2 Challenges to Shareholder Primacy

Saphira Rekker

Chapter Overview

At the end of this chapter you will be able to:

- Identify the differences in the basic legal forms of business organisation and the implications for business purpose.

- Evaluate various business purpose theories.

- Apply the different business purpose theories to a case.

Introduction

In your own life, you will most likely spend money on things that you value. However, in a business, this can be a little bit different, as you will have to consider what others value. Not all businesses are the same in terms of legal structures and responsibilities. In this chapter, we will explore the common business structures that are in Australia, and discuss different views of what the role of the company is in society. This is particularly important when considering social and environmental factors in business decisions, which all businesses have to consider as they are a part of, and interact with, society. You will also learn how to apply different business purpose theories to a case.

Basic Legal Forms of Business

In Australia, there are four main legal forms of business:

- Sole trader (called sole proprietorship in the US)

- Partnership

- Corporation

- Trust.

The differences between these business forms are mostly surrounding their tax liabilities, asset protection, and ongoing administrative costs. Businesses may change their business structure over time. Many companies start as sole traders and progress to other structures as the business grows. The Australian Tax Office (ATO) has a video on choosing your business structure that explains the different structures in more detail.

Note that there are many different types of organisations, with different objectives, including not-for-profits and charities. Such organisations exist to achieve a social or environmental mission, but of course it is important for them to manage their finances effectively to maximise impact, and much of your traditional finance knowledge will be useful for these organisations. In the remainder of this chapter, we assume for-profit corporations when we talk about companies and corporations.

Sole Trader

Let's imagine that you would like to open a coffee shop. We will use this example throughout this chapter.

For a small coffee shop that you started with your own money, a sole trader may be the best option for your business. A business as a sole trader is extremely easy to set up; it takes you about an hour to apply online on the ATO website for an Australian Business Number (ABN) (note that you do need a separate bank account for the business!). It is also the least regulated, saving you a lot of paperwork, time and money compared to other business structures that are more regulated.

Whilst you get to keep all the profits if the firm makes money, you are subjected to unlimited liability. As the sole equity holder, this means that you are fully personally liable for any of the firm's debts, so if you go bankrupt and are unable to pay the debts, you may owe your creditors money until it is paid off in full or creditors may be able to seize your personal assets. Note that banks may be reluctant to lend you money in the first place and will often decide how much to lend based on how many personal assets you own.

Partnership

A partnership is a business that is owned by two or more people and is still relatively easy to start. A partnership has the advantage of having more capital available than a single person, but it may still be limited in raising any external capital. A general partnership consists of general partners only who all face unlimited liability just like a sole trader. However, in a limited partnership, there are still one or more general partners that have unlimited liability, but there are also one or more limited partners, who do not actively participate in the business and whose liability only extends to the amount they have put into the business.

Corporation

A corporation is a very unique business structure. It is an “incorporated” organisation, a separate legal entity, that is governed by law. It can sue and be sued, it can own assets and be in debt, very similar to a legal person, but born only on paper. A corporation is also the most complex business structure, requiring substantial paperwork and compliance costs over its life. In return, it gives many advantages and has become a much-preferred business structure in the last century.

A corporation enjoys the ability to raise capital more easily than other business structures because it is able to issue shares to the financial market (privately if a private company or publicly if it is a public company). Especially when publicly traded, transfer of membership is easy given that shares can be bought and sold on the stock exchange (or privately). It is attractive to invest in for members (shareholders) as they enjoy limited liability; the only money members can lose is the money they paid for the shares, as they are not liable for the firm’s debts in case of bankruptcy (and thus no-one can go after the member’s personal assets!). This limited liability of members also extends to any fraudulent, negligent or reckless acts that any directors or employees engage in. However, directors and employees are personally liable for any of those acts. Further benefits include that the life of a business is not bound to that of any of the members; its life does not have a limit.

Apart from increased costs, there are some disadvantages of incorporating a business. If you move from a sole trader or partnership to a corporation, and you are not the majority shareholder, then you may lose control of what will happen with the business. We will discuss the implications of this later in the chapter.

