Chapter 7: Conceptual PlayWorld: fostering language and literacy learning

Janet Scull

Chapter Goals

By reading and exploring the content of this chapter, you will learn about:

- children’s play-based language and literacy learning

- textual features that foster children’s language and literacy learning

- how to use Fleer’s Conceptual PlayWorld to foster literacy learning.

Introduction – Jumping into the Imaginary Situation

This chapter continues to follow the learning journey of Charlotte as she explores children’s play-based language and literacy learning. Co-planning with Yuwen, her mentor teacher, they discuss how they can create an authentic context to enhance children’s literacy learning using Fleer’s Conceptual PlayWorld.

Exploring the Research

To ensure her practice is well grounded in research, Yuwen suggests Charlotte review the research that considers how play supports children’s literacy learning, with a focus on language and early writing.

Reading to children is a well-established practice in early childhood. It builds the linguistic resources and print awareness skills children need as they learn to read (Dickinson et al., 2012). Alongside learning about print, book reading creates opportunities for children to hear the pattern and sounds of words with opportunities ‘to play with words the beginning of a more sophisticated understanding of how language works’ (Raban, 2018, p.57). Moreover, the language of text often moves beyond conversational speech. Through listening to printed text read aloud, children are introduced to new vocabulary and begin to extend their understanding and expectations of the syntactic complexity of written language (Raban & Scull, 2023). Yet, equally important are the intertextual conversations that occur as texts are read to children. As active interlocutors, children build their comprehension of the story and are encouraged to use words in new contexts, which promote the construction of meaning outside their own experiences (Massey et al., 2008). The shared narrative builds shared understandings and language that can be reinforced and extended through talk and play.

Play also creates authentic opportunities for text production and it is in such moments that children can develop and extend their early conceptions of writing (Peterson & Rajendram, 2019). During and through their play, children become composers of text as they assign meaning to their drawing and mark-making, demonstrating a clear awareness of the interconnectedness between the symbolic nature of oral and written language (Scull & O’Grady, 2022). Likewise, we know the importance of the social contexts that shape and surround the texts produced and how children’s interaction with adults advances literacy learning (Dyson, 1999; Compton-Lilly, 2014). As adults write for and with children, concepts such as the permanency of text and the conventions used to encode meaning are further developed. Just as when reading to children, adults engaging children in writing model the discourse patterns of written texts, characterised as more integrated, detached, and explicit than oral language (Raban & Scull, 2023). Educators need to see and highlight the links across the modes of literacy as they support children to apply their early literacy learning to an increasing range of contexts and to extend their understanding of more complex texts in reading and writing.

Research Reading 7.1: Review the selected references listed below to learn more about early literacy.

Bingham G. E. & Gerde, H.K. (2023) Early childhood teachers’ writing beliefs and practices. Front. Psychol. 14: 1236652.doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1236652

Dickinson, D.K., Griffith, J.A., Golinkoff, R. M. & Hirsh-Pasek, K. (2012.) How reading books fosters language development around the world. Child Development Research Volume 2012, Article ID 602807, 15 pages doi:10.1155/2012/60280

Selecting the Text

Convinced of the opportunities play-based literacy provides, Charlotte was keen to continue her explorations. However, the first step was to select a text that allowed her to engage the children in the problem–based premise that underpins Fleer’s Conceptual PlayWorld while meeting curriculum expectations and priorities. Educators in Australia must extend and enrich children’s learning guided by the national curriculum framework Belonging, Being and Becoming: The Early Years Framework for Australia (ADGE 2022). This document informs ‘educational programs and practices that are place-based and relevant to that community’ (ADGE, 2022. p.4).

Drawing on the children’s recent interest in Australian animals and the curriculum expectation that children are connected to and contribute to their world, becoming socially responsible with respect for the environment, Yuwen encouraged Charlotte to explore the basic needs of living things (AGDE, 2022). This could be achieved as children learn to care for native animals and protect and improve the environment for wildlife with connections to the concepts of environmental sustainability. Further, this would coincidently engage the children in early literacy concepts to develop children’s understanding of the communicative intent of texts and advance their symbolic awareness of print and written language.

