Chapter 3: Play Role, drama and learning concepts in a Conceptual PlayWorld

Liang Li

Chapter Goals

By reading and exploring the content of this chapter, you will learn:

- how to become a play/character role in a Conceptual PlayWorld

- how to dramatise the conceptual problem in a Conceptual PlayWorld

- how to act and embody subject knowledge/concepts in play

Introduction – Entering an imagined Conceptual PlayWorld

You are about to enter the imaginary world of an early childhood centre.

After learning about the Conceptual PlayWorld from Yuwen (see Chapter 1), Charlotte was keen to try her own Conceptual PlayWorld for the first time. Charlotte chose the storybook, The Gruffalo (Australia only) written by Julia Donaldson and Axel Scheffler.

Charlotte chose this story as she wanted the children to identify with the mouse, because although the mouse was little, the mouse always came up with many clever plans to save herself. She wanted to use this story to help the children understand that even though they are small, they can still find a way to ‘save’ themselves in any challenging situation.

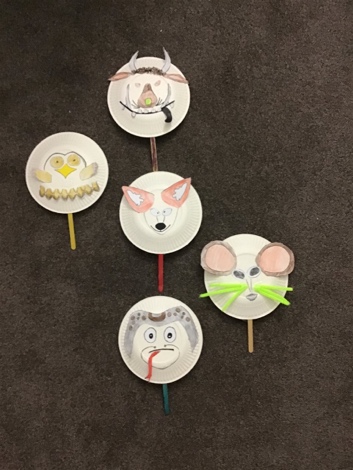

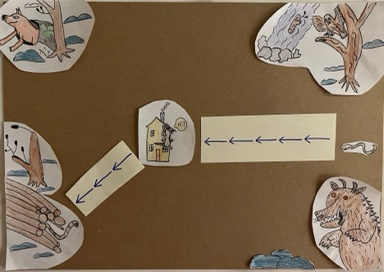

It was the first time the children were to travel to the Conceptual PlayWorld space, which was set up in the centre of their playroom. Before entering the Conceptual PlayWorld, Charlotte and the children read the story together and designed different character roles using art materials (Figure 3.1.) to create character puppets and develop scripts for the play.

Figure 3.1.

Character puppets for use in the Conceptual PlayWorld

They created a new storyline and narrated an ending where all the animals, even the Gruffalo, became friends. After entering the playworld, the children actively performed their chosen character roles, acting out the new storyline and following the prepared script. Charlotte acted like a director of their play, giving them suggestions of what and how to perform, while Yuwen watched on. After the session, Charlotte asked Yuwen if this was how Conceptual PlayWorld should be experienced, feeling like it was very similar to theatre play she had previously done in her preservice teacher training.

Practice reflection 3.1: How do you feel about the Conceptual PlayWorld that Charlotte has created? Can you see what problems arose based on your understanding of Conceptual PlayWorld from Chapter 1? Could you help Charlotte solve the problems according to what you have learned? Record your thoughts in your personalised Fleer’s Conceptual PlayWorld thinking book.

Double-subjectivity: Play role and real role

Through her first experience of the Conceptual PlayWorld, Charlotte reflected on her teaching role and wondered about the differences between theatre play and Conceptual PlayWorld. Yuwen suggested that an important element Charlotte did well was thinking about supporting the children in building an emotional connection with the characters in the storybook. Charlotte used theatre play to support the children to be familiar with the storyline and develop a new ending. This helped the children to transition to the imagined playworld space. Yuwen also mentioned that Charlotte’s professional reflection was beneficial, and her question about the difference between a Conceptual PlayWorld and theatre play was important. Yuwen explained the differences between theatre play and Conceptual PlayWorld to Charlotte and elaborated upon the importance of being an active play partner in Conceptual PlayWorlds.

