40 Immigration and multicultural policy

Andrew Parkin and Leonie Hardcastle

Key terms/names

asylum seekers, border protection, border security, environmental sustainability, ethnic communities, family immigration, humanitarian immigration, immigration, international students, multiculturalism, occupational immigration, population policy, temporary immigration, White Australia policy

Australia has been shaped by immigration.[1] Nearly half of today’s Australian population consists of immigrants born elsewhere or their first-generation descendants. As a consequence of its pattern of immigration, Australia is also a multicultural country. This chapter examines the policy evolution that has produced this situation. It also examines the distinctive political dynamics of the policy-making process pertaining to immigration and multiculturalism.

What’s at stake?

Immigration and multicultural policies directly shape Australia’s social composition and the social relations between and within its constituent communities. At the national level, the immigration policy settings mould the evolution of Australia’s overall ethnic character, an impact which can stir deep emotions. Over time, immigration numbers and the resultant multicultural transformation of the electorate have affected the nature of Australian political processes.

At the community level, immigration and multicultural policies shape and structure a potentially awkward social and political balance. On the one hand, there is a need to respect the multiple ethnic, cultural and religious identities with which Australians collectively now identify. On the other hand, harmonious and productive intercultural relations among Australians depend on some transcendence of these particularistic identities.

While it is shaping Australian society at its broadest levels, the implementation of immigration policy is also deeply personal for those affected. People’s life trajectories are potentially transformed by the decisions emerging from the administrative process established by the policy parameters.

Characteristics of this policy domain

Probably more than in most policy domains, an appreciation of the historical evolution of immigration policy is needed for a full understanding of the challenges and dilemmas characterising today’s policy debates.

Historical context

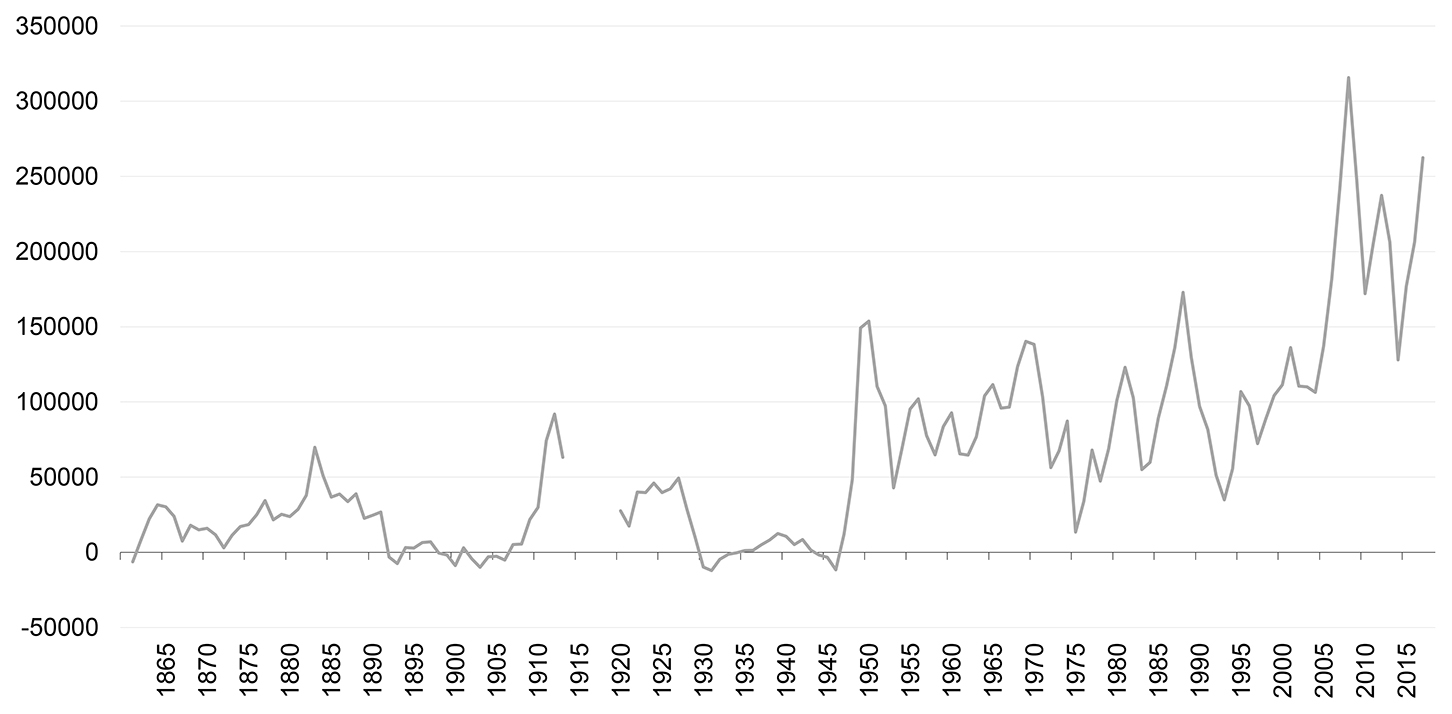

The history of Australian immigration policy implementation is embodied in the sequence of annual ‘net immigration’ numbers, encompassing more than a century and a half, reported in Figure 1. ‘Net immigration’ here means the number admitted to Australia each year less the number recorded as emigrating out of Australia in the same year.

Note: Different estimation methods may have applied at different times, so the chart is best understood as broadly indicative. The chart gap 1914–19 removes years where the data are distorted by the movement of service personnel associated with the First World War.

The sequence in Figure 1 begins in the early 1860s, a period when a ‘White Australia’ policy was becoming established. Until the late 1940s, periods of substantial net immigration were episodic and intermittent. These immigrants came almost entirely from the British Isles, including Ireland, and can be described in ethnic terms as Anglo-Celtic. They and their descendants overwhelmed the Indigenous population and established the basic political institutions and processes which Australia still features.

There were some exceptions to the Anglo-Celtic predominance (such as German and Italian immigrants) but the most notable perceived challenge was the arrival of a significant number of Chinese during the gold rushes of the 1850s. It was this challenge which led the Australian colonies, and from 1901 the new Australian government, to formalise the so-called White Australia policy. The policy precluded immigrants from Asia and later proscribed the continued use of indentured Pacific Islander labour. Various motivations explain why the White Australia policy was adopted; these include the protection of wages and working conditions from the potential impact of low-wage competition as well as a racist or ethnocentric distaste for population diversity.[2] The USA and Canada, likewise emerging in this period as prominent immigration-based ‘new world’ nations, adopted similar policies.