With this in mind, Charlotte recalled her enjoyment of reading Wombat Stew (Vaughan & Lofts, 1984) and decided to check the suitability of this text regarding the five characteristics of a Conceptual PlayWorld for the intentional teaching of STEM (Fleer, 2022).

Both Yuwen and Charlotte agreed that the children would relate to the drama of the story and develop empathy for the characters as their play involved saving the wombat. The plot also introduces a new problem: how to continue caring for the rescued wombat. This would engage the children in STEM concepts related to developing an understanding of natural worlds and sustainable ecologies for Australia’s native animals.

This video provides an excellent animated read-aloud version of Wombat Stew.

Alternatively, you can watch a teacher read Wombat Stew to children.

However, with a language and literacy focus, it was important for Charlotte to better understand the linguistic structure and features of the text as a springboard for children’s learning. Working together, Yuwen supported Charlotte in conducting a linguistic analysis of the text to foster children’s language and literacy development. Together, they examined the text, focusing on elements particular to the young children in their care.

Features of the text

Phonological Awareness

Wombat Stew draws attention to the patterning and sounds of language using rhyme, rhythm and repetition as key linguistic elements. Most obvious is the repeated refrain with rhythm emphasised when read with a cadence reflective of a sing-song pattern.

Wombat stew,

Wombat stew,

Gooey, brewy,

Yummy, chewy,

Wombat stew.

Rhyme is prominent throughout the text. In addition to the rhyming pairs above, other playful examples include ‘crunchy, munchy and lunchy’, also ‘spicy and nicey’. The patterning of language is also apparent through alliteration, the repetition of the same sound at the start of a sequence of words often used to provide a lyrical effect. Examples in the text include ‘bubbling billy’ and ‘creepy crawlies’.

Vocabulary

The text contains vocabulary that may be new to young children, including ambling, brewing, graceful, fluttered and scribble.

Narrative Structure

Wombat Stew follows the grammar of a traditional narrative. The story commences with an orientation that introduces the setting as the billabong and the central characters, the dingo and wombat. As a problem to overcome, the complication is that the dingo has captured the wombat to make wombat stew, followed by a series of actions by different animals to trick the dingo with the resolution or problem solved as the wombat is saved.

Practice Reflection 7.1: Using Charlotte’s analysis of Wombat Stew as a model, complete a linguistic analysis of a text of your choice. What text elements will you focus on as you read and discuss the story? Record your answers in your Fleer’s Conceptual Playworld thinking book.

Addressing Fleer’s Conceptual PlayWorld Pedagogical Characteristics

With the text selected Yuwen and Charlotte considered the remaining Conceptual PlayWorld pedagogical characteristics (Fleer, 2022). To guide their decisions and assist with their planning they used the template found on Fleer’s Conceptual PlayWorld website .

Together, they identified a discrete space in the garden for an imaginary billabong where the story and new problems could be played out.

They agreed that the refrain from Wombat Stew would signal entering and exiting the Conceptual PlayWorld, so Charlotte set about recording this for the children.

The problems to be solved would be two-fold; first, they would follow the story elements to rescue the wombat, prompting the new problem of how to keep Wombat safe and well, with strong connections to the natural world and ecosystems for food and habitat.

Regarding play roles, Charlotte and Yuwen agreed to participate as play partners, most often equally present in the imaginary play space, trying to help Wombat stay safe and well. However, outside of this, they will act as models and guides, facilitating children’s learning of STEM and literacy concepts.

Figure 7.1

Charlotte and Yuwen are working together to plan the Wombat Stew Conceptual PlayWorld

Implementing the Conceptual PlayWorld and Amplifying Literacy

The following sections highlight how Yuwen and Charlotte implemented a Conceptual PlayWorld using Wombat Stew to intentionally engage children in language and literacy learning. Each instructional context below describes the carefully organised ways literacy concepts were advanced. Importantly, these occurred within the STEM problem-based play setting.

