8 The public sector

Isi Unikowski and John Wanna

Key terms/names

departments and statutory agencies, digital era governance, federalism, new public governance, new public management, Northcote-Trevelyan, not-for-profit sector, private sector, public sector, public value governance, Westminster system or tradition, Woodrow Wilson

Without reading on, try to guess when the following was written:

There is scarcely a single duty of government which was once simple which is not now complex; government once had but a few masters; it now has scores of masters … at the same time that the functions of government are every day becoming more complex and difficult, they are also vastly multiplying in number.[1]

Does it sound familiar? In fact, these comments were made in a classic of public administration literature in 1887 by Woodrow Wilson, who would become the USA’s 28th president. Leaving aside the archaic expression, these comments could have been made today. It is remarkable how frequently speeches by ministers and public servants, and academic books and articles, mention the increasing complexity of the public sector and the demands upon it.[2]

The contemporary relevance of Wilson’s comments suggests that nothing about ‘the public sector’ is ever settled for very long. There are no issues regarding its scope, size, reasons for being, ways of working, norms, values and practices that cannot be and have not been contested and debated since the emergence of the modern state.

Accordingly, rather than summarising a number of static terms and technical definitions that can be found in any standard textbook on the subject, which we would then have to qualify with caveats, this chapter considers the most important questions about the public sector and why these keep coming up. It then shows how the answers to these questions have changed over time, and how they will continue to do so.

What is the public sector?

The question of what differentiates the public sector from the private and community, or not-for-profit, sectors lies at the heart of perennial debate around the world about what governments should be doing and, consequently, how big their public sectors should be.

The easiest way to start is simply to define the public sector as the outcome of a set of choices citizens and governments make about two questions:

- What do citizens and communities want and need in terms of public provision?

- How should governments respond to these expectations?

The public sector’s role and shape can be seen as a collective approach to the things governments want to provide or impose, including the allocation of resources, production of goods, delivery of services and regulation of activity in society.

More specifically, we can view these functions of government in terms of the economic, political and/or legal purposes they fulfil:

- Economic purposes are achieved by governments performing a rebalancing function in society by reallocating resources through taxes and charges (e.g. redistributing from the rich to the poor or aged through social welfare and the age pension).

- Governments are often required to provide goods and services that the market has failed to produce or cannot easily produce. Street lights, public roads, utilities, telecommunication, navigation across air and sea and, historically, broadcasting and postal services are all delivered by public provision because private markets will not generally supply goods or services that benefit people regardless of whether they have paid for them.

- Governments sometimes produce monopolistic goods and services (e.g. water, electricity and sewerage) because the private sector may not provide them at a price or at a level of efficiency that is in the public interest. Another reason for this provision is the long-term investment required and the extensiveness of the costs associated with supply.

- Governments are compelled to act as a community protector or insurer of last resort (that is, providing protection against risks that are too great for the private sector to handle); for example, dealing with terrorism and national security, conducting wars, dealing with natural disasters and epidemics and combatting major crises affecting society, such as financial or economic crises.

- Turning to the public sector’s political purposes, governments respond to electoral pressures and voter preferences (for more benefits, say, or for extended services). Political parties channel voter preferences and campaign for office on policy platforms, with winning parties expected to deliver on their agendas.

- The public sector fulfils important legal functions and provides administrative services to ensure the rules and stability a functioning society needs are in place. These include frameworks for the operation and enjoyment of liberty and property, particularly law enforcement, courts and tribunals and bodies protecting human rights. They also include regulatory bodies governing matters such as safety, commerce and consumer protection.

In summary, comments on the role of the public sector that were made two decades ago by the US organisational theorist Herbert Simon are still relevant today: ‘At a point in history where cynicism about democracy and distrust of government are rampant, we need to remind ourselves daily that government performs a myriad of tasks that are vital to the health and future of our society.’[3]

Nevertheless, government decisions about what goods and services to supply, how to do so and how much of particular goods should be supplied are always contestable, even in the case of core public goods like defence, the courts, the police, public health, education and so on. These are matters that the political system determines, just as private markets determine how much of a private good is produced and sold. Below we will explore some of the ways such issues have been dealt with in the past.

Public sector governance

The questions of how much control governments can and should exert over the public sector, to what ends and in what ways have shaped much of the public sector’s history. The discussions in the following sections of the appropriate size of the public sector and how its structures and functions have changed over time reflect the different views and values on which these questions about roles, purposes and resources turn.

Two important sets of principles provide the norms and conventions that guide and shape the structures and functions of the public sector. The first may be broadly referred to as the Westminster tradition of public service. This tradition can be traced back to the 1854 Northcote-Trevelyan Report to the British government. This report essentially established the Westminster tradition of a professional and non-partisan public service recruited on merit rather than patronage. The Westminster tradition had a formative effect on the development of the Australian colonial governments at the time, and, subsequently, on the Commonwealth government.[4]

The tradition includes the principle that the public service is accountable to ministers, and ministers are individually and collectively accountable to parliament and the electorate. The Westminster tradition clearly distinguishes between the political role of ministers, who ‘have the last word’ on all matters for which they are responsible, and a bureaucracy that is non-partisan, in that it can only be appointed and removed according to legislated rules, works loyally for whoever occupies the ministry, regardless of their political stance, and strenuously avoids active political participation.[5] The principle of ministerial control over the departments and agencies in their areas of responsibility is a pre-eminent factor in determining how the public sector is structured, a matter we return to in the next section.

