48 Intergovernmental coordination

Christopher Walker and Jason O’Neil

Key terms/names

Aboriginal community controlled health organisation (ACCHO), complexity of government, federalism, First Nations and First Peoples, Indigenous public health policy, intergovernmental relations, multi-level governance (MLG), National Water Grid Authority, Ngarrindjeri Regional Authority, policy coordination, self-determination, vertical and horizontal divisions of power, Walgett Aboriginal Medical Service, water infrastructure

Introduction

In this chapter[1] we explore the intergovernmental context of Australian public policy and how this impacts the coordination and delivery of public policy efforts across agencies and levels of government. ‘Intergovernmental’ refers to the areas of overlap and engagement between all levels of government. In an Australian context, this means the interaction between federal government, state and local governments and their overlapping policy priorities.[2] We are particularly interested in the influence of federalism, which is the formal division of government power between national and subnational governments, which characterises the governing framework in Australia and other countries such as Canada and the United States.[3] The Australian federal structure of government was initially designed to give clarity to the divisions of power and responsibility between the national and state levels of government. This division is spelt out in the Australian Constitution. But in practice the governing mechanisms through which each level of government pursues the design and delivery of public policy is incredibly messy and complicated.[4]

Over time the development of the Australian federal system of government has seen the emergence of a range of mechanisms (mostly fiscal) through which the national government becomes involved in the policy and service delivery work of the states and territories. Similarly, states and territories periodically make claims that in certain policy areas the fiscal strength of the national government requires their support and intervention. This has been a common call from the states and many affected communities during natural disasters, and was also a regular source of contention throughout the first two years of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020–21.

Achieving policy coherence and ensuring services are delivered in a way that drives effective policy outcomes will very often require both an understanding of the complexity of the intergovernmental context as well as significant effort in intergovernmental policy coordination. This chapter considers what students of public policy need to know to be effective in policy work within the Australian federal context and raises the importance of engaging with a multi-level governance approach to policy coordination. At its most basic definition, multi-level governance (MLG) refers to the distribution of power and jurisdiction over a set territory. Later in this chapter we discuss how MLG theory encourages us to consider the ‘horizontal’ divisions of power outside the more traditional top-down hierarchical approach to governing.

We argue that a broader, more expansive view that considers policy work within an MLG framework allows other participants and authority structures that might influence policy (beyond the boundaries of formal intergovernmental structures) to be identified and engaged within the policy-making process. Power and authority are increasingly dispersed across states, markets and civil society, and effective policy work needs to account for and engage with these spheres of influence.

After this introduction, this chapter considers how federal systems influence policy and program development across levels of government, with reference to how the National Water Grid Authority makes use of some of the more typical structures and instruments of intergovernmental policy coordination. Our discussion then moves to give broader consideration of MLG before moving to the analysis of the Ngarrindjeri Regional Authority and Walgett Aboriginal Medical Service as cases that illustrate the experiences of First Nations. We explore these cases and point to the role of First Nations and the avenues such representatives have for policy participation and decision making in an MLG context. A supplementary argument of this chapter is how policy work within an intergovernmental context can be built on and extended to strengthen opportunities for voice, participation, and self-determination of First Nations communities. The examples in this chapter highlight that policy coordination and intergovernmental decision making continue to evolve and need to adapt to the changing demands, voices, and expectations of our diverse communities.

How federal systems influence policy: intergovernmental structures and instruments

Fenna notes that, despite the constitutional division of powers between the federal and state governments, there is no guarantee that each level of government respects the other’s jurisdiction.[5] The Commonwealth has often used its financial advantage to become involved in areas that are generally considered areas of state responsibility. Health and education are the clearest examples, but there are a range of areas where the Commonwealth allocates financial grants to the states with conditions that influence policy orientation and service priorities. The vertical fiscal imbalance in the Australian federal system (that is, the Commonwealth has most of the funds and the states have most of the service delivery responsibilities without sufficient resources to fund them) creates a vast array of intergovernmental forums, negotiations and mechanisms of liaison that characterise policy arenas. It is universally accepted that policy is a contested process,[6] and this contestation and the development that occurs within an intergovernmental context are particularly important in shaping the Australian public policy process.

