarchy of Control

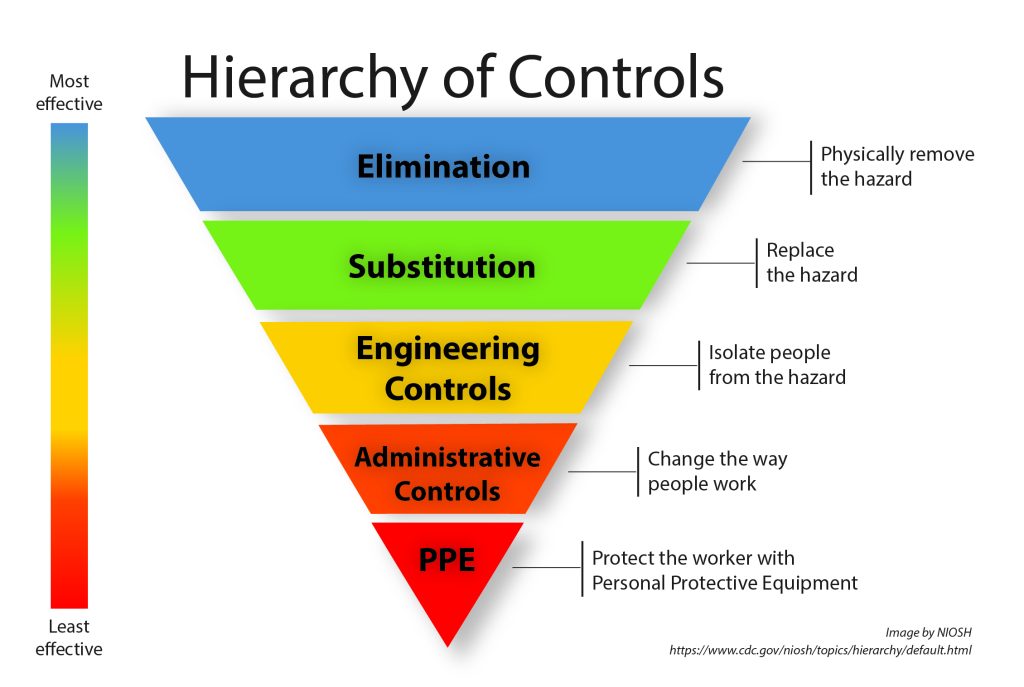

The most important thing to understand when adopting the Hierarchy of Control is that is should always be undertaken in a sequential order from top to bottom (see Figure 11.1). First try to eliminate the hazard: Does the hazard even need to be present in your workplace? If the hazard is vital to undertaking work, could it be substituted with a less dangerous equivalent? If the hazard remains (or even a substitute is brought in), what guarding or other engineering solutions can isolate the workers from the hazard? What administrative controls, such as training, can ensure that the worker only engages with the hazard when needed and that they follow the safest possible work procedures when doing so? Finally, what personal protective equipment can be used as a final protective measure?

Figure 11.1: Hierarchy of Controls

Source: “Hierarchy of controls” by National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, Public Domain

Using this hierarchy is important because WHS managers have the greatest control over the upper tiers of the Hierarchy of Control and the least over the bottom levels. For example, safety management staff can decide to substitute one hazard for another, but it is more difficult to ensure that an individual worker is using their safety glasses all the time. The emphasis put on planning in Chapter 7 is partly because it is tempting to get straight into trying to control hazards without doing things step by step, however, organisations risk spending lots of money on PPE for hazards that do not even need to be in their workplace.

Elimination

Inadvertently, sometimes due to inattentional blindness, hazards are present in our workplace that do not even need to be there. For example, during hazard identification, it may be found that there is an old unused piece of machinery sitting in the corner of the factory floor. While it may appear harmless, it is unnecessary, and its oily residues may present a fire hazard. Do you need to have that ticking timebomb in your workplace or could you have it properly disposed of?

Sometimes the hazard might be ergonomic. Via a workplace risk assessment by an ergonomist, the positioning of equipment might be shifted to eliminate the ergonomic risk. In some cases, these types of hazards will not be able to be resolved this way, and will require administrative controls, but if you can eliminate the hazard upstream in the control process, this is best approach.

