27 Social movements

Justine Lloyd

Key terms/names

civil society, collective action, cycles of contention, framing, mobilising structures, political opportunities, public sphere, repertoires of contention, state imperatives, trigger events, WUNC (worthiness, unity, numbers and commitment)

Introduction

Social movements[1] are behind many of the democratic political changes we now take for granted in Australia. From the 1890s, for example, Australian unions and women’s organisations called for equal pay for equal work. In the early 1970s the Australian Conciliation and Arbitration Commission finally instituted laws requiring women’s pay to be equal to men’s pay for the same kind of work. Concerted efforts by movements of ordinary people outside the formal political system just like these continue to challenge governments and political parties to change unjust policies and practices.

Knowing about how social movements emerge and how they make social change is critical to understanding how processes of democracy, government and policy making interact. This chapter discusses what social movements are, when they form, who joins them and why, how they work, and why they cease to exist. Looking critically at social movements helps us understand how the political systems that movements operate within shape them, and how movements themselves use these contexts to maximise their chances of success. These considerations shine a light on some of the important theories about the role of the state in a democratic society. The chapter also reflects on whether all of these groups are good for democracy and discusses the emergence of a variety of social movements in Australia.[2]

What are social movements?

The term ‘social movement’ refers to loose coalitions of ordinary people, often ‘in alliance with more influential citizens and with changes in public mood’,[3] who join forces to make broad social change. Political sociologist Charles Tilly, who described a social movement as ‘a sustained challenge to power holders in the name of a population living under the jurisdiction of those power holders’,[4] emphasised how these movements emerge from the formal and informal relationships between political entities, especially nation-states, and the people that they represent.

Tilly’s focus on the sustained nature of social movement activity also highlights that, while such movements may ebb and flow depending on internal and external conditions (what these conditions are is explored in the next section), movements are very different from one-off forms of protest. Social movements may coordinate temporary events such as rallies and marches, which might attract large crowds, but they are much more than sudden gatherings of disgruntled citizens.[5] Movements are made up of actively involved participants who come together across time and across space to coordinate such events: for example, by joining meetings to plan actions to target multiple politicians across electorates. Social movements even at times coordinate with other like-minded groups across neighbourhoods, cities, nations or even the globe.

Recently social movement scholars have built on Tilly’s definition to explore how such movements increasingly focus on organisations and institutions beyond the state. Important targets of social movement action now include corporations and private employers, as well as the more invisible power relations implicated in the ‘realms of culture, identity, and everyday life’.[6] This expanded and more inclusive definition captures how social movements form to challenge or defend ‘extant authority, whether it is institutionally or culturally based, in the group, organization, society, culture, or world order of which they are a part’.[7] Examples of these kinds of movements are the African-American–led civil rights movements that emerged in the 1960s. Through the slogan ‘Black is Beautiful’, these movements not only sought to challenge institutional forms of racism in discriminatory laws and state policies, but also to confront internalised racism in African-American communities: for example, by promoting ideas of Black Pride and celebrating African-American heritage and cultural autonomy.

Why do they form?

Social movements emerge from political, social, economic and cultural conflicts. As John Dryzek has argued in the Australian context, during the 19th and 20th centuries, social movements emerged from very concrete power imbalances between those who controlled and made decisions within the political system and those who were excluded because of their economic status, citizenship or role in the gender order.[8] This lack of representation in the formal political system led to marginalised groups, such as the working class, women, immigrant communities and Indigenous peoples working collectively and tabling claims for formal inclusions within the state. Inclusion within the state is key to ensure laws and policies to deal with cultural and historical injustices: for example, in the ongoing struggles of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples to have rights to land (as explored in the case study below).

In Australia, pressures for formal inclusion have led such social movements, but at the same time inclusions for one group has led to other kinds of exclusions, which in turn have generated further social movement–led claims. Dryzek points out, that around the time of Federation, working-class white men came together to promote their political and economic interests through organisations such as labour unions and local socialist parties, leading to what has been called the formation of a ‘wage-earners’ welfare state’.[9] Previously working men had been excluded from voting, and therefore inclusion in the state, because many states had only allowed men who owned property to vote.[10] At the time, ideas of representative democracy, combined with racial ideologies linked to colonialism and British imperialism, led to the lessening of restrictions on property ownership as a requirement for voting for white men.

While the suffragists successfully pushed for women’s rights to vote and stand for office, one of the first acts passed by the Federal Parliament had been the 1901 Immigration Restriction Act, later known as the ‘White Australia’ policy, which prevented the immigration of non-white people, particularly from Asia, on the basis of a dictation test that could be posed in any European language. Thus, while white working men and white women, experienced inclusion, non-white immigrants as well as Indigenous peoples experienced exclusion in the formation of the Australian state.

Indigenous social movements

Formal inclusions, when they take place, are often linked to other forms of discrimination, such as those experienced by Indigenous peoples in Australia, and Indigenous-led social movements have existed in Australia since colonisation. While Indigenous peoples have had the right to vote since the 1960s, they continue to experience other forms of exclusion and discrimination from the state, as well as within the economy, and through cultural institutions such as education.

