7 Indigenous Values Shaping Sustainable Investment: A Case Study of Māori

Ella Henry, Aaron Gilbert and Ayesha Scott

TE REO MĀORI KARAKIA

The chapter’s authors begin by acknowledging our ancestors and our spirit:

| Kia tau iho | Let the strength |

| Te tauwhirotanga | And serenity |

| O te wāhi ngaro | Of our ancestors |

| E pai ai te nohotahi | Guide us as we gather |

| Ā tinana, wairua hoki | In body and spirit |

| Werohia te manawa | With compassion |

| Ki te tao o aroha | And care for one another |

| Kia whakamaua kia tīna | Let this be realised |

| Hui e, tāiki e | For all of us |

Chapter Overview

At the end of this chapter, you will be able to:

- Identify the commonalities and differences between Indigenous and non-Indigenous sustainability practices in an investment context

- Evaluate sustainable investment practices, acknowledging key Indigenous values including intergenerational timeframes and a broader range of (non-financial) investment objectives

- Illustrate Indigenous finance concepts using examples of Māori [1] investment entities

How to Use This Chapter

Our aim is to introduce you to how Indigenous investors integrate the way they understand the world (their Indigenous “worldview”) with fundamental financial concepts and extend our understanding of sustainable finance. We encourage you to dip in and out of the content as you need, skipping ahead and coming back to different sections as you have questions, and to suit your interests along with your study requirements.

You’ll find “Key Takeaways” and questions to answer dotted throughout, inviting you to deepen your learning and relate the information to your own life and career.

On language: For many concepts, there is no satisfactory or direct English translation, and you will see us use Māori language to accurately convey investing in a Māori context. Our intent is to enrich your learning, beyond existing financial frameworks, and have included additional web, audio, and video resources to suit your learning style. For NZ-based students, the entire chapter provides an important basis for working in Aotearoa New Zealand.

“We need to put all our money where our values are” – Villanueva (2021, p.10)[2]

Indigenous cultures tend to view the world as highly interconnected and interdependent – in harmony or balance. This philosophical perspective significantly shapes Indigenous culture and values, and in a financial context, distinguishes Indigenous investment from a ‘traditional’ Western (or Eurocentric) view of investment. The advent of sustainable investment has moved mainstream finance beyond a sole focus on financial returns and increasingly in line with Indigenous investors’ values.

While this move toward sustainable investing results in some alignment with Indigenous investment objectives, Indigenous perspectives continue to offer a different way of thinking about sustainability in finance and challenge current financial concepts. But how can non-Indigenous investors and finance professionals incorporate Indigenous values in managing their own investment portfolios?

Balancing multiple objectives, including harmony, sustainability, and collective benefit, lies at the heart of Indigenous investment decision-making. As finance professionals try to integrate non-financial objectives into their decision-making, the experiences of Indigenous investors offer insights for all sustainable investment managers.

This chapter covers:

- Indigenous views of finance, showcasing the values, intergenerational timeframes, and inherent sustainability practices of Indigenous investors and businesses.

- Three case studies of Māori investment entities as examples of Indigenous values informing investment practice.

- Explanations behind the broad range of (non-financial) investment objectives of Indigenous investors.

- A summary of the challenges and tensions that remain for investors.

We start by giving some background into Aotearoa New Zealand’s history and politics, including the impact of colonialism on the Māori economy, as the financial ramifications of European settlement for Māori influence their investing practice today. [3]

Māori History and Culture

A brief introduction to the history of the Māori economy and Iwi investment:

Renata Blair – The Māori Economy and Iwi Investment (YouTube, 21m56)

The first 12 minutes briefly describe Māori history and culture, and supplement Professor Ella Henry’s slides: Introduction to the Māori world Te Āo Māori (PPT, 363KB).

Read more about Māori history and culture by selecting the arrows:

Discovering Aotearoa (New Zealand)

Māori are one part of the Austronesian diaspora – the term for the group who first ventured into the South Pacific over three thousand years ago into what we now know as Polynesia. Archaeological, linguistic, and genetic evidence has found these travellers originated in Southeast Asia, with the strongest linguistic links to the Formosan languages. These Austronesian languages are found throughout Southeast Asia, from Taiwan to the Pacific, stretching as far as Madagascar in the Indian Ocean (Greenhill et al, 2008; Anderson, 2016).[4] [5] Chambers and Edinur describe the explorations as “a remarkable, but perhaps somewhat underestimated, series of human population movements lasting continuously for around 5000 years” (2015, p53).[6]

It is estimated that the people now referred to as Māori[7] began arriving in Aotearoa New Zealand from the 13th Century, in a series of canoe (waka) voyages. While the origins of these waka are uncertain, a combination of Māori storytelling (the primary repository of knowledge in a culture without written texts) and archeological evidence suggests more than one departure point. The location of Hawaiki, from ancient Māori mythology, may include Rarotonga, Tahiti, and/or Tuamotu. We do know that the view “held by the indigenous people themselves, is one of islands connected to each other by storylines and cosmologies to form a single cohesive unit, built on a history of ocean voyaging and knowledge transference to new environments” (Feary & Stubbs, 2012, p202).[8] We also know that at least one group of Polynesian peoples voyaged to South America, returning with the sweet potato, named kumara (Adds, 2008).[9] Taken together, this evidence shows that Māori brought physical, human, and cultural resources shared by other Polynesian peoples to the country, then adapted to the new geography and climate.

History also tells us that the first arrivals in Aotearoa New Zealand were adventurous and curious, adaptable, and innovative, and with the arrival of multiple waka (canoe) over many decades created a unique new society, based on an ancient culture and values, that subsequently developed into something unique and distinctive to Aotearoa (Walker, 1990).[10]

Māori Society

Traditional, pre-colonial Māori society was based on collective ownership and shared use of resources by groups living in tribal communities. This kinship was linked by whakapapa to founding rangatira and/or waka. The smallest social unit was the whānau, or extended family, usually made up of three to four generations headed by kaumātua. Rangatira were called upon to manage resource dependencies and other social matters (Henry, 1995).[11] According to Mika, elders in Māori society performed important roles as keepers of tribal knowledge, sources of mātauranga , child-rearing, and education. (2016, p. 168).[12] Collectives of whānau, living in communities close to each other, and bound by common ancestry, might form hapū, a slightly larger tribal entity. These hapū could come together for celebrations or in times of stress. Several hapū (community), tracing their lineage back to the waka and/or common ancestor, were known as Iwi, the largest tribal grouping (Henry, 2012).[13]

One of the earliest written documents in the Māori language was Te Wakaputanga (translated as the Declaration of Independence), first signed by a collective of chiefs in 1835. Henry and Wikaire state that this document, “articulated the aspirations of tribes to form a national polity, retain their tribal sovereignty, receive acknowledgement of their status from the British Crown, and the protection of their trading interests by the Royal Navy” (2013, p.61).[14]

In the Māori language version, Te Wakaputanga refers to the gathering of chiefs as “Te Wakaminenga o Nga Hapu o Nu Tirene”[15] (the confederation of hapū/tribes of New Zealand). It also refers to Nga Tino Rangatira o Nga Iwi (the self-determination and sovereignty of iwi/tribes). Thus, the terms hapū and iwi were both used to describe tribal entities. The tribes, be they iwi or hapū, were the cultural and spiritual center of life in a society that had not previously developed centralised government, or associated organisations of the state, such as those that deliver and administer military, justice, education, and health services. In the absence of a national legal code, the declaration was a symbol of nationhood, with the creation of a unified body to make laws, whilst continuing to maintain tribal independence at the community level. The use of the term “Declaration of Independence” in English mirrored the federal system in the United States and was likely an intentional choice given the number of American sealers and whalers visiting Aotearoa New Zealand at the time.