Test Your Knowledge

Joe and Annie have recently decided to start a business together. They have not formally registered their business structure, and they are currently operating as co-owners. Joe primarily manages the day-to-day operations of the business, while Annie provides financial support. They are unsure about the legal and financial implications of their business structure and are seeking clarification on which form of business organisation they are using by default.

Concept Check

What are the advantages and disadvantages of each of these possible business forms for StudyApp? (drag and drop each grey box to a relevant column).

We have learned the basics of three commonly occurring business structures - sole trader, partnership and corporation. In the next section, we are going to discuss different theories of business purpose.

Theories of Business Purpose

We have talked a little about how a business can be structured, but what is the purpose of a business in society? What should a business value?

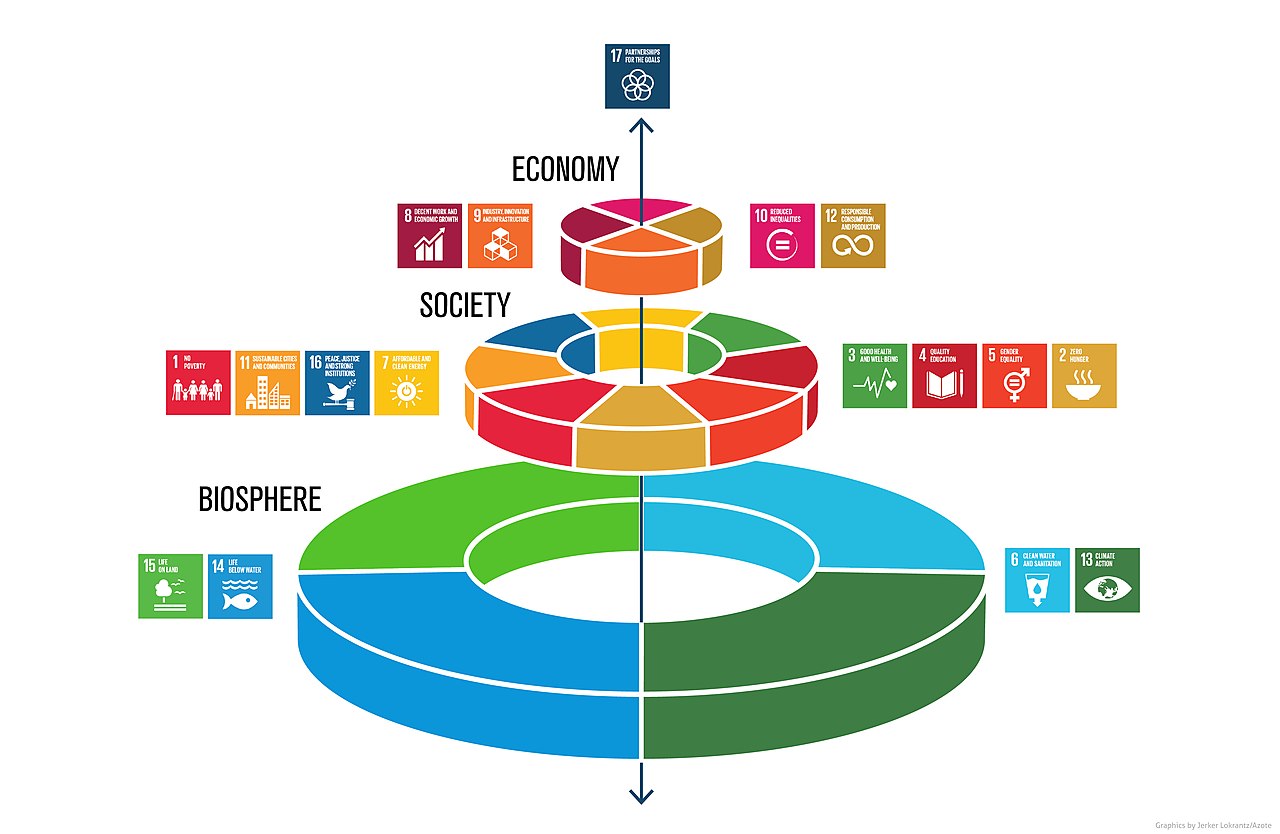

First, let's have a look at what you value yourself, using the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). The SDGs are a set of 17 goals, with 169 targets, that are "a blueprint to achieve a better and more sustainable future for all".[1]. It is in response to an urgent call for action by all nations, both developed and developing, to work together to end poverty whilst improving health, eduction, equality and economic growth, whilst tackling climate change and other environmental threats. All 193 of the world's countries have committed to these goals, that are to be achieved by 2030. Below are the 17 goals:

To simplify the goals, we can divide them into environmental (biosphere), social (society) and economic.