Substitution

A chemical may be used to clean metal prior to powder-coating. The chemical currently used may be highly toxic and poses a substantial risk to workers. Could this chemical be substituted by another which is equally effective but less toxic? It is usually not reasonably practicable to continue to use a highly toxic chemical if a good substitute is available. Should the price of the substitute be substantially more, risking the financial viability of the task, it may be reasonably acceptable to remain with the current practice, however, some businesses may decide to eliminate the hazard and outsource that work to a specialist business with specialist hazard controls in place.

Engineering controls

Does your machinery have appropriate guarding to protect your workers from harm? When importing new equipment, it is important that thorough risk assessments are undertaken to ensure that all potential ways that a worker could be injured by the machine and its operation are considered. Ideally then, effective engineering controls can be put in place to inhibit worker contact with hazards, such as moving parts (see Figure 11.2).

Figure 11.2: Moving parts of a machine are guarded by a yellow safety fence

Source: “Sheehan filter press safety guards right hand side” by CDE Global, Flickr.com, CC BY 2.0

When importing machinery, a similar risk assessment should be undertaken and, in many jurisdictions, it is illegal to import machinery without safety guards being attached before supply (Safe Work Australia, 2014); as, unfortunately, some manufacturers sell safety guarding separately which discourages their purchase.

Does your equipment have a clearly marked and accessible emergency ‘stop’ mechanism (button)? In an emergency, it is important that machinery can safely, and quickly, be switched off to reduce further risk of harm (see Chapter 9, Working Alone Example 1). Can your machinery automatically stop? See Past influencing the present for details on a dead man’s switch, an automatic shutoff should an operator lose consciousness.

Past influencing the present

It is taken for granted that a power tool, such as a hand drill, only works while you hold the button down on its handle but this is an engineering hazard control known as a ‘dead man’s switch’ invented in the 1890s.

Figure 11.3: The ‘trigger’ on the hand drill is a small-scale dead man’s switch

Source: “A man holds a cordless drill in his hand on a white background” by Marco Verch, Flickr.com, CC BY 2.0

Frank Sprague was an electrical engineer specialising in trams and railways. One of his inventions, in direct response to fatalities caused by railway disasters, was the dead man’s switch (Sprague, 1932). This switch requires the driver to actively, and continually, be in contact with the device (see Figure 11.4) and when they are not, often due to a medical episode, it will bring the train to an automatic halt as the driver has ceased active control over the train (Newman, 2010).

Figure 11.4: A worker must have their foot pressing the ‘dead man’s switch’ for the control panel to operate

Source: “Dead man’s switch” by Washington State Department of Transportation, flickr.com, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

Note: Engineering controls attempt to address some latent conditions in the Swiss Cheese Model (see Chapter 5) and are notionally considered the engineering safety defence layer in Figure 8.1.

Administrative controls

The purpose of administrative controls is to reduce worker exposure to hazards via appropriate work practices which can include “work process training, job rotation, ensuring adequate rest breaks, limiting access to hazardous areas or machinery [or] adjusting [production] line speeds” (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2023, para. 9). One such control is a Safe Operating Procedure and another is a Safe Work Method Statement (see Box 11.1).

A Safe Operating Procedure (or Standard Operating Procedure) are guidelines on the most efficient, safest, way to undertake the work. By standardising approaches to tasks, “workers don’t have to guess what to do next and can perform tasks efficiently and without danger to themselves or others. Failure to follow SOPs may cause significant safety breaches or loss in production and operational efficiency” (Safety Culture, n.d., para. 1). Again, worker involvement is important to ensure that uptake of Safe Operating Procedure occurs, rather than workers feeling patronised by instruction on simple activities or unrealistic procedures being expected of workers (see Dekker, 2018, and Box 6.3).

Box 11.1: Regulated Safe Work Method Statement for High Risk Construction Work

In addition to a situation requiring a business to undertake risk assessment and control, WHS regulators have specific requirements for high risk hazards and/or work. The Safe Work Method Statement for High Risk Construction Work, is an example of a support resource created by Safe Work Australia to help PCBUs comply with “18 high risk construction work activities defined in the WHS Regulations” (Safe Work Australia, 2020, p. 1). Its purpose is:

To be used if identified as an ‘administrative control’ following a Risk Assessment and is a document that outlines the ‘high risk construction work’ activities to be carried out at a workplace, the hazards that may arise from these activities, and the measures to put in place to control the risks. (University of New England, n.d., para. 8)

A transcript of this video is available here.