A sophisticated and complex infrastructure of ministerial councils, intergovernmental committees, working groups and agreements has developed over time that underpins and drives processes of policy development, endorsement and coordination between levels of government. Major government departments located within federal and state governments have dedicated policy units and policy specialists whose primary role is to manage, coordinate and strategise intergovernmental relations. There are intergovernmental policy experts in each state and Commonwealth department who regularly engage in meetings, forums and working parties to map out how the participation of each level of government might be exercised around a particular policy challenge. The Commonwealth and the states also have an interest in mobilising outside actors to help ensure the successful implementation of new policies and programs. A range of organised (and not so organised) individuals and groups from business, the community, professions, trades and other civil society interests share a concern for how policy might affect their livelihoods, local environments and general living conditions. A major challenge for intergovernmental policy work is how these interests are brought into (or kept out of) the policy development process.

Fenna notes the tensions that arise when levels of government hold conflicting policy priorities, citing transport (road infrastructure has been favoured by the Commonwealth and public transport favoured by the states) and climate change as examples.[7] When national funding seeks to drive a specific preference for policy action, the intergovernmental mechanisms of public agencies (as described above) become active in trying to reach agreement on pathways for implementation. This tends to concern the definition of priorities, how money will be spent and how progress and achievements will be reported. Here we see how policy development appears to be driven from a top-down (Commonwealth to states) perspective.[8] In these circumstances, policy development is seen as the exercise of authority down the vertical dimension, where the fiscal power of the Commonwealth formally directs discussions with the states and defines the parameters for exploring policy options. In many of these discussions, the states are beholden to national priorities and preferences. This vertical understanding of policy processes maps well with what is observed in practice. But the contested nature of policy also points to the effort made by forces on the horizontal dimension (those actors outside government) that seek to have a role in policy development and implementation. This is where policy development in an intergovernmental context may become incredibly complex and the simplistic view of the Commonwealth merely directing states on policy priorities and preferences is not a complete account of what happens in practice.

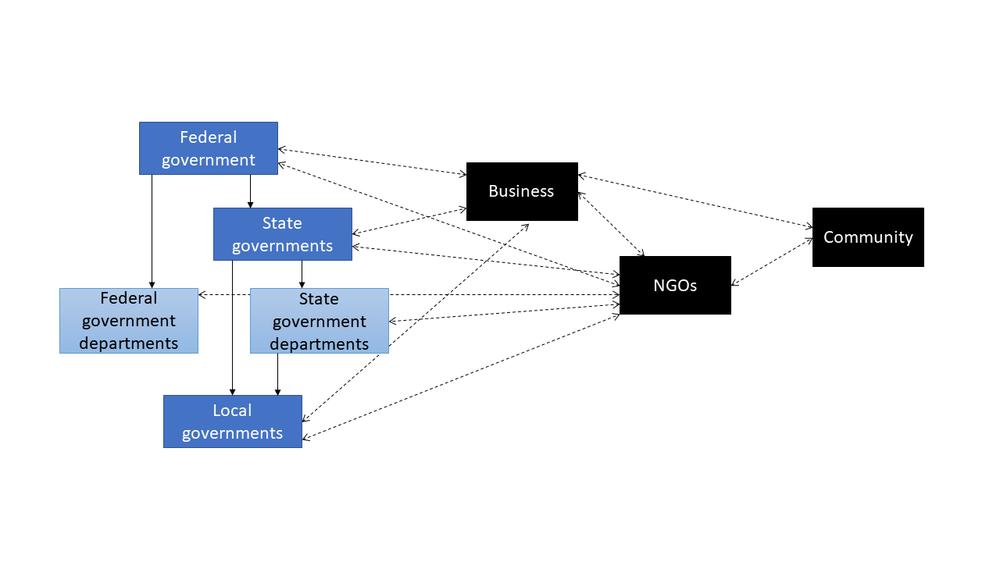

Figure 1 is a simplified illustration showing the traditional ‘vertical’ dimension of power between governments on the left, with non-government actors along the ‘horizontal’ dimension of power to the right. To illustrate this further, the following case study discusses how Commonwealth funding for major water infrastructure projects is negotiated and managed with the states; aspects of the case that align with the concepts of vertical and horizontal dimensions of policy interaction are highlighted.