Aotearoa New Zealand was formally annexed as a colony of Britain after the Treaty of Waitangi was signed between Māori chiefs and Crown representatives on February 6th, 1840. Over ensuing months, several versions of the Treaty (in both Māori and English) traversed the country, eventually being signed by over 500 chiefs. The English version was fundamentally different and has been the cause of ongoing conflict and hostility between Māori and the Crown (Stokes, 1992; Stenson, 2012; Orange, 2015).[16][17][18] A key dispute between the versions relates to the degree of authority Māori ceded to the British. The English-language version of the Treaty states that Māori ceded sovereignty to the Crown, while the Māori version uses the term kāwangatanga (governance) as opposed to rangatiratanga (self-determination).

Federalism (as implied by a “Declaration of Independence”) is a sophisticated political system, allowing for national polity, alongside state sovereignty. On that basis, it defies logic that the same chiefs who signed Te Wakaputanga would have abdicated their sovereignty to the British Crown less than five years later when signing Te Tiriti o Waitangi (the Treaty of Waitangi). It seems more likely that the Māori chiefs assumed deepening their relationship with Britain under the Treaty would continue to strengthen international trade and prosperity (Henry & Wikaire, 2013).

However, the colonial experience of Māori has not borne out that theory (Walker, 1990).

Te Ao Māori (the Māori Worldview)

“Māori religion is not found in a set of sacred books or dogma, the culture is the religion. History points to Māori people and their religion being constantly open to evaluation and questioning in order to seek that which is tika, the right way. Maintaining tika is the means whereby ethics and values can be identified”

– Henare (1998, p3)[19]

By drawing on ancient Māori cosmological accounts, renowned Māori scholar Henare developed an analytical framework for describing traditional culture and values to better understand Māori society, given the lack of written historical records. Anderson reinforces Henare’s work, noting “the specifically tribal traditions of all Polynesians were often expressed in the formulaic language and metaphor of myth and legend” (2016, p24).

Specifically, Henare (1998) created a “Koru of Māori Ethics” (see Slide 7 in Henry’s slides above). Henare writes:

“like a koru on the fern, each ethic reveals an inner core as it unfurls, and they are the foundations of Māori epistemology and hermeneutics – knowledge and interpretation of oral traditions, events and history… Together they constitute a cosmic, religious worldview and its philosophy, from which can be identified an economy of affection and the utilisation of resources (that) aims to provide for the people in Māori kinship systems.”

– Henare (1998, p7)

The koru is the spiral of the silver fern frond, an image that is prevalent in carving and weaving arts, representing new life. The metaphor of the koru, unfurling like the cosmos, embodies the primary beliefs of the ancient Māori. At its centre is Io, the origin of all life, from which sprang Papatuānuku, the earth mother, and Ranginui, the sky father. Their offspring, the fronds of the koru, are atua, guardians of every facet of life and the human environment. Our celestial parents bestow gifts upon us, as do all parents. Tapu is the sacred, sacrosanct centre of all things. Mana, the spiritual power and authority that can be applied to people, their words, and acts, is closely linked to tapu. Mauri is the life force, the intrinsic essence of a person or object. Hau is the vital essence embodied in a person and transmitted to others, through everything they produce and value.

The Collective Responsibility versus the Individual Right

“Environment before People; People before Profit; Responsibility over Rights.”

– Temuera Hall, Portfolio Manager TAHITO

Mauss (1990) also described the intricate set of relationships surrounding kinship as an economy founded on reciprocity, where gift-giving was the glue that bound communities together. According to Stewart, “Mauss’s gift theory included the Māori example of the ‘hau of the gift’ which Mauss explained as a spiritual force, seeking to return to its original owner or place of origin” (2017, p1). This “economy of affection” was one in which the political economy related to the impacts and effects people had on each other and their environments, which was in direct opposition to the capitalist “economy of exploitation” introduced with British colonisation (Henare, 1995)[20].

Today, collectivism is demonstrated across all levels of Māori society, including joint Iwi ownership of key business assets. For example, many Iwi hold shares in Māori-owned Moana New Zealand, a fisheries company that owns half of Sealord, one of the largest fisheries companies in the Southern Hemisphere. This inter-Iwi collective arises from one of the earliest negotiated settlements with the Crown, recognising customary Indigenous fishing rights by endowing equal ownership in the (then Crown-owned) Sealord company to Māori.

The Impact of Colonisation

The traditional Māori economy contrasted sharply with 19th century British culture and society. In his comparison of Māori and Eurocentric knowledge and philosophy, ethnographer Elsdon Best wrote, “In studying the religion and myths of barbaric folk such as the Māori people of these isles, it is by no means an easy task to do so in a sympathetic manner. Our own point of view differs so widely”, (1924, p. 2).[21] He went on to note, “It is not a case of differing degrees of intelligence, for the Māori is a remarkably intelligent person; but of difference in outlook on life, on matters normal and supernormal, essentially the latter” (1924, p. 34). Views such as these, from eminent British scholars, no doubt contributed to the negative view of Māori and fostered the view that Māori should be assimilated into (British Colonial) society.

It took little time for overt (British Crown) government action to have an impact, including repressive legislation directed at appropriating Māori land, and open warfare resulting in the loss of land, language, and Indigenous culture. By 1900, Māori retained less than 10% of land in Aotearoa New Zealand, undermining the economic foundations of Māori communities. By the turn of the 20th Century, the population was so decimated by poverty and disease it was assumed the Māori would die out (Henry, 2012).

Māori did not die out, of course, but the oppression of Māori, their language and culture, has had a catastrophic impact. The result of colonisation is not only the loss of land and the loss of people through disease, poverty, and despair, but the loss of language, culture, cosmology, and identity. By the mid-1950s, Māori was a dying language and Māori people suffered the very real threat of death by assimilation. Over the same period, European settlers grew in wealth and opportunity, through expropriated land and the diminishing mana of the Māori people.

A Māori Renaissance

In the aftermath of the Second World War, Māori began an unprecedented urban migration. While enabling further assimilation, the migration also introduced increasing numbers of traditionally isolated and rural Māori to the institutions, the technologies, and the opportunities of the post-war economy. Māori became educated, wealthier, and empowered to the extent that by the 1970s, the Māori Renaissance was born and fully acknowledged (Walker, 1990). The Māori struggle was founded on demands for Māori sovereignty, acknowledgement of the Treaty of Waitangi as the constitutional basis of New Zealand society, and redress demands for Treaty grievances (Awatere, 1984).[22]

The Māori Land March in 1975 brought together diverse activist groups and Māori organisations to highlight the plight of Māori people. In the same year, the National government created a Tribunal to consider Treaty grievances. However, it was only in 1984 under the new Labour government that the Waitangi Tribunal was given the power to look retrospectively back to 1840 at breaches of the Treaty, and the potential to require the New Zealand government to address and produce redress for historical grievances (Henry, 2012).

Since 1985, successive New Zealand governments have devolved over 2 billion NZD to tribes (Iwi) in Treaty settlements, in partial redress for the harm caused to Māori by European settlers. These settlements have been key to enabling Māori investment and wealth creation today. Additionally, Māori have grown in political strength and unity, particularly since the 1993 introduction of proportional representation in the New Zealand political process. However, Māori still languish economically, socially, and culturally, when compared to non-Māori.

Movements such as the Te Kōhanga Reo (the Māori language early childcare system), Kura Kaupapa Māori (Māori language primary and secondary education), Te Whare Wānanga (Māori universities), Te Taura Whiri i te Reo Māori (the Māori Language Commission), Te Māngai Pāho (the Māori Broadcasting Authority), and a raft of other organisations have increased the potential for positive change (Henry, 2012).

Billion dollar Auckland iwi sharing part of its history in new tourism venture (YouTube, 1m51s):

Jan 4, 2018 – “Ngāti Whātua Ōrākei is hoping its tech-based tour of a city icon will help diversify its assets.”

Key Takeaways

Key Takeaway 1 – Everything is connected.