Indigenous peoples, via their representative groups and communities, such as the Australian Aborigines League in the 1930s and the Australian Aboriginal Fellowship in the 1950s and 1960s, have highlighted the institutional racism of historical and contemporary state policies since 1788. The ongoing effects of such institutional racism include, but are not limited to, the impact of state-regulated mining licences and operations on culturally significant sites, the ongoing legacies of assimilationist policies such as through the Stolen Generation, the authoritarian control and stigmatisation of communities through the welfare system including the 2007 Intervention in the Northern Territory and income management (via the introduction of the Basics Card), as well as over-incarceration and the systemic racism of the criminal justice system, which are reflected in the high rates of deaths in custody of Indigenous people. These ongoing exclusions have driven the formation of Indigenous-led social movements and claims for self-determination since colonisation.

Dryzek explains that the inclusion of groups, such as Indigenous people in settler-colonial states such as Australia, will always be limited by inherent conflicts between a social group’s defining interests and core state imperatives, which are ‘any function that structures of government must perform for the sake of their own longevity and stability, thus responding to exogenous parameters and existing independent of the preferences or desires of government officials’.[11] Indigenous peoples’ struggles in Australia to have local and enduring connections to land and formal land rights recognised in law and practice can be seen to directly conflict with the state imperatives of control over its territory and exploitation of resources, which the Australian state defends alongside liberal ideas of property ownership and the exploitation and commodification of nature for individual profit. These imperatives are embedded in Western legal and political systems and reflected in the way that the Australian state currently limits full constitutional recognition of Indigenous peoples’ systems of knowledge and justice.

Yet, as Dryzek also points out, ‘economic imperatives clearly benefit from the removal of racial discrimination, which is an impediment to the free operation of the market (especially the labour market)’,[12] and much of the success of Indigenous social movements – as well as class- and gender-based movements – have indeed been in instances where such movements call for barriers to economic participation to be removed. Recent conversations about the Uluru Statement’s call for constitutional recognition of Indigenous peoples in the Australian political system have focused on these limits to the state’s openness. It remains to be seen how the Australian state will respond in relation to these important calls for change and the broad-based social movement that is forming around these issues.

Who joins and why?

Social movements may develop as people accept changing attitudes on an issue and realise the injustice of certain laws through ‘trigger events’,[13] such as in the violent police actions to disperse the 1978 Mardi Gras parade, which followed a more conventional Gay Solidarity march earlier on the same day.[14] Reactions to the police’s actions led to further local trigger events within a global movement for lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, intersex and more (LGBTI+) rights, which then led to the decriminalisation of homosexuality in the 1980s in Australia. This was followed by the worldwide movement for marriage equality in the late 1990s and early 2000s. Another recent example of interlinked trigger events was the 2013 acquittal of George Zimmerman in the shooting death of Trayvon Martin in 2012, which in turn led to the formation of the Black Lives Matter movement, which later picked up momentum in response to the death in custody of George Floyd in 2020.

Because a political voice is required to address social exclusions, struggles over who is and is not allowed political citizenship have emerged as groundswells of action, such as in the refugee rights movements that began in the 1930s and which has continued well after the end of the Cold War and into the current era of Islamophobia. The emergence of counter-movements, or opinions mobilised in opposition to a social movement (e.g. the men’s rights movement in reaction to feminism), are seen to be a sign of the movement’s consolidation of alternatives to the status quo.

Collective action

Collective action is intrinsic to social movements because they build out from individual beliefs and meanings about social and political issues to form shared understandings of an issue.[15] While individual people and organisations within movements may have diverse motivations and even contradictory ways of going about solving a social issue, they will share common rituals and a sense of purpose. This sense of purpose needs to be broader than that of any one organisation or formal group to allow ordinary people to take part in a meaningful way to resolve their concerns. Recognition of the source of the conflict itself as outside the movement or individuals themselves is also essential to allow movement actors to section off cultural and ideological differences and undertake coordinated action.

Successful contemporary social movements, therefore, tend to have high levels of participation by individuals with these characteristics:

- don’t necessarily see themselves as part of a formal organisation

- self-identify with the cause or issue of concern

- partake in a collective identity that involves a loosely shared agreement about the way to solve this issue, for example seeing oneself as a feminist, an environmentalist or a progressive

- see political or ideological opponents as ‘enemies’ to overcome

- act via links between formal and informal ‘social movement organisations’ within this wider tapestry of informal participation.

In practice, there is considerable overlap between broad-based social movements and formalised political organisations. Often what begin as social movements later spawn political parties as they seek to consolidate forms of political participation. Likewise, some groups that may form as pressure groups to deal with a policy issue may focus their effort on broad-scale mobilisation and changing public opinion as a way of bringing about the policy change that they seek on a specific issue. For example, the campaign for marriage equality in Australia began as a pressure group (stemming out of the LGBTI+ rights movement, which had already sought broad legal and policy change). As the quest for marriage to include non-heterosexual couples gained traction in the broader community, support for marriage equality became a social movement.

Collective action and free riders

This leads to debates about how public-spirited movements are. Mancur Olson’s classic study of why individual actors get together to act collectively argued that such action is primarily motivated by desire for individual benefit, but a benefit not available to a person acting alone.[16] This ‘rational choice’ approach focuses on the cost–benefit calculation of members in joining groups and movements. In this model, groups form because some individuals perceive opportunities to receive a share of the public benefit, possibly at the expense of other, less complex and time-consuming pathways, that might deliver greater individual returns: for example, by joining a union rather than relying on backroom deals with the boss for individual pay rises.

This approach also explains paradoxes in group formation: if groups produce public benefits that all can access, what is the incentive of participation for the individual? If groups become too large, some may benefit without paying the costs of the group. This problem of ‘free riding’ can be seen in the way some groups attempt to restrict the benefits of their collective action to their membership, such as when unions historically enforced ‘no ticket, no start’ requirements that workplaces must employ only union members.