National Water Grid Authority

The National Water Grid Authority (NWGA) was established by the federal government in 2019 to collaborate with the states and territory governments in the funding and development of water infrastructure projects. The provision of water infrastructure and water security is a state responsibility. The agreement that underpins the NWGA provides an avenue for the Commonwealth to direct funding to projects in all states and territories.

The Commonwealth government reported a contribution of $1.1 billion to the National Water Grid in the 2022–23 budget.[9] While the Commonwealth is committed to fund a minimum of 50 per cent of the cost of water projects, the process of policy development and project approval requires the navigation of a complex system of intergovernmental agreements, committees and administrative compliance.

The policy and funding framework is governed by a series of intergovernmental agreements. This includes the National Partnership for the National Water Infrastructure Development Fund as well as schedules under the Federation Funding Agreements on Infrastructure and Environment. These agreements specify levels of funding and the division of roles and responsibilities of each level of government. All states and territories and the Commonwealth have signed up to these agreements. The execution of the agreements is supported by administrative systems and the work of the NWGA.

The NWGA publishes a program administration manual (National Water Grid Authority 2022) outlining the requirements for state and territory water infrastructure projects to be considered under the national water infrastructure fund. It is in these lower-level policy documents that more evidence of Commonwealth policy priorities emerges; these priorities include specific requirements once projects reach certain thresholds.[10] For example, any project seeking funding under the agreement that is valued at or over $7.5 million must include an Indigenous Participation Plan that sets out ‘the anticipated opportunities for Indigenous participation, including specific targets for Indigenous employment and supplier-use in the delivery of projects’. An independent advisory body to the NWGA also provides economic, agricultural, and environmental and water science advice. The advisory body also has responsibility to represent and liaise with community interests on water infrastructure matters.[11] This means state submissions for project funding are likely to be subject to further scrutiny and analysis before being assessed and considered by the NWGA.

The design, development, and nomination of any water infrastructure project under this national program would also require a complex array of work across multiple state departments and assessment against local and regional planning rules. It is likely that state projects considered under the intergovernmental framework would be managed centrally by a coordinating agency such as state departments of treasury or premier and cabinet. This way, state compliance with the funding, policy and reporting requirements of the national framework can be assured, and the submission of funding bids that require 50 per cent matched funding from the state can be incorporated into state budgeting processes (an important role for state Treasury).

The National Water Grid Authority case study highlights how the national government draws on its fiscal power to influence state policy and infrastructure priorities. The hierarchical arrangement between state and Commonwealth authorities described in this case study also interacts with formal horizontal policy structures that have input to water infrastructure approval processes, as illustrated in Figure 1.

Without going into the detail of how non-government actors might interact with the policy development and implementation processes, we can see that intergovernmental policy work adds significant complexity to what many might consider mainstream policy work. Where a state decides to move one of its water infrastructure projects into the national framework (enabling the state to access shared funding rather than fully fund the project from its own resources), another layer of administrative and approval processes is added to the project. The greater the number of projects a state nominates under this funding scheme, the more significant the level of influence the Commonwealth exercises over state government water infrastructure policy and capital development.

Understanding and navigating the complexities of bureaucratic policy processes through systems of state and Commonwealth departments remain challenging and complex tasks for public servants, hence the need for departments to establish work units and staff roles that specialise in this intergovernmental work. But understanding and seeking to influence the complex structure of committees, administrative systems, implementation plans and working parties becomes an even greater challenge for external stakeholders who wish to participate and exercise their voices in this unique policy development process. So, while cooperative and collaborative effort may characterise the interest of those who want to see federal policy systems operate more effectively and efficiently, engagement in these processes remains difficult, resource intensive and in many instances a time-consuming and lengthy process for those outside government.