Significant change began in the late 1940s. The Chifley Labor government, followed by supportive Coalition governments thereafter, embarked on a mass immigration program that transformed Australia. The change instigated in the late 1940s is clearly visible in Figure 1 as an immigration surge that continues today. Britain was no longer the exclusive source; the new immigrants also came from a wide range of European countries, beginning with postwar refugees from eastern Europe, followed by substantial numbers from northern and later southern Europe (most notably, Italy and Greece). From the mid-1960s, the admission of small numbers from Asia signalled a quiet abandonment of the White Australia policy.[3]

The modern period

In 1973, the Whitlam Labor government formally discontinued the White Australia policy.[4] It also instituted a new domestic policy of multiculturalism which, overturning a rhetoric of assimilation which had accompanied the post-1940s ethnic diversification, celebrated Australia’s growing cultural diversity.

Immigration numbers surged again under the Fraser Coalition government from 1976. It was the Fraser government that elaborated the aspirational notion of multiculturalism into a range of policies supporting ethnic communities.

This period also saw the formalisation of the immigration policy regime which, in essence, still prevails today. It involves selection criteria which do not formally discriminate on the basis of race or national origin. It also involves three principal selection categories permitting immigrant admission on the basis of occupational skills (measured by a ‘points test’ scoring such factors as qualifications, English-language proficiency and age), family connections (mainly admitting the spouses, fiancées and dependent children of Australian residents) and humanitarian considerations (including refugees as narrowly defined under international conventions and others deemed in humanitarian need). This formally non-discriminatory and category-focused immigration system has now been in place in Australia for more than 40 years. The social impact of Australia’s immigration experience over the past 70 years has been transformative. The 2016 Census revealed that 26 per cent of Australians had been born elsewhere; 40 per cent of these immigrants had a national origin somewhere in Asia with 10 per cent originating in the Middle East or Africa.[5] Australia’s cultural transformation has been particularly dramatic in the major metropolitan areas, especially Sydney and Melbourne.

An immigration-driven transformation is also revealed in Australia’s religious profile. Whereas in the late 1940s nearly all Australians professed affiliation with some version of Christianity, the proportion identifying as Christians in the 2016 Census had fallen to just over half. While 30 per cent of Australians now profess no religious affiliation (another radical change from the late 1940s), around 8 per cent (and nearly a third of immigrants arriving over the past ten years) identify with non-Christian traditions.[6]

The immigration regime

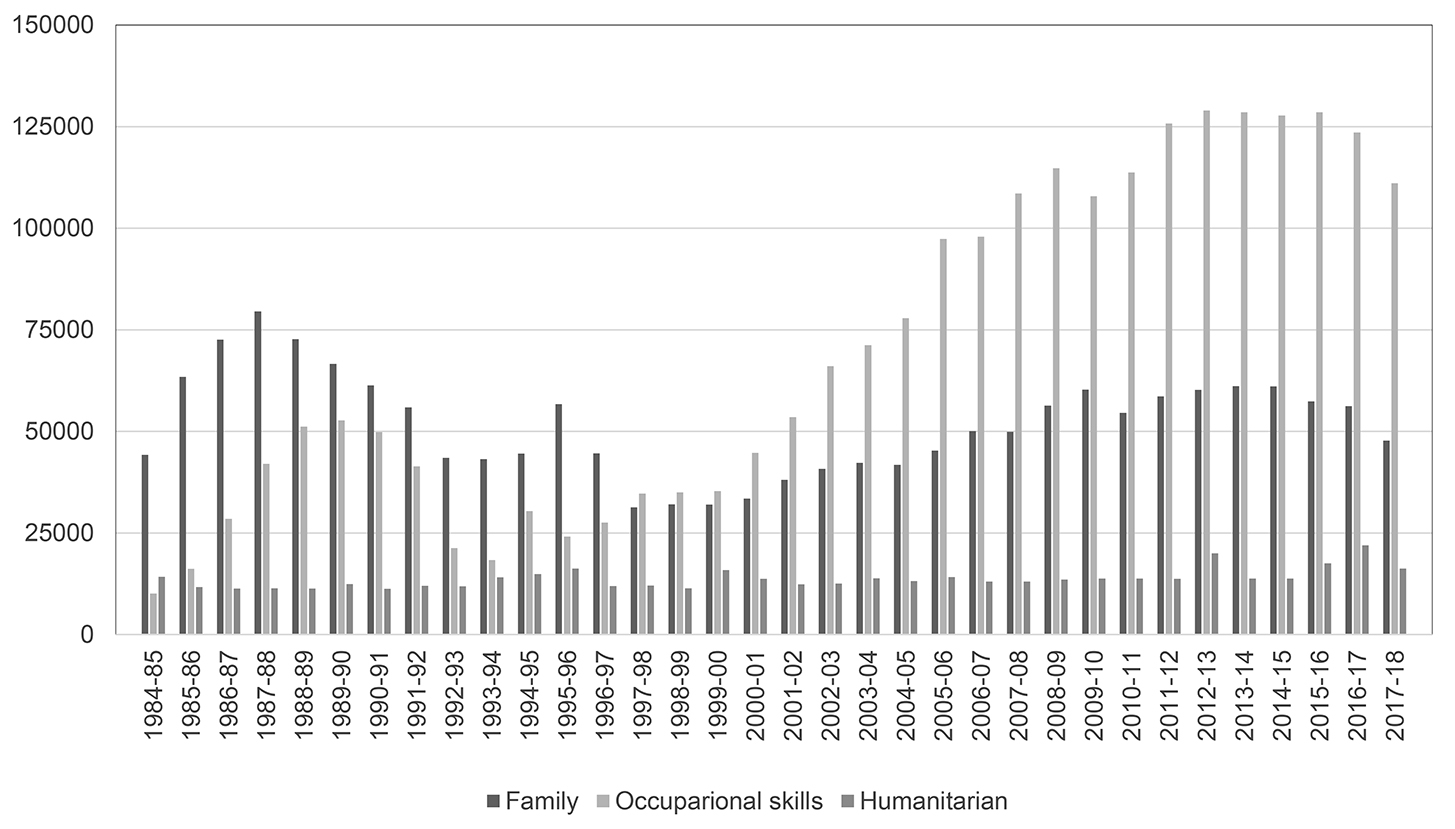

Figure 2 charts how categorical preferencing within the immigration program has played out over recent decades. It reveals that immigrants admitted on the basis of a family connection predominated during Labor’s lengthy period in office under the prime ministerships of Hawke (March 1983 to December 1991) and Keating (from then until March 1996). The Howard Coalition government, in office from March 1996, at first lifted the proportion admitted on the basis of occupational skills to about equal prominence as those with family connections. Then a decisive relative shift took place, preferencing applicants in the occupational-skills category. That decisive relative shift, consistent with a neoliberal policy emphasis on promoting economic growth and investment, has been maintained ever since. It survived the replacement of the Howard Coalition government by the Rudd–Gillard–Rudd Labor governments (December 2007 to September 2013) and has been maintained since then by the Abbott–Turnbull–Morrison Coalition governments.