Justice and altruism

Other approaches emphasise that groups are not simply aggregations of individuals calculating costs, and that social movements by acting collectively question the very idea of whether social progress is indeed reducible to a cost–benefit calculation.[17] An important critic of the ‘rational choice’ model and its focus on individuals through a purely economic lens was the English historian E.P. Thompson.[18] By studying the history of social movements from ‘below’ – that is, from the perspective of the poorest people in the transition from feudal to free-market economies during the 18th and 19th centuries – Thompson found that:

common people shared an ethic based on reciprocal exchange of gifts and services and redistribution in times of need, rather than individual pursuit of self-interest, and that their consistent actions in defense of this ethic, although seemingly random and unspectacular, entitle them to ‘be taken as historical agents’.[19]

Scholars such as Thompson observe that rational choice fails to explain participation, especially at the early stages of movements when chances of immediate success are limited, or recognise the role of non-economic principles such as ethics, justice and morality in tempering the ‘selfish’ motivations of individuals and limited membership groups.

How do they work within the political system?

What distinguishes social movements from political parties and other advocacy groups, such as charities, is the way that social movements instigate and coordinate collective action. Social movements work towards their shared goals across the informal grassroots relationships and formal organisations in a way that is broadly independent from government and commercial interests. Collectively the elements that make up this social world – formed of activist groups, voluntary associations and religious organisations – are known as civil society. Political parties can overlap with and emerge from, but in the end fundamentally differ from, civil society because they are specifically organised to mobilise electors to influence policy by gaining power and forming government via the part of the state that is most responsive to its citizens, the legislature. Social movements usually consider a much wider set of targets, as discussed above.

While professional advocacy organisations are also part of civil society, social movements can be contrasted with interest groups such as think tanks and business associations in three important ways:

- because social movements originate in the concerns of ordinary people they by definition actively involve a grassroots membership rather than elites

- either because social movements lack ‘access to political institutions … or because they feel that their voices are not being heard’, unlike interest groups they must strategically employ ‘novel, dramatic, unorthodox, and noninstitutionalized forms of political expression’ to achieve their goals or express dissent[20]

- linked to these two previous factors, social movements are usually not recognised as legitimate political actors and have to undertake multiple forms of action towards the state, both inside and outside traditional channels of democratic participation.[21]

Thus, as Snow, Soule and Kriesi argue (after Gamson), social movements display creative strategies and breadth and diversity of membership because ‘interests groups and politically oriented social movements are not so much different species as members of the same species positioned differently in relation to the polity or state’.

Because social movements emerge from the public sphere, rather than being integrated within or initiated by the state, their tactics and strategies reach beyond making government policy to try to change society more broadly. Social movements are also inherently oppositional and can therefore be seen as on a continuum with other, older and more radical forms of ‘contentious politics’ such as riots over food, peasant revolts and political revolutions.[22] According to Tilly, modern social movements are usually distinguished from these earlier kinds of contention in three important ways:

- their political goals are not just ‘parochial’, or focused on one community and its power imbalances, but rather are ‘cosmopolitan’ and therefore span many locations and centres of power

- their forms of action are ‘modular’ and easily transferred from one setting or circumstance to another, on a national and international scale rather than ‘segmented’ (that is, being crafted to tackle a single local representative)

- finally, they are ‘autonomous’, rather than ‘particularistic’ in the kinds of action that they because they establish direct contact between local claimants and nationally significant centres of power.[23]

One of the other distinguishing features of the sustained challenges of social movements is how social movement actors display their strength to, and demand responses from, authorities. Tilly observes that social movements activists, like other actors in the public sphere, including political parties and advocacy organisations, tirelessly work behind the scenes and in public, either within their own organisations or across several organisations to plan ‘joint actions, [build] alliances, [struggle] with competitors, [mobilise] supporters, [build] collective identities, [search] for resources and lobby’ authorities. But what distinguishes social movement forms of action is that at least one member group of a broader challenger coalition publicly displays strength to authorities via the formula that Tilly terms ‘WUNC’, an acronym that is shorthand for worthiness, unity, numbers and commitment.

Tilly even poses WUNC as a mathematical formula for the (metaphorical) strength of the movement:

movement strength = worthiness x unity x numbers x commitment

Tilly argues that ‘If any of these values falls to zero, strength likewise falls to zero; the challenge loses credibility’, while ‘high values on one element … [can] make up for low values on another’. Here Tilly is highlighting how

a small number of activists who display their worthiness, unity, and commitment by means of simultaneous risk or sacrifice [for example in a hunger strike or other form of risky action], often have as large an impact as a large number of people who sign a petition, wear a badge, or march through the streets on a sunny afternoon.[24]

The public display of WUNC requires social movements to demonstrate evidence of each factor within this formula, either spontaneously or in a crafted and deliberate way. Thus social movements show worthiness by dressing formally during public meetings or demonstration, incorporating faith or community leaders and other high-status allies into their actions, as well as elderly or differently abled members, and tabling grievances by highlighting previous and ongoing injustices. Signs of unity include wearing similar colours, or even uniforms, marching or dancing in unison, chanting slogans, singing, cheering, linking arms, or wearing or bearing common symbols such as T-shirts, badges, armbands, headgear or placards. Demonstration of numbers includes coordinated occupations of public space, gathering signatures on petitions, representing multiple units into a cohesive whole (for example, a public gathering of all local neighbourhood associations across a single city), as well as forms of quantifiable support by means of publishing polls, the number of paid-up members and overall financial contributions. Finally, indications of commitment include persisting in costly or risky activities such as going without pay during a strike or standing up to a state’s monopoly of violence by stopping police or military actions, as well as declarations and proof of readiness to persevere via open-ended and disruptive actions such as sit-ins, or even resistance to attack such as forming a picket line or including human rights observers in protests.[25]

