Chapter 1: Overview of a Conceptual PlayWorld

Marilyn Fleer

Chapter Goals

By reading and exploring the content of this chapter, you will learn:

- what is Fleer’s Conceptual PlayWorld

- how to plan a Conceptual PlayWorld

- how to set up a pop-up Conceptual PlayWorld.

Introduction – Jumping into the imaginary situation

You are about to enter an imaginary world of an early childhood centre (later, you will be in a primary classroom). In this world, you will meet Charlotte, a student teacher, and Yuwen, an experienced teacher. They are co-teaching. However, a problem has arisen.

You meet Charlotte crying outside of the classroom. Sobbing, she says, ‘I can’t go back in’. Charlotte appears to be experiencing a crisis. She needs your help (see Figure 1).

Crisis is a scientific concept from cultural-historical theory that captures a moment when someone is experiencing some kind of drama or contradiction that propels them forward in their development as they consciously experience the situation emotionally and cognitively.

In this book, you will encounter many scenarios like this. Your role is to work through a range of solutions to help Charlotte and Yuwen as they plan and implement different kinds of Conceptual PlayWorlds.

Figure 1.1.

Meeting Charlotte

Each chapter of this book will prompt you to research and solve a problem associated with Charlotte’s implementation of Fleer’s Conceptual PlayWorld. There are many scenarios to work through and various solutions to assist Charlotte. Your scenario menu is:

Chapter 2: Conceptual PlayWorld in support of equity and access

Chapter 3: Play role, drama and learning concepts in a Conceptual PlayWorld

Chapter 4: Conceptual PlayWorld in dialogue across international contexts

Chapter 5: Capturing learning: Assessment in a Conceptual PlayWorld

Chapter 6: Mathematics in a Conceptual PlayWorld

Chapter 7: Conceptual PlayWorld fostering language and literacy learning

Chapter 8: Using Conceptual PlayWorld to build wellbeing

Chapter 9: Conceptual PlayWorld for families: Why play works for teaching STEM in the home setting

Chapter 10: Conceptual PlayWorld to study the structuring of time into days, weeks and months

You can navigate the menu in whatever way supports you with resolving the challenges Charlotte meets. As you review each chapter, record your thoughts in your personalised Fleer's Conceptual PlayWorld thinking book (see booklet in Appendix A). The general questions are:

- What is the problem that Charlotte is thinking about or experiencing?

- What is one key idea you gained from reading the narrative or viewing the material that you believe could help solve Charlotte’s problem?

- What are you curious about? Which chapter in this book could help you?

In some of the chapters are additional questions. You can respond to those questions in your Fleer's Conceptual PlayWorld thinking book .

However, before you launch into the different scenarios across the chapters, listen to Charlotte’s story and discover why she is sobbing and ‘can’t go back' into the classroom.

Charlotte’s story: practical life is full of challenges – Meeting the problem

Charlotte grew up in a regional community on a farm. Her family are immigrants. Charlotte was the first in her family to go to university. Moving from the country to the city for university was the first big challenge she met. However, planning to teach in a preschool was her second. She had never stepped inside a preschool before. She had no personal experience of preschool education herself. Charlotte was very excited to be on her first placement.

Charlotte spent much time planning for her teaching placement. The university had asked her to plan one activity each day and suggested the first might begin by reading a children’s book to a small group. She chose Rosie’s Walk (Hutchins, 1987). It suited her, as she felt comfortable with the plot; it connected with her own rural life. She made plans and checked these with her supervising teacher, Yuwen.

She prepared the scene for reading the book to add excitement for the children. On the weekend, she drove to a farm and bought 3 bales of hay – this would make good seating and define the space where she would read the book. She placed a painter’s sheet on the floor to protect the carpet. She also prepared a basket of real eggs – the idea was to collect the eggs Rosie had laid. They would be hidden in the hay for the children to find. The reading would be followed by using the eggs to make pikelets. This also connected nicely with the flour mill in the story.

On the first day of her practicum, she came into the preschool early and full of enthusiasm. She showed her detailed plans to Yuwen, placed the sheet over the carpet as discussed and built a defined reading area with the hay bales. She opened one bale of hay, which she scattered evenly over the floor. She then hid the eggs in the hay. Her cooking equipment was close by, ready to be used for her follow-up activity. Her PlayWorld transition would be as hungry chickens leaving the farm. Charlotte felt satisfied with the visual effect.