Figure 2 also reveals the maintenance since the mid-1980s of a ‘humanitarian’ intake in the range of 11,000 to 20,000 per annum. The humanitarian program has two main components: an offshore component under which resettlement in Australia is offered to refugees and others with a humanitarian case located outside Australia, and an onshore component providing for claimants assessed to be refugees after arriving in Australia on a valid visa.

The humanitarian program looks relatively small in comparison to the family and occupational-skills categories, and over time represents a diminishing proportion of the total immigration intake. In comparison to other countries’ involvement in international efforts to resettle those stranded in refugee camps around the world, the Australian humanitarian program is one of the more generous.[7] However, this sound record contrasts markedly with the harsh regime applying to asylum seekers seeking to enter Australia and claim refugee status outside the parameters of the humanitarian program. This is despite the number of such claimants reaching Australia being relatively low compared with the numbers seeking to enter other target countries, for instance in Europe.

In the late 1970s, Australia’s acceptance of Indo-Chinese ‘boat people’ had signalled a decisive end to the old White Australia policy.[8] Over time, however, political tolerance for the management of undocumented asylum seekers arriving by sea waned, especially as it began to be associated with organised ‘people smuggling’ networks.

The Keating Labor government in 1992 initiated the mandatory detention of asylum seekers after facing a resumption of maritime arrivals largely driven by events in Cambodia. A new flow of arrivals (sourced mainly from Afghanistan, Iran and Iraq) began in the 1999–2000 period under the Howard Coalition government. Campaigning for re-election in 2001, Prime Minister Howard capitalised on his government’s refusal to accept a vessel, the Tampa, which had been diverted to Australia by asylum seekers. These asylum seekers were sent into detention, notably in Nauru and Papua New Guinea, instituting an offshore processing regime which has continued thereafter. The draconian approach did produce a virtual cessation of the maritime asylum-seeker arrivals.

After returning to government in December 2007, Labor under Prime Minister Rudd suspended the mandatory detention of maritime asylum seekers. Maritime arrivals (mainly Afghan, Iranian and Sri Lankan asylum seekers) later surged to unprecedented levels, including an extraordinary tally exceeding 25,000 arrivals in 2012–13. Many others tragically drowned at sea.[9] The Rudd and Gillard governments grappled with the cruel conundrum around what Prime Minister Rudd described as ‘our responsibility as a government … to ensure that we have a robust system of border security and orderly migration on the one hand as well as fulfilling our legal and compassionate obligations … on the other’.[10]

Eventually, Labor reintroduced mandatory offshore detention[11] but this did not stave off defeat in the September 2013 election to Coalition parties whose ‘stop the boats’ and ‘border protection’ rhetoric dominated the campaign. The incoming Abbott Coalition government matched that rhetoric with further policy action. It launched Operation Sovereign Borders[12] under which unauthorised boats were intercepted at sea and not permitted to enter Australian waters. Asylum-seeker maritime arrivals again virtually ceased under this regime which has continued through the succeeding Coalition governments headed by Turnbull (September 2015 to August 2018) and then Scott Morrison (from August 2018).

In early 2019, political attention turned to the management of the asylum seekers, numbering more than a thousand, who had been sent to the offshore locations of Nauru and Papua New Guinea’s Manus Island. An agreement with the USA allowed hundreds of these asylum seekers to be voluntarily transferred to the USA.[13] The Morrison government was forced, by a parliamentary majority in both houses comprising the Labor opposition, independent and minor-party MPs, to allow detainees certified as needing medical treatment to be treated in Australia.

Temporary immigration

The fraught politics around mainstream immigration and asylum seekers has perhaps obscured the significance of the substantial increase in what is termed ‘temporary immigration’.

