17 Tasmania

Dain Bolwell; Lachlan Johnson; Mike Lester; and Richard Eccleston

Key terms/names

accord, blockade, franchise, Hare–Clark, ‘Howard battlers’, House of Assembly, hung parliament, hydro-industrialisation, Legislative Council, lutruwita, minority government, palawa, quota

Although Tasmania is a natural Labor state, there are increasing institutional and political challenges to traditional Labor dominance.[1] Tasmania’s politics are profoundly affected by a sense of economic fragility and the consequent influence of large industries. It has been both a national and global focus for environmental politics and originated the world’s first green political party. Tasmania’s voting system is unique, as are the electoral arrangements for both its houses of parliament. As part of the Australian federation, it is represented by 12 senators, the same number as other states.

Since European settlement, Tasmania has had an export-oriented economy relying heavily on a few key industries for income and employment. Most notable among these have been agriculture; fishing; mining; forestry; mineral processing; and, more recently, tourism and education. Due to its small scale, narrow industrial base and limited per capita income,[2] Tasmania relies on transfers from the Commonwealth government to fund essential public services and infrastructure.Historically, Tasmania’s underperforming economy has been a central issue. The resulting push for development of the state’s resources to create jobs has led to many environmental clashes over hydro-electric dams and power stations; logging of native forests; and, more recently, concerns about the location and scale of tourism developments.

Political history

Tasmania’s political history has been shaped by its geography and is defined by six broad eras: Aboriginal settlement; European exploration and convict settlement at the time of the early industrial revolution; the end of convict transportation followed by self-government during the mid-19th century; federation and statehood followed by hydro-industrialisation for much of the 20th century; the rise of the Green movement and the decline of manufacturing from the 1970s; and the rise of tourism and the services sector from the1990s.

Colonisation

Tasmania, known as lutruwita[3] by its Indigenous inhabitants, the palawa people, was first settled around 40,000 years ago when there was a land connection with the Australian mainland due to lower sea levels during the last Ice Age. Subsequently isolated by rising sea levels some 8000 years later,[4] there were nine tribes spread throughout the area. However, immediately before European settlement, the palawa population was estimated at fewer than 15,000.

Located at the south-east of the Australian continent, Tasmania became a waypoint for European explorers of the Pacific who followed the prevailing westerly winds from the Cape of Good Hope in Africa. Early explorers included Abel Tasman, who landed in 1642 and named the area Van Diemen’s Land. Marion du Fresne (1772), Tobias Furneaux (1773), James Cook (1777) and William Bligh (1788 and 1792) all visited subsequently, as did several other French and British explorers.

The first European settlement on the Derwent River in 1803 near present-day Hobart was based partly on fear of French ambition, especially as George Bass and Matthew Flinders had shown in 1798 that Van Diemen’s Land was separate from the mainland and therefore might be distinct from the British claim to New South Wales (NSW).[5] Its usefulness as a jail for convicts and political prisoners was also important as it was realised that, as an archipelago of remote islands, escape was almost impossible.[6]

Clashes between the palawa and the first European settlers near modern day Hobart soon escalated into massacre and continuing intercultural violence. the ‘Black War’ (1824–31), the ‘most intense frontier conflict in Australia’s history’, led to the near eradication of the palawa and their culture and the imposition of martial law over a four-year period from 1828–32. Scholars estimate that some 1,000 Aboriginal people and 200 settlers were killed during the conflict,[7] which has since been demonstrated by historians to have been an expressly genocidal project.[8] By 1830 there were 24,000 settlers in Tasmania, but only about 250 Aborigines remained alive.[9]

Expansion of British settlement and progress toward responsible self government

The independent settlement of northern Van Diemen’s Land was established on the Tamar River in 1804 at Launceston, which has since tended to look northward more than the southern capital. In fact, its establishment led to the founding of Melbourne in 1835 by the entrepreneur John Batman, whose party sailed across Bass Strait in the Hobart-built schooner, Enterprize.

The fragility of the isolated southern colony was made stark in 1809, when Governor Bligh from Sydney and Lieutenant-Governor Collins from Hobart Town met after Bligh had been deposed by the Rum Rebellion and subsequently released. Bligh sailed for Hobart Town, where Collins refused to help him re-take his post of governor of NSW, and their relationship further soured when Bligh had one of Collins’ sons, a crewman on his ship, flogged for insubordination.[10] During Bligh’s subsequent vengeful blockade of the Derwent aboard his 12-gun[11] HMS Porpoise, all ships entering the river were ‘taxed’ some of their cargo, which contributed to the fledgling colony’s economic woes. After several months, Bligh eventually returned to Sydney upon hearing that that a new governor, Lachlan Macquarie, had been appointed from England.

