31 Making public policy

John R. Butcher and Trish Mercer

Key terms/names

Australian policy cycle, evidence-based policy, implementation failure, policy analysis, policy design, policy evaluation, policy implementation, policy making, policy process, policy theory, policy value chain

It is commonly believed that Australians are uninterested in politics.[1] Whatever the truth of this proposition, voters are generally interested in government policies that they believe will affect them, although the manner in which policy is made remains opaque for many.

We argue that public indifference to how policy is made is problematic. Policy making affects the life of every person residing in Australia; it shapes the social, economic and physical environments in which we act out our lives. The policy process itself can also have repercussions for society and communities, particularly when community opinion about policy options is divided. An example is the emotionally charged public debate leading to the passage of legislation allowing for marriage equality in Australia.[2]

Policy making is, in part, an exercise in rational problem solving. It is also an intensely political process and requires the judicious consideration and balancing of complex issues, including public opinion, competing interests, social relations and the distribution of power within a society. A recent example is the South Australian Murray–Darling Basin Royal Commission, which found that policy governing the management of water resources was largely driven by political considerations, ‘not science’.[3]

For the most part, policies begin as statements of values and intent. Policies often have an ideological foundation, and are frequently portrayed as occupying part of a spectrum ranging from left to right. For example, governments or parties of the right or centre-right might be characterised as favouring market forces over government intervention, individual rights over collective rights and unilateralism over multilateralism. Governments of the left are typically portrayed as favouring government intervention in social and economic affairs, emphasising collective rights and preferring multilateral approaches to problem solving.

Such characterisations are, of course, simplistic. Governments of the right sometimes resort to intrusive uses of state power despite the value placed on individual sovereignty, and governments of the left sometimes resort to market mechanisms to address distributional inefficiencies.

This chapter aims to help students to understand:

- what policy is

- how policy happens

- the principal theoretical constructions of the policy process

- key approaches to understanding the policy process

- the contestable nature of public policy

- the importance of evidence-based policy

- the craft of policy making

- the importance of policy analysis and policy instruments

- the task of policy implementation

- the implications of policy failure.

What is ‘policy’?

This chapter is primarily concerned with formal expressions of government – or public – policy:

- as a set of values and convictions

- as operational rules designed to comply with legal requirements

- as embodied in law in the form of primary legislation or regulation.

In each case, the formal expression of policy gives form and consequence to policy intent.

Almost every aspect of our lives is affected by policy; policy affects our birth, the manner in which we are raised and educated, our access to health care, the quality of our physical environment, how we conduct ourselves, whom we might marry, our access to employment, our rights at work, our access to housing, how we raise our children and even the quality of our deaths and what we are able to pass on to the generations succeeding us.

In broad terms, policy can be said to represent preferred responses to problems. For any given problem there might be a number of available responses. For example, the statement ‘anyone who attempts to travel illegally by boat to Australia will be turned back to their country of departure’ is a declaration of policy. It sets out a preferred response under defined circumstances. To the extent that such a statement sets out a preferred response, it also precludes other potential responses.

Policy provides a framework for what can and ought to occur in prescribed situations. However, policy is also malleable and is subject to interpretation and adjustment as circumstances change. Changing expectations, attitudes, beliefs, values and behaviours often lead, eventually, to changes in government policy. Laws allowing same-sex marriage, assisted dying or the recreational use of cannabis represent policy responses to cultural changes. Similarly, technological change and environmental changes – think of digital technology, automation or climate change – have fuelled a demand for adaptive policy responses (as well as entrenching resistance to change in some sections of the polity). Likewise, changes in the economy and in our systems for production have driven adaptive changes in policies pertaining to industry, consumer law, employment, education and finance (among others).

How does policy happen?

Public policy can be a messy business. The 19th-century American poet, John Godfrey Saxe, is reported to have written ‘Laws, like sausages, cease to inspire respect in proportion as we know how they are made’.[4]

Public policy is an expression of political intent and a framework for action. Political parties or groupings, in and out of government, will have a set of policies – a policy platform – covering a broad and diverse range of matters. Ideally, policy platforms are internally consistent and represent a coherent narrative for governance. This is not always the case, and the highly contested nature of public policy sometimes means that governing parties bring contradictory positions to the business of government.

For a problem to be considered deserving of a policy response – having what the influential political scientist John Kingdon[5] refers to as ‘policy salience’ – there first needs to be:

- broad agreement that a problem exists

- a broadly shared understanding about the nature of the problem

- a broad acceptance of available solutions.

Moreover, propositions about the existence and nature of problems, not to mention the nature of possible solutions, need to be tested in a variety of forums: for example, within the broader community and the electorate; within communities of interest, including geographical regions, industry sectors and civil society; within professional ‘epistemic’ communities of subject area specialists; and within political parties themselves.

The existence and importance of ‘problems’ is often highly contested, both in the community at large and within political parties. Even where there is broad agreement about problems, ‘solutions’ are often controversial. There are many reasons why it is difficult to reach a majority view about the nature of policy problems and preferred solutions. Different actors and stakeholders bring different things to the table and their perspectives are shaped by their lived experience, education, qualifications, attachment to particular interests, attachment to community, ideology, religious beliefs and personal convictions.