Sociologist Sidney Tarrow observed that major societal changes such as war, recession, political instability or large demographic or technological changes often prompt ‘cycles’ or ‘waves of contention’ that give rise to social movements whose members act in these ways.[26] Much of the shared know-how of successful social movements rests on how to ride out these waves and to build them into widening cycles by making the impact of protest long-lasting through coordinating deeper systemic and political change, and even, at times, transforming state imperatives. Understanding the outcomes of these waves requires an understanding of how factors outside social movements influence the kinds of changes they seek to make, and also their chances of success or failure, which are seen to be guided by three interlocking factors: changes in external political factors; the means by which people are mobilised; and the cultural construction of issues and identities, all of which we turn to in the next section.

Political opportunities

Political opportunity is a key explanation of why movements form and how they build their effectiveness. This theory, in contrast to earlier theories of ‘resource mobilisation’, emphasises that beyond the internal resources of ‘money or power’, which movements often lack in comparison to powerful actors such as business or autocratic political leaders, there are resources critical to social movement groups that ‘can be taken advantage of by even weak or disorganised challengers but in no way “belong” to them’.[27] Seen through this framework, social movements, in order to be successful, must be alert to and grasp favourable political conditions when they emerge (see Table 1). Taken together these external conditions are known as the political opportunity structure facing any given movement.

| Non-structural (mutable, unstable, subject to pressure from movement) | Structural (fixed, stable, beyond movement control)[29] | ||

| Threats | State’s increasing capacity and propensity for repression (e.g. Parliament introduces new laws raising penalties for protest and criminalising strikes) | Elite alignments that undergird a polity moving against the claimants (e.g. fossil-fuel sector makes large political donations to incumbent government with a view to decelerating climate change policy) | Relative closure of the institutional political system (e.g. vote suppression tactics lead to disenfranchisement of claimant groups or military coup installs authoritarian regime and calls off elections) |

| Opportunities | State’s decreasing capacity and propensity for repression (e.g. media coverage of a peaceful protest highlights indiscriminate use of violence by police against claimants) | Elite alignments dissolve and some elements move towards supporting the claimants (e.g. strategic use of social media by feminists highlights sexual harassment in both government and business sectors, resulting in cleavages between and within both over women’s rights) | Relative openness of the institutional political system (e.g. authoritarian head of state dies and new leader calls open elections or a widespread health crisis leads to democratic inclusion of previously excluded claimants) |

These conditions can include fluctuations of the political environment that are subject to pressure from movements themselves, such as changes in government, which in turn can either increase or decrease access to the state depending on whether political parties or leaders linked to social movements are elected or ejected. These conditions are described as non-structural, because they are not fixed and are more open to pressure from below.

Other conditions favourable or hostile to movements are seen as structural, because they are beyond a movement’s direct control. Examples of structural opportunities include a political legitimation crisis provoked by an economic downturn, when elites who may have traditionally been united against the contenders become divided; or when powerful new allies emerge with the rise of new forms of social organisation, such as in new class formations reflected in new forms of work and wealth generated by technological change. But structural aspects of the political system can also include more routine factors, like the openness of institutions to petitioning, litigation, hearing voices of movement actors at parliamentary inquiries or Royal Commissions, or other forms of political practice that groups and movements have expertise in.[30]

The final, and most risky, aspect of the political opportunity structure is the willingness of the state to contain and repress social movements by the use of force, which constitutes a direct threat to civil liberties and, potentially, human lives. Shifts in either direction in this last aspect in authoritarian states are crucial for movement actors to assess and understand, because the increasing or decreasing propensity of the executive arm of the state to deploy police or military in internal conflicts will quickly close down or open up movement leadership and discourage or encourage further mobilisation. But these factors are also at play in more socially acceptable ways in democratic states, where the state’s monopoly of violence still exists, and may manifest in new laws to outlaw certain types of protest, such as has been seen in the early 2020s in New South Wales with the introduction of strict anti-protest laws targeting direct action groups such as Blockade Australia.[31] The next section explores how such groups provide the collective vehicles for social action, linking the lived experiences of exclusion or injustice with the wider political environment.

Mobilising structures

While the external factors encapsulated in the political opportunity model clearly influence how social movements themselves form and reform the society that they are part of, organisations would not, without effective internal structures and cultures, be able to shape and respond to these ever-evolving opportunities. To take advantage of opportunities, and mediate between individual grievances and the political sphere, successful movements need ways of making decisions and acting collectively. To understand why and how groups form within a wider social movement and further constitute that movement, we now turn our attention to the role of organisations.

