7 Establishing: Leadership commitment, policies, procedures and planning

Organisations that blame-the-victim will not prioritise safety management (see Chapter 4); they only consider the active failures (human error) within their businesses and will not genuinely adopt systems-based approaches to address latent conditions. As James Reason would explain it through his safety culture theory, a learning culture will not exist within these businesses; as Patrick Hudson would explain it, they are likely pathological or, at best, reactive (see Figure 6.2). In contrast, this chapter takes the perspective of a business that has adopted a blame-the-system philosophy and is now seeking to establish a safety management system.

Learning Objectives

As outlined in ISO 45001:2018, this chapter introduces:

- Leadership commitment as an enabler of safety management.

- The role of policy and procedures in establishing safety management in an organisation.

- The vital importance of planning before establishing a safety management system.

Leadership Commitment

In ISO 45001:2018, leader commitment to safety is fundamental to achieving safety management system success because it ensures the resourcing required to enact the system and establish the safety culture (Standards Australia & Standards New Zealand, 2018). However, even when taking a blame-the-victim approach, organisational levels of commitment to safety do vary. As a WHS professional, it is vitally important to determine the extent to which your organisation’s leadership team values, and is committed to, safety otherwise you may face “tensions and burdens due to…general management not embracing ethical values, and safety being regarded as a value while facing financial and economic constraints” (Lindout & Reniers, 2021, p. 8518). If your leaders are not committed to safety, your ability to enact safety and develop a safety culture, is limited (Hudson, 2007).

So how can you determine an organisation’s level of commitment to safety? Patrick Hudson’s Safety Culture Ladder (see Figure 6.2) is one tool (Hudson, 2007). Discussions with staff are likely to reveal if a blame-the-victim or blame-the-system approach prevails within the business. Reviewing an organisation’s safety record would likely position the organisation on one rung of the ladder (pathological, reactive, calculative, proactive and generative) and would highlight any pathological recidivism (repeat offending).

So how do organisations make decisions regarding their commitment to safety? Again, analysing Hudson’s Safety Culture Ladder it appears that pathological and generative organisations make moral choices, whereas reactive, calculative and proactive organisations adopt a risk-centric, cost-benefit analysis, approach. Examining the moral versus business risk approach is therefore useful.

A moral commitment to safety

Morality may be defined as “’what is right?’ …respect for autonomy, non-maleficence, beneficence and justice” (Lindout & Reniers, 2021, p. 8515). The decision by senior leaders to commit to safety is a moral judgement, the “evaluation of actions with respect to moral norms and values established in society” (Thoma et. al. 1991 cited in Li et al., 2017, p. 122). In making their choice, some senior leaders will take a relativistic stance; they will make their judgement based on the situation or individuals involved. In contrast, those who “value moral principles of harm/care and fairness/reciprocity more highly…are more likely to experience distress toward harm and outrage toward injustice” (Li et al., 2017, p. 135) and would support safety as a moral impetus.

HR managers engaged in safety management likely have little influence over a senior leader’s moral commitment to safety. Depending on your moral stance, the value placed on safety may be an important consideration in selecting your place of work. This said, moral decision-making is not the only driver for the implementation of WHS management, often the impetus is business risk avoidance enabling a business case to be made for safety.

A business-risk derived commitment to safety

Not to be confused with safety-specific risk, business risk may be defined as the “exposure a company or organization has to factors that could lower its profits or lead it to fail” (Kenton, 2022, para. 1). Kenton (2022) suggests that business risk is comprised of four principal risks: strategic, compliance, operational or reputational. Safety management, at least in its early stages within many organisations, is likely prioritised according to the risk poor safety management presents in the each of these four domains. However, WHS management also presents good business opportunities, as effective safety practices should mitigate:

- compliance risk: averting prosecution for negligence.

- operational risk: with continuous safety improvement enhancing productivity through design efficiencies (better ergonomics), better control of maintenance regimes etc.

- reputational risk: averting WHS incidents.