Practice reflection 1.1: Do you see any potential problems? Can you guess what happened? Record your thoughts in your personalised Fleer's Conceptual PlayWorld thinking book. Note Charlotte’s planning. Consider Charlotte’s first experience working with a 'whole group' of children – not just a small group, as advised by the university.

Fast forward to mid-way through the story reading. The children are throwing hay everywhere. One child reacts to the hay, and Yuwen quickly removes the child and calls the family, leaving Charlotte to deal with the situation arising as the children shower each other in hay.

Another child sits on one of the eggs – not knowing the eggs are hidden in the hay. She is covered in yoke and screaming.

No cooking took place that day.

Research reading 1.1: Read Chapter 7 to learn more about student wellbeing and consider the links to teacher wellbeing.

Practice reflection 1.2: What would you do to restore the situation? What went wrong despite Charlotte's thoughtful planning? Record your thoughts in your personalised Fleer's Conceptual PlayWorld thinking book.

As you read on, your role will be to help Charlotte as she solves the challenge of planning and implementing a Conceptual PlayWorld for the first time. Consider the following:

Charlotte put great effort into planning and designing the reading space. Yuwen responded positively to Charlotte’s enthusiasm and creativity. She had never had a student teacher go to so much trouble to read a story. The crying did stop (see Figure 1.2).

Figure 1.2.

Charlotte studies how to plan Fleer’s Conceptual PlayWorld

Yuwen introduced Charlotte to a model of play and learning called Fleer’s Conceptual PlayWorld.

What is Fleer’s Conceptual PlayWorld?

An overview of a pop-up Conceptual Playworld based on Rosie’s Walk is demonstrated in the video below. This video also showcases all of the characteristics in practice.

Table 1.1 gives a brief overview of the 5 characteristics of Fleer’s Conceptual PlayWorld.

Table 1.1. The 5 characteristics of Fleer’s Conceptual PlayWorld

| Characteristic | Description |

|---|---|

| 1. Designing a Conceptual PlayWorld space | Finding a space in the main room or outside suitable for an imaginary Conceptual PlayWorld of the story. |

| 2. Entering and exiting the Conceptual PlayWorld space | Plan a routine for the whole group to enter and exit the Conceptual PlayWorld of the story, where all the children are in the same imaginary situation. |

| 3. Planning the play inquiry or problem scenario |

|

| 4. Planning educator interactions to build conceptual learning in role |

|

| 5. Planning educator interactions to build conceptual learning in role |

|

Planning a Conceptual PlayWorld – Evidence-informed model

Yuwen suggested a set of resources to help Charlotte to plan her own Conceptual PlayWorld.

- Yuwen was introduced to Charlotte Fleer's Conceptual PlayWorld website during their debrief.

- Charlotte then looked at the planning resources on the website to learn how to create a Conceptual PlayWorld.

- Appendix B is an example of a planning proforma designed for infants and toddlers, containing detailed content for each characteristic that could help Charlotte in the future with planning a Conceptual PlayWorld for very young children.

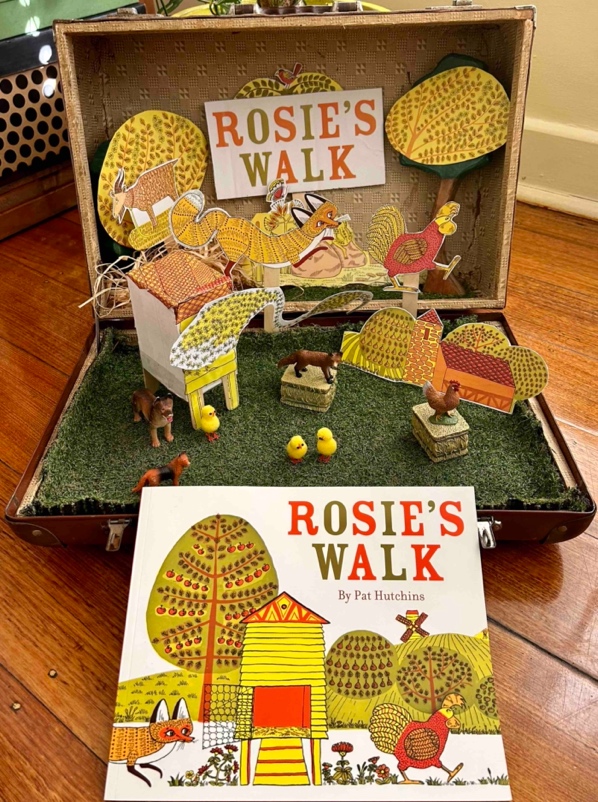

- Yuwen also showed Charlotte a portable pop-up of Rosie’s Walk as a resource to support her practicum placements in the future. Using the suitcase of the story props will mean less preparation for her (see Figure 1.3).