Policy makers also need to be attuned to perceptions of ‘winners and losers’. In other words, who benefits from the policy and who perceives themselves to be adversely affected by the policy? They also need to be aware of the potential for ‘interests’ (e.g. civil society organisations, industry groupings, communities) to mobilise for or against policy proposals. Taking all of these factors into account, it is easy to see why it can be so difficult to reach agreement about problems and solutions.

Theoretical perspectives

In his book Analyzing public policy, Peter John[6] outlines the principal approaches for understanding the policy-making process:

- Institutional approaches, which take the view that that political organisations – such as parliaments, legal systems and bureaucracies – shape public decisions and policy outcomes.[7]

- Groups and network approaches, which claim that associations and informal relationships, both within and outside political institutions, shape decisions and outcomes. These approaches not only consider the effects on policy of unique relationships between groups and entities, they also embrace the idea that networks of relationships affect policy outputs and outcomes.[8]

- Exogenous approaches, which assert that factors external to the political system determine the decisions of public actors and affect policy outputs and outcomes.[9]

- Rational actor approaches, which claim that the preferences and bargaining of actors explain decisions and outcomes. This approach is often called ‘rational choice’.[10]

- Ideas-based approaches, which hinge on a view that ideas about solutions to policy problems have a life of their own, and that ideas circulate and gain influence independently in the policy process.[11]

Theoretical perspectives such as these are useful in helping us to understand the policy-making process as a social, cultural, historical and political phenomenon. Each allows us to consider some facet of policy making and to understand the nature of the environment in which policy occurs.

While each of these approaches serves a particular intellectual purpose and reflects particular ‘truths’ about how policy comes to be, none tells the whole story. Nor are they necessarily mutually exclusive (e.g. many institutional accounts also rely heavily on rational actor thinking).

The reality is that making public policy is a complex social behaviour and any given policy exhibits the influences of multiple institutions, groups and networks, exogenous factors, preferences and ideas generated within epistemic communities.

A marketplace of ideas

Public policy might best be described as a marketplace of ideas and prescriptions for the broad and diverse array of matters that need to be actively governed in order for human society to function. It involves making difficult choices and negotiating multiple trade-offs between competing options. Moreover, this is a highly contestable marketplace, especially in liberal democratic societies like Australia’s.

Policy practitioners need to be mindful of the ideological leanings and philosophical underpinnings of governing parties. It is also important for them to understand the policy leanings of non-governing opposition and minor parties in order to anticipate possible resistance to policy proposals and advise government about policy compromises that might be broadly acceptable to legislatures.

Although Australia’s polity is often portrayed as a ‘two-party system’, our parliaments are generally made up of representatives from multiple parties as well as independents who have no formal party affiliation. And although electoral contests in all Australian jurisdictions usually involve competition between two major parties – in most cases, the Australian Labor Party and the Liberal Party of Australia (an exception being Queensland, where the Liberal and National parties merged in 2008) – Australian parliaments are usually dominated by three, and sometimes four, established political parties.

Even non-governing parties and members of parliament – including minor parties, ‘micro parties’ and independents – can exert influence on policy, especially when governments do not enjoy a numerical majority in both the upper and lower parliamentary chambers (the exceptions being Queensland, the Australian Capital Territory and the Northern Territory, which are ‘unicameral’, meaning they have only one legislative chamber).

A strong indication of the policy predispositions of Australia’s major political parties can be found in their platform statements:

- Australian Labor Party: ‘Labor members continue to work towards a goal of better services, greater opportunity and a fair go for all Australians.’

- Liberal Party of Australia: ‘In short, we simply believe in individual freedom and free enterprise.’

- The National Party: ‘The Nationals are dedicated to delivering future security, opportunity and prosperity for all regional Australians.’

- The Australian Greens: ‘Peace and Non Violence, Grassroots Democracy, Social and Economic Justice, Ecological Sustainability.’

- Pauline Hanson’s One Nation: ‘To bring about the necessary changes for fair and equal treatment of all Australians within a system of government recognising, and acting upon, a need for Australia to truly be one nation.’

It must be admitted that when in power governments do not always adhere faithfully to the ideological positions they espoused when in opposition. Governments are usually obliged to take a pragmatic view and work within constraints imposed by the political, social and economic environment in which they are situated.

A contest of interests

Public policy is also the concern of particular interests in society, and it can be said that some policy settings can become captive to particular interests.

Policy is often vigorously contested within political parties, a prime example being the internal debate within the federal Liberal Party around the question of climate change and strategies to reduce carbon emissions; within the federal Labor Party one finds sometimes rancorous debate about the treatment of asylum seekers.

Policy proposals from government might also be challenged by a variety of interests, including industry sectors (e.g. the Minerals Council of Australia), professional groupings (e.g. the Australian Medical Association), trade unions (e.g. the Construction, Forestry, Maritime, Mining and Energy Union or CFMEU), civil society organisations (e.g. the Australian Council of Social Service) or consumer lobbies (e.g. CHOICE). These interests represent stakeholders that stand to be affected in some way by government policy. In general, policy makers seek to consult with affected interest groups (usually through their representative organisations) in the formulation and implementation of policy. Politically powerful interests can wield significant – and sometimes disproportionate – influence. Australian examples include the first Rudd Labor government’s attempt to introduce a Minerals Resource Rent Tax and the Gillard Labor government’s national gambling reforms – these measures were staunchly resisted by industry interests and subsequently wound back.

An evidentiary basis?