Source: Sheridan, L. (producer, narrator) and Treadwell, L. (producer). (2019). Excerpt from Video 6: An introduction to work health and safety management.

Preston, A., (audio engineer); Orvad, A., (artist) and Franks, R., (animator), Learning, Teaching and Curriculum, University of Wollongong, Australia. YouTube

Note: Administrative controls attempt to address some latent conditions in the Swiss Cheese Model (see Chapter 5) and are notionally considered the procedural and/or administrative safety defence layers in Figure 8.1.

Personal Protective Equipment (PPE)

When no other control measures are possible to implement, it is important to ensure that workers are wearing protective equipment that is suitable for their job’s tasks.

Box 11.2: WHS Personal Protective Equipment

A transcript of this video is available here.

Source: Sheridan, L. (producer, narrator) and Treadwell, L. (producer). (2019). Excerpt from Video 6: An introduction to work health and safety management.

Preston, A., (audio engineer); Orvad, A., (artist) and Franks, R., (animator), Learning, Teaching and Curriculum. University of Wollongong, Australia. YouTube

Managers have the least control over PPE implementation and compliance. It is useful, therefore, to come up with engaging ways to create a safety culture that makes wearing, and remembering to wear, PPE part of ‘how things are done around here’. In Box 11.3 Dominion, an American electrical services company, involve their workers in producing a video that, through a very catchy rap song, helps staff remember in the field safety steps and PPE use.

Box 11.3: Safety Rap

In this video, staff have produced a rap song to remind themselves of PPE use and good safety practices in the field. It reinforces the organisation’s safety culture by making safety a social norm.

Source: “Safety Rap” by Dennis McDade, Dominion VA Power, YouTube

It is now important to demonstrate use of the hierarchical qualities of this hazard control tool. Example 1 applies the Hierarchy of Control to a lathe machine and Example 2 applies the Hierarchy of Control to a ladder.

Hierarchy of Control Example 1: A lathe machine at a metal fabricating business

Figure 11.5: An industrial lathe machine

Source: “Workshop lathe machine” by Sunny Bansodeva, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0

Lathes (see Figure 11.5) are tools designed to shape metal or wood (All Metals Fabricating, 2020). In this example, we will assume that the lathe is being used in a metal tool fabrication workshop. While there are many potential hazards, such as heavily lifting, contact with liquid coolant etc., as identified by WorkSafe (2017), this example will only focus on the machine when in operation.

Table 11.1: A Hierarchy of Control analysis of hazard control for a lathe in a metal tool fabrication workshop

| Control | Decision |

| Elimination | Not applicable:

Lathe required for metal tool fabrication. |

| Substitution | Not applicable:

There is no better equivalent on the market. |

| Engineering Controls | Applicable:

Conduct review for automatic stop mechanism, retrofit if required. Conduct review of existing guarding, ensure it is fit for purpose or retrofit if required. Position lathe controls outside of the work zone to reduce potential contact of the lathe with worker limbs. |

| Administrative controls | Applicable:

Ensure that a collaboratively designed safe work procedure has been written. Ensure that operators have had training and that the workplace culture supports adherence to the safe work procedure. |

| Personal Protective Equipment | Applicable:

As objects can get stuck in lathes (loose clothing, jewellery etc.) provide well-fitting clothing and remove loose items. As objects can fall from the lathe, provide appropriate work footwear. As the lathe is loud, provide appropriate hearing protection. |

Source: Lynnaire Sheridan

Note: This table is for illustrative purposes only. It must not be used in place of actual hazard control for a lathe.

Hierarchy of Control Example 2: A ladder used by professional painters for exterior façade painting

Figure 11.6: A worker painting the exterior of a building

Source: “Painter at work above Claire’s Hair Studio, Omagh” by Kenneth Allen, Geograph, CC BY-SA 2.0

Ladders (see Figure 11.6) are a piece of equipment, with steps or rungs, allowing people to access heights above the ground. In this example, we will assume that the ladder is being used by professional painters who paint building facades for a commercial painting business.

