Chapter 10 : Conceptual PlayWorlds to study the structuring of time into days, weeks and months

Anne Clerc-Georgy and Myriam Garcia Perez

Chapter Goals

By reading and exploring the content of this chapter, you will learn:

- how dates (days, weeks and months) can be used for in early childhood

- why the use of knowledge promotes the construction of meaning

- how to maintain dramatic tension in a Conceptual PlayWorld.

Introduction : Jumping into the imaginary situation

Charlotte went to Switzerland. She wanted to visit her friend Michael, who works with a class of 4 and 5-year-olds. Michael is worried because his colleagues criticised him for not doing the ‘date of the day’ activity every morning. He disagrees and doesn’t understand the point of repeating the date every day, and he can’t get his students to do it. He asks Charlotte how children learn to use a calendar in Australia.

In this chapter, you will explore how young students construct temporal reference points, like days, weeks and months. You will help Michael and Charlotte find ways to work the meaning of using a calendar in Fleer’s Conceptual PlayWorld.

Additionally, in this chapter, you will reflect on how to support students’ motivation in a Conceptual PlayWorld.

But before you start understanding how Conceptual PlayWorlds can be used to build temporal concepts, read the story of Michael and find out why he disagrees with his colleagues.

Michael’s story – The morning calendar is a meaningless activity

Last week, in the teachers’ room, two colleagues confronted Michael. They criticised him for not working on the ‘date of the day‘ with his students. This is a problem because the students don’t know how to do it when they join the primary class. Michael replied that he didn’t find it interesting to recite a date every morning, especially when the students didn’t understand what it means.