For societies and economies to thrive long term and be sustainable, we need a highly functioning natural environment and healthy, equitable social systems to support them. Unfortunately, many countries are falling behind on their goals. Visit the Sustainable Development Report for the most recent country rankings.

Polls

Poll 1

Poll 2

Sole Traders and Partnerships

As a sole trader, you own the business all by yourself. As a partnership, you own the company with your partners. In both those cases, you have direct control over what happens in the company and the consequences are yours as well. You make the decisions by yourself or with your partners. For example, you can choose how you treat your employees, and you'll probably realise that you have to create some value for them if you want to retain them. Do you give them part of the profits when you have had a good month? Or do you keep it to yourself?

Let's consider your coffee shop. You can decide whether you give a discount on customers bringing their own cups, if you sell fair-trade coffee only, etc. Let's say the cost of a "common” discount is $0.50 for customers using a own cup, but a disposable cup only costs you $0.05. Should you offer the "common" discount? From a purely financial perspective, you may say no, but the reality is that most coffee places now offer this discount. Some may argue that considering the environment (through reducing the billions of coffee cups ending up in landfill) is either "good business", as you enhance your reputation, remain competitive and your customers might be more loyal, whereas others do it simply because it is "the right thing to do".

The Corporation

To what extent should companies consider the social and environmental impacts of their business? How should these be balanced against financial performance? These questions have been long debated, some of the answers are set in law and regulation, others in culture, and can differ across and within countries.

The 20th century produced something unique, which was the rise of the corporation, a separate entity from both its owners and management, which for the first time allowed companies to have dispersed equity ownership.

Before companies started raising capital from the public, companies were closely controlled by those who owned them. However, when the industrial revolution started and production ramped up, owners of companies had to increasingly hire managers to help manage the company’s operations. And in the 20th century, when companies went to the public for finance more and more often, there started to be an increased separation between those that are shareholders of the company and those who manage the company.

Managers are often seen as employees (“agents”) of the company that are hired by the shareholders (“principals”). To make sure that the agents act in the best interest of principals, and not for example in their own self-interest, the shareholders elect a board of directors to oversee the company. Moreover, shareholders often receive voting rights with their shares, where they can vote on the board of directors and other important matters at the annual general meeting.

In most textbooks, you will often see the following argument: shareholders "own" the company (residual claimants of the firm) → management and directors have to do what the shareholders want → shareholders want maximum wealth (as a measure of value) = maximum share price; thus the role of the financial manager is to maximize the value of the shares (share price). This argument was mostly instigated by Milton Friedman (1970), the father of shareholder theory. His idea was further enhanced by Jensen and Meckling (1976) in their work the "Theory of the Firm"[2], one of the most cited and influential works in finance literature, which discusses the main challenge that needs to be addressed in corporate governance is that the managers and directors act to maximize shareholders’ wealth. This view is discussed in more detail next.

Shareholder Theory (Friedman, 1970)

Milton Friedman, a Nobel prize-winning economist, wrote an article in the New York Times in 1970 entitled “The Social Responsibility of Business”.[3] In this article, he writes about businessmen that believe that businesses may have a responsibility beyond just making a profit - a responsibility to achieve some “social goals”. He strongly disagrees with this and quotes from his book Capitalism and freedom (1962) in which he argues:

And

Thus, Friedman concludes that the one and only responsibility of a business is to increase profits for shareholders. Note, however, that he does not believe that this should occur at all costs; the actions to achieve these profits have to be legal and conform to ethical custom. His main concern about a business manager pursuing anything other than profits is that the manager is spending someone else's money:

Friedman was not against giving money to a charitable organisation or helping out friends, he just believed that if anyone wanted to give money to charity or anyone that this should be with their own money. A manager sponsoring the local ballet, soccer club or the Red Cross with corporate funds may be something the shareholders do not want to spend money on. Shareholders may want to spend the proceeds of the businesses’ money on other pursuits. Both shareholders and managers themselves are of course free to give money to charity as well, but their own money. Friedman also argued that if managers spent money on charitable organisations or any other “social” goal, the managers would be acting as a regulator, as they are effectively imposing a tax and deciding where the proceeds of the tax would go to, and this should be determined through a democratic process, not a corporate executive.

