46 Spaces of public participation in contemporary governance

Carolyn M. Hendriks and Rebecca M. Colvin

Key terms/names

citizen engagement, co-design, collaboration, community consultation, community engagement, community organising, deliberative forums, listening, networks, public participation, self-governance, stakeholder engagement

Introduction

Public participation has become an expected and valued norm in contemporary governance.[1] Understanding and responding to the needs and interests of diverse publics has long been considered a core task for public policy.[2] Yet meaningfully engaging the public in discussions and decisions on public policy is especially challenging in an era of communicative plenty, where there is an abundance of opportunities for political expression both online and offline.[3] Over the past three decades, governments worldwide have been investing heavily in their participatory infrastructure in order to better communicate, engage and ultimately serve the public.[4] Today, many public sector agencies around the world are experimenting with participatory modes of policy making, for example by engaging citizens via digital communication and platforms, in deliberative forums or co-designing public services with end-users.[5] At the same time, diverse publics are finding different ways to ‘reach in’ to public policy and to shape outcomes through various forms of civic action, including advocacy, protesting, consumer boycotts and digital campaigns.

In this chapter we examine various ways that the public participates in contemporary public policy. To be clear, our intention here is not to describe all modes of public participation, nor to provide recipes for how to run effective participatory processes. Instead our goal is to illuminate the diverse ways that the public can engage in and shape public policy. Along the way we touch on some of the democratic ideals motivating participatory modes of governing such as inclusion, deliberation, and listening. Using contemporary examples, we show why participation can generate both opportunities and challenges for public policy.

We begin by clarifying key terms and concepts, including the idea of participatory ‘spaces’. In the subsequent sections we examine three different participatory spaces including ‘invited spaces’, ‘insisted spaces’ and ‘citizen-led governance spaces’. In the final sections we reflect on some of the contemporary challenges facing participatory governance, and point to important future directions.

Public participation in contemporary governance[6]

In the practice and theory of public policy, the term ‘participation’ carries multiple and often contested meanings. For some, participation is understood minimally as a process of informing the community, whereas for others participation refers to a deeper process in which the public and relevant groups engage interactively with an issue to influence decisions. In this chapter we understand participation in a very broad sense to mean involvement or active engagement in a public problem.

The term ‘public’ is equally slippery. Sometimes the term can mistakenly infer a singular and homogenous ‘public’. In practice, contemporary governance engages multiple publics, often different formal and informal social groups that span interests, ideologies and values. In this chapter ‘the public’ includes a range of actors who contribute to, or are potentially affected by, public policy, including pressure groups, businesses, interested individuals, experts and everyday citizens. In other words, the term ‘public’ captures all of these groups together, with recognition of the diversity between publics.

We view public participation in this discussion through the lens of governance, where public policy is understood as an iterative process involving complex networks of state and non-state actors.[7] A governance lens reflects much of the practice of collective problem solving and decision making in contemporary liberal democracies where governments are just one of many actors involved in identifying policy problems, finding policy solutions, and implementing and evaluating public programs.[8] By viewing public participation from the perspective of governance, we shift away from the notion that public participation is something that governments do (or ought to do) at a particular ‘stage’ of the policy process.[9] Instead, governance enables us to appreciate the broad range of participatory opportunities available to members of the public as they engage in and shape public policy. For example, citizens might choose to engage in a participatory forum run by government, join an advocacy group or participate in a social media campaign or protest movement. In this chapter, we consider all these varied modes of engagement – from the constructive and consensual to the more antagonistic and disruptive – as forms of public participation.

To help us navigate our way through this diverse participatory terrain, we use a spatial metaphor to distinguish different arenas of public participation in contemporary governance. The best known of these arenas is invited spaces of participation, to which we now turn.

Invited participatory spaces

Invited spaces are structured participatory opportunities where a group of citizens or stakeholders is invited into formal governance institutions for input, advice and occasionally decision making. Typically invited spaces are instigated by government – for example, an executive agency or local council – but they can also be triggered by non-government organisations (NGOs), service providers or corporations (such as an infrastructure or resource development company). There are diverse reasons that these institutions might seek to invite the public into a particular policy process or issues. For example:

- to meet democratic expectations

- to achieve better policy outcomes

- to aid policy implementation, development and evaluation

- to gather diverse forms of knowledge

- to boost innovation

- to meet legislative requirements

- to build legitimacy

- to overcome polarisation

- to address or avoid value conflict.

In practice, diverse rationales for inviting the public into the policy process often coexist, sometimes in considerable tension.[10] Indeed, competing ideas on the purpose of a participatory process can be the source of considerable politics between instigators of the participatory process and its participants. For example, Haughton and McManus[11] argue that the invited spaces created to engage the public in the development of the ‘WestConnex’ motorway in Sydney may have adopted the language of participation intended to achieve better policy outcomes, but in practice the process did not allow the public to debate or question the project. In the case of WestConnex, political conflict emerged not just about the motorway itself, but also about the divergence between public expectations for participation and how it was experienced.

Invited spaces are typically contained and well-structured arenas of public participation where the rules and scope of engagement are designed in advance. Participatory methods used in invited spaces range from conventional public and advisory processes (such as public submissions, public hearings and meetings, expert panels, stakeholder committees) through to collaborative process (such as co-design) to more innovative and deliberative approaches (such as citizens’ juries, also known as mini-publics).

Conventional invited spaces remain an important part of how governments in Australia seek input and advice from the public. For example, written public submissions and public hearings continue to be a primary mode of public input for most formal government and parliamentary inquiries, and responses to environmental impact statements. Similarly elite forms of invited spaces, such as stakeholder committees and external expert advisory bodies, continue to feature prominently in Australia’s policy landscape, even more so in an era of governance where governments increasingly work with non-state actors for their knowledge, networks, resources and legitimacy.[12] Some institutions are slowly adapting the form and function of conventional invited spaces: for example, by supplementing formal hearings with digital inputs, field trips or personal testimonies.[13] Similarly some advisory bodies are expanding beyond giving advice on substantive policy matters by playing a brokering role between government, organised stakeholder groups and the broader community.[14]

Since the early 2000s there has been increased experimentation around Australia with innovative forms of invited spaces that emphasise public deliberation.[15] These spaces encourage participants to engage in informed discussion, critical thinking and reasoned argumentation centred on collective outcomes.[16] Participant numbers in deliberative forms of invited spaces are typically limited, commonly between 15 to 25 people, to enable deep listening and participant interaction. Since deliberative spaces are not open to the broader public, as might be the case in a community meeting, they can exclude some publics from the participatory process. For example, a deliberative process engaging stakeholders might focus on the involvement of organised advocacy groups or peak bodies at the exclusion of everyday members of the public, or a citizens’ jury might involve randomly selected citizens but provide limited opportunities for advocacy groups to participate.[17]

What is a mini-public?

