16 South Australia

Josh Holloway; Mark Dean; and Rob Manwaring

Key terms/names

Australian Labor Party, bicameralism, Cabinet, Constitution Act 1934 (SA), deliberative democracy, Don Dunstan, Liberal Party of South Australia, malapportionment, marginal seats, political parties, privatisation, Thomas Playford

South Australia is something of a paradox within Australia’s federation.[1] On the one hand, with a population of 1.77 million, it often remains peripheral. In 2018, due to lack of population growth in proportion to the rest of the country, it had its overall number of federal MPs in the House of Representatives reduced from 11 to 10, thus further diminishing its voice on the national stage. Federal elections tend not to be decided by outcomes in South Australia. Economically, South Australia has been perceived to be a ‘rust-bucket’ state — economically backward with a critical skills shortage, and an ageing population. According to the Australian Bureau of Statistics, it makes up just over 6 per cent of the nation’s economy. In 1991, the collapse of the State Bank was a significant blow to the state’s economy. It has often taken South Australia longer to recover from national economic downturns and usually ranks just above Tasmania in many economic metrics. More recently, with the closure of the Holden car plant in 2017 — and the effective end of car manufacturing in Australia — there remain ongoing concerns about the future and vitality of the state. There is a lingering perception that South Australia is, to quote a former Premier of Victoria, a ‘backwater’.

Yet, these perceptions tend to mask a more complex and rich political history. While South Australia faces economic challenges, politically, the state has often led the nation in innovations and democratic practice. South Australia has a stable political system: aside from the State Bank collapse, it has been free of the scandals and corruption that have blighted other states and territories like New South Wales and Western Australia at one time or another. Its political system and workings can appear, at first glance, quite mundane. However, South Australia has a unique and radical history. It was established as a planned ‘free settlement’ on terms quite different from the other Australian colonies. It was, and continues to be for some, a ‘social laboratory’ with a rich history of political and social innovation;[2] and it has pioneered legislation and political innovations, particularly throughout the 1970s.[3] While South Australian politics, like the rest of the nation, has been dominated by the Labor/non-Labor axis, it has been the birthplace of a range of political movements and parties including the Australian Democrats; the Family First party; and most recently the Nick Xenophon-led ‘Centre Alliance’. While an Australian prime minister has never represented a South Australian constituency, the state continues to influence and shape Australian political debates, especially most recently in the areas of water and energy policy. In 2018, Adelaide became the home of the new Australian Space Agency – perhaps reflecting a state that can often ‘punch above its weight’ in the federation.

South Australia’s System of Government

The Constitution Act 1934 is the foundation of South Australia’s political system, setting out the main framework and its core constitutional features.[4] As with the other states, SA has a parliamentary system of government with strong Westminster characteristics, clearly influenced by the colonial imprint of the UK. In 1856, South Australia became a self-governing colony, and the original 1856 Constitution was, for its time, one of the most progressive in the world, with a range of radical features including the scope of its franchise and innovations such as the secret ballot.[5] As again with the other states, at the core of the SA system of government is the convention of responsible government whereby the political executive holds office insofar as it has the confidence of the lower house of parliament and is accountable to the people via their elected representatives in parliament. This is the model of how political accountability should work in South Australia, but as we highlight below, there are ongoing questions with how well it actually works.

South Australia has a strongly bicameral legislature comprising the lower house (the House of Assembly) and an upper house (the Legislative Council). Government is formed by the group winning a majority of seats in the lower house and the leader of the winning party becomes Premier. Since 1970, the House of Assembly has 47 members, and 24 votes are required to gain a majority. It is worth noting that the South Australian House of Assembly is relatively small (e.g. the WA Parliament has 95 members with a population of 2.6m), and this has had an impact on government formation. The Legislative Council has 22 members (MLCs), each serving eight-year terms, with half the upper house facing election on alternating cycles.

In the event of a deadlock between the two houses, section 41 of the Constitution Act provides for the government to seek permission to dissolve the parliament and hold new elections, although this power has never been used.[6] The main mechanism to resolve deadlocks has been the use of Conference Procedures to broker agreement on disputed bills.[7] There have been calls to abolish the upper house, and in 2015 then Labor Premier Mike Rann backed away from holding a referendum on the issue.[8] There appears, however, to be limited appetite for a unicameral system, such as in Queensland.

South Australia operates a majoritarian, full preferential, single member electoral system for the House of Assembly, and a proportional representative system for the upper house, with the single transferable vote. Lower House members serve four-year terms, and Members of the Legislative Council (MLCs) serve for eight years. There has been sporadic media and political commentary arguing for reform by reducing the term length for MLCs.[9]

South Australian Distinctiveness

While similar to other states, the South Australian political system has some distinct features, not least the issue of boundaries and boundary redistribution. South Australia has had a long history of malapportionment or what was termed the ‘Playmander’ — with highly disproportionate electorate sizes[10] giving disproportionate representation to rural constituencies, violating the principle of ‘one vote, one value’. The term was rather maladroit, since malapportionment is rather different from ‘gerrymandering’, the manipulation of individual electoral boundaries for partisan advantage. While malapportionment was abolished in the 1970s, the issue of electoral boundaries remains contentious in South Australian politics for several reasons. First, South Australia has a distinct geography. After Western Australia, South Australia has the second-most highly concentrated population, with most people living in or near Adelaide or the other major urban centres (approximately 75 per cent of a total state population of 1.67 million). This means that most elections are decided by marginal seats in metropolitan or outer suburban areas.

Second, and relatedly, there tends to be a rough distinction between where the voters and supporters of the major parties reside. An issue for the Liberal Party, especially during the Rann–Weatherill years, was that its voters live disproportionately in rural areas. The effect is that their vote tends to be concentrated, and, despite winning the popular vote, they have often lost the contest for winning most seats. The Liberals ‘won’ the two-party preferred vote at the 2002, 2010 and 2014 elections but did not win office.

