2.4 Memory and Information-Processing

Negotiators, mediators, facilitators, as well as parties who are negotiating for themselves have to handle complex issues and multiple pieces of information at once during a conflict resolution process. This includes remembering events from the past and considering new information. These tasks require all types of memory, including sensory, short-term, and long-term memory. We will now have a look at how these different types of memories function. But first, as a fun introduction to the topic of memory, you may want to watch the following Crash Course video [9:55]:

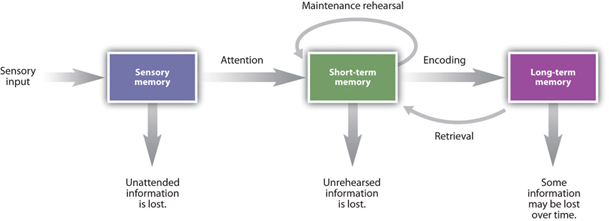

We will now consider various types of memory functions in more detail. The sensory memory holds incoming information, but only for a few seconds (Gluck et al., 2020).

As you can see in the above image, our attention selects which information is passed on from the sensory to the short-term memory. Note how attention, which we discussed in more detail in the previous topic, affects what information gets passed on to our memory. As this example shows, all our cognitions and mental processes are somehow interlinked and connected.

Short-Term Memory

The short-term memory includes the so-called “working memory”, which manages control processes such as rehearsal, encoding, decisions and retrieval strategies. Research using the digit-span test (click the link to try this test out yourself) has shown that our short-term memory can hold on average between five to nine items at the same time. You may have heard before that the human mind can pay attention to an average number of seven at the same time (e.g. George Miller’s “magical number 7”).

To retain information, the short-term memory uses several strategies, including “coding” and “chunking”. Coding refers to how information is represented, and there are various types of coding. For example, remembering the sound of your mother’s voice is “auditory coding”, and remembering what your mother looks like is “visual coding”. Chunking, on the other hand, involves combining smaller units into larger, more meaningful units (e.g., instead of trying to memorise the sequence of the numbers 1, 9, 7, and 9 I might “chunk” them as 1979, the year when I was born. Or, if you must remember a suite of words, you could create a short story containing all the words that you need to remember). This process of chunking is relevant to the management of conflict. Conflict management practitioners supporting negotiations between two conflict parties are frequently trained to chunk information relating to complex issues and options when making offers to the other party. You will shortly be referred to a reading by Alexander et al., (2015), pp. 159-162: ‘Making the most of memory’ to explore how knowledge about memory may help prepare for and conduct a negotiation. Before we refer you to the reading, we will consider the working memory in some more detail.

Baddeley’s Working Memory Model

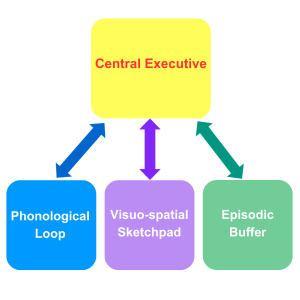

To better understand working memory, Alan Baddeley developed the “working memory model”. According to Baddeley, the working memory is a system with several parts controlling the information being processed. Baddeley initially identified three main components, with a fourth (the episodic buffer) added some 25 years after its inception:

- The phonological loop, which holds verbal and auditory information

- The visuospatial sketch pad, which holds visual and spatial information

- The central executive, which works with information and is responsible for updating and re-organising working memory to balance multiple goals and switch attention between different activities

- The episodic buffer was added to explain the temporary integration of information gathered from the phonological loop, visuospatial sketchpad, and long-term memory. Its addition to the original model allowed a clearer connection to be made between working memory and long-term memory. This component is controlled by the central executive and transfers information into and out of the long-term memory.

To learn more about the working memory and its components, watch the following 7-minute video: Working Memory (Test + Examples):

As noted in the video, it is assumed that each component of the working memory has a limited capacity and is largely independent of the others. The visual sketch pad is not affected by the phonological loop and vice versa. We can draw some conclusions for conflict management from knowledge about the working memory. For example, when parties need to process a lot of information at once, such as in a multi-issue, multiparty negotiation, it may be advised to present some information visually, rather than verbally to relieve the phonological loop. For example, a mediator may draw the outline of houses, fences and trees concerned in a neighbourhood dispute on a whiteboard.

Key Reading

There are many ways we can get information from the working memory into our long-term memory. If you need to remember a phone number to use in the future, you are likely to engage in the processes of encoding, storing and retrieval of information. Encoding happens when you initially memorise the number. Storing refers to maintaining the memory of the number over time, e.g., by rehearsing it. The process of retrieving the number when you finally need to use it is known as ‘retrieval’.

