45 Work, employment and industrial relations policy

David Peetz; Shalene Werth; and Susan Ressia

Key terms/names

associational power, Australian Building and Construction Commission (ABCC), Australian workplace agreements, awards, bargaining representatives, centralised wage determination, conciliation and arbitration, employment relationship, gender pay gap, inequality, multi-lateral rule making, penalty rates, Prices and Incomes Accord, pluralist, safety net, union density, unitarist, universal paid parental leave

The employment relationship – that between employer and employee – is at the heart of capitalism and a core issue for public policy.[1] Governments create rules, policies and institutions within which employees, their representatives, employers and their representatives, operate. The interest to governments when creating policy includes the form that bargaining takes, wage and employment levels, the nature and effects of contracting and the rights of workers – much of this boiling down to issues of power. In recent decades, major policy issues have included the federal Labor government’s Prices and Incomes Accords in the 1980s and 1990s, the Coalition government’s ‘WorkChoices’ legislation, the shift to enterprise bargaining, and developments in such areas as minimum wages and pay equity. In this chapter we outline the matters at stake, the players, the policy processes and some of the key issues.

What’s at stake?

Central to policy decisions is the political ideology of the decision maker, and the implications of that ideology for whose interests should prevail within the employment relationship. Put simply, is the priority for government the interests of business or the advancement of worker interests? Approaches to the management of labour may be described as being ‘unitarist’ or ‘pluralist’ and these concepts are manifested in policy and practice.

The imprecision of the employment relationship – the heart of capitalism

At the beginning of the employment relationship the worker agrees to sell their labour to the employer in the form of an ongoing market transaction. However, it is almost impossible for the contract of employment to specify everything that the employee does in their work. In the service sector, where measurement of employee output is harder, the imprecision of the employment relationship is especially high.

The power of capital and labour

The study of work and employment relations policy is also the study of power. The groups and individuals with power are those who benefit most from policy making. Public policy may also affect the power that various groups and individuals have.

The relative power of employers and unions at the workplace is not easy to measure. A pluralist approach ‘accepts the rights of employers, employees and unions to bargain over their separate interests’.[2] It also recognises that the conflict that occurs in the workplace is to be expected and managed. In a capitalist economy, governments who wish to advance the interests of workers tend to create policy from a pluralist perspective. Governments, seeking to implement a policy that protects business interests, often adopt a unitarist perspective. This assumes that employers and employees have the same objectives and any conflict that might occur in the employment relationship is unusual. Unitarist policies often do not support the existence of an independent umpire to provide arbitration of workplace disputes. Conservative or ‘right-wing’ approaches of the state to industrial relations are often associated with unitarist conceptions of this field. There are other perspectives on employment relations (e.g. radical, Marxist, postmodern or feminist approaches)[3] but these are analytical perspectives, sometimes also held by workers, but not by employers and rarely by government.

Governments, regardless of whether they espouse a unitarist or pluralist perspective, claim to be interested in improved economic outcomes. This is an objective that can appeal to everyone, and productivity growth, for example, affects the level of resources available to distribute to capital and labour. However, there is no agreement about how improved economic outcomes should be achieved, and this objective is often just a guise for realigning the balance of power in the workplace. Where policies, for example, support capital at the expense of labour, they are more likely to entrench inequality. With unions being formally tied to the Australian Labour Party (ALP), Coalition parties have long sought to discredit the ALP through reducing the credibility of unions. Indeed, the conflict between capital and labour is the core conflict within capitalism, so it should not surprise us that it is also central to political conflict in Australia, though usually it is not articulated this way.[4] It is, though, common to think of and depict people, interest groups or parties as being somewhere on a spectrum from ‘left’ (pro-labour) to ‘right’ (pro-capital). It is an idea that voters somehow manage to relate to in survey questions, and surveys over the past two decades using this measure have detected a gradual leftward shift, from the right towards the centre, in people’s self-assessment of their political positioning.[5]

How the system works

Patterns of policy need not reflect patterns of public opinion. The ideology of people in positions of power, the organisational ability of interest groups and the nature of the institutional framework all shape the direction of policy and may do so contrary to directions in public opinion.

There are three parties (groups) with a particular interest in the employment relationship:

- employees and their representatives (commonly unions)

- employers and their representatives (employer associations)

- the state.

Each affects rule-making associated with the employment relationship.

Unions

The shape of the union movement today reflects how unions have developed over the past 100 years. The trade union movement enables workers to act collectively, to influence policy decisions affecting workplaces, and enables workplace negotiations on pay and conditions of work.

The focus of trade unions is on the needs of members. However, their involvement in decision making is not limited to the workplace level – it can also be seen in their involvement in the community and in political lobbying. The Australian Council of Trade Unions (ACTU) has been the sole peak body for unions since the early 1980s, and it undertakes broad political and policy-based work as part of its activities. It has initiated various equal pay and other wage cases to the body now called the Fair Work Commission (FWC), and lobbied or negotiated with governments. Outcomes achieved over many years include ‘occupational health and safety laws, annual holidays legislation, superannuation, Medicare, the award system, penalty rates for overtime and weekend work, and workplace amenities’.[6]

