Chapter 8: Using Conceptual PlayWorlds to build Wellbeing

Kelly-Ann Allen

Chapter Goals

By reading and exploring the content of this chapter, you will learn:

- the importance of wellbeing in early childhood

- determinants of wellbeing in early childhood and the role of creativity, imagination, and play

- how to use Conceptual PlayWorlds to build wellbeing.

Introduction – Jumping into the Imaginary Situation

In this chapter, you will be working again with Charlotte, our student teacher, and Yuwen our experienced teacher, to explore the concept of wellbeing. They are co-teaching in a primary school this time, but another problem has arisen.

Charlotte has been reading the newspaper and found an alarming statistic, ‘Around 13.6% of children aged 4–11 are experiencing a mental health disorder’. She is puzzled and perplexed. How can this statistic be so high? She needs your help once again.

In this chapter, you will explore Charlotte’s latest problem around how she can better prepare herself to build the wellbeing of the students she works with in a way that responds to the increasing number of young children identified as having mental health problems. Your role is to work through a range of solutions to help Charlotte and her mentor, Yuwen, as they plan and implement a Conceptual PlayWorld to build wellbeing.

Don’t forget to record your thoughts in your personalised Fleer’sConceptual PlayWorld thinking book.

However, before you launch into understanding how Conceptual PlayWorlds can be used to build wellbeing, read Charlotte’s perspective and find out why she is so alarmed about the rising rates of mental health in young children.

Charlotte’s Perspective – Mental Health Problems are on the Rise and Building Wellbeing is a Proactive Solution

Figure 8.1.

Charlotte is shocked so many children struggle with mental health problems

Amid the bustle of the primary school where Charlotte now works, a statistic confronts her during a break in the staff room: ‘Around 13.6% of children aged 4–11 are experiencing a mental health disorder’. The numbers leap off the page of the newspaper, leaving her shocked. This new information gnaws at her all day. How could such a large proportion of young children be grappling with mental health disorders? She finds herself looking for guidance.

In this quest, she turns to her trusted mentor, Yuwen. Together, they ponder over how Conceptual PlayWorlds – could be used to foster wellbeing proactively and preventively. It feels like a great approach, but there’s a hitch.

Charlotte is a teacher, not a psychologist. She is willing and eager to make a difference. But a little voice inside her head whispers some self-doubt. She questions if she’s equipped or prepared to address mental health and wellbeing in students. She feels daunted but decides to tackle this challenge head-on while remembering, that she isn’t alone – with YOU and Yuwen right beside her.

Practice reflection 8.1: What do you think Charlotte’s most significant barrier is to implementing Conceptual PlayWorlds for Wellbeing? Record your thoughts in your personalised Fleer’sConceptual PlayWorld thinking book. Note Charlotte’s thinking and perceived preparation.

Diving into the Research

What is Wellbeing?

In education research and practice, the debate over whether it should be ‘wellbeing’ or ‘well-being’ – is only the tip of the iceberg when it comes to the complexity of this construct and how extensively it is debated, theorised, conceptualised, and operationalised in the literature. It is no surprise, therefore, that defining wellbeing can get pretty complicated. For the purpose of this chapter, the concept of wellbeing, is best described using Professor Martin Seligman’s weather metaphor (Seligman, 2011). Seligman, Director of the Penn Positive Psychology Center and Zellerbach Family Professor of Psychology in the Penn Department of Psychology, is a pioneering psychologist in positive psychology. He suggests that wellbeing is akin to the weather – an ever-changing, dynamic, multifaceted concept in a constant state of change – much like a child’s perceived wellbeing. However, like the weather is an umbrella term for a range of elements, such as temperature, rain, wind, UV rating, etc., wellbeing involves various domains such as happiness, coping, gratitude, grit, optimism, hope and physical health. In the same way that it is nearly impossible to capture the complexity of the weather with a single reading, it is also hard to measure a child’s wellbeing based on just a single score. This is because wellbeing is multifaceted and complex and what influences wellbeing can be unique and different for each child.

Figure 8.2.