One popular invited space aimed at encouraging deliberation among everyday people is a ‘mini-public’, various forms of which include citizens’ juries, consensus conferences, deliberative polls and citizens’ assemblies. In a mini-public, participants are selected using random selection, with sample stratification to ensure diversity of gender, age and socio-economic background. Depending on the mini-public design, there may be as few as 15 participants or as many as 1,000 plus. Regardless of numbers, the intention is for participants to act as a miniature version of the public, hence the label ‘mini-public’. In a mini-public, participants become informed about the issue under deliberation (through interactive sessions with key experts and interested parties), they engage in facilitated small group deliberation and then typically write a set of recommendations for the decision makers. The entire process can take place over multiple days or sometimes over a period of three to six months.[18] Australia is considered a world leader in the practical uptake up of mini-publics in public policy (see ‘Nuclear Citizens’ Jury’ example).[19]

Who is the ‘public’ in invited spaces?

The relevant ‘public’ for an invited space is typically defined by the nature of the process, its goals and political context.[20] Depending on the purpose of the invited space, individual members of the public, local residents, community groups, advocacy organisations or representatives of stakeholder groups might be targeted or recruited. Invited spaces with an advisory focus typically have people in an ‘expert’ capacity appointed; these might be individuals or representatives of a group with particular knowledge of, or association with, a policy issue.[21]

The term ‘stakeholder’ deserves unpacking because it occurs frequently in participatory policy making. The term originated in the corporate sector, referring to various external parties affected by a company decision.[22] Today the term ‘stakeholder’ commonly refers to any group or individual who has a special interest (‘stake’) or concern in an organisation, proposal or project. Usually (but not always) the term is reserved in public policy for identifiable groups or organisations that have expressed an interest in a particular policy issue or proposal.[23] Stakeholders might also be individuals who have useful knowledge or perspectives, or entities with considerable power, influence and resources to block or promote proposals, such as industry groups and unions.[24]

In public policy many unorganised or informal communities (including everyday citizens) are not labelled as stakeholders because they lack a well-defined, claimed or explicit interest. Instead they are described variously as ‘the broader community’, ‘constituents’, ‘taxpayers’, ‘the silent majority’ or ‘residents’. Typically these more informal, unorganised publics are much harder to identify and invite into a participatory process than organised publics or individuals with a public profile or presence.

Time is another factor that is often constrained in invited spaces. Typically they are instigated by government or a non-state actor for a particular project or process, and operate over a discrete time period. Most commonly invited spaces operate for only a few months, though some go for longer periods – particularly when established to provide advice in the context of high-profile inquiries.[25] The time-bound nature of invited spaces contrasts with the open-ended nature of ‘insisted spaces’ (which we discuss below), where pressure groups and social movements can run campaigns over years or even decades.

Ideally an effective program of invited spaces offers a variety of participatory processes – run either simultaneously or sequentially – to ensure that multiple publics have the opportunity to contribute.[26] This is particularly important for controversial, complex, large-scale or long-term issues, decisions about which have the potential to affect many.[27]

Categorising invited participatory spaces

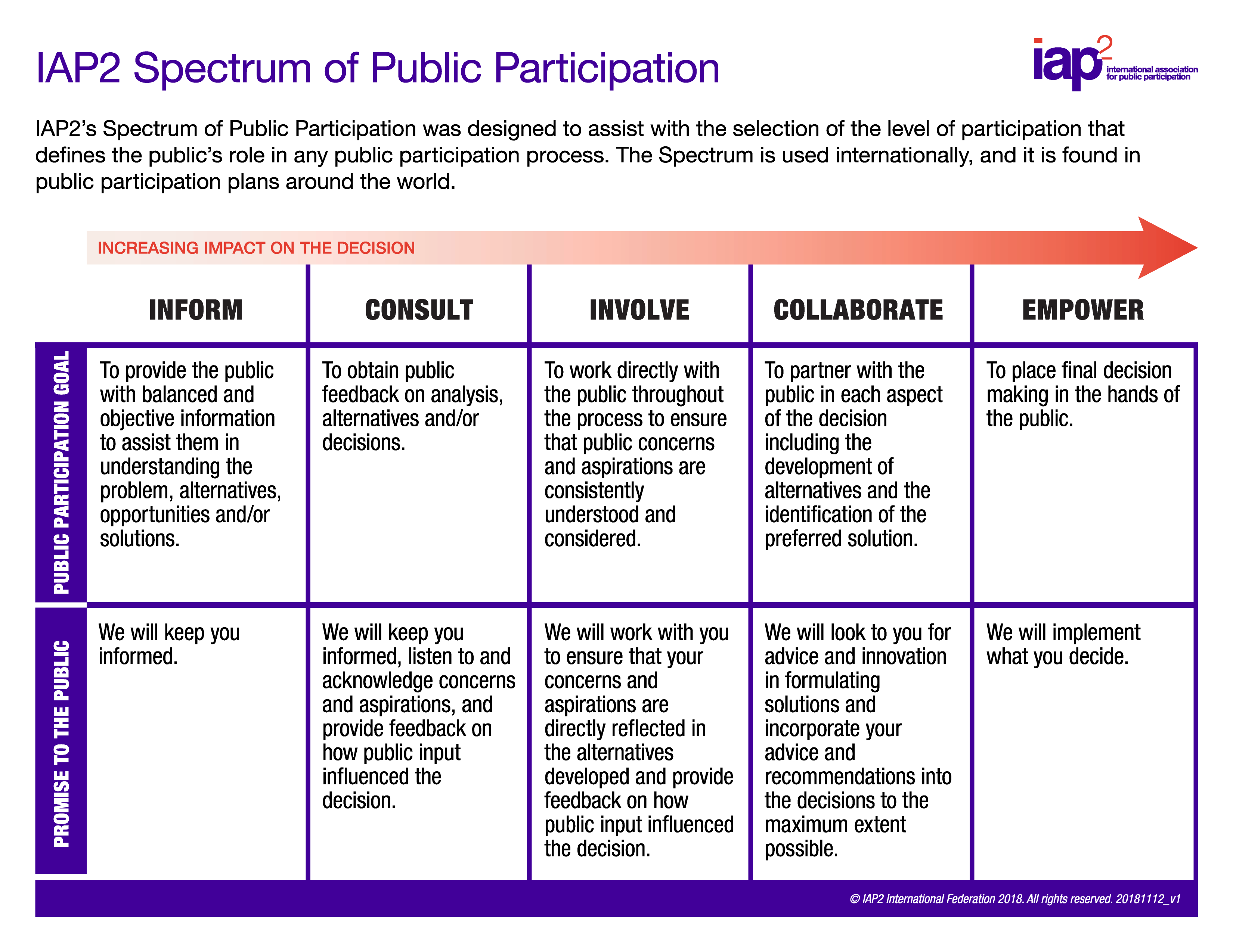

There are many ways to categorise invited spaces. The best-known categorisation distinguishes participation in terms of how much power is handed over to the participants.[28] Consider, for example the frequently cited Public Participation Spectrum of the International Association for Public Participation (IAP2), which differentiates varieties of invited spaces based on their goal and promise to the public, depicted in Figure 1.[29]