Ancient Māori knowledge is founded on the profound relationship between humankind and the cosmos, and the genealogical links that bind these. Everything is connected and interwoven into a pattern of evolution from the void at the beginning of time, to the world of light in which all life exists.

Key Takeaway 2 – Knowing history helps us make sense of now.

Traditional Māori philosophy and knowledge have endured to survive colonisation, albeit through change, and ancient knowledge continues to shape, inform, and serve Māori identity and action in contemporary society.

Questions

Think about your own culture, personal values, and your background. Answer:

- How do they influence your decisions? Choose two examples from the previous week to illustrate how you live your culture, values and/or make decisions influenced by your background.

- What relationship do you have with the world around you (people, places, nature etc)? Has it influenced your decision to study finance, sustainable finance, or learn about investing?

- Think about your personal investment objectives. Do you place financial returns before non-financial considerations (like sustainability)? Why/why not? How does your answer relate to your answers in (1) and (2) above?

Next, we offer Māori organisations’ investment strategies as examples of how uniquely Indigenous values shape sustainable investment.

Overlap Of Māori Values and ESG Concepts

Iwi (Tribe) Asset Management

Iwi typically manage their assets via Māori Asset Holding Institutions (‘MAHI’, also the Māori word for ‘work’) within a tribal entrepreneurship framework (Mataira, 2000).[23] The commercial entities manage Iwi assets within a Māori cultural framework for the current and future benefit of the tribe and its members.

“Mō tātou, ā, mō kā uri ā muri ake nei – For us and our children after us”

– Ngāi Tahu mission statement, 2023[24]

However, the consequences of colonisation (described in “The Impact of Colonisation”) for Māori, like many Indigenous populations, means they are disproportionately represented across many negative social statistics, including life expectancy and health outcomes, educational achievement and employment, and incarceration rates. The financial returns of MAHI are an important revenue source for Iwi, to support “social, cultural, educational, health and environmental programmes” (Tainui Group Holdings, 2023) aiming to improve overall wellbeing for Māori. Many Iwi, therefore, face an investment horizon trade-off between improving social outcomes for their current generation and building their economic base to provide for the next.

“Whakatupu rawa, whakatupu taangata – Growing assets to grow our people”

– Tainui Group Holdings purpose, 2023[25]

Example: Ngāi Tahu – Background and Investment Objectives

Based in Aotearoa New Zealand’s South Island (Te Waipounamu), Ngāi Tahu’s rohe (tribal lands) stretch from southeast of Blenheim, across to Kahurangi Point on the west coast, down past Bluff to also encompass Rakiura (Stewart Island). In terms of regional coverage, theirs is the largest of all Iwi (Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu, 2021), and one of the most populous with over 75,000 registered whānau members (Ngāi Tahu Group, 2022).[26]

In 1998, the Crown and Ngāi Tahu finalised their Treaty Settlement negotiations, including an apology from the Crown and $170m (land and cash). However, the Ngāi Tahu Charitable Trust and its predecessor, the Ngāi Tahu Māori Trust Board, have been managing and distributing Iwi assets since the mid-40s with a strategy of growth, value creation, and reinvestment.

Ngāi Tahu Holdings Corporation (NTHC) is tasked with “[protecting] and [growing] the pūtea [fund] and [delivering] a dividend” (Ngāi Tahu Group Annual Report 2021-2022, p.2), allowing fund distribution for Ngāi Tahu Charitable Trust. The Trust supports programmes related to education (including financial literacy), health, and whānau wellbeing, linked to the promotion and protection of culture and language.

The approach of having an “investment arm” and a “social arm” is not uncommon for Iwi, indicating the pragmatic melding of dual objectives within a non-Indigenous financial framework. For example, under their mandate to deliver sustainable investment returns, in FY22 the entire Group returned 9.8% and distributed 3.7% of Net Assets to the Charitable Trust.

There are challenges in the separation; with kotahitanga (unity) listed as an explicit Iwi value, and the trade-off between current and future time horizons a delicate balance. CEO of NTHC, Lisa Tumahai, acknowledges this in her 2022 report (Ngāi Tahu Group Annual Report 2021-2022, p.2): “I remain hopeful that collaboration between the Office [Trust] and NTHC will continue to grow. At times we can still feel like we are two very different organisations.”

Now, in 2023, the Iwi manages six subsidiary companies worth approx. NZD 1.89 billion (Ngāi Tahu Group Annual Report 2021-2022) and seeks to deliver on their 10-year plan ‘Ngāi Tahu 2025’. It is arguably the formal reinvestment policy (two-thirds of income), in place since the advent of the Trust, that most clearly demonstrates the ongoing intent “to create and control [their] destiny” (Ngāi Tahu 2025, p.5).[27]

An Overview of Māori Wealth

As noted earlier, colonisation decimated the Māori asset base via land confiscations (amongst other things), alienating Māori from their ancestral lands (rohe) which provided sustenance and economy. Māori wealth, that which was retained and has been rebuilt since, is mostly retained within Iwi structures, comprised of lands retained after British appropriations and confiscations, and the proceeds of Treaty settlements discussed above (see “A Māori Renaissance”). These settlements are negotiated with Iwi or hapū as restitution for historical breaches of the Treaty of Waitangi, and typically involve an apology from the Crown, the return of Crown-owned lands taken from the Iwi or hapū, and financial compensation. The value of Treaty settlements amounts to approximately NZD 2.6 billion across 85 settlements.

For eight of the ten largest Iwi, their largest investments are in either property or primary industries; most investments are in land and businesses that utilise land and sea (like the Sealord fisheries example in “The Collective Responsibility versus the Individual Right”), unsurprising, given the historical importance of land to Māori for resources, sustenance, and culture.

As of 2021, the value of Iwi-held assets was estimated at NZD 11.7 billion although the broader Māori economy, including Māori-owned businesses, is valued closer to NZD 70 billion. The 10 largest Iwi collectively hold about 69% of all Iwi assets. In terms of assets under management, the three largest Iwi are Ngāi Tahu (2.2B), Waikato-Tainui (1.9B) and Ngāti Whātua Ōrākei (1.6B), see TBD Advisory (2022).

The intent of each settlement is that they are final, meaning there will unlikely be additional significant transfers from the Crown to Iwi as the process winds down. For Iwi, it is crucial that their treaty settlements are managed effectively for their people’s ongoing health and wellbeing. This highlights risk management as a significant consideration for Iwi investment managers; losses to the asset base of the Iwi cannot be easily replenished.

Key Takeaways

Key Takeaway 3 – Overall Value

The Māori economy is estimated to be worth NZD 70 billion, including tribal (Iwi) assets and Māori-owned businesses. In 2021, Iwi-held investments were valued at NZD 11.7 billion and are typically managed via holding institutions known as MAHI (Māori Asset Holding Institution).

Key Takeaway 4 – Importance of Financial Returns

Financial returns are an important revenue source to support and improve overall wellbeing. Māori, like many Indigenous populations, are disproportionately represented across many negative social statistics, including life expectancy and health outcomes, educational achievement and employment, and incarceration rates. There is an investment horizon trade-off between improving social outcomes for the current generation and building the economic base for the next.

Key Takeaway 5 – Addressing Dual Objectives

Iwi often use a two-pillar approach in a non-Indigenous financial framework to manage their now with their future, referred to as having an “investment arm” and a “social arm”.

Key Takeaway 6 – Risk Management is Key

Sound risk management is crucial for Indigenous investors, like Māori, as they manage current and future needs along intergenerational time horizons.

Questions

- List two examples of non-Indigenous investment entities that typically have long (intergenerational) time horizons. Briefly describe how they approach building their asset base while providing income streams to their investors (or similar) now.

- What is the size of your local Indigenous economy? How does it compare to the national economy? If investment funds like MAHI exist, provide an example.

- If needed, review what you’ve previously learned about ESG (Environment, Social, Governance) in business and finance.

