25 Political leadership

Michael de Percy and Stewart Jackson

Key terms/names

attribution theory, charismatic leadership, contingency theory, irrelevance theory, personality cult, political leadership, situational theory, transformational leadership, transactional leadership

Political leadership is inherently fragile.[1] Leadership literature tends to focus on leaders from business, the military or the public service.[2] While leadership is now a part of university management courses, its study originates with religion and politics, and has a significant tradition in the discipline of political science.

The oldest accounts of leadership include The epic of Gilgamesh in ancient Mesopotamia, the Old Testament and other religious texts attributed to the Abrahamic prophets, Homer’s The Iliad and The Odyssey, and the accounts of Alexander the Great. The spirit of leadership at the heart of religion and politics was examined systematically by the originator of the study of leadership, Thomas Carlyle (1795–1881) in his book On heroes, hero-worship, and the heroic in history (1841). Carlyle’s legacy is encapsulated in the regrettably named and antiquated ‘Great Man’ theory of leadership – the idea that leadership is about ‘great’ people and their personal influence on history. According to this idea, if students could identify with and emulate great leaders’ traits, they could then learn to become effective leaders. This was certainly the basis of the leadership treatises of Erasmus and Machiavelli on whether – and how – a Christian prince should be feared or loved.

The presupposition that leadership is something that can be learnt as opposed to being limited by ‘birthright’ challenges not only the likes of outliers and revolutionaries such as Spartacus (the Thracian gladiator and revolutionary), but also Jesus (a carpenter) and Mohammed (an illiterate merchant). Importantly, these early leaders democratised leadership in that even those of humble beginnings could inspire millions of followers not only in their own time but also through the ages. The example of the prophets as leaders is not only idealistic but has become the norm in liberal democracies, particularly over the last two and a half centuries, where leadership has been increasingly based on merit and public perception rather than by inherited birthright.

Despite the many decades of theoretical development of leadership, leadership education today is typically focused on organisational leadership within the context of capitalist business organisations, where leaders focus on achieving an appropriate return for shareholders. Where the interests of shareholders coincide with the concerns of citizens or consumers, this may provide opportunities for some form of political leadership by business elites, as exemplified by Qantas CEO Alan Joyce’s support for same-sex marriage in Australia.

Leadership in the private sector involves a non-democratic process of leadership selection that is not subjected to the ongoing whims of what we might call the polis. While leadership has been identified as an important variable in the achievement of desired outcomes in organisations, political leadership encompasses dimensions that include not only particular leaders’ abilities to solve policy problems, but also their style of communication and engagement, and hence the perceived level of empathy with their constituents.

The level of emphasis placed on outcomes versus perceptions of political leadership cannot be measured by hard and fast rules about performance. Indeed, it is often the case that the logic of what may appear to be rational is not reflected in electoral outcomes, suggesting that political leadership requires more than rationalist assumptions about preferred societal goals. Ironically, such disagreement between logic and practice echoes what one might find on #AusPol on Twitter, where Australia appears to suffer through endless leadership crises, no matter who the leader may be but entirely in accordance with the views of the ‘gang’ the commentators belong to (a topic we return to later).

There are many lessons to be learnt from the study of historical and contemporary political leaders. This chapter explores political leadership in theory and in practice, and examines the development of our understanding of political leadership through a historical lens. The chapter also adopts a unique approach to providing students with the opportunity to develop their own understanding of leadership while learning more about political leadership per se. Rather than espouse a particular view of political leadership (which would reflect the views of the relevant ‘gang’), the chapter provides politics students with contemporary knowledge of leadership from the research literature, alongside the practice of political leadership from ancient times to the present day.

Why learn about leadership? What is leadership?

Learning about leadership begins with a philosophy of leadership education.

If we believe that leaders are born and not made, then it is pointless to learn how to become an effective leader. This is reflected in French Emperor Napoléon Bonaparte’s self-serving observation that ‘Great men [sic] are meteors, who, by their burning, light the world’.[3] ‘Birthright’ theories view leadership as a set of characteristics exhibited by great leaders.

Birthright in leadership was shunned by Plato’s (380 BCE)[4] republic, where the best system of government came from selecting ‘philosophers’ for political rule. But until the democratic election of Athens’ famous leader, Pericles,[5] birthright and family politics determined political leadership in Ancient Greece. Of course, democracy presupposes equality, a condition where anyone is considered not only eligible, but capable, of ruling should they be selected to do so by their peers. But democracy, especially its modern variant that incorporates universal suffrage, assumes that almost anyone can learn to become a leader. This includes women, who for much of human history have been sidelined by male-dominated ideas of leadership (including in the name of the first leadership ‘theory’). But what is leadership?

Birthright theories ignore the leaders’ relationships with their followers, the tasks at hand, the organisation the leader is supported by, and the strategic environment that such leadership occurs in.[6] Modern perspectives begin with the premise that leadership is about motivating followers towards some vision, providing solutions in times of crisis, or otherwise getting people to do what they would otherwise not do. The key point, however, is that effective leadership requires followers to act voluntarily – a point not lost on stories such as the sacrifice of the 300 Spartans at the battle of Thermopylae.[7] Further, leaders must achieve something that makes circumstances better for followers than before their leadership began.

Defining political leadership presents a challenge because of the diversity of places where leadership can occur.