Wellbeing and the weather

When working with younger children on concepts concerned with wellbeing, one important consideration is how they understand what this term means. Waters et al. (2022) investigated how five and six-year-olds understand and foster their wellbeing through a ‘draw and write’ methodology designed for young participants. This approach required children to illustrate their responses to a question about wellbeing and then explain their drawings. The results indicated that children at this age could understand and comprehend the concept of wellbeing and identify a range of practical strategies that built their wellbeing, like listening to music, receiving a hug, eating a lollipop and playing. These findings were informative in highlighting that young children are active participants in their own wellbeing and not merely passive recipients.

Figure 8.3.

Happiness

Research reading 8.1: Waters, L., Dussert, D., & Loton, D. (2022). How Do Young Children Understand and Action their Own Well-Being? Positive Psychology, Student Voice, and Well-Being Literacy in Early Childhood. International Journal of Applied Positive Psychology, 7(1), 91–117. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41042-021-00056-w

The Importance of Wellbeing in Early Childhood

Despite the well-documented importance of wellbeing for children in the early years of schooling for cognitive development, friendships and resilience (Bakken et al., 2017; Shoshani & Slone, 2017) and particularly in terms of long-term outcomes in adulthood related to future mental health, employment and general life satisfaction (Layard et al., 2014; Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development [OECD], 2020; Schoon et al., 2015), there is proportionately less information for educators on how they can foster wellbeing in early childhood compared to that available for older children and adolescents. Creativity, imagination and play allow young children to explore wellbeing concepts, while also potentially contributing to their wellbeing. Important evidence for this emerges from the research that shows engagement in creativity, play and imagination can contribute to wellbeing in childhood (Bungay & Vella-Burrows, 2013; Howard & McInnes, 2013; Lee et al., 2020; Silvey et al., 2004). This may be because these factors allow children to express themselves, explore their feelings, interact with their peers, solve problems and develop skills such as coping, all of which are vital elements of wellbeing. By integrating wellbeing concepts within creative and imaginative play, educators can create engaging, student-driven and age-appropriate learning experiences. This allows children to understand complex concepts of wellbeing in a way that is relevant to them. Therefore, play-based approaches like Fleer’s Conceptual PlayWorlds for Wellbeing have immense potential to teach children about wellbeing and related concepts. Conceptual PlayWorld provides a framework for educators to teach wellbeing. Educators who do not require specialised qualifications or training. In fact, everything you need to know to deliver a Conceptual PlayWorld is in this book!

Practice reflection 8.2: Now that you understand the importance of wellbeing for young children, can you help Charlotte? How would you help her feel more equipped to use Conceptual PlayWorlds to build wellbeing? What could have stopped her despite being alarmed by rising rates of mental illness? Record your answers in your Fleer’s Conceptual Playworld thinking book.

A Conceptual PlayWorld for Wellbeing

Conceptual PlayWorlds that build wellbeing share similarities with other playworlds in their design and implementation. However, they emphasise building in problem scenarios, discussion points, psychoeducational opportunities, and social and emotional learning opportunities that contribute to young children’s wellbeing. Both playworlds are rooted in constructing immersive, engaging, narrative-driven environments that allow children to explore certain concepts and ideas through play. Playworlds encourage children to engage in imaginative scenarios, problem-solving, and social interactions, providing opportunities for wellbeing literacy.

When Conceptual PlayWorlds are designed specifically for wellbeing, they build in elements that directly support the competencies, skills, opportunities, attributions and opportunities that help build wellbeing and related concepts. Activities in these playworlds may be crafted to help children identify and express their emotions, manage conflicts, build relationships and cope with challenges. The stories and narratives chosen can depict characters dealing with emotions or adversity (however minor), and the discussions and reflections can focus on learning social and emotional skills.

In contrast, while other playworlds might incidentally contribute to children’s wellbeing through engagement and enjoyment, they may not explicitly focus on building specific social and emotional skills or coping mechanisms. The primary focus of other playworlds may be on other concepts like mathematics (see Chapter 6) or language and literacy (see Chapter 7). Therefore, the main difference lies not in the structure of the playworlds but in the objectives, aims, and purpose as well as the specific experiences that aimed to be fostered.