Third, and what was unique to South Australia, one reason electoral boundaries proved to be so problematic was the so-called fairness provision in the Constitution Act, overseen by SA’s Electoral Division Boundaries Commission. This clause was introduced by Labor in 1991 and was supported by the Liberals. It required that after each election the electoral boundaries be redrawn to ensure that the winning party or grouping that secured 50 per cent of the two-party preferred vote should be able to be ‘elected in sufficient numbers to enable a government to be formed’.[11] Pursuit of this form of electoral ‘fairness’ proved elusive, however, and from 1997 to 2018, only three of the six winning governments achieved over 50 per cent of the two-party preferred count. In one of the final acts of the 2014–18 parliament, the Greens introduced a Bill to remove the ‘fairness provision’ from the Constitution Act, and with the support of Labor and others the Bill was passed in December 2017.[12]

The political history of South Australia

Political stability is one of the defining features of South Australian political history in the 20th and early 21st centuries. By as early as 1905, a Labor versus non-Labor two-party contest came to dominate the state’s politics, mirroring the emerging dynamics at the national level. Since the 1930s, South Australian voters have also been prepared to return incumbent governments at successive elections, creating a series of distinct eras of political leadership — several of which we explore below. What these periods of alternating long-term Liberal and Labor government hide, however, are considerable shifts in voting patterns and the significant influence of electoral systems. Further, focusing on the Labor versus Liberal contest alone obscures the enduring impact of independent members of parliament, the presence of which has contributed to several minority governments. More recently, as well, minor parties have expanded their influence in the Legislative Council — the powerful upper house of parliament.[13]

The Playford era (1938–65)

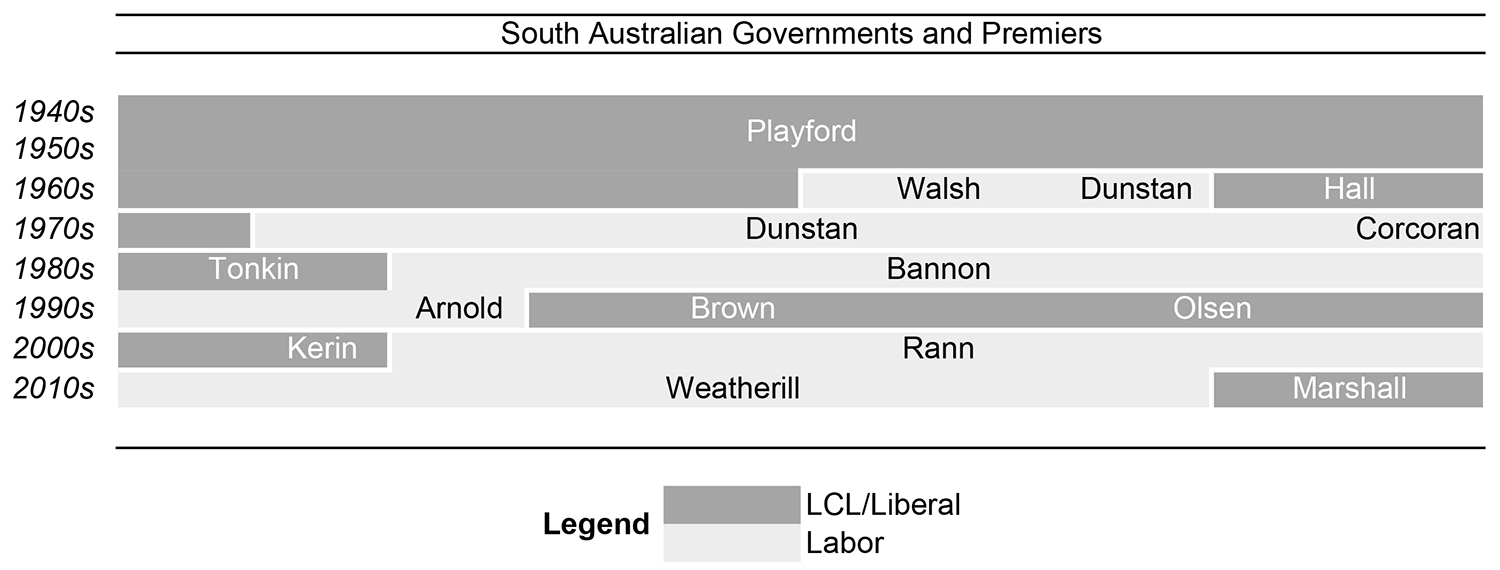

As Figure 1 displays, South Australia began the postwar period during the Playford era. Sir Thomas Playford was the longest-serving premier in Australian history, leading the Liberal Country League (LCL) government from 1938 to 1965 and steering his party through eight election wins. The Playford era is most notable for its ‘forced industrialisation’ of the South Australian economy. The Playford governments frequently intervened in markets, established publicly owned utilities and housing, and led a transformation of the state’s economy away from a largely rural-agricultural base to a more significant industrial base. Public spending on health and education was often lower, though, than in other states, while the paternalism and conservatism of Playford’s LCL meant that South Australia also significantly lagged behind in social and cultural policy reform.