Leaders do not necessarily need to hold formal positions to be regarded as influential and effective; political leaders may not necessarily be politicians. They may include leaders of informal bodies, like social movements, such as Charles Frederick (Fred) Maynard (1879–1946) an important Aboriginal activist whose work led to the creation of the Australian Aboriginal Progressive Association in the 1920s. Alternatively, leaders do commonly hold roles in formal organisations, like political parties, business leaders, and so on. Some bridge both worlds, like the social reformer Edith Cowan (1861–1932) who became the first woman elected to parliament in Australia in 1921.

Leaders of social movements or business leaders are not subjected to the same scrutiny as political leaders and are often responsible for a narrower set of outcomes that contribute indirectly to the common good. To be sure, legal and ethical behaviour is important, but business leaders, for example, are primarily focused on profit-seeking, which may include socially responsible behaviours designed to align the corporation’s values with extant societal values. Indeed, it is generally accepted that corporate social responsibility is not incommensurate with improving market performance.[8]

Political leaders, on the other hand, are ideally responsible for protecting the public interest and contributing to the common good by creating, maintaining, or contributing to society through the institutions of the state that establish the rules for businesses and citizens. Political leadership also occurs within particular cultural and social contexts, ranging from idiosyncratic behaviours that reflect cultural norms, to common ideological positions that may include preferences for ways of managing issues of equality and equity such as education and healthcare, and the extent of competition and government intervention in the market.

Theorising political leadership

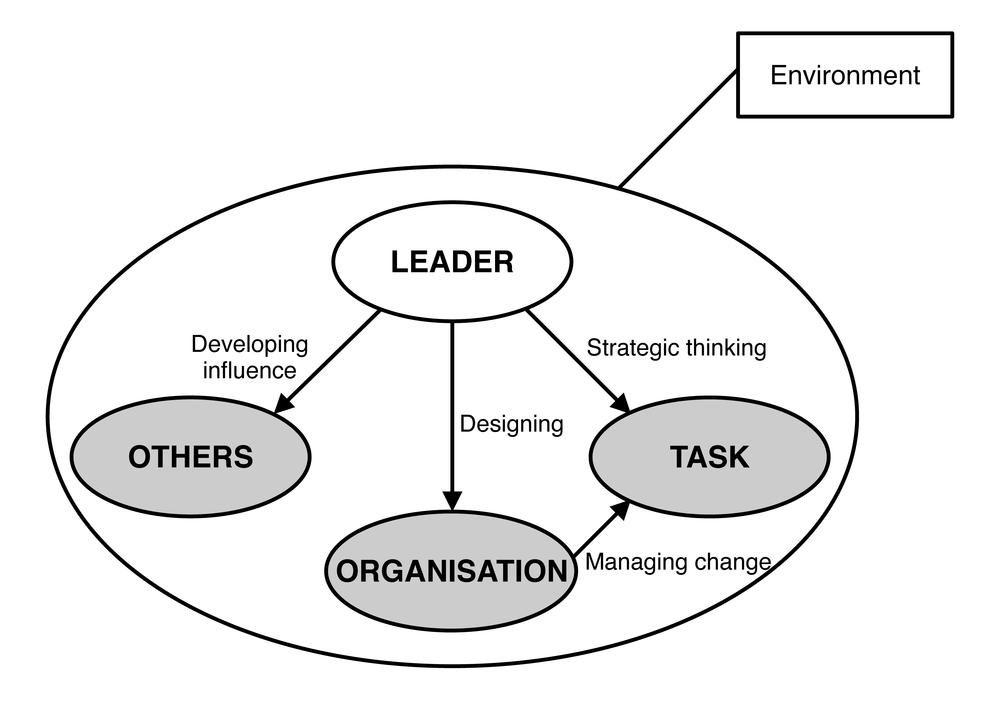

Theories of leadership reflect the historical development of research on the topic.[9] Clawson’s diamond model of leadership outlines the various elements of leadership study, beginning with the self, and moving through the followers, the task, the organisation, and the strategic context (Fig. 1).[10] The early concepts of trait theory inform thinking about the leader (the self), where examples of effective leadership are observed, and their traits and characteristics are noted. The student of leadership can then attempt to emulate the traits of great leaders. The problem with trait theory is that there is no exhaustive list of traits, and no guarantee that a person who possesses these traits can be an effective leader. Focusing on the leader as an individual ignores one of the most important elements of leadership – the relationship between the leader and the followers.

The concept of charismatic leadership provides a first glimpse at the relationship between the leader and followers, in that charisma is not something that one can necessarily develop in isolation. Charisma is often referred to as a special relationship between the leader and followers where followers see a certain ‘attractiveness’ in the leader. Charismatic leaders vary, ranging from ‘warm’ to ‘cold’ in their relationships with their followers. People ‘warmed’ towards political leaders such as the late Bob Hawke, who had a sense of working-class charm and larrikinism that reflected Australian society at the time. Former US President Donald Trump brought to the USA public the promise of entrepreneurial flair and a return to national greatness, with people either ‘warming’ towards Trump or being eerily ‘chilled’ by his unconventional antics on social media. An interesting consequence of charismatic leadership is that followers often divide along lines of either loving or loathing the leader.[11] In the case of Adolf Hitler, seen as an archetypal user of charisma to win over support, charismatic leaders can fall victim to the ‘allure of grandiosity’ or, by developing unquestioning loyalty, encourage followers to engage in unethical or even evil acts if asked to do so.