The model for building Conceptual PlayWorlds for Wellbeing follows the same model as a typical playworld and is presented in Figure 8.4. It involves:

- Choosing a story;

- Planning a Conceptual PlayWorld for wellbeing;

- Planning how to jump into the story;

- Creating an authentic wellbeing problem; and

- Being a play partner. Considerations should be made as to how the learning objectives of the Conceptual PlayWorld for wellbeing can be sustained for the children.

Your role is to help Charlotte as she solves the challenge of planning and implementing a Conceptual PlayWorld to build wellbeing for the first time.

Figure 8.4.

Conceptual PlayWorlds for Wellbeing.

Planning a Conceptual PlayWorld for Building Wellbeing – Evidence Informed Model

Getting Prepared

Charlotte took a deep dive into the research on wellbeing and spent an hour or so reading the research. This helped her understand a few things:

- Many teachers feel under equipped when it comes to teaching or even support the wellbeing of students (Mazzer & Rickwood, 2015; Shelemy et al., 2019). There are some teachers that feel this is not their role (Graham et al., 2011) while other teachers feel that their courses did not adequately prepare them (Reinke et al., 2011). Charlotte felt relieved she was not alone, but also thankful that the textbook her university set as a reading detailed enough information on how to build wellbeing in young children to give her the confidence to go further with her professional development.

- That proactive and preventive approaches to wellbeing are considered world-standard best-practices in addressing mental health problems in children and adolescence. Charlotte felt relieved to learn this and this provided her with the motivation to know she was on the right path.

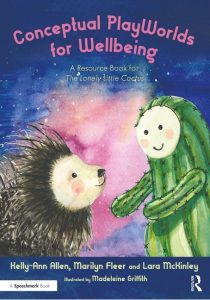

- One resource that exist on how to use Conceptual PlayWorlds for Wellbeing is:

-

- Allen, K.A., Fleer, M., & McKinley, L. (2023). Conceptual playworlds for wellbeing: A practical resource for the lonely little cactus. Routledge.

- A companion to picture story book, The Lonely Little Cactus: A Story About Friendship, Coping and Belonging. The resource utilises the Conceptual PlayWorlds model by Professor Marilyn Fleer and applies it to wellbeing. It’s designed to aid children between the ages of four and eight to tackle problems and comprehend wellbeing concepts via play.

- The guide works in tandem with The Lonely Little Cactus, which follows a lonesome desert cactus. It provides teachers and caregivers with richly illustrated scenarios and 20 distinct activities, enabling children to grasp wellbeing ideas through experiential learning. This resource directs users through various wellbeing activities, such as recognising emotions, developing coping mechanisms, cultivating friendships, fostering positive feelings, learning relaxation strategies, and promoting belonging and inclusion.

Figure 8.5.

The cover of Conceptual PlayWorlds for Wellbeing

Charlotte also discovered there is an endless number of picture story books that are perfect for developing into Conceptual PlayWorlds for wellbeing. Searching online she found resources that specifically listed books about wellbeing concepts like happiness, friendships, togetherness and belongingness.

You will find a planning proforma for Conceptual PlayWorlds for Wellbeing in your Fleer’s Conceptual PlayWorld thinking book and a generic proforma of a Conceptual PlayWorld in Appendix B. This is the planning framework that Yuwen introduced to Charlotte in their debrief in Chapter 1.

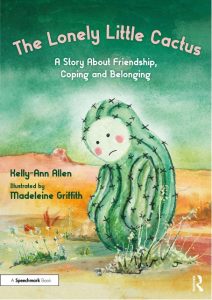

1. Choosing a Story

Charlotte spent a great deal of time and thought in selecting a book, The Lonely Little Cactus: A Story About Friendship, Coping and Belonging. The book is targeted at 4 to 8-year-olds and tells the tale of a solitary cactus in the desert. Throughout the story, the cactus interacts with various desert inhabitants and learns how to navigate its feelings of loneliness. This book underlines that feelings of loneliness are universal and can be dealt with effectively. It introduces children to different coping mechanisms and encourages them to discover what works best for them. The book serves as a tool for teachers, support staff, mental health professionals, and parents in guiding children to comprehend and manage their emotions and build well-being in young children.