Up until this point, we have viewed WHS management as a people-centric HR business function. This is because the origins of safety management are derived from the Industrial Revolution concurrent with employment relations (labour rights) and unions (see Chapters 1–3). However, the subsequent evolution of WHS management theory (see Chapters 4–6) has led to a systems-based philosophy which, increasingly, aligns WHS with environmental and quality risk management approaches (Kauppila et al., 2015). This risk-centric response recognises that businesses need a social licence to operate, an “ongoing acceptance of a company or industry’s standard business practices and operating procedures by its employees, stakeholders, and the general public” (Kenton, 2023, para. 1). WHS is being drawn into an alternate philosophical frame grounded in sustainability and the triple bottom line, there is now an expectation that business should be reporting on “their social and environmental impact—in addition to their financial performance—rather than solely focusing on generating profit, or the standard ‘bottom line'” (Miller, 2020, para. 5). WHS management, and its performance outcomes, through this lens are then perceived as a social good sustaining an organisation’s social licence to operate, rather than a worker entitlement.

Box 7.1: John Berry, Social licence to operate

In this video John Berry, an expert in sustainable investing, discusses the implications of the concept of a social licence to operate on contemporary business.

Source: Leckie, T. & Sheridan, L. (producers) (2023). Business for Good: John Berry.

Molloy, J. (video and audio), Pearce, J. (coordinator), Hortle, L. (assistant), Media Production Unit, the Otago Business School. University of Otago, New Zealand. YouTube

Sustainability reporting is one approach taken by organisations to foster their social licence to operate. Sustainability reporting requires businesses to provide “an overview of the economic, environmental, social and cultural impacts, caused by an entity’s activities” (External Reporting Board, 2023). Compiling these reports, usually undertaken for compliance and reputational reasons, can be exceedingly complex. One strategy to simplify their operationalisation is to have the key performance indicators (KPIs) aligned and managed across business functions within management systems.

Similar to safety management systems (Chapter 6), there are standards are used to manage the business risks associated with the natural environment (ISO 14001) or product quality (ISO 9001) (International Organization for Standardization, n.d.). Again, these standards are likely to be operationalised via environmental or quality systems before they are audited and certified to independently demonstrate an organisation’s fulfilment of the social licence to operate. One organisation adopting the combined systems approach to safety management is Unilever (see Box 7.2).

Box 7.2: Unilever, a systems-based approach to managing business risk

Figure 7.1: Unilever’s brand logo

Source: Unilever on Flickr.com, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

Unilever is a large multinational organisation operating in more than 190 countries (Unilever, n.d.-a). Given their cross-border operations, they use a standards-based approach to ensure compliance in all jurisdictions where they operate (Unilever, n.d.-b). Ideally, they would be adopting practices from their most demanding legislative jurisdictions and applying these across the entire business.

The sustainability performance data collected by Unilever is categorised into environmental and occupational [work] safety (emissions, waste, water, and occupational safety incidents), planet (climate action, waste, water, and environmental fines), society (safety at work, nutrition, community investment), and people (recruitment, workforce composition, gender diversity, learning and development, and retention). All these KPIs are verified through independent auditing and certification. Management of quality is implied across their business indicators with references to being a good employer (Unilever, .n.d-c) and their focus on producing high quality consumer products (Unilever, n.d.-d).

Further reading:

Unilever (n.d.-b) Sustainability reporting standards. Available at: https://www.unilever.com/planet-and-society/sustainability-reporting-centre/reporting-standards/ (accessed 12/10/2023).

Seeing safety through the business risk lens—rather than solely through the HR lens—explains why safety management is showcased on the international stage via initiatives such as the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals where safety is implicit in Goal 3: Good Health and Well-being and Goal 8: Decent Work and Economic Growth (United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, n.d.). As explained by the Institution of Occupational Safety and Health (UK):

Workplace health and safety is all about sensibly managing risks to protect your workers and your business. Good health and safety management is characterised by strong leadership involving your managers, workers, suppliers, contractors and customers. In a global context, health and safety is also an essential part of the movement towards sustainable development. (2021, para. 1)

