4 Sustainable Financial Instruments

Jacquelyn Humphrey

Chapter Overview

At the end of this chapter you will be able to:

- Understand the different ways responsible investment portfolios can be formed

- Analyse the difference between “voice” and “exit”

- Apply your existing knowledge about bond instruments to sustainable investments.

Sustainability in Portfolios and Managed Funds

Investors will usually invest in multiple assets i.e. a portfolio. Investors can select their own assets and create their portfolios, but many investors choose to invest via a managed fund, rather than assets directly. As you will recall, a fund (also known as a mutual fund, a managed fund or a unit trust), pools investors’ money and invests in a portfolio of assets. The clip below provides a quick reminder of how funds work.

What is a Fund? (YouTube, 1m 18s):

Sustainable funds are probably the easiest way for individuals to access sustainable financial products, due to the low initial investment requirements. There is a wide range of ways in which sustainable funds can be formed, and the available strategies have also developed over time. In this chapter we look at different strategies that can be used to form sustainable portfolios. Investors could use these strategies themselves, or they can be used by fund managers to form sustainable fund products.

Early Strategies

In the West, the earliest challenges to traditional finance strategies (i.e. just focus on maximising return and minimising risk) were made by groups of Christian investors who did not want their money to be invested in activities that violated their religious values. In particular they did not want to invest in what have come to be known as sin stocks: companies in tobacco, alcohol, gambling, pornography, or weapons manufacture. These investors asked their investment managers to design products for them that excluded stocks in these industries. Thus was born negative screening. Negative screening was also later (through the 1970s to the 1990s) extended to excluding stocks from repressive regimes, specifically South Africa during the apartheid era, and later Sudan. Today some investments will screen out, for example, Russian investments after the invasion of Ukraine.

Negative screening is not as simple as it may first appear. A company may indirectly be involved in an activity, although it is not its primary business. For example, if a negative screen for alcohol were to be applied, this would not only affect companies that directly manufacture or sell alcohol, but also exclude restaurants, hotels and even grocery stores (e.g., Woolworths and Coles sell alcohol in some Australian states). In this case, a revenue threshold is often applied where any company that derives x% of its revenue from alcohol is excluded.

From here, investors started to say that they did not only want to exclude undesirable stocks, but also invest more in (overweight) companies that have a positive influence on society. Positive screening is where a company is included in a portfolio because of its performance in a desirable social or environment area. Example of positive screens are companies that treat their employees well (good labour relations) or invest in clean technology.

Best in class investment also arose, which can be thought of as a type of positive screening. Under this approach, companies with the best ESG (environmental, social and governance) performance, usually relative to other companies in the same industry, are included in the portfolio. For example, a portfolio could include the top 30% highest ESG-rated companies in each industry. The advantage of best in class investment is that whole industries are not excluded from the portfolio or overweighted in the portfolio. In other words, a diversified portfolio can be achieved through this approach.

Current Landscape

Today, investment products that use positive and negative screens are still widely available. However, other approaches to investment have also developed.

As awareness of and concern about climate change has grown, environmental issues have also been included into the list of issues investors wish to be considered. Furthermore, many “mainstream” financial institutions have now started to offer products that consider a wider range of issues than just risk and return. ESG investment has now become somewhat mainstream. Mainstream investors typically see ESG issues as risks, and therefore considering ESG factors in decision-making has to some extent been added to the traditional risk-management strategy. These investors want the best of both worlds – they want both good ESG practices and good returns. This approach is usually referred to as ESG integration.

Sustainability- themed investing is where investments are made with particular ESG themes, such as sustainable property or low carbon investments.

Impact investment has also developed. Similar to ESG investment, impact investments provide capital specifically to address social and/or environmental issues. However, in general, the ESG impact is more important than the financial return for impact investors. However, these investors do still expect some return from these investments – even if it is below a risk-adjusted market rate.

Finally, philanthropy is where money is given to a “good cause” e.g. a charity, the arts, or sports. You are probably aware of individual philanthropists, but corporations can also engage in philanthropy. This can mean corporations give money to a cause, but can also include, for example, employees volunteering their time to the community. Philanthropy done well is not easy – the firm’s philanthropic activities need to be integrated into the firm’s strategy and activities.

Philanthropic giving by companies is often seen as where ESG in corporations began. However, while philanthropy can form part of a company’s ESG strategy, for a company to be seen as an ESG leader, it is not enough to just give some money away. In fact, some argue philanthropy directs money away from implementing effective ESG strategies and can be considered greenwashing if donating money is used to distract attention from the company’s poor ESG practices. Another argument against company philanthropy is that if shareholders wanted to donate money, they could do so themselves privately, and further, it is unlikely that corporations would choose to donate to the same organisations or causes that investors would choose themselves.