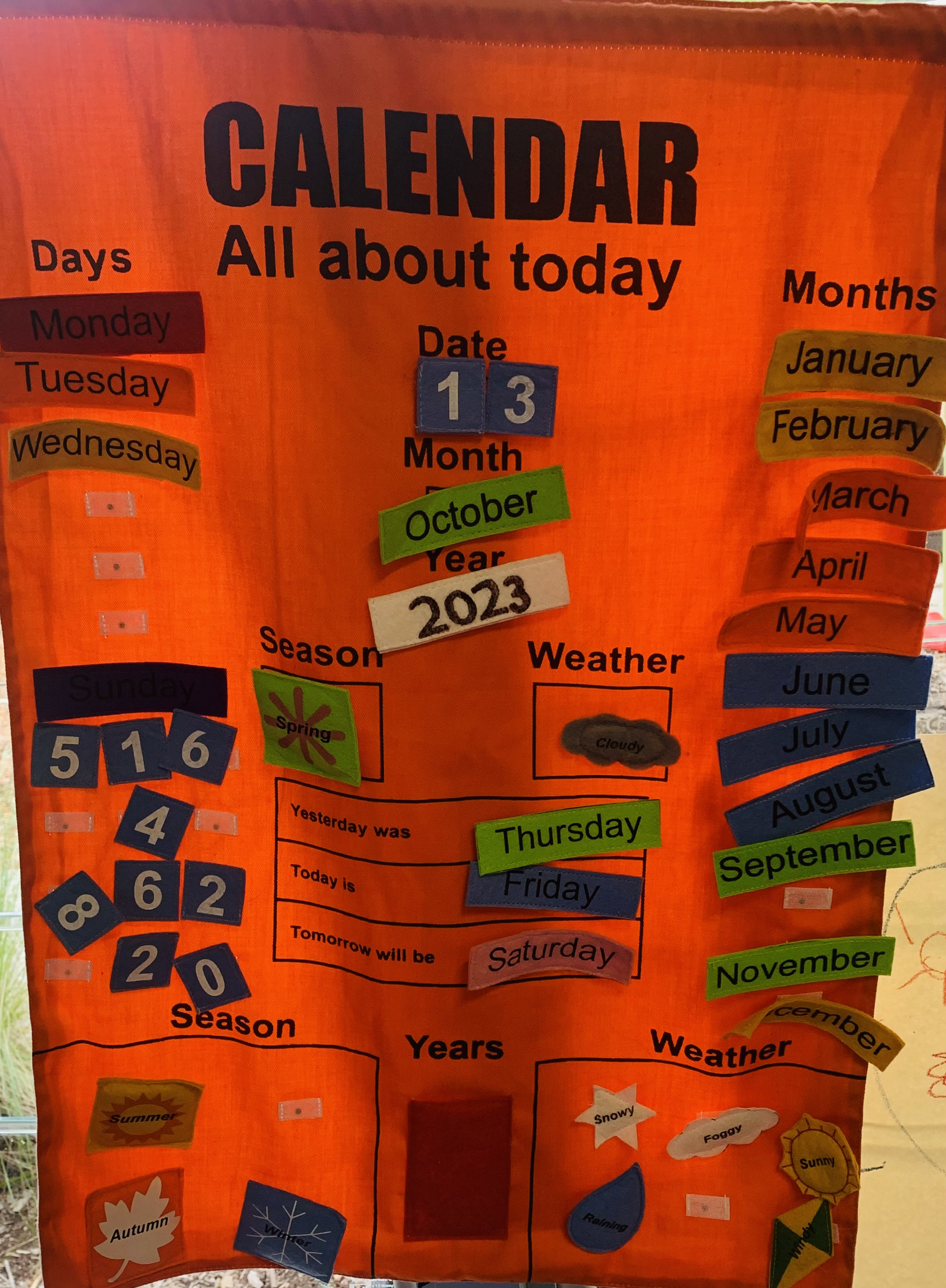

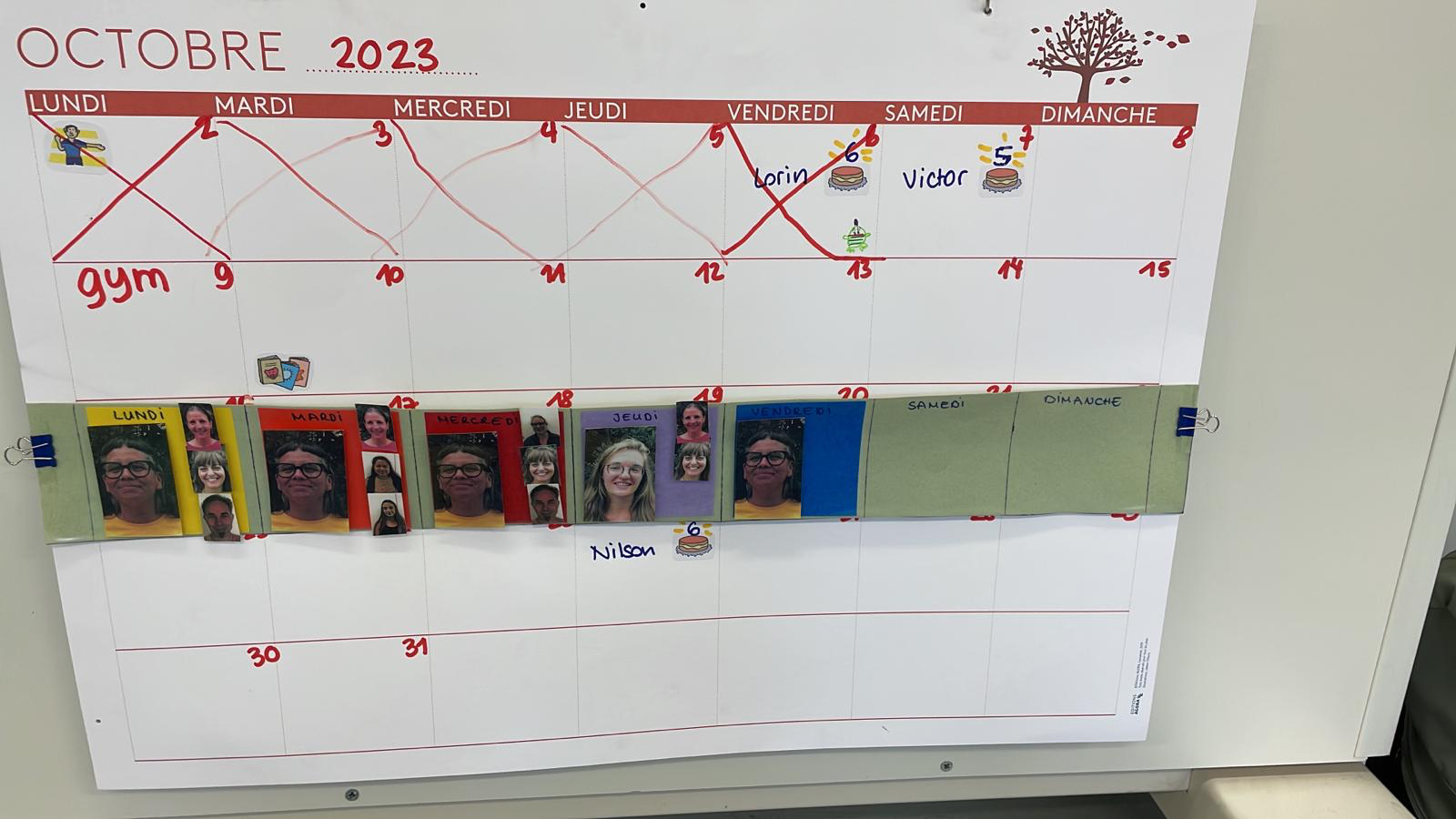

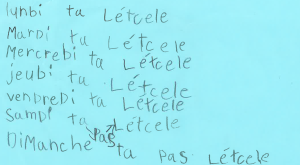

Figure 10.1

Class calendars

Note. Images provided by the author.

Michael tells Charlotte that he understands why his colleagues are upset but doesn’t see how a calendar routine could make sense to the children in his classroom. He would like to work on the calendar and today’s date with his students, but first, he needs to figure out a way to make it work in a meaningful way.

Charlotte suggested they reflect deeper together and imagine Fleer’s Conceptual PlayWorldWorld to work on the concepts underlying the calendar routine.

Practice reflection 10.1: Why do you think Michael’s colleagues are upset? How do you work with the calendar in your classroom? How useful do you think the ‘date‘ date of the day’ day’ activity is in the classroom? What do children learn from doing it? Record your thoughts in your personalised Fleer’s Conceptual PlayWorld thinking book.

Diving into the research

What does time structuring mean?

Throughout time, different civilisations have attempted to formalises the periodicity of certain phenomena (day/night alternance, moon cycles and the return of the seasons). Based on these facts, humans needed to structure and organise their lives by measuring time in a more concrete, predictable way. This was done either in the form of dates (to count days) or duration. According to Harris (2002), a famous psychologist, imagination probably emerged in sedentary men in connection with their need to measure life (they knew they were mortal) and to anticipate the future (harvests, seasons, etc.).

In our civilisation, we have organised the days into groups of 7 (weeks). We’ve also divided the year into 12 months and the months into about 4 weeks. This is the result of numerous adaptations since, unfortunately, there isn’t an exact number of moon cycles (months) in one sun cycle (year). In addition, we have divided the day into hours, minutes, seconds, and so on.

By measuring time this way, we can find out how long we’ve been born, how many days we have left before the summer holidays, when we can meet up with a friend, etc. However we’ve agreed on measuring objective time, but it doesn’t correspond to our subjective experience. An hour at the dentist’s isn’t exactly the same as an hour playing with friends!

Figure 10.2

What will the children learn about time?

Around age 5, children will become aware that time passes irreversibly. They will learn certain conventional concepts, such as the days of the week or the months of the year, and thus learn to orient themselves in time (today is Friday, October 13, it’s morning; what day will it be tomorrow?). They will also learn to tell the time and organise events in time (my birthday is in February; I go to music lessons on Tuesdays). Finally, from a language point of view, children will learn to use verb tenses and time words (before, yesterday, later, it’s a long time, etc.).