Book Reading

The text Wombat Stew was read a number of times throughout the Conceptual PlayWorld, with the children becoming more familiar with the text with each reading. Reading occurred with the whole group and on other occasions with small groups of children who requested to have the text reread. The book was available for the children to read independently. Frequent reading fostered familiarity with the text and created opportunities for the children to actively contribute to the reading process, joining in as the refrain ‘Wombat Stew, Wombat Stew’ was repeated. The children could see themselves as readers, prompting positive attitudes and a sense of achievement as they were apprenticed into a community of readers.

Figure 7.2

Child reading Wombat Stew

With familiarity with the text increasing with each reading, Charlotte engaged the children in shared reading, inviting their participation in conversations about, around and beyond the text (Gonzalez et al. 2014). Children were asked to predict the next animal and what they would contribute to the Wombat stew. They were also invited to imagine other animals that could be included in the story and what else could be added to the stew. Questions such as ‘What will the dingo do now?’ and ‘Will he enjoy the stew?’ created opportunities for children to produce language at an appropriate linguistic level while promoting conceptual challenge as new ideas were explored (Rowe & Snow, 2019).

A similar conversational style was used as word meanings were reinforced or introduced. Within the meaningful context of story reading, Charlotte described a ‘billabong’ as a pool of water in the bush, with the ‘bank’ at the water’s edge. Children were encouraged to ‘amble’ like a platypus and arch their necks ‘gracefully’ like the emu.

Charlotte also engaged the children in playful word interactions to stress the rhyme in the text. They repeated ‘goey’ and ‘chewy’ and enjoyed finding and inventing new words that followed the same rhyming pattern. On other occasions, Charlotte paused her reading inviting the children to build on the rhyming sequence and complete the text ‘crunchy, munchy…for my lunchy’ and ‘hot and spicy, oh so…nicey’.

The Wombat Stew text was not the only opportunity for children to develop understandings of reading. The Conceptual PlayWorld included signs such as ‘This way to the billabong’ as environmental print. The message received from the wombat requesting the children’s help was also prepared as an enlarged text, with this read with and by the children.

Practice Reflection 7.2: Working with a book you have selected, plan a series of prompts to invite children into shared reading. Your interactions should engage the children as active partners, focusing on the characters, the sequence of events and the language features of the text.

Modelled Writing

From her review of the research literature, Charlotte was aware of the importance of engaging children in drawing and writing experiences and was keen to involve the children as early writers. Modelled writing was selected as, through this approach, Charlotte could demonstrate the conventions and discourse patterns of written texts. While mindful this also needed to connect to and advance children’s play.