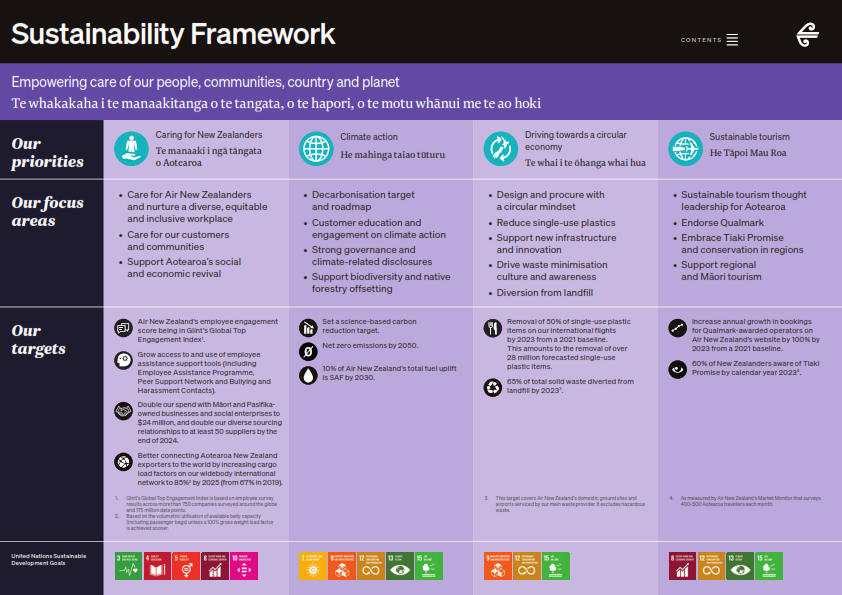

Box 7.3: Air New Zealand, Sustainability Reporting

In its sustainability reporting, Air New Zealand is attempting to communicate all its KPIs in one table that encapsulates environmental, safety and quality risk management at the local level (New Zealanders) through to a global level (UN Sustainable development Goals).

Figure 7.2: Extract, Air New Zealand 2023 Sustainability Report

Source: Air New Zealand (2023, p. 11).

In this holistic sustainability framework, the first column ‘Caring for New Zealanders’ positions caring for workers as the top priority. This care is to be achieved, in part, through organisational and staff alignment with the key values of diversity and equity. There is no specific mention of WHS, but it does infer that Air New Zealand is promoting a just culture which, in turn, can foster a positive safety culture according to James Reason’s Safety Culture theory (Reason, 1998).

The KPI for care towards New Zealanders (employees) is a staff engagement score (output indicator) that is benchmarked against a global measure (Glint’s Global Top Engagement Index with 750+ organisations surveyed) together with input indicators including employee uptake of their Employee Assistance Programme. The latter metric demonstrates proactive mental health support for workers to address issues, including those outside of work, and is then paired with bullying / harassment prevention programmes (likely input indicators, i.e. number of training attendees) to reduce work-based issues. Beyond employees, the organisation’s care extends to customers and New Zealand communities, each with their own respective metrics (see Figure 7.2).

Air New Zealand’s local-level care for New Zealanders is then linked to United Nations Sustainable Development Goals to demonstrate a contribution towards global collective efforts: Goal 3: Good Health and Wellbeing, Goal 4: Quality Education, Goal 5: Gender Equality, Goal 8: Decent Work and Economic Growth plus Goal 10: Reduced Inequalities. These goals are all WHS related directly (Goal 3 and Goal 8), or indirectly (Goal 4, Goal 5, and Goal 10) as they support positive workplace environments.

The second column “Climate Action” reflects Air New Zealand’s environmental performance commitments. The focus is clearly on the de-carbonisation of their business activities together with offsetting them, via forestry inputs, as a form of climate impact mitigation. First, they outline how they will create scientifically developed measures to evaluate any carbon reduction followed by a net zero 2050 target and a 10% uptake of sustainable aviation fuel by 2030. Likewise, the third column is environment-centric “Driving towards a circular economy” and focuses on the potential good that can be achieved through procurement supply chains, from an environmental and social perspective. The final column “Sustainable Tourism” seeks to balance the environmental impacts of tourism, including their impacts in providing air travel, with the socio-economic benefits that tourism can offer. Air New Zealand links these aspirations to United Nations Sustainable Development Goal 7: Affordable and Clean Energy, Goal 9: Industry, Innovation and Infrastructure, Goal 12: Responsible Consumption and Production, Goal 13: Climate Action and Goal 15: Life on Earth. Goal 8: Decent Work and Economic Growth is also mentioned, and is likely associated with Sustainable Tourism’s potential positive socio-economic outcomes.

Overall, the Air New Zealand Sustainability Framework identifies both global and local sustainability priorities. As an organisation that operates across national and regional boundaries, this dual perspective is fundamental to its social license to operate; domestically it will be critiqued for its positive or negative impacts on local communities, and, internationally, its environmental performance will be evaluated relative to other global airlines.