Yuwen: It is good that you chose a storybook that has an adventure and an emotionally charged situation, such as what the little mouse experienced, and which followed the children’s perspectives. The Conceptual PlayWorld starts with children’s literature, which is why the book you chose was just great. However, within the Conceptual PlayWorld, teachers also need to be part of the playworld. We call this taking a partner role. Acting out the story is just a start to help the children become familiar with the character roles and build emotional connections with the storybook’s characters. In this way, the Conceptual PlayWorld can be personally meaningful for children. Teachers need to enter the Conceptual PlayWorld together with the children by taking a character role instead of being a director of the children’s play. The director’s role is outside of the imagined play. To be inside the play, teachers can be a role from the storybook or even a new character role that might not come from the story at all! The teacher can even take on the role of an object, like a tree, who can guide the children and promote the play and exploration process (See Figure 3.2). Some teachers worry that they cannot control the classroom and manage children’s behaviours, especially when going inside together with a whole group, so they might choose a character role who has magic powers, which will inspire the children.

Charlotte (nodding her head): Oh, it means I need to be an animal friend drawing upon the story or other character role. I thought I was part of their play as a director taking a play role instead of being a teacher. Now I can see that I need to be an active player. But why do we need to take such an active role? And how to be an active player? It feels quite challenging to play a role with children, acting like an animal. I’m not sure I am playful enough.

Yuwen: Very good questions Charlotte! Why do teachers need to be part of the Conceptual PlayWorld? Think about if you become a play role such as an owl, what is your role in the children’s eyes? As a teacher? Or an owl? In their eyes, you become an owl! Once you are inside the imaginary situation, you can better understand the children’s perspectives and intentions. Then, you can use your character role to guide the children to investigate the conceptual problem. While in a character role in the Conceptual PlayWorld, it doesn’t mean you forget your real role as a teacher. Rather, simultaneously, you have what is called double-subjectivity (Kravtsova, 2014): a player who is a play partner of the children and a teacher who has a pedagogical agenda. By doing so, you can teach the subject knowledge and concepts and support meaningful learning and play development.

Figure 3.2

Charlotte could be a tree

Practice reflection 3.2: What are the relations between a play role and a real role? Why do we need to become play partners in the Conceptual PlayWorld?

After listening to Yuwen’s explanation and suggestions, Charlotte shared another concern due to her lack of confidence in being in the play role within the Conceptual PlayWorld.

Charlotte: Oh! Very interesting to know this. I haven’t thought about this before. It is important to hold two roles at the same time. Now I know what I should do. However, I still find it challenging to act like an animal or be playful, as I have never played like that before. I am so worried about how the children will see me. Also, I am not sure how to use my role to extend children’s thinking and exploration?

Yuwen: Please don’t worry. We can do some playful activities together, and I can invite other colleagues to the professional training day this week. We can do some improvising activities and support you to be more playful.

Later, at the professional training day within the whole centre, Yuwen leads the whole group of teachers to do the improvised activities she discussed with Charlotte. The webpage Demonstrating Viola Spolin’s Theater Games has examples of the theatre games used in the training day.

Practice reflection 3.3: What improvisation principles could you use to extend the children’s imagination and play in your classroom? Can you use improvisation principles in daily conversation? Why do you think they are important in a Conceptual PlayWorld? Record your thoughts in your personalised Fleer’s Conceptual PlayWorld thinking book.

Embodied imagined play role and concepts

During the professional training session, Yuwen created a conceptual play activity to explore the embodied imagined STEM concepts. This supported Charlotte’s understanding of the STEM concepts and help her transition to an imaginary situation.

Conceptual play activity

Professional training participants, as a small group, portray the assigned scientific concepts without using words. Others need to guess the concept which has been portrayed, such concepts can include such as:

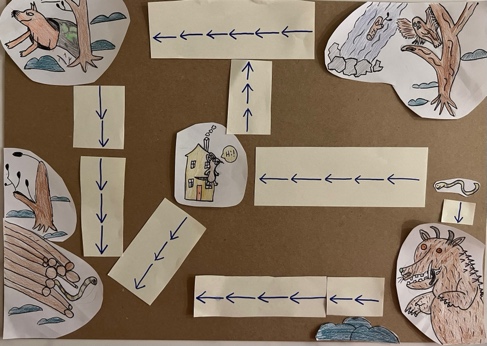

- Direction: Directional movement through the arrows and walking steps

- 2D shapes: Triangle, Square, Rectangle, or Circle

- Germination: A plant grows from a seed into a seedling

- Freezing & melting: Ice melting into water on a sunny day

- Light refraction: Rainbow

Figure 3.3.