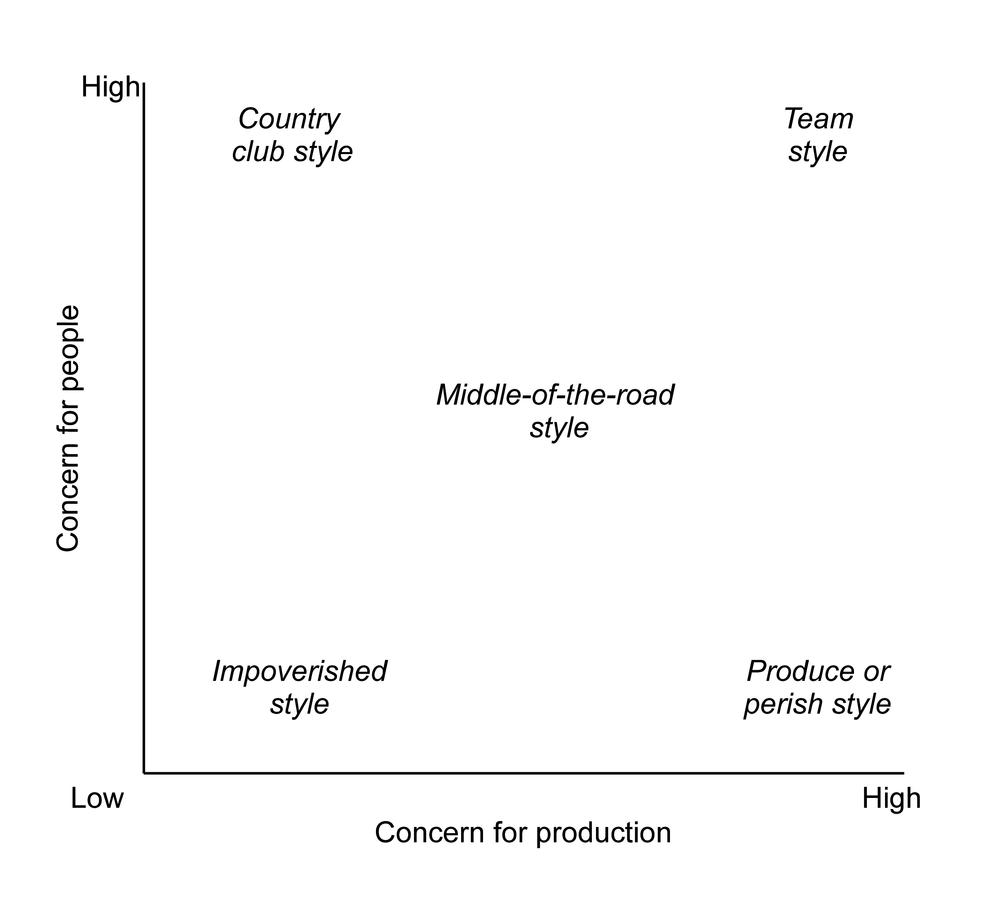

Leadership behaviours towards followers can be observed and, much like traits, emulated by potential leaders. Typically, leadership behaviours consider the degree of task versus relationship focus and are often portrayed as a matrix or grid.[12] Leadership behaviours may also vary along ideological or political party lines. For example, Labor Prime Minister Bob Hawke used a consensus-building style of leadership, in part supported by the collectivist culture of the trade union movement;[13] whereas Liberal Prime Minister Tony Abbott was infamous for his ‘captain’s calls’ where he made decisions as the leader without consulting his colleagues, ultimately leading to his downfall.[14]

Situational and contingency leadership theories incorporate the traits of the leader, the relationship with the followers, and the task at hand. The basic premise of the situational leadership model is that the leader can change their style to suit the situation. In the context of political leadership, situational leadership might be considered a form of crisis leadership, that may or may not be within the jurisdiction of the leader, suggesting that the role of political leaders can often be symbolic rather than practical. Recent examples include the 2019 bushfires in Australia, where Prime Minister Scott Morrison was called to account by the media for emergency management activities which are not a responsibility of the national government, and the ongoing response to the COVID-19 pandemic, which is arguably beyond the capabilities of one individual. Yet the situation called into question the Prime Minister’s suitability to act as the nation’s leader, stressing the importance of the situation in the leadership equation.

There are two key theoretical propositions in situational versus contingency leadership. First, the Hersey and Blanchard situational leadership model suggests that leaders can adapt their leadership style to suit the ‘readiness’ (characteristics, experience, attitude, socio-demographic background and so on) of the followers and the requirements of the task at hand.[15] This view assumes that effective leaders can change themselves rapidly to suit a given situation. Second, Fiedler’s contingency theory of leadership suggests that leaders are predominantly either task or relationship focused, and their default style is difficult if not impossible to change.[16] The effects of these two propositions about leadership are that leaders can either change their style to suit the situation, or the choice of leader is contingent upon the situation. Alternatively, the leader may try to change the situation to suit their leadership style.

While there are numerous other theories of leadership, for the purposes of this chapter the last group of theories relate to the ‘socio-cognitive’ aspects of leadership. Put simply, leadership effectiveness is attributed to the leader by the followers; or otherwise, leadership ‘is in the eye of the beholder’.

Two interesting ideas about the importance of leadership emerge from these socio-cognitive aspects. First, there are other parts of the policy environment – such as political institutions, political parties, laws, rules, behavioural norms, and so on – that make leadership less relevant than is assumed.[17] For example, whether a prime minister has any real impact on societal outcomes assumes a level of simplicity that is belied by the practice of politics and policy which typically results in ‘satisficing’ needs and wants as opposed to providing the best possible response to a policy problem.[18] Second, we attribute to the leader collective successes that could not possibly be the result of an individual’s actions. Much as political leadership in Australia has been individualised (or ‘presidentialised’[19]), Australia remains a country marked by Cabinet government with power spread across its federation.