Australia’s federal system provides the second set of norms and principles governing the public sector. The public sector operates at three levels of government: the national government, state and territory governments and municipal governments. Officials work with one another within each of these levels, and across the Commonwealth–state and state–local levels to develop and implement government policies and programs, particularly when national policy frameworks are needed to deliver economic, environmental or other reforms. The federal system shapes the way policies are designed and implemented by the three levels of government, including how, when and to what extent the different levels of government engage with one another, how responsibilities for policy design and delivery are allocated, how performance is measured and reported and, perhaps most importantly, how the resources for these functions are collected and distributed.

The structure of the public sector

The relative independence of a public sector organisation from the government of the day is a fundamental design principle inherited from the Westminster tradition.[6] Within that context, the structures, forms and functions of the public sector at any time reflect government choices about what public goods and services to supply, to what extent and in what manner. Accordingly, the way public sector bodies are set up and function varies considerably along a continuum from the big, traditional departments that implement government policies in areas like immigration, transport, the environment and so on, through to ‘corporations’ controlled by governments but largely managed on a commercial basis.

The core public sector consists of departments and agencies that are under direct ministerial control. They are mainly financed by taxation, which they redistribute through subsidies, grants and welfare payments. They may also provide a range of services directly and free of charge (e.g. defence, education, health) or at prices well below what the commercial market would charge (e.g. subsidised housing).[7]

Governments may also set up semi-autonomous statutory agencies and corporations for reasons of efficiency, to drive innovative delivery or because the agency needs to be able to make decisions free of ministerial intervention (such as the Australian Taxation Office, the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission or state government environment protection agencies). In practice, statutory agencies are still subject to political and financial control by the government of the day because they depend on the government for their resources, their governing legislation can always be repealed or amended and individuals who fill statutory offices are usually appointed by the government.[8]

Public corporations are agencies that operate independently of government and may have their own sources of revenue in addition to direct public funding. They may compete in private markets and make profits. Public corporations include the Reserve Bank, Australia Post, the National Broadband Network, state government housing schemes and state-owned bodies that operate power and water supplies.[9]

Any neat delineation between the public and private sectors is challenged by increasing collaboration between governments, the private sector and the not-for-profit sector[10] in designing and delivering goods and services. Australian governments have a long history of relying on the not-for-profit sector, and in some cases the private sector, to assist with the provision of services and to contribute to their design. Governments partner with the not-for-profit sector for the delivery of a range of community, employment, education, health and other services through contracted networks.

Since 2000, governments have shifted towards this mode of delivering services. As a result, total government funding for the not-for-profit sector has increased significantly since 2000. Almost half (46 per cent) of Commonwealth and state/territory government agencies surveyed in 2010 reported that not-for-profit organisations made up three-quarters or more of the external organisations providing services on their behalf.[11]

In the private sector’s case, governments transfer risks to companies in return for financial rewards and incentives, through public–private partnerships for the delivery of social and economic infrastructure or through contracted delivery of public programs and services. Withers describes the ‘partnership between market, state and community in the provision of the foundations of national life [as] the key to the Australian Way in the institutional construction of the nation’.[12]

How big should the public sector be?

The size and role of the public sector are logically interdependent. In practice, however, the two issues are often separated, particularly in criticisms of how much governments are spending. Consequently, the size and cost of the public sector is often controversial, even though actual employee numbers have been stable for many years. The appropriate size of the public sector is regularly tested through reviews conducted by Commonwealth, state and territory governments, particularly when incoming governments argue ‘the financial cupboard is bare’.[13] Reductions in the public sector at all three levels of government frequently occur in response to such reviews and/or to periods of international fiscal crisis. They may take the form of direct cuts, such as ‘razor gang’ reviews that outsource services to the private sector, or result from long-term reforms in governance that aim to keep a check on government size and outlays, such as expenditure review committees, efficiency dividends and employment restrictions.[14]

Criticisms of the public sector’s size, in terms of outlays and staff numbers, are generally based on the effects of government intervention on the economy. These criticisms are generally based on four key considerations:

- why governments are providing services that the public could choose to pay for in the private sector

- the requirement for higher taxation and government borrowing to fund public sector organisations and the goods and services they provide, which may act as a brake on economic growth

- the possibility of ‘crowding out’ – when businesses find it harder to obtain finance to invest because government borrowing increases interest rates, making private borrowing more expensive

- government services are often criticised for being inefficient, such as when Commonwealth and state government responsibilities overlap in particular areas of policy.

