Chapter 4: Conceptual PlayWorlds in dialogue across international contexts

Anne Suryani

Chapter goals

By reading and completing this chapter, you will be able to:

- understand the possibilities of using Fleer’s Conceptual PlayWorld across different settings and learn case studies from the Australian (see Chapter 1) and Indonesian contexts

- research how to integrate local contexts to benefit your teaching (e.g. being mindful of sociocultural aspects of your kindergarten setting, respecting local beliefs, values and practices; understanding the national early childhood curriculum, selecting local stories, and selecting important and localised concepts)

- develop strategies when applying intentional teaching in different contexts.

Introduction – Jumping into the imaginary situation

In Melbourne, Charlotte is looking at her diary. School holidays will begin in 2 months and she is very excited. She has been planning for months to visit her childhood friend, Sita, in Indonesia. They studied in the same primary and secondary schools in Clayton, a lovely multicultural suburb in southeast Melbourne. At that time, Sita’s parents were postgraduate students from Indonesia studying at Monash University. After her parents graduated, they went back to Indonesia. Sita and Charlotte have kept communicating over the years as they share the same hobbies and interests, enjoy reading and writing stories, and, most importantly, they love children and were keen to become kindergarten teachers. It has been 4 years since Sita returned to her home city of Yogyakarta.

Now, time is ticking! Charlotte feels that she needs to prepare for her visit to Yogyakarta. She has wished to visit this city since she heard from Sita that Yogyakarta is a beautiful place and a centre of classical Javanese fine arts and culture. Even more fascinating is that although Indonesia is a presidential republic, the government gave Yogyakarta a special region status as the only Indonesian royal city ruled by a monarchy.

Research reading 4.1: Explore the history of Yogyakarta special district, Indonesia.

From 1755 to 1945, the Yogyakarta Sultanate was a Javanese Islamic monarchy. After Indonesia gained independence in 1945, the Sultanate was transformed into the Special Region of Yogyakarta Province. In essence, Yogyakarta is the only province among all 38 Indonesian provinces led by a Sultan from 1755 until today.

What is the difference between a Sultan and a King? Both labels refer to a sovereign ruler with the power and authority to rule a country. However, a Sultan is a noble title with religious significance in Muslim countries, while the title of King tends to be more secular and is widely used in both Muslim and non-Muslim countries.

The current Sultan in Yogyakarta is Sri Sultan Hamengkubuwono X (read: Hamengkubuwono the tenth), also the Governor of Yogyakarta Special Region. While he holds a powerful political and spiritual position within the island of Java, he is also highly respected in the international community.

Research reading 4.2: Sultan of Yogyakarta: A feminist revolution in an ancient kingdom.

The changing role of women in Yogyakarta Sultanate

Javanese culture is traditionally a patriarchal one where the society expects men to play public-facing roles while women stay at home. This often translates to men enjoying superior public positions. In contrast, women were often given domestic roles that positioned them in a publicly inferior position.

Despite this, Sultan Hamengkubuwono X wishes to modernise the royal system by enacting a number of reforms. His stance is one of respect for women, and he values their position as equal to men. The Sultan married Gusti Kanjeng Ratu Hemas, and they have 5 daughters: Crown Princess Mangkubumi, Princess Condrokirono, Princess Maduretno, Princess Hayu and Princess Bendoro. All the children were sent to study in either Europe, the United States or Australia. Once they returned to Yogyakarta, they were all given various leadership positions in the palace.

There are at least 3 important decisions the Sultan has made since he came to power in relation to gender equality. First, the Sultan changed his title to be gender neutral. Second, he announced his eldest daughter as his successor.

The third decision is considered controversial yet one he highly values. In the past, it was common practice for a Sultan to have more than one wife. Given that all of the current Sultan’s children are female, this is even more important within Javanese high society as they prefer that his heir be male. However, the Sultan has publicly declared that he will not practice polygamy.

Research reading 4.3: By reading this journal article, Gender politics in Yogyakarta Sultanate (Ratnawati, 2021), you will learn about the shift in the culture of the Yogyakarta Palace, from being patriarchal to promoting gender equality.

Planning a Fleer’s Conceptual PlayWorld in a localised context: What to prepare?

Charlotte has bought return flight tickets from Melbourne to Yogyakarta. She has read information about Yogyakarta and has a list of places to visit. Has she finished with her preparation?