Invited spaces at the far right of Figure 1, where the public have full decision-making power, are very rare. While the language of empowerment is common, it is no small thing to devolve decision-making power from decision-making authorities to the public. Doing so confers substantial risk to policy makers, particularly as it may challenge established plans, complicate spending commitments, disrupt longstanding administrative practices and counter political agendas. For example, the South Australian government convened a ‘Nuclear Citizens’ Jury’ process to facilitate public deliberation about the prospects of the state developing a nuclear waste storage facility, and ideally to reach a consensus position.[30] The citizens’ jury recommended against the establishment of a nuclear waste storage facility in the state, yet governments have continued to pursue development. Examples like the Nuclear Citizens’ Jury highlight that participatory processes that are more time-consuming and involved are not necessarily any closer to the ‘empower’ end of the IAP2 spectrum than other ‘lighter-touch’ processes if there is no change to the level of participants’ influence on the outcome.

Invited spaces aimed at collaboration are more common than empowerment. In collaborative arrangements the public is invited to engage in a partnership with government (or an NGO) to work closely over a period of time on a particular problem, project or policy program. In an era of governance, collaborative partnerships have become an important way for governments to access vital knowledge from groups that represent or that provide frontline services to particular publics. At its best, collaboration in public policy can be a generative and creative process, producing outcomes that well exceed the individual inputs. At its worst, collaboration can be used instrumentally by governments (or NGOs) to generate support for predetermined decisions. It is not uncommon for NGOs to be wary of engaging in collaborative exercises led by state or corporate actors; by stepping into the collaborative process they risk losing their independent voice or being ‘co-opted’, and their participation can signal to the broader public that the proposal or decision has their support.

It is not just organised groups that are invited into collaborative policy work. Increasingly individual citizens, in their role as service users, are invited to collaborate with policy designers to improve the delivery and effectiveness of policy programs. Such collaborative processes are often labelled ‘co-design’ – a term that draws on the Scandinavian participatory design tradition where users are involved in the design of workplaces and software systems.[31] Involving end-users collaboratively in the design of policies and programs recognises that the public are ‘experts in their own experiences’.[32] In Australia, co-design ideas have been taken up by a number of state and non-state organisations (especially in the health and welfare sectors) to ensure the complex needs and experiences of users are factored into policy programs.[33] Co-design can also be used to develop structures for ongoing participation or representation (see example on Indigenous Voice). While collaborative processes such as co-design have the potential to be radically participatory, in practice they can struggle to develop into equal partnerships between the state and non-state actors because they challenge dominant ideas within the public service, particularly with respect to what knowledge and expertise is relevant in policy making.[34]

The language in and around invited spaces continues to evolve in Australia. At present the term ‘community engagement’ is used frequently, particularly by professional associations and consultants selling their participatory services to governments, NGOs and private sector organisations. In many cases, ‘community engagement’ refers to a local, geographically bound community rather than a broader public without a specific place-based interest.[35] As the language of participation will undoubtedly continue to evolve, what is most important is attentiveness to the purpose and practice of participatory processes, rather than the label.

Designing invited participatory spaces

The design of invited spaces is a complex craft that involves appraising the existing participatory and political landscape and identifying potentially affected publics and their needs. Design also involves determining the exact remit (or purpose) of the participatory process and matching its goal with suitable participatory methods, and making any necessary procedural modifications. This includes determining how and when to stage the process to meet the diverse needs of the community and decision makers, and juggling these needs with resource, time and governance constraints.

When designing a participatory process in practice, the following questions can be useful to consider (adapted from Hendriks[36]):

- appropriateness: is it necessary, timely and appropriate to engage with the public on the issue at hand?

- purpose: what is the purpose of the project?

- scope: do the participants have a specific remit? Is the agenda open? Where are the topic boundaries and what is out of scope?

- participants: who are the relevant participants? How will they be selected? What roles will they take? Will participants be diverse or will different spaces be created to engage particular kinds of participants?

- outputs: what will the participants produce? What promises can be made to the participants, and what will be done with their recommendations?

- resources: does the project have the necessary finance, time, skills, leadership capacity and other resources?

- connectivity and responsiveness: is the project appropriately connected to relevant institutions? To what extent will the media and the broader public be involved? Does the project have the backing of relevant decision makers and policy actors? How will participants and the broader public be informed about the progress of the implementation?

In recent years there has been considerable experimentation with diverse recruitment methods, such as random selection, to attract less vocal and politically organised people into governance processes (see the mini-public case study). Specific measures can also be taken to minimise the participatory hurdles for ‘hard-to-reach’ publics: for example, by engaging people in places and local venues that they regularly use, offering child care or translation services, making the times and modes of participation more inclusive, and using online engagement to reduce travel demands.

Geography and place more broadly are important factors to consider when designing invited spaces. Some policies may affect publics in particular geographical areas more than others. For example, when designing an invited space for public input on adapting building standards for a changing climate, communities in disaster-prone regions may have particular preferences or needs. Geography also matters in the design of invited spaces seeking public input on locally unwanted land uses (LULUs) such as contested infrastructure proposals or resource extraction projects. In these cases, the local community can be understood as an important and unique stakeholder with special, local and often divided place-based interests. For example, the expansion of coal seam gas into predominantly agricultural areas in Australia has generated significant conflict between locals who welcomed the new industrial activity (often for its employment and economic opportunities), and other locals who opposed it (often due to concerns about environmental and health impacts, quality of life, and encroachment on private property).[37] In such place-based contexts, invited spaces can fuel conflict both between locals, and between locals and non-local interests. For a further example, when the Tasmanian state-owned corporation Hydro Tasmania was designing an invited space to discuss whether or not to develop a large-scale wind energy project on King Island,[38] people with some sort of connection with the island, such as residents or landowners, were prioritised for inclusion. For this project, it would not have made sense to include participants from other parts of Tasmania or coastal Victoria on equal footing with King Islanders, as the decision was far less significant for them than it was for the locals.