For many non-government actors, they remain significantly dependent on the policy development and engagement practices of state and Commonwealth departments as the primary avenue through which they might have influence and a voice in the process. For example, as the administrative rules of the National Water Grid Authority specify, mandatory evidence of engagement, planning and project involvement of non-government groups is required of projects that reach certain funding thresholds.

The complexity of intergovernmental policy processes is often criticised as an opaque, secretive and an exclusive process.[12] Agreements may often result in policy decisions and services that overlap with existing services already in place. These inefficient and duplicated outcomes may reflect the inability of policy practitioners to reach agreement on key issues across levels of government. This is often driven by the political and ideological differences of the respective governments to which agencies at each level must report. For example, citing the National Water Grid Authority case study, some states may already have in place regional water infrastructure plans with identified funding, yet states still sign up to the national agreement because it provides an avenue for accessing supplementary funding from the national government in a policy area that has traditionally been a state responsibility. But Commonwealth priorities (for example, agricultural water projects) may skew and disrupt state priorities (for example, sustainable water supply to population centres). Here the policy outcome tends to reflect what could be agreed amongst the parties rather than what might be the most sensible and rational policy outcome. This illustrates how intergovernmental policy is often shaped by political expediency.

Nevertheless, federal systems do promote policy innovation and the sharing of ideas. A strength of intergovernmental policy forums is that participating governments bring to the table a diversity of ideas, understandings of the problem and often unique experiences and approaches for resolving policy challenges. It is important to note that policy processes extend beyond the formal authority of levels of government and agency structures that shape intergovernmental relations. The national water infrastructure example alludes to the diversity of actors outside government who are likely to have an interest and be engaged in any significant project proposal under the national framework. As noted in our Introduction, we claim that the increasing complexity of contemporary Australian policy making is not effectively captured by a simplistic analysis of Commonwealth and state intergovernmental work.

The following discussion briefly explores how we use the term ‘multi-level governance’. We see MLG both as an important analytical lens for understanding policy action but also as an effective guide for structuring policy work that engages stakeholders, markets and authority both horizontally and vertically. We then discuss another applied example of intergovernmental policy work, which we will argue is better understood and actioned through the frame of MLG.[13]

Multi-level governance

MLG at its most basic definition describes political and policy systems that divide power and jurisdiction over a territory. The academic literature defines two distinct types of MLG.[14] Type I MLG is where power and authority is distributed across a set number of jurisdictions that are stable and don’t change over time. This type aligns well with the formal federal system of government discussed in this chapter.[15] Type II MLG is more fluid and aligns with the understanding we want to introduce as central to effective policy work.

Under Type II MLG there is potential for multiple overlapping jurisdictions, as well as formal and informal collaborations between government and non-government actors. This form of MLG accounts for the influence of actors from markets, civil society and non-government organisations, and considers how governance might be structured by the informal and non-hierarchical interactions that occur beyond the structures of government.[16] Type II MLG is more likely to be a temporary (or ongoing) collaboration for a particular policy or governance purpose.

As a tool to help us understand policy systems, MLG can go further than the ‘vertical’ division of power between federal and state governments, and the institutions and agreements that might shape intergovernmental policy making.[17] While studies of federalism encourage us to consider the formal institutions of law and policy on this vertical axis, MLG encourages us to also consider horizontal collaborations, sub-levels of governance including regional bodies and local governments.[18]

MLG shows us that policy coordination can and often does happen in more discrete, informal ways, particularly at the local or regional level. For example, in South Australia, the Ngarrindjeri Regional Authority is a representative body for the peoples of the Ngarrindjeri Nation, centred around the lakes of the Murray River, south-east of Adelaide. In 2009, the Ngarrindjeri Regional Authority entered into an agreement with the South Australian government, formalising in contract law several requirements for the state government to consult with the Ngarrindjeri Regional Authority on natural and cultural resource matters.[19] The regional authority also developed similar agreements with local councils to ensure that Ngarrindjeri people are involved in local planning and environmental assessments. By formalising requirements to consult with the authority on cultural heritage matters, the Ngarrindjeri Nation can collaborate with multiple government departments to protect the health of Ngarrindjeri Country and cultural heritage. The Ngarrindjeri Nation has worked to incorporate their approach to self-governance into the formal Australian federal governance structures, and while most effective in capturing engagement along the vertical interactions of state and local governments, this arrangement also extends to any forms of policy intervention from the national government that might impact within their Country.