Further reading:

Air New Zealand (2023) 2023 Sustainability Report. Available at: https://p-airnz.com/cms/assets/PDFs/2023-Air-New-Zealand-Sustainability-Report-Final.pdf (accessed 14/10/2023).

While some organisational leaders adopt a relativistic moral stance towards safety and decide “who cares as long as we’re not getting caught” (Hudson, 2007, p. 704; see Figure 6.2), the strategic, compliance, operation and reputational business risks can make a compelling business case for safety management. Surely even those who take a relativistic stance would see the potential benefits that effective safety management might generate (see pro-safety management arguments as presented in Box 7.4).

Box 7.4: Creating a business case for safety

The Institution of Occupational Safety and Health (UK) motivates PCBUs to undertake safety management by explaining that safety is important to their business because:

-

It is morally right to ensure your workers return home safe and healthy at the end of every working day.

-

By protecting your workers, you reduce absences, ensuring that your workplace is more efficient and productive.

-

Research shows that workers are more productive in workplaces that are committed to health and safety.

-

Reducing down-time caused by illness and accidents means less disruption – and saves your business money.

-

In some countries, health and safety legislation is criminal law and you are legally obliged to comply with it. Legal breaches can result in prosecution, fines and even imprisonment of senior executives.

-

To attract investors and partnerships you may need to demonstrate your commitment to sustainability and corporate social responsibility, which will include how you protect your workers.

-

Increasingly, customers want to buy products and services that are produced ethically – so you also need to think about the work practices throughout your supply chain and deal only with ethical suppliers that protect their workforce.

-

More and more, job hunters—particularly Millennials and Generation Z—seek roles with employers who share their values, so without strong corporate responsibility and sustainability practices you may struggle to attract or retain the best employees.

-

A good health and safety record is a source of competitive advantage: it builds trust in your reputation and brand, while poor health and safety performance will directly affect profitability and can result in loss of trade or even closure of the business.

-

Good health and safety at work secures long-term benefits for you, your business and the wider community. (2021, para. 2)

Point 1 adopts a moral stance whereas points 2–10 justify safety management using business risk as the motivator.

However, we should be cautious in judging an organisation as reactive if they adopt a business-risk based approach to safety management, as it be a methodological approach to safety that co-exists with a strong moral commitment to safety. Dubbink & Van Liedekerke (2020) suggest we should not to misconceive an organisation’s sense of duty as purely being relativistic, in this case as solely being compliance driven. Fundamentally, what is important here is that you understand that safety management cannot happen without leadership commitment, but also that you consider your moral stance towards safety because this will define how you enact safety management.

Policies and procedures

Once senior leadership commitment is secured, it is time to establish the policies and procedures that will outline the organisation’s interpretation and boundaries for safety management. These will then establish the behavioural parameters that will underpin the organisation’s safety culture. Policies may be defined as “rules and guidelines that define and limit action, and indicate the relevant procedures to follow” (Heery & Noon, 2017, para. 1); policy takes a top-down approach. In contrast, procedures are “step-by-step sequences of actions that should be taken to attain particular objectives” (Heery & Noon, 2017, para. 1), and should take a bottom-up approach, as they will only be adopted if are actionable in practice.

While safety concepts may be integrated into broad business policy documents, procedures should be very specific to the safety activity, for example outlining the responsibilities and expected actions of staff during an emergency response. Policy should set the tone of the organisation’s expectations around safety, while the procedures are how, in practice, to get it done.

Note: At this stage, the procedures being discussed are focused on how to operationalise the safety system, not to be confused with standard (safe) operating procedures that can only emerge via worker consultation when undertaking hazard control (see Chapter 11).

Planning

Once policy is in place, formally establishing the organisation’s intention to enact safety management, the planning (P in the Plan-Do-Check-Act) stage of the systems-based safety management cycle begins; often this requires recruitment of staff into key safety-specific roles. These organisational safety pioneers must have knowledge and experience in the comprehensive end-to-end planning of safety management systems; to evoke success these practitioners begin with the end in mind—the requirements of management reporting that enables continuous safety improvement—and work backwards identifying what is reasonably practicable to achieve. These staff principally design and manage the system: compliance with the standards, determine the measurable KPIs to adopt, set up internal and external audit cycles to facilitate safety certification, and also continue to engage with senior leadership to ensure the ongoing commitment to safety management and its improvement within their organisation.