Poll

Divestment Versus Engagement: Which Strategy is Better?

What happens when investors are not happy with the ESG performance of companies in which they are invested? There are a number of strategies that can be used. Corporate engagement and shareholder activism are where shareholders engage with these companies and try to push them to do better on ESG issues. Engagement can take many forms, such as writing letters to companies’ management, meeting with management to discuss ESG issues or by bringing resolutions to be voted upon at companies’ annual general meetings. These methods have also been called using “voice”.

If the investors hold shares in the companies directly, they can use voice. Alternatively, if they choose to invest in funds, they can choose funds which commit to exercising voice (in this case, it is the fund that holds the shares in the company directly, not the investor). However, one difficulty is that most shareholders have relatively small holdings in their portfolio companies, and therefore do not have enough voting rights to push for change on their own. This is why collective engagement – which we discussed in Chapter 3 – can be very important if these ESG engagements are to be successful.

Of course, the other option if investors are not happy with a company’s ESG performance is they can simply sell their shares in that company. This is called divestment, or “exit”. The problem with exit, however, is that investors are then no longer owners of the company and have no way to influence the company for the better.

Engagement versus divestment (voice versus exit) is quite a complex balancing act and has been the topic of much recent discussion. Watch the video below to learn more about divestment versus engagement.

Engagement vs Divestment (YouTube, 3m, 47s):

Implementing the Strategies

How do investment managers implement these strategies? Some use third-party data providers which rate companies on ESG criteria. Others have their own in-house ESG investment teams which do their own research. Some use a combination of third-party providers and their own ESG investment team for particular issues.

Example

Australian Ethical (AE) was Australia’s first fund manager to offer funds that incorporated ESG issues. AE offers managed funds (including exchange traded funds) as well as superannuation and retirement products. AE has an in-house team that does the research on ESG issues.AE uses absolute negative screening for some issues e.g., animal testing, human rights abuses, tobacco, coal mining and nuclear weapons. Revenue thresholds are applied for other negative screens such as alcohol and components to make weapons. AE also does not invest in government bonds issued by authoritarian regimes – in 2022 this meant the Russian, Belarussian, Myanmar and Chinese governments. Several positive screens are applied e.g. preservation of endangered ecosystems, poverty alleviation and sustainable land use and food production.

AE also actively engages with the companies in their portfolios through corporate engagement and shareholder activism. For example in 2022, AE voted on 4,755 items, of which 803 were a vote against company management. These “against” votes included voting on a lack of diversity of the companies’ boards, compensation, human rights, climate and employee welfare issues.

AE has a foundation through which it donates 10% of its profits to charities, currently with a strong emphasis on donating to non-profit organisations that combat climate change.

Find out more about Australian Ethical.

A Spectrum of Investments and Investment Returns

As we have seen from the discussion so far, there is substantial variation in what investors want in terms of ESG versus financial returns. The figure below summarises different types of investment approaches. As we move from left (traditional investment) to right (philanthropy), the requirement for competitive financial returns becomes less important and the ESG issues and impact become more important.

Concept Check

Sustainability in Bond Markets

Bonds are debt instruments i.e. provide a way for companies or other organisations to borrow from the financial markets. Unlike shareholders, bondholders are not owners of the companies and therefore do not have voting rights. Bonds are becoming a popular way for organisations to finance sustainable projects. We will look at five different types of bonds in this section: green bonds, social bonds, social impact bonds, sustainability bonds and sustainability-linked bonds.

Green Bonds

Green bonds are bonds whose proceeds must be used to finance projects that specifically address climate issues. The Climate Bonds Initiative estimates that to date there has been USD 2.2 trillion issued in green bonds globally.[1] Most bonds (just under 60%) are issued by corporations. Europe is by far the largest issuer of green bonds, but as you can see from the figure below, the green bond market has been increasing rapidly over the last decade in every part of the globe.