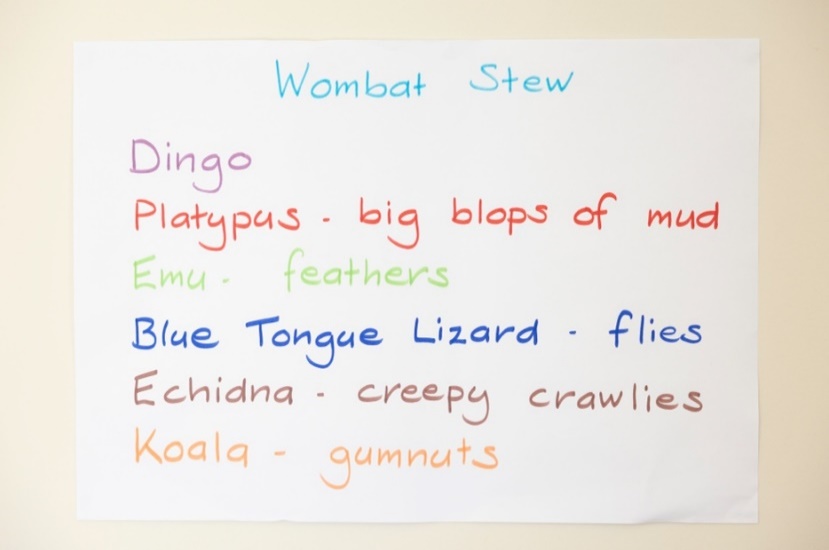

Yuwen and Charlotte planned for the children to role-play the story the first time they entered the PlayWorld. This involved choosing an animal character as they entered the play space and leaving a ‘stew’ by the billabong for the dingo so the wombat would be safe. To support the play, Charlotte decided to list the characters from the book and record what each animal added to the stew. As the list was created, the children could recall the animals, demonstrating their understanding of the sequence of events. Charlotte also found opportunities to draw the children’s attention to early print concepts, such as the left-to-right serial order of text and their knowledge of the alphabetic principle of matching letters and sounds.

The children eagerly contributed to the writing process, and Charlotte fostered knowledge of letters in two ways. She asked the children to spell words by reading from the list (what letters can you see in dingo?). She asked the children to suggest letters that can be used to record the names of the animals (what letters do I need to write emu?). Once composed, the list served as a prompt for the children’s role-play and became a reference point for children’s engagement in the Conceptual PlayWorld. By drawing children’s attention to specific features of the text, including, in this case, spelling, letter formation and letter/sound relationships, they gained a greater understanding of writing and what’s required of writers.

Figure 7.3

Wombat Stew character list

Figure 7.4

Children adding leaves and bugs to the stew

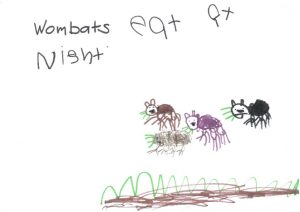

The children were also encouraged to document their thoughts, feelings and insights after each Conceptual PlayWorld experience. This often occurred through the children’s drawings and then talking about their ideas. Charlotte and Yuwen recorded the text for the children, following the Draw, Talk, Write and Share protocol (Mackenzie, 2022). In this way, they assisted the children in creating a permanent record of their imaginative play and learning. As the educators transcribed children’s thoughts, they were helping children to bridge the gap between oral language and printed text. These texts communicated the children’s ideas to a broader audience, capturing the depth and breadth of their thinking, which they would be unable to share if constrained by their own writing abilities (Halliday, 2016).

Practice Reflection 7.3 Read Noella MacKenzies‘ blog to learn more about the Draw, Talk, Write (and share) process and consider how this can supplement children’s learning as they engage in a Conceptual PlayWorld. Record your answers in your Fleer’s Conceptual Playworld thinking book.

Drawing and Early Writing

Beyond modelling, Yuwen and Charlotte were keen for the children to see themselves as writers, so they created occasions where writing was promoted as a social, shared experience. The children co-constructed texts with the teachers, working together to produce texts. They were also encouraged to appropriate the skills Yuwen and Charlotte modelled to produce texts independently, making conscious decisions to apply or approximate the understanding of print demonstrated to new situations.

After rescuing the wombat, Yuwen and Charlotte assisted the children to learn more about what wombats need for survival. Together, they accessed various books and websites. The knowledge gleaned from these texts was collated on a large chart. Children’s drawings and labels were pasted on the chart under the following headings:

Habitat – Where wombats live

Diet – What wombats eat

Activities – What wombats do

Figure 7.5

Child’s illustration with writing ‘Wombats eat at night‘

Figure 7.6

Child’s illustration with writing ‘Wombats eat grass’.

The letter received from Wombat that stated he was hungry and asking if the children could make a wombat stew for him to eat became the stimulus for the children to create and document a new recipe. This consisted of the children’s drawings and text, with the stew left by the billabong for the wombat to enjoy when he woke that evening.

Practice Reflection 7.4: What other opportunities can you think of to engage the children in drawing, mark-making and writing in the Wombat Stew PlayWorld? Record your thoughts in your personalised Fleer’s Conceptual PlayWorld thinking book.

Conclusion

The Conceptual PlayWorld that Charlotte planned and implemented enabled her to learn more about supporting children’s literacy learning through play. Reading to children continued to expose children to the complexities of written language. As she engaged children in a range of drawing and writing activities, working and problem-solving together to construct texts jointly, the children could see themselves as writers.