Cultural Values Underpin Māori Business and Investment

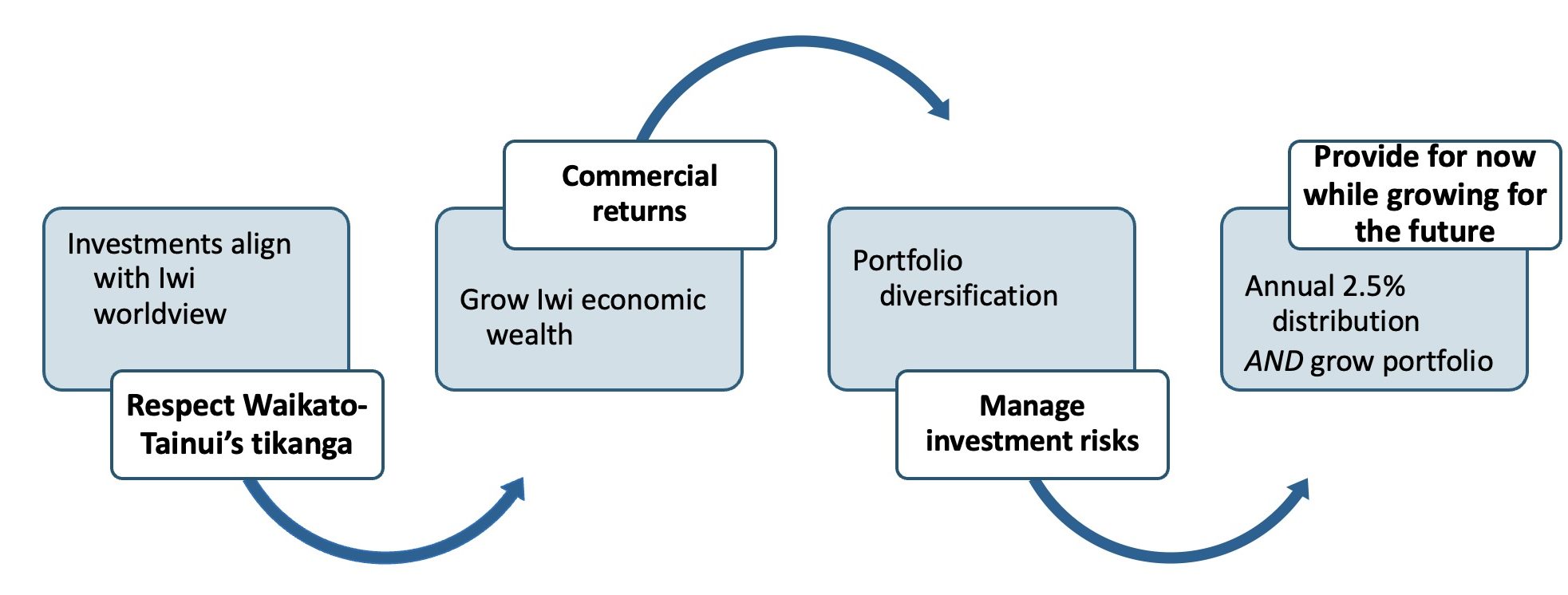

MAHI operate within Te Ao Māori (Māori worldview). For instance, (Waikato-)Tainui Group Holdings (TGH) operates within Puna Whakatapu Tangata, a holistic framework setting out their investment portfolio objectives. The blueprint emphasises four pillars underlying the TGH’s investment strategy, shown in the figure below, beginning with respect to tikanga (customs and traditional values of Waikato-Tainui). Ngāi Tahu frames a similar imperative as “respecting and contributing to the mana (prestige) of Ngāi Tahu” (Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu, 2023). In both cases, the implication of beginning with tikanga and mana is that Māori values will, alongside economic returns, drive all financial decision-making.

Source: adapted from Waitkato-Tainui’s Puna Whakatapu Tangata (Investment Framework).

We noted previously the importance of mana (spiritual power and authority, applied to people, through their words and acts) and hau (the vital essence embodied by a person and transmitted to others, through everything they produce) to Māori culture. Through building and growing their economic foundations, Iwi aim to build and grow their mana.

Mana is a familiar concept to both Māori and other Polynesian peoples, with Dwayne “The Rock” Johnson offering this explanation to journalist Jacqui Brown in 2017:

Mana is a term in Polynesian culture – it’s spirit, it’s power. Everyone in New Zealand has [their] own version of mana. I feel like the most important thing about mana is it’s very grounding. It makes you recognise how grateful you should be, recognise your blessings because [life] wasn’t always like cool fun, bright lights and movies…

– Dwayne “The Rock” Johnson, 2017

A third related concept relevant to investment frameworks is taonga, which translates to ‘treasure’. Taonga has a very broad definition, encompassing both tangible things including land (whenua), its natural resources, scared (tapu) and significant places (like marae, the community centre of hapū) – like the Western concept of ‘assets’ – and intangible things, like te reo (language) and tikanga (Russell et al., 2012).[28] Māori are guardians of taonga, rather than owners, implying it is their responsibility to protect and enhance it for future generations’ benefit.

Kono NZ Seafood Story

These three videos introduce the story of Kono Seafood. Part 1 (Linkedin, 1m05s) focus on their why – why they share the best of their place and space with the world. In Part 2 (Linkedin, 1m08s), they share the connection between kaimoana, seafood and togetherness. In Part 3 (Linkedin, 1m43s) they visit the home of their Greenshell Mussels and we learn how they balance growing resources with being good ancestors.

While this idea arguably places Māori investors alongside impact investors, and well within current understandings of ESG, by framing their purpose as both future-focused and within tikanga, Indigenous investors like Māori extend beyond standard (non-Indigenous) sustainable investment.

Actions consistent with tikanga , especially in preserving and enhancing taonga, enhance mana.

The focus on enhancing financial and non-financial taonga to benefit everyone involved is akin to stakeholder theory, although for MAHI, investments must especially benefit the Iwi and its members. For Māori investors, their financial returns must align with non-financial objectives including the support of their people today and building a better future for their people tomorrow.

Exercise – Actioning Values Guide Investment Decisions

Key Takeaways

Key Takeaway 7 – Prioritising Values

Indigenous investors, like Māori, prioritise non-financial considerations (including environmental, social, and spiritual factors) over financial performance in their investment decisions. Leading decisions with their values helps to ensure the resulting portfolio aligns with their sustainability and non-financial goals.

Key Takeaway 8 – What is an ‘Asset’?

Indigenous investors, like Māori, aim to invest in both tangible assets (like land or businesses) and intangible assets (like culture and language).

Key Takeaway 9 – Above and Beyond

While similar in some ways to non-Indigenous impact investors, Indigenous investors go beyond protecting what we have now (e.g., our waterways or biodiversity via sound environmental practice) to actively improve it for tomorrow. This can include building portfolio wealth for the next generation (recall Ngāi Tahu’s example above) or investing directly in businesses making the world a better place (e.g., circular economy).

Questions

- Compare and contrast: What do Indigenous investors (like Māori) have in common with impact investors? How are they different? Use an example or examples to illustrate your answer.

- How does stakeholder theory relate to a Māori investment or business approach? Use an example or examples to illustrate your answer.