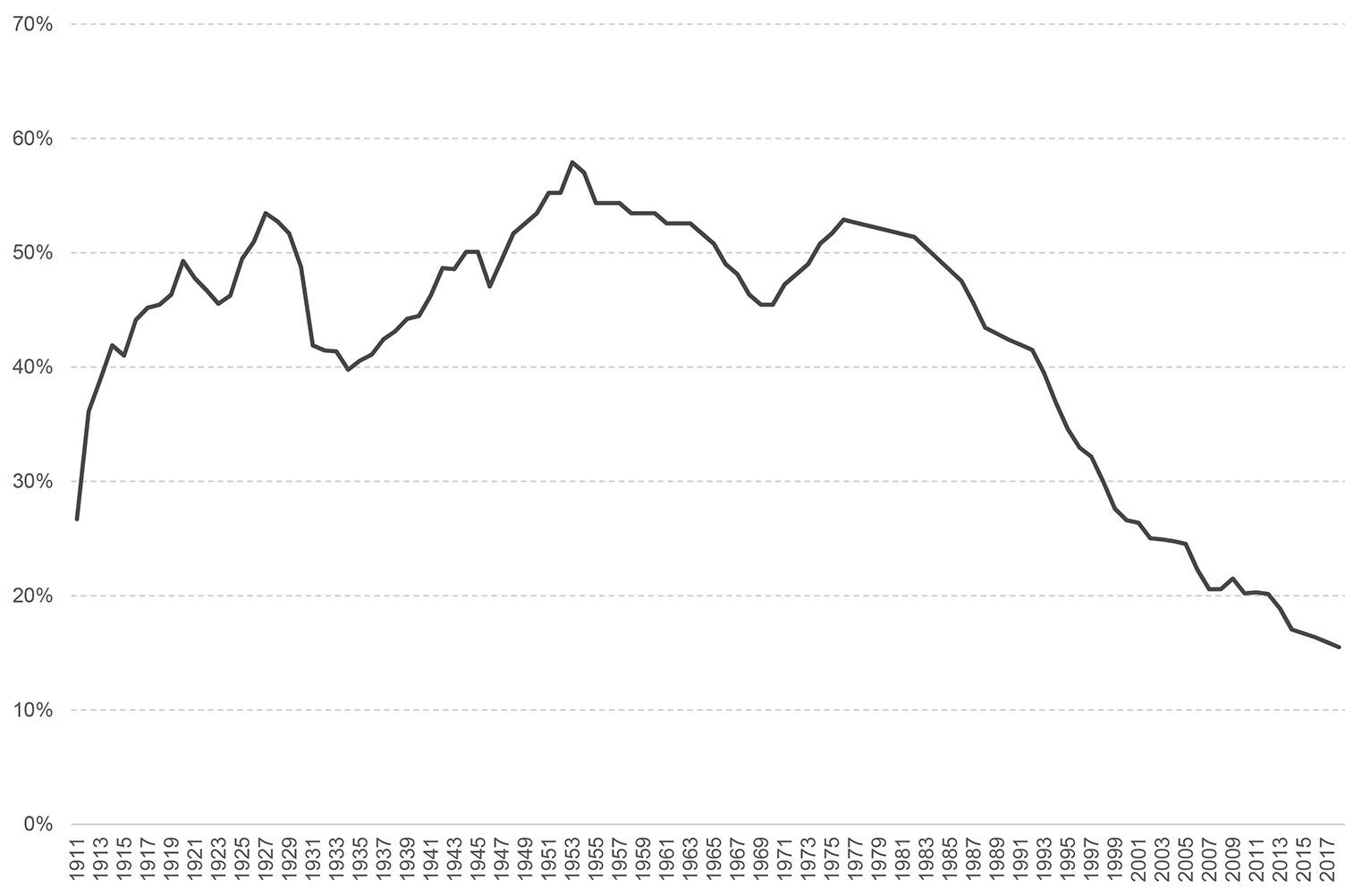

Under conciliation and arbitration, union density (the share of employees who are members of a union) went from 6 per cent in 1901 to around 60 per cent by the early 1950s.[7] From the 1980s, union density declined (see Figure 1), beginning with structural changes in the economy that favoured industries and occupations with low density but were not met with effective union responses, such as organising in new areas.[8]

In the 1990s, unions began a process of large-scale amalgamations to capitalise on economies of scale, but union density continued to decrease in the face of attacks by employers and various state and national governments. With the move to enterprise bargaining, the focus of industrial relations shifted to the workplace, but this was a level at which unions were often weakly organised, after focusing for many years on advocacy in tribunals and action in a small number of ‘hot spots’. By 2018 density was around 15 per cent and, with a delay, collective bargaining also declined.[9]

Employers and employer associations

Employers also form collective organisations. Employer associations are often regarded as the equivalent of unions for employers. Moreover, employers of most people are themselves corporations, which are collectives of capital. Thus, employer associations are industry-based collectives of collectives, formed to counter the associational power of unions.

The roles of employer associations vary, depending on the way they developed and the industry or region in which they traditionally operated. These roles have evolved through amalgamations, but have largely centred around the representation of political parties and developing responses to industry or national issues raised by unions. Their activities have changed as employment relations has become increasingly decentralised. They may provide services to their members to assist specifically with managing their employment relations issues.

The state

The term ‘state’ is used here to describe the various institutions used to regulate the employment relationship. These institutions include the legislature, executive and judiciary. The legislature consists of the parliament and is responsible for creating legislation. The judiciary interprets and applies legislation and can be responsible for ensuring that the executive and legislature act within the Constitution. The executive consists of the elected government as well as the various institutions that form part of the public bureaucracy.

The latter include the federal department responsible for employment relations (in 2019, Jobs and Small Business), the labour inspectorate (in 2019, called the Fair Work Ombudsman), Safe Work Australia, and the Australian Building and Construction Commission (ABCC). In addition, there are quasi-judicial bodies including the industrial tribunal (in 2019, called the Fair Work Commission), the Australian Human Rights Commission, and the Remuneration Tribunal.

The state’s role has substantially varied over time. For most of the 20th century, Australian industrial relations operated within the conciliation and arbitration system. That system originated in the 1890s, before the nation was federated, in response to bitter and costly disputes in several industries. Unions had strongly, but unsuccessfully, resisted cuts to wages and conditions. Employers had been unwilling to participate in voluntary conciliation or arbitration, and bloodshed had occurred when employers, workers and law enforcement clashed.

By 1904, federal legislation was introduced to formally regulate and provide a system for the negotiation of workers’ wages and conditions, and unions were recognised as registered entities. This centralised system of multilateral rule-making involved trade unions as representatives of workers, employer associations representing employers, and the industrial labour courts and tribunals. Federal and state governments did not directly determine labour standards at this time,[10] but they did regulate some internal affairs of unions and employer associations, as these were part of the system (some saw them as virtually an arm of the state[11]). Tribunal decisions around wages and conditions became binding, and the details were contained within instruments known as ‘awards’.

The central agency, originally the Conciliation and Arbitration Court, was split in the 1950s into a court and a tribunal. The latter, the Australian Conciliation and Arbitration Commission (ACAC), became the Australian Industrial Relations Commission (AIRC) and then Fair Work Australia (subsequently the FWC). In the long run, the decisions of the tribunals, although often contested, appeared to be similar to outcomes that the market would have delivered, apart from a tendency to produce a more egalitarian distribution of earnings, which also included progress towards equal pay for women.[12]

At the parliamentary level, there are deep divisions between the major political parties. In some ways these parties are the political manifestation of capital and labour. The unions created the ALP, and still have a formal role in it, though there are often wide political gulfs between them. The Liberal Party was established in the 1940s in an attempt to reorganise the then non-Labor parties (i.e. the parties of capital) to better fight the ALP, then in government. Its creation was facilitated by the newly established Institute of Public Affairs.