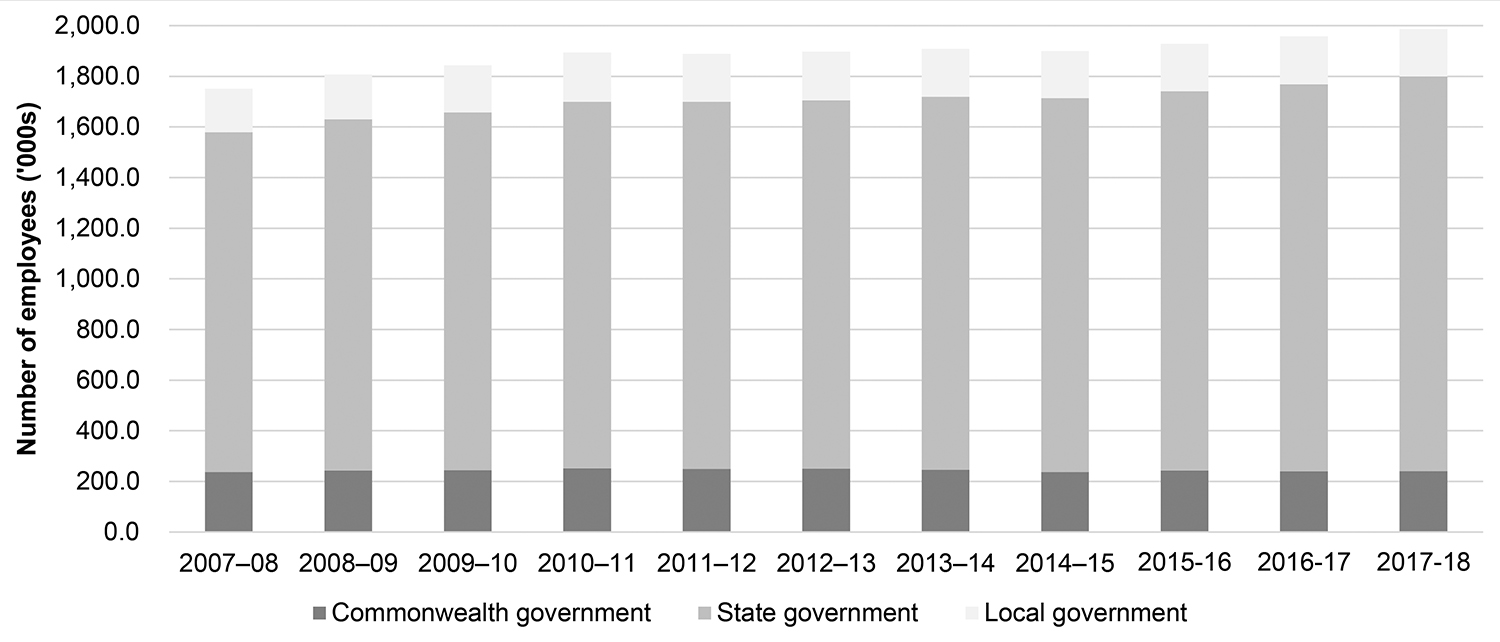

An overview of trends in public sector employment over the past decade is provided in Figure 1. This figure shows that there has been an increase overall in the number of public sector employees, from 1.75 million in 2007–8 to 1.99 million in 2017–18.[15] However, as a proportion of the total workforce, public sector employee numbers declined from 21 per cent in 1990 to 16 per cent by the end of the 1990s, where they have remained, apart from a slight rise in 2007–11. Public sector workers currently constitute 15.5 per cent of the workforce.[16]

The relative proportions of those employed across the three levels of government have also remained stable over the decade. However, the compositions of the Commonwealth and state/territory public sectors are quite different, reflecting the significantly greater role the state and territory public sectors play in direct service delivery to individuals, communities and businesses. Only around one-quarter of the Commonwealth public service works on service delivery.[17] Conversely, the proportion of those in the states and territories working on service delivery tends to be much larger (around 80–85 per cent), with a correspondingly smaller number working on policies for these governments.[18]

At around 36 per cent of gross domestic product (GDP), general government spending in Australia is not large by Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) standards;[19] this proportion has not changed much over the preceding two decades. By themselves, however, statistics on the size of and trends in public sector employment and expenditure tell us very little, compared with how ideas about the appropriate role for governments change over time and are reflected in the public sector’s functions. (We will look at this issue more closely in the next section.)

As we have noted, the vast majority of public sector employees are engaged in direct service delivery, particularly through the education, health and police/justice sectors. This reflects the public’s continuing expectation that ‘the service state’ will provide a range of services directly, as one component in a ‘hybrid mixture of part public, part private activities, delivery chains that do not remain in neat boxes or organisational settings’.[20]

An overview of recent public sector changes

Developments in how the public sector works reflect the way Australians and their elected representatives decide the following questions, and how those answers change over time:

- What are most efficient, effective, equitable and sustainable ways for governments to design and deliver services and programs that respond to the needs and wants of their citizens, businesses and communities?

- How should that response involve the private and not-for-profit sectors, and citizens themselves?

The ‘traditional’ public sector was arguably the dominant model for the public sector in Australia and New Zealand to the end of the 1980s. This model was characterised by a number of features derived from the Westminster tradition, including:

- a politically neutral public service controlled by and accountable to ministers

- government departments that directly provide services, with little outsourcing and competition, integrating policy and operational functions, from the design of policies through to their implementation and delivery ‘at street level’

- in order to perform these functions effectively and efficiently, departments organised in standardised managerial hierarchies in which power and authority are increasingly invested in correspondingly smaller echelons of senior officials (as distinct, say, from markets and networks)[21]

- departments largely designed to implement political directions in discrete, manageable and repetitive tasks, conducted according to prescribed rules and technical expertise.[22]

However, during the 1970s and 1980s, governments were increasingly faced with economic globalisation, demographic pressures, the role of supranational economic and political institutions and concerns about the size and cost of their public sectors. Consequently, they also questioned their capacity to manage these issues through traditional bureaucratic structures and methods.[23] Perceptions that the public service had become ‘a self-contained elite exercising power in the interests of the status quo but without effectively being accountable for its exercise’[24] led to reviews and changes that aimed to restore ministerial control.

The most important set of public sector practices and values that emerged in the 1980s and 1990s is collectively described as the new public management (NPM), and is still highly influential today. NPM aimed to make government more efficient and effective, based on ideas derived from economic theory and business management techniques. Its proponents called for the public sector’s monopoly over policy making and service delivery to be removed or at least reduced. (The Howard government’s minister for administrative services applied a ‘yellow pages’ test: if a business was listed in the business phone directory, the minister argued that there was no reason why it should be provided by government.)[25]

Instead, the NPM’s objectives included giving users more choice in the services they received, making more use of market-type competition, and foreshadowed a program of widespread privatisations and the separation of service delivery agencies from their parent policy departments. They called for a greater focus on financial incentives and transparent performance management in public sector organisation.[26] The classic NPM text Reinventing government[27] coined the phrase ‘steering, not rowing’ to advocate less involvement by the public sector in actually delivering services and more focus on policy making and on the choice and design of such services.[28]