Social movement theorists argue that movements are more than an aggregation of individuals, but spring from people organised into both formal and informal entities. These building blocks of social movements are termed mobilising structures, which are the collective vehicles through which people come to mobilise and engage in collective action (see Table 2).[32] These structures range from formalised groups with highly exclusive membership, such as being a member of an specific industry and active in one’s workplace in order to join a union, or being prepared to pay dues and be involved in high-impact protests to be part of an environmental organisation. Inclusive membership, on the other hand, is seen in churches and media-based campaigns, in which structures might be composed of informal networks of friends and neighbours who come together around a shared experience or concern.[33]

|

Type |

Formalised |

|---|---|

|

Membership |

exclusive membership requirements, i.e. members subject to:

|

|

Benefits |

|

|

Limitations |

|

|

Tendency over time, if unchecked |

|

|

Examples |

|

|

Type |

Formalised |

|

Membership |

inclusive membership:

|

|

Benefits |

|

|

Limitations |

|

|

Tendency over time, if unchecked |

|

|

Examples |

|

|

Type |

Informal |

|

Membership |

membership based on:

|

|

Benefits |

|

|

Limitations |

|

|

Tendency over time, if unchecked |

|

|

Examples |

|

Organisations with exclusive membership may generate very tight bonds between members because the very reason for the organisation’s existence may be reflective of deeply felt and widely shared commitments. Organisations with inclusive membership may have less common ground in a political issue, but they also will have lower barriers for members to join and participate in the activities of the group. Informal networks are effective catalysts for social movement action but will often struggle to act at scale and in public and formal political settings, unless they are sensitive to the need to build democratic processes of decision making and ensure that they collaborate with other groups.[39]

Formalised and exclusive organisations may also have to work hard to maintain relevance and bonds of trust with their membership. This is especially a challenge if they employ staff and start to divide activity between ‘ordinary’ and ‘professional’ activists. The pressures of maintaining the organisation itself may eventually see its leadership becomes desensitised to members’ everyday worries and hopes for the future, which will therefore decrease its overall effectiveness and responsiveness over time. Jane McAlevey has recently analysed what makes exclusive membership organisations such as unions effective. She distinguishes between organisations with limited efficacy because they employ a professional staff base that focuses on ‘advocating’ on behalf of or ‘mobilising’ members, versus more successful organisations that build power by continually expanding who sits in negotiations with power-holders by ‘organising’ members.[40] Her analysis demonstrates that organisations that involve members in clear steps to mass participation are more successful in getting claims heard as well as more sustainable in the long term.

This focus on organisations as nodes within social movement networks highlights that effective action needs to focus on not just why people come together to make social change, but also how they come together. This focus on structures gives rise to the question of ‘what’ social movement action is about, and the important question of how social movements define the terrain of social conflict is explored in the next section.

Framing

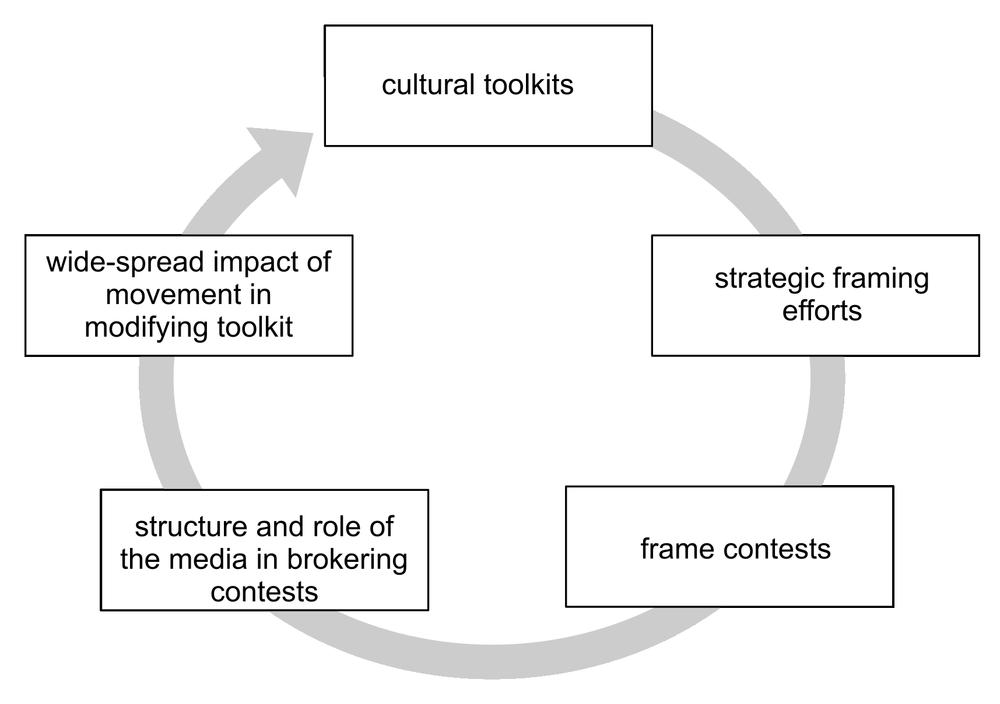

Literature about social movements sheds light on the way that issues are ‘framed’ by organisations to garner support for a social movement or for policy change. Framing refers to how groups link interpretations of individual interests, values and beliefs with their activities, goals and ideology (see Figure 1). Gitlin provides a useful definition of framing and its role in shaping our perceptions of the social world when he describes frames as

principles of selection, emphasis, and presentation composed of little tacit theories about what exists, what happens, and what matters … we frame reality in order to negotiate it, manage it, comprehend it, and choose appropriate repertoires of cognition and action.[41]

Because they routinely question dominant frames, movements need to actively negotiate shared understandings of a problem that might have been previously invisible or lacked a language to express.