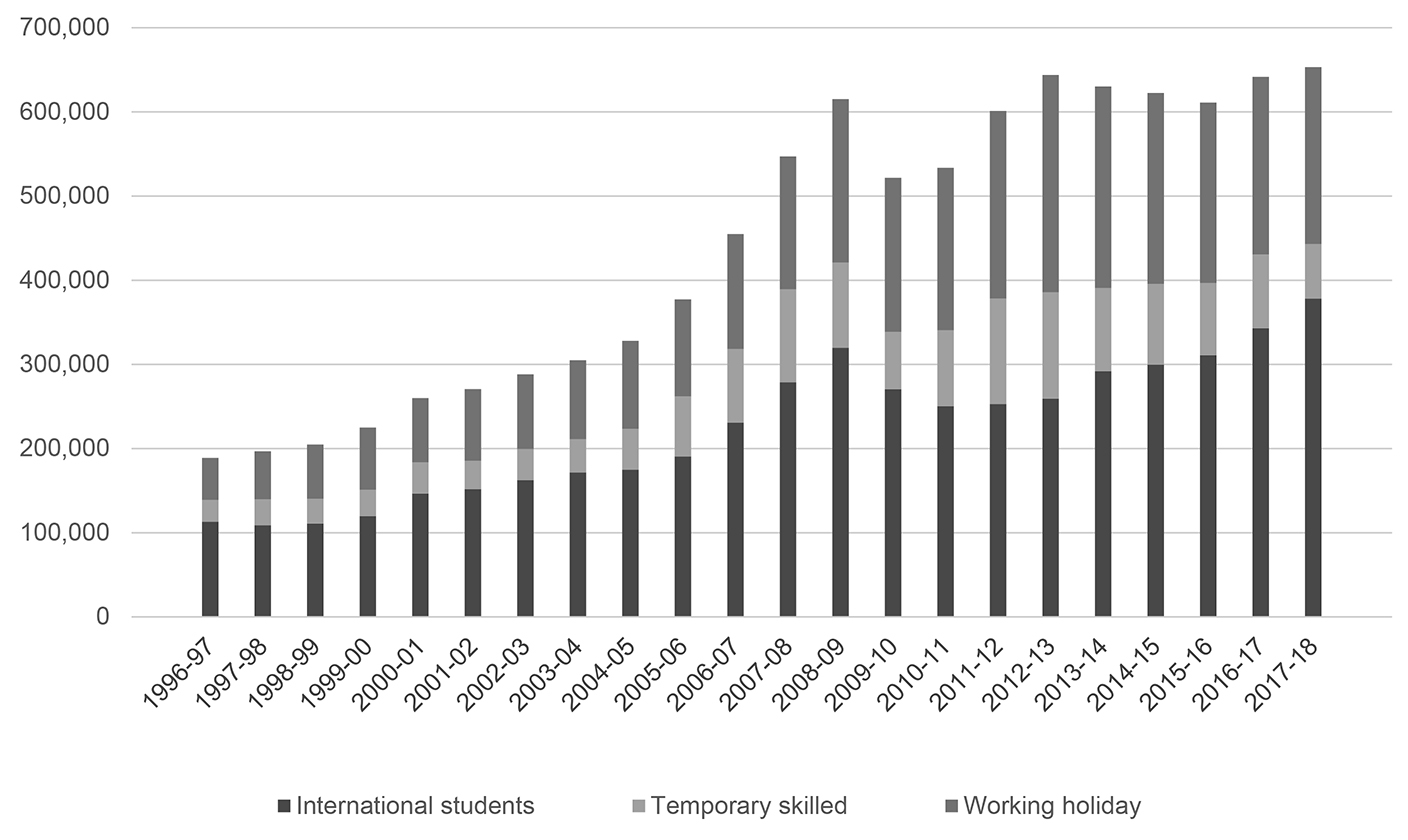

There are three principal categories of temporary immigrants, each of them carrying eligibility (under variable rules) to work in Australia:

- International students have become a prominent feature of the Australian education systems, most notably in the tertiary education sector. Some international students have post-study entitlements to remain temporarily in Australia for further work experience.

- Temporary skilled immigrants are admitted to work in what are supposed to be specific occupations or positions where employers find it difficult to recruit locals.

- Working holidaymakers are typically young adults permitted to undertake short-term paid work (such as seasonal work in regional horticulture).

Figure 3 shows the substantial, and increasing, scale of temporary immigration. Over the 20-year period since the late 1990s, temporary immigrant numbers have more than tripled. There is a connection between the temporary and permanent intakes, with a recent analysis finding that ‘about half of the permanent visas grants are to people who are already in Australia as temporary immigrants’.[14]

Temporary immigration has attracted some political controversy. Some critics are concerned about its claimed impact on the integrity of, and job competition within, the Australian labour market; they might be assured by a Productivity Commission finding that ‘recent immigration has had a negligible effect on the labour market outcomes of the local labour force’.[15] Many international students have evidently been exploited through underpayment of wage entitlements and poor working conditions.[16] An inquiry put in place by the Australian government has endorsed a finding that ‘as many as 50 per cent of temporary migrant workers may be being underpaid in their employment’.[17] Some critics are uncomfortable with temporary immigrants being treated in effect as ‘not quite Australian’.[18]

There have been claims that the temporary skilled program too readily overlooks the availability of qualified local recruits and/or permits an undesirable under-investment in the education and training that would support an upskilled local workforce.[19] Responding in part to such misgivings, the rules governing the temporary skilled program were significantly revised in April 2017, with the aim of ensuring, according to Prime Minister Turnbull, that ‘temporary migration visas are not a passport for foreigners to take up jobs that could and should be filled by Australians’.[20]

Multiculturalism

Immigration policies over the past few decades have mostly been characterised by a reasonably firm, though occasionally unsteady, bipartisan support from the two major party groupings of Labor and the Coalition. A similar combination of substantial consensus interspersed by occasional vacillation has characterised the ongoing acceptance of multiculturalism as the policy framework for managing Australia’s immigration-driven ethnic diversity.

There has long been some ambiguity about the degree to which multiculturalism has been intended to promote greater social cohesion and integration or for maintaining cultural diversity and empowering cultural minorities. In general, the bipartisan position has favoured social cohesion and integration.[21]

The Fraser Coalition government (December 1975–May 1983) set in place much of the national administrative and institutional infrastructure for multicultural policies. Under the Hawke Labor government in 1989, a National Agenda for a Multicultural Australia proposed three justifications for multiculturalism: its respect for cultural identity, its alignment with social justice and its utilitarian virtues in facilitating economic efficiency. Importantly, the document also specified ‘limits’ which, in effect, asserted the necessity for a set of common values within ‘an overriding and unifying commitment to Australia’.[22] This kind of careful specification of both the claimed virtues and necessary limits of Australian multiculturalism has enabled the concept to adapt and survive ever since.

Perhaps the most serious challenge took place during the period of the Howard Coalition government (1996–2007). The Howard government seemed to downplay the terminology of multiculturalism and emphasised instead terms like ‘social cohesion’ and ‘citizenship’.[23] It introduced a ‘citizenship test’ under which immigrants seeking Australian citizenship would need to demonstrate a ‘working knowledge of the English language’ and ‘an understanding of basic aspects of Australian society, our culture, and our values and certainly some understanding of our history’.[24] Yet the Howard government’s policy documents also mirrored the Hawke Labor government’s in balancing the celebration of diversity with the affirmation of common values. Moran concludes that multiculturalism survived the Howard government ‘in practice if not in name’.[25]

The Rudd and Gillard Labor governments (2007–2013) reintroduced a commitment to multiculturalist terminology while also maintaining the now-familiar balancing of ‘shared rights and responsibilities’.[26] Continuity along these lines essentially continued under the Abbott–Turnbull–Morrison Coalition governments from 2013.[27]

Prime Minister Morrison lauded ‘our incredibly diverse multicultural society’, ‘an open, tolerant, multicultural Australia’ and ‘the most successful immigration country … in the world’ while also cautioning against a ‘retreat to tribalism’.[28]