The Van Diemen’s Land economy grew based on fertile plains between Hobart and Launceston suitable for sheep and cropping, at a time when Sydney settlers had not established farms beyond the Blue Mountains.[12] Shipbuilding, timber and whaling were flourishing industries throughout the 1800s, and much timber and whale oil were exported. During the first few decades of the 19th Century, more ships were built in Van Diemen’s Land than in the rest of the Australian Colonies combined.[13]

After an 1823 Act of the British Parliament separated Van Diemen’s Land from NSW, the Legislative Council was established in 1825 to advise the Lieutenant Governor. It consisted of six members chosen by him, expanding to 15 members in 1828. By 1851 it had 24 members, of whom 16 were elected. Consistent with similar jurisdictions, only men over 30 who owned a certain amount of property were eligible to vote. The colony’s value as a remote jail faded as the local economy developed.

Until transportation ceased in 1853, nearly half of all convicts throughout the Australian colonies had been sent to Van Diemen’s Land – a state of affairs that was increasingly resented by the resident populace.[14] The end of transportation followed the formation of an Anti-Transportation League supported by all elected members of the Legislative Council. Many former convicts found their way to Victoria, lured by the gold rush of the 1850s as labour was then in strong demand. This brought about depopulation and economic stagnation in the southernmost settlements.

Federation to the present day

The global depression of the 1890s affected Tasmania’s export-based economy significantly, and there was considerable support for combining in a federation with other colonies and the promise of greater interstate trade that would follow. In the first referendum of 1898, Tasmanians voted overwhelmingly in favour of federation with a more than 81 per cent ‘yes’ vote. At the second (1899) referendum the vote was even higher at nearly 95 per cent in favour. Both results were the highest of any jurisdiction, considerably higher than NSW where fear of a loss of influence saw ‘yes’ votes of 52 and 57 per cent respectively.[15] Clearly, Tasmanians thought they would benefit from closer economic relations with the wealthier mainland states.

During the 20th century, Tasmania was much affected by global convulsions and electoral volatility increased, although the Labor Party was dominant for most of the period.[16] From a population of just over 200,000 people, Tasmania sent more than 15,000 to the First World War. Nearly 2,900 died and about double that number returned wounded. There were fewer casualties in the Second World War, but still about 4,000 in total.12 The state’s key economic transformation, hydro-industrialisation, enabled electricity generation from dams, largely in the remote central highlands. Said to be inspired by a visit of then-prominent farmer and industrialist Walter Lee (who would later serve as Tasmania’s Premier) to the pre-war German Ruhr Valley where the economy was booming, the Tasmanian Hydro-Electric Department (later the Commission or HEC) was created from private companies in 1914 and continued dam building until the 1980s. Industries attracted to the state as a result included paper, chocolate, zinc and aluminium production, as well as wool and carpet mills throughout the state.

However, the HEC’s decision to flood the iconic Lake Pedder in the state’s southwest so horrified a growing number of conservation-minded Tasmanians that it led to the creation of the world’s first green political party in 1972, the United Tasmania Group, later the Tasmanian Greens and subsequently the Australian Greens. Lake Pedder was flooded but a later attempt to dam the Franklin River in the early 1980s led to global protests, a blockade and the intervention of the federal government backed by the High Court to prevent the dam being constructed.

The Franklin River dispute marked the end of the hydro-industrialisation strategy and confirmed the importance of tourism-related industries to the state as large-scale manufacturing employment continued to decline. A legacy of the dam building period is that Tasmania has Australia’s highest level of renewable energy production at 93 per cent and is poised to export more renewable electricity to mainland Australia.[17] During the 1990s, tourism marketing and air and sea access were improved, leading to a strong increase in visitor numbers and making the tourism and hospitality industries key drivers of economic growth. Tourism, along with Tasmania’s growing ‘clean and green’ natural produce, has led also to strong growth in the food and beverages industries both for local consumption and export. The 2014 visit of Chinese President Xi Jinping boosted Tasmania’s appeal in Asian export markets for agricultural products and as a tourism destination for his compatriots. By 2017 tourism accounted for 10.4 per cent of Tasmania’s economic output and 15.8 per cent of total employment – compared with national averages of 6.3 per cent and 7.7 per cent respectively.[18] Politically, the rise of the Greens on the left of the Labor Party changed the complexion of representative politics in Tasmania as well as nationally.