Practical guidelines and methods for participatory design abound. These include seminal academic papers, such as Rowe and Frewer’s[39] synthesis of formalised public participation methods (and a framework for evaluating them) and Reed’s[40] review of best-practice stakeholder participation. Other resources include the crowd-sourced website Participedia (participedia.net), which collates participatory techniques, democratic innovations, and cases from around the world. Governments around Australia and international bodies also regularly produce useful frameworks and guidelines on public participation. These include the Australian government’s Australian Public Service Framework for Engagement and Participation[41] and the OECD’s report Innovative Citizen Participation and New Democratic Institutions.[42]

Overall, effective participatory design must be sensitive to context and work with design principles, rather than prescriptive methods or techniques. In efforts to shift the culture of public engagement in the Australian public service from ‘managing stakeholders’ towards ‘engagement of public expertise to deliver better policy programs and services’, the public service has adopted three overarching principles for engagement and participation: to listen; to be genuine; and to be open.[43] What is notable about the principles is the emphasis on the need for public service to ‘be genuine’. This reflects the low trust context within which many invited spaces now operate where the public are wary of engaging in consultation exercises run by governments or corporations that result in little or no action.[44] Communities want to know that the process is genuine and that the decision makers are listening.

The importance of listening

Engagement principles increasingly emphasise the need to actively listen to the public. Most of the effort in designing invited spaces (and indeed in our democratic institutions) focuses on providing opportunities for the public to have voice or on creating an ‘architecture of speaking’.[45] But this has been at the expense of building greater capacity within governments and corporations for listening to the public. The Australian government articulates what listening in engagement ‘looks like’:

- We will think about who the right people to engage are, and the best way to hear what they have to say.

- We will think about when the right time to engage is, for them and for us.

- When seeking opportunities to listen we will be mindful of the conversations that have previously occurred.[46]

Understanding invited spaces in context

Invited spaces are typically designed and convened in dynamic social, political and policy contexts. Effective participatory design is sensitive to how the broader social-political context might shape, and be shaped by, the invited space. And, importantly, how the process may affect the balance of power and outcomes in broader social and political issues. While experiments suggest that a well-designed deliberative process can reduce polarisation and social tension,[47] in practice a highly charged social-political context can make participation and open public debate challenging. For example, when levels of trust in people and institutions are low, the legitimacy of the participatory process can be called into question, and some participants (or even facilitators) may seek to use the process to advance their own agenda. All participatory programs must be attentive to these factors, considering the reciprocal relationship between context and process.

Invited spaces in contested contexts

The future of coal is a controversial topic in Australia, and particularly so in regional coal-producing areas. A prime example is the Hunter Valley in New South Wales, which is the largest regional economy in Australia, with significant contributions from export-oriented mining of thermal coal. Given the risks of climate change, it is therefore not surprising that expansion of coalmining operations in the Hunter Valley is controversial. For this reason, and in response to high-profile instances of corruption among politicians, the New South Wales government established the Planning Assessment Commission (PAC, renamed in 2018 the Independent Planning Commission, IPC) to facilitate community input and provide an independent decision to government on development proposals. The IPC comprises a panel of experts selected by the minister to ‘consult on, and in some circumstances decide the fate of’ significant development proposals.[48] Public participation in the IPC process involves public meetings and written submissions, though no direct influence over the decision outcome. The debate about the future of coal in the region, especially in the broader context of climate change, routinely spills over into the IPC processes, raising tension and stakes in public hearings, heightening conflict between mine supporters and mine opponents.[49]

Invited participatory spaces in the settler-colonial context

In settler-colonial nations like Australia and New Zealand, it is particularly important that invited participatory processes are attentive to the historical and contemporary relationships and power dynamics between First Nations and the state. Indigenous peoples hold a special interest in policy issues, especially those concerning land use and resource management as their interest predates invasion by colonising forces. As explicated by Banerjee[50] in the case of decision making for uranium mining on Mirarr land in northern Australia, the legacy of colonialism and the pre-existing power asymmetry between First Nations people and the settler-colonial government not only shapes the design and outcomes of participatory processes, but the existing power asymmetries can be further exacerbated by inappropriate or instrumental uses of participation.

Meanwhile, ongoing political and epistemic violence to, and dispossession of, Indigenous peoples underpins fundamental power asymmetries between Indigenous communities and those of colonial states and institutions.[51] An important international document that seeks to address these power imbalances by spelling out what constitutes ideal genuine participation for Indigenous peoples in public policy is the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous People (UNDRIP). This document, which was ratified by Australia in 2009, ‘emphasizes the rights of indigenous peoples to live in dignity, to maintain and strengthen their own institutions, cultures and traditions and to pursue their self-determined development, in keeping with their own needs and aspirations’. Articles 3 and 4 of this document define self-determination as the right to ‘freely determine their political status and freely pursue their economic, social and cultural development’ and the ‘right to autonomy or self-government in matters relating to their internal and local affairs, as well as ways and means for financing their autonomous functions’.[52]

Indigenous Voice

A recent example of the ongoing power asymmetry in Indigenous peoples–state relations in Australia is evident in attempts to improve Indigenous peoples’ voice to parliament.[53] In 2016–17 a group of academics and activists at the University of New South Wales led an extensive national consultative process on constitutional recognition of First Nations people in Australia. The consultative process involved thirteen regional dialogues around the country that collectively engaged over 1,200 First Nations people. The decision making of the regional dialogues was then ratified at a National Constitutional Convention in 2017 at Uluru, culminating in a statement (the Uluru Statement from the Heart) calling for a First Nations Voice to Parliament to be enshrined in the Australian Constitution.[54] Advocates argue that the Statement ‘provides a framework for constitutional recognition… [i]ts promise is for meaningful, structural reform to the constitutional hierarchy that will fundamentally change the Indigenous–non-Indigenous relationship’.[55]

Since the development of the Uluru Statement from the Heart, responses from Australian governments have been mixed.[56] The Liberal–National Coalition government that held power at the time the Uluru Statement was developed largely ignored key ideas in the statement, including enshrining an Indigenous Voice in the Constitution.[57] In 2019 the then minister for Indigenous Australians, the Hon. Ken Wyatt AM MP, established a two-staged co-design process to consider different institutional designs for Indigenous Voice. Stage 1 involved a senior advisory group developing ‘proposals for presentation to the Australian Government’, while Stage 2 aimed ‘to consult on the proposals with all Australians to inform a final proposal to the Australian Government’.[58] This co-design was a state-led process that involved extensive consultation including ‘115 community consultation sessions in 67 diverse communities and more than 120 stakeholder meetings around the country’.[59] The process received over 3,000 submissions, 90 per cent of which supported a constitutionally enshrined First Nations Voice.[60] Critics of the government’s co-design process argue that it focused too narrowly on how the Voice might be legislated, rather than incorporated into the Constitution, and thereby failed to consider a fundamental idea in the Uluru Statement. As Appleby et al. explain:

In ignoring the voices of First Nations people in the Uluru Statement and those of the wider Australian public in its own consultation process, the government reinforces the desperate need for a protected, constitutional Voice. Such a Voice, with independent authority and status, could not be ignored in the way that existing government processes and legislated bodies can be.[61]

The trajectory for the settler-colonial state’s response to the Uluru Statement changed following the federal election of May 2022. The new Labor government has committed to ‘implementing the Uluru Statement in full’[62] and proposed ongoing dialogue ahead of a referendum to change the Australian Constitution. Minister for Indigenous Australians Linda Burney has emphasised the importance of listening throughout the forthcoming process of consulting with First Nations leadership and engaging the Australian community broadly.[63]

Spaces where citizens reach in: insisted spaces and citizen-led governance spaces

Although policy makers commonly design invited spaces to enable participation in policy, these spaces sit alongside insisted spaces and citizen-led governance spaces, in which citizens play a much more active role in driving the participation.