As Jenny Kitzinger has argued, the concept of framing builds on, but involves much more than, the traditional notion of agenda setting in media and politics because ‘it acknowledges that any account involves a framing of reality’.[42] Frames, typically in a narrative form, structure the focus of an event or situation, and seek to direct emotions and energy accordingly. Narratives use stories to associate events and experiences, making meaning relatable and enhancing the message for a collective purpose. The framing process within social movements moves emotional states and experiences of anger, shame or hope towards collective, action-oriented, political directions.[43] Social framing usually undertakes three important ‘tasks’:

- defining the problem to be tackled, through ‘diagnostic’ framing

- proposing a solution to this problem via ‘prognostic’ framing

- finally, using ‘motivational’ framing to provide a reason to act and a shared vocabulary of action for the movement.[44]

When these frames emerge and are widely shared within and among social movement organisations they are known as collective action frames.

Social movements have always used frames, but provocations to pay conscious attention to how they frame issues have their basis in cognitive linguist George Lakoff’s work on the underlying metaphors in political language. Lakoff pointed out that these metaphors evoke certain frames that in turn evoke problems that need to be met with corresponding solutions. He gives examples of metaphors circulating in US politics during the 1980s and 1990s, such as ‘government as a burden’ versus ‘government as common good’, both of which presuppose political positions on contentious issues. Whether a politician gives a speech about her government ‘providing relief for taxpayers’ (evoking the burden metaphor) or builds a case for ‘public investment in health/infrastructure/education’ (evoking the common good metaphor) depends on the overarching political response that the speaker seeks to evoke.[45]

While an organisation’s frame can evolve through challenges from within its own membership or by other members within a field of organisations, when it is attacked by a political opponent, ‘framing contests’ ensue, in which an opponent adopts an element of the movement’s frame to reframe and thereby direct debate on the issue towards the opponent’s position.[46] A recent example in Australia was the Morrison Coalition government’s Religious Discrimination Bill, which drew on anti-discrimination policies that had been embedded in legal frameworks during the second half of the 20th century to protect marginalised groups to reframe hegemonic religious groups as needing ‘protection’ from discrimination. The Bill was widely described by historians and sociologists of religion, as well as legal and civil liberties experts, as a response by the Coalition to pressure from conservative Christian groups to legitimate acts of discrimination against LGBTIQ+ people.[47] Legal advocacy groups further pointed out that the legislation would also potentially allow employers and employees in the faith-based care sector and religious schools to discriminate against and vilify people with disabilities and people of minority faiths as well as agnostic and atheist workers. By appropriating the language of civil rights enshrined in legal frameworks such as the Sex Discrimination Act, although ultimately unsuccessful, the campaign attempted to push through legislation that entrenched discrimination against a range of minorities and ‘others’.

Throughout the last three decades, as internet use has become widely adopted, social movements have increasingly used websites and social media to negotiate and disseminate collective action frames, rapidly communicate issues and mobilise people online. The internet has significantly reduced the costs of recruitment and lowered barriers to participation as traditional movement repertoires of contention, such as strikes, public meetings, street encounters, marches, rallies and mailed newsletters have become increasingly more burdensome in comparison to the low costs of engagement through internet-based apps such as Twitter, Instagram and Facebook. Debate exists within social movements themselves and social movement scholarship about whether internet-based movements can respond to political opportunities and engage in collective action framing to the same extent as face-to-face forms of organisation. Movements also increasingly question how open and democratic the ‘horizontal’ and inclusive membership structures associated with born-digital organisations are.[48]

While the internet has supplemented traditional activism to some extent, it has also provided virtual spaces for exchanges and engagement. The worldwide border closures and internal lockdowns associated with the COVID-19 pandemic from March 2020 onwards highlighted the value of such virtual spaces for sustaining social movement activity during a public health crisis. Many social movements drew on their existing digital networking expertise to quickly pivot to Zoom meetings and other platforms to discuss the emerging economic and social exclusions wrought by political responses (and lack thereof) to the pandemic.

Why do social movements cease to exist?

Just as groups and movements continue to form and act in response to their context, they also disappear if they are no longer relevant.

Scholars have described five conditions under which social movements can decline through interaction with the political opportunity structure:

- repression, whereby the state defines the movement as illegitimate and mobilises its own resources, whether legal, military, media-based or financial, overt or covert, to block or eliminate movement activity or organisations[49]

- co-optation, whereby the movement leaders may become vulnerable to joining their interests with movement targets rather than membership, either through offers of increased influence or direct monetary reward

- success, whereby the issue or claim that the movement has been making is achieved and its collective vehicles are no longer needed

- failure, whereby the organisation or broader movement ceases to share a collective action frame, either through internal divisions and splits, which can lead to ‘encapsulation’, in which the leadership becomes increasingly insular and there is a lack of renewal of members (possibilities that are inherent to exclusive membership organisations)

- formalisation (sometimes called bureaucratisation or mainstreaming), whereby the movement’s goals are adopted into the political system itself, and there is no longer an obvious social conflict between the movement and the system.[50]

It is possible that social movements undergo more than one of these forms of decline at once: for example, for a social movement might experience external repression leading to internal failure when stakes of contention are raised sharply, and organisational leaders and members can become isolated as a result. A recent example of this has happened in the anti-Extradition Bill (Anti-ELAB) movement in Hong Kong. Or a movement can experience success and formalisation at the same time, when the specific issue that it has been campaigning on is resolved, and there is widespread inclusion of movement actors within the decision-making apparatus, as in the mainstreaming of the feminist movement in the Australian state from the 1970s onwards. But many activists and movement scholars would argue, to return to the earlier discussion of state imperatives, that only those issues that directly align with acts that governments must perform for the sake of their own longevity and stability will be accommodated into the mainstream. It is possible that the radical and utopian parts of social movements that are unassimilable will always be excluded, and therefore act as a source of future renewal.