Practice Reflection 7.5: In your Fleer’s Conceptual PlayWorld thinking book, record the literacy learning opportunities the children experienced in the Wombat Stew Conceptual PlayWorld and the understandings about reading and writing that were advanced.

Return to the text you selected for linguistic analysis and design a Conceptual PlayWorld amplifying children’s literacy learning. List the opportunities for reading and writing to, with and by children within the context of STEM learning.

To find out more about Fleer’s Conceptual PlayWorld read the research on the Conceptual PlayLab website.

References

Australian Government Department of Education [AGDE] (2022). Belonging, being and becoming: The early years learning framework for Australia (V2.0). Australian Government Department of Education for the Ministerial Council.

Compton-Lilly, C. (2014). The development of writing habitus: A ten-year case study of a young writer. Written Communication, 31(4), 371-403.

Dickinson, D. K., Griffith, J. A., Golinkoff, R. M. & Hirsh-Pasek, K. (2012.) How reading books fosters language development around the world. Child Development Research, 2012, Article ID 602807, https://doi/10.1155/2012/602807

Dyson, A. H. (1999). Writing (Dallas) cowboys: A dialogic perspective on the ‘What did I write?’ question. In J. S. Gaffney & B. J. Askew (Eds.), Stirring the waters: The influence of Marie Clay (pp. 127–148). Heinemann.

Fleer. M. (2022). Balancing play and science learning – developing children’s scientific learning in the classroom through imaginary play. Journal of Emergent Science, (22), 13.

Gonzalez, J. E., Pollard-Durodola, S., Simmons, D. C., Taylor, A. B., Davis, M. J., Fogarty, M., & Simmons, L. (2014). Enhancing preschool children’s vocabulary: Effects of teacher talk before, during and after shared reading.Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 29(2), 214–226.

Halliday, M. A. K. (2016). Aspects of language and learning (J. J. Webster, Ed.). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-662-47821-9

Massey, S. L., Pence, K. L., Justice, L. M., & Bowles, R. P. (2008). Educators’ use of cognitively challenging questions in economically disadvantaged preschool classroom contexts. Early Education and Development, 19(2), 340–360.

Mackenzie, N. M. (2022). Finding out what they know and can do with DTWS. Practical literacy: the early and primary years, 27(1), 23-25.

Peterson, S. S., & Rajendram, S. (2019). Teacher-child and peer talk in collaborative writing and writing-mediated play: Primary classrooms in Northern Canada. Australian Journal of Language and Literacy, 42(1), 28–39.

Raban, B. (2018). Writing in the preschool years. In N. M. Mackenzie & J. A. Scull (Eds.), Understanding and supporting young writers from birth to 8 (pp. 50–70). Routledge.

Raban, B. & Scull, J. (2023). Literacy in the early years. In D. Pendergast & S. Garvis, (Eds.) Teaching early years: Rethinking curriculum, pedagogy and assessment (2nd Ed,). Allen & Unwin.

Rowe, M. L., & Snow, C. E. (2019). Analyzing input quality along three dimensions: Interactive, linguistic, and conceptual. Journal of Child Language, 47, 5–21. https://doi:10.1017/s0305000919000655

Scull J. & O’Grady K. (2022). Exploring urban place-based play as a stimulus for ‘Language in Action’ and ‘Language as Reflection’ in S. Stagg-Peterson & N. Friedrich (Eds.) Roles of place and play in young children’s oral and written language, (pp 167-184). University of Toronto Press.

Vaughan, M. K., & Lofts, P (1984). Wombat stew. Ashton Scholastic.

Attributions

“Figure 7.1.” by Adriana Alvarez, based on image by Anne Suryani, is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0

“Figure 7.2.” by Timothy Herbert is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0

“Figure 7.3.” by Timothy Herbert is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0

“Figure 7.4.” by Timothy Herbert is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0

“Figure 7.5.” by Timothy Herbert is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0

“Figure 7.6.” by Timothy Herbert is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0