We will look at the topic of memory again in the next chapter when we consider the impact of emotions on cognitive processes, including memory.

Long-Term Memory and Priming

To conclude the cognition of memory, we will now have a brief look at the long-term memory, with special attention paid to a phenomenon called “priming”. The long-term memory can be categorised as explicit and implicit memory (Goldstein, 2019; Gluck et al., 2020). The explicit memory (also called declarative memory) comprises the semantic memory (memory of facts and general knowledge) and the episodic memory (memory of personal experiences) (Goldstein, 2019; Gluck et al., 2020). The explicit memory “consists of memory of which a person is aware; you know that you know the information” (Gluck et al., 2020, p. 280). The implicit memory, on the other hand, is “memory that occurs without the learner’s awareness” (Gluck et al., 2020, p. 280). Priming is a phenomenon associated with our implicit memory (Goldstein, 2019), and is, therefore, a process that happens unconsciously.

Priming

Priming is a psychological phenomenon where exposure to a stimulus influences how we respond to subsequent stimuli, and how we perceive and interpret new information. As defined by Gluck et al. (2020), priming is “a phenomenon in which prior exposure to a stimulus can improve the ability to recognize that stimulus later” (p. 88). Similarly, Kassin et al. (2020) describe priming as “the tendency for frequently or recently used concepts to come to mind easily and influence the way we interpret new information” (p. 118). In essence, priming makes certain concepts or ideas feel familiar, even if we aren’t consciously aware of the exposure.

For example, research has shown that if we’re subtly exposed to specific words or images, we may later be more likely to recognise or choose something related to those stimuli (Gluck et al., 2020; Goldstein, 2019; Kassin et al., 2020).

The impact of priming on social behaviour

Exposure to a stimulus can also lead people to behave in a particular way without their awareness, in particular when the stimulus was presented subconsciously (Kassin et al., 2020). The impact of priming has been demonstrated in research, including in a provocative study by Bargh, Chen and Burrows (1996).

For example, in experiment 1 of the study, participants were primed to activate either the constructs “rudeness” or “politeness” and were then placed in a situation where they had to either wait or interrupt the experimenter to seek some information. The research found that participants whose concept of rudeness was primed interrupted their experimenter more quickly and frequently than did participants primed with polite-related stimuli.

In experiment 2, participants were primed with words that activated elderly stereotypes. The study found that participants for whom an elderly stereotype was primed walked more slowly down the hallway when leaving the experiment than did control participants, consistent with the content of that stereotype.

Extention:

For further information about these experiments, refer to Gluck et al. (2020). The authors discuss the implications of this automatic behaviour priming effect for self-fulfilling prophecies, a phenomenon that is frequently noted in the conflict management literature.

To learn about a similar study on how priming may affect the behaviour of individuals, please watch the following 5-minute video.

How does priming relate to conflict management?

We are considering priming here because this phenomenon has been discussed in some articles that focus on conflict management.

Priming in mediation

Weitz (2011), in his article The brains behind mediation: Reflections on neuroscience, conflict resolution and decision-making discusses how priming can influence the mediation process. The author suggests that by using words like “listen to, hearing each other, dialogue, options, future” mediators may be able to “prime” parties for collaboration rather than competition (Weitz, 2011, p. 478).

Similarly, Hoffman and Wolman (2013) in their article The psychology of mediation note that the mediator’s initial description of the mediation process is the most powerful form of priming in mediation. Based on priming studies (which the authors mention but don’t specifically list), they suggest that mediators may wish to include expressions such as “being ‘flexible’ and ‘open-minded,’ the goal of reaching ‘a fair and reasonable resolution,’ and the need for ‘creativity’ and ‘thinking outside the box’” in their opening statements (p. 3).

Beyond the mediator’s opening statement, Sourdin and Hioe (2016), in their article Mediation and psychological priming, discuss other opportunities for priming during the mediation process. They suggest that mediators can “strategically moderate the environment” to foster a positive atmosphere and encourage successful outcomes (p. 79). Such moderation can be achieved, for example, by carefully selecting and setting up the physical location of the mediation, including considerations of room colour, temperature, and the provision of food and water.

Carruthers (2017), in her article on The impact of psychological priming in the context of commercial law mediation, explores factors such as the physical appearance of the mediator and legal representatives, the choice of venue, language use, and the influence of stress and references to money. She concludes that mediators and legal practitioners should avoid overt priming cues related to strength, power, and money to improve the positions of both parties in commercial mediation.