In an ideal world, policy responses would have some kind of evidential basis. This might mean a combination of empirical research, statistical analysis, comparative policy studies, public consultation, evaluation studies or other forms of evidence that can be made available for independent scrutiny.[12] However, ours is not an ideal world, and the evidence base for many public policy choices is often selective, sometimes even to the point where decision makers find themselves accused of ‘policy-based evidence making’ – a pejorative converse of the term evidence-based policy making.

‘Policy-based evidence making’ means working backwards from a predefined policy position with the aim of finding evidence that supports decisions that have already been made.[13] It is possible that the growing trend of governments engaging private consultancy firms to produce commissioned research as an input into policy development has contributed to the perception that evidence is often crafted to fit policy preferences.[14] It is also not unknown for special interests or lobby groups to produce commissioned research (of varying quality) in support of their advocacy for policy change.

Policy making is subject to bounded rationality – meaning that the decisions of policy makers are constrained by a variety of factors, such as the tractability of the problem at hand, the availability of information and the time frame within which decisions must be made. There will be times when the ‘evidence’ either fails to support, or directly contradicts, the preferred policy positions of governments, and it is not unknown for contradictory evidence to be suppressed in order to ‘protect’ policy settings that are based more in ideology or moral conviction than in any objective appraisal of the circumstances.

Finally, if evidence is to have an impact on policy governance and management, systems that are capable of incorporating new information into decision making are required. This is a perennial problem for public sector organisations, which often fail to use evaluative data generated in the course of delivering public policy to make adjustments to policy settings and/or to the service delivery architecture.[15]

Practical policy formulation

It is government’s role to set policy objectives, and it is the duty of the public service to advise government about the technical, political and economic feasibility of those policy objectives, including any risks that might arise in their implementation. Having ‘advised’ government, the public service is obliged to give effect to government policy by developing an implementation strategy (in consultation with the government), including formulating a budget, identifying relevant internal and external capability and undertaking appropriate consultations with affected stakeholders.

It is also the responsibility of the public service to manage any risks arising in the implementation and operational phases. Policy implementation can be subject to a wide variety of constraints, such as short time frames, availability of resources, technical practicability, a lack of appropriate legal authority (an example being the Gillard government’s ‘Malaysia solution’, which aimed to develop a regional strategy to redirect boat arrivals in Australia), inability to pass enabling legislation in parliaments (an example is the Turnbull Liberal–National Coalition government’s withdrawal of proposed corporate tax cuts legislation in 2018) and community/ stakeholder resistance. The public service often bears the brunt of any fallout associated with ineffectual or misguided policy formulations (such as the Rudd government’s GROCERYchoice and FuelWatch initiatives).

In Australia, public servants typically acquire their policy skills ‘on the job’ in the form of ‘craft knowledge’.[16] Indeed, it is unusual for Australian public servants – unlike their North American counterparts – to enter the public service with formal training in public administration, public policy or political science. Although increasing numbers of public servants now undertake postgraduate qualifications in disciplines related to public policy, there remains a degree of scepticism among public servants about the relevance of academic learning to the ‘craft’ of public policy making.[17]

Policy practitioners who seek to learn about the policy process will discover an extensive theoretical literature, aimed primarily at academics, that is not easily translatable to the real world situations confronting them.[18] This literature is also characterised by vigorous – and often acrimonious – debate about the limitations of certain models.

Until the late 1950s, policy making was predominantly portrayed as a process of rational analysis culminating in a value-maximising decision. However, American political scientist Charles Lindblom (1917–2018) regarded the rational policy process as an unattainable ideal and proposed an alternative model, incrementalism, which focused less on abstract policy ideals and placed greater emphasis on solving concrete problems.[19] Often described as ‘muddling through’, incrementalism describes an iterative process of building on past policies and reaching broadly agreed positions among diverse stakeholders.[20] Incrementalism offers a plausible account of the policy-making process. In particular, Lindblom’s emphasis on ‘trial and error’ would resonate with many contemporary public servants.[21]

The ‘Australian policy cycle’

Originally developed 20 years ago specifically for an Australian practitioner audience, the ‘Australian policy cycle’ is an enduring – if somewhat idealistic – model of the policy development process. The model is a signature feature of The Australian policy handbook, first published in 1998. Published in its 6th edition in 2018 and billed as a ‘practical guide to the policy making process’, the handbook has been described as a ‘popular “go to” policy survival manual for public servants’.[22]

Whereas theoretical models of the policy process seek explanations through investigations of institutional, political, organisational and cultural factors that shape the policy environment, the ‘Australian policy cycle’ is more of a ‘how to’ guide and presents policy making as a sequence of practical actions. It is intended as ‘a pragmatic guide for the bewildered’; the handbook’s authors assert that ‘good policy should include the basic elements of the cycle’.[23] The strength of the model is its practical approach, which captures the entirety of policy development and implementation, although it does not supply causal explanations of policy.

