1 Introduction

Jacquelyn Humphrey

Traditionally, finance theory has taught that investors consider only two dimensions when making decisions: risk and return. Therefore (financial) managers should manage a corporation with one goal in mind – maximise shareholder wealth – because this is what shareholders want. Similarly, fund investors desire fund managers to maximise alpha (or “beat the market”) because they want the highest return from their investment given the portfolio’s level of risk.

This proposition has several advantages. First, the (financial) manager’s task is simplified into just one goal: choose those projects or investments that will maximise shareholder wealth. Second, optimisation across only two criteria, return and risk, allows for elegant mathematical models of how the (financial) world works.

However, even casual observation shows that this view of investor decision-making does not reflect the reality of the complex world in which we live. For many investors, the decision-making process is far more nuanced, and will often include a multitude of factors. Many investors care about how the corporations in which they invest use money, in the same way as they would care about the activities they participate in, or the purchases that they make.

Only caring about return and risk has implications for how investment portfolios are designed and how companies are run. In this book, we will investigate how sustainability – largely in terms of environmental, social and governance (ESG) issues – can interact with making financial decisions.

ESG Issues

So what are the ESG issues that investors care about? Two recent surveys by the Responsible Investment Association of Australasia asked investors in Australia and New Zealand this question. Their answers are shown in the figure below. You can see slight differences in the answers from the two countries. You can also see that there are different ways ESG issues can be combined with financial decisions. The top part of the figure shows ESG issues that are important to investors when thinking about making investments. The bottom part of the figure shows the types of activities companies could be involved in that investors don’t want to put their money in. Both of these are important when looking at sustainable finance. (We will delve into the different ways of implementing ESG in Chapter 4.)

The Environmental and Social Themes Australian and New Zealander Investors Care About

Top 10 themes investors care about

| Australia | New Zealand | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Renewable energy and energy efficiency | Healthcare and public health and medical products |

| 2 | Healthcare and public health | Healthy rivers and ocean ecosystems |

| 3 | Sustainable water management | Sustainable water management |

| 4 | Healthy rivers and oceans | Renewable energy and energy efficiency |

| 5 | Zero waste and circular economy | Biodiversity |

| 6 | Sustainable land and agriculture | Sustainable land management |

| 7 | Employment and local business | Social and community infrastructure |

| 8 | Biodiversity | Zero waste and circular economy |

| 9 | Sustainable transport | Education and vocational training |

| 10 | Green, social and community infrastructure | Sustainable transport |

Top 10 issues investors do not want

| Australia | New Zealand | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Animal cruelty | Human rights abuses |

| 2 | Human rights abuses | Labour rights abuses |

| 3 | Animal testing for non-medical purposes | Environmental damage |

| 4 | Pornography | Violation of indigenous peoples’ rights |

| 5 | Environmental damage | Company tax avoidance |

| 6 | Company tax avoidance | Animal testing for non-medical purposes |

| 7 | Gambling | Social media companies that breach privacy standards |

| 8 | Tobacco | Intensive livestock management using cages and crates |

| 9 | Weapons and firearms | Weapons and firearms |

| 10 | Violation of indigenous peoples’ rights | Genetic engineering and toxic agri-chemicals |

Sources: RIAA From Values to Riches 2022: Charting consumer demand for responsible investing in Australia (PDF, 1.58MB) and RIAA Voices of Aotearoa: Demand for Ethical Investment in New Zealand 2023 (PDF, 3.2MB)

In 2022, the top expectation that Australians had of their financial advisors is that they were knowledgeable about ESG investment options, and for New Zealanders this was the second most important issue.[2] Further, most Australians and New Zealanders (83% and 74%) expect their superannuation and their bank to invest ethically and responsibly.[3] Clearly, investors care about more than just return and risk!

Market Size

In the West, sustainable finance started out as a small, niche market dominated by religious investors who wanted their investments to reflect their religious values. However, sustainable finance is now seen as having become almost mainstream. Indeed, the sustainable finance market has experienced phenomenal growth, particularly in recent years, across all asset classes and across all regions of the world.

According to the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), in 2022 the value of the sustainable finance market was US$5.8 trillion – an increase of 18% from the year before.[4] UNCTAD measures the sustainable finance market as comprising funds, bonds and voluntary carbon markets. The number of sustainability funds grew from 189 funds in 2012 to 7,012 in 2022.[5] Europe by far dominates the sustainable funds market (83% of sustainable funds under management are European). Voluntary carbon markets quadrupled in size over the 2012-2021 period. The sustainable bonds market, which is a newer market, grew 500% over the period 2017-2022.[6] We will learn more about sustainable financial instruments in Chapter 4.