Elements determining pay and conditions

The legal ‘safety net’ for employees – the minimum conditions which should govern their work – has several components: a minimum wage, National Employment Standards (NES) set out in the Fair Work Act 2009 (Cth), and modern awards. On top of these sit, for a substantial minority of workers, enterprise agreements.

The minimum wage is set by the Fair Work Commission’s Expert Panel, taking effect from 1 July each year. The National Employment Standards are required by law to be provided to all employees. The NES and minimum wage applies to all employees as a ‘bottom floor’ set of minimum conditions. The NES includes provisions regarding:

- maximum weekly hours

- requests for flexible working arrangements

- parental leave and related entitlements

- annual leave

- personal/carer’s leave, compassionate leave, and family and domestic violence leave

- community service leave

- long-service leave

- public holidays

- notice of termination and redundancy pay

- provision of a fair work information statement to employees.[13]

Although seemingly detailed and prescriptive, there are loopholes in some of these provisions, so it is not as robust a list as it might initially appear. Employees who are employed under a modern award are entitled to minimum pay and other conditions outlined in the relevant award. Where an organisation has negotiated an enterprise agreement, pay and conditions for employees will be outlined in the enterprise agreement, which can be different to the award but should leave employees better off overall than if they were employed under the award. In addition, employees and employers may negotiate an individual flexibility arrangement (IFA) that can be used to implement more flexible work practices, particularly on hours of work. An IFA, in theory, cannot be used to erode the minimum rights of employees. Again, the employee should be better off overall when compared to the modern award or enterprise agreement that the IFA varies.

Modern awards protect a number of entitlements and these can include:

- minimum wages

- types of employment (e.g. full-time, part-time or casual)

- overtime and penalty rates

- work arrangements (e.g. rostering or variations to working hours)

- annual wage or salary arrangements

- allowances (e.g. for employees required to clean their uniform)

- annual leave loading and arrangements for taking leave

- superannuation

- procedures for consultation, representation and dispute settlement.[14]

Most modern awards are based on a designated industry or an occupation within a group of industries of employment. A miscellaneous award attempts to cover all remaining workers. Any who might not be covered, however, are still entitled to the minimum wage and the NES.[15]

The federal dimension

Federal industrial legislation in the 20th century relied on varied parts of the Constitution. Principally, the conciliation and arbitration power in section 51(xxxv) of the Constitution was used to encourage the settlement of disputes through bargaining at the enterprise level. Residual powers rest with the states, so at times 30 to 40 per cent of Australian employees were under state awards. While, in 1993, the external affairs power (section 51[xxix]) was used to provide for redress against unfair dismissal and unequal remuneration between men and women, this was historically unusual. That year, the corporations power (section 51[xx]) was used to allow the negotiation of enterprise flexibility agreements between incorporated employers and groups of employees without any representation by trade unions or employer associations. This use was widened in 2005 to form the basis for the entirety of the Howard government’s ‘WorkChoices’ legislation. The High Court validated this, and so responsibility for most industrial relations matters moved from the states to the federal government. To make this work, it was still necessary for the states to refer power on non-corporate employers to the federal government, which all states except Western Australia did. Most states retained the responsibility for their own employees (such as state employed teachers and nurses).

After that time, much of the WorkChoices legislation was wound back (especially regarding dismissal and individual contracts), and the Fair Work Act that replaced it has itself been amended several times, albeit in mostly minor ways. Regardless, the federal government has largely maintained responsibility for industrial relations.

Issues

We now turn to policy matters that have featured in political debates in recent Australian history. These include matters concerning wages policy, collectivism and individualism, union power and industrial conflict.

Wages policy, ‘the Accord’ and enterprise bargaining

Through the first half of the 20th century, awards became central to setting pay and conditions. They provided a framework for employers to adhere to for rewarding employees with wages and conditions of employment in return for their work effort. The award system was seen as offering stability to the economy and perhaps restraining strike activity. The number of awards grew as they covered an increasing range of industries. The number of award conditions contained within awards also grew. Furthermore, the government sought to protect local industries and jobs through tariffs and quotas.

However, by the late 1970s to early 1980s, economic circumstances were complex and changing. Most countries were experiencing simultaneous high inflation and unemployment, following oil price rises driven by the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries, and in Australia neither the Whitlam Labor government nor the conservative Fraser government had been able to effectively counter both, with their traditional demand-management policies.

In 1983, the ALP introduced the Prices and Incomes Accord, more commonly referred to as ‘the Accord’ that had been negotiated with the ACTU. It was a system of highly centralised wage determination and a means by which state intervention restructured the industrial relations system. The main logic was for labour to co-operate with the state to reduce both unemployment and inflation, through wage restraint (at or below inflation) supported by social expenditures such as the introduction of Medicare and tax cuts.[16] A secondary logic was for labour to co-operate with corporate management in finding ways of improving productivity at the workplace level. While productivity growth was quite high prior to the introduction of the Accord, it slowed substantially in the mid-1980s – firms had little incentive to engage in labour-saving technology once real wage costs were falling – and productivity and barriers to flexibility (discussed below) came to be seen as the major problem with the industrial relations system. The Accord was renegotiated several times – initially, in response to wage pressures arising from a large depreciation of the Australian dollar in 1985 – and subsequent versions (‘Marks’) of the Accord placed increasing emphasis on localised cost offsets or productivity gains. The Accord’s creation may have been the last time that national economic considerations fundamentally drove industrial relations policy.

By 1991, employers, unions and the Labor government had all decided, for varying reasons, to move away from centralised wage fixing, and this was reflected in Accord Mark V. In the April 1991 National Wage Case, the arguments of the parties for this move to ‘enterprise bargaining’ (EB) were rejected by the AIRC, but by October 1991 it reluctantly endorsed the move.[17] This was backed by 1992 legislation reducing the AIRC’s capacity to reject certified agreements and by wholesale legislative changes in 1993 (the Industrial Relations Reform Act 1993 [Cth]).[18] These formally established a right to strike in negotiation of a new enterprise bargaining agreement (EBA) – but nothing else – whereas previously, strikes had occurred in a legal grey zone with few restrictions. EBAs had to satisfy a ‘no disadvantage’ test, meaning workers on them should be no worse off than they would be under awards.