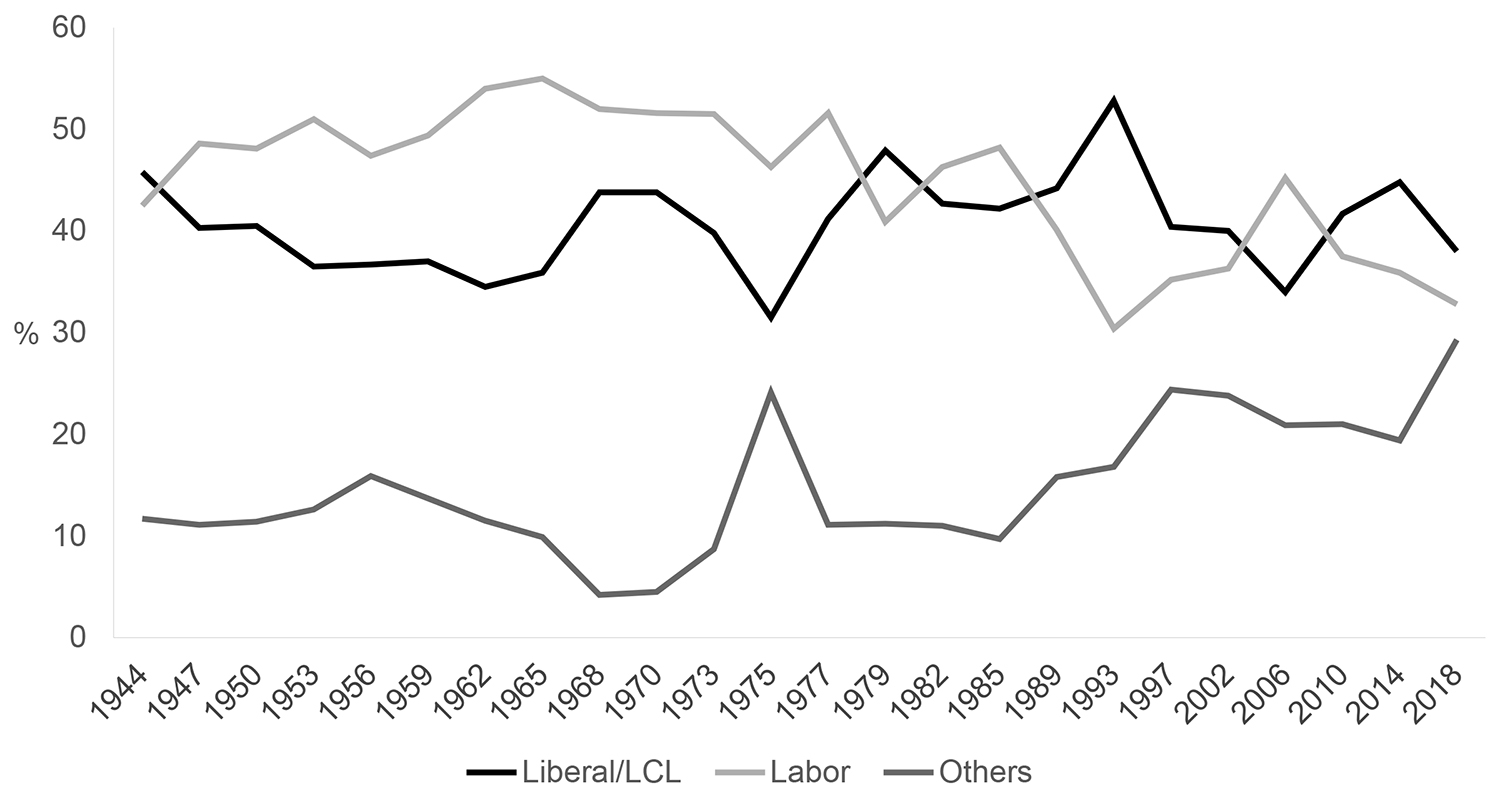

Industrial expansion and economic growth underpinned both the LCL’s and Playford’s personal electoral popularity. But they also contributed to Playford’s eventual demise, as economic transformation fostered a changed political geography, with population moving from rural areas and concentrating in the metropolitan region. Indeed, if not for the peculiarities of South Australia’s electoral system (outlines above) at the time, the Playford era likely would have been much shorter.[14] Figure 2 shows the share of the first preference votes of the LCL/Liberal and Labor in House of Assembly elections from 1944 to 2018. For much of the Playford era, the Labor Party secured more popular support. Indeed, in 1944, 1953 and 1962 this led to the Labor Party winning the estimated two-party preferred vote but nonetheless losing the election. This was a product of the severe electoral malapportionment explored above. It was not until the 1970s that South Australia had a genuinely democratic electoral system founded upon a ‘one vote, one value’ principle and a level playing field for parties.

The Dunstan decade (1970–79)

Though not the first Labor government of the postwar era, the Dunstan decade of 1970–79 nevertheless is the clearest break with the long dominance of the LCL through the mid-20th century. Don Dunstan’s governments were a highly activist brand of social democracy, and a new type of Labor government: ‘electorally successful, effectively reformist, and unashamedly appealing to middle-class voters’.[15] Dunstan brought about a ‘technocratic’ shift for Labor, elevating the role of technical expertise and evidence in policy making, but later also increased public participation in some aspects of decision making. The social reforms (e.g. Aboriginal land rights, decriminalisation of homosexuality, first female judge appointed) and expansions to individual liberty (e.g. easing censorship, reforming liquor licensing, establishing a nude beach) were, in many cases, nationally significant, and in some cases world firsts.[16] The Dunstan government, however, occasionally struggled with the challenges of economic management, albeit in the context of a narrow economic base in the state and worsening global economic conditions.

The Bannon decade (1982–92)

As Figures 1 and 2 show, the Labor Party quickly recovered from the loss of government in 1979, returning to power just three years later. But Premier John Bannon was a Labor leader substantially different from Dunstan. Where Dunstan was charismatic, ostentatious and a zealous reformer, Bannon was cautious, mainstream, and sought incremental change. Where social and cultural transformations were the aim of Dunstan’s Cabinets, Bannon’s governments focused more on careful economic management.[17] Under Bannon, Labor enjoyed considerable successes, seeing the opening of the Olympic Dam mining project, expansion of the defence industry, development of the public transportation system, greater environmental protection, and reforms in the school and criminal justice systems. But the collapse of the government-owned State Bank, one of the largest economic crises in South Australia’s history, brought about the end of Bannon’s premiership and, soon after, a decade in opposition for the Labor Party. Interpretations differ on Bannon’s record in office:[18] critics see a decade of missed opportunities (especially in contrast to Dunstan’s record), while others laud modest reform in much more economically constrained times.

The Brown/Olsen/Kerin governments (1993–2002)

The Brown–Olsen–Kerin era was the sole period of sustained Liberal Party government since Playford (the Tonkin Liberal government of 1979–82 lasting just a single parliamentary term). In 1993 Dean Brown led the Liberal Party to a landslide victory in an election that saw the peak of the Liberal Party’s electoral support in the postwar period (see Figure 1). The Brown government, however, was beset by factional infighting, slowing the pace of policy reform. This infighting was a continuation of party leadership rivalries between Dean Brown and John Olsen, who represented, respectively, the moderate and conservative groupings within the SA Liberals.[19] By 1996, opinion poll figures of Liberal and Labor support had narrowed, prompting two Liberal backbenchers to shift their support for party leadership from Brown to Olsen, allowing Olsen to make a successful challenge for party leadership.

Under Olsen’s leadership, the Liberals narrowly won the 1997 election, forming minority government with the support of independents. The Olsen government successfully broadened South Australia’s economic base, initiated major sporting events (e.g., the Tour Down Under), and further developed the tourism industry. The Olsen government was also marked by several policy controversies, notably the privatisation of electricity assets (Electricity Trust of South Australia, ETSA) and the mass outsourcing of government services. The privatisation of ETSA caused increases in the price of electricity, reducing further Olsen’s electoral popularity. Ultimately, however, the ‘Motorola affair’ (Olsen’s attempt to lure the technology company to the state with subsidies and preferential treatment) and Olsen’s subsequent misleading of parliament led to his downfall, being replaced as party leader and (until the 2002 election) premier by Rob Kerin.