Conclusions

While the political sphere undergoes change from digital disruption and disaffection with democracy, social movements form an important conduit to ensure that ordinary people’s concerns and lived experiences are taken account of and reflected in policy. Theories of social movement formation and dynamics can help explain why some groups emerge and last, and some decline or are formalised.

An individual’s decision to join a social movement can be influenced by a variety of factors, but collective action is key to bringing about long-term change. Most importantly, social movements are the means by which more just alternatives to the status quo are imagined and made possible.

References

Adams, Rebecca G. and Koji Ueno (2008). Friendship and community organization. In Ram A. Cnaan and Carl Milofsky, eds. Handbook of community movements and local organizations, 193–210. New York: Springer.

Benford, Robert D., and David Snow (2000). Framing processes and social movements: an overview and assessment. Annual Review of Sociology 26: 611–39.

Carty, Victoria (2018). Social movements and new technology. New York: Routledge.

Christiansen, Jonathan (2009). Social movements and collective behavior: four stages of social movements. EBSCO Research Starter 1: 1–7.

Diani, Mario (1992). The concept of social movement. Sociological Review 40(1): 1–25.

Dryzek, John S. (2002). Including Australia: a democratic history. In Geoffrey Brennan and Francis G. Castles, eds. Australia reshaped: 200 years of institutional transformation, 115–47. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Earl, Jennifer (2003). Tanks, tear gas and taxes: toward a theory of movement repression. Sociological Theory 21(1): 44–68.

——, Thomas V. Maher and Jennifer Pan (2022). The digital repression of social movements, protest, and activism: a synthetic review. Science Advances 8(10).

Eyerman, Ron (2005). How social movements move: emotions and social movements. In Helena Flam and Debra King eds. Emotions and social movements, 41–56. London: Routledge.

First Mardi Gras Inc. (2022). The first Mardi Gras. https://www.78ers.org.au/what-happened-at-the-first-mardi-gras

Fominaya, Cristina Flesher (2010). Collective identity in social movements: central concepts and debates. Sociology Compass 4(6): 393–404.

Gitlin, Todd (2003). The whole world is watching: mass media in the making and unmaking of the new left. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Gregoire, Paul (2018). Religious exemption laws: an interview with Professor Marion Maddox. Sydney Criminal Lawyers, 18 January. https://www.sydneycriminallawyers.com.au/blog/religious-exemption-laws-an-interview-with-professor-marion-maddox/

Guigni, Marco (2009). Political Opportunities: From Tilly to Tilly. Swiss Political Science Review 15(2): 361-368.

Kitzinger, Jenny (2007). Framing and frame analysis. In Eoin Devereux, ed. Media studies: key issues and debates, 134–61. Los Angeles: SAGE.

Lakoff, George (2014). Framing 101: How to take back public discourse. Don’t think of an elephant!: know your values and frame the debate: the essential guide for progressives, 1–32. White River Junction, VT: Chelsea Green.

Liveris, Tass (2022). The good and the bad of the religious discrimination bill: the Law Council’s verdict. Law Council of Australia, 9 February. https://www.lawcouncil.asn.au/media/news/the-good-and-the-bad-of-the-religious-discrimination-bill-the-law-councils-verdict

Maddison, Sarah and Sean Scalmer (2005). Activist wisdom: Practical knowledge and creative tension in social movements. Kensington: University of NSW Press.

McAdam, Doug, John McCarthy and Mayer N. Zald (1996). Introduction: opportunities, mobilizing structures, and framing processes – toward a synthetic, comparative perspective on social movements. In Doug McAdam, John McCarthy and Mayer N. Zald, eds. Comparative perspectives on social movements: political opportunity structures, mobilizing structures, and cultural framings, 1–20. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

McAlevey, Jane (2016). No shortcuts: organizing for power in the new gilded age. New York: Oxford University Press.

Mitchell, Timothy (1990). Everyday metaphors of power. Theory and Society 19(5): 545–77.

Moyer, Bill (1987). The movement action plan: a strategic framework describing the eight stages of successful social movements. History Is A Weapon. https://bit.ly/3u5zFZp

Olson, Mancur (2022 [1965]). The logic of collective action: public goods and the theory of groups. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Parkes-Hupton, Heath (2022). NSW parliament passes new laws bringing harsher penalties on protesters. ABC News, 1 April. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2022-04-01/nsw-new-protest-laws-target-major-economic-disruption/100960746

Public Interest Advocacy Centre (PIAC) (2022). Extremely disappointing reports fail to address fundamental problems in Religious Discrimination Bill. PIAC: media releases, 4 February. https://piac.asn.au/2022/02/04/extremely-disappointing-reports-fail-to-address-fundamental-problems-in-religious-discrimination-bill/

Ricketts, Aidan (2012). Public sector activism: how to change the law and influence government policy. Activists’ handbook, 106–129. London: Zed Books.