A policy cycle approach can help public servants develop a policy and guide it through the institutions of government. The policy cycle starts with a problem, seeks evidence, tests proposals and puts recommendations before Cabinet. Its outcomes are subject to evaluation and the cycle begins again. The policy cycle offers a modest and flexible framework for policy makers.[24]

The policy cycle model has been criticised for suggesting a far more linear and logical progression of activities than would ever be observed in practice.[25] Critics also point out that the model does not accurately capture the lived experience of policy professionals.[26] The Australian policy handbook’s authors, Althaus, Bridgman and Davis, have engaged openly with such critics and have responded to their criticisms in the following terms: ‘The policy cycle does not assert that policy making is rational, occurs outside politics, or proceeds as a logical sequence rather than as a contest of ideas and interests’.[27]

In simple terms, the policy cycle entails eight logically sequenced steps:

- identify issues

- analyse policy options

- select policy instruments

- consult affected parties

- co-ordinate with stakeholders

- decide preferred strategy

- implement policy

- evaluate success/failure.

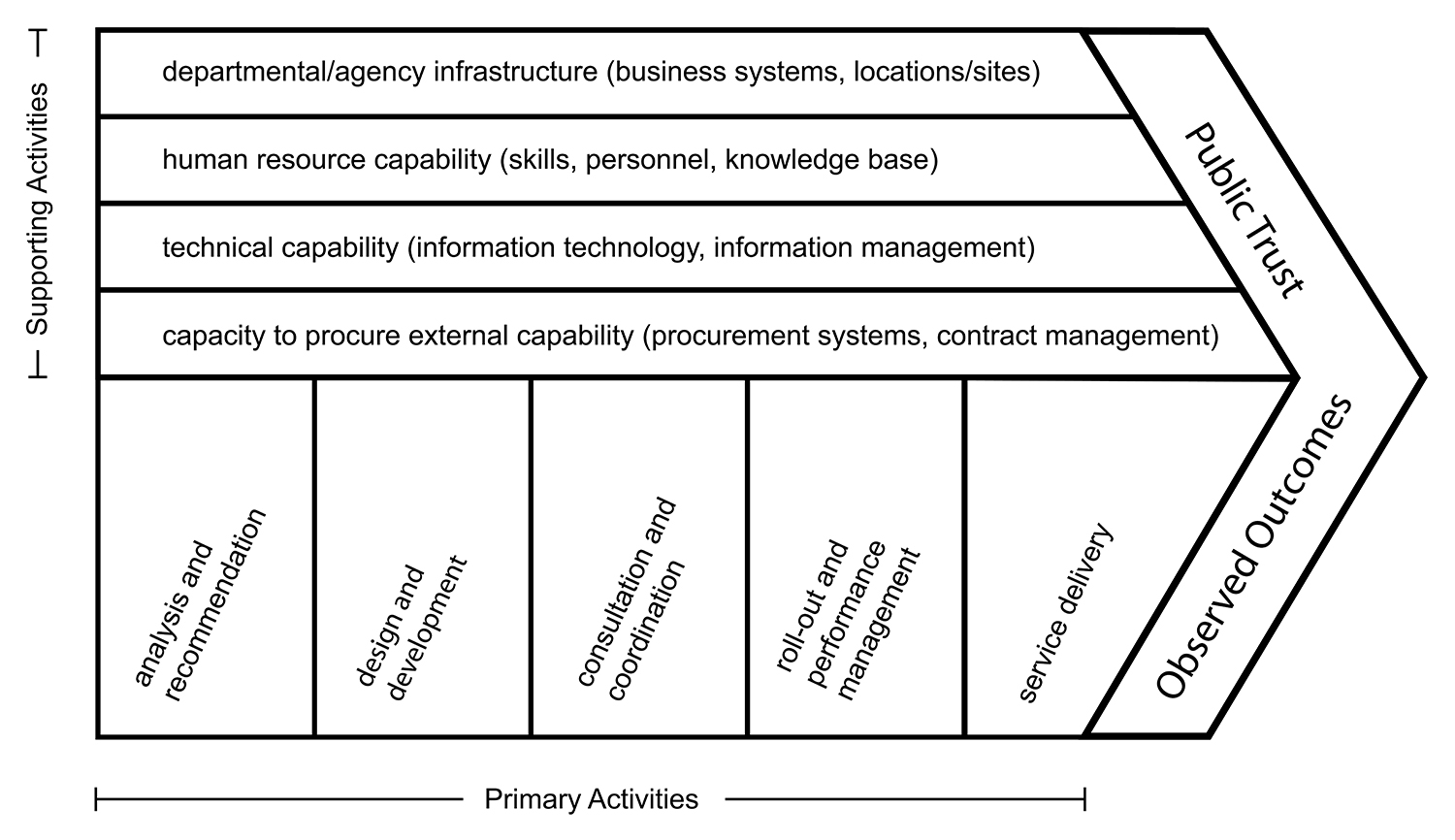

Notably, the policy cycle offers little guidance to the aspiring policy practitioner about the technical feasibility and integrity of the policy development and implementation phases. In this regard, we might wish to consider the ‘policy value chain’ (presented in Figure 1).

Based upon a concept developed by Michael Porter,[28] value chain analysis takes account of the primary activities that need to be undertaken to produce value for customers, and the supporting activities and systems necessary for primary activities to occur. Porter’s model was developed to guide the commercial decision making of enterprises; however, it can be recast as a policy value chain that can be used to help policy practitioners understand the activities that need to be undertaken sequentially to shepherd a policy from conception through to implementation, as well as the organisational capabilities or functions required to support those activities. In the policy value chain, primary activities are analogous to the steps set out in the ‘Australian policy cycle’. Supporting activities encompass the following essential organisational and management capabilities and assets:

- organisational infrastructure (including research capability and knowledge management systems)

- human resources (capacity to assign people with relevant knowledge and skills to a task and support them in that task)

- technical capability (including information technology, communications and business platforms)

- capacity to procure external capability (including the ability to recruit people with relevant skills or to engage consultants with relevant expertise).