Table 11. 2: A Hierarchy of Control analysis of hazard control for a ladder used by commercial painters

| Control | Decision |

| Elimination | Not applicable:

To paint building exteriors, painters need to reach all parts of the building, and this includes working at heights. |

| Substitution | Applicable:

Scaffolding or scissor lifts (see Figure 11.7) are likely safer options for painters working at height due to their greater stability compared to a ladder. It would be ideal if all buildings had their own scaffolding, but this is not the case. Currently the business cannot afford to own and install scaffolding for all the buildings they are concurrently required to paint. They also cannot afford the time to put up and take down a lesser amount of scaffolding. Decision: A scissor lift is hired, as a trial to see if it is suitable for the workers, as it potentially could quickly position—and re-position—the painter to the correct high as required. |

| Engineering Controls | Applicable:

Conduct a risk assessment of the hired scissor lift machine, including testing to see that all safety mechanisms are functioning. |

| Administrative controls | Applicable:

Ensure that either a qualified scissor lift operator is hired along with the machine or ensure that staff undergo correct training to be qualified to operate the scissor lift safely. |

| Personal Protective Equipment | Applicable:

Ensure appropriate personal protective equipment as specified by the company hiring the scissor lifts and/or follow recommendations from the WHS regulator. For example, ensure that workers have apparatus that adheres them to the scissor lift basket. |

Source: Lynnaire Sheridan

Note: This is not an exhaustive hazard assessment and must not be relied upon as an actual hazard control for adoption of a scissor lift for working at heights.

Figure 11.7: Two scissor lifts with safety baskets

Source: “Two slab scissor lifts used by the Tate Modern to install artworks” by Marie-Lan Nguyen, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 2.5

In this example, the original hazard is able to be substituted, however, scissor lifts will have associated hazards and risks that will then also need to be considered.

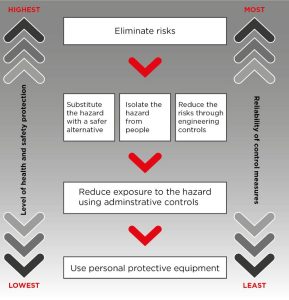

By way of some final comments on the Hierarchy of Control, its depiction in Figure 11.1 is not the only conceptual model available. Safe Work Australia (2023), for example, ranks substitution, isolation and engineering controls as equally comparable in their hierarchy which may be a more useful approach in some business settings (See Figure 11.8).

Figure 11.8: Alternate conceptual model for the Hierarchy of Control

Source: “The hierarchy of control measures” by Safe Work Australia (2023d), CC BY 4.0

Finally, but notably, the Hierarchy of Control is not effective for controlling all types of hazards. Box 11.4 contains a short video outlining when using a hierarchical approach is useful but also when it is not. Given the examples outlined above, it is likely that you can see it appears effective for chemical, ergonomic, biological, physical, safety, and workplace hazards. Hazard controls for human factors, including psychosocial hazards, will now be discussed.

Box 11.4: WHS Hierarchy of Control

The following video provides a useful summary of the concepts discussed in this chapter associated with hazard control.

A transcript of this video is available here.

Source: Sheridan, L. (producer, narrator) and Treadwell, L. (producer). (2019). Excerpt from Video 6: An introduction to work health and safety management.

Preston, A., (audio engineer); Orvad, A., (artist) and Franks, R., (animator), Learning, Teaching and Curriculum. University of Wollongong, Australia. YouTube

Controlling Human Factors

Taking a blame-the-system approach does not preclude us from attempting to control human factors. In the Swiss Cheese Model, the active failure in an incident is usually comprised by human factors (Reason, 1997). What is important is to focus on preventing the conditions that contribute to human error, not on any individual person, because “everyone can make errors no matter how well trained and motivated they are. However in the workplace, the consequences of such human failure can be severe” (Health and Safety Executive, n.d.-b, para. 1).