The Rann/Weatherill era (2002–18)

Mike Rann emerged as leader of the Labor Party following its election loss in 1993, where Labor’s primary vote was reduced to just 30.4 per cent (see Figure 1). Rann benefitted from a Liberal Party in disarray, and after just two terms in opposition, led Labor to victory in 2002, forming a minority government. Through much of the Rann era, South Australia experienced sustained economic expansion and relatively low unemployment, helping Labor rebuild its economic credibility after the crises of the later Bannon years. Substantial inequality and economic disadvantage remained, however, and Rann often clashed with local trade unions. Nonetheless, the Rann era was one of considerable achievements, including increased funding for health and education; the growth of the mining and defence industries; considerable infrastructure and tourism site development; and innovations in participatory democracy and governance.[20] Some view the Rann era as a variant of the emerging ‘third way’ politics in the renewal of social democracy.[21]

As popular opinion began to shift against Rann, leading union and Labor Party figures moved to replace him. Public fatigue with a third-term government, coupled with the effects of the Global Financial Crisis placed greater constraints on Rann’s government. Knowing he lacked the numbers to withstand any leadership challenge, Rann stood down in October 2011, with Jay Weatherill elected unopposed by the party as his successor. Weatherill faced considerable economic challenges in his first term, including the closing of prominent manufacturing sites and aborted plans for mining projects. Early budgets made large cuts to spending and privatised public assets and services. Yet, following a surprise win in the 2014 election, Labor’s agenda under Weatherill substantively changed. Weatherill led significant social reform (e.g., removing discriminatory laws against the LGBTIQ community), and demonstrated a capacity for policy innovation in economic management. Perhaps most notable is Weatherill’s proposed reform of the electricity sector, arguing for the construction of a government-owned gas-fired power station alongside the expansion of renewable energy and grid-connected battery storage.

From Marshall to Malinauskas (2018–2023)

After a long period of Labor rule, the Liberals returned to power in South Australia in 2018, led by Steven Marshall. However, this resurgence proved to be short-lived. The Liberals under Marshall became a one-term government after a somewhat unexpected loss to Labor, led by Peter Malinauskas, in the 2022 state election. The Marshall Liberal government was generally competent, headed by a leader and deputy leader (Vicky Chapman) from the party’s moderate wing. Marshall’s government enacted some notable policy changes, including the introduction of voluntary assisted dying legislation and the decriminalisation of access to abortion services. Economically, treasurer Rob Lucas tried to reign in government spending and, where possible, sought further privatisation or outsourcing of services, such as the Adelaide Remand Centre (ARC). South Australia was not as hard hit as the eastern states through the COVID-19 pandemic; neither lockdowns nor exposure rates were as significant in the state. Marshall’s government took a firm line on closing the state’s borders. In unfortunate timing, the Liberals re-opened the state’s borders in November 2021, which coincided with the Omicron wave of COVID.

Further to the poor timing of the border decision, the Marshall government lost the election for at least three key reasons. First, factional divides continued to bedevil the party. Second, Labor’s Peter Malinauskas is a charismatic leader, and demonstrated a stronger ability to seize political opportunities than Steven Marshall, capitalising on the Liberal government’s decision to cancel the Adelaide 500 motoring event. Third, Labor campaigned effectively on the under-resourced health services, and especially the ‘ramping crisis’ of backed-up ambulances unable to unload patients. The contours of the Malinauskas government are still evolving, but there is a relatively strong labourist economic policy agenda emerging — for example, Labor’s building of a Hydrogen power station in Whyalla. Yet, there is also the re-emergence of a more ‘populist’-style approach to criminal justice policy, especially when the government introduced new penalties for containing ‘disruptive’ protests, which caused backlash from human rights groups, unions and parts of the law community.

The influence of independents and minor parties

Examining governments only provides us with part of the story of South Australian politics. Independent MPs have long been a fixture of the South Australian Parliament, usually elected to the House of Assembly, and often representing rural, regional and outer suburban electorates. In many cases, independent MPs were often elected as members of one of the major parties (or were members of major parties denied preselection). The most significant impact of these independents has been in the process of government formation. Elections in South Australia regularly produce ‘hung parliaments’ where neither major party commands the majority of lower house seats needed to form a government. In these instances, independents and parties on the crossbench hold considerable sway over which party can form government. Since 1944, independents have played this role seven times, following elections in 1962, 1968, 1975, 1989, 1997, 2002, and 2014.