In pretend play, children develop their ability to imagine, anticipate, bring into existence what is not yet. At the same time, imagination is shaped by elements drawn from past experience. More specifically, when playing, children use their imagination to postpone actions and desires, to wait, anticipate and plan actions. Thus, play is ideal for expanding, transforming and structuring children’s relationship with time.

Let’s go back to Michael’s question. What’s the point of using a calendar or working on the day’s date with 5-year-olds?

Practice reflection 10.2: In what situations do you use a diary or calendar? How do you do it? What does it help you achieve? Record your answers in the Fleer’s Conceptual PlayWorld thinking book.

A Conceptual PlayWorld for making sense of temporal concepts

Fleer’s Conceptual PlayWorld is particularly relevant for exploring temporal concepts. First, because imaginary scenarios allow children to go back and forth in time. It’s common for children to go back in time or leap forward into other times as they play. Second, pretend play continually invites children to plan or anticipate actions, i.e. to imagine actions before they happen or to order actions in relation to each other and thus situate them in the future. Finally, the construction of temporal notions is closely linked to the development of imagination. Indeed, to navigate in time, it is essential imagine different past or future situations.

More specifically, Fleer’s Conceptual PlayWorld offers numerous possibilities for organising time in terms of days or weeks and using a diary. Numerous dramatic situations invite children to situate themselves in time, measure past time or anticipate dates to set future events.

Your role is to help Michael and Charlotte imagine dramatic events that involve situating oneself in time and anticipating a date in the future through these suggested steps :

- Choose a story that requires you to place yourself in time and anticipate a date.

- Plan a Conceptual PlayWorld.

- Plan how to jump into the story (enter and exit the playworld).

- Create an authentic problem of location in the calendar.

- Be a play partner and anticipate ways to support children’s motivation.

Let’s get to it!

Planning a Conceptual PlayWorld for building temporal concepts

Getting prepared

Michael and Charlotte read widely on development of temporal concepts in early childhood. They also sought to understand the situations in which a calendar or diary is helpful and how it enhances the ability to act, remember, plan or communicate. Finally, they examined their thinking patterns when using their diaries.

On the Fleer’s Conceptual PlayWorld website you will find a planning proforma for Fleer’s Conceptual PlayWorld. This is the website and planning framework that Yuwen showed to Charlotte and which she passed on to Michael. In Appendix B, there is an example of a planning proforma which was designed for infant and toddler children.

1. Choosing a story

Charlotte and Michael spent a lot of time looking for a story for their Conceptual PlayWorld. Many of the stories available in school materials didn’t contain enough drama or, more importantly, didn’t invite the readers to empathise with the characters.

Practice reflection 10.3: Help Michael in his quest for stories. What do you think makes children empathise with a character? Record your answers in the Fleer’s Conceptual PlayWorld thinking book.

Figure 10.3

Michael shows Charlotte the book he found.

They agreed to select King of the SWAMP. This book tells the story of Mac Gadouille, who lives in a disgusting swamp. He learns that the King wants to destroy it to build a skate park. He decides to transform the swamp into a magnificent flower garden. The King gives him 10 days to prove that such a beautiful place shouldn’t be destroyed. Unfortunately, shortly before the King’s visit, Mac Gadouille discovers caterpillars eating all his flowers. The King will have to wait until the day when all the caterpillars become butterflies, because on that day, the marsh will be even more beautiful and colourful. The question is, when is the King due for this visit?

This is a fantastic book for exploring the world of dates and diaries. Indeed, there are several references to days to look forward to or anticipate.