Of course not. One important thing on her bucket list is to share Fleer’s Conceptual PlayWorld model with Sita and practice it together in the kindergarten where Sita is currently teaching.

Practice reflection 4.1. Go back to Chapter 1 and review the 5 characteristics of Fleer’s Conceptual PlayWorld. Record your notes in your Fleer’s Conceptual Playworld thinking book.

Charlotte starts thinking about the 5 characteristics of Fleer’s Conceptual PlayWorld. Before she begins, she needs to know more about Indonesia’s contexts in general and specifically Indonesian early childhood education. What do Indonesian children learn and how do they play? How do local kindergartens operate in Yogyakarta? So many questions to explore.

Understanding the educational system

Charlotte begins browsing websites about the Indonesian educational system. The Republic of Indonesia is the fourth most populous country in the world, with 277 million people living there. Although it is officially secular, religion is an important aspect in people’s lives. Approximately 87% of Indonesians, or 241 million people, identify themselves as Muslims, making Indonesia the largest Muslim-majority country in the world (Ministry of Religious Affairs of Indonesia, 2022).

Compulsory education in Indonesia starts at primary (7–12 years old), followed by junior secondary (13–15 years old), and senior secondary (16–18 years old) levels. Enrolment in pre-primary or early childhood (3–6 years old) is optional. Two ministries oversee the education system. The Ministry of Education, Culture, Research and Technology (MoECRT) manage public and private schools, which are predominantly decentralised. The Ministry of Religious Affairs (MoRA) manage Islamic public and private madrasahs, which are mainly centralised. Around 80% of primary and secondary schools are managed by MoECRT and the remaining schools are madrasahs managed by MoRA.

Practice reflection 4.2: Do you remember the Australian education system? Compare it to the Indonesian education system – did you find any similarities and differences? Record your thoughts in your personalised Fleer’s Conceptual PlayWorld thinking book.

Now that Charlotte understands Indonesian education, she wants to know more about the early childhood setting. She endeavours to spend the next few days learning more about the Indonesian approach to early childhood education.

Understanding early childhood in Indonesia

The Indonesian government recognised the importance of early childhood education in 2001 when they established the Directorate of Early Childhood Education under the Ministry of Education and Culture (note. The Ministry of Education and Culture and the Ministry of Research and Technology were merged in 2021 and renamed as The Ministry of Education, Culture, Research and Technology [MoECRT]).

As with other countries, the MoECRT works with other government agencies to improve the quality of early childhood. The Ministry of Social Welfare, the Ministry of Health, and the Ministry of Women’s Empowerment also oversee Indonesian early childhood education and care. To add a layer of complexity, Indonesia’s strong religious culture means that the MoRA manages religious-based Early Childhood Education (ECE) centres, while the MoECRT manages non-religious-based ECE centres.

There are different types of ECE centres in Indonesia. They can be formal or nonformal, and public or privately funded. One of the many criteria used to define formal vs nonformal ECE centres was the qualification of teachers working there (UNESCO, 2004, 2005). Those teaching in a formal ECE centre must have a teaching qualification from a university. Meanwhile, nonformal ECE centres do not have such requirements for their teachers.

In 2020, only 2% of the 202,991 ECE centres in the country were public and funded by the government (Adriany, 2022). Thus, the majority of ECE centres are run by private organisations.

Figure 4.1.

Charlotte and a map of Indonesia

Another interesting classification of Indonesian ECE centres is the name of services based on their activities. The ECE centres can be categorised as kindergarten (a formal centre for 4–6-year-old children), playgroup (a nonformal centre for 2–4-year-old children, although in some areas it may include 4–6-year-old children), day-care (a centre for 0–2-year olds), and nonformal early childhood education (which are often run by volunteers in villages/rural areas).

Research reading 4.4: You can explore more about ECE in Indonesia (Adriany, 2022, pp. 2–6)

Early childhood curriculum

The ECE curriculum in Indonesia is ‘highly standardised and centralised’ (Adriany, 2022, p. 9). The ECE National Curriculum classifies children’s development into 6 domains: physical, social-emotional, language, art, cognitive, and religious development (MoEC, 2014). It addresses core competencies based on children’s age groups, from birth to 2 years old, 2–4 years old, and 4–6 years old.