Importantly, these safety professionals recognise that it is easy to worry and immediately seek to identify hazards and manage their risks, however, they know that a lack of a coordinated approach quickly turns this into an overwhelming task. Moreover, they understand that taking this approach could damage the emerging safety culture of the business; by not figuring out how to involve staff in determining what is reasonably practicable and communicating this, workers may become disillusioned when their safety expectations are not met.

Planning comprises designing literally every component of the system, from determining who is responsible for which parts of the organisation’s policy and procedures, through to the specific tools and techniques that workers are to adopt to reduce the possibility of active failures (human errors) combining with latent conditions. Planning identifies everything required to reduce worker exposure to occupational health and safety (incident-centric) hazards. While coordinated by systems safety staff, specialist roles may also be established to enable this, such as hiring in occupational health specialists or hazard and risk assessment experts.

Once the plan for how to operationalise the safety management system has been established, the organisation must begin by reviewing the legislative requirements applicable to their jurisdiction; the next chapter focuses on achieving the compliance competency necessary before establishing a safety management system.

"Theories about the causes of industrial accidents can be classified into two broad types: those which emphasize the personal characteristics of the workers themselves and those which locate the causes in the wider social, organisational or technological environment. The former approach is conveniently termed blaming-the-victim and the latter, blaming the-system" (Hopkins & Palser, 1987, p. 26).

"Human beings contribute to the breakdown of such [complex technological] systems in two ways. Most obviously, it is by errors and violations committed at the 'shape end' of the system...Such unsafe acts are likely to have a direct impact on the safety of the system and, because of the immediacy of their adverse effects, these acts are termed active failures" (Reason, 1997, p. 10).

"Fallibility is an inescapable part of the human condition, it is now recognized that people working in complex systems make errors or violate procedures for reasons that generally go beyond the scope of individual psychology. These reasons are latent conditions....poor design, gaps in supervision, undetected manufacturing defects or maintenance failures, unworkable procedures, clumsy automation, shortfalls in training, less than adequate tools and equipment - may be present for many years before they combine with local circumstances and active failures to penetrate the system's many layers of defences" (Reason, 1997, p. 10).

James Reason conceptualises a safety culture as comprising “four critical subcomponents of a safety culture: a reporting culture, a just culture, a flexible culture and a learning culture” (Reason, 1997, p. 196). By focusing on the development of these individual subcomponents, he believes that a safety culture will emerge as “ways of doing, thinking and managing that have enhanced safety health as their natural byproduct” (Reason, 1997, p. 192).

"Theories about the causes of industrial accidents can be classified into two broad types: those which emphasize the personal characteristics of the workers themselves and those which locate the causes in the wider social, organisational or technological environment. The former approach is conveniently termed blaming-the-victim and the latter, blaming the-system" (Hopkins & Palser, 1987, p. 26).

“A culture that supports an organization’s OH&S management system is largely determined by top management and is the product of individual and group values, attitudes, managerial practices, perceptions, competencies and patters of activities that determine commitment to, and the style and proficiency of, its OH&S management system” (Standards Australia and Standards New Zealand, 2018), p. 27).

A business case is "an explanation or set of reasons describing how a business decision will improve a business, product, etc., and how it will affect costs and profits and attract investments" (Cambridge Dictionary, n.d, para. 1).

"Likelihood and consequence of injury or harm occurring” (Standards Australia & Standards New Zealand, 2001, p. 5).

“Strategic risk is when a business does not operate according to its business model or plan” (Kenton, 2022, para. 8).

“Compliance risk primarily arises in industries and sectors that are highly regulated” (Kenton, 2022, para. 9).

Operational risk “arises from within the corporation, especially when the day-to-day operations of a company fail to perform” (Kenton, 2022, para. 10).

Reputational Risk “Any time a company’s reputation is ruined, either by an event that was the result of a previous business risk or by a different occurrence, it runs the risk of losing customers and its brand loyalty suffering” (Kenton, 2022, para. 11).

"The design of furniture or equipment and the way this affects people's ability to work effectively" (Cambridge Dictionary, n.d., para. 1).