Figure 1.3.

A portable pop-up of Fleer’s Conceptual PlayWorld of Rosie’s Walk

Practice reflection 1.3: In your Fleer's Conceptual PlayWorld thinking book, compare what you see in the overview video of practice to that of Charlotte’s story of using the same book. Critically view the video, identify some pedagogical characteristics you are curious about, and start a discussion about it in our private Facebook for Conceptual PlayWorlds.

Research reading 1.2: You can also find other ideas about how to design interesting spaces for a Conceptual PlayWorld in Chapter 9.

Research reading 1.3: Select and read the research papers that are the foundation for Fleer's Conceptual PlayWorld on Monash University’s Conceptual PlayWorld webpage. This evidence-informed model is used across Australia and internationally (see Chapter 4 and Chapter 10).

Dramatic story, rather than dramatic activity

Yuwen is sitting outside of the classroom, still comforting Charlotte. She explains to Charlotte that she has selected the perfect book to read to the children. The story is dramatic and suspenseful – as Rosie the hen walks about the farmyard, oblivious to the fox who tries at every turn of the page to catch and eat her. The children experience the suspense as the audience viewing the drama in the picture book. It is highly motivating for them. They build empathy for the characters in the story. They want to keep Rosie safe and don’t want her eaten. Some want to be bees so they can sting the fox, while others playfully identify with the fox. Yuwen explains that suspense and drama are important when planning a Conceptual PlayWorld. Charlotte looks surprised but is listening intently.

Practice reflection 1.4: Find another children’s book that you believe is full of drama and would help children build empathy with the characters in the story. Record your ideas in your Record your thoughts in your personalised Fleer's Conceptual PlayWorld thinking book. Watch the video ‘Selecting a dramatic story’ for ideas to support your reflections.

Planning how to jump into the story

Charlotte was disappointed by the outcome of her carefully planned activity and engaging reading area. Yuwen highlighted an important thing that Charlotte did - she had considered the imaginary situation of the story. She had turned the preschool into Rosie’s farm. The props made it easier for the children to imagine being on the farm – something outside the children’s city experience of everyday life.

Yuwen: The scene you set up made it easy for the children to jump into the imaginary world of Rosie’s farm.

Charlotte: But it was chaos – hay everywhere!

Yuwen: You were thinking about developing the children’s imagination by being on the farm. I noticed in your planning that you had carefully thought about a routine to go from the farm to the cooking area. This is also an important part of planning a Conceptual PlayWorld. You planned the exit by being hungry chickens clucking over to the cooking area to make pikelets. You could do the same for entering the Conceptual PlayWorld space you designed. The children could be chickens entering the imaginary space, but they could also be other characters from the book. The children already know the story, and when they see a sign on the preschool door that reads ‘Rosie’s Farm’ they can enter the imaginary world in character. Importantly, both the children and teachers enter in character as a group of foxes, a group of bees, and a group of chickens.

Practice reflection 1.5: How would you design the imaginary space for the book you previously selected? Record your thoughts in your personalised Fleer's Conceptual PlayWorld thinking book.

Watch this video about how to plan using the storybook of Rosie's Walk, but framed to design a space for Fleer’s Conceptual PlayWorld with minimal props.

Then watch this video of how to plan the entry and exit into Fleer’s Conceptual PlayWorld.

Practice reflection 1.6: Brainstorm a range of entry and exit routines for Rosie’s Walk and your chosen book. Some examples from the research include stepping into a huge basket and pretending to go up in a hot air balloon (Lindqvist, 1995) or going back in time through a portal (outdoor equipment) with the routine of counting down from 10 to zero in the time machine. Other examples can be found in the Conceptual PlayLab Working papers.

Authentic problem

Yuwen asks Charlotte if she had used the planning proforma, what kind of concept the book could offer the children, and what might be the authentic problem they could solve together.

Charlotte: I thought Rosie was walking all over the farm in the story. I had thought that we would imagine going all around the farm as part of finding the eggs. We would go over the haystack – which we had plenty of here today. The children would also go around the pond, and they would go under the flour mill. That’s why we were going to make pikelets – to use the flour from the flour mill – collecting it in the imaginary situation, and then using it in an actual situation of cooking for snack time.’