This emphasis on bargaining – where ‘the institutionalised arrangements by which employers and employees determine the terms and conditions of the employment relationship’[19] – starkly contrasted the heavy state involvement (via the AIRC) in earlier times. In the ideal form, trade unions would bargain for pay increases and improvements in workplace conditions where profits were achieved through employees’ efforts, and employers would bargain for further increases in productivity in return. Once agreement between all parties was reached, these EBAs would be made legally binding after approval by the AIRC. In practice, many saw this ideal as being constrained by employers focusing on cost reductions rather than productivity increases; the parties running out of ways to increase productivity through this mechanism; employers introducing productivity-enhancing measures outside the bargaining context; outcomes being determined by muscle, not merit; employers using the EB process to circumvent unions altogether; and subsequent changes to the EB law designed to favour the power of one side over the other.

With decreasing involvement in workplace matters, the role of the AIRC shifted to maintaining an appropriate safety net of minimum award wages and conditions. Changes in the safety net were meant to take account of inflationary pressures, the level of workforce participation and productivity growth, industrial action, broader social objectives and community expectations of fairness. Its first three safety net decisions in the early 1990s provided low increases ($8 per week) in award wages in line with the Accord partners’ interest in encouraging workers to move to enterprise bargaining. After 1996, when the Coalition government came to office and the Accord ended, the parties made divergent submissions to these safety net cases – eventually, the government stopped nominating a specific amount altogether – and the AIRC varied in the extent to which its decisions implicitly endorsed one side’s submissions over the other’s.

Eventually, the idea of setting the safety net at a level low enough to encourage workers to move to enterprise bargaining lost salience, not least because a large gap quickly opened up in most industries between award rates and EBA rates, but it was often the resistance of employers, rather than employees, that held back the growth of EB. New developments in economic research cast heavy doubt on the previous consensus amongst economists that minimum wage increases would raise unemployment.[20] Despite the claimed focus on the low paid, the inherently difficult circumstances of people who relied on award wages at or near the minimum wage led unions to lodge ‘Living Wage’ claims, seeking a large increase in minimum and award wages to deal with the problems facing the low paid, albeit with little success. While increases in award minimum rates may presently be above growth in the Consumer Price Index,[21] wage growth overall in 2018 were historically at very low rates in Australia and overseas.[22]

Pay equity

The concept of equity is concerned with fairness, derived from social justice principles of equal rights and access to, and full participation in, society. The difference between high and low wage earners is one aspect of pay equity. While a minimum wage aims to provide some standard of living to safeguard against poverty,[23] other inequities may persist due to other historical, systemic and social factors. For example, the 1907 Harvester court decision set the male basic wage to support his wife and five children.[24] This social norm of the time viewed the male as the worker and the female as the homemaker. This has been seen as reflecting a breadwinner/homemaker model, and perpetuating gender discrimination, manifesting in the issue of the gender pay gap.

Even after explicit pay discrimination based on gender was ended by the ACAC, traditionally male forms of work such as manual and heavy work have attracted a higher value than female forms of work, which embodied ‘softer’ skills, in occupations like nursing or child care. Whitehouse and Rooney[25] highlight the undervaluation of work performed by women, and Baird[26] reinforces this view, citing that our industrial relations system has had an ‘uncomfortably ambivalent relationship’ to women, casting women as either ‘ungendered’ workers (or equivalent to the male worker ideal type), or the ‘other’ type of worker (encumbered with care responsibilities outside of work). While this undervaluation affects specific jobs, other systemic biases also damage a woman’s position. For example, a policy focusing on promotion linked to length of service may inadvertently discriminate against women, due to the taking of maternity leave.

Despite a range of state interventions toward providing pay equity, including a major Convention,[27] anti-discrimination and equal opportunity legislation, and various equal pay decisions by tribunals, the gender pay gap remains at around at 14 per cent of male hourly earnings.[28] Pay inequality also extends to a range of vulnerable groups in the labour market who are denied access to good quality and well-paid work experience and less bargaining power, including Indigenous Australians,[29] people living with disabilities,[30] youth, and temporary and skilled migrant workers.[31] ‘Neoliberal’ policies outside employment relations appear to worsen this disadvantage, and increase poverty (especially when we compare different countries), with little or no consistent gain in terms of productivity.[32]

Individualism and collectivism

One of the key left–right differences in industrial relations policy is the emphasis on collectivism versus individualism. For example, statutorily providing for individual contracts, known as Australian Workplace Agreements (AWAs), was a focus of amendments to federal legislation of the Howard Coalition government, through the Workplace Relations Act 1996 (Cth). Lack of control in the Senate saw a watering down of the Coalition’s original intentions.[33] However, this changed in 2005 when the Coalition gained control of the Senate and enacted the Workplace Relations Amendment (WorkChoices) Act 2005 (Cth), more commonly known as the ‘WorkChoices’ legislation.

The powers of the AIRC were further limited. WorkChoices gave AWAs supremacy over EB agreements or awards, and moved the role of fixing minimum wages and casual loadings to the Australian Fair Pay Commission (AFPC). Only five minimum working conditions needed to be included in awards and AWAs. The ‘no disadvantage’ test was abolished.[34] AWAs frequently reduced penalty rates (wage premiums for anti-social working hours), overtime and shift allowances. Small and medium businesses (with less than 101 employees) became exempt from unfair dismissal laws, giving employers ‘greater freedom over the terms of which they can hire and fire workers’.[35] There were publicised examples of people given a choice between a pay cut and losing their job.[36]

The issue was central to the 2007 federal election. The unions’ ‘Your Rights @ Work’ (YRAW) campaign substantially helped the ALP return to power at the 2007 election.[37] The ALP subsequently reinstated unfair dismissal protections and phased out AWAs. Its Fair Work Act 2009 re-established the integrity of awards, with some changes, in particular a reduction in their number and overlap and an increase in their ability to be varied at the workplace level by ‘agreement’ – hence the new term ‘modern awards’.[38] It replaced the AIRC with Fair Work Australia (FWA) – it was, after all, the ‘Fair Work Act’ – and replaced or renamed several other Coalition-established institutions. However, not all aspects of WorkChoices were changed. Unions did not achieve full reinstatement of workplace entry rights.[39] In addition, industrial action by trade unions remained unlawful in many contexts, and requirements for a secret ballot were modified but largely retained. Good faith bargaining requirements were introduced for negotiating EB agreements (section 228 of the Fair Work Act 2009). The Fair Work Act 2009 reintroduced a stronger version of the ‘no disadvantage’ test called the ‘better off overall’ test, or ‘BOOT’,[40] designed to ensure that a worker is better off overall under an agreement when compared to the equivalent industry award. The ten minimum NES conditions, discussed earlier in this chapter, must be satisfied. The ALP also initiated a process leading to the introduction of universal paid parental leave.