Australia and New Zealand

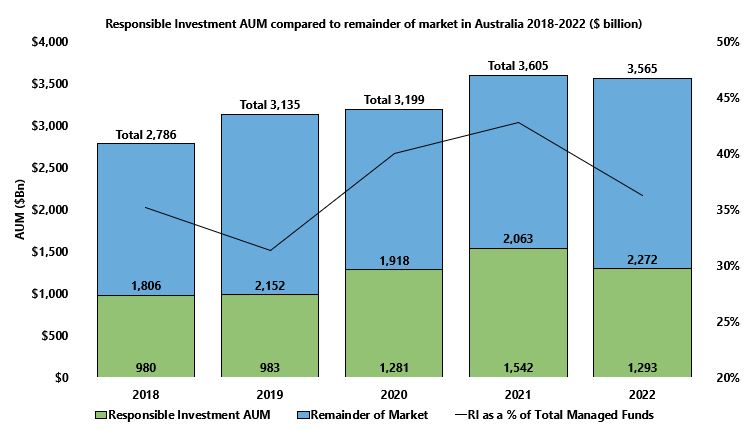

As with the rest of the world, ESG is becoming increasingly important in Australia and New Zealand. In 2022, in Australia, there was over $1.3 trillion in sustainable assets under management (AUM), or 36% of the fund market.[7] Compared to 2019, where Responsible Investment AUM was approximately $980m. Similarly, in New Zealand ESG AUM was $183 billion in 2022.[8] This represented over 52% of New Zealand’s total funds under management. Sustainable bonds markets are small, but growing, in these two countries.

Size of the Responsible Investment Market in Australia and New Zealand: 2018 to 2022

A Note on Terminology

The terminology in this area is somewhat slippery and has also changed over time. You may have heard the following terms relating to finance or investment:

- Socially responsible

- Ethical

- SEE (Social, Environmental and Economic)

These terms are slightly outdated. Today we would typically use the broad umbrella terms ESG, sustainable or responsible, and these are the terms we will use throughout this book.

You may also come across the term Corporate Social Responsibility, or for investment that specifically focuses on environmental issues, “green finance” or “climate finance.”

About This book

In the remainder of this textbook, we cover a range of topics in the area of sustainable finance.

Chapter 2 looks at ESG from the perspective of the organisation. Here, we will draw on your existing corporate finance knowledge and extend it to help you to think about how organisations can function in ways that better align with ESG.

Chapter 3 outlines some of the important sustainable finance initiatives and looks at how ESG is measured.

Chapter 4 views ESG from the perspective of investors. We will look closely at what type of ESG products are available in mutual fund and bond markets, and talk about how ESG strategies are implemented.

In the second part of the book, we will take a “deep dive” into two pressing contemporary issues: corporate transition to net zero emissions, and indigenous views of sustainable finance.

Chapter 5 explains the planetary boundaries framework and zooms into climate change which is arguably the greatest challenge humanity is facing, including how it relates to our economy, society and business. This is important to be able to understand Chapter 6.

Chapter 6 looks at how corporations need to transition to net zero emissions, including pathways to getting there and how to measure their progress.

Chapter 7 provides insight into one indigenous, specifically Māori, “worldview” and shows what implications this worldview has for financial decision-making.

Please remember this book is an introduction to sustainable finance. Each of the topics we cover could have its own textbook. It is however ideal for those who are looking for an introduction and overview on the topic and we hope you enjoy this book and learn a lot.

Review Questions

Complete the chapter review questions below to test your knowledge.

- Steverman, B. (2020, February 6). 'Everything is accelerating': Billionaire investor on a climate change crusade. The Sydney Morning Herald. https://www.smh.com.au/business/markets/everything-is-accelerating-billionaire-investor-sends-a-climate-change-warning-20200206-p53y62.html ↵

- Responsible Investment Association Australasia. (2022). From values to riches 2022: Charting consumer demand for responsible investing in Australia. https://responsibleinvestment.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/From-Values-to-Riches-2022_RIAA.pdf; Responsible Investment Association Australasia. (2023). Voices of Aotearoa: Demand for ethical investment in New Zealand 2023. https://responsibleinvestment.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/Voices-of-Aotearoa_-Consumer-Demand-2023-Report.pdf ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- United Nations Conference on Trade and Development. (2023). World investment report 2023: Chapter III Capital markets and sustainable finance. https://unctad.org/system/files/official-document/wir2023_ch03_en.pdf ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Note that ESG markets did experience a decrease in size in 2022, but this trend appears to be reverting to the "normal" increase in 2022. ↵

- Responsible Investment Association Australasia. (2023). Responsible investment benchmark report Australia 2023. https://responsibleinvestment.org/resources/benchmark-report/ ↵

- Ibid. ↵