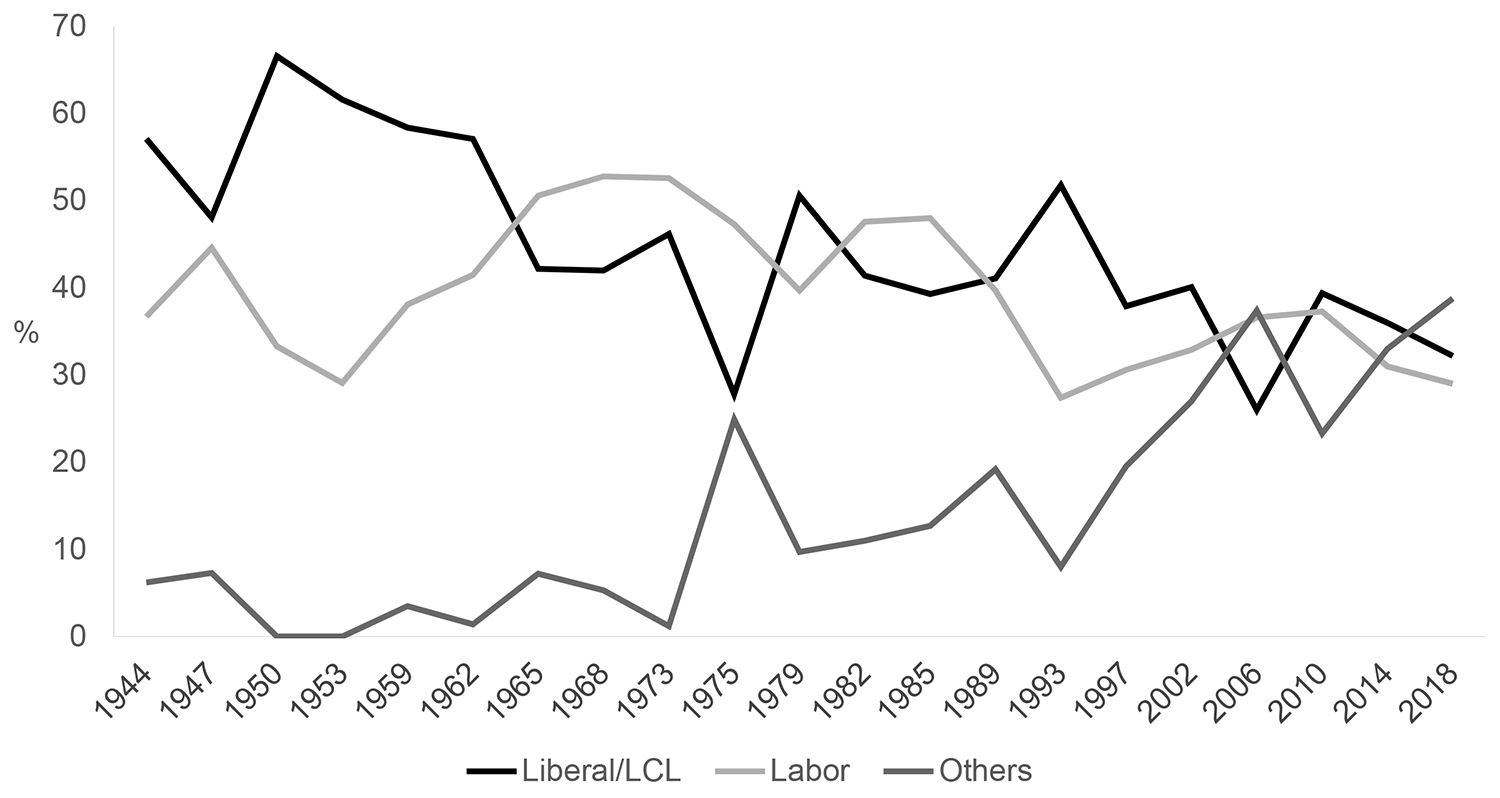

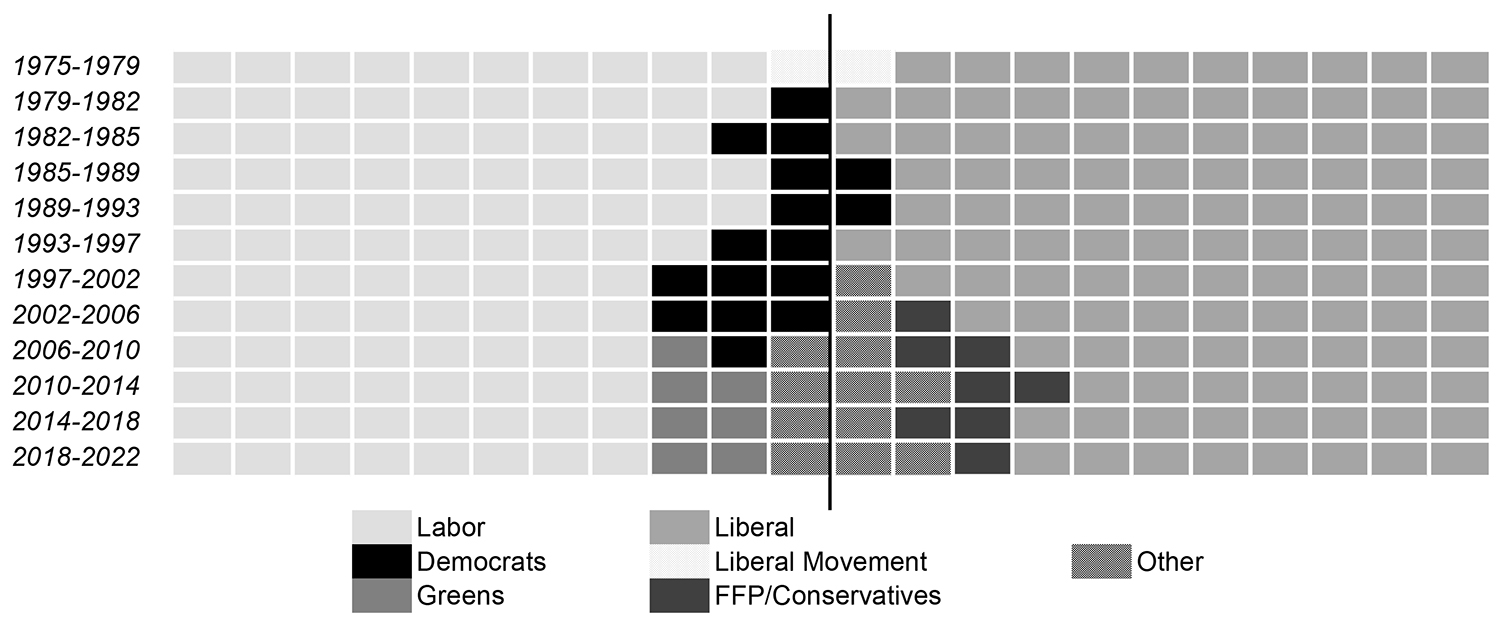

Minor parties have more often derived influence from their position in the Legislative Council. Until the mid-1970s, the LCL/Liberal Party dominated the Legislative Council due to restrictive voting rights that favoured the wealthy establishment and property owners. Following Dunstan’s electoral reforms introducing universal suffrage and a proportional electoral system, Labor and minor parties alike have secured greater representation in the upper house. For minor parties, as well, electoral reform contributed to a growth in their support. Figure 3 graphs the change in electoral trends.

Since 1975, the proportional electoral system has meant that minor parties have secured sufficient seats to play a decisive role in the Legislative Council. Minor parties have consistently occupied a balance of power role, meaning they can side with either the government or the opposition of the day (should they be at odds), and determine the fate of legislation. Thus, while these minor parties tend not to affect the formation of governments, they influence the function of governments. Since 1997, as well, this balance of power role has been shared among multiple minor parties, as depicted in Figure 4. What this means is that governments face a complex bargaining environment, needing to negotiate with and manage the interests of diverse, rival parties.

Key South Australian institutions and social actors

We group South Australia’s key institutions and actors into three main traditional types: governmental/public, private and ‘third sector’ (or non-governmental). The distinctiveness of South Australia’s institutional ecology is strongly shaped by its political history. The different political eras, as sketched out above, have been fundamental in shaping South Australia’s development. In its early years, the political system was infused with a radicalism and democratic innovation.[22] Given the historic economic challenges facing South Australia, a key focus of government (and the creation of related public institutions) has been active involvement in the economy. Though it has been a contested approach, the growth of South Australia’s economy has in major periods reflected the institutionalisation of government’s key role in development. [23] Beyond the immediate political institutions of Cabinet government, and the parliament, there has been an increase in reach and influence of statutory agencies and other public institutions.