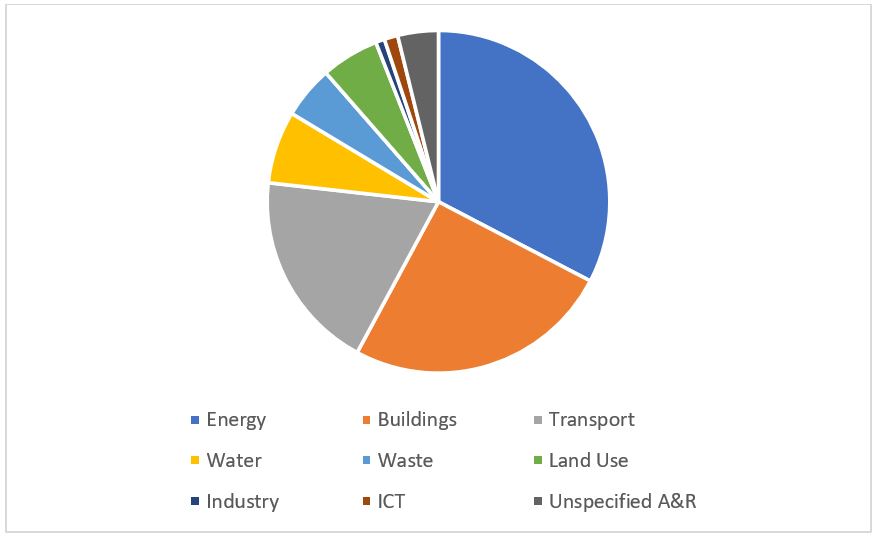

The chart below shows the types of climate issues that green bonds have been used to fund. These figures were from 2022 and show that green bonds have mainly been issued to fund projects relating to energy, buildings and transportation.

Case Study: Apple

Apple has issued multiple green bonds, starting in 2016 with a $1.5 billion issuance, which was the largest green bond by a U.S. corporation at the time. The proceeds are used to finance environmental initiatives, including renewable energy projects, energy efficiency improvements, and sustainable materials sourcing. Apple’s use of green bonds to fund the installation of solar panels and wind farms has significantly contributed to Apple’s goal of having its global facilities powered entirely by renewable energy.

Exercise

Why do you think the green bond market has been rapidly increasing worldwide in recent years?

Answer:

The green bond market has experienced rapid growth globally in recent years due to several key factors.

- First, there is an increasing recognition of the urgent need to address climate change and environmental degradation. This has led to greater demand for sustainable investment options among investors who are keen to support projects that mitigate climate risks and promote environmental sustainability.

- Regulatory frameworks and policies, particularly in Europe, have also been supportive of green bonds, encouraging both issuers and investors to participate in this market.

Corporations like Apple are interested in issuing green bonds for several reasons.

- Firstly, green bonds provide a means to finance their sustainability initiatives, such as renewable energy projects, energy efficiency improvements, and sustainable materials sourcing. By issuing green bonds, corporations can access capital specifically earmarked for these purposes, often at favourable terms due to the high demand for sustainable investments.

- Furthermore, issuing green bonds may also enhance a corporation’s reputation and brand value. Demonstrating a commitment to environmental sustainability can strengthen stakeholder relations, including with customers, investors, and regulators, and can differentiate the company in a competitive market. For Apple, green bonds have facilitated significant investments in solar panels and wind farms, advancing their goal of powering global facilities with renewable energy, thereby reinforcing their sustainability credentials.

- Lastly, green bonds align with broader corporate strategies aimed at managing long-term risks and capitalising on new opportunities in the green economy. As sustainability becomes increasingly integrated into business models, corporations recognise that green bonds can play a crucial role in achieving both financial and environmental objectives.

This convergence of interests drives the growing popularity of green bonds among corporations globally.

Social Bonds

Similar to green bonds, social bonds are used to raise capital to fund specific social issues such as affordable housing, health or unemployment. The social bonds market is significantly smaller than the green bond market, with the Climate Bonds Initiative estimating that there has been a total of USD 653 billion raised by social bonds to date.[2] The issues are also substantially smaller than green bonds – in 2022, the average social bond issue size was USD 55 million compared with USD 140 million for green bonds.

Unlike green bonds which are mainly issued by corporations, most social bonds are issued by governments or development banks. According to the Climate Bonds Initiative, since 2014, 57% of social bonds were issued by government, government-backed entities or development banks.[3]

Social Impact Bonds

Note that there is another type of bonds called Social Impact Bonds (SIBs) or Social Benefit Bonds. These are not the same as social bonds. SIBs are complex financial instruments which are designed to use private sector capital to address social issues that are usually paid for by governments.

In a SIB, the government will engage a service provider to provide a service to the affected population to address a particular social issue. The service provider is paid by money raised via the SIB i.e. from investors buying the SIB. Investors only receive their money back (sometimes with an additional return, but sometimes not) if a particular pre-specified outcome is achieved.

As an example, the first SIB was launched in the UK in March 2010 by the Ministry of Justice and the Big Lottery Fund, and was used to fund a program at Peterborough Prison to reduce reoffending rates. The service provider would work with offenders for up to twelve months after they were released. The program was offered to three groups of prisoners. The terms of the SIB were that investors would receive a return if and only if there was a 10% lower reoffending rate in any of the three groups, or a 7.5% reduction across the three groups receiving the program versus the control group (those that did not participate in the program).