These approaches, which may be referred to as ‘leader irrelevance theory’ and ‘leader attribution theory’ respectively,[20] say much about the importance or otherwise of leadership. Political leadership, then, must consider a broader range of issues including the resilience and capacities of political institutions, cultural norms,[21] and the symbolic functions expected of political leaders that may or may not be directly related to political outcomes.

An interesting addition to the socio-cognitive understanding of leadership stems from the work of James MacGregor Burns.[22] Burns conducted biographical studies of political leaders and two key theories emerge from his work: transformational leadership and transactional leadership.

Transformational leadership, typically stemming from revolutionary leaders, has been adopted by business scholars to understand the role of leadership in pursuing ongoing organisational renewal in the ever-changing external business environment. For most political leaders in Western liberal democracies, however, the heavily institutionalised nature of the political environment, predicated by regular, peaceful ‘revolutions’ at the ballot box, make transformational leadership difficult to achieve without disrupting the entire political system.[23] Most leaders in liberal democracies tend to practice transactional leadership, where leaders and followers exchange ‘gratifications in a political marketplace’, and opinion leadership is key.[24]

There is also a temporal dimension to political leadership where given leaders may suit particular times in history or where a particular type of leader has the characteristics regarded by citizens as necessary to deal with contemporaneous issues. The leader is a person of their times and ideas.

The next section looks to the followers of political leaders, and the importance and challenges of having a core group of supporters to ensure sufficient support for a leader.

Leader of ‘the gang’?

A major challenge for political leaders in adversarial, two-party, democratic systems is in keeping their party followers on side while at the same time attracting enough of the ‘swinging voters’ to form a majority government. Political leaders in liberal democracies, whether parliamentary or presidential, must gain and maintain the support of the party faithful if they are to remain effective political leaders. Australia has experienced disrupted political leadership in both the Labor and Coalition ranks in recent years where leaders were unable to keep their party members on side. Interestingly, political parties have not moved far from their original formation in what might ordinarily be called ‘cliques’ – small groups of political insiders consisting of notables and nobles who supported a particular leader – that would later develop into organised groups operating under a label with the purpose of converting political outsiders into political followers.[25] While electoral competition between organised political parties is a normal part of the function of liberal democracies, the leader’s relationship with the followers resembles its earlier arrangement as a clique, but with some important qualifying points.

Barack Obama is often lauded as an inspirational leader and, as the first African-American president of the USA, an example of liberal democracy’s equality of opportunity facilitating social mobility. Followers flocked to Obama’s charisma and message of ‘hope’, attracting some of the largest political crowds in USA history, and even attracting a crowd of some 200,000 people in Germany.[26] But despite his global popularity, the award of a Nobel Peace Prize, and the vastly symbolic nature of his presidency, Obama achieved only one major (yet fragile) legislative achievement in the Affordable Care Act (known colloquially as Obamacare) that is yet to achieve what it set out to do (increase Americans’ access to healthcare services) while nearly doubling in cost.[27] One of the most interesting effects of Obama’s two-term presidency is that, despite his popularity with voters, he failed to ‘speak’ to the party faithful. Developed in collaboration with experts rather than civil service bureaucrats,[28] Obamacare not only came under attack from Obama’s successor, Trump, but also isolated the Democratic Party faithful.[29] The end result was that despite Obama’s second term as president, the Republicans were able to control Congress, and ultimately limit Obama’s ability to implement lasting reforms that were soon to be deliberately targeted by his Republican successor.[30] This leads to some interesting observations about the primal origins of political parties that remain pervasive in the practice of political leadership.

Coalition Opposition Leader John Hewson’s attempt to introduce a value-added tax in the early 1990s demonstrated the political risk involved in posing technically detailed reforms to a sceptical public. Paul Keating, who had been in favour of this type of tax on consumption from the early 1980s (and had been criticised for his inability to implement it), used an anti-Goods and Services Tax (GST) campaign to devastating effect against Hewson at the 1993 election.[31] The GST debate highlights how difficult it is to introduce major reforms (that are generally agreed upon as necessary by policy makers) when scare campaigns present easy opportunities to delay implementation longer than necessary. Further, technical competence (Dr Hewson was a trained economist) is not sufficient to lead major reforms as a politician. The ability to ‘bring the people with you’ and to collaborate, negotiate, and compromise appear to be the most important skills for political leaders. Initially, then Prime Minister John Howard went back on his ‘non-core promise’ to ‘never ever’ introduce a consumption tax. However, following an election which focused on his proposed GST (which was implemented on 1 July 2000), Howard had secured the backing of the states and Meg Lees, leader of the Australian Democrats, to (partially) introduce the reforms.[32] Lees lost her leadership of the Democrats because of her decision to support the GST. Further, and despite Hewson and Keating supporting a consumption tax in theory, it was Howard’s political leadership that facilitated the introduction of a major reform that is nowadays rarely considered to be controversial.

Davis’ depiction of Australian prime ministers as ‘leader[s] of the gang’[33] was an apt description for understanding the series of ‘knifings’[34] that took place with six Labor and Coalition prime ministers changing places in the same number of years that John Howard, the second longest serving prime minister in Australian history, had occupied the role. Davis referred to the ‘terrible but predictable rhythm to these regular assassinations’[35] of prime ministers as an inevitable event unfolding before the public eye, only to be ended by the unlikely leadership of Scott Morrison who has remained in power since the 2018 federal election, despite the bushfire debacle and his tenuous Trumpism in the early stages of the pandemic. Morrison’s remarkable resilience and ability to reset have not been lost on voters, with most opinion polls supporting his leadership, although rallying behind the leader during a time of crisis tends to favour the incumbent. Nonetheless, politics tends to defy the logic of prediction, so there is no guarantee that the level of support for Morrison gained during a crisis will remain once policies addressing the pandemic have run their course.