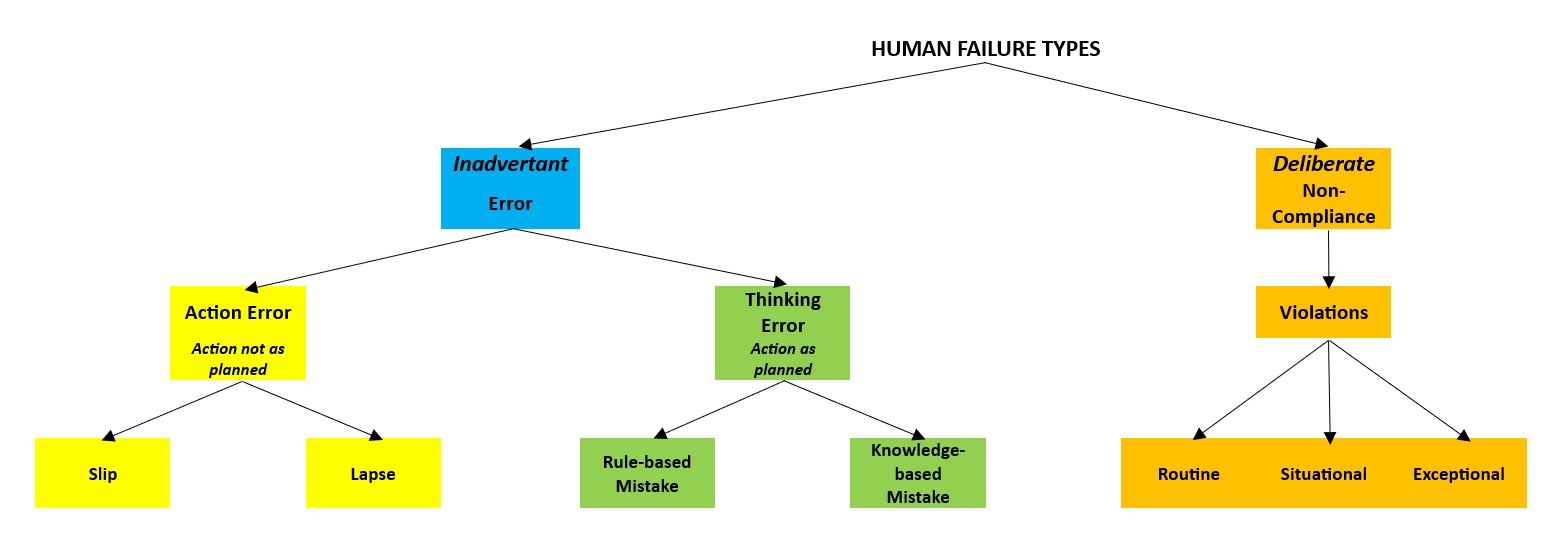

Human failure, however, is not one thing so different types of failures can be classified according to if they are deliberate or inadvertent (see Figure 11.9). The complexity of human factors is the reason why James Reason puts such a focus on the latent conditions in the Swiss Cheese Model because ‘controlling’ individual behaviour, even within a good safety culture, is the most difficult type of hazard control to achieve in a safety management system (Reason, 1997). In essence, both Performance Influencing Factors and psychosocial hazards need to be managed.

Controlling for Performance Influencing Factors

Conditions acting upon workers are considered to be Performance Influencing Factors, “the characteristics of the job, the individual, and the organisation that influence human performance. Optimising PIFs will reduce the likelihood of all types of human failure” (Health and Safety Executive, n.d.-c, para. 1). Figure 11.8 depicts a logic tree for human failures derived from Performance Influencing Factors. Essentially some human failures will be inadvertent whereas others will be deliberate. Health and Safety Executive (n.d.-b) explain that inadvertent errors may result in a slip (a usual action going wrong) or a lapse (a required action not being performed). Deliberate non-compliance violations require investigation to determine if non-compliance is routine (usual), situational (specific to the context on that day, such as time pressures) or exceptional (rule breaking to solve an unexpected problem).

Figure 11.9: Human Failure Types

Source: Lynnaire Sheridan, modified from Health and Safety Executive (n.d.-b, para. 1).

Performance Influencing Factors, and their controls, are perhaps best understood via examples. The first example will explore worker fatigue (likely an inadvertent error) and the second discusses the influence of drugs or alcohol on work (likely deliberate non-compliance).

Performance Influencing Factor Example 1: Fatigue

Fatigue may be defined as “weariness or exhaustion from labor, exertion, or stress” (Merriam-Webster, n.d.-a, para. 1). It is identified as having an impact on “physical, mental, cognitive, emotional, and motivational functionality” (Billones et al., 2021, p. 8). It is a hazard because “the negative effects of fatigue range from losses or productivity at work due to medical disability, occupational hazards, deaths from medication errors, and suicidal ideation (Billones et al., 2021, p. 1).