A summary of NPM’s characteristics, such as ‘disaggregation, competition and incentivization’,[29] is provided in Table 1. In practice, NPM was not always adopted for the same reasons and did not always consist of the same policy mix when implemented.[30]

|

Dimensions of change under NPM |

Under older forms of bureaucracy |

Under NPM |

|---|---|---|

|

Organisational disaggregation |

Uniform public service-wide rules; centralised controls over pay and staffing |

Disaggregation of units in the public sector to enhance management and focus accountability; separately managed, corporatised units with delegated control over resources; disaggregation of traditional bureaucratic organisations into commissioning and delivering agencies, the latter related to the ‘parent’ by a contract or quasi-contract |

|

More competition in the public sector |

Public service organisations have semi-permanent roles; unified organisational chains of delivery and responsibility |

More use of contracts and outsourcing; competition within the public sector and with the private sector |

|

Adoption of private-sector management practices |

Emphasis on a distinctive ‘public service ethic’, particularly its non-pecuniary value set, permanency and standard national pay and conditions; citizens and businesses seen as clients and beneficiaries |

Adoption of private-sector reward systems, greater flexibility in hiring and rewards; term contracts, performance-related pay and local determination of pay and conditions; emphasis on service quality; citizens and businesses are rational consumers and therefore ‘customer responsiveness’ is paramount |

|

Discipline and frugality in resource use |

Emphasis on institutional continuity and stable budgets |

‘Doing more with less’: an active search for alternative, less costly ways to deliver public services; reduced compliance burden for business |

|

Hands-on professional management |

Emphasis on ‘mandarins’,[31] with traditional skills in making, but not administering, policy; adherence to rules paramount |

‘Let the managers manage’: highly visible managers wielding discretionary power |

|

Explicit standards and measures of performance |

Qualitative, implicit standards and norms based on trust in a professional public service |

Tangible and reportable performance measures and indicators on the range, level and content of services to be provided; goals, targets and indicators of success, preferably expressed in quantitative terms; greater transparency in resource allocation; adoption of activity- or formula-based funding and subsequently accruals accounting |

|

Greater emphasis on output controls |

Public organisations controlled by top-down ‘orders of the day’, as determined by senior management; emphasis on procedures |

Public organisations controlled through resources and rewards allocated according to pre-set output measures; emphasis on results |

The legacy of NPM

In the 1980s and 1990s, the adoption of NPM policies by both Labor and Liberal–National Coalition governments led to widespread privatisation of government assets and services and commercialisation of many of those remaining in public hands (for instance, some services introduced user charging).[32]

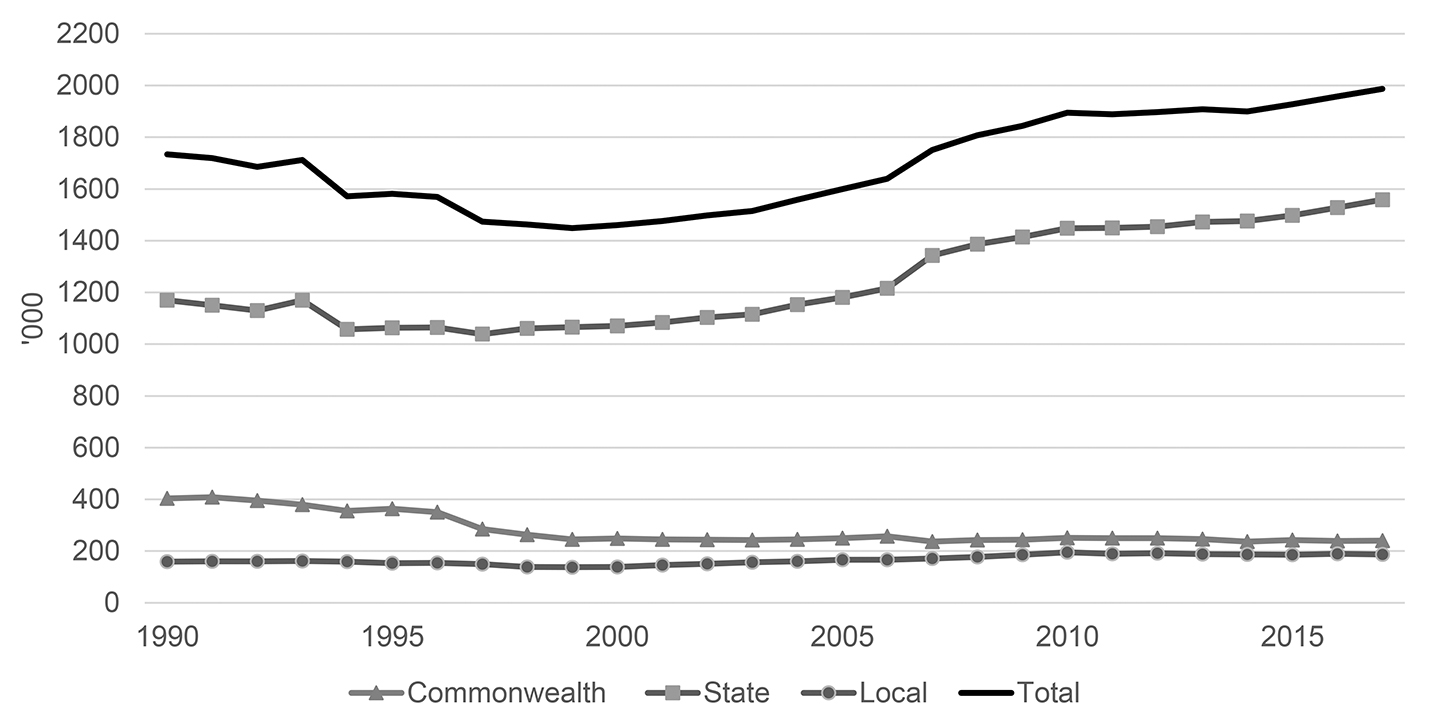

As Figure 2 suggests, the impact on employee numbers during NPM’s heyday was more in the order of a redistribution from the Commonwealth to state and local governments, with only a minor downsizing in total numbers in the 1990s, from 1.73 to 1.45 million, and then an increase to just under 2 million currently.[33] Commonwealth employees declined from 23 to 12 per cent of the total public sector workforce between 1990 and 2017, while the proportion of state government employees rose from 67 to 78 per cent.