Drawing on socio-cognitive aspects, however, measuring leadership success in politics depends on how leadership is viewed. Political leaders play an important symbolic role in inspiring others to act on important political and social issues and for creating a vision for a better future. Of course, much of these important sentiments are not necessarily reflected in policy outcomes, and even inspirational political leaders can be perceived as empathetic while ineffective in a policy-outcome context. Jacinda Ardern, for example, has been described as a ‘show pony’ who uses her empathy to appeal to the media.[36] Once held up as an example of an empathetic global leader, amid a lack of achievement of policy outcomes, New Zealand’s parliament has been referred to as an ‘elephant’s graveyard of internet memes’ with Ardern calling the opposition leader a ‘Karen’ and a member of the Greens responding to a heckler with ‘OK boomer’.[37]

On the other hand, Australia’s first female prime minister, Julia Gillard, famous for her symbolically important ‘misogyny speech’, was concerned that those few moments of parliamentary footage overshadowed the National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS), one of the most important social justice reforms in Australian political history.[38] Such is the lot of a political leader.

In three years as Australia’s first female prime minister, Julia Gillard’s most important policy legacy is arguably the establishment of the National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS). After a controversial leadership challenge that ousted Kevin Rudd as Prime Minister, and an election resulting in the first hung parliament since 1940, Gillard had to draw on her considerable negotiation skills to establish government and then to implement the NDIS in such a short timeframe. First, she had to negotiate a minority government with Greens’ leader Adam Bandt and three independent MPs. Second, she had to negotiate with state premiers and territory chief ministers to secure agreement to implement the NDIS. Policy making is often considered easier than implementation. In 2011, the Productivity Commission reported on Australia’s disability care and support services, a process that began with a 2007 Senate Standing Committee inquiry recommending major reform to the sector. Numerous negotiations through the Council of Australian Governments (COAG) and a few years later, the reform framework was agreed and implemented rather quickly, given an otherwise ‘lack of appetite for reform’ that characterised the leadership instability of the period.[39]

Contemporary leadership issues

Political leadership in liberal democracies has become polarised and is often fought out in an equally polarised media environment. The COVID-19 pandemic created a global economic crisis not seen since the Great Depression of the 1930s,[40] and has called into question many stereotypical notions of political leadership. These stereotypical notions encompass issues of gender, populism, and ideology during what is the most significant health and economic crisis in living memory. In the past we might have discussed leadership in political crises by comparing the approaches of former New York Mayor Rudy Giuliani in the aftermath of the 9/11 terrorist attacks on the World Trade Center with the strength and confidence of former Chief of the Australian Defence Force and later Governor General, General Sir Peter Cosgrove, during the transition to East Timor’s independence, or former UK Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher overcoming the gender ‘glass-ceiling’ in Western political leadership. But such comparisons reflect the historical and traditional gendered roles in the private versus the public spheres and do not stand the test of time. The pandemic, for instance, ‘has provided unusual opportunities for women political leaders to display forms of protective femininity’, based on traditional roles for mothers for hygiene and caring for the sick in the private sphere.[41] During the pandemic, the traditional ‘head of household and warrior defender’ role, or ‘protective masculinity’, has, in many cases, failed to win the hearts and minds of voters and delivered opportunities for political leadership for women previously unheard of.[42]

A brief glance at contemporary prime ministers in Australasia reveals much of the changing nature of political leadership in times of crisis. New Zealand’s prime minister, Jacinda Ardern, following the Christchurch mosque shootings in 2019, became a global celebrity after she wore a hijab to the memorial service for those killed by an Australian right-wing terrorist.[43] Soon after, Ardern appeared on the front page of Time magazine, referred to as a ‘millennial marvel with progressive goals and courage under fire’.[44] Media plays an interesting role in modern political leadership, and it is not unusual for political leaders to be compared with leaders from other countries. During Ardern’s popularity, for example, there were calls for her to become Australia’s prime minister following Scott Morrison being castigated for being on holiday in Hawai‘i during the devastating Australian bushfires in late 2019. Upon his return, Morrison’s attempt to console victims of the fire turned into a public relations catastrophe when several of the victims refused to shake his hand while others heckled and even verbally abused him on national television.

A major issue that public opinion of leaders ignores, of course, is that political leadership does not occur in a political vacuum. Western liberal democracies tend to be so heavily institutionalised to the extent that ‘the wider political environment is too intrusive, hostile, and intractable to permit indulgence in utopianism’.[45] Indeed, history is littered with the likes of Hawke’s claim that ‘by 1990, no Australian child will be living in poverty’.[46] Historically, authoritarian leaders such as Mao Zedong in China have been able to make decisions that largely transformed societies, but at a morally questionable cost. Yet during times of crisis, leaders in liberal democracies are expected to ditch the institutions that make liberal democracy work, while at the same time deliver solutions to problems that no individual leader can possibly deliver. To borrow from Burns, a leader who crushes all opposition is no longer a leader but a tyrant,[47] bringing us back to our earlier definition of leadership that requires followers to do voluntarily what they otherwise wouldn’t do without the leader’s prompting.

Before COVID-19, the rise of populism in the USA and the UK (and to a limited extent in Australia), appeared to be the latest trend in political leadership. Ideas about ‘neoliberalism’, a term typically used as a critique of the global trend toward market liberalisation over the last three decades,[48] were being challenged by a return to protectionist policies. This occurred in the USA as a reaction to China’s growing economic power under the leadership of then President Donald Trump, and in the UK in the form of Brexit.