Insisted spaces are created when citizens self-organise and mobilise to push an idea or proposal into the policy process. Insisted spaces can sit alongside invited spaces, oftentimes a response to a perceived inadequacy of either the opportunities for input, or the listening capacity of decision makers. Commonly, insisted spaces are forged by social movements, which are ‘networks of informal interactions between a plurality of individuals, groups and/or organizations, engaged in political or cultural conflicts, on the basis of shared collective identities’.[64] Social movements can therefore be a vehicle for citizens to participate in policy, but involvement in a social movement is also a form of participation in itself. Alongside social movements, which are often highly visible in the public sphere, insisted spaces can also be created through the actions of a professionalised advocacy or lobby group. But some of these actors, like lobby groups, will often operate outside the public sphere, for instance via one-on-one meetings with decision makers.[65]

The school strike for climate movement

The school strike for climate movement provides an example of an insisted space that had great influence on the social context in which policy and political debates about climate policy played out. First practised by Swedish teenager Greta Thunberg in 2018 before spreading globally, the school strike movement saw young people mobilising to call for more ambitious and urgent policy action on climate change.[66] The movement, led and driven by young people (who are largely excluded from conventional political participation, such as voting) were protesting to express their concerns about a warming planet. As a result, significant media coverage of the protests increased the issue salience of climate policy in the public sphere. The school strike movement engaged young people around the world, with social media playing an important role in ‘knitting’ together these geographically distributed efforts particularly via the use of hashtags such as #SchoolStrike4Climate[67] and #FridaysForFuture.[68] In this way, a very global social movement (of predominantly young people) had significant impacts on the domestic social context for climate policy debate in many countries.[69]

For policy makers, achieving success in invited spaces requires giving due consideration to the social and political dynamics occurring in insisted spaces too. Changes to social awareness of an issue will often result from the efforts of social movements (for example, in the case of public support for marriage equality[70]) or campaigns in the public sphere by professional advocacy groups (for example, in the case of the mining sector’s opposition to tax reform and climate policy[71]).

‘Citizen-led governance spaces’ are another arena in which citizens initiate their own participation. Departing from insisted spaces, which typically aim to prompt governments to act on policy issues, in citizen-led governance spaces communities themselves take matters into their own hands through a range of practical problem-solving interventions. Such initiatives are also commonly referred to as community-based initiatives, civic enterprises, self-help or mutual aid groups.[72]

Participation in citizen-led governance spaces is not new,[73] but these grassroots efforts have increased in recent years, particularly in OECD countries in response to growing public frustrations over the failure of governments and markets to solve pressing problems like homelessness, food insecurity, renewable energy, affordable housing, substance abuse, domestic violence and rising rates of incarceration.[74]

Community energy

In the context of considerable policy uncertainty on renewable energy, many citizens across Australia have self-organised and pooled their human and financial resources to establish local renewable energy projects. Sometimes these projects involve communities partnering directly with energy retail or distribution companies to assist them in selling and distributing renewable electricity. Communities driving such projects are directly negotiating not only the engineering and financial arrangements with these companies but also the terms of community engagement. For example, the citizens leading Totally Renewable Yackandandah (TRY) in Victoria invited various energy companies to come to interact with the broader public in local community forums. Here, a productive partnership was struck between the citizen-led governance space and a large multinational energy company (AusNet Services).

Citizen-led governance spaces present public policy with both opportunities but also uncertainties. On the one hand, they provide spaces of action where citizens rethink and reframe issues, and generate innovative, experimental and disruptive solutions that may attract the attention of relevant state, market and civil society actors. Yet on the other hand, they can potentially reproduce inequalities, co-opt civil society, behave unaccountably or push the governance of essential public goods onto under-resourced or unrepresentative citizens. A broader worry is that these citizen-led initiatives might simply keep the public busy on reconciling small gaps in the market or state, when they might be better off contesting underlying structural causes of policy problems.[75]

In Australia, the Landcare movement provides an instructive example of the complexities of a citizen-led governance space interfacing with public policy. The Landcare movement emerged in Victoria in the 1970s, the result of a group of landholders seeking to work together to deal with problems with salinity on their properties. Over time the movement spread, leading to governments investing heavily in the Landcare program in order to further enable the successes being achieved.[76] The institutionalisation of Landcare saw governments providing support and funding to enable the citizen-led governance space, but with the consequence of increasing expectations of and administrative burdens on those engaged in the program.[77]

Most recently we have seen communities quickly self-organise local initiatives to provide support and assistance to vulnerable people during the COVID-19 pandemic, the 2019–20 bushfires and the 2022 floods in New South Wales, Queensland and Victoria.[78] Many of these community initiatives demonstrated the informal, relational and embedded ways that communities seek to solve problems, but in some cases these well-intended local efforts disrupted the frontline services of government and formal volunteering organisations. For example, during the Black Summer fires of 2019–20, many communities self-mobilised and created their own informal relief centres, but in some localities these came into tension with formal government recovery centres due to concerns about community safety and the provision of adequate trauma support.[79]

Participatory challenges

For contemporary policy makers the challenges of undertaking public participation abound. For example, they are frequently operating in low trust or polarised contexts, where participation can fuel political cynicism rather than strengthen state–society relations. Increasingly policy makers are trying to engage on highly complex issues (for example, on climate change) where they need to navigate misinformation, competing interests and diverse expectations across multiple layers of government. The context of public participation can also be highly emotional and traumatic, for example, in the wake of a disaster or land-use conflict.[80] Given all these challenges, many government agencies commission independent consultants to design and convene participatory processes. Consultants can inject valuable ‘participatory design’ expertise into the policy-making process, and their involvement can enable governments to be at arm’s length from any public process. But outsourcing the design of invited spaces to external consultants also risks losing important participatory skills from the public sector, and it can potentially limit the involvement and ‘buy in’ of key decision makers to act on public input.[81]

Citizen-led governance spaces can offer innovative arenas for the public to get directly involved in the practical work of tackling collective problems, but they also pose challenges to conventional processes and structures of public policy, and potentially undermine their public legitimacy and broader strategic goals.