Concept Check

In September 2019 there were so-called “climate strikes” across the world to demand regulatory action on climate change. There were a large number of businesses that expressed their support and encouraged their employees to take the afternoon off (paid) to join the strike.

Let’s go back to your coffee shop for a little bit.

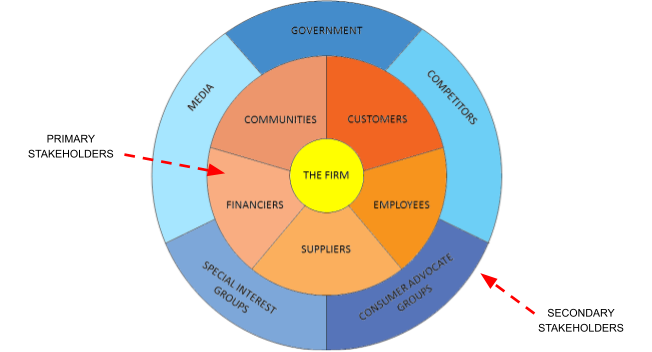

While running the business, you will be both impacted by, and impact, a number of entities in society. Your customers impact whether or not you can stay in business, and at the same time, your service and the quality of you coffee have an impact on the wellbeing of the customers. Your suppliers have an impact on the quality and availability of your coffee, whilst you also impact their ability to be in business. Entities that affect the firm, and/or are affected by the firm, are what we call stakeholders. In reality, stakeholders have an impact on the success of a business.

Shareholder theory does not deny this but rather proposes that stakeholders are a means to an end (maximising wealth for the shareholders, also called shareholder primacy). So for example, if wages can be cut to generate a profit, they should be cut. If dumping waste in a river is cheaper than treating it, the waste should be dumped in the river. If paying liability suits for a defective product is cheaper than making the product safe, then it is best to make the defective product and pay for the lawsuit. The following video shows a debate between Friedman and a student at Cornell University in 1978.

Milton Friedman on Self-Interest and the Profit Motive (YouTube, 6m56s):

Friedman proposes that perhaps the car company should have put a disclaimer on the product saying “this product is $13 cheaper and therefore has an increased chance of x% of exploding under y situation”. Do you think companies should do this? Do you think they do? Do you think people are really “free” if they do not have information on the possible impacts of products on individuals/society when buying a product? Who should be responsible for providing this information?

Enlightened Friedmanite

There is much criticism of Friedman’s view (shareholder primacy), particularly as it is often used to justify focusing on short-term company valuations. If managers are to focus on maximising shareholder wealth in the next year, does that mean they are maximising their wealth over the next 5 years? 10 years? 50 years? Is higher current wealth necessarily in the best interest of shareholders who may hold their investment for years or decades? “Enlightened” Friedmanites take a longer-term perspective. Is it in the best interests of shareholders to clear-cut a forest and maximise current production, without replanting it? Or to sustainably manage the forest resource so that it provides a moderate level of output for decades to come? This long-term perspective can lead to the same result as managing for stakeholders (discussed next), but there is a difference in motive.

Stakeholder Theory (Freeman, 1984)

One of the leading alternatives to shareholder theory is stakeholder theory, proposed by Edward Freeman in 1984.[7] Stakeholder theory asserts that a manager’s goal should not be to maximise shareholder wealth as a primary purpose, but rather to create value for all stakeholders. Freeman intentionally used the word “value” instead of “wealth,” as value includes (but is also broader than) financial outcomes. It includes human well-being, benefits from collaboration, etc.