Charlotte finds too much information at this stage. She decides she needs to focus on kindergartens because Sita teaches at a local kindergarten in Yogyakarta. Charlotte reflects on all her reading so far and tries to find more information on Indonesian kindergartens.

In the kindergarten setting, children are expected to develop 4 core competencies: spiritual, social, knowledge, and skill competencies (Adriany, 2022).

- First, the spiritual competencies expect children to believe in God and His creations, and be able to appreciate themselves, other people, and the environment as an expression of gratitude to God.

- Second, the social competencies consist of 14 fundamental competencies, such as having a healthy lifestyle, showing creativity, showing appreciative behaviour and tolerance to others, showing honesty, and being humble and polite to parents, teachers and friends.

- Third, the knowledge competencies comprise 15 fundamental competencies, such as acknowledging daily prayer, having good morals and behaviour, acknowledging the environment (e.g. animals, plants, climate, land, water, and rocks), knowing simple technology (e.g. household items, mechanic utensils), understanding receptive and expressive languages, as well as knowing their emotions and others.

- Fourth, the skill competencies consist of 15 components, such as observing daily prayer with adults’ guidance, demonstrating good moral behaviour, being able to solve daily problems creatively, demonstrating receptive language, understanding expressive language, and demonstrating preliteracy skills.

Research reading 4.5: See Table 5, page 11, for a complete list of competencies for kindergarten in the Indonesian ECE curriculum (Adriany, 2022)

Practice reflection 4.3: Now you that know the 4 core competencies intended for kindergarten children in the Indonesian ECE curriculum, read the 5 Learning Outcomes in the Early Years Learning Framework for Australia V2.0 (ACECQA, 2023, p. 29). What did you find most interesting between the 2 policy documents? Record your thoughts in your personalised Fleer’s Conceptual PlayWorld thinking book.

Figure 4.2.

Charlotte standing at the playground and thinking about what to do next.

Planning a Conceptual PlayWorld in the Indonesian context

Fleer’s Conceptual PlayWorld model was developed in the Australian context (see Chapter 1 and the Conceptual PlayWorld website). We know that Charlotte will implement Conceptual PlayWorlds with Sita in a local kindergarten in Yogyakarta. She has read about the local culture in Yogyakarta, the province where Sita’s kindergarten is located. She has also prepared herself with some knowledge about the Indonesian education system, early childhood setting, and national ECE curriculum. Now, it is time to get into the 5 characteristics of Fleer’s Conceptual PlayWorld.

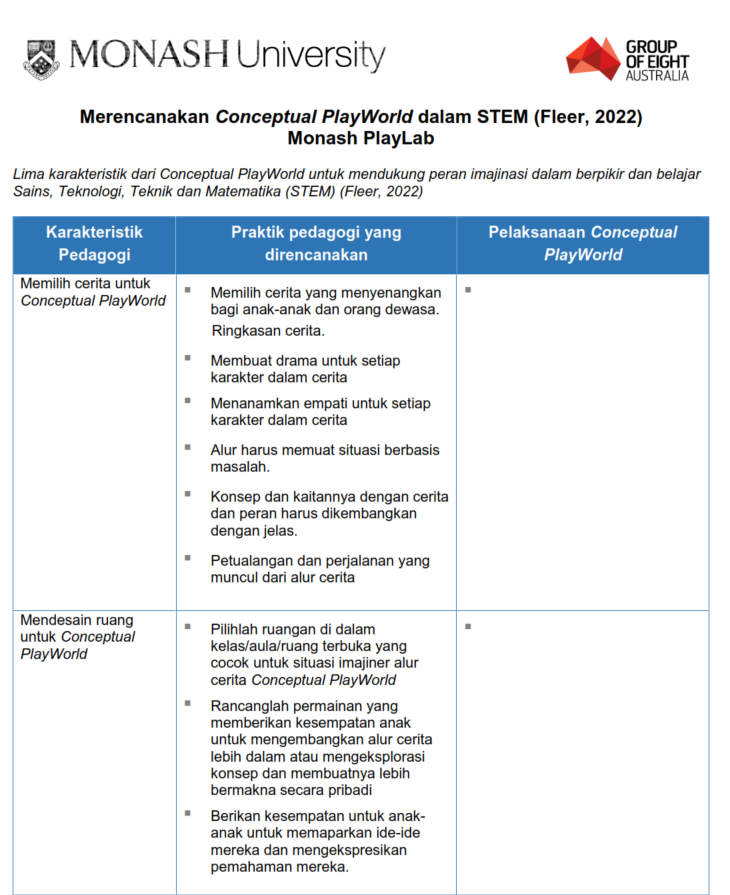

Figure 4.3.