The period of NPM largely replaced the highly centralised state, with its monopoly over policy design and delivery, with a new set of relationships between government and other societal sectors and players. These relationships gave governments a choice between traditional delivery via public sector organisations, market and quasi-market approaches, and networks,[34] and hence greater flexibility in responding to the demands and expectations of citizens, who had been given choice and agency as ‘customers’ by NPM.

By the mid-2000s, NPM was losing its status as the predominant paradigm for public sector organisation. Key elements of NPM had been reversed or stalled, amidst concerns about the fragmentation of the public sector and its services and loss of accountability and capability summed up as ‘the hollowed-out state’.[35] Criticism of NPM highlighted its narrow focus on efficiency and its implication that ‘the public nature of what governments do is not particularly important’.[36]

Indeed, NPM’s emphasis on ‘management’ appeared to some analysts to ignore the profound economic and social changes that had given rise to public sector reform in the first place. These developments required more fundamental changes to how political institutions and public expectations interacted and were managed.[37]

Nevertheless, many elements of NPM are still in place, such as performance management and budgeting and market-based competition for some services. The introduction of market-style mechanisms to procure services via competitive tendering processes led to greater co-option of the not-for-profit sector in delivering public policies. The latter is now a major partner of the public sector, to an extent, Alford and O’Flynn argue, that ‘would have been unrecognizable’ forty years ago.[38]

Beyond new public management

No single paradigm of public sector reform has emerged to dominate the early decades of the new century in the way NPM dominated the closing decades of the last. Instead, a number of influential and interrelated directions are emerging that respond to, and in some cases reverse, NPM’s main tenets.

A new model of public sector organisation that Osborne and others have called the ‘new public governance’ recognises that the complexity of citizens’ needs is not well handled by NPM’s separation of policy and service delivery agencies and widespread adoption of contractual service delivery through the private and not-for-profit sectors.

The ‘whole of government’, collaborative and customer-centric approach that reponds to these problems forms part of a broader movement towards the new public governance. This is characterised by the public sector working in partnership and through networks with other sectors to deliver public services, on the one hand, and multiple processes allowing for input from interest groups, citizens and stakeholders to inform policy making, on the other.[39] This pluralistic model encompasses the concept of ‘co-production’,[40] in which policy making and delivery is managed and governed not only by professional and managerial staff in public agencies but also by citizens and communities.[41]

Digital era governance harnesses new technologies in service delivery, administration and communications and the use of social media by bureaucrats and the public for policy input and service delivery. Proponents of digital era governance are critical of NPM’s tendency to encourage, as they see it, ‘management attitudes obsessed with intermediate organizational objectives rather than service delivery or effectiveness’.[42] Advocates argue that information technology is transforming the relationship between governments, bureaucracies and the public through the reintegration of public services; needs-based, simpler and more agile whole-of-client service delivery; and the generation of greater productivity through digitisation.[43]

Public value governance (PVG), the third dominant model of public sector organisation and development, is less about the means by which governments govern. Rather, it focuses more on the political and institutional processes by which public values are identified and inform strategy making, performance management and innovation.[44] One of PVG’s most notable advocates argues that the public sector creates public value in two ways: first, by producing goods and services that have been prioritised by the political system, and second, by establishing and operating institutions that are ‘fair, efficient and accountable’, meeting the expectations of citizens (and their representatives).[45]

PVG requires public sector managers to do three things: help to identify and define the public interest; secure support for the creation of new public goods and services from political and other stakeholders (such as interest groups, clients, businesses and the general community); and obtain the operational and administrative resources required for the task.[46]

Public sector values

No discussion of the public sector is complete without examining the distinctive set of values and norms that guide its work. It may be useful to think of such public sector values in terms of why the public sector exists, what it does and how it does this. Longstanding political and cultural conventions and traditions (derived from both the Westminster model and the federal system) provide the public sector with a purpose and justification for its services to the community.

The values that inform what the public sector should do or produce at any time reflect culturally embedded ‘outcomes values’,[47] such as ‘growth’ or ‘diversity’, that dominate political debate over long periods but do change from time to time. For example, NPM valued private-sector delivery, while cutbacks to welfare programs reflected higher values being attributed to private, as opposed to collective, solutions to income inequality. These values inform the immediate policy priorities of incumbent governments and serve as evaluation standards or design guides for particular policies.[48]

A third set of values, often and explicitly linked to the Westminster tradition,[49] guides how the public sector carries out its tasks and is managed. These values apply both to public servants’ personal conduct and to their organisations’ work as a whole. They may be expressed as rules about responsiveness, impartiality, procedural fairness, efficiency and ethical behaviour, but may also (controversially) extend to how public servants should engage with social media.[50] These values are generally set out in enforceable values statements and codes of conduct, which frequently form part of the relevant public service legislation.