Charlotte is pleased with the book’s choice made with Michael. She decides to plan and participate in this future Conceptual PlayWorld with him. Michael explains that this story allows us to pose the problem of dates and days passing over and over again, specifically at three moments in the story: First, when the King announces that he will return in 10 days. Then, when Mac Gadouille discovers the caterpillars and has to anticipate how long it will take them to become butterflies. Finally, when Mac Gadouille must set a date to invite the King to visit his marsh. Charlotte congratulates him on all his good ideas.

Practice reflection 10.4: Do you know of any other stories that involve counting days, measuring time or setting dates and appointments? Record your answers in the Fleer’s Conceptual PlayWorld thinking book.

2. Planning a Conceptual PlayWorld space

Michael and Charlotte decide to organise three areas in the classroom:

- The space for reading the story and working on the calendar near the blackboard, on the floor.

- The office of the scientist who knows all about caterpillars and butterflies.

- The rest of the classroom, which represents the swamp where Mac Gadouille lives.

Michael is worried about transforming the classroom and adding flowers and caterpillars. Charlotte reassures him: The children don’t need all that. She knows Michael can take them to a beautiful imaginary garden.

3. Planning how to jump into the story

Charlotte explains to Michael that defining how he will mark the entrance to and exit from the imaginary world is important. Michael suggests passing under her desk. He thinks this will help the children enter the extraordinary garden even better.

Practice reflection 10.5: What do you think of Michael’s idea? How would you help children enter the PlayWorld? Record your answers in the Fleer’s Conceptual PlayWorld thinking book.

Figure 10.4

Michael and Charlotte read together

Charlotte explains to Michael that it’s important to decide on everyone’s roles. Michael says he would narrate the story and then play Mac Gadouille in the playworld. All the children would be the swamp’s inhabitants and belong to Mac Gadouille’s family. Charlotte suggests that she play two roles. In the playworld, she would be the scientist explaining the life cycles of caterpillars and butterflies. She would also play the King but through the telephone. That way, she would call Mac Gadouille to arrange meetings.

4. Creating an authentic problem

Charlotte then asks Michael what the children’s real problem will be. Michael thought long and hard about it and after having read the story over and over again, he explains to Charlotte that the children would be facing two problems. The main problem would be to set the date for the King’s arrival right when the caterpillars have all become butterflies. But to do this, the children would need to answer another problem: they would need to find out how long it takes for the caterpillars to transform.

Michael and Charlotte talk for a long time. Michael wonders how they will get the kids to empathise with Mac Gadouille, and how they will motivate them to do the work of understanding the calendar.

Michael decides that he will start by reading the beginning of the story to the children. He’ll explain that Mac Gadouille and his family will transform the swamp into a beautiful garden. Then they’ll enter the playworld and go gardening together. After a while, when the garden starts to bloom, Michael//Mac Gadouille would call for help because he would find a caterpillar nibbling the flowers, before noticing there are hundreds of them!

Charlotte reminds him that sharing his emotions of surprise, helplessness, and maybe a bit of disgust with all the children would be particularly important at that moment. Later on, another crucial event would happen in the story: the King would call to announce his arrival. Mac Gadouille would ask him to wait a few days, promising he would call back soon to invite him.

Everyone would then leave the playworld and visit Charlotte, the scientist, who would explain the butterfly life cycle by showing on a time strip (in days and weeks) how many days it takes for the caterpillars to become butterflies. When the children have memorised this number of days, they’ll go to the calendar to:

1. identify what day it is

2. count the days needed for the caterpillars to become butterflies, and

3. identify the date to invite the King for a visit to the swamp.

Then, Michael/Mac Gadouille could call the King.

Michael is really happy. He’s finally found a learning situation where using the calendar makes sense for him. He now understands the importance of how to use it and why children need to be supported in this learning process.

Practice reflection 10.6: What about you? Have you now a better understanding of the importance of calendars and diaries? What has changed? How can you help your students understand it too? What new ideas do you have on the subject? Record your answers in the Fleer’s Conceptual PlayWorld thinking book.