Where Porter’s original model posits margins (profit) as the primary value produced by the deployment of capability to support the creation of value, in the policy value chain we might substitute outcomes and public (or stakeholder) trust as the primary value created by public policy. The public value of policy is sometimes overlooked by policy theorists – who focus instead on the character of political or power relations culminating in a particular policy – and by those analysts who look only at the ‘craft’ aspects of the policy process, while being agnostic about the impact of policy on the public good. Our adaptation of Porter’s value chain model expressly invites the policy maker to keep public value creation ‘front of mind’.

Cross-portfolio policy co-ordination

Policy generated in one ministry or portfolio can have impacts on policy in other ministries, portfolios and agencies. Similarly, policies originating in one jurisdiction can have consequential implications for intergovernmental relations, including between national (federal) and subnational (state, territory and local) governments (one example being the impact of changes in revenue or spending decisions by the Commonwealth government upon state/territory governments) and between nations in respect of multilateral or bilateral agreements (examples being trade agreements or United Nations conventions).

In Australia, central agencies of government – Departments of Prime Minister and Cabinet or Premier and Cabinet/Chief Minister – perform an essential policy co-ordination role. It falls to these agencies to review policy and budget proposals emanating from ministers and their departments and to seek comment from other ministries and agencies in order to identify any unintended consequences that might arise. Once comments have been compiled from affected agencies – including other central agencies, such as Departments of Treasury and Finance as well as agencies responsible for government revenue – a briefing, together with recommendations, will be prepared for the consideration of Cabinet. Vetting of this nature often requires specialist knowledge of particular policy domains and of the statutory basis for government programs and services. It also depends less on political theory and more on an appreciation of the practical and pragmatic dimensions of public policy.

Policy analysis

The aphorism ‘the best is the enemy of the good’, commonly attributed to the French Enlightenment writer and philosopher Voltaire (1694–1778), neatly encapsulates a key challenge of public policy. At some level, all policy decisions represent compromises between different interests and involve considerations about political acceptability as well as economic and technical feasibility. To quote the 19th-century German statesman Otto von Bismarck, ‘politics is the art of the possible’ – likewise, policy is the art of the achievable.

Policy analysis is an important part of the ‘craft’ of policy making. The task of the analyst is to understand the implications of policy decisions in terms of their impact on the policy problems being addressed; any unintended consequences for government or the community; and their legal, economic and technical soundness. Policy analysis is essential for the provision of policy assurance and enables the analyst to provide answers to the following key questions:

- Is the policy well targeted?

- Is the policy delivery architecture well designed?

- How will performance be measured?

- How will we know if the policy is working?

- If the policy is not working, what corrective action is available?

In order to make reliable pragmatic judgements about such matters, it is important for the analyst to give close consideration to a wide range of factors. The kinds of questions the astute policy analyst might ask include:

- Is the policy framed within a particular political or philosophical perspective, and is it consistent with the values and policy platform of the governing party or parties?

- Is the policy genuinely directed towards solving a problem in public policy, or does it primarily seek to solve a ‘political’ problem by creating the impression of action while having little tangible effect?

- Have similar policies been pursued in other jurisdictions and to what effect? How might past experience inform policy implementation?

- What are the competing options to achieve the policy aims, and how do they compare? Does the policy require enabling legislation? What policy instruments or tools are available to give effect to the policy? What are the expected/hoped for impacts of the policy, and how might these be reliably measured and reported?

- Which groups or communities of interest – including classes of workers, trade unions, professional associations, advocacy organisations, industry groupings, communities and/or geographical regions and expected beneficiaries – stand to be affected by the policy and in what manner,?

- Does the infrastructure exist to give effect to the policy? Is there a functioning market framework within which the policy might be delivered? What skills base is necessary to deliver the policy? Is an appropriately skilled workforce available? What capacity exists within the public and non-state sectors to give effect to the policy?

- What will policy implementation cost? Is it affordable? Will delivery be selectively targeted, means-tested or otherwise ‘rationed’? Is it possible to offset expenditure through some form of cost recovery, such as user fees? What are the principal cost drivers in the policy space?

- How will the policy be delivered and governed? What systems or frameworks need to be established to provide assurance to government that policy implementation and delivery will occur within prescribed timeframes and budgets? What systems or frameworks are available to ensure that the policy is performing in the expected manner?

- Has provision been made for periodic evaluations of the effectiveness of the policy and/or the operational arrangements established to give effect to the policy, and is there a capacity to make necessary adjustments to the policy and/or management structures should evaluation findings so indicate?

Policy instruments

Policy instruments enable the application of policy decisions in practice and can be grouped into the following major categories:

- money (spending and taxing powers)

- law (including regulation)

- government action (e.g. delivering services)

- advocacy (e.g. educating, persuading)

- networking (e.g. cultivating and using relationships to influence behaviour)

- narratives (e.g. using storytelling and communication – including public advertising)

- behavioural economics (e.g. using economic incentives to induce behaviour change, or ‘nudging’ as it has come to be known).[29]

It should be noted that in the real world these categories often overlap and a mix of instruments is generally required. For instance, governments might elect to use a form of direct service delivery (government action) to achieve policy aims; the delivery of services requires statutory authority (law), is funded by government appropriations (money) and employs ‘nudge’ strategies (behavioural economics), advertising (narratives) and public education (advocacy) to achieve the government’s policy aims.