An interesting consequence of fluctuations over time in the preferred terminology and in political priorities is the name bestowed on the government department responsible for immigration. Table 1 reports the succession of names since the mass immigration program began in the late 1940s. The recent rhetorical emphasis on citizenship and border protection is readily apparent; for one critic, the changed nomenclature reveals an unwelcome shift in focus, a ‘move from planning the nation’s future to policing its frontier’.[29]

| 1945–1974 | Department of Immigration |

| 1974–1975 | Department of Labor and Immigration |

| 1976–1987 | Department of Immigration and Ethnic Affairs |

| 1987–1993 | Department of Immigration, Local Government and Ethnic Affairs |

| 1993–1996 | Department of Immigration and Ethnic Affairs |

| 1996–2001 | Department of Immigration and Multicultural Affairs |

| 2001–2006 | Department of Immigration and Multicultural and Indigenous Affairs |

| 2006–2007 | Department of Immigration and Multicultural Affairs |

| 2007–2013 | Department of Immigration and Citizenship |

| 2013–2017 | Department of Immigration and Border Protection |

| 2017– | Department of Home Affairs |

Policy actors

Policy development and political debates around immigration and multiculturalism are shaped by a range of policy actors.

Political parties

Policy convergence and bipartisanship, rather than partisan conflict, has mostly characterised the role of the major political parties within this policy domain. There have been instances where this major party bipartisanship has wavered a little or where alleged differences have been exaggerated for tactical advantage in the heat of election campaigns (such as recent arguments about which side is tougher or more effective on ‘border protection’). Nonetheless, in broad terms, the major party bipartisan consensus has generally prevailed, especially on the fundamental structure of the immigration system.

However, bipartisan consensus is tested from time to time. Within the Coalition parties, there can be some sentiment which is sceptical of multiculturalism and instead favours the maintenance of common values. Within the broader membership of the Labor Party, reservations about the ethics of draconian ‘border protection’ policies and empathy for the plight of affected asylum seekers are not infrequently expressed.[30]

Minor parties and independents represented in the federal parliament offer a broader spectrum of perspectives: the Australian Greens have adopted a stance consistently favourable to higher immigration levels and sympathetic to asylum seekers while Pauline Hanson’s One Nation has consistently supported a lower intake and is unwelcoming to asylum seekers.

Public opinion

The range of views among Australian voters is somewhat more polarised. There is some dispute about whether survey data over time show majority support for or against current levels of immigration, with the answer probably dependent on the wording of the questions put to survey respondents.

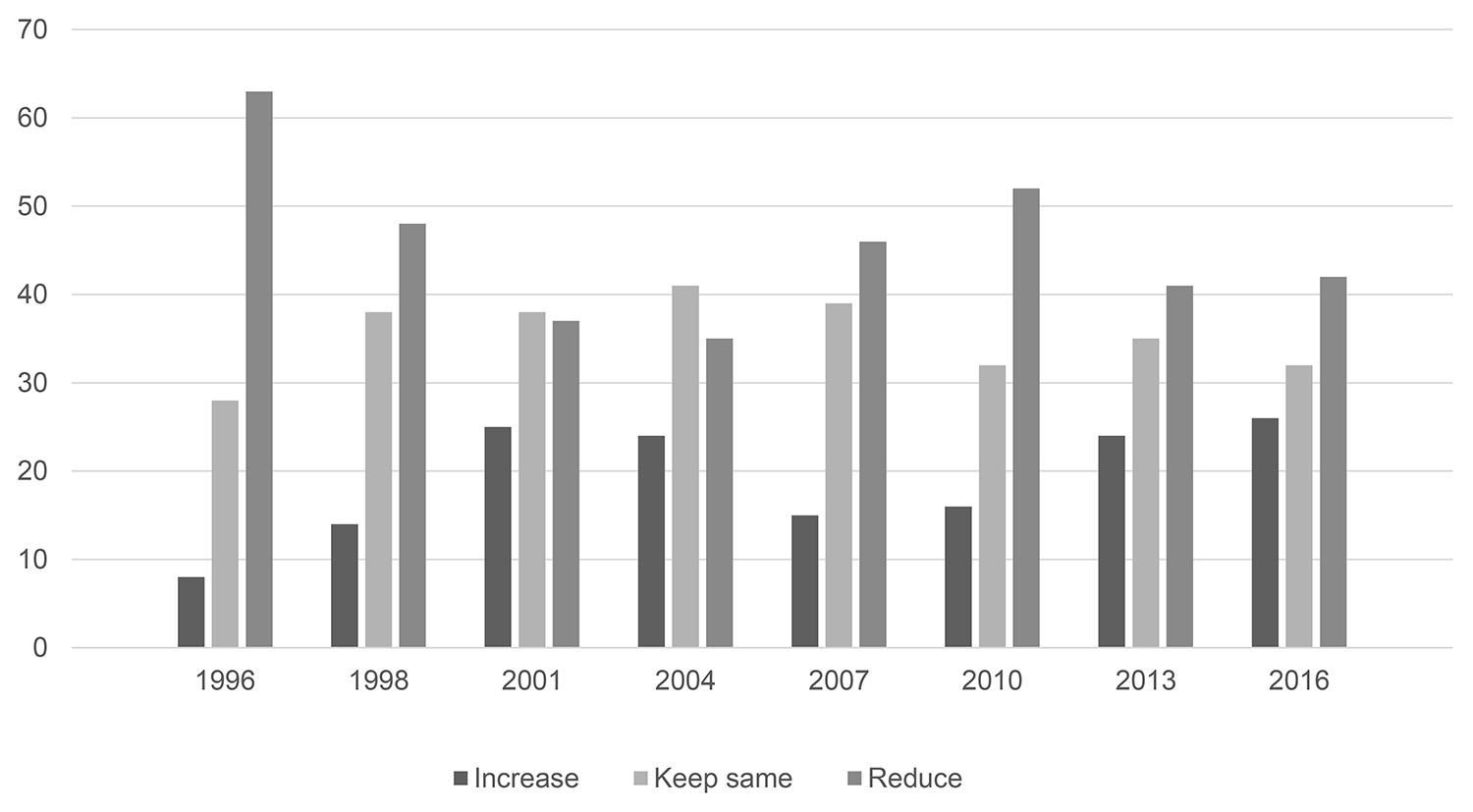

The respected Australian Election Study (AES) national survey is conducted to coincide with each Australian national election. Figure 4 reports the findings for each AES since 1996 on the matter of whether respondents think the immigration levels at the time should be increased, kept the same or decreased. Of the three options, a decreased intake has mostly procured the highest level of support and has consistently been substantially better supported than an increased intake. On the other hand, advocates of a generous immigration intake could combine the ‘increased’ and ‘kept the same’ tallies to claim (with a few exceptions) majority support for at least maintaining the intake.