Yuwen was impressed, not only at Charlotte’s planning but also by her willingness to engage in an area she felt less comfortable with. She said, ‘Charlotte, I can see your knowledge in this area has vastly improved. Your self-directed learning will be of great value to your professional development and your students’.

Charlotte had reframed her worries about feeling unequipped to feeling inquisitive and ready to take on the challenge of building wellbeing in her students!

Figure 8.6.

The cover of The Lonely Little Cactus: A Story About Friendship, Coping and Belonging

Practice reflection 8.3: In your Fleer’s Conceptual PlayWorld thinking book think about how you might apply a Conceptual PlayWorld model to build wellbeing. What would be different from other Conceptual PlayWorlds? What would be the same? Identify some pedagogical characteristics that you are curious about and start a discussion about it in our private Facebook for Conceptual PlayWorlds.

Research reading 1.2: You will find ideas about how to design interesting spaces for a Conceptual PlayWorld for wellbeing in Chapter 1 or Allen, K.A., Fleer, M., & McKinley, L. (2023). Conceptual playworlds for wellbeing: A practical resource for the lonely little cactus. Routledge. https://www.routledge.com/Conceptual-PlayWorlds-for-Wellbeing-A-Resource-Book-for-the-Lonely-Little/Allen-Fleer-McKinley/p/book/9781032073651

Charlotte shared her chosen book with Yuwen, who agreed with Charlotte that The Lonely Little Cactus had useful components to teach wellbeing. The Lonely Little Cactus engages in various strategies to build wellbeing, but also introduces a variety of characters along the way. The Little Cactus faces problems and challenges, and the book provides drama and suspense that make it easy to work with for building a Conceptual PlayWorld. Yuwen suggests to Charlotte that, on one hand, the book has important psychoeducational components in terms of teaching coping strategies; and on the other hand, it has important features to adapt to a Conceptual PlayWorld. Charlotte feels pleased that she has selected a great book!

Practice reflection 8.4: Find another children’s book you believe could be a book readily adopted into a Conceptual PlayWorld activity to build wellbeing. Record your ideas in your Fleer’s Conceptual PlayWorld thinking book, where you will find your proforma for Conceptual PlayWolrds for Wellbeing. Use the proforma to start to build your own playworld for wellbeing.

2. Planning a Conceptual PlayWorld Space

Yuwen asked Charlotte where she will design her Conceptual PlayWorld space. ‘Easy’, Charlotte says, ‘the desert!’.

Yewen reminds Charlotte that not all playworlds need to take place in the same setting as the book, but then asks: ‘How will you transform a playground into a desert landscape, and how will it promote wellbeing among primary school children?’

Charlotte explained her vision: ‘I see the playground as a blank canvas. To transform it into a desert, I will use sand, fabric, and cardboard to create dunes and cacti. We will have designated areas such as a ‘sand dune’ and a ‘campground’. These areas will provide different opportunities outlined in the play scenario.’

Figure 8.7.

Charlotte imagines the playground as a desert

3. Planning How to Jump into the Story

Yuwen reminded Charlotte to think about how she planned to enter the Conceptual PlayWorld with the children. Charlotte planned to take the class to the playground for the activity. In the playground was a traditional climbing frame, but for the purpose of the playworld, Charlotte explained to Yuwen it would become a magical mythical time portal that the children could walk through and step straight into the hot, dry, dusty desert where The Lonely Little Cactus takes place.

Practice reflection 8.5: How would you design the imaginary space for the book you have selected? Record your answers in your Fleer’s Conceptual Playworld thinking book.

Yuwen enjoys Charlotte’s idea and reinforces to her the importance of planning the entrance and exit. But Yuwen asked, ‘What role will the children play?’

Charlotte had forgotten to think of that! Yuwen suggested that the children could play desert dwellers and take on roles of animals commonly found in the desert, like small desert frogs or characters in the story, such as the porcupine and the porcupine’s friends.