Flexibility and insecurity

The basic architecture of the Fair Work Act 2009 had, by 2019, changed little since its introduction, despite six years of Coalition government from 2013. The Coalition found it difficult to get radical changes through the Senate, and a broader agenda had been stymied since 2008, by the 2007 election result.

Nonetheless, pressures for change continued, because of the ongoing employer urge for flexibility since the Accord days. It was usually controversial because increased flexibility for employers would be mirrored in increased insecurity for employees. Over the period from 2013, matters affecting pay and conditions became controversial, because of actions of institutions promoting flexibility. The FWC in 2017 decided to reduce Sunday penalty rates in retail and hospitality, following employer submissions focusing on the need for greater flexibility in those industries and the employment opportunities it would allegedly create, a report by the Productivity Commission that made similar recommendations and statements from individual Coalition politicians favouring such a cut.[41]

The issue was particularly salient because of its impact on low-income workers and, implicitly, the potential for eventual flow-on to other workers. Soon, ‘insecurity’ became a major issue, with unions focusing on high rates of casualisation, labour hire, franchise employment, the use of ‘independent’ contractors, and continuing growth in underemployment, with academic attention focusing on several of these issues.[42] The emergence of changing business models and the growth of the ‘platform’ or ‘gig’ economy heightened focus on these issues.[43] As such, individual jurisdictions have introduced legislation aimed at specific issues such as labour hire or occupational health and safety.[44]

Another controversial institution was the Fair Work Ombudsman (FWO), charged with ensuring compliance with the system. Employers in a range of industries, but especially horticulture and hospitality, were found (often through media exposés) to be exploiting and underpaying workers (what the ACTU called ‘wage theft’), and the FWO was frequently criticised for inaction on these issues – in effect, for allowing employers too much flexibility in the determination of pay and conditions. In the context of extensive media coverage before the 2016 election, the Coalition foreshadowed, and eventually introduced, legislation making accessorial, franchisor and holding company employers liable for certain contraventions of workplace laws within related organisations.[45] The issue continued to have salience, especially for the most vulnerable workers (migrants on temporary visas), and in the lead-up to the 2019 election the Coalition government received a report from the migrant workers taskforce and promised to implement most of its recommendations.

Unions and industrial conflict

Despite lower density, unions attract a lot of political attention. This is because they still wield considerable political mobilising ability (few other union movements would be able to claim the impact Australian unions’ 2007 YRAW campaign had on an election result), they are the largest organised part of civil society, and they are formally linked to the Coalition’s political enemy, the ALP. Their influence on Labor in government is much less now, however, with the relationship having shifted from one of being an ‘equal player’ during the Accord years, to that of an ‘interest group’ in political negotiations over the Fair Work Act.