Participation also poses risks and challenges to citizens and communities. It demands time, energy and resources, and might produce little or no action from decision makers. Most people participate in a voluntary capacity, and sometimes the effects of participation may take years to result in policy outcomes. An increasing risk is ‘participatory fatigue’ where resource-poor volunteers or communities are continually and regularly being consulted – often with repeat volunteers or representatives involved. From the perspective of community, public participation can be onerous and demanding, whether volunteering in a local protest group or participating in a collaborative process.

There are of course policy issues in contemporary politics for which there is little or no space for public participation. This might be because the issue is deemed too sensitive to open up to public debate, such as national security, or because there simply is not enough public interest. Emerging technologies often fall into this category in which public awareness might be limited, but the public implications of their governance or regulation could be extensive.

Conclusion

In this chapter we have explored some of the key normative, political and practical issues related to different ways the public participates in contemporary public policy. Governments routinely construct invited spaces for public input, though we have argued that participation in contemporary governance extends well beyond formal and structured invited spaces. Participation also takes place in insisted spaces, where citizens or groups might use a protest, social media campaign or consumer boycott to express a view or call for action. Similarly, participation occurs when communities self-organise practical efforts to tackle a particular problem: for example to produce energy or grow food. For our purposes we discussed each of these participatory spaces separately, but of course in practice they all coexist: for example, in parallel or they might overlap in some way. When designing processes for public input in policy, it is important to consider existing participatory spaces and any potential interfaces. Care should be taken to not exclude relevant community groups or voices from an invited space, and the design should not place additional burdens on under-resourced communities.

Future thinking about public participation in public policy needs to expand its focus beyond participatory design, to consider broader systemic questions on how to build democratic capacity within our existing policy processes and institutions. For example, how we can improve deliberation, inclusion and listening in our public institutions, and how might they be more receptive to different kinds of community input? The work ahead here is far less about finding the ‘right’ mechanism for community engagement, and more about supporting and strengthening the capacity of diverse publics to engage constructively in policy issues and collective problem solving more broadly.

References

ABC (2019). Community defenders help fight rainforest bushfires. 7.30 Report. Australian Broadcasting Corporation, 5 November. https://www.abc.net.au/7.30/community-defenders-help-fight-rainforest-bushfires/11782166

Alexander, N., T. Petray and A. McDowall (2022). More learning, less activism: narratives of childhood in Australian media representations of the school strike for climate. Australian Journal of Environmental Education 38(1): 1–16.

Allam, L. (2022). ‘It’s not wise to be rushed’: Linda Burney says government will consult extensively on Indigenous voice. Guardian, 31 July. https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2022/jul/31/its-not-wise-to-be-rushed-linda-burney-says-government-will-consult-extensively-on-indigenous-voice

Althaus, C., P. Bridgman and G. Davis (2018). The Australian policy handbook: a practical guide to the policy-making process. London: Routledge.

Appleby, G., E. Buxton-Namisnyk and D. Larkin (2021). Half-measures won’t do on the Voice, minister: Australians have spoken. Sydney Morning Herald, 7 July. https://www.smh.com.au/national/half-measures-won-t-do-on-the-voice-minister-australians-have-spoken-20210707-p587on.html

Appleby, G. and E. Synot (2020). A First Nations Voice: institutionalising political listening. Federal Law Review 48(4): 529–42.

Arnstein, S.R. (1969). A ladder of citizen participation. Journal of the American Institute of Planners 35(4): 216–24.

Australian Labor Party (2022). Fulfilling the Promise of Uluru. Australian Labor Party. https://www.alp.org.au/policies/fulfilling-the-promise-of-uluru.

Banerjee, S. B. (2000). Whose land is it anyway? National interest, Indigenous stakeholders, and colonial discourses: the case of the Jabiluka uranium mine. Organization and Environment 13(1): 3–38.

Barnes, M., J. Newman, A. Knops and H. Sullivan (2003). Constituting ‘the public’ in public participation. Public Administration 81(2): 379–99.

Bherer, L., M. Gauthier and L. Simard, eds (2017). The professionalization of public participation. New York: Routledge.

Bingham, L.B., T. Nabatchi and R. O’Leary (2005). The new governance: practices and processes for stakeholder and citizen participation in the work of government. Public Administration Review 65(5): 547–58.

Blomkamp, E. (2018). The promise of co‐design for public policy. Australian Journal of Public Administration 77(4): 729–43.

Bobbio, L. (2019). Designing effective public participation. Policy and Society 38(1): 41–57.

Boulianne, S., M. Lalancette and D. Ilkiw (2020). ‘School strike 4 climate’: social media and the international youth protest on climate change. Media and Communication 8(2): 208–18.

Brickell, C. and J. Bennett (2021). Marriage equality in Australia and New Zealand: a trans‐Tasman politics of difference. Australian Journal of Politics and History 67(2): 276–94.

Cabinet Office (2017). Open policy making toolkit. GOV.UK. https://www.gov.uk/guidance/open-policy-making-toolkit

Calyx, C. and B. Jessup (2019). Nuclear citizens jury: from local deliberations to transboundary and transgenerational legal dilemmas. Environmental Communication 13(4): 491–504.

Cameron, S. and I. McAllister (2019). Trends in Australian political opinion: results from the Australian Election Study 1987–2019. Canberra: Australian National University.

Chilvers, J., H. Pallett and T. Hargreaves (2018). Ecologies of participation in socio-technical change: the case of energy system transitions. Energy Research and Social Science 42: 199–210.

Colvin, R.M. and E. Przybyszewski (2022). Local residents’ policy preferences in an energy contested region – The Upper Hunter, Australia. Energy Policy 162: 112776.

Colvin, R.M., G.B. Witt and J. Lacey (2016a). Approaches to identifying stakeholders in environmental management: insights from practitioners to go beyond the ‘usual suspects’. Land Use Policy 52: 266–76.

—— (2016b). How wind became a four-letter word: lessons for community engagement from a wind energy conflict in King Island, Australia. Energy Policy 98: 483–94.

Commonwealth of Australia (2020a). The Australian Public Service Framework for Engagement and Participation. Canberra. https://www.industry.gov.au/data-and-publications/aps-framework-for-engagement-and-participation

—— (2020b) Royal Commission into national disaster arrangements report. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia.

—— and National Indigenous Australians Agency (2020). Indigenous Voice Co-design Process: Interim Report to the Australian Government. Commonwealth of Australia. https://voice.niaa.gov.au/sites/default/files/2021-02/indigenous-voice-codesign-process-interim-report-2020.pdf.