Acting the directional movement

Practice reflection 3.4: How do you feel about using body movements and gestures to illustrate the scientific concepts? Have a practice with your friends, family or colleagues and see if they can guess which concepts you are trying to portray.

After the professional development training day, Charlotte debriefed with Yuwen and reflected on the conceptual play activity.

Charlotte: I found I really enjoyed the conceptual play activity. It was a fun and interesting activity. I could create anything I liked using my body movements and the related objects. I changed the meaning of my actions and objects by interacting with the group imagination. It really opened my mind, and I was amazed how I could dramatise the concepts using an imagined play role. Play has such a powerful meaning!

Is the Conceptual PlayWorld scripted?

After the professional development training session, Charlotte reflected on what she learnt with Yuwen and explained the importance of improvisation and how this also supported the children’s play development. As Charlotte wanted to do it right, when she first tried the Conceptual PlayWorld session, she had a script ready, but now reflected on that decision with Yuwen:

Charlotte: Thanks for all your great ideas, Yuwen. I now feel I know how to extend the children’s thinking by stepping out of my role as the teacher and, instead, use the play role, which motivates the children to explore the concepts. I still have another question though: is the Conceptual PlayWorld scripted? Should I prepare every sentence to guide the children’s exploration of the concept in the Conceptual PlayWorld?

In response, Yuwen discussed with Charlotte the planning process of the Conceptual PlayWorld and highlighted how to plan and dramatise the conceptual problem while considering children’s learning processes:

Yuwen: Excellent thinking Charlotte! I am so glad to hear that you feel more comfortable with being in a play role. Also, you have asked another great question. The Conceptual PlayWorld needs to be planned; however, it should not be scripted, or cannot be scripted, as we do not know how the children will interact with the problem-solving scenario in the imagined Conceptual PlayWorld. What we can plan, though, is the dramatisation of the emotionally charged situation that motivates children’s exploration of the problem. While doing this, we also assess children’s play and their exploration process (see Chapter 5 for more information about assessment).

For instance, you might plan your imagined role in play and the dramatised conceptual problem for children and teachers to investigate together. In addition, you can plan the teachers’ interaction, all while considering children’s diverse needs and intentions. For instance, you might invite the characters to explore the concept of direction and say that the little snake was lost in the forest and could not find a way home. Then, the little snake met the Gruffalo and asked for help to find the way home, so needing directions. Within the Conceptual PlayWorlds, the children could use the concept of direction to help the snake and solve this emotionally charged situation of the poor snake being lost. Or you could create the emotionally charged scenario where the children in their character roles need to build a new house for the snake, as they could not find Snake’s old house and want to build them a new house. In this way, engineering principles could be applied, and the children can use design technology concepts to support the problem-solving process.

Authentic problem: Curriculum links and learning subject knowledge/concepts

Through their discussion, Charlotte has reflected on what Yuwen suggests and asks another important question related to the dramatisation of the authentic conceptual problem:

Charlotte: So, does it mean that in the Conceptual PlayWorld, the children’s learning process is reflected through the problem-solving process using relevant concepts? I wonder which concept I should start with?! For instance, if we would like children to learn the concept of direction, should I start with directional language? Or learning about maps? How can I embed the concepts into the Conceptual PlayWorld?

Yuwen: This requires us as teachers to be familiar with the curriculum and the children’s learning sequences with concepts and, in your example, direction. We aim to support children’s learning progression. We are not expecting the children to solve the problem in one day, rather, it may take a few sessions of the Conceptual PlayWorld to solve the problem. But we do need to start by setting up the emotionally charged scenario. For instance, while the children travel to the Gruffalo’s PlayWorld as different characters, such as a mouse, owl, snake or even the Gruffalo, the teacher might take on the role of a baby snake, explaining that she is lost in the deep dark wood, and needs help to find her way home.

Charlotte: That is a great idea! I could use our outdoor play yard to become Gruffalo’s playworld space. I could set up different areas representing the different animals’ houses. I could invite the children to explore these areas together with me. We could even have a community walk. After the first session of Conceptual PlayWorld, I will become a baby snake, lost and afraid and needing help to find my way home. The children could be other character roles to guide me, the lost baby snake, home. While they do this, I could prompt with questions like, should I go left or right, move forward or backward from the fox house? How many walking steps should I take?