“Industrial Revolution, in modern history, the process of change from an agrarian and handicraft economy to one dominated by industry and machine manufacturing. These technological changes introduced novel wasy of working and living and fundamentally transformed society. The process began in Britain in the 18th century and from there speak to other parts of the world…the United States and western Europe, began undergoing the ‘second’ industrial revoltuions by the late 19th century” (Encyclopaedia Britannica, 2023, para. 1).

An employment relationship is "the connection between employees and organizations through which individuals sell their labour to an employer. In practice, employment relationships can be short-term or long-term, can be governed by informal understandings or an explicit contract, and can involve workers and organizations of all types. From a legal perspective, the laws in each country define what is considered an employment relationship covered by employment and labour law as well as other public policies such as unemployment insurance or social security" (Budd, 2016, p. 123).

The nature of employment relationships are "defined by their terms, which spell out the rights, entitlements and obligations of employers and employees" (McAndrew, 2016, p. 92).

Labour "means any valuable service rendered by a human agent in the production of wealth, other than accumulating and providing capital or assuming the risks that are a normal part of business undertakings" (Encyclopedia Britannica, 2022, para. 1).

“Trade union, also called labour union [particularly in the United States], association of workers in a particular trade, industry or company created for the purposes of securing improvements in pay, benefits, working conditions or social and political status through collective bargaining” (Encyclopedia Britannica, n.d., para. 1). Notably, Trade unions emerged in the United Kingdom during the Industrial Revolution to protect craftsperson's rights (they emerged from original crafts guilds), whereas in the United States they drew all workers (skilled and unskilled) together to negotiate labour rights (hence these are known as Labour Unions).

“Environmental risk management is the process of systematically identifying credible environmental hazards, analyzing the likelihood of occurrence and severity of the potential consequences, and managing the resulting level of risk” (Speight, 2015, p. 322).

“Quality risk management is a systematic, risk-based approach to quality management. The process is composed of the assessment, control, communication, and review of quality risks. It is especially critical in the pharmaceutical industry, where product quality can greatly affect consumer health and safety” (Safety Culture, 2023, para. 1).

“Key performance indicators (KPIs) are used to measure and monitor whether an organization is on the right track…KPIs play an important role in modern organizations improving performance is key to achieving organizational success” (Madsen and Stenheim, 2022, para. 1).

"The social license to operate (SLO), or simply social license, refers to the ongoing acceptance of a company or industry's standard business practices and operating procedures by its employees, stakeholders, and the general public. The concept of social license is closely related to the concept of sustainability and the triple bottom line" (Kenton, 2023, para. 1).

Standards are agreed to principles and approaches established by panels of experts (International Organization for Standardization, n.d.).

“A law or set of laws suggested by a government and made official by a parliament” (Cambridge Dictionary, n.d., para. 1).

“The power, right, or authority to interpret and apply the law…the limits or territory within which authority may be exercised” (Merriam-Webster, n.d., para. 1).

"The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, adopted by all United Nations Member States in 2015, provides a shared blueprint for peace and prosperity for people and the planet, now and into the future. At its heart are the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), which are an urgent call for action by all countries - developed and developing - in a global partnership. They recognize that ending poverty and other deprivations must go hand-in-hand with strategies that improve health and education, reduce inequality, and spur economic growth – all while tackling climate change and working to preserve our oceans and forests" (United Nations, 2023, para. 1).

"Outcome indicators refer more specifically to the objectives of an intervention, that is its ‘results’, its outcome...These indicators, therefore, allow us to know whether the desired outcome has been generated. It may take time before final outcomes can be measured" (World Health Organization, 2014, para. 7).

"These indicators refer to the resources needed for the implementation of an activity or intervention. Policies, human resources, materials, financial resources are examples of input indicators. Example: inputs to conduct a training course may include facilitators, training materials, funds" (World Health Organization, 2014, para. 1)

A relativistic stance is "based on the belief that truth and right and wrong can only be judged in relation to other things and that nothing can be true or right in all situations" (Cambridge Dictionary, 2023, para. 1)..

A PCBU, a person conducting a business or undertaking, “may be an individual person or an organisation. This does not include workers or officers of PCBUs, volunteer associations, or home occupiers that employ or engage a tradesperson to carry out residential work” (WorkSafe, 2019, p. 4).

"Used to refer to a situation in which decisions are made by a few people in authoriy, rather than by the people who are affected by the decisions" (Cambridge Dictionary, n.d, para. 1).