Figure 11.10: Workplace fatigue increases the risk of human error

Source: “A Woman Resting Her Head on Her Desk” by RDNE Stock Project, pexels.com, Pexels free licence

To identify fatigue requires a risk assessment of staff and considering what is currently known about the causes of fatigue. For example, there is research that clearly links shift work with fatigue (Shen et al., 2006) and shift workers are likely to be an easily identifiable cohort in your worker population. In contrast, fatigue derived from outside of the workplace may be more difficult to identify (see Figure 11.11).

Figure 11.11: There may be many factors contributing to the fatigue experienced by a worker

Source: “Kids making noise and disturbing mom working at home” by Ketut Subiyanto, pexels.com, Pexels free licence

Currently, the most common ways to identify worker fatigue (in New Zealand) is via employee surveys and training managers to identify it in workers (Business NZ, 2021). Where there is a good reporting culture, supported by a just culture that will not blame the worker, these tools might be useful to identify work or home related fatigue. Increasingly however, organisations are seeking to address it as part of a broader wellbeing programme alongside of flexible work arrangements, employee assistance programmes (such as counselling) and even health food initiatives (Business NZ, 2021).

Fortunately, WorkSafe explain:

PCBUs don’t have the sole responsibility to manage fatigue at work. Workers must take reasonable care of their own health and safety…Workers should: turn up in a state fit to work…inform your manager or supervisor if a task is beyond your capabilities…recognise the signs and symptoms of fatigue…communicate with your manager and report fatigue-related incidents. (WorkSafe, 2017, para. 31)

Performance influencing factor assessment:

Fatigue is likely to be an inadvertent error, potentially leading to either action error, a slip or lapse, or a thinking error, a rules-based mistake or knowledge-based mistake (see Figure 11.9).

Performance Influencing Factor Example 2: Drugs and/or alcohol

Worker drug and alcohol consumption can impact on workplaces as it causes absenteeism (reduced work attendance) and presenteeism (reduced work performance when attending at work). Presenteeism costs businesses up to four times more than absenteeism because it generates impacts such as “reduced productivity and quality of work, job errors, injury, the negative effect on co-workers, inefficient use of resources and damaged property amongst others” (Sullivan et al., 2019, p. 543).

Figure 11.11: A drug test kit

Source: “Multi-drug Screen Test and Kit Boxes” by Curtis Adams, pexels.com, Pexels free licence

While drug and alcohol testing to determine if employees are fit to work might appear the best solution, as a medical procedure it requires careful (including legal consideration). Notably in the New Zealand context, “generally an employer may only ask employees and other workers to agree to alcohol or drugs tests if this is a condition of their appointment and in the employment agreement or workplace policies” (Ministry of Business, Employment and Innovation, n.d-d). The Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment refer employers to the International Labour Organization’s Code of Practice on the management of alcohol and drug-related issues in the workplace (see ILO, 1996) for further guidance.

Performance influencing factor assessment:

Drugs or alcohol being present in a worker’s system is likely to be deliberate non-compliance which is either a routine, situational or exceptional violation of workplace policy (see Figure 11.9).

Controlling psychosocial hazards

In contrast to human failures, caused by Performance Influencing Factors on an individual, psychosocial hazards tend to be generated by conditions in the workplace (recall examples such as lack of role clarity or poor organisational justice or bullying from Figure 9.7). WorkSafe suggest that “effective psychosocial risk management is dependent on the key agents having adequate knowledge, relevant and reliable evidence and effective and user friendly methods and tools, and the availability of competent experts, services and institutions, and research and development” (WorkSafe, 2019, p. 60). Clearly PCBUs must empower competent staff to enact psychological controls within their organisations.

A challenge posed by psychosocial hazards is that many of them can go unnoticed. Safe Work Australia (2022) explains that physical violence is obvious, others are less distinguishable in a generally poor workplace culture. Psychosocial injury flourishes when certain workplace demographics combine with low workplace diversity in a poor workplace culture. This reinforces statements by Reason (1998), Hudson (2007) and Dekker (2018) that a strong safety culture be considered pivotal to WHS management. It also supports calls from the HR profession for workplace diversity across gender, age, ethnicity etc. (Ely & Thomas, 2020).