Globalisation,[49] the so-called inevitable driving force behind market liberalisation amid economic reforms by former US President Ronald Reagan and former UK Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher, would seem to be under attack from a new wave of populist nationalism. In an interesting turn, the conservative parties in the USA, UK, and Australia have changed focus on an inevitable globalisation, to globalism, where nation-states choose the nature of their global interaction.[50]

Recent speeches by Chinese President Xi Jinping[51] and Russian President Vladimir Putin[52] reflect growing global confidence amid the decline of USA global power. Arguably, the leadership styles adopted by Xi and Putin would be difficult to adopt in liberal democracies given the adversarial nature of Western two-party political systems. Populism, however, a term that loosely describes the approach where a charismatic leader claims to speak in the interests of ‘the people’ and against an ‘established elite’, has emerged as a reaction to the changing geopolitical situation.[53] Deployed in an ideologically neutral context by right and left-wing politicians – think here of Hugo Chavez in Venezuela and Jair Bolsonaro in Brazil, or the Donald Trump and Bernie Sanders campaigns in the 2016 US Presidential campaign – populism challenges the rules-based world order and fuels nationalist foreign policy agendas that amount to a new Western leadership trend with traditional alliances being reinforced as vaccine-nationalism has increased.

While not quite a neo-Cold War world order, security alliances are challenging trading partnerships, particularly Australia’s relationship with China, and the ongoing pandemic has presented opportunities for China and Russia (along with Australia) to engage in an emerging notion of ‘vaccine diplomacy’. Amid this changing global environment, political leaders are being held accountable by the perennial ‘court of public opinion’[54] while bureaucrats such as state and federal chief health officers are finding their positions politicised and their expertise challenged by populist sentiment. Political leadership is under immense pressure to provide for the endless needs, wants, and desires of the polis. At a time when our understanding of leadership might arguably have matured since Carlyle’s conception of the ‘great men’ [sic] of history, an impartial observer today might justly claim that our collective fascination with the personality cult – ‘of devils as well as heroes’ – indicates we have not come that far at all.[55]

The future of political leadership: stewardship?

The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic (and likely future pandemics) will leave lasting changes to how we live and work in Australia. Already, the latest intergenerational report suggests that Australia’s population and economic growth are expected to slow down for the foreseeable future.[56] An immediate priority for political leadership, then, is surely to provide for the prosperity of future generations.

Such future-focused leadership that spans generations is referred to as stewardship. Like leadership, the concept of stewardship[57] has ancient antecedents, with some of the first references to human beings taking active responsibility for the natural environment even mentioned in the earliest parts of the Old Testament dating back to before 500 BCE (for example, in Genesis 2:15). Notions of stewardship over the natural environment (collective commons, rivers, freshwater springs, flora and fauna, and so on) were commonplace in many Western (and some non-Western) societies until the industrial revolution (1780s) but then re-emerged as the ‘national trust’ conservation movement in the late 19th century, with Australia’s Royal National Park established in 1879 as one of the earliest in the world.

Stewardship historically implied the exercise of some intergenerational custodianship and collective responsibility for an entity or a body charged with such responsibility. It emphasised the need for the management of a natural resource for the collective interests of the community or for the sustainability of the resource itself, rather than a preoccupation with the more self-centred management of personal assets through the ownership of natural resources. Stewardship also involves making long-term decisions including devising preparatory plans for the future.[58] In essence, accepting a stewardship responsibility involves the willingness to be held accountable collectively or organisationally for sustainable outcomes across generations.

Such lofty ideals are difficult to achieve in three-to-four-year electoral cycles, and the absence of a clear policy for reducing carbon emissions in Australia has now been overshadowed by the spectre of pandemic-created national debt for the foreseeable future. Whether political leadership in liberal democracies and its incremental approach to reform can cope with rapidly changing global circumstances remains to be seen. But if history proves anything, it is that time thwarts the best of all intentions.

References

Australian Department of the Treasury (Treasury) (2021). 2021 intergenerational report: Australia over the next 40 years. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia. https://treasury.gov.au/publication/2021-intergenerational-report

Blake, Robert R., Jane S. Mouton and Alvin C. Bidwell. (1962). Managerial grid. Advanced Management – Office Executive 1(9): 12–15.

Boese, Vanessa A., Amanda B. Edgell, Sebastian Hellmeier, Seraphine F. Maerz and Staffan I. Lindberg (2021). How democracies prevail: democratic resilience as a two-stage process. Democratization 28(5): 885–907. https://doi.org/10.1080/13510347.2021.1891413

Bonaparte, Napoleon (2010 [1916]). Napoleon in his own words from the French of Jules Bertaut. Charleston, SC: Nabu Press.

Burns, James M. (2012 [1978]). Leadership. New York: Open Road Media.

Carlyle, Thomas (1841). On heroes, hero-worship, and the heroic in history. London: James Fraser.

Clawson, James (2012). Level three leadership: getting below the surface. St Leonards, NSW: Pearson.

Confucius (1995 [c. 206 BCE]). The analects. Mineola, NY: Dover.

Davis, Glyn (2011). Leader of the gang: how political parties choose numero uno. Griffith Review, 1–29.