Key institutions and actors

Tasmania’s political practice has several distinctive features, which have evolved over time contributing to a unique political culture. The relationship between electoral systems and the success of political parties has been long studied, and Tasmania is an interesting case study in this regard.[19] Tasmania (like the ACT) is unusual in using a proportional electoral system to elect its lower house, having five electorates each of five seats for a House of Assembly (lower house) of 25 members. The Legislative Council (upper house) consists of 15 single-member electorates. This multi-member lower house and single-member upper house is the inverse of all other state electoral systems.

Elections and voting

The ‘Hare–Clark’ electoral system, used in Tasmania since 1909, allows independents and minor parties to secure representation in the House of Assembly more easily. In the 34 elections since it was introduced, independents or minor parties have won seats in all but nine. In two of those nine where no independent was elected, Labor and the Liberal Party each won 15 seats. Since 1989, when five Greens were elected to the House of Assembly, Tasmania has had four ‘hung’ parliaments which resulted in minority governments. It is fair to say all Tasmania elections are close and there has been a long-running argument about the prospects and benefits – or otherwise – of majority government.

By-elections are rare and casual vacancies are normally filled by recounting the votes of the retiring member in that division from the preceding election. While all other states and territories have fixed four-year terms for their house of government, Tasmania alone has a maximum four-year term.

The House of Assembly

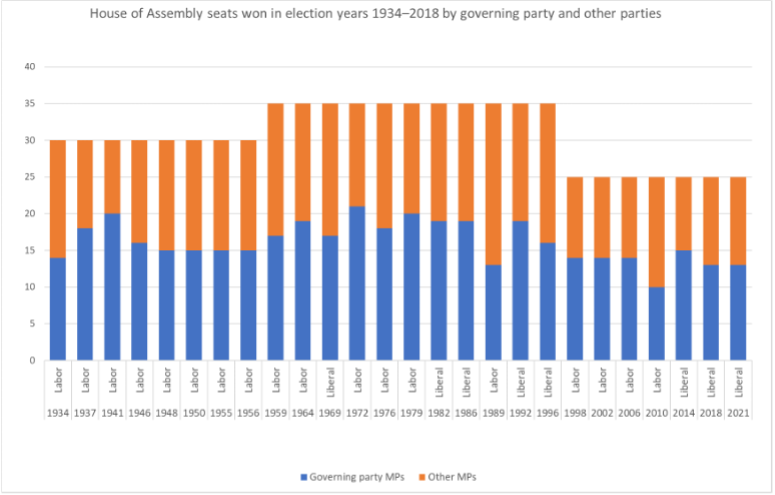

The number of members in the House of Assembly has changed over time, having had at least 30 members since its origins in 1856 – until 1998 when it was reduced from 35 to 25, as shown in Figure 1 below. This arose as a productivity offset to justify a controversial 40 per cent pay rise for MPs as a reaction to union and public pressure at a time of austere state budgets and restrictions on public sector pay rises. But it especially suited the two major parties, which saw it as a chance to make life harder for the Greens by lifting the quota required to win a seat from 12.5 per cent (one eighth) to 16.7 per cent (one sixth). A quota under Hare–Clarke is the total number of votes divided by the total number of seats per electorate plus one, plus one vote.[20]

In 2022 the Expansion of House of Assembly Bill was passed by the Parliament, restoring the number of MPs in the House of Assembly to the pre-1998 level of 35 with seven members being elected from each of the five electorates and the quota to win a seat back to 12.5 per cent for the next election due before Saturday 28 June 2025.

The Legislative Council

The nearly 200-year-old upper house – the Legislative Council – was reconstituted as part of the bicameral parliament in 1856. Along with the House of Assembly, its size was reduced in 1998 – from 19 down to 15 seats, based on single-member electorates. Several distinctive characteristics of the Tasmanian Legislative Council mark it as among the most powerful upper houses in the ‘Westminster’ parliamentary world. For example, the Tasmanian Constitution Act 1934 includes no provisions for dissolving the upper house. It therefore retains the highly unusual ability to reject appropriation bills and thus send the lower house to an election without having to face the polls itself. This curious feature of led to a minor constitutional crisis in 1879, when the Legislative Council effectively went on strike and refused to sit for three months, unable to be brought to heel by the Governor.[21]

Further, elections for its single-member divisions are staggered. Members are elected for six-year terms with elections alternating between three divisions in one year and two divisions the next. This quirky electoral system means that, unlike other state upper houses and the Senate, the Legislative Council never has to face either a full or half-house general election. Further, it is the only parliamentary chamber in Australia in which, historically at least, most members have been independents and therefore not subject to party control. While most of these independents are politically quite conservative, their autonomous scrutiny of government proposals arguably has value. In recent years, both the Liberal and Labor parties have experienced electoral success in the upper house, but independents still outnumber both parties.