Yuwen gives Charlotte a big smile and agrees with Charlotte’s creative ideas and thoughtful planning. She supports Charlotte in reflecting on the importance of planning the conceptual problems by considering children’s learning progression and curriculum content. Yuwen highlights that the play will hold significant meaning to the children through the dramatisation.

Yuwen: It sounds like a great idea. The directional language is used here to help solve the problem. Also, by counting steps, the children will be using the one-to-one correspondence principle. The measurement of the distance will also be important. But can you see how the Conceptual PlayWorld is not scripted? We must assess children’s learning and exploration while we play and explore with children together. For instance, if some children feel challenged counting the steps, we might spend more time counting and helping them to support counting between two animal houses (see Chapter 6 for more information about pedagogical positioning to support concept learning in mathematics).

Charlotte: Yes, thank you, Yuwen. Now, it is becoming so much clearer to me. I need to follow children’s intentions. Also, I think I could draw a map with the children while we help the baby snake find the house.

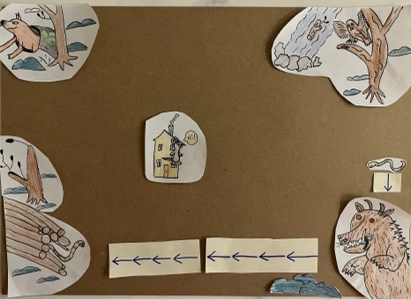

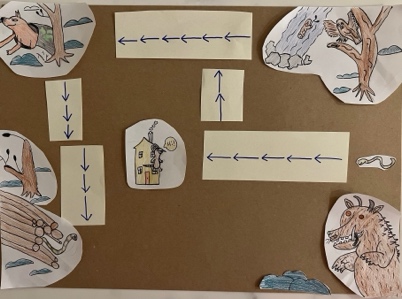

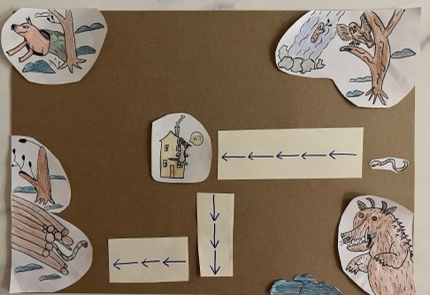

The following images demonstrate progressively exploring the concept of direction within a Conceptual PlayWorld.

Figure 3.4. Solution 1 Figure 3.5. Solution 2 Figure 3.6. Solution 3

Figure 3.7. Solution 4 Figure 3.8. All the possible solutions

Note. Images provided by the author.

Practice reflection 3.5: Can you think of another dramatic conceptual problem you could plan for children’s STEM exploration, drawing upon the story of The Gruffalo? How would you design the learning process while considering children’s learning progression of the concept? Record your thoughts in your personalised Fleer’s Conceptual PlayWorld thinking book.

Conclusion

One of the ideas introduced in Chapter 1 was the role of the teacher and dramatisation of the concepts in a Conceptual PlayWorld. In this chapter, you are invited to think about how you feel about being a play partner, setting up the drama of a problem, and acting and embodying the subject knowledge through play. To resource this challenge, this chapter provides information that will increase your capacities and build confidence in understanding and implementing the Conceptual PlayWorld in a play-based learning program.

To find out more about Fleer’s Conceptual PlayWorld read the research on the Conceptual PlayLab website.

References

Kravtsova, E. (2014). Play in the non-classical psychology of L.S. Vygotsky. In L. Brooker, M. Blaise & S. Edwards, The Sage handbook of play and learning in early childhood, 21-30. Sage.

Attributions

“Figure 3.1.” by Liang Li is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0

“Figure 3.2.” by Adriana Alvarez, based on an image by Anne Suryani, is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0

“Figure 3.3.” by Adriana Alvarez, based on an image by Anne Suryani, is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0

“Figures 3.4-3.8” by Liang Li are licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0

Theatre play is a kind of drama as a form of performance that children and educators act out the storyline or scripts based on the children’s literature.

Double-subjectivity means the teachers can be a play partner of the children and hold a teaching role who has a pedagogical agenda simultaneously in the play.