Charlotte loved that idea. She thought she could play the role of the Little Cactus in the upper position and the children could play the role of porcupines in the lower position.

Practice reflection 8.6: Brainstorm a range of entry and exit routines for the book of your choosing. Record your ideas on your Conceptual PlayWorlds for Wellbeing proforma.

4. Creating an Authentic Wellbeing Problem

Yuwen asked to see Charlotte’s planning proforma. She asked, ‘What authentic problem could they solve together?’

Charlotte had clearly given this much thought! She had conceptualised the playworld for building wellbeing to extend the story of The Lonely Little Cactus. The playworld was a great opportunity for The Lonely Little Cactus, with the help of the porcupines, to help solve other challenges that might emerge. In The Lonely Little Cactus, the cactus had feelings like anger, worry and sadness because he felt lonely. Loneliness can affect our wellbeing, but all children (and all people in fact!) face other worries or stresses. In her research on coping (Frydenberg et al., 2014), Erica Frydenberg tells us that some of the biggest worries faced by children (3–6 years) include:

- uncertainty in new situations

- separation from a significant adult

- rejection or not having a friend

- losing control (e.g., such as wetting oneself)

- being reprimanded or ‘getting in trouble’

- fear of the dark at night-time

- saying goodbye at school drop off

- trying new foods

- making decisions (e.g., who to play with, what to play)

- dealing with loss (e.g., broken toy or loss of a pet).

Research reading 8.2: Yeo, K., Frydenberg, E., Northam, E., & Deans, J. (2014). Coping with stress among preschool children and associations with anxiety level and controllability of situations. Australian Journal of Psychology, 66(2), 93–101. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajpy.12047

Charlotte explained to Yuwen that she thought that in the playworld, the children, as porcupines, could enter the desert. But the first problem they face is that it is night-time! They had not been prepared. And it is dark! In fact, so dark that they cannot see a thing! They could experience a range of feelings and emotions and need to be able to spot them and identify them, but also cope with them to solve their problems. The first problem the children will face is needing to find a light source! The Little Cactus could elicit ideas from the porcupines on what they could do (of course, with their eyes closed!). Some children might suggest torches, but it could be challenging because the children did not pack them. Others might suggest building a fire, which is a great idea.

Someone might ask, ‘Did anyone bring marshmallows?’ Thankfully, this is something the Little Cactus always carries, and then the children as porcupines and Charlotte as the Little Cactus can stop for a moment and share toasted marshmallows, relieved that they can see now that there is light.

But light was not the biggest problem! It turns out that cactuses do not like fire and all of a sudden, the Little Cactus is losing their prickles because they are too warm next to the fire. One by one, they dropped out. Oh no! Before the Little Cactus had time to respond, 10 had fallen onto the ground. He loved his spikes, and now 10 of them were gone forever. He starts to cry.

Practice reflection 8.7: What are the potential wellbeing concepts Charlotte is explaining to Yewen? Record your ideas in your Fleer’s Conceptual PlayWorlds thinking book.

Charlotte has learnt that wellbeing concepts can be brought out creatively in imaginary situations as children jump into the story of The Lonely Little Cactus. She also explained to Yuwen how she loved using playworlds to build wellbeing because she did not have to feel equipped and expert in teaching wellbeing as she was not teaching the concept explicitly. Rather, she was taking everyday scenarios like fear and loss and helping to elicit ideas from children on how they cope.

Practice reflection 8.8: In planning your Conceptual PlayWorld of your chosen story, what will be the authentic problem that arises? What concepts will act in service of building wellbeing through play? Record your ideas in the Conceptual PlayWorlds for Wellbeing proforma found in your Fleer’s Conceptual PlayWorld thinking book.

5. Being a Play Partner

This Conceptual PlayWorld for wellbeing creates multiple opportunities for the children to engage in wellbeing concepts. Charlotte, as the Little Cactus, could begin the Conceptual PlayWorld in the upper position, asking children to identify their feelings or possible feelings in the dark, brainstorming helpful and unhelpful ways to cope, trying different coping strategies and working out the best way forward. Possible prompt questions Charlotte could ask the children include:

‘How does being in the dark like this make you feel?’