Key Reading

How priming can affect perception

If you watched the Crash Course video Perceiving is Believing, you may remember that you were primed to see either a rabbit or a duck, depending on the question asked (bird or mammal). People are particularly likely to rely on the priming effect when new information is ambiguous. This is because we rely more on top-down processing than bottom-up processing when we are confronted with an ambiguous stimulus.

Bottom-up processing begins with our receptors, which take in sensory information and then send signals to our brain. Our brain processes these signals and constructs a perception based on the signals. When our perception depends on more than the stimulation of our receptors – and this is frequently the case when information is ambiguous – we speak about top-down processing. During top-down processing, we interpret incoming information according to our prior experiences and knowledge. This process is frequently referred to as concept or schema-driven. As we learned earlier, when we have been primed, frequently or recently used concepts come to mind more easily and influence the way we interpret new information.

Kendra Cherry, the author of Priming in psychology, discusses how the priming effect influences what people hear when confronted with ambiguous auditory information, referring to the 2018 Yanny/Laurel viral phenomenon.

As an example of visual perception, Feldman Barrett (2017) explains how priming can significantly influence our visual perception of others’ emotions. She emphasises that facial expressions are often much more ambiguous than many popular readings suggest, which would make us particularly susceptible to the effects of priming. For instance, if we’re told a person in a photo is screaming in anger, we are more likely to see anger in their expression, even if this is inaccurate.

The person might actually be celebrating something positive, such as winning an important tennis match, potentially involving a whole mix of (positive) emotions, but the priming narrows our interpretation. With contextual information provided, we are likely to interpret the facial configuration more accurately than when taken out of context.

How does the priming effect and perception relate to conflict management?

A mediator might misinterpret facial configurations of parties in a mediation, interpreting emotions like anger, based on preconceived ideas of how people may “express” that emotion on their face, or influenced by comments made by the other mediation party. Knowing about priming can sensitise us to potential misinterpretations of emotions, and encourages us to use multiple cues and information to more accurately perceive parties’ emotions. We discuss the topic of facial “expressions” in more detail in the next chapter. These cues and the topic of emotions in conflict are also discussed in much more detail in Sam Hardy’s course on Working with Emotions in Conflict.

Priming to improve inter-group relationships

Recent research by Capozza, Falvo and Bernardo (2022) examined whether activating a sense of attachment security can reduce the tendency to dehumanise “outgroups” – these are groups to which an individual does not feel connected or identify with (Kassin et al., 2020, p. 144). Two studies were conducted:

- the first primed attachment security by using images of close relationships and measured humanisation of the homeless

- the second asked participants to recall a warm, safe interaction and measured humanisation of the Roma.

Both studies found that attachment security led to greater humanisation of the outgroups, with the second study showing that increased empathy played a key role in this effect. The research suggests that intergroup relations can be improved by fostering a sense of security. These findings suggest that fostering a sense of security can enhance intergroup relations, which has implications for intergroup conflicts. The successful use of priming to boost feelings of security highlights the importance of applying cognitive psychology to conflict management.

The calming effect

Capozza, Falvo and Bernardo, in their article, discuss several further positive effects of security priming, many of which are relevant to conflict and conflict management/resolution. For example, they emphasise the calming effect of security priming, noting that “even a momentary sense of security can shift the attention from one’s needs to others’ needs…” (p.3).

Conflict management processes often aim to help individuals in conflict consider the needs and concerns of others. Understanding the calming effect of security priming and its ability to foster perspective-taking may provide conflict management practitioners with additional strategies to support their clients. Such strategies could consider aspects like:

- The choice of physical setting for a mediation or coaching session (or other conflict management process).

- The language used by the practitioner, such as during the mediator’s opening statement.

- The types of questions the practitioner asks throughout the process.

Remaining questions and considerations

As we have seen in this topic, research suggests that there are multiple opportunities to prime parties during a conflict management process, such as mediation, as discussed in the sources mentioned throughout this blog. However, many questions remain, such as how much control a practitioner truly has over priming in a conflict management process Additionally, practitioners should consider the ethical implications, including the potential for manipulation, when applying priming techniques to their practice.

Extension:

If you are interested in priming and want to learn more about some specific examples and types of priming, you may also want to read this “easy to digest” description of priming.

Reflection Activity

You may now wish to spend 10 minutes considering how what you have just learned about memory may help you understand and/or support people in conflict. For example, you might want to note some key learnings from the readings by Alexander et al. (2015) and Weitz (2011). You might also want to think about how the phenomenon of priming may relate to people’s conflict experiences and what it may mean for the process of conflict resolution.