Freeman[9] classifies five primary (most important) stakeholders and their stakes are as follows:

- Financiers (shareholders and debtholders) have a financial stake in the firm and expect a financial return from the firm

- Employees provide human capital to the firm and are impacted by the firm in terms of working conditions. Employees may also be decision-makers in the firm (e.g. if they are managers), or they can also be financiers (e.g. via employee stock options)

- Suppliers and customers have a stake in the firm in terms of exchanging products and services for resources (money)

- Communities grant firms the “right to operate” and can be impacted by the firm’s operations e.g. provision of local services or dumping hazardous waste.

There can also be secondary stakeholders, as shown in the diagram below:

There may be conflicting interests between groups of stakeholders and the manager’s job is not to trade-off these conflicts, but to work out a way to create value for all parties. Stakeholder theorists, therefore, argue that managing for stakeholders is simply good business practice. If all stakeholders are managed well this will result in a profitable, well-run firm.

Concept Check: What is happening in the real world?

The Business Roundtable is an organisation that consists of Chief Executive Officers (CEOs) of more than 181 major companies in the United States. The organisation has been issuing statements on the Purpose of the Corporation since 1978, and since 1987 it has defined the purpose of the corporation to be to serve shareholders first and foremost.

In August 2019, "the Business Roundtable"[10] changed its statement to:

We commit to:

- Delivering value to our customers. We will further the tradition of American companies leading the way in meeting or exceeding customer expectations.

- Dealing fairly and ethically with our suppliers. We are dedicated to serving as good partners to the other companies, large and small, that help us meet our missions.

- Supporting the communities in which we work. We respect the people in our communities and protect the environment by embracing sustainable practices across our businesses.

- Generating long-term value for shareholders, who provide the capital that allows companies to invest, grow and innovate. We are committed to transparency and effective engagement with shareholders.

- Each of our stakeholders is essential. We commit to delivering value to all of them, for the future success of our companies, our communities and our country.

Concept Check

The example above demonstrates that there is a change in business sentiment. CEOs are increasingly realising that creating long-term value for shareholders requires creating value for its stakeholders. Through innovative thinking many co-benefits can be created. In some regions like Europe, there is also increasing regulation on disclosure of companies' social and environmental impacts, so there is more information and transparency for people to make informed decisions.

Shareholder Value Myth (Stout, 2012)

Cornell Professor of Corporate Law, Lynn Stout wrote a book entitled The shareholder value myth[11] in which she discusses the history of the role of companies in society and several inaccuracies about shareholder theory. Watch the video below (for more info here is an article too).

The shareholder value myth | Lynn Stout, Cornell University (YouTube, 12m43s):

Concept Check

Shareholder Welfare not Wealth (Hart, 2017)

Lynn Stout's last point regarding shareholders having pro-social concerns is very similar to Oliver Hart's thesis below.

In the video below, Oliver Hart (winner of the 2016 Nobel Prize in economics) discusses shareholder theory and provides a new perspective on what the goal of the firm should be. In his paper with colleague Luigi Zingales, "Shareholders Should Maximize Shareholder Welfare not Market Value"[12], thet argues that firms should maximise the welfare of shareholders, which is much broader than wealth. Shareholders are all participants in society and have a range of social and environmental preferences. When a company engages in actions that maximize profits but create externalities that go against a shareholders’ ethical preferences, it is suboptimal to engage in these actions and then let the shareholders "mitigate" the externalities with their own money. Firms should therefore actively seek shareholders' preferences and values, and act consistently with those. Watch the video below

Shareholders care about more than just profits (YouTube, 4m12s)

Case Study: Gun Control

Hart & Zingales uses the example of Dick’s Sporting Goods, which changed its policy on gun control.

Dick's Sporting Goods could generate money by selling assault rifles. Friedman would have argued that, if it is a profitable strategy to sell high-powered guns, then the company should do so, pay shareholders the extra dividend, and then the shareholders could decide individually to support gun control organisations. However, shareholders spending their own money to "reverse" the actions of the company would be very inefficient and suboptimal for the shareholders.