This example highlights how further layers of governance, and the active engagement of these representative bodies in policy development and coordination processes, adds complexity but also brings value and relevance of such work for particular communities. Here we see how MLG structures can be organised and engaged in policy processes that increase First Nations self-determination. The following case study of Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisations (ACCHOs) aims to illustrate in further detail the policy benefits of an MLG approach.

Walgett Aboriginal Medical Service, ACCHOs and COVID-19

Walgett Aboriginal Medical Service (WAMS) is an Aboriginal community-controlled health organisation (ACCHO) on Gamilaraay Country in northern New South Wales. Founded in 1986, WAMS has provided primary health care to Walgett and surrounds for more than 30 years. Through funding from two Commonwealth departments and three state-level organisations, WAMS operates a dental clinic, vaccination clinic, chronic diseases clinic, general practitioner clinic, a community hall and garden, a midwifery program and a medication dispensary. In 2016, WAMS employed more than 100 people (including visiting specialists), and 60 per cent of its clients were First Nations people.

As an ACCHO in a remote country town, WAMS operates at the nexus of intergovernmental policy making, working with both federal and state governments to offer primary health care to surrounding communities. Like all ACCHOs, WAMS is governed by an elected board that represents the community’s interests. ACCHOs are themselves represented at the state and territory level by eight peak bodies. These state-level bodies are ‘affiliates’ of the national peak body, the National Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisation (NACCHO). Across Australia, 144 ACCHOs are members of NACCHO.

Public health crises, like the COVID-19 pandemic, highlight the complexity and scale of these structures and the importance of organisations like WAMS and their engagement through MLG systems in the development of public policy responses. As the COVID-19 pandemic developed, clarification of the roles and responsibilities of each level of government became a focus of analysis and concern. At the formal governmental level, it was clear that the federal government was responsible for the purchase and distribution of vaccinations (including to state governments) and the states were responsible for public health orders and the general health response to COVID-19. In communities like Walgett, ACCHOs were on the frontline of COVID-19 care and public health response, engaging with a diversity of local organisations outside the formal structures of government (horizontal dimensions of policy influence and power).

In March 2020, WAMS joined the federal government’s General Practitioner Respiratory Clinic program, to receive specialised equipment and training to screen Walgett community members for COVID-19 and care for positive cases. In March 2021, WAMS began vaccinating community members with the AstraZeneca vaccine, while strongly advocating to federal and state governments for increased supply of vaccinations, particularly of Pfizer vaccines that were in high demand from the community. On 10 August 2021, the New South Wales state government put Walgett and other communities, including Bourke and Brewarrina, in the state Western Local Health District into a seven-day lockdown after a positive case of the Delta COVID-19 variant was active in the region. At the time, only 8 per cent of Aboriginal people in north-western New South Wales had been fully vaccinated, increasing pressure on WAMS to continue delivering COVID-19 testing and vaccinations to Walgett and surrounding towns and villages in the Walgett Shire. As more Walgett families went into COVID isolation, WAMS engaged with a diversity of local organisations and assisted with the distribution of food, medicines, and other essential supplies directly to people’s homes.

Throughout the pandemic, WAMS and the network of ACCHOs across Australia have been essential to an effective public health response to COVID-19. Many of these services became the delivery point for both national and state health responsibilities. WAMS has continually advocated to both the federal and state governments to meet the needs of the Walgett community. This illustrates how small local actors find themselves navigating complex arrangements of Commonwealth and state responsibilities and concurrently draw on their own network of connections through other MLG structures.

As the Walgett Aboriginal Medical Service case study shows, the capacity to both navigate and draw on the expertise and resources available through these overlapping governance frameworks has helped strengthen policy responses and achieve better policy outcomes for local communities. By 2022, the vaccination rate in the Walgett Shire was over 90 per cent, exceeding the rate for some Sydney metropolitan areas that have higher levels of access to government health services.[20] This case highlights the importance for policy makers to be aware of systems through which they can engage the expertise of First Nations community-controlled organisations and develop collaborative approaches on how best to achieve shared policy outcomes in First Nations communities.