Effectively controlling psychosocial hazards requires organisations to address internal conditions (perhaps through changing recruitment practices to incorporate diversity into the workplace) at the same time as putting specific measures into place including ensuring safe access to their facilities (protecting staff from uninvited perpetrators), making all parts of the workplace visible (ensuring there are no areas where a worker could be trapped by another person), and controlling workplace temperatures (literally keeping things cool to keep people calm). Along side of these can be procedural interventions (extricating violent clients), through to administrative strategies, including training to build awareness of psychosocial hazards among staff (Safe Work Australia, 2022).

Note: Psychosocial hazard controls attempt to address some active failures in the Swiss Cheese Model (see Chapter 5) and are notionally considered the people safety defence layer in Figure 8.1.

Box 11.5: Video 5, An introduction to work health and safety management

A transcript of this video is available here.

Source: Sheridan, L. (producer, narrator) and Treadwell, L. (producer). (2019). Video 5: An introduction to work health and safety management.

Preston, A., (audio engineer); Orvad, A., (artist) and Franks, R., (animator), Learning, Teaching and Curriculum, University of Wollongong, Australia. YouTube

Determining what is reasonably practicable

Once you have identified your hazards, undertaken risk assessment and devised hazard controls, it is time to determine what is reasonably practicable to implement. While an initial safety management budget may have been established, what is reasonably practicable is not simply costing-out what can be afforded this financial year. Instead, to ensure due diligence, determining what is reasonably practicable will require collaborative discussions between safety staff, workers, representatives of workers (unions), sometimes WHS regulators and, very importantly, the senior leadership of the organisation.

Aligning stakeholder risk perceptions is important because, no matter the rigour of likelihood and consequences tools, the resource limitations of organisation will always demand a moral, values-based, judgement of what hazard controls are to be actioned, versus those activities that will be left until the next safety system cycle or even set aside indefinitely. Given the critical relationship between leadership commitment towards safety and safety resource allocation, it is important to identify that hazard control is constrained by financial resources. Less committed organisations will control fewer hazards and expose their workers to greater risk of harm. However, workers should be able to have a reasonable expectation to safely return home from work each day.

Box 11.6: What is reasonably practicable?

Through a process of aligning stakeholder risk perceptions, decisions can be made that prioritise hazard control according to the likelihood and severity of an incident within the organisation’s logistical and budgetary constraints. The organisation then progresses its safety management based on what is reasonably practicable at that point in time. This is the focus of the following video.

A transcript of this video is available here.

Source: Sheridan, L. (producer, narrator) and Treadwell, L. (producer). (2019). Excerpt from Video 6: An introduction to work health and safety management.

Preston, A., (audio engineer); Orvad, A., (artist) and Franks, R., (animator), Learning, Teaching and Curriculum. University of Wollongong, Australia. YouTube

Activity 11.1

Take this ten question quick quiz to review your understanding of hazard identification, risk assessment and hazard control concepts as introduced across Chapters 9, 10 and 11, and see how your learning is progressing.

In concluding this discussion of hazard controls, it is important to point out that implementing controls for all identified hazards will take time. Workers will continue to be exposed to an unacceptable risk levels until the organisation is able to implement hazard controls. This is why the next chapter is focused on how to achieve an effective emergency response, and how to escape a hazard, if necessary, to minimise harm.

"Standard Operating Procedure (SOP) sometimes called a Safe Operating Procedure, outlines a set of detailed instructions to help workers perform complex tasks properly and safety. Having standard operating procedures in place means workers don't have to guess what to do next and can perform tasks efficiently and without danger to themselves or others. Failure to follow SOPs may cause significant safety breaches or loss in production and operational efficiency" (Safety Culture, n.d., para. 1).

"Inattentional blindness is a popular human error associated with selective attention or inattention. It can be depicted as an individual’s failing to notice or recognize a visual object or event due to a lack of active attention in a given situation" (Park et al., 2022, p. 1),

"The design of furniture or equipment and the way this affects people's ability to work effectively" (Cambridge Dictionary, n.d., para. 1).

"Someone who studies the design of furniture or equipment and the way this affects people's ability to work effectively" (Cambridge Dictionary, 2023, para. 1).