Beyond the two-party system

Tasmania’s Hare–Clark electoral system has allowed emerging social movements to secure parliamentary representation. As a result, significant trends in national party politics including the rise of the Greens, and growing support for the Liberal Party from socially conservative working-class voters – the ‘Howard Battlers’ – was evident in Tasmanian long before other states.

In Tasmania, the Labor and Liberal two-party system[22] generally prevailed at the state level between 1949 and 1982 with continuous Labor governments, occasionally with the support of independents, only disrupted by the one-term minority Liberal government between 1969 and 1972.

By the early 1980s, a proposal to dam the Franklin River became the focus of political debate both in Tasmania and nationally, at a time of high unemployment in the state. The Liberal opposition in Tasmania supported the scheme while the Labor government was torn between maintaining its commitment to industrialisation and the demands of an increasingly vocal and influential green movement who were determined to save the Franklin. The Labor Premier, Doug Lowe, proposed a compromise of damming an alternative river in the south-west wilderness, which would still generate more power for industry but save the Franklin River.

Lowe’s plan failed; he lost the party leadership over the issue and moved to the crossbenches as a Labor independent. The government continued under his successor Harry Holgate, who called an election six months later. The Liberals under Robin Gray subsequently secured a landslide win in the May 1982 election on the back of unprecedented working-class support. In a sign of things to come, leader of the ‘Save the Franklin’ campaign, Bob Brown, who later became leader of the Australian Greens, was elected to the House of Assembly in 1983. By 1989 Green independents were a political force in Tasmania winning five seats in parliament and entering a power sharing ‘accord’ with the Labor Party, enabling them to return to government in 1989.

The following 30 years have seen both majority Labor and Liberal governments, with one period of minority Liberal government and a further term of Labor–Green power sharing between 2010 and 2014. Not only was the Liberal’s 1980s strategy to win working-class votes through a pro-development and jobs platform later echoed nationally, but rivalries between Labor and the Greens for progressive votes in the inner cities were first evident in Tasmania in the same decade.

Cabinet and the ministry

From 1972 until 1998 the Tasmanian government had a maximum of 10 ministers. Following the reduction in the size of parliament in 1998 this has varied up to nine ministers. The change in numbers, introduction of better parliamentary committee systems, and the success of major parties in the Legislative Council has led to more ministers being appointed to Cabinet from the upper house. Since the reduction in the size of parliament, however, there are concerns that there are too few government members from which to draw a Cabinet, too great a workload on ministers, and the potential for administrative conflicts where ministers have too many portfolios.

There is also the danger of too few ordinary MPs to provide effective parliamentary scrutiny of government. As noted by Wettenhall, ‘questions about patterns of relationships between executive governments and legislatures’[23] are common in many small jurisdictions, especially island-states, where there are disadvantages in having few ministers either becoming ‘jacks of all trades’, or in having the jurisdiction essentially run by the bureaucratic administration.

The changing political landscape

We have noted how Tasmania’s narrow industrial base and economic vulnerability have resulted in an economy reliant on a small number of industries. As a result of these concerns, Tasmanian voters have historically supported parties they believe will deliver economic security. For much of the 20th century, Tasmania has had Labor governments, but that changed in 1982 with the election for the first time of a majority Liberal government[24] led by premier Robin Gray, who subsequently held office for two terms. Since then, the Liberals have held government from 1992 to 1998 and again from 2014 to the present.[25] In between, Labor held office for an unbroken period of 16 years (1998 to 2014) with four successive premiers, including Tasmania’s first woman premier, Lara Giddings.

While Tasmania has also experienced three minority governments with the Greens holding a balance of power,[26] there has been a long history of independents or minor parties holding the balance of power.[27] As a report by an advisory committee chaired by A.G. Ogilvie noted in 1984, ‘history has shown independents and minor parties have a tendency to gain representation in a majority of elections’.23 This is facilitated by the Hare–Clark system, which enables candidates to win seats with considerably less than 50 per cent of the vote in multi-member electorates. However, the entry of the Greens to the left of the Labor Party on the back of the conservation debates changed the complexion of representative politics within the state.