‘Let’s think of all the things we can do – no matter what they are.’

‘What are the helpful ways we can cope with this? What are the unhelpful ways?’

‘Have you ever had to cope with a scary situation before? What helped?’

Once the Little Cactus loses spikes, Charlotte can take on an under position with the children in a collective upper position, providing insights into what she can do to feel better.

The children can offer ideas on how she can cope with the loss of her 10 spikes. They can continue talking about helpful ways of coping (e.g., talking to a friend, asking an adult for help) and unhelpful ways of coping (e.g., screaming, crying, rolling on the floor).

Returning to the upper position, Charlotte, as the cactus, can also draw from what helped her to cope last time when there was no light or draw from the past coping strategies that worked for the Little Cactus in the story.

Yuwen asks Charlotte, ‘How do you think Conceptual PlayWorlds that build wellbeing differ from other Conceptual PlayWorlds?’

Practice reflection 8.9: How do Conceptual PlayWorlds for wellbeing differ from other playworlds? Record your ideas in the Conceptual PlayWorlds for Wellbeing proforma found in your Fleer’s Conceptual PlayWorld thinking book.

From the perspective of young children, they will unlikely differentiate between playworlds targeting various educational concepts, be it STEM, literacy or wellbeing. Instead, they will hopefully be immersed in the narrative and the play. Their focus is not on the instructional goals but on the imaginative and interactive elements that make the playworld engaging. This underscores the significance of using play as an effective pedagogical tool for teaching complex concepts, including wellbeing. The child’s involvement in the narrative serves as a vehicle for learning, growth and development. All playworlds have potential to create meaningful, memorable, and intrinsically motivating learning opportunities.

Practice reflection 8.10: Finalise your own Conceptual PlayWorld for wellbeing for your chosen book. Record your ideas in the Conceptual PlayWorlds for Wellbeing proforma found in your Fleer’s Conceptual Playworld thinking book.

Conclusion

This chapter revisited Charlotte’s journey in learning Conceptual PlayWorlds. Her ability to implement a Conceptual PlayWorld to build wellbeing was driven first by her willingness to embrace a proactive approach to mental health in the early years. She learnt that wellbeing is a core determinant of children’s overall development and ability to handle adversity.

The chapter highlighted how Conceptual PlayWorlds aimed at promoting wellbeing differ from other playworlds, but also share similarities. While all playworlds foster a form of learning, those designed specifically for wellbeing weave in elements that directly support emotional development and competencies like coping skills. Moreover, such playworlds not only equip children with knowledge but also provide them with strategies and tools to address real-life challenges, fostering their ability to cope with various situations.

Despite feeling initially unprepared, Charlotte effectively used Conceptual PlayWorlds to enhance student wellbeing. Her learnings serve as an example of the power of educators in shaping children’s mental health and how supporting wellbeing does not always require additional expertise or training.

As we move forward in the book, it is essential to remember that the purpose of Conceptual PlayWorlds is not to replace the work of mental health professionals like psychologists but rather to complement it by embedding wellbeing-focused strategies into everyday learning scenarios. By doing so, teachers like Charlotte can foster an approach that is responsive to the needs of her students and proactive in strengthening mental health and wellbeing.

To find out more about Fleer’s Conceptual PlayWorld read the research on the Conceptual PlayLab website.

References

Allen, K. A. (2023). The lonely little cactus: A story about friendship and coping. Routledge.

Allen, K. A., Fleer, M., & McKinley, L. (2023). Conceptual playworlds for wellbeing: A practical resource for the lonely little cactus. Routledge.

Bakken, L., Brown, N., & Downing, B. (2017). Early childhood education: The long-term benefits. Journal of Research in Childhood Education, 31(2), 255–269. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02568543.2016.1273285

Bungay, H., & Vella-Burrows, T. (2013). The effects of participating in creative activities on the health and well-being of children and young people: A rapid review of the literature. Perspectives in Public Health, 133(1), 44-52. https://doi.org/10.1177/1757913912466946

Fleer, M. (2018). Conceptual Playworlds: the role of imagination in play and learning. Early years, 41(4) 253-364. https://doi.org/10.1080/09575146.2018.1549024

Frydenberg, E., Deans, J., & O’Brien, K. A. (2012). Developing everyday coping skills in the early years: Proactive strategies for supporting social and emotional development. Bloomsbury.