A Scanlon Foundation study through Monash University noted that, during 2018, ‘a number of polls … reported majority negative sentiment, in the range of 54–72 per cent, favouring a cut in immigration’. The Scanlon Foundation’s own 2018 survey confirmed ‘an increase in the proportion concerned at the level of immigration’ but also indicated that ‘support for a reduction remains a minority viewpoint’ at 45 per cent of respondents.[31]

The same Scanlon Foundation 2018 survey found generally strong support for the proposition that ‘multiculturalism has been good for Australia’. The Scanlon Foundation study also noted ‘the level of negative sentiment towards those of the Muslim faith, and by extension to immigrants from Muslim countries’ as ‘a factor of significance in contemporary Australian society’.[32]

Business

Business interests have generally supported relatively high levels of immigration. It creates a larger supply of potential workers, reduces upward pressure on wages and creates a larger consumer demand for business products.

Betts and Gilding have identified specific business sectors which receive a fairly direct stimulus from immigration as particularly vocal advocates of high intake levels; these sectors include ‘property developers and operators in the housing and construction industries’, ‘the Australian media [which] derive a large part of their advertising revenue from developers and real estate agents’ and ‘other businesses with a domestic market – ranging from gambling to financial services’.[33]

During public debates in 2018 about whether immigration intakes should be reduced, the business sector’s major umbrella organisations – the Business Council of Australia, the Australian Industry Group, the Australian Chamber of Commerce and Industry, and the Property Council of Australia – each declared its opposition to any cuts.[34]

Business organisations also tend to favour a relatively large occupational-skill-based intake in comparison with the family-based intake, because this can advantage them in the recruitment of staff. For particular corporations and business ventures, negotiating favourable arrangements to enable them to access temporary immigrants is also a priority.

Trade unions

The business sector’s favourable stance towards high levels of immigration might be expected to be counterbalanced by scepticism from a trade union movement presumably focused on job protection for the current workforce. Australian trade unions have indeed been vocal critics of high levels of temporary immigration for its association with ‘exploitation and denying job opportunities to local workers’.[35]

However, the trade union movement has generally been supportive of Australia’s permanent immigration program. This was historically important in relation to Australia’s radical shift to mass immigration from the late 1940s.[36] More recently, the ACTU and the union United Voice have joined the Australian Industry Group business lobby in a statement declaring that ‘Australia’s permanent migration program is essential to Australian society and economy’ and that ‘we … do not support any reduction to the scheme’.[37]

Ethnic communities

Australia’s immigration program has fostered the creation of ethnic-minority communities of first-generation members and descendants. These communities naturally have an interest in immigration policy, especially as it applies to rights of admission for other family members, and a particular stake in multicultural policy. They do not necessarily harbour a different range of views on other immigration-related issues; for example, according to Jupp and Pietsch, ‘[s]ome polling suggests that many “ethnic” Australians were just as unsympathetic as the “Anglo” majority to asylum seekers who were perceived to be jumping the gun, especially when that affected family reunion for their own group’.[38]

Seventy years of large-scale immigration have not changed the basic structure of the Australian political system, particularly its domination by the two major party blocs (the Liberal–National Coalition and Labor). However, the political process, and especially the parties, have adjusted to the changed nature of the electorate. Parties now actively court ethnic-minority communities.

Sometimes the policy preferences arising from ethnic-minority communities are articulated through ethnic community organisations, co-ordinated nationally through the Federation of Ethnic Communities Councils of Australia (FECCA). FECCA and its allies were claimed to have had a significant influence over the Hawke Labor government in securing a high proportion of immigration places for family-connection applicants.[39] If that outcome is a test of the influence of the ‘ethnic lobby’, then its influence seems to have since waned.

There is evidence that the same waning impact also applies to patterns of ‘ethnic voting’. The Labor Party had been quite successful during the 1980s and 1990s in disproportionately attracting voting support among members of the Italian Australian, Greek Australian and Maltese Australian communities. Labor’s relative advantage within those communities, however, seems to have declined since then. Australia’s diverse Asia-origin communities likewise seem to have been disproportionately attracted to Labor in the 1990s but again that partisan distinction seems to have since declined.[40]

Nonetheless, an association between ethnic minorities and support for Labor remains visible on the electoral map. An analysis of the 2016 election identifies a raft of electorates in ‘central and eastern Sydney … and in northern, western and south eastern Melbourne … [as] the true Labor heartland and the core of multicultural Australia’.[41] There may be impacts in particular parliamentary seats; the loss by then Prime Minister John Howard of his own seat at the 2007 federal election was attributed in part to the relatively high proportion of Chinese Australians in that electorate.[42]

Advocacy and support groups

The issues around humanitarian immigration, and particularly asylum seekers, have mobilised an articulate, informed and often passionate network of advocacy groups pursuing what they regard as more humane policies. The scale of this sector, ranging from faith-based organisations[43] to social-movement activists,[44] can be gauged from the 200 organisations affiliated with the umbrella Refugee Council of Australia.[45]

Making immigration and multicultural policy

Each year, Cabinet determines an immigration intake target for the coming 12 months and the actual intake normally comes out reasonably close to the announced target. This is an impressive degree of precision in view of its basis in hundreds of thousands of individual applications and in view of some international evidence of other countries finding it difficult to match immigration policy intentions with actual outcomes.[46]

In recent years, there has been a formal opportunity for stakeholder input into the setting of targets.[47] However, the encapsulation of the target/ceiling within the annual budget process, and its implementation thereafter through administrative channels, gives it some insulation from the scrutiny that accompanies processes requiring more specific parliamentary approval. Policy making about Australia’s response to asylum seekers, both potential arrivals and those later held in detention, is somewhat more open in terms of public debate, but is constrained in practice by the general bipartisanship characterising the policy response.

International and intergovernmental interactions

Constitutionally, the arena of Australian immigration policy making is focused at the national level. Section 51(xxvii) of the Australian Constitution gives the Australian national government clear and unambiguous authority over immigration policy. International law provides unambiguous recognition of national sovereignty in relation to the rights of countries to determine their own policies. Nonetheless, in practice, the Australian government needs to take into account both external/international and internal/domestic nuances.