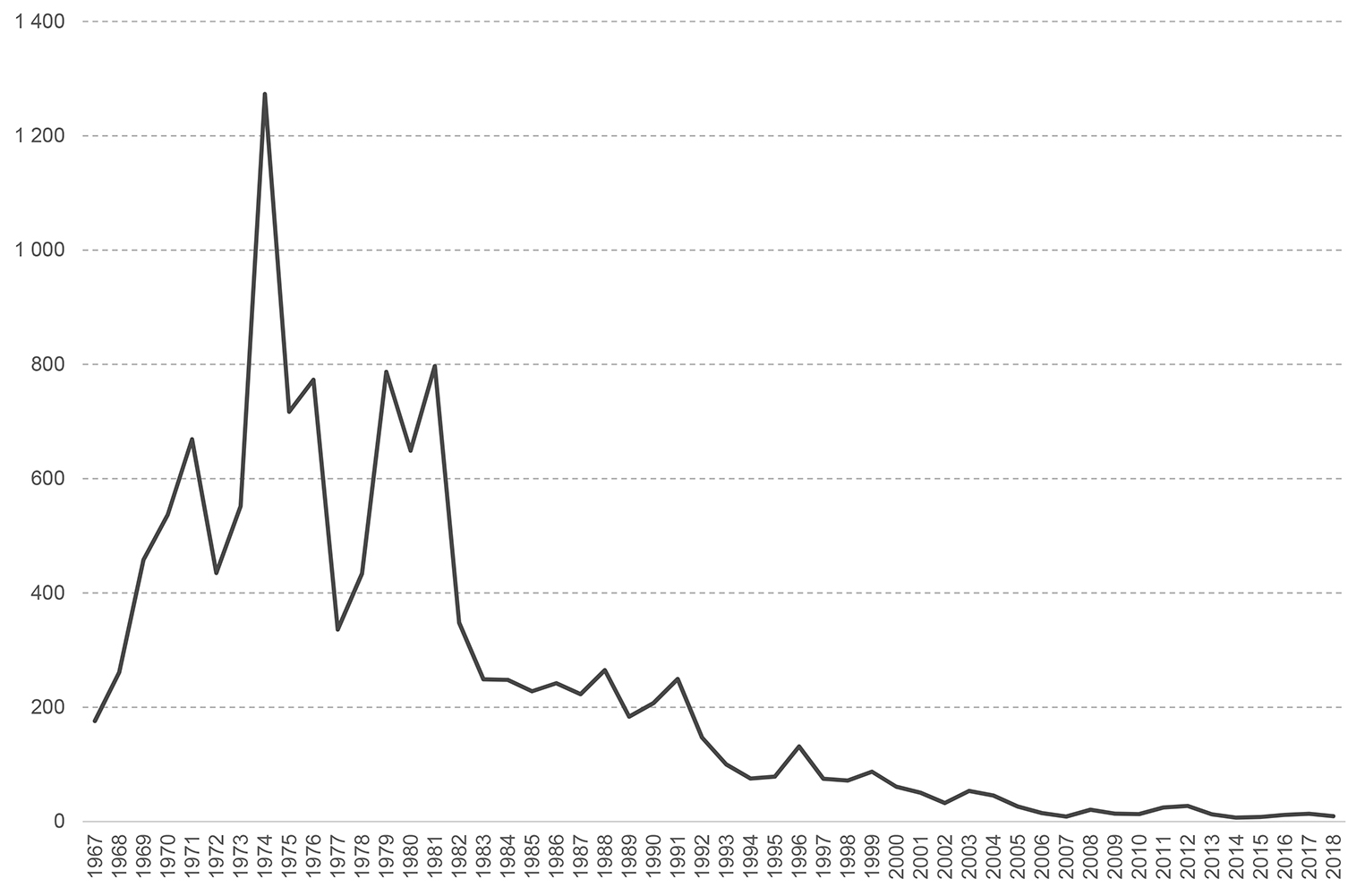

After losing status during the WorkChoices years, unions are again recognised as bargaining representatives within collective bargaining processes, under the Fair Work Act 2009,[46] but both union internal affairs and the undertaking of industrial conflict are regulated in extensive detail, especially by comparison with almost all other industrialised nations. Several of the procedures in place create intentional difficulties for unions (having been introduced under WorkChoices but subject only to minor changes by the Fair Work Act). Their relevance has sometimes only been made apparent through some important decisions by courts or the FWC. For example, one appears to make it easy for employers to terminate an agreement after its formal term expires (weakening the bargaining power of workers, whose pay and conditions can technically be reduced from the EB levels to award levels). Another makes it easy for employers to obtain termination of otherwise legal industrial action if it is inconveniencing third parties. There is a serious question in Australia as to whether a genuine right to strike exists.[47] These features, and other aspects of the system that tipped the balance of power away from unions, led to unions running the ‘Change the Rules’ political campaign in the lead-up to the 2019 election. In contrast to the union movement’s success in swinging votes in the 2007 and 2016 elections,[48] this campaign had limited impact. The level of industrial conflict has been much lower in recent years than in the 20th century (see Figure 2).

An example of the high level of attention to union regulation in Australia is found in the building industry. The Australian Building and Construction Commission (ABCC) was created by the Coalition government in 2005 with wide powers to monitor, investigate and enforce alleged breaches of industrial law. The ABCC was a government agency, not an independent tribunal, with extensive powers to prosecute unions or their officials or members, and to compel the answering of questions, with much higher fines available than for other industries (including, in some instances, jail). It restricted union access to worksites when concerns about employee working conditions arose unless stringent documentary requirements were met. The ABCC was abolished under the Labor government in 2012 and replaced by the less powerful Fair Work Building and Construction (FWBC) agency, but reinstated, after several years of Senate resistance, by the Coalition in 2016, although the latter had already appointed strong sympathisers to the FWBC anyway.

The government as employer

A quite different aspect of industrial relations public policy is the government’s role as employer. Sometimes it has led the way in advancing labour interests – for example, the Whitlam Labor government took a ‘pace setter’ role in increasing annual leave and introducing maternity leave. As public sector work is highly regulated, the gender pay gap is lower in the public sector than in the private sector.[49] On the other hand, public sector employers also experience the budgetary cost of wage increases, and so governments at the federal and state level, both Coalition and ALP, may impose caps on negotiated wage increases or even attempt to reduce conditions, leading at times to major industrial action.[50]

Conclusions

Most public policy in industrial relations, particularly since the 1990s, has been driven by two things: political ideology and each political party’s perception of what the political environment will permit. For the ALP, there is an urge to improve the position of labour (and no love of ‘the big end of town’), but it is constrained by what it considers the business sector and the media will accept. For the Coalition, there is an urge to improve the position of capital (and no love of unions), but it is constrained by what it considers the electorate will allow. Occasionally, especially if an election is near, a party will enact policies that are counter to its traditional base, because of political considerations. Both sides are also constrained, in terms of legislation, by what the Senate will allow, but they (particularly the Coalition) have found that making the ‘right’ appointments of personnel to key positions can be at least as important as the formal aims of an organisation or its governing legislation.

Industrial relations policies are rarely evaluated in the way of public policies in several other areas, and if they are it is often for specific purposes, reflected in the bodies or individuals chosen for the task. A feature of industrial relations policy is the use of inquiries to justify political positioning, and to provide some distancing for a government that wants to test public reaction to ideas. Two recent examples are the Heydon Royal Commission into Trade Union Governance and Corruption, and a Productivity Commission inquiry into workplace regulations.[51] Another feature is the use of the rationale of ‘productivity’ to justify changes, even when the evidence on this is limited or contradictory – the most glaring example being reform in the building and construction industry.[52] That is, even where the reason is ideology or politics, the stated rationale may be about productivity, flexibility or economic growth.

Although all areas of public policy are influenced by ideology and politics, this phenomenon is particularly marked in industrial relations policy. While ‘evidence-based policy’ may be a phrase that haunts many other areas of public policy, its ghost is barely evident here.

References

Alexander, Robyn, John Lewer and Peter Gahan (2008). Understanding Australian industrial relations. South Melbourne: Thomson.

Allan, C., A. Dungan and D. Peetz (2010). ‘Anomalies’, damned ‘anomalies’ and statistics: construction industry productivity in Australia. Journal of Industrial Relations 52(1): 61–79. DOI: 10.1177/0022185609353985

Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) (various years). Employee earnings, benefits and trade union membership, Australia. Cat. No. 6310.0. Canberra: ABS.

—— (various years). Industrial disputes, Australia. Cat. No. 6321.0. Canberra: ABS.

—— (various years). Trade union statistics, Australia. Cat. No. 6323.0. Canberra: ABS.

—— (various years). Trade union members. Cat. No. 6325.0. Canberra: ABS.

—— (various years). Characteristics of employment. Cat. No. 6333.0. Canberra: ABS.

Baird, Marian (2016). Policy tensions: women, work and paid parental leave. In Keith Hancock and Russell Landsbury, eds. Industrial relations reform: looking to the future, 85–104. Annandale, NSW: Federation Press.

Balnave, Nikola, Janine Brown, Glenda Maconachie and Raymond Stone (2009). Employment relations in Australia, 2nd edn. Milton, Qld: John Wiley & Sons.

Barry, Michael, and Kevin You (2018). Employer association matters in Australia in 2017. The Journal of Industrial Relations 59(3): 288–304. DOI: 10.1177/0022185617693873

Birch, Elisa, and David Marshall (2018). Revisiting the earned income gap for Indigenous Australian workers: evidence from a selection bias corrected model. Journal of Industrial Relations 60(1): 3–29. DOI: 10.1177/0022185617732365

Bray, Mark (2011). The distinctiveness of modern awards. In Marian Baird, Keith Hancock and Joe Issac, eds. Work and employment relations: an era of change. Essays in honour of Russell Lansbury, 17–33: Annandale NSW: Federation Press.