First Nations policy making and MLG

Indigenous policy is a significant arena with stakeholders actively interacting at every level of government and representing a diversity of local and regional policy priorities. Indigenous policy is also an area where government priorities have shifted dramatically over the decades.[21] Since at least 2016 there has been a renewed receptiveness by federal, state and territory governments to increased self-determination, co-design and consultation on policies that affect First Nations communities. This shift in politics and policy is most clearly demonstrated by the treaty processes (of varying success and design) in Victoria, South Australia, the Northern Territory and Queensland, and the Albanese Labor government’s 2022 commitment to holding a referendum on the First Nations Voice and implementing the Uluru Statement from the Heart. These shifts in attitude from Australian governments demonstrate the enduring relevance and importance of First Nations as policy actors and polities with their own interests and priorities. It also demonstrates the need for policy makers to be aware of First Nations policy priorities and the importance of genuine self-determination in the policy process.

In this final section we aim to briefly bring together our analysis of policy coordination within an MLG context and the role of First Nations (as distinct political communities with the right to self-rule) in policy making. Our objective is to highlight the challenges and opportunities that federalism and MLG create for First Nations peoples to pursue their own policy priorities.

First Peoples assert both peoplehood and nationhood as an expression of their sovereignty and right to self-determination. This raises important questions for policy makers, and the Australian public, about how to make room for Indigenous influence and control within the systems of democracy and policy making by federal and state governments. Our examples above have shown that this happens in different forms. The Ngarrindjeri Regional Authority and its agreements with state and local governments is a formalised process that brings in First Nations people as a partner in policy-making processes. The example of WAMS shows that some policy arenas, such as health, have incredibly complex state and federal structures with multiple avenues for Indigenous voice and influence in policies. The case also illustrates how national and state policy implementation can vary significantly at the local level, as available resources and horizontal features such as actor networks and local circumstances reshape action on the ground.