National sovereignty is potentially subject to international influence if a country chooses to enter into international treaties. For example, Australia has long been a signatory to the 1951 Refugee Convention. Australia is also a signatory to the United Nations (UN) Convention on the Law of the Sea which governs interactions in international waters beyond the jurisdiction of Australia’s own maritime boundaries.[48] There have been persistent claims that some of Australia’s policies and practices in relation to the interdiction of asylum-seeker boats and the indefinite offshore detention of asylum seekers violate some of its international obligations under such treaties.[49] The only recourse, even when the complainant is the UN,[50] is essentially via public condemnation and political protest.

Foreign policy and trade considerations provide another international constraint. For example, Australia’s policies and practices on maritime asylum seekers can be a particularly sensitive issue affecting its important relationship with Indonesia, from where most of the boats depart. Australia’s immigration-driven cultural diversification can assist international trade by opening up, through detailed local knowledge and personal contacts, new export markets. International trade agreements to which Australia is a party may in turn carry obligations to grant temporary entry and employment rights to the citizens of trading partners.[51]

An important international detail about Australia’s immigration policy is that there is no restriction on the entry of New Zealand citizens. They are not considered as part of the immigration program if they decide to settle permanently in Australia.

Turning to intra-national considerations, there are considerable consequences for Australia’s state governments which are largely responsible for the provision of infrastructure and services to an expanding population. The strong tendency for immigrants to gravitate to Australia’s metropolitan centres, and especially Sydney and Melbourne, has been an important factor behind recent arguments for the intake to be reduced. Attracting or directing immigrants to regions or states within which population growth would be more welcome would help to remedy this situation. There is a well-established ‘regional’ subcategory within the occupational-skills immigration intake which favours applicants willing to reside in specified regions or states. In late 2018, Prime Minister Scott Morrison proposed inserting a formal role for state governments into the setting of immigration targets based on the willingness of each state to accept additional residents.[52]

Debates and issues

This chapter has already canvassed a number of policy debates around immigration and multiculturalism. Here two other controversies are discussed: the security and environmental sustainability implications of immigration policy settings.

Defence and security

National security had been a foremost consideration as a justification for the policy shift in 1945 towards large-scale immigration. In this context, Australia’s relatively low population and empty spaces were regarded as liabilities for national defence: ‘populate or perish’ was adopted as something of a national slogan.[53]

As the decades passed, Australia’s defence thinking, its relationship with Asian neighbours and the role of military technology had evolved to the point that the 1940s invocation of a direct link between immigration and questions of national security no longer seemed persuasive. By the late 1980s, there had developed ‘something of a consensus, articulated in several reviews of Australian defence policy … that the size of the Australian population has little military relevance’.[54]

Security considerations have re-emerged forcefully as part of recent debates about maritime asylum seekers. A new lexicon of security-laden terminology (border protection, border security, Operation Sovereign Borders) has characterised political discourse in recent years. The deployment of Australian military forces (notably the Navy) in the interdiction of asylum-seeker vessels, along with the formation in 2015 of the Australian Border Force as a kind of paramilitary agency within the Department of Home Affairs, have likewise contributed to the security-centric tone of recent immigration management. To some observers, this has been an overreaction to the actual level of security threat posed by asylum-seeker vessels.[55]

Environmental sustainability

In October 2009, Labor Prime Minister Kevin Rudd effusively declared his support for ‘a big Australia’ arising from the ‘good news that our population is growing’.[56] Less than a year later, his successor as Labor prime minister, Julia Gillard, pointedly abandoned the ‘big Australia’ aspiration, instead declaring support for ‘a sustainable Australia’.[57] This short-cycle policy oscillation illustrates an unresolved policy debate about whether considerations of sustainability, environmental and otherwise, ought to impose a constraint on the scale of immigration.

An increasing population, and/or a rapid rate of population increase, have been argued by some to endanger the natural environment, to impact on resource depletion and energy consumption, and produce increased congestion in the urban environment. This perspective is backed by organisations such as Sustainable Population Australia and by individuals like the entrepreneurial philanthropist Dick Smith.[58]

Nonetheless, the population restraint perspective has secured less traction among mainstream environmental lobby groups. Some years ago, the Australian Conservation Foundation (ACF) endured some internal turmoil over taking a position on the scale of immigration.[59] The ACF’s National Agenda 2018 makes no mention of immigration or population matters.[60]

It has been the claimed impact on the urban rather than the natural environment, in the context of the historically high levels of immigration, which has led in recent years to a stronger voice advocating a reduction in the immigration intake. The Morrison government responded in 2019 by lowering the immigration target.[61]

Until 2019, Australia had not developed, at least not since the ‘populate or perish’ era of the late 1940s, a formal long-term ‘population policy’ addressing the scale, pace and impact of population growth. A number of inquiries and reports had canvassed the issue.[62] In March 2019, the Morrison government moved towards a more formal population policy, with a notable emphasis on infrastructure provision, by releasing a report entitled Planning for Australia’s Future Population.[63]

Conclusions

A startling contrast is evident in how Australia’s immigration and multicultural policies have recently evolved. On the one hand, a generally expansive and cosmopolitan orientation predominates in the immigration and humanitarian programs and in domestic multicultural policies. On the other hand, a tough-minded approach prevails in relation to asylum seekers arriving by sea. Observers discomforted by the asylum seeker policies might be further discomforted to contemplate that the two dimensions may be politically interdependent.

Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull appeared certain of this interdependence. He lectured along these lines in April 2018 to an audience in Germany, a country then facing the consequences of a surge in asylum seeker arrivals. ‘We manage our immigration program very carefully’, Turnbull explained. ‘Migration programs, a multicultural society, need to have a commitment, an understanding and the trust of the people, that the government, their government, is determining who comes to the country’. This means, according to Turnbull, that ‘being in control of your borders is absolutely critical’ and is ‘a fundamental foundation of our success as a multicultural society, as a migration nation as people often describe us’.[64]

The contrasts and possible contradictions embedded within Australia’s immigration and multicultural policies, evolving over time and shaping the country in fundamental ways, add to the fascination and intrigue of this crucial policy domain.