De Percy, Michael A. (Host), and Michelle Grattan (Speaker). (2017). On bipartisanship, reform fall guys, Asian century, and infrastructure with Michelle Grattan. Le Flaneur Politique [podcast]. Michael de Percy. 20 September. https://soundcloud.com/madepercy/6-on-bipartisanship-reform-fall-guys-asian-century-and-infrastructure-with-michelle-grattan

DuBrin, Andrew J., and Carol Dalglish. (2003). Leadership: an Australasian focus. Milton, QLD: Wiley.

Fiedler, Fred E. (1967). A theory of leadership effectiveness. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Genieys, William (2020). Fact check US: is Obamacare ‘dysfunctional and too expensive’, as Trump claims? The Conversation, 30 October. https://theconversation.com/fact-check-us-is-obamacare-dysfunctional-and-too-expensive-as-trump-claims-149083

Harrington, Clodagh, and Alex Waddan (2020). How much of Barack Obama’s legacy has Donald Trump rolled back? The Conversation, 21 October. https://theconversation.com/how-much-of-barack-obamas-legacy-has-donald-trump-rolled-back-145663

Hawke, R.J. (1987). https://electionspeeches.moadoph.gov.au/speeches/1987-bob-hawke

Hawkins, Kirk (2003). Populism in Venezuela: the rise of Chavismo. Third World Quarterly 24(6): 1137–1160. https://doi.org/10.1080/01436590310001630107

Herodotus (2003 [430 BCE). The histories. London: Penguin.

Hersey, Paul, and Ken H. Blanchard. (1969). Life cycle theory of leadership. Training & Development Journal 23(5): 26–34.

Hofstede, Geert (2011). Dimensionalizing cultures: the Hofstede model in context. Online Readings in Psychology and Culture 2(1). https://doi.org/10.9707/2307-0919.1014

Johnson, Carol, and Blair Williams (2020). Gender and political leadership in a time of COVID. Politics & Gender 16(4): 943–950. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1743923X2000029X

Kamarck, Elaine (2018). The fragile legacy of Barack Obama. Brookings Institution. https://www.brookings.edu/blog/fixgov/2018/04/06/the-fragile-legacy-of-barack-obama/

Keneally, Kristina (2021). Stop right-wing evil feeding online. The Australian, 18 March. https://www.theaustralian.com.au/commentary/stop-rightwing-evil-feeding-online/news-story/8d1dab5715e8a8cf2aa7212126c886cc

King, Albert S. (1990). Evolution of leadership theory. Vikalpa 15(2): 43–56. https://doi.org/10.1177/0256090919900205

King, Gary, Robert O. Keohane and Sydney Verba (1994). Designing social inquiry: scientific inference in qualitative research. Princeton University Press. https://doi.org/10.1515/9781400821211

Lloyd, Graham (2020). Jacinda Ardern: show pony or stayer? The Australian, 27 February. https://www.theaustralian.com.au/inquirer/jacinda-ardern-show-pony-or-stayer/news-story/50062ae173b94270d3445cdaab2ce253

McClure, Tess (2021). Jacinda Ardern suggests opposition leader Judith Collins is a ‘Karen’. The Guardian, 1 July. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2021/jul/01/new-zealand-jacinda-ardern-opposition-judith-collins-leader-karen

McKay, Jessica M. (2020). Opinion: Those calling Jacinda Ardern a ‘show pony’ should trot on, 1 NEWS political editor says. 1 News, 2 March. https://www.tvnz.co.nz/one-news/new-zealand/opinion-those-calling-jacinda-ardern-show-pony-should-trot-1-news-political-editor-says

Morrison, Scott (2019). In our interest. 2019 Lowy Lecture, 3 October, Sydney.

Novak, Lauren (2012). ‘Why I had to knife Kevin Rudd’ – Gillard confirms leadership spill. PerthNow, 24 February. https://www.perthnow.com.au/news/why-i-had-to-knife-kevin-rudd—gillard-confirms-leadership-spill-ng-93230fa9b69966eff0a9ab02fcff6e3b

Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) (2013). Globalisation. OECD Publishing. https://stats.oecd.org/glossary/detail.asp?ID=1121

Pigliucci, Massimo (2017). When I help you, I also help myself: on being a cosmopolitan. Aeon. https://aeon.co/ideas/when-i-help-you-i-also-help-myself-on-being-a-cosmopolitan

Plato (2003 [380 BCE]). The republic. London: Penguin.

Quigg, Lemuel E. (1887). The court of public opinion. North American Review 144(367): 625–630.

Safi, Michael (2015). How giving Prince Philip a knighthood left Australia’s PM fighting for survival. The Guardian, 3 February. https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2015/feb/03/how-giving-prince-philip-a-knighthood-left-australias-pm-fighting-for-survival

Saltman, Richard B., and Odile Ferroussier-Davis (2000). The concept of stewardship in health policy. Bulletin of the World Health Organization 78(6): 732–739.

Santow, Simon (2010). Labor’s shadow men stuck knife into Rudd. ABC News, 24 June. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2010-06-24/labors-shadow-men-stuck-knife-into-rudd/880078

SBS News (2021). Xi Jinping hails China’s ‘irreversible’ rise during Communist Party birthday speech. SBS News, 2 July. https://www.sbs.com.au/news/xi-jinping-hails-china-s-irreversible-rise-during-communist-party-birthday-speech

Shergold, Peter, and Andrew Podger (2021). Neoliberalism? That’s not how practitioners view public sector reform. In A. Podger, M. d. Percy and S. Vincent, eds. Politics, policy and public administration in theory and practice: essays in honour of Professor John Wanna (pp. 335–377). Australia and New Zealand School of Government and ANU Press. https://doi.org/10.22459/PPPATP.2021.14

Silva, Kristian (2019). Former PM Julia Gillard says misogyny speech overshadowed other achievements. ABC News, 16 September. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2019-09-16/julia-gillard-says-misogyny-speech-overshadowed-achievements/11515636

Simon, Herbert A. (1997 [1947]). Administrative behavior. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Talbot, Jonathan (2021). US global rule is coming to an end, says Russian leader. Sky News, 2 July. https://www.skynews.com.au/australia-news/defence-and-foreign-affairs/us-global-rule-is-coming-to-an-end-says-russian-leader/news-story/a8987b0ef15bddf2d34c5289abe3de2a

Thucydides (1972 [411 BCE]). History of the Peloponnesian War. London: Penguin.