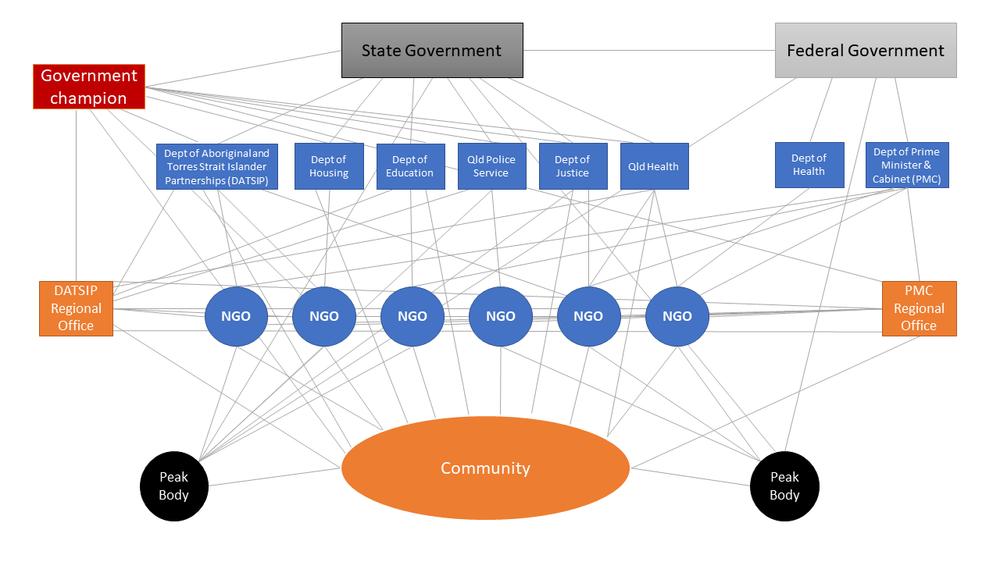

MLG, as a method for allowing greater collaboration and policy coordination across both vertical and horizontal distributions of power, presents an opportunity for policy makers to increase genuine partnership, collaboration and deference of decision making to First Nations. Over 2016–17, the Queensland Productivity Commission conducted an inquiry into ‘service delivery in remote and discrete Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities’ across 19 communities in Queensland. This inquiry identified a ‘bureaucratic maze’ of service delivery and funding schemes that obscured accountability, diminished community control and ultimately hampered policy outcomes despite over $1.2 billion in estimated funding for hundreds of initiatives servicing just over 40,000 people.[22] The bureaucratic maze illustrated in Figure 2 demonstrates much of the difficulty for First Nations peoples to pursue their own policy goals and objectives, which may not measure wellbeing or success in the same terms or the same timelines as the government does.

The Queensland Productivity Commission’s inquiry recommended a significant ‘reform package’ that emphasised the need for the Queensland government to transfer decision making and accountability for service delivery directly to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities through formal agreements with community-owned authorising bodies.[23] The inquiry also emphasised the importance of longer-term funding and service models to allow service delivery to break out of the short-term cycles and focus on holistic community need outside discrete policy silos.[24]

While the complications and challenges described by the Queensland Productivity Commission might be described as a failure of effective policy coordination, the inquiry does demonstrate the great potential for MLG approaches. First Nations governance, and the ways that First Nations peoples exercise their rights to self-determination as communities of people, is relevant to policy making because policy is ultimately an expression of the priorities of government. First Nations, as governments or sources of political authority and will, have their own priorities for their own communities.

In this context MLG, can work to improve policy outcomes by engaging with First Nations communities as policy actors and partners, as well as beneficiaries and recipients. The cross-cutting nature of Indigenous affairs and the focus of First Nations organisations and communities on holistic wellbeing across policy spheres make First Nations policy and First Nations governance the frontline of policy coordination. Under an MLG approach, there exists great potential for First Nations control over decision making along both the vertical and horizontal axes where action is relevant in achieving better policy and service outcomes for communities.

Conclusion

In this chapter, we have discussed the challenges and opportunities for policy makers in federal, state and territory governments to coordinate policy outcomes and processes across the predominantly vertical lines of federalism. We have emphasised the importance of understanding how formal structures of federalism and the influence of fiscal imbalance shape the policy process in Australia. This has been illustrated with a contemporary case on the intergovernmental funding and administration of water infrastructure projects. We have also discussed the concept of MLG, and the potential for increased coordination across horizonal lines that connect diverse sources of power, influence and resources.

An awareness of these structural forces, and a concerted effort to work along both the horizontal and vertical divisions of power with government and non-government actors will assist policy practitioners in their pursuit of improved policy outcomes. This is particularly true in areas of Indigenous policy.

Our examples illustrate how both Australian governments and First Nations can more effectively progress shared policy objectives in a system that extends intergovernmental relations into a broader MLG environment. This can be achieved by extending and building on the formal federal structures already in place that have traditionally dominated policy practice. Such an approach to Indigenous policy devolves greater self-determination and decision-making power to First Nations.

We believe that the complexity of policy coordination within an MLG system creates opportunities for experimentalism, innovation and more effective implementation. Strengthening policy development and engagement through MLG frameworks will help ensure more positive outcomes for individuals and affected communities.

References

ABC News (2021). Check the COVID vaccination rate in your NSW postcode. Accessed 29 October 2022. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2021-08-18/nsw-covid-19-vaccination-map/100387416

Althaus, Catherine, Peter Bridgman and Glyn Davis (2018). The Australian policy handbook: a practical guide to the policy making process. 6th edn. Sydney: Allen & Unwin.

Cairney, Paul (2012). Understanding public policy: theories and issues. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Colebatch, Hal K. (2009). Policy. Buckingham, UK: Open University Press.