Since the early 1980s, the Greens have won up to five seats in some elections but managed only two in each of the 2018 and 2021 elections. Much of the Greens’ electoral success has been at the expense of the Labor Party, which recorded a record low vote of 28 per cent and only seven seats in 2014 and 28.2 per cent again in 2021. In the parliament elected in 2021, the Liberals had 13 seats, Labor 9, and the Greens two, plus one independent in the House of Assembly.

However, the government led by Liberal Premier Jeremy Rockliff was thrown into minority in May 2023 by the shock decision of two of its MPs – member for Bass Lara Alexander and member for Lyons John Tucker – to resign from the party and sit as independents, leaving the Liberal government with 11 members. This change has also marked a significant power shift: for the first time since 1989, the Greens no longer solely hold the balance of power in a minority government but share it with three non-aligned independents and independent Labor member David O’Byrne.[28]

The economy

Traditionally Tasmania’s major industries have been mining, agriculture, fishing and forestry. During the period of hydro-industrialisation, major metal and forest products processing plants were also established in the state. Aquaculture has grown from a relatively small industry in the late 1980s to the point that Tasmania is now a large producer of seafood, particularly salmon. However, the state’s narrow industrial base means that average Tasmanian household income is almost 19 per cent below the national average and, as a consequence, Tasmania is more dependent than other states on GST revenue and other grants from the Commonwealth for the provision of public services and infrastructure.

A reliance on exports, a small number of relatively large processing industries, the vagaries of interstate and overseas transport and reliance on federal transfers have combined to make Tasmania particularly susceptible to downturns in the Australian and international economies. From the late-1990s, improvements to sea and air passenger transport sparked a growth in tourism, which has since become one of the state’s major industries. Education has also grown in importance, attracting more overseas fee-paying students albeit from a relatively low base. One outcome of the decades of debate over forestry, mining and the environment is that some 42 per cent of Tasmania is protected in the World Heritage Area, national parks or other reserves. Tasmania’s natural environment, clean air, and its reputation for excellent food and drink products are key factors in attracting visitors and students to the state. As of 2018, these factors were contributing to strong economic growth and, for the first time in over a decade the Tasmanian economy was outperforming the economies of the mainland states.

Key issues

The much smaller scale of Tasmania’s political system compared with the other Australian states is significant. Another distinctive feature of the island state is its relatively dispersed population. There are three distinctive and competitive regions: Greater Hobart and the south; Launceston and the north-east; and the northwest and west coasts, including Devonport and Burnie. These regions have different industrial bases, economies, needs and expectations. Despite the small size of the state, each region has its own daily newspaper which champions causes for their district. Overlaying this regional structure are the five House of Assembly electorates discussed above, each about the same size in terms of voter numbers and with boundaries drawn around communities of interest. The same electorates also give Tasmania five seats in the House of Representatives and 12 senators in the Australian Parliament, as negotiated under the federation process, primarily by Tasmanian Andrew Inglis Clark, an admirer of the US Constitution.[29]

Pros and cons of a small state

Despite its small population, equal representation in the Senate means its demands cannot be ignored federally. Competition between the regions and the voices of regional representatives at both the state and federal levels has often led to duplication of services and infrastructure where they cannot be justified by size of population alone. The state’s different regional economies have often led to reliance on a small number of key industries or businesses to sustain employment which can give a relatively small number of businesses a stronger voice in the halls of government when lobbying for infrastructure, access to resources or financial assistance.

The state’s smallness creates issues for governing and governance. All political parties at times find it difficult to find capable candidates to fill vacancies. The power of connections and name recognition in a small jurisdiction has seen the establishment of powerful political ‘dynasties’. For example, former Liberal Premier Will Hodgman is the son of former federal and state MP Michael Hodgman, whose father William Hodgman senior was a former president of the Legislative Council. Michael Hodgman’s brother Peter was likewise a member of both the House of Assembly and the Legislative Council. Indeed, but for a two-year break in the mid-1960s, at least one member of the Hodgman family served in the Tasmanian Parliament continuously from 1955 to 2020. On the Labor side, former member for Clark Scott Bacon is the son of former Labor Premier Jim Bacon and the O’Byrne family has contributed three MPs since the mid-twentieth century. Michelle (member for Bass) and David (member for Franklin) O’Byrne are siblings and even served in Cabinet together prior to the party’s defeat at the 2014 election.

Tasmania’s ‘small pond’ causes problems filling positions at all levels of government, from the judiciary to appointments and promotions in the public service to board positions on government business enterprises. Relatively small networks in business and politics means it is hard to find people who have no past affiliations or business associations, which can lead to suspicions of cronyism and nepotism.