Brown, William (2011). How do we make minimum wages effective? In Marian Baird, Keith Hancock and Joe Issac, eds. Work and employment relations: an era of change. Essays in honour of Russell Lansbury, 167–77. Annandale, NSW: Federation Press.

Bukarica, Alex, and Andrew Dallas (2012). Good faith bargaining under the Fair Work Act 2009. Annandale, NSW: Federation Press.

Campbell, Iain, and John Burgess (2018). Patchy progress? Two decades of research on precariousness and precarious work in Australia. Labour and Industry: A Journal of the Social and Economic Relations of Work 28(1): 48–67. DOI: 10.1080/10301763. 2018.1427424

Card, D., and A. Krueger (1995). Myth and measurement. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Cooper, Rae (2016). Consensus in industrial relations policy and politics in Australia 2007–2015. In Keith Hancock and Russell Lansbury, eds. Industrial relations reform: looking to the future, 66–84. Annandale, NSW: Federation Press.

Cooper, Rae, and Bradon Ellem (2011). Trade unions and collective bargaining. In Marian Baird, Keith Hancock and Joe Issac, eds. Work and employment relations: an era of change. Essays in honour of Russell Lansbury, 34–48. Annandale, NSW: Federation Press.

Dabscheck, Braham (1989). Australian industrial relations in the 1980s. Melbourne: Oxford University Press.

Fair Work Commission (2017). Annual wage review. Canberra: Fair Work Commission.

Fair Work Ombudsman (n.d.). Accessorial liability – the involvement of others in a breach. Canberra: Australian Government. https://bit.ly/2BFo70d

——— (2018a). Fair work handbook. Canberra: Australian Government.

——— (2018b). Compliance and enforcement policy. Canberra: Australian Government.

Forsyth, Anthony (2017). Industrial legislation in Australia in 2016. Journal of Industrial Relations 59(3): 323–39. DOI: 10.1177/0022185617693876

Gahan, Peter, Andreas Pekarek and Daniel Nicholson (2018). Unions and collective bargaining in Australia in 2017. Journal of Industrial Relations 60(3): 337–57. DOI: 10.1177/0022185618759135

Hancock, Keith (2016). Reforming industrial relations: revisiting the 1980s and the 1990s. In Keith Hancock and Russell Lansbury, eds. Industrial relations reform: looking to the future, 16–39. Annandale, NSW: Federation Press.

Healy, Joshua, Daniel Nicholson and Andreas Pekarek (2017). Should we take the gig economy seriously? Labour and Industry: A Journal of the Social and Economic Relations of Work 27(3): 232–48. DOI: 10.1080/10301763. 2017.1377048

Howard, William (1977). Australian trade unions in the context of union theory. Journal of Industrial Relations 19(3): 255–73. DOI: 10.1177/002218567701900303

Kaine, Sarah, and Martin Boersma (2018). Women, work and industrial relations in Australia in 2017. Journal of Industrial Relations 60 (3): 317–36. DOI: 10.1177/0022185618764204

Lansbury, Russell (2018). The changing world of work and employment relations: a multi-level institutional perspective of the future. Labour and Industry: A Journal of the Social and Economic Relations of Work 28(1): 5–20. DOI: 10.1080/10301763. 2018.1427425

McAllister, Ian, and Sarah Cameron (2014). Trends in Australian public opinion: results from the Australian Election Survey 1987–2013. Canberra: Australian National University College of Arts and Social Sciences.

McCallum, Ron (2011). Legislated standards: the Australian approach. In Marian Baird, Keith Hancock and Joe Issac, eds. Work and employment relations: an era of change. Essays in honour of Russell Lansbury, 6–16. Annandale, NSW: Federation Press.

McCrystal, Shae (2019). Why is it so hard to take lawful strike action in Australia? Journal of Industrial Relations 61(1): 129–44. DOI: 10.1177/0022185618806949

Muir, Kathie, and David Peetz (2010). Not dead yet: the Australian Union movement and the defeat of a government. Social Movement Studies 9(2): 215–28. DOI: 10.1080/14742831003603380

Oliver, Damian, and Serena Yu (2018). The Australian labour market in 2017. Journal of Industrial Relations 60(3): 298–316. DOI: 10.1177/0022185618763975

Peetz, David (2019). The realities and futures of work. Canberra: ANU Press. DOI: 10.22459/RFW.2019

—— (2018). The industrial relations policy and penalty. In Anika Gauja, Peter Chen, Jennifer Curtin and Juliet Pietsch, eds. Double disillusion: the 2016 Australian federal election, 519–48. Canberra: ANU Press.

—— (2016a). Industrial action, the right to strike, ballots and the Fair Work Act. Australian Journal of Labour Law 29: 133–53.

—— (2016b). The Productivity Commission and industrial relations reform. The Economic and Labour Relations Review 27(2): 164–80. DOI: 10.1177/1035304616649305

—— (2012). The impacts and non-impacts on unions of enterprise bargaining. Labour and Industry: A Journal of the Social and Economic Relations of Work 22(3): 237–54. DOI: 10.1080/10301763.2012.10669438

—— (2007). Collateral damage: women and the workchoices battlefields. Hecate 33(1): 61–80.

Peetz, David, and Janis Bailey (2012). Dancing alone: the Australian union movement over three decades. Journal of Industrial Relations 54(4): 525–41. DOI: 10.1177/0022185612449133

Peetz, David, and Georgina Murray (2017). Women, labour segmentation and regulation: varieties of gender gaps. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Pekarek, Andreas, Ingrid Landau, Peter Gahan, Anthony Forsyth and John Howe (2017). Old game, new rules? The dynamics of enterprise bargaining under the Fair Work Act. Journal of Industrial Relations 59(1): 44–64. DOI: 10.1177/0022185616662311

Rawling, Michael, and Eugene Schofield-Georgeson (2018). Industrial legislation in Australia. Journal of Industrial Relations 60(3): 378–96. DOI: 10.1177/0022185618760088

Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) (1997). Australian economic statistics 1949–1950 to 1996–1997. Occasional Paper No. 8. Sydney: RBA. https://www.rba.gov.au/statistics/frequency/occ-paper-8.html

Ressia, Susan, Glenda Strachan and Janis Bailey (2017). Going up or going down? Occupational mobility of skilled migrants in Australia. Asia Pacific Journal of Human Resources 55: 64–85. DOI: 10.1111/1744-7941.12121

Stewart, Andrew (2016). WorkChoices, fair work and the role of the ‘independent umpire’. In Keith Hancock and Russell Lansbury, eds. Industrial relations reform: looking to the future, 40–65. Annandale, NSW: Federation Press.