A key moment in South Australia’s modern social transformation is observable in the institutional developments of the Labor Party during the 1970s under the leadership of Premier Don Dunstan. Through the creation of a number of statutory authorities, South Australia’s arts and tourism industries were institutionalised in an attempt to diversify the economy and make it more resilient to the emerging dynamics of globalisation. The Dunstan government’s statutory institutionalisation of new pathways for employment in these areas also served to develop a social, cultural and economic expression of the state’s experimental and progressive nature. In latter periods, for example under Premier Mike Rann, his government was underpinned by a number of key government boards and committees. A striking example was the Economic Development Board (created in 2002), which for a time had significant political influence, alongside the also powerful Social Inclusion Board.[24] More broadly, we can see a growth of the ‘regulatory state’, with public goods overseen by quasi-independent agencies and boards.

Second, the private sector remains a critical actor in the development of the state, and it is institutionalised through key actors. Pre-eminent among them is the South Australian Chamber of Commerce and Industry. Trading today as Business SA, this institution represents the interests of businesses in the state, chiefly in terms of managing industrial relations with employees and lobbying for institutional changes favourable to business, such as the removal or changing of regulation. At times it has played a significant political role, developing policy positions, commenting on state budgets, but also running campaigns — most notably leading the charge against a new proposed State Bank levy in 2017.

A third set of institutions are those often categorised as ‘third sector’ or non-governmental organisations (NGOs). South Australia, like many other parts of Australia, has a vibrant set of institutions that emerge from and seek to represent part of civil society. An important social institution is that made up of the array of organisations that fall within the South Australian labour movement. In 1876, South Australia was the first place in the British Empire to legalise trade unions, and they remain key actors in the South Australian political system. Today, SA Unions is the peak body of the union movement in the state. The key powerful trade unions remain affiliates of the state Labor Party. Outside of the union movement, one of the most prominent social actors is the South Australia Council of Social Service (ACOSS) which is an umbrella organisation for a suite of community sector NGOs and bodies. In common with other parts of Australia, increasingly social services are often contracted out to third-party providers.

How do we best understand the political power and influence of these institutions across the public, private and voluntary/community sectors in South Australia? This remains a key contested set of debates that has preoccupied political scientists for some time. Dye suggests that different ‘models’ of politics might help us understand power in different ways.[25] The most common model applied in Australia would be through the prism of pluralism. This model suggests that power is dispersed among different groups, and that government policy is often the result of trade-offs between, say, employer and employee groups. Other models, for example class-based approaches, suggest that, in a capitalist market economy, business groups have a built-in (structural) advantage and yield more influence, certainly more than trade unions. Other models note how, at times, different interests (e.g., business and labour) are institutionalised — in what is sometimes called a corporatist model. In the Rann era when representatives from the Economic Development Board and the Social Inclusion Commissioner were part of the Executive Committee of Cabinet, this seemed like a clear effort to build a form of corporatism.

Key controversies in South Australia

Democracy and accountability

Democracy is underpinned by two key principles: political equality and popular control.[26] Political equality entails that all groups of people have a voice within a given democratic system. Popular control means that, following Lincoln’s famous declaration, government should be ‘of the people, by the people, for the people’. Beetham and colleagues have often undertaken democratic ‘audits’ to see how well a country or polity is faring in this regard. A national audit of Australia was conducted in 2009, and for the first time, a democratic audit of the states has been conducted.[27] The health of South Australian democracy remains in question in at least three key areas: deliberation, accountability and governance.

In recent years, there has been a focus on ‘deliberative’ democracy.[28] The main claim made here is that voters should have more influence in between elections, and the quality of government decisions can be enhanced by greater public participation and discussion. Labor Premier Jay Weatherill was a noted advocate of this and instigated a range of ‘new’ deliberative techniques, including citizens’ juries. The effect of this has been mixed, with particular criticism directed at the citizens’ jury on the nuclear fuel cycle. Yet, it showed a rare willingness to enhance South Australia’s democratic institutions.

A second area of concern has been the issue of accountability — especially the mechanisms for holding the government to account. In the Cabinet system of government the convention of ministerial responsibility is critical.[29] This has two dimensions: collective and individual. In the case of the latter, the convention is that ministers are responsible for the workings of their departments, and, when things go wrong, they should resign (or more commonly be dropped or reshuffled). A number of scandals in South Australia, notably the Oakden abuse scandal, have drawn repeated attention to the growing ineffectiveness of individual ministerial responsibility.[30] It i unclear if overall levels of corruption and maladministration are worse in Australia, but the scandals tend not to receive as much national scrutiny as the larger states, and the State was one of the last to establish an Independent Corruption Commission.

A third area of concern, and not limited to South Australia, is the fragmenting nature of ‘governance’. Traditionally, the government and public sector (especially the main departments, e.g., education, health) were the main political and policy actors.[31] The shift from government to governance, however, entails a growth of statutory boards, commissions and councils (and the like) to deliver and oversee the outsourcing of public goods. Yet, there remains a concern about how effective these boards are, how accountable, and their relation to democratic institutions. For example, a number of scandals in health and the TAFE sector raise concerns about ‘arms-length’ institutions and their role.

Energy and nuclear power

Recent economic developments in South Australia have focused on debate around securing the state’s economic and energy future as the need to respond to climate change intensifies. Following an extreme weather event in October 2016 that left the entire state in blackout for hours, the Weatherill Labor government developed an energy industry policy to safeguard energy supply to homes and businesses in the event of future breakdowns in the existing energy grid. Through public–private partnerships with international energy companies Tesla and Neoen, the government has developed renewable energy infrastructure, further increasing South Australia’s national leadership on renewables and energy innovation. The initiatives under Premier Mike Rann institutionalised a nation-leading renewable energy policy and objective to increase renewable energy as a major source of supply. As at 2023, approximately 70 per cent of the state’s energy comes from renewable sources.

Recently governments have attempted to improve South Australia’s economic trajectory by seeking to make significant reforms in energy policy. Prior to the Labor government’s loss to the Liberal Party in 2018, Premier Weatherill had sought to explore options to establish a secure dumping site for nuclear waste in South Australia. The sequence of events relating to this highly contentious issue exemplified the responsible government principles and processes at the core of the state’s democratic institutions. There was a two-year process of a royal commission into SA’s participation in the nuclear fuel cycle and subsequent public consultation through a citizens’ jury. The final commission report handed down a decision in 2016 rejecting the idea. There also remain both scientific and political questions about the Malinauskas’s government focus on hydrogen energy.