NPM reforms led to some important changes to the relationship between public servants and ministers. In the Westminster system, this relationship had been characterised by permanent careers, particularly for senior public servants, impartial support for the government of the day and a degree of anonymity that allowed public servants to advise their political masters freely.[51] In the 1980s, these arrangements changed in a number of Western democracies, including Australia and New Zealand. Department heads were placed on limited contracts that were subject to performance appraisal, and the anonymous role of confidential ministerial adviser was weakened as special ministerial advisers and private consultancies played an increasing role in advising on developing policy.[52]

Conclusions

The present context of economic, demographic, social and technological disruption is generating calls for a profound rethinking of the public sector’s purpose, dimensions and approaches, in Australia and internationally. Such debates, informed by the values we have identified above, are integral to the very nature of the public sector. As Jocelyne Bourgon, a leading Canadian public servant and public service innovator, sums it up, the task is ‘to rediscover the irreplaceable contribution of the state to a well-performing society and economy and articulate a concept of that state adapted to serving in the twenty-first century’.[53] As we have shown, questions about the nature of that task, how it is to be performed and by whom, remain constant for citizens, governments, and for those, like you, who are studying the public sector:

- What do citizens and their communities want and need?

- What role should governments play in responding?

- What are most efficient, effective, equitable and sustainable ways for governments to design and deliver that response?

- How should that response involve the private and not for profit sectors, and citizens themselves?

- What capacity will governments and their public administrations need to carry out this work, and what values will the public sector need to display and champion?

References

Alford, John (2008) The limits to traditional public administration, or rescuing public value from misrepresentation: debate. Australian Journal of Public Administration 67(3): 357–66. DOI: 10.1111/j.1467-8500.2008.00593.x

Alford, John, Jean Hartley, Sophie Yates and Owen Hughes (2017). Into the purple zone: deconstructing the politics/administration distinction. American Review of Public Administration 47(7): 752–63. DOI: 10.1177/0275074016638481

Alford, John, and Janine O’Flynn (2012). Rethinking public service delivery: managing with external providers. Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

—— (2009). Making sense of public value: concepts, critiques and emergent meanings. International Journal of Public Administration 32(2): 171–91. DOI: 10.1080/01900690902732731

Alonso, José, Judith Clifton and Daniel Díaz-Fuentes (2015). Did new public management matter? An empirical analysis of the outsourcing and decentralization effects on public sector size. Public Management Review 17(5): 643–60. DOI: 10.1080/14719037.2013.822532

Aulich, Chris, and Janine O’Flynn (2007). From public to private: the Australian experience of privatisation. The Asia Pacific Journal of Public Administration 29(2): 153–71. DOI: 10.1080/23276665.2007.10779332

Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) (2018). Employment and earnings, public sector, Australia, 2017–18. Cat. No. 6248.0.55.002. Canberra: ABS.

—— (2017). Labour force, Australia, June. Canberra: ABS.

—— (2015). Australian system of government finance statistics: concepts, sources and methods. Canberra: ABS.

Australian Public Service Commission (2018). APS employment data 30 June 2018 release. www.apsc.gov.au/aps-employment-data-30-june-2018-release

Bevir, Mark, and R.A.W. Rhodes (2011). The stateless state. In Mark Bevir, ed. The Sage handbook of governance. London: Sage Publications.

Bourgon, Jocelyne (2017). Rethink, reframe and reinvent: serving in the twenty-first century. International Review of Administrative Sciences 83(4): 624–35. DOI: 10.1177/0020852317709081

Bozeman, Barry, and Japera Johnson (2015). The political economy of public values: a case for the public sphere and progressive opportunity. American Review of Public Administration 45(1): 61–85. DOI: 10.1177/0275074014532826

Butcher, John, and David Gilchrist (2016). The three sector solution: delivering public policy in collaboration with not-for-profits and business. Canberra: ANU Press.

Caiden, Gerald (1967). The Commonwealth bureaucracy. Carlton, Vic.: Melbourne University Press.

Commonwealth of Australia (2018). Budget paper 1: budget strategy and outlook. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia. https://archive.budget.gov.au/2018-19/

Denhardt, Janet, and Robert Denhardt (2015). Public administration and the new public management. In Janet Denhardt and Robert Denhardt, eds. The new public service: serving, not steering. New York: Routledge.

Dunleavy, Patrick, Helen Margetts, Simon Bastow and Jane Tinkler (2006). New public management is dead: long live digital-era governance. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 16(3): 467–94. DOI: 10.1093/jopart/mui057

Fabian, Mark, and Robert Breunig, eds. (2018). Hybrid public policy innovations: contemporary policy beyond ideology. New York: Routledge.

Goldring, John (1980). Accountability of Commonwealth statutory authorities and ‘responsible government’. Federal Law Review 11(4): 353–85. DOI: 10.1177/0067205×8001100401

Greve, Carsten (2015). Ideas in public management reform for the 2010s: digitalization, value creation and involvement. Public Organization Review 15(1): 49–65. DOI: 10.1007/s11115-013-0253-8

Halligan, J. (2007). Reintegrating government in third generation reforms of Australia and New Zealand. Public Policy and Administration 22(2): 217–38. DOI: 10.1177/0952076707075899

Hood, Christopher (2000). Relationships between ministers/politicians and public servants: public service bargains old and new. In B. Guy Peters and Donald J. Savoie, eds. Governance in the twenty-first century: revitalizing the public service. Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press.

—— (1995). The ‘new public management’ in the 1980s: variations on a theme. Accounting, Organizations and Society 20(2–3): 93–109. DOI: 10.1016/0361-3682(93)E0001-W

—— (1991). A public management for all seasons? Public Administration 69: 3–19. DOI: 10.1111/j.1467-9299.1991.tb00779.x

Hood, Christopher, and Martin Lodge (2006). The politics of public service bargains: reward, competency, loyalty – and blame. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press.