Coleman, Jo (2021). WAMS changing the way we do business. Aboriginal Health & Medical Research Council of NS., 27 May. https://www.ahmrc.org.au/wams-changing-the-way-we-do-business/

Daniell, Katherine A. and Adrian Kay (2017). Multi-level governance: an introduction. In Katherine A. Daniell and Adrian Kay, eds. Multi-level governance: conceptual challenges and case studies from Australia. Canberra: Australian National University Press. DOI: 10.22459/MG.11.2017

Fawcett, Paul and David Marsh (2017). Rethinking federalism: network governance, multi-level governance and Australian politics. In Katherine A. Daniell and Adrian Kay, eds. Multi-level governance: conceptual challenges and case studies from Australia. Canberra: Australian National University Press. DOI: 10.22459/MG.11.2017

Government of South Australia and Ngarrindjeri Regional Authority (2016). Kungun Ngarrindjeri Yunnan agreement: listening to Ngarrindjeri People talking: KNYA Taskforce terms of reference 2016. https://data.environment.sa.gov.au/Content/Publications/KNYA%20Taskforce%20Terms%20of%20Reference.pdf

Hooghe, Liesbet and Gary Marks (2001). Multi-level Governance and European Integration. Oxford: Rowman & Littlefield.

National Water Grid Authority (2021). National Water Grid Advisory Body charter. https://www.nationalwatergrid.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/NWG-Advisory-Body-Charter.pdf

—— (2022a). October Budget 2022-23: More than $1.1 billion toward water security. Accessed 29 October 2022. https://www.nationalwatergrid.gov.au/about/news/october-budget-2022-23-more-11-billion-toward-water-security

—— (2022b). Program administration manual: National Water Grid Fund. Canberra: Department of Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development and Communications. https://www.nationalwatergrid.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/NWGF-Program-Administration-Manual-April-2022.pdf

Queensland Productivity Commission (2017). Final Report: Service delivery in remote and discrete Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities. https://s3.treasury.qld.gov.au/files/Service-delivery-Final-Report.pdf

About the authors

Jason O’Neil is Lecturer and Director of Indigenous Legal Education in the UNSW Faculty of Law & Justice, and a young Wiradjuri man from Central West NSW. His PhD research focuses on Indigenous self-determination and centring First Nations in Australian public policy.

Christopher Walker is the Deputy Dean (University Relations) and Academic Director of the Executive Master of Public Administration (EMPA) at the Australia and New Zealand School of Government (ANZSOG). He is also an Adjunct Professor with the School of Government and International Relations, Griffith University, Queensland. His current research projects are concerned with the analysis of policy transfer using social network analysis, digital public services and digital regulation in the road transport sector (trucking).

- O’Neil, Jason and Christopher Walker (2024). Intergovernmental coordination. In Nicholas Barry, Alan Fenna, Zareh Ghazarian, Yvonne Haigh and Diana Perche, eds. Australian politics and policy: 2024. Sydney: Sydney University Press. DOI: 10.30722/sup.9781743329542. ↵

- For a discussion of the influence of the intergovernmental context on Australian policy, see Althaus, Bridgman and Davis 2018, 104–5. ↵

- See chapter by Fenna on Commonwealth–state relations in this textbook. ↵

- See chapter by Fenna on Commonwealth–state relations in this textbook. ↵

- See chapter by Fenna on Commonwealth–state relations in this textbook. ↵

- Colebatch 2009. ↵

- See chapter by Fenna on Commonwealth–state relations in this textbook. ↵

- Colebatch 2009. ↵

- National Water Grid Authority 2022a. ↵

- National Water Grid Authority 2022b, 14–15. ↵

- National Water Grid Authority 2021. ↵

- Fawcett and March 2017, 67. ↵

- Daniell and Kay 2017, 11. ↵

- Hooghe and Marks 2001. ↵

- Daniell and Kay 2017, 3–4. ↵

- Bache and Flinders 2004, cited in Daniell and Kay 2017, 6. ↵

- Bache and Flinders 2004, cited in Daniell and Kay 2017, 6. ↵

- Cairney 2012, 166. ↵

- Government of South Australia and Ngarrindjeri Regional Authority 2016. ↵

- ABC News 2021. ↵

- For further discussion of this, see chapter by Perche and O’Neil in this textbook. ↵

- Queensland Productivity Commission 2017, i-xvi. ↵

- Queensland Productivity Commission 2017, xxviii–xxix. ↵

- Queensland Productivity Commission 2017, xxix. ↵