Values: Expanded

| Value | Description |

|---|---|

| Whanaungatanga (relationship and kinship) | Whanaungatanga recognises the bonds and relationships between people. Māori culture places considerable importance on familial and ancestral bonds, placing people within wider social networks. A person is therefore accountable to a wider community, resulting in a more collective view of the world. Assets belong to the collective, rather than an individual, and should benefit the collective. Whanaungatanga (relationship and kinship) also places great importance on relationships. Within a business context, these relationships create both opportunities and obligations (Haar and Delaney, 2009). Interlinked with whanaungatanga (relationship and kinship) is the concept of manaakitanga (care for all things), which arguably sits at the heart of how Māori view relationships. |

| Manaakitanga (care for all things) | Manaakitanga refers to caring for all people, with generosity and respect, and is commonly associated with hospitality. Manaakitanga (care for all things) is about growing the mana (spirit/power) of others, and by doing so results in mutually beneficial relationships. An investment preference for long-term, direct holdings in businesses suggests these relationships are more valuable than shorter-term indirect investments. The overarching investment goal of Māori to look after their tribal members, their hapū (community) and whānau (extended family), and support their wellbeing is practising manaakitanga (care for all things). The example provided below of Ngāi Tahu demonstrates what manaakitanga (care for all things) looks like in an investment and business context. It is perhaps most like the Social pillar of the ESG framework, with its focus on people, and in a non-Indigenous business setting can be thought of as caring for employees and consumers. |

| Kaitiakitanga (stewardship/guardianship) | Kaitiakitanga relates to being a guardian of taonga (treasure) and is often used to describe environmental stewardship. In this respect, it incorporates the Environmental component of the ESG framework. However, kaitiakitanga (stewardship/guardianship) goes further as it incorporates both socio-economic and cultural issues. As a result, kaitiakitanga (stewardship/guardianship) also relates to the Social aspect of ESG, looking after and caring for communities. Additionally, where the ESG framework focuses on minimising harm and maintaining our environment, kaitiakitanga (stewardship/guardianship) requires the improvement of the taonga (treasure) entrusted to a person or community. On the face of it, kaitiakitanga (stewardship/guardianship) appears to carry a stricter standard of stewardship than the current risk management focus on material ESG issues. |

| Wairuatanga (spirituality) | Wairuatanga relates to Māori spirituality and their understanding of their place within the universe, earth, and land (Hall et al., 1993). An important aspect of wairua (spirit) is the connection to ancestors, especially through connection to ancestral lands. The alienation of Māori from their lands via confiscation and urban migration caused considerable harm to Māori wairua (spirit). Within MAHI, wairuatanga (spirituality) can be seen in the importance placed on retaining or acquiring additional land. For example, Waikato-Tainui’s whenua (land) policy requires that any divestment of land be balanced with an equivalent acquisition of whenua (land) within 18 months. Policies specifying land acquisition by MAHI recognise the hurt to Māori wairua (spirit) through its loss and clearly distinguish Indigenous investor goals from non-Indigenous investor objectives. |

| Kotahitanga (unity) | Kotahitanga refers to building unity between people, binding people together and encouraging consensus between parties. As a collective culture built on reciprocity and relationships, Māori business practice often refers to the waka (canoe) and joint goals. As we saw in the Ngāi Tahu example above, unity between the ‘social’ and ‘investment’ arms is key to the enduring success of the Iwi (tribe). |

Example: Ngāi Tahu – Practising Values Through Investment

Along with the values above, Ngāi Tahu add tohungatanga (expertise) and rangatiratanga (leadership). Test your understanding by matching Ngāi Tahu’s values to their explanation, sourced from their Annual Report 2022.

Values Trade-off

The balancing of manaakitanga (looking after Iwi members) with kaitiakitanga (stewardship/guardianship) of current and future assets, is exemplified by Ngāi Tahu’s decision-making during the COVID-19 pandemic and associated economic downturn that impacted aspects of their business, especially tourism. For example, they paused some regular grant funding distributions due to economic volatility over 2020-2021 and switched focus to natural disaster and pandemic-related relief for their community, like many corporate organisations with social responsibility programmes.

The preference for relatively large, direct holdings in companies allows the active practice of whanaungatanga in an investment context. These longer-term business relationships and partnerships also provide opportunities for self-determination and control important to Māori generally. However, diversification still needs to be managed to avoid over-exposure and illiquidity.

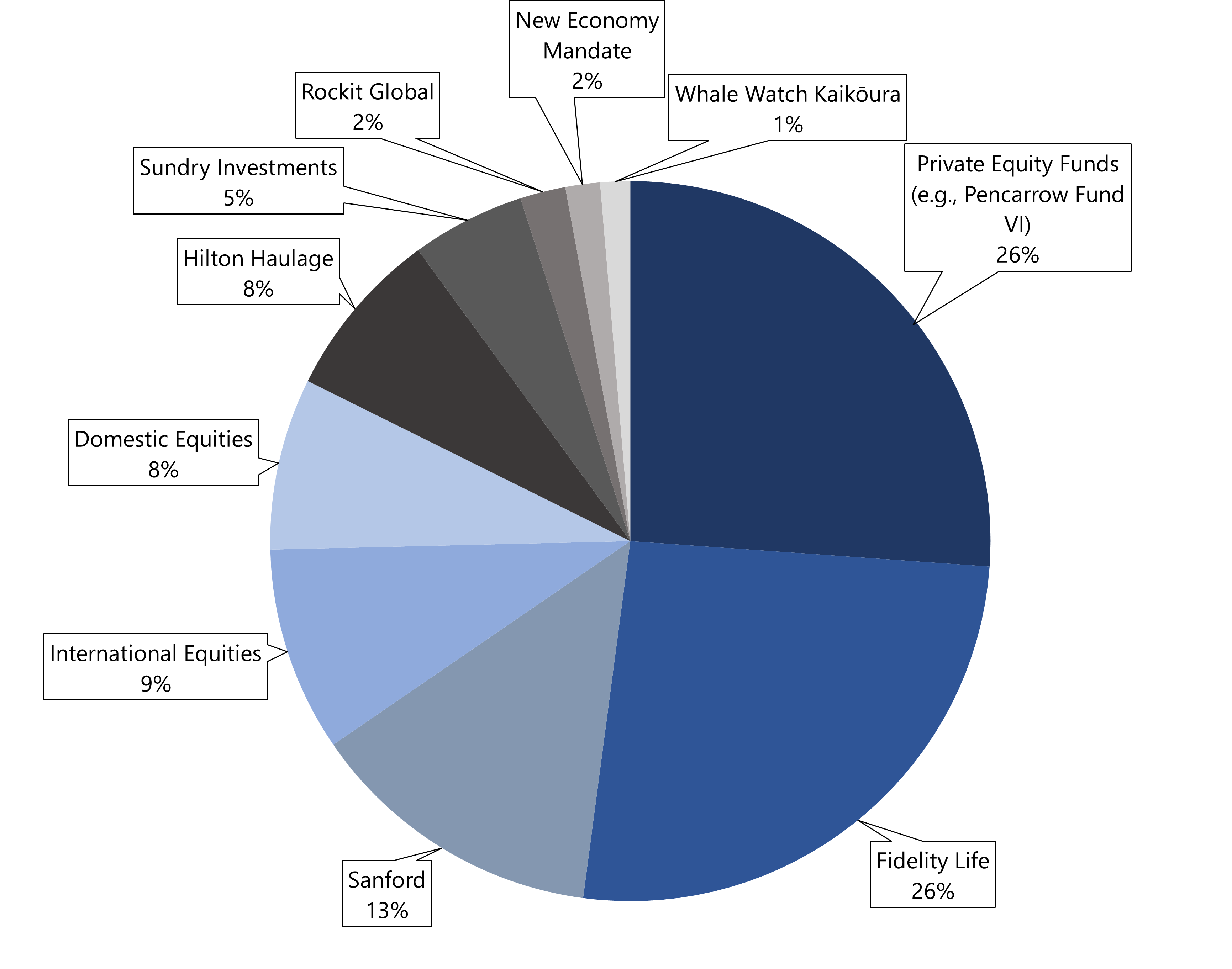

Investment in Practice – Kaitiakitanga and Tohungatanga

Ngāi Tahu Holdings Corporation (NTHC) encompasses their business arm (in seafood, property, farming, and tourism), direct investments in NZ businesses (e.g., their 24.9% stake in life insurer Fidelity Life, or 50% stake in transport company Hilton Haulage), ESG-focused indirect holdings (e.g., Pathfinder Responsible Investment Fund). While their preference is investments in NZ-based business, with a particular focus on Te Waipounamu (South Island), the portfolio includes some international holdings like equities and the Australian operations of their seafood company.