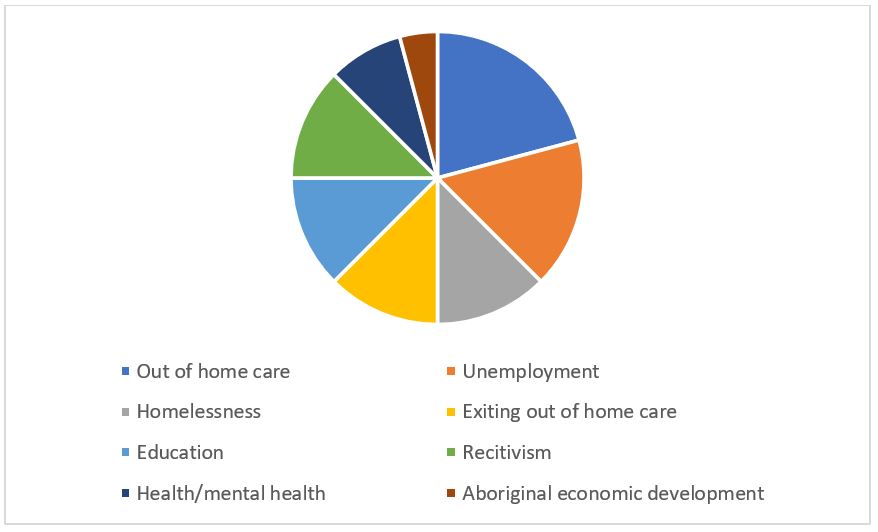

The SIBs market is still small. By October 2022, only 218 SIBs had been launched globally.[4] In Australia, SIBs have tended to be issued by state governments: the NSW, Queensland, South Australia and Victoria governments have all issued at least one SIB. The issues funded by Australian SIBs are shown in the diagram below.[5] In New Zealand, SIBS have been used to address mental health, youth reoffending and social housing.

Sustainability Bonds

Sustainability bonds finance projects which aim to achieve both environmental and social goals. The Climate Bonds Institute estimates that by the end of 2022 there had been 3679 sustainability bonds issued globally.[6] The majority of sustainability bonds have been issued in the USA (2059) followed by South Korea (320), and most are issued by local governments. There have been 20 sustainability bonds issued in Australia and 8 in New Zealand.

Sustainability-linked Bonds

Sustainability-linked bonds are slightly different in that the capital raised is not tied to funding a specific environmental or social project. Instead, the bond is linked to the organisation achieving particular ESG targets. If the targets are not met, the issuer is penalised by having to pay a higher rate (coupon) to investors. Sustainability-linked bonds are a relatively new instrument, with the first issued by an Italian energy company, ENEL in late 2019. The box below provides more information on the first ENEL bond.

The World’s First Sustainability-linked Bond

Issuer: Enel Finance International NV

Launch date: 10 September 2019

Maturity: 10 October 2024

Issue amount: USD 1.5 billion

Target: by 31 December 2021, 55% of ENEL Group’s total consolidated installed energy capacity was to be from renewable generation (as of 30 June 2019, this was 45.9% i.e. they needed to increase renewable capacity by just over 9%)

Penalty: If the target was not achieve, coupons would increase by 25 basis points for the remainder of the bond’s life

Bond Certification

A major concern in sustainable investment is whether the investment is actually delivering the ESG outcomes that it promises. One way for bond issuers to signal that the funds will genuinely be used for the purported purpose is to have them independently certified by a third party. Research shows that investors view sustainable bonds that have been certified by independent third parties more favourably than bonds that do not have such certification.[7]

Two leading global certification agencies are the Climate Bond Initiative and the International Capital Market Association. The European Green Bond Standards and ASEAN Green Bond Standards have also been developed for their respective markets. These organisations also provide frameworks for companies to be able to demonstrate that their bonds meet the requirements for certification.[8]

Review Questions

Complete the chapter review questions below to test your knowledge.

- Climate Bonds Initiative. (2022). Sustainable debt global state of the market 2022. https://www.climatebonds.net/files/reports/cbi_sotm_2022_03e.pdf ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Brookings. (2022). Global Impact Bonds database snapshot October 1, 2022. https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/Impact-Bonds-Snapshot_October-2022.pdf ↵

- Social Ventures Australia. (2022, December 9). A guide to outcomes contracting and social impact bonds. https://www.socialventures.com.au/sva-quarterly/a-guide-to-outcomes-contracting-and-social-impact-bonds/ ↵

- Climate Bonds Initiative. (2022). Use of proceeds. https://www.climatebonds.net/market/data/#use-of-proceeds-charts ↵

- Flammer, C. (2021). Corporate green bonds. Journal of Financial Economics, 142(2), 499-516. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2021.01.010 ↵

- International Capital Market Association. (2021). Green bond principles. https://www.icmagroup.org/assets/documents/Sustainable-finance/2022-updates/Green-Bond-Principles-June-2022-060623.pdf ↵