Hart argues that it is more efficient for the company to refrain from selling assault rifles in the first place. Shareholders are humans, who have pro-social concerns, and it is assumed that if someone is not only interested in the bottom line, they would prefer to invest in companies that are also interested in issues beyond the bottom line. Hart argues that if a CEO and managers want to show loyalty to their shareholders, their individual concerns should be taken into consideration.

In other words, instead of making money at the expense of all, the pro-social concerns of shareholders should be accounted for when building a strategy.

Exercise: Child Labour

Many companies in the fashion industry operate in developing countries, where labour is cheap and regulations on working conditions and education possibilities are poor. Whilst most of these countries do not legally allow child labour, regulations are not often enforced, as the low wages make it difficult for parents to miss out on the extra income their children can bring in. The CEO of "CheapApparel", a company known for its cheap apparel, says "Our duty is to maximize value for shareholders, this means we have to minimize our costs, and after all, our consumers want the cheapest products." He further says that "without us, our employees would not have any income at all." He does say that he cares about education a lot, and that he personally donates 5% of his income to education initiatives in developing countries. He argues that it would be wrong to donate money with the companies' funds, reasoning that this is the money that belongs to shareholders, who if they wanted to, could donate this themselves.

Answer:

- Hart would assert that many shareholders do care about ethical labour practices and would prefer their investments not to contribute to exploitative practices, such as child labour and poor working conditions.

- Hart might challenge the CEO's claim that minimising costs and providing the cheapest products is the only duty to shareholders. He would likely argue that a company's responsibility includes ensuring that its operations do not harm workers and communities.

- Hart might argue that by improving labour conditions and investing in education, CheapApparel could create long-term value and goodwill, which are also in shareholders' best interests.

- Hart would also probably contend that the CEO’s personal donations, while commendable, do not absolve the company from its responsibilities. Corporate actions reflect on the company as a whole and have a more substantial impact than individual contributions.

Discussion: Short Case Study - Merck

Exercise

Assume you were Merck's CEO and you were aware that Vioxx had possible dangerous side effects:

Lawsuits for dangerous side effect and deaths = $ -5 billion

Net revenue from selling Vioxx = $ 10 billion

Answer:

Since the question was based on what you would do, there is no “correct” response. However, a sample solution is provided above, and a response which included the point below would have been on the right track.

- While the initial financial gain from Vioxx might align with Friedman's (1970) shareholder theory, the long-term repercussions of this approach highlights the importance of considering stakeholder interests and ethical responsibilities as emphasised by Freeman (1984), Stout (2012), and Hart (2017). Moving forward, Merck should prioritise the welfare of all stakeholders to ensure sustainable success and avoid similar pitfalls.

This chapter is adapted from "What is Financial Management" in Introduction to financial management: A contemporary approach by Saphira Rekker (forthcoming) under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

Review Questions

Complete the chapter review questions below to test your knowledge.

- United Nations. (n.d.). Sustainable Development Goals. https://sdgs.un.org/goals ↵

- Jensen, M. C., & Meckling, W. H. (1976). Theory of the firm: Managerial behavior, agency costs and ownership structure. Journal of Financial Economics, 3(4), 305-360. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-405X(76)90026-X ↵

- Friedman, M. (1970, September 13). The social responsibility of business is to increase its profits. The New York Times. SM12. ↵

- Friedman, M. (1962). Capitalism and freedom. University of Chicago Press. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Freeman, R. E. (1984). Strategic management : A stakeholder approach. Pitman. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Business Roundtable. (2019, August 19). Business roundtable redefines the purpose of a corporation to promote ‘an economy that serves all Americans’. https://www.businessroundtable.org/business-roundtable-redefines-the-purpose-of-a-corporation-to-promote-an-economy-that-serves-all-americans ↵

- Stout, L. A. (2012). The shareholder value myth. Berrett-Koehler Publishers. https://scholarship.law.cornell.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2311&context=facpub ↵

- Hart, O., & Zingales, L. (2017). Shareholders should maximize shareholder welfare not market value. Journal of Law, Finance, and Accounting, 2, 247 -274. https://scholar.harvard.edu/files/hart/files/108.00000022-hart-vol2no2-jlfa-0022_002.pdf ↵