We focus here on their indirect holdings, managed by Ngāi Tahu Investments (NTI), and worth NZD 573.4 million in total assets for FY2022 (second only to the Property subsidiary, worth NZD 754.9 million). Overwhelmingly, the NTI portfolio is NZ-based with a small (unspecified) holding in Australian assets – notably, international equities are less than 10% of total assets. NTI’s top holdings for the 2021-2022 financial year were:

Of note is the NZD 8.9 million in their New Economy Mandate portfolio, managed by a Ngāi Tahu-affiliated boutique financial advisory firm (NTI owns a 25% stake); the thematic portfolio considers “new economy” investments like the circular economy and alternative proteins. The values evident are:

- tohungatanga (expertise) – by investing in and managing funds through an Iwi-affiliated advisor, NTI is enabling expertise to be built “in-house”

- rangatiratanga (leadership) – novel technologies such as those broadly defined as “new economy” illustrate a future focus and position the Iwi as a leader in the field

- kaitiakitanga (stewardship/guardianship) – while managing large property and agricultural businesses, investment in new technologies like alternative proteins diversifies current and future revenue streams, building economic resilience.

Almost 17% of assets under management are held in an NTI-managed portfolio of listed equities. The investment approach is ESG-focused, with exclusionary screening that targets ethical practice, climate change, and sustainability to ensure Ngāi Tahu values are upheld. The investment purpose is to allow NTI to control what they are invested in while providing a liquid means of diversification.

Integrated Reporting:

NTHC reports their Scope 1, 2, and 3 carbon emissions and is implementing year-on-year carbon footprint reduction policies across their commercial businesses. Like all sustainable investors, their largest challenge is the Scope 3 emissions they cannot control (as they are generated through the supply chain, rather than directly by NTHC-owned businesses).

A Note on Individual Savings – Manaakitanga in Practice

Along with their commercial business, Ngāi Tahu also encourages Iwi members to invest personal savings in diversified portfolios via the Whai Rawa managed fund to increase financial capability, experience, and longer-term planning (often matching those savings with charitable trust distributions; over 16 years, these contributions equate to NZD 50 million). In FY23, Whai Rawa reported NZD 132 million in net assets across 33,255 members (Whai Rawa, 2023)[29].

These personal savings are managed by Mercer (NZ) Ltd, with investments in socially responsible conservative, balanced and growth portfolios according to the savings goal, and with clear withdrawal criteria (tertiary education, first home purchase, retirement [55+] and other special circumstances, like financial hardship). Like NTI, Whai Rawa investments exclude “sin” stocks[30] and seek to include “good” companies, with the SIPO stating that a “sustainable investment approach is more likely to create and preserve long term investment capital” (Whai Rawa Unit Trust Statement of Investment Policy and Objectives 2022, p.5)[31].

Further, and importantly, the SIPO includes a Responsible Investment Policy outlining that investments should be “consistent with Ngāi Tahu values and […] not undermine environmental stewardship, consumer protection, human rights, or racial or gender diversity” (p.5). It also emphasises active ownership as a key guiding investment principle.

Key Takeaways

Key Takeaway 10 – Diverse Values and Approaches

Like all portfolio managers, each tribal (Iwi) investment fund has its own investment values, goals, and priorities. For example, Ngāi Tahu includes tohungatanga (expertise) and rangatiratanga (leadership) rather than wairuatanga (spirituality).

Key Takeaway 11 – Transparency by Design

The Statement of Investment Policy (SIPO) outlines the investment approach to responsible investment – often, these types of investment strategy documents are more explicit than responsible investment policies for non-Indigenous fund managers and portfolios. Exclusion lists tend to be more extensive than non-Indigenous investment portfolios and may be adhered to more strictly.

Questions

Recall the Māori (investment) values are: Whanaungatanga (relationship and kinship); Kaitiakitanga (stewardship/guardianship); Wairuatanga (spirituality); Manaakitanga (care for all things); Kotahitanga (unity).

Māori Investment in Practice

The example provided in the previous section illustrates an Iwi (Ngāi Tahu) investment approach, offering a practical overview of how non-Indigenous ESG interacts and overlaps with Māori values. Here, we provide two additional case studies – a company, Wakatū Inc., and a managed fund provider, TAHITO – to round out the chapter.

Case Study One: Wakatū Incorporation

“Our purpose is to preserve and enhance our taonga for the benefit of current and future generations.”

– Wakatū Inc. purpose, 2020[32]

Background

In contrast to Ngāi Tahu’s approach, Wakatū Inc. was established in 1977 as an alternative to a charitable trust entity, allowing its owners (shareholders) to receive dividends from the company rather than grants or distributions (“Establishment of Wakatū”, 2020). With roughly 4000 registered whānau (extended family) members across four Iwi in the Nelson-Marlborough region at the top of Te Waipounamu (NZ’s South Island), Wakatū Inc. manages the “Nelson Tenths”[33] – some 1393 hectares of land in Nelson, Motueka, and Golden Bay, originally worth NZD 11 million (unimproved land value) – through three commercial subsidiaries:

- Whenua Ora – Approx. 70% of Wakatū, with an asset base of land and waterways, managed as a diverse property portfolio of residential and commercial buildings, orchards, marine farms, and vineyards. Wakatū’s “social” programmes, including home ownership, education, and wellbeing, are also run through Whenua Ora.

- Kono – A food and beverage business, with operations covering the farm-to-table supply chain across their product lines of wine, cider, beer, apples, pears, and kiwifruit.

- AuOra – Health and wellbeing business, using active ingredients from natural resources in and around Wakatū.

Today, Wakatū Inc. has an estimated value of over NZD 350 million (Wakatū Inc., 2020).

Investment in Practice – Kaitiakitanga

“Whatungarongaro te tangata toitū te whenua – As people disappear from sight, the land remains”

– Kono (Wakatū Inc.) on kaitiakitanga, 2022

Sustainability through kaitiakitanga is Wakatū’s dominant investment value and is emphasised across their mission, investment, and business philosophy (see, e.g., Kono’s Sustainability website for examples). They explain the collective responsibility to protect and enhance their “precious natural resources that are [their] life force” to “achieve sustained spiritual, environmental, social and cultural well-being and economic aspirations” (Kono, 2022)[34].

The focus on wairuatanga and culture in addition to general environmental and social concerns typifies a key difference between Indigenous and non-Indigenous investors, including sustainable and impact investors.

Kaitiakitanga is also exemplified by their 500-year plan (named Te Pae Tawhiti), which “sets out our purpose as an organisation. The reason we exist and what we want to do. A long-term plan like this is fairly common for Māori, we tend to think of our grandchildren and future generations” (Kerensa Johnston, Wakatū CEO, quoted in Brown, 2018).[35]

Placing values front and centre is evident through the Kono product range, with wine ranges named for and “inspired by” concepts like whenua and manaaki (Tohu Wines, 2021). There are parallels between Māori-owned businesses like Kono and non-Māori businesses founded with sustainability and social responsibility in mind, who often promote their philosophy strongly, too. For example, non-dairy ice cream and milk brand Little Island’s homepage prominently display their organic, vegan, fairtrade, and living wage employer credentials (Little Island “Our Story”, 2023).

Questions

Identify an example of a (non-Indigenous) sustainable company and answer:

- Provide a brief overview of your chosen company. Include the company’s mission and/or business philosophy and highlight the areas of sustainability and social responsibility they focus on.

- Compare and contrast: List similarities and differences between Wakatū (or one of their subsidiary companies, e.g., Kono) and your chosen company. Provide specific examples from each company to illustrate your answers.