"A way of planning or organizing something that considers the smaller parts or details, or the lower or less powerful levels of a group of organization, first" (Cambridge Dictionary, n.d, para. 1).

"An emergency response is an immediate, systematic response to an unexpected or dangerous occurrence. The goal of an emergency response procedure is to mitigate the impact of the event on people, property, and the environment. Emergencies warranting a response range from hazardous material spills resulting from a transportation accident to a natural disaster" (Mishra, 2018, para. 1).

"Standard Operating Procedure (SOP) sometimes called a Safe Operating Procedure, outlines a set of detailed instructions to help workers perform complex tasks properly and safety. Having standard operating procedures in place means workers don't have to guess what to do next and can perform tasks efficiently and without danger to themselves or others. Failure to follow SOPs may cause significant safety breaches or loss in production and operational efficiency" (Safety Culture, n.d., para. 1).

"Good consultation enables workers to respond and contribute to issues that directly affect them, and provide valuable information and insights. It’s a two-way process where information and views are shared between PCBUs and workers. PCBUs can become more aware of hazards and issues experienced by workers, and involve them in finding solutions or addressing problems. Workers often notice issues and practices, or foresee consequences, that might otherwise be overlooked. PCBUs must genuinely consult with workers and their representatives, including HSRs, before any changes or decisions are made that may affect their health and safety. Consultation should take place during both the initial planning and implementation phases so that everyone's experience and expertise can be taken into account" (Safe Work SA, 2023, para. 8).

Hazard control is determining "...appropriate ways to eliminate the hazard, or control the risk when the hazard cannot be eliminated" (Canadian Centre for Occupational Health and Safety, n.d., para. 6).

“The Plan-do-check-act cycle is a four-step model for carrying out change. Just as a circle has no end, the PDCA cycle should be repeated again and again for continuous improvement” (ASQ, 2023, para. 1) where the different steps are: “Plan: Recognize an opportunity and plan a change, Do: Test the change. Carry out a small-scale study; Check: Review the test, analyze the results, and identify what you’ve learned; Act: Take action based on what you learned in the study step” (ASQ, 2023, para. 3).

Australia's Model Work Health and Safety Bill defines reasonably practicable as:

"In this Act, reasonably practicable, in relation to a duty to ensure health and safety, means that which is, or was at a particular time, reasonably able to be done in relation to ensuring health and safety, taking into account and weighing up all relevant matters including:

(a) the likelihood of the hazard or the risk concerned occurring; and

(b) the degree of harm that might result from the hazard or the risk; and

(c) what the person concerned knows, or ought reasonably to know, about:

(i) the hazard or the risk; and

(ii) ways of eliminating or minimising the risk; and

(d) the availability and suitability of ways to eliminate or minimise the risk; and

(e) after assessing the extent of the risk and the available ways of eliminating or minimising the risk, the cost associated with available ways of eliminating or minimising the risk, including whether the cost is grossly disproportionate to the risk" (WorkSafe Australia, 2023, Section 18).

"A safety audit is a process that is considered the gold standard for evaluating the effectiveness of occupational health and safety programs. Their primary purpose is to identify health and safety hazards, assess the effectiveness of the measures in place to control those hazards, and ensure compliance with the Occupational Health and Safety Administration's (OSHA) standards. Safety audits are conducted by independent audit consultants in order to ensure an unbiased review of policies, procedures, and safety management systems" (Safeopedia, 2021, para. 1).

Certification is the auditing of a business, by an independent accredited entity, to demonstrate (certify) its compliance with standards set by a standards organisation (United Kingdom Accreditation Service, n.d.).

Occupational health had its modest beginnings in first aid and disease controls for high risk heavy industry workplaces, such as mines, but gained greater recognition in the 1970s when the World Health Organization acknowledged its contribution to the identification of workplace-derived factors causing occupational illness and suggested its remit should be broadened to encompass public health. So, today, many occupational health specialists have more of a public health, and less of an immediate workplace, focus (Schilling, 1989).

In the WHS context, “An incident is an unplanned event or chain of events that results in losses such as fatalities or injuries, damage to assets, equipment, the environment, business performance or company reputation” (Wolters Kluwer, n.d., para. 1).

A hazard may be defined as "anything with the potential to harm life, health or property" (Dunn, 2012, p. 53).