Government policies aimed at reducing the harms from the use of tobacco products provide a good example; they employ all of the instruments named above:

- Money: the collection of excise tax on cigarette sales to provide a source of funds for medical research and for non-government organisations involved in anti-smoking programs.

- Legislation/regulation: setting age restrictions on the purchase of tobacco products, banning smoking in public places and restricting the sale, advertising, distribution and packaging of tobacco products.

- Government action: funding the delivery of preventative health services aimed at assisting smokers to quit.

- Advocacy: there have been multiple education campaigns on the health risks associated with tobacco and how to quit.

- Networking: successive governments have entered into partnerships with representative bodies, such as the Australian Medical Association, and non-government organisations advocating smoking reduction.

- Narratives: anti-smoking campaigns utilising various media and featuring testimonials by former smokers and/or portraying the health and other impacts of smoking on real people.

- Behavioural economics: levying excise taxes to increase the purchase price of tobacco products and/or offering financial incentives to quit smoking.

It is worth noting that the choice of policy instrument is all too often a function of familiarity, as opposed to optimal fitness for purpose (in other words, policy makers stick to what they know). Other factors influencing the choice of instruments include:

- the characteristics of the policy area in question (e.g. some policy areas might have a long history of recourse to particular models of implementation, and this predisposes policy actors in those areas to prefer those models)

- available resources (e.g. some policy instruments might entail significantly higher establishment and running costs than others, or they might require skills or technologies that are in short supply, leading to the selection of less optimal but more feasible options)

- ease of administration and/or administrative traditions (e.g. some policy instruments might be inherently easier to administer, while others entail greater complexity and risk; in some policy domains particular traditions – say, centralised, hierarchical management frameworks, as opposed to decentralised, distributed frameworks – might predominate, predisposing practitioners towards the selection of instruments that ‘fit’ with the existing administrative culture)

- the political dimension (e.g. recourse to particular policy instruments might be precluded because they are not considered to be acceptable to the community and/or they might be unacceptable to governments on ideological grounds).[30]

Policy implementation

The true test of any policy lies in its implementation. The Australian Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet sets out a structured approach to thinking about how a policy or program will be delivered, framed around seven principles drawn from lessons learnt by frontline staff involved in implementation and delivery:

- planning

- governance

- engaging stakeholders

- risks

- monitoring, review and evaluation

- resource management

- management strategy.

Implementation gives practical effect to policy. It is a complex process requiring application of a range of technical and management skills. Many seemingly ‘good’ policies fail in their implementation, resulting in a failure to achieve expected outcomes or in unintended ‘perverse’ outcomes.

Implementation failure

Implementation failure can occur anywhere along the policy value chain and can be caused by any combination of:

- inadequate research, design and planning

- poor co-ordination and inadequate consultation with stakeholders

- insufficient resourcing and capacity constraints

- legislative and regulatory gaps

- proceeding too quickly and/or failure to ‘pilot’

- failure to anticipate and/or effectively manage risks

- ineffective governance and/or administrative architecture

- multiple and/or incompatible policy goals.

Implementation failure entails significant costs in terms of finite resources (such as money, labour and time), reputation and trust. These include a failure to realise intended policy aims; loss of public confidence; costs of restoration, rectification or redress; costs arising from bringing failed programs to a premature end; lost opportunities (opportunity costs); and, for governments, loss of political capital (with potential electoral consequences). It is important to recall that policy making is, and remains, inherently ‘political’ and that ‘policy success’ will always be a contested assessment. Indeed, it might be said that ‘failure’ has been ‘weaponised’ in Australia’s contemporary political culture.

Conclusions

In this chapter we have attempted to introduce readers to a spectrum of ideas about the nature, formulation and ‘craft’ of policy making. In so doing, we have tried to:

- acquaint readers with the major theoretical approaches to understanding the policy process

- equip readers to more effectively understand past and present policy debates

- enable readers to interrogate the processes of policy development, implementation and evaluation.

Policy design and implementation is a complex and imperfect process that is often seen as more of a ‘craft’ than a formal discipline. Policy professionals tend to ‘learn on the job’, and even those who have formal qualifications in public policy or exposure to the academic study of policy often find that the pragmatic reality of policy making aligns poorly with policy theory.

The Australian policy cycle and the policy value chain offer sound practical templates for policy design and evaluation. Unfortunately, as will be attested by many policy professionals working within government, ‘policy craft’ is seldom conducted in full accordance with such orderly, rational models.

In contemporary policy spaces, effective policy craft increasingly comes down to working effectively within networks inside and outside government. Today’s policy professional needs to be acutely aware that governments have many sources of policy advice and that many of these sources have vested interests in particular outcomes. Above all, a capacity for critical reflection and an ability to anticipate the risks and consequences of policy choices provide the foundation of sound policy practice.

It is our hope that the concepts canvassed in this chapter will assist readers to make sense of scholarly and media accounts of policy histories and policy making in different domains and of the changing role, form and modus operandi of the public sector.