Practice reflection 1.7: What are the concepts Charlotte is explaining? Record your thoughts in your personalised Fleer's Conceptual PlayWorld thinking book. Check your curriculum document now in relation to the concepts.

Watch this video about planning the authentic problem that the children will want to solve with concepts from the curriculum. How do they align?

Yuwen discusses with Charlotte the prepositional language foregrounded in the book, which could be brought out in the imaginary situation as children jump into the story of Rosie’s Walk and become Rosie walking around the farm.

Yuwen: What is special about Fleer’s Conceptual PlayWorld is that when you take the child’s perspective, you don’t just ‘teach the concept’ but rather you carefully plan what concept is to be learned and then create motivating conditions where the children meet a problem that they want to solve. That is, the children want to help the characters from the book. They want to keep Rosie safe. Also, you would have seen in the video that the teacher set up an additional problem – Rosie’s cousin wants to visit but is lost. The children need to help her by making maps. This happens outside of the imaginary situation after they return from visiting the farm. But it could also happen inside the imaginary situation.

Charlotte: So the children learn the concepts to help Rosie?

Yuwen: Yes, the concepts serve the children’s play. The children take the map back into the Conceptual PlayWorld to help Rosie’s cousin find the farm.

Charlotte: Did all of that happen in just one day?

Yuwen: It can happen all in one day. It is called a pop-up Conceptual PlayWorld. The imaginary situation is just a pop-up imaginary play after reading the story. However, a Conceptual PlayWorld can also take much longer, even weeks or months – just by adding more problems to solve or reading a chapter each week from a much longer book. You can introduce new problems to a simple picture book, like Rosie’s Walk. For example, by returning to Rosie’s farm, the children find that the pond has dried up and the animals are thirsty. Bringing civil engineering principles to pipe water in and help solve the problem.

Charlotte: But how is this high level of engineering thinking possible with such young children?

Yuwen: Most will think this is not possible for such young children, but research now shows we underestimate what young minds can engage with (See the Conceptual Playlab working papers for more information).

Imagine children looking at the water flowing down a pipe in the sandpit. They adjust the pipe level to channel the water into places they want. We can see them doing this now in their play in the sandpit. However, for engineering, you can ask them to look for any blockages and make adjustments to the water flow; you can introduce a spirit level so they can physically see how the gradient has changed, and they can then adjust the pipes accordingly, and with more precision and understanding; this is civil engineering at its very best for 3- and 4-year-old children.

Practice reflection 1.8: In planning your Conceptual PlayWorld of your chosen story, what will be the authentic problem? What concepts will act to serve the children’s play? How will the play deepen because your children bring more concepts into their play? Record your thoughts in your personalised Fleer's Conceptual PlayWorld thinking book.

By turning her planned creative ideas into a Conceptual PlayWorld, Charlotte can now see how she could plan for children's play and learning. She can be more focused on the concepts and what might be the authentic problem that the children want to help solve.

Research reading 1.4: Learn about the research into why concepts matter for Fleer’s Conceptual PlayWorld by reading Chapter 6 and gain further examples of mathematical learning. You can also find more on literacy concepts and their development in Fleer’s Conceptual PlayWorld in Chapter 7.

Being a play partner

Unlike other beliefs about children’s play, Fleer’s Conceptual PlayWorld works on the premise that the teacher changes her role from teacher to play partner. Yuwen explains to Charlotte that she can take on many roles. But she needs to be inside the imaginary play situation as a character from the story or an introduced character, such as,

- a wise owl (above position)

- a curious puppy (equal position)

- a helper rabbit (under position)

- someone who acts in unity with the child(ren), and together they role-play in the same character or family of characters, such being as a flying bat (e.g., teacher) with her babies clinging on (e.g., child/ren) as they go on adventures together (primordial we position).

Charlotte: But I am learning to be a teacher. How can I be a teacher and a play partner simultaneously? I already have problems with managing the children. Won’t this model of a Conceptual PlayWorld make the children even more chaotic if I am not controlling the situation?

Yuwen explains that all the research on the model confirms that because the children are so motivated to help solve the problem, the teacher can still manage the situation from inside the play and through their character role.