—— and National Indigenous Australians Agency (2021). Indigenous Voice Co-Design Process: Final Report to the Australian Government Commonwealth of Australia. https://voice.niaa.gov.au/sites/default/files/2021-12/indigenous-voice-co-design-process-final-report_1.pdf.

Crowe, D. (2021). ‘Stringing people along’: new fears Coalition cannot deliver on Voice. Sydney Morning Herald, 7 July. https://www.smh.com.au/politics/federal/stringing-people-along-new-fears-coalition-cannot-deliver-on-voice-20210706-p587e6.html

Crowley, K. and B.W. Head (2017). Expert advisory councils in the policy system. In M. Brans, I. Geva-May and M. Howlett, eds. Routledge handbook of comparative policy analysis, 181–97. London: Routledge.

Crowley, K., J. Stewart, A. Kay and B.W. Head (2020). Reconsidering policy: Complexity, governance and the state. Bristol, UK: Policy Press.

Della Bosca, H. and J. Gillespie (2019). The construction of ‘local’ interest in New South Wales environmental planning processes. Australian Geographer 50(1): 49–68.

Dewey, J. (1927). The public and its problems. Oxford, UK: Holt.

Diani, M. (1992). The concept of social movement. Sociological Review 40(1): 1–25.

Edelenbos, J., A. Molenveld and I. van Meerkerk (2020). Civic engagement, community-based initiatives and governance capacity: an international perspective. New York: Routledge.

Ercan, S.A., C.M. Hendriks and J.S. Dryzek (2019). Public deliberation in an era of communicative plenty. Policy and Politics 47(1): 19–36.

Evans, M. and N. Terrey (2016). Co-design with citizens and stakeholders. In G. Stokerand and M. Evans, eds. Evidence-based policy making in the social sciences: methods that matter, 243–62. Bristol, UK: Policy Press.

Everingham, J.-A., V. Devenin and N. Collins (2015). ‘The beast doesn’t stop’: the resource boom and changes in the social space of the Darling Downs. Rural Society 24(1): 42–64.

Fishkin, J., A. Siu, L. Diamond and N. Bradburn (2021). Is deliberation an antidote to extreme partisan polarization? Reflections on ‘America in One Room’. American Political Science Review: 1–18.

Glicken, J. (2000). Getting stakeholder participation ‘right’: a discussion of participatory processes and possible pitfalls. Environmental Science and Policy 3(6): 305–10.

Harding, R., C.M. Hendriks and M. Faruqi (2009). Environmental decision making: exploring complexity and context. Sydney: Federation Press.

Haughton, G. and P. McManus (2019). Participation in postpolitical times. Journal of the American Planning Association 85(3): 321–34.

Head, B.W. (2007). Community engagement: participation on whose terms? Australian Journal of Political Science 42(3): 441–54.

Hendriks, C.M. (2012). Participatory and collaborative governance. In R. Smith, A. Vromen and I. Cook, eds. Contemporary politics in Australia: theories, practices, and issues, 188–198. Melbourne: Cambridge University Press.

—— (2020). Advocates: interest groups, civil society organisations and democratic innovation. In O. Escobar and S. Elstub, eds. International handbook of democratic innovation and governance, 241–54. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar Press.

—— (2021). Studying Australian politics through the lens of deliberative democracy: participation, deliberation and inclusion. In J. M. Lewis and A. Tiernan eds. Oxford Handbook of Australian Politics. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

—— and A.W. Dzur (2022). Citizens’ governance spaces: democratic action through disruptive collective problem-solving. Political Studies 70(3), 680–700

Hendriks, C.M., S. Regan and A. Kay (2019). Participatory adaptation in contemporary parliamentary committees in Australia. Parliamentary Affairs 72(2): 267–89.

Herrmann, C., S. Rhein and I. Dorsch (2022). #fridaysforfuture – shat does Instagram tell us about a social movement? Journal of Information Science. DOI: 10.1177/01655515211063620.

International Association for Public Participation (2014). IAP2’s Public Participation Spectrum. IAP2. https://cdn.ymaws.com/www.iap2.org/resource/resmgr/pillars/Spectrum_8.5x11_Print.pdf.

Kimbell, L. (2015). Applying design approaches to policy making: discovering policy lab. Brighton, UK: University of Brighton.

Lockie, S. (2004). Collective agency, non-human causality and environmental social movements. Journal of Sociology 40(1): 41–57.

Macnamara, J. (2017). Creating a ‘democracy for everyone’ – strategies for increasing listening and engagement by government. The London School of Economics and Political Science and University of Technology Sydney. https://www.lse.ac.uk/media-and-communications/assets/documents/research/2017/MacnamaraReport2017.pdf

McKnight, D. and M. Hobbs (2013). Public contest through the popular media: the mining industry’s advertising war against the Australian Labor government. Australian Journal of Political Science 48(3): 307–19.

Mitchell, R.K., B.R. Agle and D.J. Wood (1997). Toward a theory of stakeholder identification and salience: defining the principle of who and what really counts. Academy of Management Review 22: 853–86.

Nabatchi, T. and M. Leighninger (2015). Public participation for 21st century democracy. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (2020). Innovative citizen participation and new democratic institutions. https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/content/publication/339306da-en

Ostrom, E. (1990). Governing the commons: the evolution of institutions for collective action. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Papadopoulos, Y. (2013). Democracy in crisis? Politics, governance and policy Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

Parry, L., J. Alver and N. Thompson (2019). Democratic innovation in Australasia. In S. Elstub and O. Escobar, eds. Handbook of democratic innovation and governance, 435–48. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar Publishing.

Ransan-Cooper, H., S.A. Ercan and S. Duus (2018). When anger meets joy: how emotions mobilise and sustain the anti-coal seam gas movement in regional Australia. Social Movement Studies 17(6): 635–57.

Reed, M. (2008). Stakeholder participation for environmental management: a literature review. Biological Conservation 141: 2417–31.

Rhodes, R.A.W. (2007). Understanding governance: ten years on. Organization Studies 28(8): 1243–64.

Rowe, G. and L.J. Frewer (2000). Public participation methods: a framework for evaluation. Science, Technology and Human Values 25(1): 3–29.

Royal, T. (2021). Private land conservation policy in Australia: minimising social–ecological trade-offs raised by market-based policy instruments. Land Use Policy: DOI: 10.1016/j.landusepol.2021.105473.

Setälä, M. and G. Smith (2018). Mini-publics and deliberative democracy. The Oxford handbook of deliberative democracy, 300–14. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

The Uluru Statement (2022). http://www.ulurustatement.org

United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (2013). United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, HR/PUB/13/2. United Nations. https://www.un.org/development/desa/indigenouspeoples/wp-content/uploads/sites/19/2018/11/UNDRIP_E_web.pdf

Wesselink, A., J. Paavola, O. Fritsch and O. Renn (2011). Rationales for public participation in environmental policy and governance: practitioners’ perspectives. Environment and planning A: economy and space 43(11): 2688–704.