Fleer’s Conceptual PlayWorld planning proforma in Bahasa Indonesia

Practice reflection 4.4: Fleer’s Conceptual PlayWorld planning proforma has been translated into different languages: Bahasa Indonesia, Chinese, Japanese, Vietnamese, Laos, Arabic, and many more. You can download these planning proformas from the Conceptual PlayWorlds website.

Help Charlotte think about which aspects of the 5 characteristics of Fleer’s Conceptual PlayWorld need to be modified in different cultural contexts. Refer to Table 1.1 in Chapter 1.

The big day

Charlotte feels ready to practice her Conceptual PlayWorld with Sita in Yogyakarta. She has read extensively on the background of ECE in Indonesia, selected a local storybook and completed a planning proforma.

Charlotte can’t wait to visit Yogyakarta and implement a Conceptual PlayWorld with Sita. She notes that during her preparations, it is important to:

- learn about cultural values, beliefs and practices of both settings

- explore the target country’s education system and national curriculum

- understand the target country’s early childhood curriculum, including any expected learning outcomes or core competencies

- try using local sustainable eco-friendly resources to support your Conceptual PlayWorld

Conclusion

This chapter discusses several important concepts to consider when implementing Conceptual PlayWorlds in different sociocultural settings. We suggest student teachers be mindful of the local values, beliefs and practices when teaching in culturally diverse contexts. Understanding the national curriculum and education system would be helpful, particularly in early childhood settings. Student teachers are encouraged to integrate local knowledge into their teaching practice. By developing these strategies, student teachers can use evidence to contextualise the Conceptual PlayWorld model. This will enable them to successfully implement a Conceptual PlayWorld that aligns with country-specific curriculum and cultural expectations.

To find out more about Fleer’s Conceptual PlayWorld read the research on the Conceptual PlayLab website.

References

Adriany, V. (2022). Early Childhood Education in Indonesia. In: L.P. Symaco, & M. Hayden (eds), International Handbook on Education in South East Asia. Springer International Handbooks of Education. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-16-8136-3_28-1

Australian Government Department of Education [AGDE] (2022). Belonging, being and becoming: The early years learning framework for Australia (V2.0). Australian Government Department of Education for the Ministerial Council. https://www.acecqa.gov.au/sites/default/files/2023-01/EYLF-2022-V2.0.pdf

BBC News (2018, 1 June). Sultan of Yogyakarta: A feminist revolution in an ancient kingdom. Retrieved September 3, 2023, from https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-43806210

Encyclopaedia Britannica. (n.d.) Yogyakarta. Retrieved September 3, 2023, from https://www.britannica.com/place/Yogyakarta-special-district-Indonesia

Ministry of Religious Affairs of Indonesia. (2022). Number of people by religious affiliations. https://satudata.kemenag.go.id/dataset/detail/jumlah-penduduk-menurut-agama

Ministry of Education and Culture Republic of Indonesia. (2014). 2013 Curriculum of early childhood education, Vol 146. Ministry of Education and Culture Republic of Indonesia, Jakarta

Ratnawati, & Santoso, P. (2021). Gender politics of Sultan Hamengkubuwono X in the succession of Yogyakarta palace. Cogent Social Sciences, 7(1), 1976966. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2021.1976966

Suryani, A., Tirtowalujo, I. & Masalam, H. (Eds). Preparing Indonesian Youth: A Review of Educational Research. Brill. https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004436459_001

UNICEF. (2016). Transforming the lives of Indonesian children with Early Childhood Education. https://www.unicef.org/stories/transforming-lives-indonesian-children-early-childhood-education

UNESCO. (2004). The background report of Indonesia. Retrieved September 5, 2023, from https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000138849

UNESCO. (2005). Policy review report: Early childhood care and education in Indonesia. Retrieved September 5, 2023, from https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000138522

Attributions

“Figure 4.1.” by Adriana Alvarez, based on an image by Anne Suryani, is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0

“Figure 4.2.” by Adriana Alvarez, based on an image by Anne Suryani, is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0

“Figure 4.3.” by Marilyn Fleer is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0