More than 95 per cent of Tasmanian businesses are classified as ‘small’.[30] By comparison, some government-owned businesses are big employers and have more financial resources which give them a dominant voice in key policy arenas. The political power of a small number of private-sector business leaders, investors and large (in Tasmanian terms) employers also has been a cause for concern. For example, during the 2018 state election, a high-profile advertising campaign funded by gaming industry lobby groups against a Labor and Greens policy to remove gaming machines from pubs and clubs was both effective and reminiscent of the forest industry campaigns of the 1980s and 1990s.[31] This campaign was likely decisive in returning the government, arguably leaving the Liberals in debt to the gambling industry.27

Fault lines and the future

Historically, the underperformance of Tasmania’s economy is a recurring theme and the subject of numerous inquiries and interventions. The 1997 Nixon report on the Tasmanian economy for the Commonwealth government, for example, noted that ‘economic activity and jobs growth in Tasmania is the worst of all the states’.[32]

Economic resurgence

As we have noted, the Tasmanian economy experienced a period of very strong growth – sometimes described as a ‘golden age’ – from 2014 to 2019. In a speech to the Committee for Economic Development of Australia (CEDA), then-Premier Will Hodgman declared that Tasmania was ‘now a stronger, prouder, more confident place and the economy one of the strongest performing in the country’.[33]

This economic renaissance began in the late 1990s under Labor Premier Jim Bacon with a program called ‘Tasmania Together’ – an attempt to unite people behind a plan to focus on Tasmania’s advantages (its natural attractions, its reputation for excellent produce, the arts) and to instil a sense of confidence in the community. Despite falling victim to irreconcilable differences over forestry, Tasmania Together succeeded in promoting growth in tourism, a turnaround from a net decline in population to growth from both interstate and overseas migrants, and recognition of the importance of education and the arts as important sectors of economic growth. The establishment of the Museum of Old and New Art (MONA) by professional gambler and eccentric entrepreneur David Walsh in 2011, tapped into an international market of cultural tourism and has fostered innovation and creativity across the state. While the economy remains robust, Tasmania was nevertheless felt the impact of economic headwinds and supply chain disruption associated with the COVID-19 pandemic, which affected the tourism industry in particular.

Growing pains and shifting political conflicts

However, the growth in population, migration, tourism and education services that the state has experienced in recent decades has generated its own set of problems. Road infrastructure, particularly in Hobart, has not kept up with the growth in numbers; tourism infrastructure is struggling to cope with increased visitation and increased demand for accommodation has caused housing affordability problems and a rising number of the homeless. In the Hobart rental market, the number of properties suitable for low-income people declined rapidly in 2018 due to the tourism boom and the removal of properties from the long-term market in favour of more profitable short-stay accommodation. Rapidly rising housing prices have also adversely affected the rental market.30

The ongoing struggle between economic development and the environment has defined Tasmanian politics. Struggles such as the fights to save the state’s wild and natural places from development for hydroelectricity in the 1980s and the forestry conflicts of the 1990s and 2000s seem to be abating somewhat. At the same time, however, rapid growth in the visitor economy has led to environmental tension around the location and scale of tourism infrastructure, such as resorts, hotels, a cable car, and encroachment on wilderness areas.

And new struggles are emerging over the expansion of salmon farming and development of wind farms that aim to capitalise on growing demand for green energy to export via undersea cables to mainland states. Tasmanians are also divided on the government’s intention to build a $715 million AFL-standard stadium on Hobart waterfront’s Macquarie Point as part of an agreement with the League for a Tasmanian team, with many arguing the money would be better spent on housing and hospitals.

Conclusions

The central challenge facing Tasmania is whether the island state can exploit its distinctive strengths to achieve sustainable and inclusive economic growth despite the challenges of remoteness and scale. In many ways this is a political challenge as much as an economic one. Ultimately Tasmania’s prosperity will depend on two factors. First, the political challenge involves resolving traditional tensions between progressive environmentalists and more conservative commercial interests. On this front, the outlook is more favourable than it has been for decades given that political conflict over forestry has abated significantly in recent years – though public concerns about aquaculture, tourism and energy generation remain. A second challenge is whether Tasmanians can have the education and skills to capitalise on the transition from an industrial to a service and knowledge-based economy. The concern here is that levels of educational attainment in Tasmania are well below the national average and that growing numbers of businesses complain about shortages of skilled labour.