Graham, A., Phelps, R., Maddison, C., & Fitzgerald, R. (2011). Supporting children’s mental health in schools: Teacher views. Teachers and Teaching, 17(4), 479–496. https://doi.org/10.1080/13540602.2011.580525

Howard, J., & McInnes, K. (2013). The impact of children’s perception of an activity as play rather than not play on emotional well‐being. Child: Care, Health and Development, 39(5), 737-742. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2214.2012.01405.x

Layard, R., Clark, A. E., Cornaglia, F., Powdthavee, N., & Vernoit, J. (2014). What predicts a successful life? A life-course model of well-being. The Economic Journal, 124(580), F720–F738. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecoj.12170

Lee, R. L. T., Lane, S., Brown, G., Leung, C., Kwok, S. W. H., & Chan, S. W. C. (2020). Systematic review of the impact of unstructured play interventions to improve young children’s physical, social, and emotional wellbeing. Nursing & Health Sciences, 22(2), 184-196. https://doi.org/10.1111/nhs.12732

Mazzer, K. R., & Rickwood, D. J. (2015). Teachers’ role breadth and perceived efficacy in supporting student mental health. Advances in School Mental Health Promotion, 8(1), 29–41. https://doi.org/10.1080/1754730X.2014.978119

Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development [OECD]. (2020). Why early learning and child well-being matter. In Early learning and child well-being: A study of five-year-olds in England, Estonia, and the United States. OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/3990407f-en

Reinke, W. M., Stormont, M., Herman, K. C., Puri, R., & Goel, N. (2011). Supporting children’s mental health in schools: Teacher perceptions of needs, roles, and barriers. School Psychology Quarterly, 26(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0022714

Schoon, I., Nasim, B., Sehmi, R., & Cook, R. (2015). The impact of early life skills on later outcomes. OECD (Early Childhood Education and Care).

Seligman, M. E. (2011). Flourish: A visionary new understanding of happiness and wellbeing. Free Press

Shelemy, L., Harvey, K., & Waite, P. (2019). Secondary school teachers’ experiences of supporting mental health. The Journal of Mental Health Training, Education and Practice, 14(5), 372–383. https://doi.org/10.1108/JMHTEP-10-2018-0056

Silvey, P. E., Ben-Arieh, A., Casas, F., Frønes, I., & Korbin, J. (2014). Imagination, play, and the role of performing arts in the well-being of children. In A. Ben-Arieh, F. Casas, I. Frønes, & J. Korbin (Eds.), Handbook of child well-being (pp. 1079-1097). Springer.

Shoshani, A., & Slone, M. (2017). Positive education for young children: Effects of a positive psychology intervention for preschool children on subjective well being and learning behaviors. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, Article 1866. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01866

Waters, L., Dussert, D., & Loton, D. (2022). How do young children understand and action their own well-being? Positive psychology, student voice, and well-being literacy in early childhood. International Journal of Applied Positive Psychology, 7(1), 91–117. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41042-021-00056-w

Yeo, K., Frydenberg, E., Northam, E., & Deans, J. (2014). Coping with stress among preschool children and associations with anxiety level and controllability of situations. Australian Journal of Psychology, 66(2), 93–101. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajpy.12047

Attributions

“Figure 8.1.” by Adriana Alvarez, based on an image by Anne Suryani, is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0

“Figure 8.2.” by Kelly-Ann Allen is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0

“Figure 8.4.” by Kelly-Ann Allen is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0

“Figure 8.2.” by Kelly-Ann Allen is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0

“Figure 8.1.” by Adriana Alvarez, based on an image by Anne Suryani, is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0

Acknowledgments

Appreciation to Florence and Henry Allen for their contributions of illustrations to this chapter.