Smith, Rodney, and Anika Gauja (2019). Chapter 3: Who can vote. State Library of NSW. https://legalanswers.sl.nsw.gov.au/hot-topics-voting-and-elections/who-can-vote

Snow, David A., Sarah A. Soule and Hanspeter Kriesi (2004). Mapping the terrain. In David A. Snow, Sarah A. Soule and Hanspeter Kriesi, eds. The Blackwell companion to social movements, 3–16. Oxford: Blackwell.

Suh, Doowon (2001). How Do Political Opportunities Matter for Social Movements?: Political Opportunity, Misframing, Pseudosuccess, and Pseudofailure. The Sociological Quarterly 42(3): 437-460.

Tarrow, Sidney G. (2011). Power in movement: social movements and contentious politics. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Taylor, Marilyn (2008). The nature of community organizing: social capital and community leadership. In Ram A. Cnaan and Carl Milofsky, eds. Handbook of community movements and local organizations, 329–45. New York: Springer.

Taylor, Verta A., and Nella Van Dyke (2004). ‘Get up, stand up’: tactical repertoires of social movements. In David A. Snow, Sarah A. Soule and Hanspeter Kriesi, eds. The Blackwell companion to social movements, 262–93. Oxford: Blackwell.

Thompson, Edward Palmer (1971). Moral economy of the English crowd in the eighteenth century. Past & Present 50: 76–136.

Tilly, Charles (1978). From Mobilisation to Revolution. Reading: Addison-Wesley.

Tilly, Charles (1999). From interactions to outcomes in social movements. In Marco Giugni, Doug McAdam and Charles Tilly, eds. How social movements matter: theoretical and comparative studies on the consequences of social movements. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

Tufecki, Zeynab (2017). Twitter and tear gas: the power and fragility of networked protest. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Van Dyke, Nella, Sarah A. Soule and Verta A. Taylor (2004). The targets of social movements: beyond a focus on the state. Research in social movements, conflicts and change 25: 27–51.

Zald, Mayer N., and Roberta Ash (1966). Social movement organizations: growth, decay and change. Social Forces 44: 327–41.

About the author

Dr Justine Lloyd is an urban and cultural sociologist in the discipline of sociology at the School of Social Sciences, Macquarie University. She teaches courses on gender and power, activism, and social change and social theory. She researches urban social movements and how they use place-based narratives and media to promote social justice.

- Lloyd, Justine (2024). Social movements. In Nicholas Barry, Alan Fenna, Zareh Ghazarian, Yvonne Haigh and Diana Perche, eds. Australian politics and policy: 2024. Sydney: Sydney University Press. DOI: 10.30722/sup.9781743329542. ↵

- This Chapter includes text from “Pressure groups and social movements” by Moira Byrne (2021), available under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial license Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial Share Alike 4.0 International License. ↵

- Tarrow 2011, 6. ↵

- Tilly 1999, 257. ↵

- Diani 1992. ↵

- Van Dyke, Soule and Taylor 2004, 29. ↵

- Snow, Soule and Kriesi 2004, 11. ↵

- Dryzek 2002. ↵

- Castles in Dryzek 2002, 123. ↵

- Smith and Gauja 2019. ↵

- Dryzek 2002, 116. ↵

- Dryzek 2002, 131. ↵

- Moyer defines ‘trigger events’ as ‘shocking incident[s] that dramatically [reveal] a critical social problem to the general public in a new and vivid way, such as the arrest of Rosa Parks for refusing to move to the back of a Montgomery bus in 1955 or NATO’s 1979 announcement to deploy American Cruise and Pershing 2 nuclear weapons in Europe. Trigger events can be deliberate acts by individuals, governments, or the opponents, or they can be accidents.’ Moyer 1987, 2. ↵

- First Mardi Gras Inc. 2022. ↵

- Fominaya 2010. ↵

- Olson 2002 [1965]. ↵

- Maddison and Scalmer 2005, 23. ↵

- Thompson 1971. ↵

- Mitchell 1990, 547. See Thompson 1971, 79. ↵

- Taylor and Van Dyke 2004, 263. ↵

- Snow, Soule and Kriesi 2004, 7. ↵

- Tarrow 2011, 42–7. ↵

- Tilly 1999, 45–6. ↵

- Tilly 1999, 261. ↵

- Tilly 1999, 261. ↵

- Tarrow 2011, 26. ↵

- Tarrow 2011, 33. ↵

- Suh 2001, 439. ↵

- Tilly 1978, chapter 4; Guigni 2009, 361; McAdam, McCarthy and Zald 1996, 10; Tarrow 2011, 27. ↵

- Ricketts 2012. ↵

- Parkes-Hupton 2022. ↵

- McAdam, McCarthy and Zald 1996, 3, 18. ↵

- Zald and Ash 1966, 330–1; Adams and Ueno 2008. ↵

- Tilly 1999, 264–6. ↵

- McAdam, McCarthy and Zald 1996, 3, 18. ↵

- Zald and Ash 1966, 330–1. ↵

- Zald and Ash 1966, 330–1. ↵

- Taylor 2008, 336. ↵

- Taylor 2008, 336. ↵

- McAlevey 2016, 9–10. ↵

- Gitlin 2003, 6. ↵

- Kitzinger 2007, 137. ↵

- Eyerman 2005, 45–6. ↵

- Benford and Snow 2000, 615–18. ↵

- Lakoff 2004. ↵

- Benford and Snow 2000. ↵

- Gregoire 2018. ↵

- Tufecki 2017; Carty 2018. ↵

- Earl 2003; Earl, Maher and Pan 2022. ↵

- Christiansen 2009, 4. ↵