Australia's Model Work Health and Safety Bill defines reasonably practicable as:

"In this Act, reasonably practicable, in relation to a duty to ensure health and safety, means that which is, or was at a particular time, reasonably able to be done in relation to ensuring health and safety, taking into account and weighing up all relevant matters including:

(a) the likelihood of the hazard or the risk concerned occurring; and

(b) the degree of harm that might result from the hazard or the risk; and

(c) what the person concerned knows, or ought reasonably to know, about:

(i) the hazard or the risk; and

(ii) ways of eliminating or minimising the risk; and

(d) the availability and suitability of ways to eliminate or minimise the risk; and

(e) after assessing the extent of the risk and the available ways of eliminating or minimising the risk, the cost associated with available ways of eliminating or minimising the risk, including whether the cost is grossly disproportionate to the risk" (WorkSafe Australia, 2023, Section 18).

"James Reason proposed the image of "Swiss cheese" to explain the occurrence of system failures...According to this metaphor, in a complex system, hazards are prevented from causing human losses by a series of barriers. Each barrier has unintended weaknesses, or holes – hence the similarity with Swiss cheese. These weaknesses are inconstant – i.e., the holes open and close at random. When by chance all holes are aligned, the hazard reaches the patient and causes harm" (Perneger, 2005, p. 71).

In principle, and in accordance with the Australian Model Work Health and Safety Bill, a regulator is a legally established government body whose functions are:

“ (a) to advise and make recommendations to the Minister and report on the operation and effectiveness of this Act;

(b) to monitor and enforce compliance with this Act;

(c) to provide advice and information on work health and safety to duty holders under this Act and to the community;

(d) to collect, analyse and publish statistics relating to work health and safety;

(e) to foster a co-operative, consultative relationship between duty holders and the persons to whom they owe duties and their representatives in relation to work health and safety matters;

(f) to promote and support education and training on matters relating to work health and safety;

(g) to engage in, promote and co-ordinate the sharing of information to achieve the object of this Act, including the sharing of information with a corresponding regulator;

(h) to conduct and defend proceedings under this Act before a court or tribunal;

(i) any other function conferred on the regulator by this Act”

(Safe Work Australia, 2023, section 152).

A PCBU, a person conducting a business or undertaking, “may be an individual person or an organisation. This does not include workers or officers of PCBUs, volunteer associations, or home occupiers that employ or engage a tradesperson to carry out residential work” (WorkSafe, 2019, p. 4).

"Theories about the causes of industrial accidents can be classified into two broad types: those which emphasize the personal characteristics of the workers themselves and those which locate the causes in the wider social, organisational or technological environment. The former approach is conveniently termed blaming-the-victim and the latter, blaming the-system" (Hopkins & Palser, 1987, p. 26).

"Human factors refer to environmental, organisational and job factors, and human and individual characteristics, which influence behaviour at work in a way which can affect health and safety" (Health and Safety Executive, n.d.-b, para. 1).

In the WHS context, “An incident is an unplanned event or chain of events that results in losses such as fatalities or injuries, damage to assets, equipment, the environment, business performance or company reputation” (Wolters Kluwer, n.d., para. 1).

“A culture that supports an organization’s OH&S management system is largely determined by top management and is the product of individual and group values, attitudes, managerial practices, perceptions, competencies and patters of activities that determine commitment to, and the style and proficiency of, its OH&S management system” (Standards Australia and Standards New Zealand, 2018), p. 27).

"Performance Influencing Factors (PIFs) are the characteristics of the job, the individual and the organisation that influence human performance. Optimising PIFs will reduce the likelihood of all types of human failure (Health and Safety Executive, n.d.-c, para. 1).

"An employee assistance program (EAP) is a work-based intervention program designed to assist employees in resolving personal problems that may be adversely affecting the employee's performance...Programs are delivered at no cost to employees by stand-alone [independent] EAP vendors or providers" (SHRM, 2023, para. 1).

"Fit to work or fitness to work is a medical assessment done when an employer wishes to be sure an employee can safely do a specific job or task" (Canadian Centre for Occupational Health and Safety, n.d., para. 1).

"The care that a reasonable person exercises to avoid harm to other persons or their property" (Merriam-Webster, n.d., para. 1).