Horne, Nicholas (2012). The Commonwealth efficiency dividend: an overview. Parliamentary Library Research Publications. Canberra: Parliament of Australia. https://www.aph.gov.au/About_Parliament/Parliamentary_Departments/Parliamentary_Library/pubs/BN/2012-2013/EfficiencyDividend

Hughes, Owen (2003). Public management and administration: an introduction, 3rd edn. Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

Kettl, Donald (2000). The global public management revolution: a report on the transformation of governance. Washington DC: Brookings Institution Press.

Mazzucato, Mariana (2016). From market fixing to market-creating: a new framework for innovation policy. Industry and Innovation 23(2): 140–56. DOI: 10.1080/13662716.2016.1146124

—— (2013). Entrepreneurial state: debunking public vs. private myths in risk and innovation. London; New York: Anthem Press.

Meijer, Albert (2016). Co-production as a structural transformation of the public sector. International Journal of Public Sector Management 29(6): 596–611. DOI: 10.1108/IJPSM-01-2016-0001

Moore, Mark (2014), Public value accounting: establishing the philosophical basis. Public Administration Review 74(4): 465–77. DOI: 10.1111/puar.12198

—— (1995). Creating public value. strategic management in government. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Nabatchi, Tina, Alessandro Sancino and Mariafrancesca Sicilia (2017). Varieties of participation in public services: the who, when, and what of co-production. Public Administration Review 77(5): 766–76. DOI: 10.1111/puar.12765

O’Faircheallaigh, Ciaran, John Wanna and Patrick Weller (1999). Public sector management in Australia: new challenges, new directions. Brisbane: Macmillan Education Australia.

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) (2018). General government spending. https://data.oecd.org/gga/general-government-spending.htm

Osborne, David, and Ted Gaebler (1992). Reinventing government: how the entrepreneurial spirit is transforming the public sector. New York: Addison-Wesley Publishing.

Osborne, Stephen (2010). The new public governance? Emerging perspectives on the theory and practice of public governance. London: Routledge.

Parker, R. (1978). The public service inquiries and responsible government. In Rodney Smith and Patrick Weller, eds. Public service inquiries in Australia. St Lucia: University of Queensland Press.

Peters, B. Guy (2017). Management, management everywhere: whatever happened to governance? International Journal of Public Sector Management 30(6–7): 606–14. DOI: 10.1108/IJPSM-05-2017-0146

Peters, B. Guy, and John Pierre (1998). Governance without government? Rethinking public administration. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 8(2): 223–43. DOI: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jpart.a024379

Pollitt, Christopher (2002). The new public management in international perspective: an analysis of impacts and effects. In Kathleen McLaughlin, Ewan Ferlie and Stephen Osborne, eds. New public management: current trends and future prospects. London: Routledge.

—— (1995). Justification by works or by faith? Evaluation 1(2): 133–54. DOI: 10.1177/135638909500100202

Pollitt, Christopher, and Geert Bouckaert (2011). Public management reform: a comparative analysis – new public management, governance, and the neo-Weberian state. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Productivity Commission (2010). Contribution of the not-for-profit sector. Research Report. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia.

Quirk, Barry (2018). Empathy, ethics and efficiency: twenty-first-century capabilities for public managers. In Helen Dickinson, Catherine Needham, Catherine Mangan and Helen Sullivan, eds. Reimagining the future public service workforce. Singapore: Springer.

Rainey, Hal (2014). Understanding and managing public organizations. San Francisco: John Wiley & Sons.

Rhodes, R.A.W. (2005). Australia: the Westminster model as tradition. In Haig Patapan, John Wanna and Patrick Weller, eds. Westminster legacies: democracy and responsible government in Asia and the Pacific. Sydney: UNSW Press.

Rhodes, R.A.W., and John Wanna (2007). The limits to public value, or rescuing responsible government from the platonic guardians. Australian Journal of Public Administration 66(4): 406–21. DOI: 10.1111/j.1467-8500.2007.00553.x

Rhodes, R.A.W., John Wanna and Patrick Weller (2008). Reinventing Westminster: how public executives reframe their world. Policy and Politics 36(4): 461–79. DOI: 10.1332/030557308X313705

Simon, Herbert (1998). Why public administration? Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 8(1): 1–11. DOI: 10.4079/pp.v20i0.11779

Stewart, Jenny (2009). Public policy values. Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

Stoker, Gerry (2006). Public value management: a new narrative for networked governance? American Review of Public Administration 36(1): 41–57. DOI: 10.1177/0275074005282583

United Nations, European Commission, International Monetary Fund, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development and World Bank (2009). System of national accounts 2008. New York: United Nations.

Wanna, John, John Butcher and Benoît Freyens (2010). Policy in action: the challenge of service delivery. Sydney: UNSW Press.

Wanna, John, and Patrick Weller (2003). Traditions of Australian governance. Public Administration 81(1): 63–94. DOI: 10.1111/1467-9299.00337

Weight, Daniel (2014). Budget reviews and Commissions of Audit in Australia. Parliamentary Library Research Paper (2013–14). Canberra: Parliament of Australia. https://www.aph.gov.au/About_Parliament/Parliamentary_Departments/Parliamentary_Library/pubs/rp/rp1314/CommOfAudit

Wilson, Woodrow (1887). The study of administration. Political Science Quarterly 2(2): 197–222. DOI: 10.2307/2139277

About the authors

Isi Unikowski worked for three decades in the Australian public service in a variety of central and line departments and agencies, including the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet, the Australian Public Service Commission, the Departments of Social Security and Climate Change, Centrelink and others. He is currently in the final year of a PhD candidacy at the Crawford School of Public Policy at the Australian National University (ANU), conducting research on the practice of intergovernmental management.