Stewart, Andrew, Jim Stanford and Tess Hardy (2018). The wages crisis in Australia: what it is and what to do about it. Adelaide: University of Adelaide Press.

Stewart, Andrew, and George Williams (2007). WorkChoices: what the High Court said. Annandale, NSW: Federation Press.

United Nations (1951). Equal Remuneration Convention (No. 100). https://www.un.org/ruleoflaw/blog/document/equal-remuneration-convention-1951-no-100-2/

Werth, Shalene (2015). Managerial attitudes: influences on workforce outcomes for working women with chronic illness. Economic and Labour Relations Review 26(2): 296–313. DOI: 10.1177/1035304615571244

Whitehouse, Gillian, and Tricia Rooney (2011). Approaches to gender-based underevaluation in Australian industrial tribunals: lessons from recent childcare cases. In Marian Baird, Keith Hancock, and Joe Issac, eds. Work and employment relations: an era of change. Essays in honour of Russell Landsbury, 109–123. Annandale, NSW: Federation Press.

Willis, Ralph, and Kenneth Wilson (2000). A brief history of the Accord. In Kenneth Wilson, Joanne Bradford and Maree Fitzpatrick, eds. Australia in Accord: an evaluation of the Prices and Incomes Accord in the Hawke–Keating years, 1–18. Footscray, Vic.: South Pacific Publishing.

Workplace Gender Equality Agency (2019). The gender pay gap. https://www.wgea.gov.au/topics/the-gender-pay-gap

About the authors

Susan Ressia is a lecturer in the Department of Employment Relations and Human Resources at Griffith University, Brisbane, Australia. Her research focuses on the job search experiences of independent non-English speaking background skilled migrants in Australia. Susan’s research interests also include the areas of work–life balance, managing diversity, intersectionality, equality and social justice issues. Susan is co-author of Employment relations: an integrated approach (2nd edn. 2018) and Work in the 21st century: how do I log on? (2017). She has also published in Gender, Work and Organization and the Asia-Pacific Journal of Human Resources.

Shalene Werth is a senior lecturer in the School of Management and Enterprise at the University of Southern Queensland. Her research interests include the regulation of work, workplace diversity and inclusion, and specifically attitudes to disability and chronic illness in the workplace. Shalene co-edited the book: Work and identity: contemporary perspectives on workplace diversity (2019), as well as the ‘Researching Diversity’ section of Labour and Industry (Vol 29, No. 1).

David Peetz is professor of employment relations at Griffith University. He previously worked at the Australian National University and in the then Commonwealth Department of Industrial Relations, spending over five years in its Senior Executive Service. He has undertaken work for unions, employers and governments of both political persuasions. He is the author of Unions in a contrary world (1998) and Brave new workplace (2006) and co-author of Women of the coal rushes (2010), in addition to numerous academic articles, papers and reports, as well as articles for The Conversation. He is a Fellow of the Academy of the Social Sciences.

- Ressia, Susan, Shalene Werth and David Peetz (2024). Work, employment and industrial relations policy. In Nicholas Barry, Alan Fenna, Zareh Ghazarian, Yvonne Haigh and Diana Perche, eds. Australian politics and policy: 2024. Sydney: Sydney University Press. DOI: 10.30722/sup.9781743329542. ↵

- Alexander, Lewer and Gahan 2008, 22. ↵

- Peetz 2019. ↵

- Peetz 2018. ↵

- McAllister and Cameron 2014. ↵

- Balnave et al. 2009, 126. ↵

- Gahan, Pekarek and Nicholson 2018; Peetz and Bailey 2012. ↵

- Peetz and Bailey 2012, 529. ↵

- Gahan, Pekarek and Nicholson 2018. ↵

- McCallum 2011. ↵

- For example, Howard 1977. ↵

- Peetz 2016a. ↵

- Fair Work Ombudsman 2018a. ↵

- Fair Work Ombudsman 2018b, 4–5. ↵

- Fair Work Ombudsman 2018b, 4–5. ↵

- Dabscheck 1989; Hancock 2016; Willis and Wilson 2000. ↵

- Willis and Wilson 2000. ↵

- Pekarek et al. 2017. ↵

- Bray 2011, 19. ↵

- Card and Krueger 1995; Fair Work Commission 2017. ↵

- Oliver and Yu 2018. ↵

- Gahan, Pekarek and Nicholson 2018; Stewart, Stanford and Hardy 2018. ↵

- Ex parte H.V. McKay (1907) 2 CAR 1 (Harvester). ↵

- Brown 2011. ↵

- Whitehouse and Rooney 2011. ↵

- Baird 2016, 85. ↵

- United Nations 1951. ↵

- Workplace Gender Equality Agency 2019. ↵

- Birch and Marshall 2018. ↵

- Werth 2015. ↵

- Campbell and Burgess 2018; Ressia, Strachan and Bailey 2017. ↵

- Peetz 2012. ↵

- McCallum 2011; Stewart 2016. ↵

- McCallum 2011; Stewart 2016. ↵

- Stewart and Williams 2007, 33. ↵

- Peetz 2007. ↵

- Cooper 2016; Muir and Peetz 2010. ↵

- Bukarica and Dallas 2012; Stewart 2016. ↵

- Muir and Peetz 2010. ↵

- Bukarica and Dallas 2012; Cooper and Ellem 2011. ↵

- Kaine and Boersma 2018; Oliver and Yu 2018; Peetz 2016b. ↵

- Campbell and Burgess 2018, 51; Healy, Nicholson and Pekarek 2017. ↵

- Healy, Nicholson and Pekarek 2017; Lansbury 2018. ↵

- Rawling and Schofield-Georgeson 2018. ↵

- Barry and You 2018; Fair Work Ombudsman, n.d.; Rawling and Schofield-Georgeson 2018. ↵

- Bukarica and Dallas 2012. ↵

- McCrystal 2019. ↵

- Peetz 2018. ↵

- Kaine and Boersma 2018; Peetz and Murray 2017. ↵

- Gahan, Pekarek and Nicholson 2018. ↵

- Forsyth 2017; Peetz 2016a. ↵

- Allan, Dungan and Peetz 2010. ↵