4. Being a play partner

To engage themselves and the children in the play about the diary, Michael and Charlotte felt that they first had to get them into the swamp. They must see it as their own home. Then they imagined what Michael//Mac Gadouille would tell them and how he would engage the children.

Upon entering the playworld they would say:

‘There is mud everywhere and it smells bad!’

‘It is dirty!’

‘Be careful where you step, I’m sinking into the mud and will fall!’

‘Try to walk on the stones!’

Then, to motivate them to work on transforming the marsh into a beautiful garden:

‘I am planting a flower here. It’s beautiful! This flower is so amazing!’

‘Oh, the seeds have grown. Look! The flowers are blue, yellow, red…’

‘Mmmmh, how nice it smells in our garden.’

‘I think we’re ready for the King’s visit!’

When they discover caterpillars :

‘Oh no! That is awful, a caterpillar. Oh! Another one, and another one here… Thousands of caterpillars, can you see them?’

‘They are going to eat all our flowers, it’s horrible!’

‘We will have to leave the swamp. If the King sees this disaster, he’ll destroy everything!’

‘Help me, what can we do?’

After the King’s phone call:

‘I have an idea. When all these caterpillars become butterflies, the swamp will be even more beautiful and colourful, right? But how do we know when that will happen?’

For her part, Charlotte, as the King, had been thinking about the telephone call. She really wanted to impress and engage the children in solving the problem. She, therefore, imagined she could say:

‘Hello, I am the King. I am on the way. I am coming to visit your stinking swamp. I’m going to destroy everything in your swamp. I am finally going to build my skate park. I am happy. Don’t make me think it is a beautiful place. You are just stinky pickles!’

5. Maintaining dramatic tension

During the implementation of the Conceptual PlayWorld, the children were fully involved in the play. They followed Michael into the swamp, imagined his transformation and got angry with the King. In this way, they easily retained the scientist’s lessons. They memorised the 12 days it would take for the caterpillars to transform into butterflies. They then worked with Michael to identify the day’s date and count the 12 days.

At one point during the calendar work, some of the children showed signs of declining motivation. Charlotte, who was observing the children, decided to leave the classroom and take on the role of the King to call Michael/Mac Gadouille again. This new, unplanned intervention, re-created the dramatic tension that motivated the students to resolve the question of the date for the King’s invitation. Charlotte, as the King, threatened to arrive right away if he didn’t receive the invitation date soon.

Practice reflection 10.7: If, like Charlotte, you perceive a drop in motivation or dramatic tension in a Conceptual PlayWorld, what are your tools for recreating that tension to get your students on board again? Record your answers in the Fleer’s Conceptual PlayWorld thinking book.

Conclusion

Charlotte is very excited about her experience with Michael. On the way back to her hotel, she can’t resist emailing Yuwen to tell her what she’s learned during her stay.

Dear Yuwen,

I’ve just had a wonderful experience in Michael’s kindergarten class in Switzerland. It completely transformed my understanding of the value of learning to use a calendar with these young students. In our Conceptual PlayWorld, we were able to make this a necessity. Indeed, the calendar becomes indispensable when we need to situate ourselves in time to anticipate and communicate an upcoming date.

Furthermore, when we were implementing Fleer’s Conceptual PlayWorld, I noticed that the children sometimes needed us to support their motivation. I proudly identified a moment when this motivation was declining. I then intervened, phoning the children to stimulate the dramatic tension and motivate them to solve the calendar problem. It worked!

I look forward to coming back to Melbourne to tell you about my adventure.

Sincerely,

Charlotte

To find out more about Fleer’s Conceptual PlayWorlds read the research on the Conceptual PlayLab website.

References

Harris, P. (2007). L’Imagination chez l’enfant : son rôle crucial dans le développement cognitif et affectif. Retz.

Attributions

“Figure 10.1.” by Anne Clerc-Georgy is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0

“Figure 10.3.” by Adriana Alvarez, based on an image by Anne Suryani, is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0

“Figure 10.4.” by Adriana Alvarez, based on an image by Anne Suryani, is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0