John Wanna is the foundation professor of the Australia and New Zealand School of Government (ANZSOG) based at ANU. Previously, he was professor of politics at Griffith University, and he currently holds a joint appointment with Griffith and ANU. He also serves as the national director of research and monograph publications for ANZSOG (with 55 titles produced to date). He has been engaged in research on the public sector in Australia since the 1970s and has many publications on public policy, public management, government budgeting and federalism. He has written over 50 books in the field, and over 100 journal articles and book chapters, and regularly writes the political chronicle for the federal government in the Australian Journal of Politics and History.

- Wilson 1887, 200. Woodrow Wilson was an accomplished practitioner of public administration. ↵

- Unikowski, Isi, and John Wanna (2024). The public sector. In Nicholas Barry, Alan Fenna, Zareh Ghazarian, Yvonne Haigh and Diana Perche, eds. Australian politics and policy: 2024. Sydney: Sydney University Press. DOI: 10.30722/sup.9781743329542. ↵

- Simon 1998, 2. ↵

- Parker 1978, 349. ↵

- Rhodes 2005. The risk of politicisation, or even the appearance of such, has become greater in the age of social media and the erosion of traditional public servant anonymity. The changing ways in which public officials engage with the distinction between ‘politics’ and ‘administration’ and the blurring between them is explored in Alford et al. 2017. ↵

- O’Faircheallaigh, Wanna and Weller 1999, 87. ↵

- ABS 2015. ↵

- Goldring 1980, 355. ↵

- ABS 2015; United Nations et al. 2009. ↵

- That is, organisations that are neither commercial nor government bodies, do not earn profits for their members and perform a range of charitable purposes. ↵

- Productivity Commission 2010, 300. ↵

- Fabian and Breunig 2018, 236 (emphasis in original). ↵

- Weight 2014, 5. ↵

- At the Commonwealth level, an efficiency dividend that reduces funding for departmental expenses by a factor of between 1 and 4 per cent based on assumed productivity increases has been in place for 30 years (Horne 2012, 2). ↵

- ABS 2018. ↵

- ABS 2017. ↵

- Australian Public Service Commission 2018. ↵

- Data sourced from state government workforce statistics. ↵

- OECD 2018. Commonwealth government outlays alone represent around 25.4 per cent of GDP (Commonwealth of Australia 2018). ↵

- Wanna, Butcher and Freyens 2010, 31. ↵

- Osborne 2010, 8. ↵

- Stoker 2006, 45. ↵

- Other potential explanations of NPM point to more endogenous developments within bureaucracies themselves, such as the impact of new technologies that allowed work to be refashioned along private sector lines. ↵

- Royal Commission on Australian Government Administration (1976), quoted in Wanna and Weller 2003, 87. ↵

- Aulich and O’Flynn 2007, 160. ↵

- Hood 1991, 5. ↵

- Osborne and Gaebler 1992. ↵

- Denhardt and Denhardt 2015, 11; Osborne and Gaebler 1992, 32; Pollitt 2002, 276. ↵

- Dunleavy et al. 2006. ↵

- Dunleavy et al. 2006; Hood 1995; Pollitt 2002; Pollitt 1995. ↵

- ‘An efficient body of permanent officers … possessing sufficient independence, character, ability and experience to be able to advise, assist, and to some extent influence those who are from time to time set over them’ (from the Northcote-Trevelyan Report, quoted in Caiden 1967, 383). ↵

- Aulich and O’Flynn 2007; O’Faircheallaigh, Wanna and Weller 1999, 66. See Hughes 2003 for an extended discussion of the rationale for and against the establishment of public enterprises as a particular segment of the public sector. ↵

- It is similarly unclear whether outsourcing had a significant effect on public sector expenditure and employment in other countries (e.g. Alonso, Clifton and Díaz-Fuentes 2015, 656). ↵

- Peters and Pierre 1998. ↵

- Bevir and Rhodes 2011; Dunleavy et al. 2006, 468. ↵

- Peters 2017, 607. See Halligan 2007 for a discussion of the particular causes of departure from and reaction to NPM by governments and bureaucracies in Australia and New Zealand. ↵

- Kettl 2000. See Pollitt and Bouckaert 2011, 15 for an overview of the difficulties involved in assessing the impact of NPM and its successors. ↵

- Alford and O’Flynn 2012, 8; Butcher and Gilchrist 2016, 5. ↵

- Greve 2015, 50; Osborne 2010, 9. ↵

- Or, in some views, has led to its revival as a cost-cutting aspect of NPM (Nabatchi, Sancino and Sicilia 2017, 767). ↵

- Meijer 2016. Although not untroubled, the introduction of Australia’s ‘My Health Record’ and the role of the Australian Capital Territory’s Citizen’s Jury in devising a new Compulsory Third Party Insurance Scheme are contemporary examples of such co-production. ↵

- Dunleavy et al. 2006, 471–2. ↵

- Dunleavy et al. 2006, 480; Greve 2015, 51. ↵

- Rainey 2014, 64; Greve 2015, 50. ↵

- Moore 2014; Moore 1995, 53. See also Mazzucato’s work on the state’s contribution to public value through its role in creating and supporting private markets and innovation (Mazzucato 2016; Mazzucato 2013). ↵

- Alford and O’Flynn 2009, 173. You may be interested in the debate between Rhodes and Wanna (2007) and Alford (2008) on whether this role is compatible with the Westminster tradition of ministerial responsibility. ↵

- Stewart 2009, 27. ↵

- Bozeman and Johnson 2015, 63. ↵

- Rhodes, Wanna and Weller 2008, 469. ↵

- Quirk 2018, 104; Stewart 2009, 29. ↵

- Hood and Lodge 2006. ↵

- Hood 2000. ↵

- Bourgon 2017, 625. ↵