Privatisation and state ownership

Privatisation refers to policies ranging from outsourcing of government services to the sale of public assets. Privatisation in Australia, and South Australia in particular, has a poor record, with questionable economic benefit and considerable social cost.[32] As governments began the process of privatisation in the 1980s, many voters responded with a relatively open mind. After all, there were inefficiencies and poor quality of service provided through some government-owned operations. Several decades on, public opinion tends towards scepticism about privatisation, with asset sales and outsourcing electorally risky. In particular, many voters appear unconvinced that privatisation leads to lower costs for consumers and are cynical about governments’ underlying rationale. Indeed, there are often different motivations underpinning calls for privatisation. A distinction has been made between pragmatic privatisation where public assets are divested in a drive for greater efficiency and a means of technical problem solving, and systemic privatisation which derives from an ideological commitment to reducing the role and size of government.[33] Privatisations under both Liberal and Labor governments have been propelled by both forms of these motivations at different times.

Despite the potential electoral costs, successive governments have pushed forward with asset sales and outsourcing. Most recently, the Weatherill Labor government privatised the Land Titles Office, the Motor Accident Commission, SA Lotteries, and forestry services. Further, the Marshall government in 2018 flagged the possibility of privatising some health and criminal justice services, while the Labor opposition claims the Liberals also have SA Water in their sights. The most controversial instance of privatisation in the South Australian setting, however, was the sale of the Electricity Trust of South Australia (ETSA) in 1999. This was the source of the contentious energy politics outlined above. Interestingly, it was the conservative Playford government that first established ETSA by nationalising privately-owned electricity assets in 1946. Fifty-three years later, it was Olsen’s Liberal government that broke up and sold the state-owned electricity suppliers, despite previous assurances to voters that such a sale would not occur. The ETSA privatisation would not have gone forward, however, without the support of two Labor members of the Legislative Council ‘crossing the floor’ to support the sale.

Conclusions

In some respects, South Australia has many of the main political features of other states, with its strongly bicameral parliamentary system, and the general dominance of the two major parties in terms of government formation. South Australia tends to be peripheral in national political debates, in part due to its smaller population and the pre-eminence of the larger, more economically powerful Eastern states. There are, in addition, lingering concerns that this populously small but geographically large state could be heading back to how it has often been traditionally viewed — as an economic ‘backwater’. Yet, this view of the state masks a long and often distinctive political history, with a notable radical tradition. South Australia was an early, and indeed global, leader in democratic innovations. It has distinctive political institutions, for example the powers of its Upper House are stronger than many of the other state counterparts.[34] Moreover, it has been the origin source of new political movements in the nation’s history, including the Democrats and Family First. The Malinauskas government was the first in the nation to introduce a Voice to Parliament, and the state has often been a site for policy innovations, for example, leading a focus on social inclusion in the 2000s.[35]

There are also intriguing developments in South Australia’s party system. Like the other states and territories there has been a marked growth in the vote share of minor parties, but a more striking pattern is that in 2022, the South Australian electorate has, yet again, returned a Labor government to power. Since the 1980s, Labor has dominated South Australian politics. One factor that might explain this trend is that South Australia may not necessarily be more left-leaning than other parts of Australia, but rather at the state-level, South Australian voters are prepared to reward activist and interventionist governments. Given the financial constraints and the relatively small size of the state’s economy, voters have tended to look to government to help stimulate economic activity, especially through infrastructure-building. This is a non-partisan tradition in South Australia and harks back to the Playford era.

Revision questions

-

What is electoral malapportionment? How has it affected South Australian politics?

-

What have been the major political eras in South Australia’s history? Which do you think have been the most important?

-

How would we know if South Australia’s democratic system is working well? What, if anything, can be done to improve it?

-

What are the major controversies that are taking place within South Australia?

-

How useful is it to think about South Australian politics through the Labor/non-Labor axis? How influential are the minor parties?

-

Which are the major institutions in South Australia shaping its politics and economics? Which do you think are the most influential, and why?

References

Aulich, C. and J. O’Flynn (2007). From public to private: the Australian experience of privatisation. The Asia Pacific Journal of Public Administration 29(2): 153–71.

Beetham, D. (1994). Key principles and indices for a democratic audit. In D. Beetham, ed. Defining and measuring democracy, 25–43. London: Sage.

Bevir, M. (2012). Governance: A very short introduction. Oxford: OUP.

Blewett, N., and D. Jaensch (1971). Playford to Dunstan: the politics of transition. Melbourne: Cheshire.

Brett, J., 2019. From secret ballot to democracy sausage: How Australia got compulsory voting. Text Publishing.

Cahill, D. and P. Toner (eds.) (2019). Wrong way: how privatisation and economic reform backfired. Carlton, Vic: La Trobe University Press.

Church, N. (2018). South Australia state election 2018. Research Paper, 17 July. Adelaide: Parliament of South Australia.

Cockburn, S. and J. Playford (1991). Playford: benevolent despot. Kent Town, SA: Axiom.

Crump, R. (2007). ‘Why the Conference Procedure remains the preferred method for Resolving Disputes Between the Two Houses of the South Australian Parliament’. Australasian Parliamentary Review 22(2): 120-16.

Dryzek, J.S. (2002). Deliberative democracy and beyond: Liberals, critics, contestations. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Dye, T. (2013). Understanding public policy. Boston: Pearson.

Jaensch, D. (1976). A handbook of South Australian government and politics, 1965–1975. Occasional monograph no. 4. Bedford Park, SA: Self-published.

——— (1977) The Government of South Australia. St Lucia: University of Queensland Press.

——— (2011). Democratic representation: then, now, and in the future. Paper presented to public lecture series: SA 175: Exploring the Past, Shaping the Future, 25 October. Flinders Journal of History and Politics 27: 26–34.

Lynch, S. (2016). Electoral fairness in South Australia. Working Paper 38. Melbourne: Electoral Regulation Research Network/Democratic Audit of Australia Joint Working Paper Series.

Macintyre, C. (2005). Politics. In J. Spoehr, ed. State of South Australia, 117–32. Adelaide: Wakefield Press.

Martin, R. (2009). Responsible Government in South Australia: From Playford to Rann. Adelaide: Wakefield Press.