Tasmania is Australia’s smallest and poorest state. Its isolation, scale and economic challenges have contributed to what is, by Australian standards, a unique political culture. In recent years, Tasmania’s economic performance and outlook have improved significantly, but it remains to be seen whether the ideological and parochial divisions that have afflicted its politics in the past will prevent the island state from realising its full economic and social potential.

References

Anglicare (2018). Rental affordability snapshot. Canberra: Anglicare Australia.

Australian Bureau of Statistics (2021). Socio-Economic Indexes for Areas (SEIFA) Australia. https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/people/people-and- communities/socio-economic-indexes-areas-seifa-australia/latest-release

Australian Electoral Commission (2011). Federation fact sheet 1 – The Referendums 1898–1900. Canberra: Australian Electoral Commission.

Bennett, S. and R. Lundie (2007). Australian electoral systems. Research Paper no. 5, 2007–8. Canberra: Parliament of Australia.

Boyce, J. (2008). Van Diemen’s Land. Melbourne: Schwartz.

Cameron, Patsy (2006). Aboriginal Life Pre-Invasion. In The Companion to Tasmanian History, edited by Alexander, A. Centre for Historical Studies, University of Tasmania. https://www.utas.edu.au/library/companion_to_tasmanian_history/A/Aboriginal life pre-invasion.htm.

Clark, M. (2012). A history of Australia, Vols 1 and 2. Melbourne University Press.

Clements, N. (2014). The Black War: fear, sex and resistance in Tasmania. St Lucia, Qld: University of Queensland Press.

Climate Council of Australia (2014). The Australian renewable energy race: which states are winning or losing? www.climatecouncil.org.au/uploads/ee2523dc632c9b01df11ecc6e3dd2184.pdf

Courtenay, A. (2018). The ship that never was: the greatest escape story of Australian colonial history. Sydney: Harper Collins.

Department of State Growth (2022). Tasmanian Maritime Industry Prospectus 2022. Tasmanian Government. https://www.stategrowth.tas.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0010/273286/Defence_Tasmania_Maritime_Prospectus_Nov_20.pdf.

Eslake, S. (2018). The Tasmania report. Tasmanian Chamber of Commerce and Industry. www.tcci.com.au/Services/Policies-Research/Tasmania-Report

Harman, K. (2018). Explainer: how Tasmania’s Aboriginal people reclaimed a language, palawa kani. The Conversation, 19 July. http://theconversation.com/explainer-how-tasmanias-aboriginalpeople-reclaimed-a-language-palawa-kani-99764

Haward, M. and P. Larmour, eds (1993). The Tasmanian parliamentary accord & public policy 1989–92. Canberra: ANU Federal Research Centre.

Kippen, R. (2014). The population history of Tasmania to Federation. Centre for Health, Melbourne School of Population and Global Health, University of Melbourne.

Knaus, C. and N. Evershed (2019). Gambling lobby gave $500,000 to Liberals ahead of Tasmanian election. Guardian, 1 February. www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2019/feb/01/gamblinglobby-gave-500000-to-liberals-ahead-of-tasmanian-election

Lawon, T. (2014). The Last Man: A British Genocide in Tasmania. London: I. B. Tauris.

Museum of Australian Democracy (2021). Founding Documents: Constitution Act 1855 (Tasmania). https://www.foundingdocs.gov.au/item-sdid-34.html.

Newman, T. (1992). Hare-Clark in Tasmania, representation of all opinions. Joint Library Committee, Parliament of Tasmania. Hobart: Government Printing Office.

Nixon, P. (1997). The Nixon report: Tasmania into the21st century. Hobart: Commonwealth Government.

Parliament of Tasmania (2018). Women Members of Tasmanian State Parliament. Brisbane: University of Queensland Press.

Watson, R. (2015). A Tasmanian tragedy: honour roll of our World War I casualties. Mercury, 19

April.

Wettenhall, R. (2018). A journey through small state governance. Small States & Territories 1(1): 111–28.

Whitson, R. (2018). Tasmanian Greens’ fortunes may be waning but party’s not over, leader Cassy O’Connor says. ABC, 21 December. www.abc.net.au/news/2018-12-21/tasmanian-greens-tofocus-on-rebuilding/10639504

Winfield, R. 2008, British warships in the Age of Sail 1793–1817: design, construction, careers and fates. Barnsley, UK: Seaforth.

About the authors

Richard Eccleston is professor of political science and founding director of the Institute for the Study of Social Change at the University of Tasmania. He publishes in the fields of comparative and international political economy and his recent books include The Dynamics of Global Economic Governance (2013), The Future of Federalism in an Age of Austerity (2017), and Business, Civil Society and the New Politics of Corporate Tax Justice (2018). Richard is also a commentator on Tasmanian politics.