Tulich, Tamara, Ben Reilly and Sarah Murray (2020). The National Cabinet: presidentialised politics, power-sharing and a deficit in transparency. AUSPUBLAW, 23 October. https://auspublaw.org/2020/10/the-national-cabinet-presidentialised-politics-power-sharing-and-a-deficit-in-transparency

van Beurden, Pieter, and Tobias Gössling (2008). The worth of values: a literature review on the relation between corporate social and financial performance. Journal of Business Ethics 82(2):407–424. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-008-9894-x

Von Clausewitz, Carl (1982 [1832]). On war. London: Penguin.

Von Drehle, David (2016). Honor and effort: what President Obama achieved in eight years. Time, 22 December. https://time.com/4616866/barack-obama-administration-look-back-history-achievements/

Zelizer, Julian E., ed. (2018). The presidency of Barack Obama: a first historical assessment. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. https://doi.org/10.23943/9781400889556

Zinn, Christopher (2019). Bob Hawke obituary. The Guardian, 16 May. https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2019/may/16/bob-hawke-obituary

About the authors

Dr Michael de Percy FCILT is senior lecturer in political science at the Canberra School of Politics, Economics, and Society, University of Canberra. He holds a PhD in political science from the Australian National University, a Bachelor of Philosophy (Honours) from the University of Canberra, and a Bachelor of Arts from Deakin University. He is a graduate of the Royal Military College, Duntroon, where he received the Royal Australian Artillery prize. He is a Fellow of the Chartered Institute of Logistics and Transport, and he is an editor of the Journal of Telecommunications and the Digital Economy.

Dr Stewart Jackson is a former youth worker, public servant, political operative, and now senior lecturer in politics at the University of Sydney. His PhD examined the internal organisation of Australian Greens, stemming from a 30-year engagement with green politics as a researcher, campaigner, and organiser. His broad interests cover the breadth of Green politics in Australia and the Asia Pacific, with a special interest in party development. He has written previously on campaigning, leadership and social movement activism.

- Michael de Percy and Stewart Jackson (2024). Political leadership. In Nicholas Barry, Alan Fenna, Zareh Ghazarian, Yvonne Haigh and Diana Perche, eds. Australian politics and policy: 2024. Sydney: Sydney University Press. DOI: 10.30722/sup.9781743329542. ↵

- Davis 2011. ↵

- Bonaparte 2010 [1916], 7. ↵

- Plato 2003 [380 BCE]. ↵

- See Thucydides 1972 [411 BCE]. ↵

- Clawson 2012, 11–23. ↵

- Herodotus 2003 [430 BCE]. ↵

- van Beurden and Gössling 2008. ↵

- King 1990. ↵

- Clawson 2012, 11–23. ↵

- Burns 2012 [1978], 1. ↵

- Blake, Mouton and Bidwell 1962. ↵

- Zinn 2019. ↵

- Safi 2015. ↵

- Hersey and Blanchard 1969. ↵

- Fiedler 1967. ↵

- DuBrin and Dalglish 2003, 8–9. ↵

- See Simon 1997 [1947]. ↵

- Tulich, Reilly and Murray 2020. ↵

- See DuBrin and Dalglish 2003, 6–9. ↵

- See Hofstede 2011. ↵

- Burns 2012 [1978]. ↵

- Boese, Edgell, Hellmeier, Maerz and Lindberg 2021. ↵

- Burns 2012 [1978], 258. ↵

- Burns 2012 [1978], 308–9. ↵

- Von Drehle 2016. ↵

- Kamarck 2018. ↵

- Genieys 2020. ↵

- Zelizer 2018. ↵

- Harrington and Waddan 2020. ↵

- Holden 2013. ↵

- See Pascoe 2017 on the complexities of the current GST arrangements resulting from the original political agreements. ↵

- Davis 2011. ↵

- Novak 2012; Santow 2010. ↵

- Davis 2011, 1. ↵

- McKay 2020. ↵

- McClure 2021. ↵

- Silva 2019. ↵

- De Percy 2017. ↵

- Treasury 2021. ↵

- Johnson and Williams 2020, 944–45. ↵

- Johnson and Williams 2020, 944–45. ↵

- Keneally 2021. ↵

- Lloyd 2020. ↵

- Burns 2012 [1978], 404. ↵

- Hawke 1987. ↵

- Burns 2012 [1978], 2. ↵

- Shergold and Podger 2021. ↵

- OECD 2013. ↵

- Morrison 2019. ↵

- SBS News 2021. ↵

- Talbot 2021. ↵

- Hawkins 2003, 1138. ↵

- Quigg 1887. ↵

- Burns 2012 [1978], 1. ↵

- Treasury 2021. ↵

- The authors wish to thank Emeritus Professor John Wanna for allowing parts of a jointly authored (with Michael de Percy) work in progress on stewardship to be adapted for parts of this section. ↵

- Saltman and Ferroussier-David 2000, 732. ↵