Manning, H. (2005). Mike Rann: a fortunate ‘king of spin’. In J. Wanna and Paul Williams, eds. Yes, Premier: Labor leadership in Australia’s states and territories. Sydney: UNSW Press.

Manwaring, R. (2016). The renewal of social democracy? The Rann Labor government 2002–11. Australian Journal of Politics and History 62(2): 236–50.

Orr, G. and R. Levy (2009). Electoral malapportionment: partisanship, rhetoric and reform in the shadow of the agrarian strong-man. Griffith Law Review 18(3): 638–65.

Parkin, A., and A. Patience (1981). The Dunstan decade: social democracy at the state level. Melbourne: Longman Cheshire.

——— (1992). The Bannon decade: the politics of restraint in South Australia. St. Leonards, NSW: Allen & Unwin.

Parkin, A. and A. Jaensch (1986) South Australia. In B. Galligan, ed. Australian state politics, 98–115. Melbourne: Longman & Cheshire.

Parliament of South Australia (n.d.). List of South Australian firsts. Adelaide: Parliament of South Australia. www.parliament.sa.gov.au/ABOUTPARLIAMENT/HISTORY/TIMELINEORSOUTHAUSTRALIANFIRSTS/Pages/TimelineForSouthAustralianFirsts.aspx

Payton, P. (2016). One and all: Labor and the radical tradition in South Australia. Adelaide: Wakefield Press.

Rann, M. (2012). Politics and policy: states as laboratories for reform. Speech to the ANU, 10 May. Canberra: Australian National University. https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B6C8ErPybM4_N0xoS1hTeEZPWDQ/view

Sawer, M., N. Abjorensen and P. Larkin (2009). Australia: the state of democracy. Sydney: Federation Press.

Selway, B. 1997. The Constitution of South Australia. Sydney: Federation Press

Sheridan, K., ed. (1986). The state as developer: public enterprise in South Australia. Adelaide: Royal Australian Institute of Public Administration.

Spoehr, J. (2005). State of South Australia: trends & issues. Kent Town, SA: Wakefield Press.

——— (2009). State of South Australia: from crisis to prosperity? Kent Town, SA: Wakefield Press.

Stutchbury, M. (1986). State government industrialisation strategies, In K. Sheridan, ed. The state as developer: public enterprise in South Australia. Adelaide: Royal Australian Institute of Public Administration.

Thompson, E., and G. Tillotsen (1999). Caught in the act: the smoking gun view of ministerial responsibility. Australian Journal of Public Administration 58(1): 48–57.

Wanna, J. (1986). The state and industrial relations in South Australia. In K. Sheridan, ed. The state as developer: public enterprise in South Australia. Adelaide: Royal Australian Institute of Public Administration.

About the authors

Dr Rob Manwaring is an Associate Professor in the College of Business, Government and Law at Flinders University in Adelaide, South Australia. Rob teaches Australian politics and public policy and researches into the areas of political parties, and social-democratic politics. He is the co-editor of Why The Left Loses: The Decline of the Centre-Left in Comparative Context (2018).

Dr Josh Holloway is a Lecturer in the College of Business, Government and Law at Flinders University in Adelaide, South Australia. Josh teaches comparative politics, and his research covers democratic resilience, party politics, and electoral administration.

Dr Mark Dean is a research associate at the Australian Industrial Transformation Institute at Flinders University. He researches the impact of digital technologies and the ‘fourth industrial revolution’ on the future of employment, work and society. His research interests include Australian and international industry and innovation policy, and SA politics.

- The original version of this chapter was co-written with Mark Dean (former Research Associate at Flinders University). This version builds upon and extends this chapter. Manwaring, Rob, Mark Dean and Josh Holloway (2024). South Australia. In Nicholas Barry, Alan Fenna, Zareh Ghazarian, Yvonne Haigh and Diana Perche, eds. Australian politics and policy: 2024. Sydney: Sydney University Press. DOI: 10.30722/sup.9781743329542. ↵

- Rann 2012. ↵

- Parliament of South Australia n.d. ↵

- Selway 1997. ↵

- Parliament of South Australia, ‘SA Firsts’; see also Brett 2019. ↵

- Martin 2009. ↵

- Crump 2007. ↵

- South Australia’s constitution stipulates that this would require a referendum to be held. ↵

- Details for the electoral systems can be found at the SA Electoral Commission’s web-site: www.ecsa.gov.au ↵

- Orr and Levy 2009. The term ‘Playmander’ is derived from Thomas Playford (South Australian Premier 1938–65, and leader of the Liberal and Country League) and ‘Gerrymander’, which is itself a portmanteau of ‘Gerry’ and ‘salamander’. ↵

- Lynch 2016, 7. ↵

- Church 2018. ↵

- Jaensch 2011; Jaensch 1977; Jaensch 1976. ↵

- Jaensch 1977, see chapter 3. ↵

- Parkin and Jaensch 1986, 100. ↵

- Blewett 2012; Manwaring 2016. ↵

- Parkin and Patience 1992. ↵

- See concluding chapters in Parkin and Patience (1992) for different views on Bannon’s record in office. ↵

- As such, Brown versus Olsen leadership struggles can be seen as stemming from unresolved factional divides since at least the 1960s. ↵

- Spoehr 2005, 2009. ↵

- Macintyre 2005. ↵

- Payton 2016. ↵

- See chapters by Michael Stutchbury and John Wanna in Sheridan (1986). ↵

- Manning 2005. Under the Marshall government, the Economic Development Board was folded into a new, smaller Economic Development Agency. ↵

- For a further discussion of different models of politics – see Dye 2013. ↵

- Beetham 1994. ↵

- Sawer, Abjorensen and Larkin 2009. The fieldwork for the most recent audit was conducted in 2021–2022 and is due to be published in 2024. ↵

- Dryzek 2002. ↵

- Thompson and Tillotsen 1999. ↵

- The Oakden nursing home was a state-run mental health centre for older people, which was eventually shut down in 2017 after allegations of abuse and neglect were found against residents. The Oakden scandal was one of the drivers for the federal government to begin in 2018 a royal commission into aged care quality and safety. ↵

- In political science there is a debate about the shift to ‘governance’, which can entail a shift away from government hierarchy to the greater role for markets, and crucially, networks. See Bevir 2012. ↵

- Cahill and Toner 2018. ↵

- Aulich and O’Flynn 2007. ↵

- Crump 2007. ↵

- Spoehr 2005. ↵