Dr Dain Bolwell is an associate with the Institute for the Study of Social Change. He has extensive experience in several countries in labour and development with the United Nations. He is the author of Governing Technology in the Quest for Sustainability on Earth (2019), as well as To the Lighthouse: towards a global minimum wage building on the international poverty line (2016). He writes for several journals and newspapers on politics and sustainability, including for The Conversation.

Mike Lester is a former political journalist and commentator in Tasmania where he has worked for the ABC, the Launceston Examiner, the Burnie Advocate and the Hobart Mercury. He worked as a political adviser to former Tasmanian Premier Jim Bacon between 1998 and 2002. Mike has run several public relations and media communication businesses. He is currently a PhD candidate researching how the legacies of past government formation and performance effect the formation of subsequent governments in hung parliaments in Australia. Mike has written articles for the Australian Journal of Politics and History and the Australasian Parliamentary Review.

Lachlan Johnson is a research fellow and policy analyst at the Tasmanian Policy Exchange – an applied policy research centre at the University of Tasmania. He has contributed extensively to the TPE’s work on local government reform, climate and energy policy, and labour demography, in addition to publishing research on Australian and international tax. Lachlan completed his PhD on the role of industry networks in regional innovation systems in 2021.

- Eccleston, Richard, Dain Bolwell and Mike Lester (2024). Tasmania. In Nicholas Barry, Alan Fenna, Zareh Ghazarian, Yvonne Haigh and Diana Perche, eds. Australian politics and policy: 2024. Sydney: Sydney University Press. DOI: 10.30722/sup.9781743329542. ↵

- Just over 30 per cent of Tasmanian residents live in areas scoring in the lowest SEIFA Index of Relative Disadvantage quintile nationally – the highest share of any Australian state or territory (ABS 2021). ↵

- The written form of the Tasmanian Aboriginal language, palawa kani, has only lower-case letters following a decision by the Tasmanian Aboriginal Centre to discontinue capitals (Harman 2018). ↵

- Cameron 2006. ↵

- Clements 2014. ↵

- Although in 1834 ten audacious convicts managed to build a boat, commandeer it and sail to Chile (Courtenay 2018). ↵

- Kippen 2014. ↵

- Lawson 2014 ↵

- Clements 2014. ↵

- Clark 2012. ↵

- Winfield 2008. ↵

- Europeans did not find a route across the Blue Mountains west of Sydney until 1813. ↵

- Department of State Growth 2022. ↵

- Boyce 2008. ↵

- Australian Electoral Commission 2011. ↵

- The Labor Party governed Tasmania for 45 of the 48 years between 1934 and 1982, for example, longer than in any other state. 12 Watson 2015. ↵

- Climate Council of Australia 2014, 31–2. ↵

- Eslake 2018. ↵

- See, for example, Bennett and Lundie (2007) on the effects of Hare-Clark in Tasmania. ↵

- Where there is only one seat, the quota is therefore half the number of votes, plus one vote – which is the same as used throughout Australia in all single-member electorates. ↵

- Museum of Australian Democracy 2021. ↵

- The National Party has never achieved state-level representation in Tasmania. ↵

- Wettenhall 2018, 124. ↵

- The Liberal government of Angus Bethune, 1969–72, relied on the support of Centre Party member Kevin Lyons (Haward and Larmour 1993, 1). ↵

- Premier Will Hodgman was re-elected for a second four-year term in March 2018. ↵

- The three hung parliaments with the Greens holding a balance of power were the Field Labor government of the Labor–Green Accord between 1989 and 1992, the Rundle Liberal minority government between 1996 and 1998 and the Bartlett–Giddings Labor government, with two Greens in Cabinet, between 2010 and 14. ↵

- Newman 1992, 198–201. 23 Newman 1992, 98. ↵

- O’Byrne, member for Franklin, resigned from the Parliamentary Labor caucus in 2021 but remains a member of the party. ↵

- The same Clark as in the ‘Hare-Clark’ voting system. ↵

- According to the Department of State Growth (2019). See www.stategrowth.tas.gov.au/about/divisions/industry_and_business_development/small_business. ↵

- See also Knaus and Evershed (2019) on the gambling lobby’s donations to the Liberals ahead of the 2018 state election, totalling 0,000. ↵

- Nixon 1997, v. ↵

- Mercury, 1 December 2017. 30 Anglicare2018, 6. ↵