Wilson, S., D. Sivasubramaniam, J. Farmer, A. Aryani, T. De Cotta, P. Kamstra, V. Adler and J. Knox (2020). Everyday humanitarianism during the 2019/2020 Australian bushfire crisis, Melbourne: Swinburne Social Innovation Research Institute and Australian Red Cross.

About the authors

Carolyn M. Hendriks is a Professor at the Crawford School of Public Policy at the Australian National University. She undertakes engaged interpretive social research that brings democratic practice into dialogue with political theory. Carolyn teaches and has published widely on democratic aspects of contemporary governance, including public participation, deliberation, inclusion, listening and representation. Carolyn’s current research is exploring how citizens themselves are leading collective problem-solving efforts to address governance voids or to repair democratic institutions. Carolyn is the author of three books, including Mending Democracy (with Ercan & Boswell, Oxford University Press, 2020), The Politics of Public Deliberation (Palgrave, 2011) and Environmental Decision Making: exploring complexity and context (with Harding & Faruqi, Federation Press 2009).

Rebecca M. Colvin is a social scientist and senior lecturer at the Crawford School of Public Policy at the Australian National University. Rebecca researches the social and political dimensions of contentious issues associated with climate policy and energy transition. Her research is focused on understanding the complexity of how different people and groups engage with social, policy, and political conflict about climate and energy issues, particularly through the theoretical lens of the social identity approach. She has explored conflict about wind energy, coal seam gas, coal, and climate policy and energy transition more broadly, in settings ranging from the public sphere through to local communities.

- Hendriks, Carolyn M. and Rebecca M. Colvin (2024). Spaces of public participation in contemporary governance. In Nicholas Barry, Alan Fenna, Zareh Ghazarian, Yvonne Haigh and Diana Perche, eds. Australian politics and policy: 2024. Sydney: Sydney University Press. DOI: 10.30722/sup.9781743329542. ↵

- Dewey 1927. ↵

- Ercan, Hendriks and Dryzek 2019. ↵

- Head 2007. ↵

- Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) 2020. ↵

- Parts of this text draw from Harding, Hendriks and Faruqi 2009. ↵

- Rhodes 2007. ↵

- Papadopoulos 2013; Crowely et al. 2020. ↵

- Cf. Althaus, Bridgman and Davis 2018, chapter 7. ↵

- Wesselink et al. 2011. ↵

- Haughton and McManus 2019, 332. ↵

- Crowely et al. 2020. ↵

- Hendriks, Regan and Kay 2019. ↵

- Crowley and Head 2017. ↵

- Parry, Alver and Thompson 2019. ↵

- Nabatchi and Leighninger 2015. ↵

- Hendriks 2020. ↵

- Setälä and Smith 2018. ↵

- For an overview of some practical examples on mini-publics in Australia, see Parry, Alver and Thompson 2019. For an overview of the history and evolution of deliberative democracy in Australia, see Hendriks 2021, 472–90. ↵

- Barnes et al. 2003. ↵

- Crowley et al. 2020, 100–3. ↵

- Mitchell, Agle and Wood 1997. ↵

- Colvin, Witt and Lacey 2016a. ↵

- See Mitchell, Agle and Wood 1997; Glicken 2000; Bingham, Nabatchi and O’Leary 2005. ↵

- Crowley et al. 2020. ↵

- Nabatchi and Leighninger 2015; Bobbio 2019. ↵

- Chilvers, Pallett and Hargreaves 2018. ↵

- Arnstein 1969. ↵

- International Association for Public Participation 2014. ↵

- Calyx and Jessup 2019. ↵

- Kimbell 2015. ↵

- Cabinet Office 2017. ↵

- See Blomkamp 2018. ↵

- Evans and Terrey 2016. ↵

- Colvin, Witt and Lacey 2016a. ↵

- Hendriks 2012. ↵

- Everingham, Devenin and Collins 2015. ↵

- Colvin, Witt and Lacey 2016b. ↵

- Rowe and Frewer 2000. ↵

- Reed 2008. ↵

- Commonwealth of Australia 2020a. ↵

- OECD 2020. ↵

- Commonwealth of Australia 2020a. ↵

- The Australian Election Study, which has been running since 1987, has found that trust in government has declined rapidly in recent years; in 2019 only one in four Australians surveyed believed that people in government could be trusted: Cameron and McAllister 2019, 99. ↵

- Macnamara 2017. ↵

- Commonwealth of Australia 2020a. ↵

- Fishkin et al. 2021. ↵

- Della Bosca and Gillespie 2019, 51. ↵

- Colvin and Przybyszewski 2022. ↵

- Banerjee 2000. ↵

- See chapter on ‘Indigenous politics’ by Perche and O’Neil in this volume. ↵

- United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) 2013. ↵

- This process is also discussed in more detail in Perche and O’Neil’s chapter (in this volume), ‘Indigenous Politics’. ↵

- For details on the history and goals of the Uluru Statement, see The Uluru Statement 2022. ↵

- Appleby and Synot 2020, 542. ↵

- At the time of writing in August 2022. ↵

- Crowe 2021. ↵

- Commonwealth of Australia and National Indigenous Australians Agency 2020. ↵

- Commonwealth of Australia and National Indigenous Australians Agency 2021. ↵

- Appleby, Buxton-Namisnyk and Larkin 2021. ↵

- Appleby, Buxton-Namisnyk and Larkin 2021. ↵

- Australian Labor Party 2022. ↵

- Allam 2022. ↵

- Diani 1992, 13. ↵

- See Byrne’s chapter on ‘Pressure groups’ in this volume. ↵

- Alexander, Petray and McDowall 2022. ↵

- Boulianne, Lalancette and Ilkiw 2020. ↵

- Herrmann, Rhein and Dorsch 2022. ↵

- See Collin and McCormick’s chapter ‘Young People and Politics’ in this volume. ↵

- See Brickell and Bennett 2021. ↵

- See McKnight and Hobbs 2013. ↵

- Hendriks and Dzur 2022. ↵

- Ostrom 1990. ↵

- Edelenbos, Molenveld and van Meerkerk 2020. ↵

- Hendriks and Dzur 2022. ↵

- Royal 2021. ↵

- Lockie 2004. ↵

- ABC 2019; Wilson et al. 2020. ↵

- Commonwealth of Australia 2020b, 465. ↵

- Ransan-Cooper, Ercan and Duus 2018. ↵

- Bherer, Gauthier and Simard 2017. ↵