References

Adams, David, H.K. Colebatch and Christopher K. Walker (2015). Learning about learning: discovering the work of policy. Australian Journal of Public Administration 74(2): 101–11. DOI: 10.1111/1467-8500.12119

Althaus, Catherine, Peter Bridgman and Glyn Davis (2018). The Australian policy handbook, 6th edn. Crows Nest, NSW: Allen & Unwin.

—— (2015). Learning about learning: discovering the work of policy by Adams, Colebatch, and Walker. Australian Journal of Public Administration 74(2): 112–3. DOI: 10.1111/1467-8500.12145

—— (2007). The Australian policy handbook, 4th edn. Crows Nest, NSW: Allen & Unwin.

Banks, Gary (2018). Whatever happened to ‘evidence-based policy making’? The Mandarin, 30 November. https://bit.ly/48YlBju

Braun, Dietmar, and Andreas Busch (1999). Public policy and political ideas. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar Publishing.

Bridgman, Peter, and Glyn Davis (2003). What use is a policy cycle? Plenty, if the aim is clear. Australian Journal of Public Administration 62(3): 98–102. DOI: 10.1046/j.1467-8500.2003.00342.x

—— (1998). Australian policy handbook. St Leonards, NSW: Allen & Unwin.

Cairney, Paul (2015). How can policy theory have an impact on policy making? The role of theory-led academic–practitioner discussions. Teaching Public Administration 33(1): 22–39. DOI: 10.1177/0144739414532284

Colebatch, H.K. (2006). Beyond the policy cycle: the policy process in Australia. Crows Nest, NSW: Allen & Unwin.

Davies, Huw T.O., and Sandra M. Nutley (2000). What works? Evidence-based policy and practice in public services. Bristol; Chicago: Policy Press.

Dowding, Keith (1995). Model or metaphor? A critical review of the policy network approach. Political Studies 43(1): 136–58. DOI: 10.1111/j.1467-9248.1995.tb01705.x

Gill, Zoe, and H.K. Colebatch (2006). Busy little workers: policy workers’ own accounts. In H.K. Colebatch, ed. Beyond the policy cycle: the policy process in Australia, 240–65. Crows Nest, NSW: Allen & Unwin.

Gould, Stephen Jay, and Niles Eldredge (1977). Punctuated equilibria: the tempo and mode of evolution reconsidered. Paleobiology 3(2): 115–51. DOI: 10.1017/S0094837300005224

Hall, Peter A., and Rosemary C.R. Taylor (1996). Political science and the three new institutionalisms. Political Studies 44(5): 936–57. DOI: 10.1111/j.1467-9248.1996.tb00343.x

Hayes, Michael T. (2002). The limits of policy change: incrementalism, worldview, and the rule of law. Washington DC: Georgetown University Press.

Head, Brian, and Kate Crowley (2015). Policy analysis in Australia, volume 6. Bristol, UK; Chicago: Policy Press.

Hill, Michael (2014). The public policy process, 6th edn. Abingdon, UK: Routledge.

Howlett, Michael (2009). Predictable and unpredictable policy windows: institutional and exogenous correlates of Canadian federal agenda-setting. Canadian Journal of Political Science 31(3): 495–524. DOI: 10.1017/S0008423900009100

Howlett, Michael, and Benjamin Cashore (2009). The dependent variable problem in the study of policy change: understanding policy change as a methodological problem. Journal of Comparative Policy Analysis 11(1): 33–46. DOI: 10.1080/13876980802648144

Howlett, Michael, Allan McConnell and Anthony Perl (2017). Moving policy theory forward: connecting multiple stream and advocacy coalition frameworks to policy cycle models of analysis. Australian Journal of Public Administration 76(1): 65–79. DOI: 10.1111/1467-8500.12191

Howlett, Michael, and Andrea Migone (2013). Policy advice through the market: the role of external consultants in contemporary policy advisory systems. Policy and Society 32(3): 241–54. DOI: 10.1016/j.polsoc.2013.07.005

Howlett, Michael, Ishani Mukherjee and Joop Koppenjan (2017). Policy learning and policy networks in theory and practice: the role of policy brokers in the Indonesian biodiesel policy network. Policy and Society 36(2): 233–50. DOI: 10.1080/14494035.2017.1321230

John, Peter (2012). Analyzing public policy, 2nd edn. Abingdon, UK: Routledge.

—— (2003). Is there life after policy streams, advocacy coalitions, and punctuations: using evolutionary theory to explain policy change? Policy Studies Journal 31(4): 481–98. DOI: 10.1111/1541-0072.00039

Katsonis, Maria (2019). Bridging the research policy gap. The Mandarin, 4 February. https://www.themandarin.com.au/102877-research-policy-gap/

Kingdon, John (1995). Agendas, alternatives, and public policies. New York: Longman.

Lindblom, Charles (2018). The science of ‘muddling through’. In Jay Stein, ed. Classic readings in urban planning, 31–40. New York: Routledge.

Linder, Stephen H., and B. Guy Peters (1990). An institutional approach to the theory of policy-making: the role of guidance mechanisms in policy formulation. Journal of Theoretical Politics 2(1): 59–83. DOI: 10.1177/0951692890002001003

Maddison, Sarah, and Richard Denniss (2013). An introduction to Australian public policy: theory and practice, 2nd edn. Cambridge, UK; Melbourne: Cambridge University Press.