Yuwen: When you are the wise owl, you can be above the children giving advice. So, if something is going wrong, the wise owl can come in and say, ‘I have such a headache from all this noise. I cannot hear myself think. Did you know …’ If you want to introduce some key information, it can be delivered, like in the series of books about Harry Potter when the owls deliver messages or items to help the play along – like a new broom or a message about approaching danger that has to be avoided.

The teacher can also be in the under position with the children in the above position. Such as when the second teacher joins the children and asks what happened here. This could also be the principal if you were in a school. The children then recount their experiences and what they have learned to the second teacher (or principal).

Charlotte: That is a nice relationship – the teacher in the under position and the children in the above position. What a fantastic way to find out what the children know and can do. That must be such an authentic approach to assessment.

Yuwen: But wait, there’s more… The teacher can also be in an equal position. By being with the children they are solving the problem together.

Research reading 1.5: Find out more about authentic problems in Chapter 6 and see further examples and ideas.

Watch the video ‘Teacher as the play partner in Fleer’s Conceptual PlayWorld’ to see how this can happen.

Research reading 1.6: Chapter 6 presents research related to teacher positioning in play and learning. Read Chapter 3 on play pedagogy and the role of the educator in Fleer’s Conceptual PlayWorld.

Practice reflection 1.9: Look at all the responses you made in your Fleer'sConceptual PlayWorld thinking book while reading this chapter and consider if you are ready to plan a pop-up Conceptual PlayWorld.

How to set up a pop-up conceptual playworld

Fleer’s pop-up Conceptual PlayWorld is planned and implemented in one session. It takes place instead of group time and uses part of free choice time/tabletop activities. Your planning would follow the steps in Table 1.1 and involve gathering the children as you usually do for group time. You would use group time for reading the story. Rather than children self-selecting activities following group time, you would go as a whole group into the imaginary Conceptual PlayWorld using the routine you planned for entering into an imaginary situation. This would take about 15–20 minutes. After meeting the problem in the role-play of the storybook, you would exit the imaginary situation to solve the problem. The planned activities include you and the children researching and solving the problem you met in the Conceptual PlayWorld. This may take 15 minutes as children draw, create, or look at books/YouTube as part of their research. Then, you would re-enter the Conceptual PlayWorld to play out the solution. This would take about another 15 minutes. Your program for your pop-up Conceptual PlayWorld could look like this:

- Group time (read the story and invite children to be a character from the storybook).

- Enter the Conceptual PlayWorld space (jump into the story in character) using the planned routine.

- Pretend play of the story. Meet a problem to solve – helping the character.

- Exiting the Conceptual PlayWorld space using the planned routine.

- Researching to solve the problem so you can help the character from the book.

- Re-enter the Conceptual PlayWorld space (jump back into the story in character) using the planned routine and then, through your play, help the character.

- Exiting the Conceptual PlayWorld space using the planned routine.

The play problem could also be set up when reading the storybook to the children – such as when a letter falls out of the book. The letter could be from the main character asking for help. Alternatively, the children could find the letter with the problem in the imaginary Conceptual PlayWorld.

Conclusion

In this chapter you met Charlotte and Yuwen as they worked through Charlotte’s teaching placement crisis, transforming it into a Conceptual PlayWorld. She is now re-engaging with the children and thinking about how to plan and implement Fleer’s pop-up Conceptual PlayWorld of Rosie’s Walk.

Practice reflection 1.10: Before reading the next chapter, review the notes you made for each video link and summarise or list the characteristics of Fleer’s Conceptual PlayWorld for Rosie’s Walk. Record your thoughts in your personalised Fleer's Conceptual PlayWorld thinking book.

Practice reflection 1.11: Finalise your own Conceptual PlayWorld for your chosen book. You will return to your plans as you go through the adventures found in the different chapters of this book. Over time, you will deepen your understanding as you assist Charlotte.

Research reading 1.7: Find out more about Fleer’s Conceptual PlayWorlds in Chapter 10 to further support you with planning your own Conceptual PlayWorld as a student teacher.

References

Hutchins, P. (1987). Rosie’s walk. Scholastic.

Lindqvist, G. (1995). The aesthetics of play: A didactic study of play and culture in preschools. Almqvist & Wiksell International.

Attributions

"Figure 1.1. " by Adriana Alvarez, based on an image by Anne Suryani, is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0

"Figure 1.2." by Adriana Alvarez, based on an image by Anne Suryani, is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0

"Figure 1.3." by Monique Parkes is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0

Science, Technology, Engineering, Mathematics