- Wakatū has a 500-year business strategy. Briefly explain what Indigenous investment value or values this approach exemplifies and why.

- Think about your chosen company. Would a long-term (intergenerational) plan suit their business? Justify your answer.

Case Study Two: TAHITO

Funds manager TAHITO is “an Indigenous contribution towards a new global story of diversity, equity and sustainability”, focusing on “providing high quality ethical investment services” (TAHITO “About Us”, nd and “Investment Philosophy”, in Statement of Investment Policy and Objectives 2023, p.5)[36], guided by a Māori worldview.

They invest in NZ and Australian equities, targeting a 49%/49% split with 2% cash and cash equivalents, benchmarking to a 50-50 S&P/NZX50 and S&P/ASX200 Index (TAHITO Statement of Investment Policy and Objectives 2023). The fund holds Responsible Investment Association Australasia (RIAA) accreditation and in 2023 was awarded “Best Ethical Retail Investment Provider” by NZ-based Mindful Money (TAHITO Monthly Report August 2023). TAHITO reported NZD 21.5 million assets under management for the quarter ending June 2023 (TAHITO Quarterly Fund Update June 2023).

TAHITO details their strategy as one of active ownership in companies that are positively screened into the fund, after passing an initial negative screen. Their SIPO outlines a decision-making process based on ESG integration, with three investment priorities applied in this order:

- Values-based investment: the portfolio aligns with TAHITO principles.

- Impact investment: seek to “drive change” on social and environmental factors.

- Risk management: use ESG integration to reduce and manage the fund’s risk profile.

The way TAHITO describes their decision-making process highlights a key difference between an Indigenous investment fund and a non-Indigenous ESG or responsible investment fund. First and foremost, Māori values and worldview underpin the fund’s investment philosophy – before standard ESG screens are applied, as would be the case for non-Indigenous funds.

Second, ethical considerations are the primary filter through which investments are analysed. Financial performance and fundamentals are a clear secondary consideration, which is unlikely to be the case for many non-Indigenous funds claiming to be “responsible” (with some notable exceptions). The growing green- and impact-washing literature attests to the wide spectrum of ethical intensity among managed funds.

TAHITO define their approach as “a unique way of measuring companies using Indigenous knowledge combined with conventional financial analysis” (TAHITO “Indigenous Investing”, nd)[37]. In this sense, TAHITO demonstrates the purpose of this chapter and provides a roadmap for investors wishing to apply a values-based approach to their own portfolio management.

Question

There are seven steps in TAHITO’s Investment Process, but in the figure below they are out of order. Rearrange the steps into their correct order. In each case, provide a brief justification for your choice with reference to the principles of Indigenous investment covered in the chapter and TAHITO’s Case Study.

Challenges for Indigenous Investors

Like their non-Indigenous counterparts, Indigenous investors face challenges in aligning their values with their investment strategy. Specifically:

- Geographical diversification

- Lack of control over indirect holdings

- Reporting non-financial performance

- Defining value

Geographical Diversification

The Iwi-level, company-level, and funds manager-level case studies all demonstrate a preference for local (to Aotearoa New Zealand) and nearby (primarily Australian) investments. Within Aotearoa, investing in businesses and property tied to their tribal lands (rohe), aligning with whanaungatanga, may reduce diversification further and increase a portfolio’s risk profile. For example, Ngāi Tahu’s large holdings in tourism and agricultural businesses leave them exposed to natural disasters, like the 2016 Kaikōura earthquake, specific to the Te Waipounamu (South Island) region. Waikato-Tainui, in the central North Island, faced record rainfall in 2022-2023 and Cyclones Hale and Gabrielle, impacting their infrastructure and agriculture businesses, as well as their people (Waikato-Tainui Annual Report 2023).

An ongoing challenge for Indigenous investors is balancing their commitment to their geographical region while pursuing opportunities outside it. Additionally, relatively large weightings in property and land-based businesses also restrict industry-level diversification opportunities; heavy investment in farming, for instance, increases portfolio exposure to food and dairy price movements, and climate risks.

A Lack of Control Over Indirect Holdings

While Indigenous investors strive to meld their worldviews with Western financial principles and earn financial returns to support other activities, limitations of ESG reporting and transparency in company supply chains mean similar challenges exist for Indigenous investors, as they do for all responsible investors. These limitations are especially felt when relying on third-party managers and low-cost index investments.

Reporting Non-Financial Performance

Poyser et al. (2021)[38] highlight a key tension between Indigenous and traditional (Western) investment frameworks, particularly around reporting performance. While Māori Statements of Investment Policy and Objectives (SIPO) documents barely mention financial performance metrics, instead focusing on values and tikanga (traditional customs/values), investment strategy documentation tends to be dominated by financial performance measures. Poyser et al. (2021) suggest the difference lies in the documents’ purpose: a SIPO is aspirational, while a strategy is meeting disclosure expectations. However, this disconnect raises a key question for disclosure’s role and documents like the annual report.

Even when integrated reporting and the quadruple bottom line build in non-financial performance, do existing measures serve the broad and diverse outcomes Indigenous investors are concerned with? This in turn raises the question of whether documents like annual reports, even with integrated values-based, spiritual, and cultural reporting, serve investors well when reporting such a broad and diverse range of outcomes. For instance, how do you report on the wairua (spirit) of the Iwi?

Defining Value

Along with performance evaluation a challenge, shared by non-Indigenous impact investors, is how value is defined. Mika et al. (2022) argue that Indigenous views of value centre on collective wellbeing and contain both spiritual and material elements. Taonga encapsulates this difficulty, as what is prized and treasured contains not only material goods that can be assessed to hold a “market value” (like land), but also intangible elements that cannot be valued easily, if at all. Mika et al. (2022) put forward a Māori theory of value, based on the joint concepts of mana (spirit/power) and hau (life essence). However, how investors can incorporate such theory into both their decision-making and performance measurement requires more work.

Summary

Despite the tensions arising when considering an Indigenous worldview and values in an investment context, non-Indigenous sustainable investors can draw inspiration from the practice of Indigenous investors. In this chapter, we provided insight into one Indigenous history and context – that of Māori in Aotearoa New Zealand – and showcased how their investment strategy and objectives align with their values.

We focused on Iwi investment and Māori business here, however, many public NZX-listed companies in Aotearoa New Zealand now integrate the values described above in their annual reports and company mission statements. Values such as kaitiakitanga (stewardship/guardianship) and manaakitanga (care for all) are increasingly present across sustainability frameworks for all organisations, their sustainability plans, and organisational culture. The use of Māori terms like kaitiakitanga is also increasing within business contexts (in Aotearoa New Zealand). While it is questionable whether the concepts are entirely understood, there is evidence that businesses (and the financial sector) are moving to embrace these concepts.

The ongoing revitalisation of the Māori world is also being experienced by other Indigenous peoples. Award-winning Indigenous author Villanueva (2021), renowned Native American activist and expert on wealth and philanthropy, acknowledges money is nothing more than a human-created concept and tool for assigning value. He advocates for new strategies to use money in ways that can heal trauma and return balance, calling for people to create new “decision-making tables, rather than setting token places at the colonial tables” (p10).

Final Key Takeaway

In expanding our notion of “value” and “values” in finance beyond Western and Eurocentric theory and frameworks, we continue to expand our understanding of sustainable finance and its application.

Further Reading

If you would like to learn more about Māori culture, language, or values within a business context, below are some resources for you.

NZ-based readers will find the Māori language and culture material/apps particularly useful and applicable for working in NZ.

Video/Podcast Resources

- NZTE Investment Fix Season 3 Episode 5 [33 minutes]: Māori investment strategy with Rachel Taulelei and Jamie Tuuta, then listen on Spotify or Apple podcasts

- Extended interview (YouTube, 54m 38s) with lawyer and former Kono CEO Rachel Taulelei on Indigenous 100 about her career, international trade, sustainability, and business (Mahi Tahi, posted 24 October 2023),

Online Resources

- Māori culture and values in business, Te Kete Ipurangi (NZ Ministry of Education),

- Principles from Te Ao Māori (the Māori worldview), Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment.