—— (2009). An introduction to Australian public policy: theory and practice, 1st edn. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Marmot, Michael G. (2004). Evidence based policy or policy based evidence? Willingness to take action influences the view of the evidence – look at alcohol. British Medical Journal 328(7445): 906–7. DOI: 10.1136/bmj.328.7445.906

Murray–Darling Basin Royal Commission (2019). Murray–Darling Basin Royal Commission Report. Adelaide: Government of South Australia.

Neilsen, Mary Anne (2012). Same-sex marriage: law and Bills digest. Canberra: Parliament of Australia. https://www.aph.gov.au/About_Parliament/Parliamentary_Departments/Parliamentary_Library/pubs/BriefingBook44p/Marriage

Pawson, Ray (2006). Evidence-based policy: a realist perspective. London: Sage.

Peters, B. Guy (2005). Policy instruments and policy capacity. In Martin Painter and Jon Pierre, eds. Challenges in state policy capacity: global trends and comparative perspectives, 73–91. Basingstoke, UK; New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Porter, Michael E. (1985). Competitive advantage: creating and sustaining superior performance. New York: The Free Press.

Rhodes, R.A.W. (2016). Recovering the craft of public administration. Public Administration Review (July/August): 638–47. DOI: 10.1111/puar.12504

Sabatier, Paul A. (2013). Toward better theories of the policy process. PS: Political Science and Politics 24(2): 147–56. DOI: 10.2307/419923

Sanderson, Ian (2002). Evaluation, policy learning and evidence-based policy making. Public Administration 80(1): 1–22. DOI: 10.1111/1467-9299.00292

Scott, Claudia Devita, and Karen J. Baehler (2010). Adding value to policy analysis and advice. Sydney: UNSW Press.

Stewart, Jenny, and Wendy Jarvie (2015). Haven’t we been this way before? Evaluation and the impediments to policy learning. Australian Journal of Public Administration 74(2): 114–27. DOI: 10.1111/1467-8500.12140

van Heffen, Oscar, and Pieter-Jan Klok (2000). Institutionalism: state models and policy processes. In Oscar van Heffen, Walter J.M. Kickert and Jacques J.A. Thomassen, eds. Governance in modern society: effects, change and formation of government institutions, 153–77. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands.

About the authors

Dr John R. Butcher has adjunct appointments as an Australian and New Zealand School of Government (ANZSOG) Research Fellow in the School of Politics and International Relations at the Australian National University and as a research fellow in the John Curtin Institute of Public Policy within the Curtin Business School at Curtin University. His principal research focuses on the relationship between government and the not-for-profit sector. He is the co-editor (with David Gilchrist) of The three sector solution (2016) and co-author (with John Wanna and Ben Freyens) of Policy in action (2010).

Trish Mercer is an ANZSOG Visiting Fellow at the Australian National University and a regular presenter in the Crawford School’s Executive Education Program. Trish has a doctorate in history from ANU and a diploma in American studies from Smith College (USA). As a former senior executive in the Australian public service, Trish had a diverse career incorporating policy and program development, research and evaluation, and direct service delivery. Her social policy research interests include early childhood, schools and employment services. Her current ANZSOG research project explores how theories of the policy process can be transferred and taken into practice.

- Butcher, John R., and Trish Mercer (2024). Making public policy. In Nicholas Barry, Alan Fenna, Zareh Ghazarian, Yvonne Haigh and Diana Perche, eds. Australian politics and policy: 2024. Sydney: Sydney University Press. DOI: 10.30722/sup.9781743329542. ↵

- Neilsen 2012. ↵

- Murray–Darling Basin Royal Commission 2019, 63. ↵

- Citing famous quotes can be messy too; a similar remark is frequently misattributed to the 19th-century German statesman, Otto von Bismarck. ↵

- Kingdon 1995. ↵

- John 2012, 12. ↵

- Linder and Peters 1990; van Heffen and Klok 2000. ↵

- Dowding 1995; Howlett, Mukherjee and Koppenjan 2017; Sabatier 2013. ↵

- Howlett 2009; Howlett and Cashore 2009. ↵

- Hall and Taylor 1996; Hill 2014. ↵

- Braun and Busch 1999; John 2003. ↵

- Davies and Nutley 2000; Pawson 2006. ↵

- Marmot 2004; Sanderson 2002. ↵

- Howlett and Migone 2013. ↵

- Banks 2018; Stewart and Jarvie 2015. ↵

- Adams, Colebatch and Walker 2015, 104; Rhodes 2016, 638. ↵

- See Katsonis 2019. ↵

- Cairney 2015, 23; Maddison and Denniss 2009, 82. ↵

- Lindblom 2018. ↵

- Cairney 2015, 17. ↵

- Cairney 2015, 31. ↵

- Althaus, Bridgman and Davis 2018. ↵

- Althaus, Bridgman and Davis 2018, 45. ↵

- Bridgman and Davis 2003, 102. ↵

- Howlett, McConnell and Perl 2017; Maddison and Denniss 2013, 87–89; Scott and Baehler 2010, 29. ↵

- Adams, Colebatch and Walker 2015, 108; Colebatch 2006, 26; Gill and Colebatch 2006, 261–2; Head and Crowley 2015, 4. ↵

- Althaus, Bridgman and Davis 2015, 112. ↵

- Porter 1985. ↵

- Althaus, Bridgman and Davis 2018. ↵

- Peters 2005. ↵