- Tikanga Māori Values, explained by Rangatahi Tu Rangatira with activities.

Apps (Available on Android & Apple, via Your Favourite App Stores)

Available for free:

- Rongo, learning to pronounce te reo Māori

- Te Kete Māori, NZTE introduction to Māori culture

- Puna Ako, NZ Treasury introduction to Tikanga Māori

Available for free via an internet browser, the full functionality app is paid:

Te Aka, Māori dictionary and other learning resources.

Review Questions

Complete the chapter review questions below to test your knowledge.

- Māori are the Indigenous people of Aotearoa New Zealand. ↵

- Villanueva, E. (2021). Decolonizing wealth: Indigenous wisdom to heal divides and restore balance (2nd ed.). Barrett-Koehler Publishers. ↵

- Mika et al. (2022) highlight that Māori, the Indigenous people of Aotearoa New Zealand, share commonalities with other Indigenous peoples around the world. However, all Indigenous peoples have their own history and culture, distinct from each other, and while we restrict our discussion to Māori, we acknowledge unique contexts as critically important. Mika, J. P., Dell, K., Newth, J., & Houkamau, C. (2022). Manahau: Toward an Indigenous Māori theory of value. Philosophy of Management, 21(4), 441-463. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s40926-022-00195-3 ↵

- Greenhill, S. J., Blust, R., & Gray, R. D. (2008). The Austronesian basic vocabulary database: From bioinformatics to lexomics. Evolutionary Bioinformatics, 4, EBO.S893. https://doi.org/10.4137/ebo.S893 ↵

- Anderson, A. (2016). The first migration: Māori origins 3000BC–AD1450 (Vol. 44). Bridget Williams Books. ↵

- Chambers, G., & Edinur, H. (2015). The Austronesian diaspora: A synthetic total evidence model. Global Journal of Anthropology Research, 2(2), 53–65. https://doi.org/10.15379/2410-2806.2015.02.02.06 ↵

- The word Māori means ‘normal’, which was how the people described themselves when Europeans first made landing in the 18th Century. A dialect variation of the term is used across Polynesia: Māohi in Tahiti, Maoli in Hawai’i, Maori in Rarotonga. ↵

- Feary, S., & Stubbs, B. J. (2012). From Kauri to Kumara: forests and people of the Pacific Islands. In Australia’s ever-changing Forests VI: Proceedings of the eighth national conference on Australian forest history (pp. 202-207). ↵

- Adds, P. (2008). The arrival of the kumara. In Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand. ↵

- Walker, R. (1990). Ka whawhai tonu matau: Struggle without end. Penguin. ↵

- Henry, E. (1995). Contemporary Māori business and its legislative and institutional origins. In J. Deeks & P. Enderwick (Eds.), Business and New Zealand Society. Longman Paul. ↵

- Mika, J. P. (2016). The role of elders in Indigenous economic development: The case of Kaumātua on Māori enterprises of Aotearoa/New Zealand. In Indigenous People and Economic Development (pp. 151-175). Routledge. ↵

- Henry, E. (2012). Te Wairua Auaha: Emancipatory Māori entrepreneurship in screen production. Doctoral dissertation, Auckland University of Technology. ↵

- Henry, E., & Wikaire, M. (2013). The Brown Book: Protocols for Working with Māori in Screen Production. Ngā Aho Whakaari Inc. https://www.nzfilm.co.nz/resources/brown-book ↵

- Out of respect for the language written by our ancestors, we have not inserted macrons, which are a relatively recent language-revitalisation tool. ↵

- Stokes, E. (1992). The treaty of Waitangi and the Waitangi tribunal: Maori claims in New Zealand. Applied Geography, 12(2), 176-191. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/0143-6228(92)90006-9 ↵

- Stenson, M. (2012). The Treaty: Every New Zealander's guide to the Treaty of Waitangi. Penguin Random House New Zealand Limited. ↵

- Orange, C. (2015). The Treaty of Waitangi. Bridget Williams Books. ↵

- Henare, M. (1998). Te tangata, te taonga, te hau: Maori concepts of property. Paper presented to the Conference on Property and the Constitution, Wellington for the Laws and Institutions in a Bicultural Society Research Project, Waikato University, 18 July. ↵

- Henare, M. (1995). Human labour as a commodity – a Maori ethical response. In Labour Employment and Work in New Zealand. Victoria University. ↵

- Best, E. (1924). The Maori as he was: a brief account of Maori life as it was in pre-European days. (No. 4). Owen, Government Printer. ↵

- Awatere, D. (1984). Māori sovereignty. Broadsheet. ↵

- Mataira, P. (2000). Nga kai arahi tuitui Māori: Māori entrepreneurship: The articulation of leadership and the dual constituency arrangements associated with Māori enterprise in a capitalist economy. Unpublished Doctoral Thesis, Massey University. ↵

- Ngāi Tahu. Nau mai, tauti mai. (2023). https://ngaitahu.iwi.nz/ ↵

- Tainui Group Holdings. (2023). Purpose. https://www.tgh.co.nz/ ↵

- Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu Group. (2022). Annual Report 2021-2022. https://ngaitahu.iwi.nz/assets/Documents/Te-Runanga-o-Ngai-Tahu-Annual-Report-2022.pdf ↵

- Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu. (n.d.). Ngāi Tahu 2025. https://ngaitahu.iwi.nz/assets/Documents/NgaiTahu-20251.pdf ↵

- Russell, C., Taonui, R., & Wild, S. (2012). The concept of taonga in Māori culture: Insights for accounting. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 25(6), 1025-1047. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/09513571211250233 ↵

- Whai Rawa. (2023). P¬¬ūrongo ā-tau 2022/23. https://www.ngatiwhatuaorakeiwhairawa.com/media/1876/j0449-nwo-whai-rawa-annual-report-2023-fa.pdf ↵

- See the Whai Rawa Unit Trust Statement of Investment Policy and Objectives (dated 31 October 2022) for a full list of excluded products, services, and industries. ↵

- Whai Rawa Unit Trust. (2022). Statement of investment policy and objectives. ↵

- Wakatū Incorporation. (2020). About Wakatū. https://www.wakatu.org/about-wakatu ↵

- The "Nelson Tenths" are named for the original 1840s sale agreement between the London-based New Zealand Company and the Māori landowners, promising one-tenth of settled land to be retained for Māori. However, most of the promised land was not kept for resident Iwi, and Wakatū Inc. lead the long-running legal fight for the Crown to remedy the historical contractual breach (see, e.g., Neal 2023a; Neal 2023b). Legally, it is not a Treaty Settlement due to the nature of the arrangement with the New Zealand Company. ↵

- Kono. (2022). About. https://www.kono.co.nz/our-values. ↵

- Brown, M. (2018, August 2018). Māori company plans for the future with 500-year plan. Stuff.co.nz. https://www.stuff.co.nz/business/105970245/mori-company-takes-the-long-view-on-their-business-goals ↵

- TAHITO. (2023). Statement of investment policy and objectives 2023. https://tahito.co.nz/sites/default/files/documents/TAHITO%20SIPO%2010%20August%202023.pdf ↵

- TAHITO. (n.d.). Indigenous investing. https://tahito.co.nz/indigenous-investing#investment-philosophy ↵

- Poyser, A., Scott, A., & Gilbert, A. (2021). Indigenous investments: Are they different? Lessons from Iwi. Australian Journal of Management, 46(2), 287-303. https://doi.org/10.1177/0312896220935571 ↵

canoe

genealogy

chiefs

elders

wisdom

extended family

community

tribe

traditional customs/values

spirit/power

treasure

family; relationships

stewardship/guardianship

spirituality

land

blessing