References

Australian Border Force (2014). Video: no way – you will not make Australia home. 15 April. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rT12WH4a92w

Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC) (2018). Fact check: does Australia run the most generous refugee program per capita in the world? Updated 23 February. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2017-12-21/fact-check-george-brandis-refugees-per-capita/9241276

Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) (2018). Migration, Australia, 2016-17. Cat. No. 3412.0. Canberra: ABS. https://bit.ly/326XTi8

—— (2017a). Census of Population and Housing: reflecting Australia – stories from the Census, 2016: Cultural diversity in Australia, 2016. Cat. No. 2071.0. Canberra: ABS. https://bit.ly/2N0vfKX

—— (2017b). Media release: 2016 Census – religion. 27 June. http://www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/abs@.nsf/mediareleasesbyReleaseDate/7E65A144540551D7CA258148000E2B85

Australian Conservation Foundation (ACF) (2018). Ten actions to protect nature and stop climate change: ACF’s National Agenda 2018. Carlton, Vic.: ACF. https://bit.ly/2prdr2N

Australian Government (2019). Planning for Australia’s future population. Canberra: Australian Government. https://www.pmc.gov.au/sites/default/files/publications/planning-for-australias-future-population.pdf

—— (2017). Multicultural Australia: united, strong, successful. Canberra: Australian Government. https://www.homeaffairs.gov.au/mca/Statements/english-multicultural-statement.pdf

—— (2011). The people of Australia: Australia’s multicultural policy. Canberra: Australian Government. http://apo.org.au/system/files/27232/apo-nid27232-75716.pdf

Australian Human Rights Commission (AHRC) (2017). Asylum seekers, refugees and human rights: snapshot report, 2nd edn. Sydney: AHRC. https://www.humanrights.gov.au/sites/default/files/document/publication/AHRC_Snapshot%20report_2nd%20edition_2017_WEB.pdf

Betts, Katherine (1999). The great divide: immigration politics in Australia. Sydney: Duffy & Snellgrove.

—— (1991). Australia’s distorted immigration policy. In David Goodman, D.J. O’Hearn and Chris Wallace-Crabbe, eds. Multicultural Australia: the challenge of change, 149–77. Newham, Vic.: Scribe.

Betts, Katherine and Michael Gilding (2006). The growth lobby and Australia’s immigration policy. People and Place 14(4): 40–52.

Birrell, Robert, and Katherine Betts (1988). The FitzGerald Report on immigration policy: origins and implications. Australian Quarterly 60(3): 271–4. DOI: 10.2307/20635486

Boucher, Anna (2013). Bureaucratic control and policy change: a comparative venue shopping approach to skilled immigration policies in Australia and Canada. Journal of Comparative Policy Studies 16(4): 349–67. DOI: 10.1080/13876988.2012.749099

Bramston, Troy (2018). Labor left poised for showdown on reforms. The Australian, 10 December.

Burstein, Myer, Leonie Hardcastle and Andrew Parkin (1994). Immigration management control and its policy implications. In Howard Adelman, Allan Borowski, Myer Burstein and Lois Foster, eds. Immigration and refugee policy: Australia and Canada compared, 187–226. Carlton, Vic.: Melbourne University Press.

Button, John (2018). Dutton’s dark victory. The Monthly, February.

Calwell, Arthur (1945). Migration: Commonwealth government policy. Speech to House of Representatives, 2 August. http://historichansard.net/hofreps/1945/19450802_reps_17_184/#subdebate-11-0

Cameron, S., and I. McAllister (2016). Trends in Australian political opinion: results from the Australian Election Study 1987-2016. Canberra: Australian National University School of Politics and International Relations. https://bit.ly/2JADVpq

Department of Home Affairs (DHA) (2019). Discussion paper: Australia’s humanitarian program 2019–20. Canberra: DHA. https://www.homeaffairs.gov.au/reports-and-pubs/files/2019-20-discussion-paper.pdf

—— (2018a). 2017–18 migration program report. Canberra: DHA. https://www.homeaffairs.gov.au/research-and-stats/files/report-migration-program-2017-18.pdf

—— (2018b). Australia’s offshore humanitarian program: 2017–18. Canberra: DHA. https://www.homeaffairs.gov.au/research-and-stats/files/australia-offshore-humanitarian-program-2017-18.pdf

—— (2018c). Working Holiday Maker visas granted pivot table: 2018–19 to 30 September 2018 – comparisons with previous years. https://data.gov.au/dataset/visa-working-holiday-maker/resource/c1b2d652-5bcb-4120-8bef-04d0b7912190

—— (2018d). Temporary resident (skilled) visas granted pivot table: 2018–19 to 30 September 2018 – comparisons with previous years. https://data.gov.au/dataset/visa-temporary-work-skilled/resource/d7c01bfa-2072-420a-a38b-2ba99351742a

—— (2018e). Student visa and Temporary Graduate visa program report. Canberra: DHA. https://www.homeaffairs.gov.au/research-and-stats/files/student-temporary-grad-program-report-jun-2018.pdf

—— (2017). Managing Australia’s migrant intake. Canberra: DHA. https://www.homeaffairs.gov.au/reports-and-pubs/files/managing-australias-migrant-intake.pdf

Department of Immigration and Border Protection (DIBP) (2017). 2016–17 migration programme report. Canberra: DIBP. https://www.homeaffairs.gov.au/research-and-stats/files/report-on-migration-program-2016-17.pdf

—— (2013a). Video: you won’t be settled. 29 August. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bvz3U-JOvOU

—— (2013b). What’s in a name. https://web.archive.org/web/20140123005605/https://www.immi.gov.au/about/anniversary/whats-in-a-name.htm

Department of Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities (DSEWPC) (2011). A sustainable population strategy for Australia. Canberra: DSEWPC. https://bit.ly/2pdBHFl

Elton-Pym, James (2018). States in best position to determine migrant numbers: Morrison. SBS News, 12 November. https://bit.ly/344H2xt

Gordon, Josh (2010). Gillard rejects Big Australia. Sydney Morning Herald, 27 June.

Hardcastle, Leonie (2010). Big picture, small picture: perspectives on Asia among Anglo-Celtic working-class Australians. Saarbrücken, DE: Lambert Academic Publishing.

Higgins, Claire (2017). Asylum by boat: origins of Australia’s refugee policy. Sydney: UNSW Press.

Howard, John (2006). Joint press conference with Mr Andrew Robb, parliamentary secretary to the minister for immigration and multicultural affairs. Sydney, 11 December. https://bit.ly/3Hxj4AT

Howe, Joanna, Andrew Stewart and Rosemary Owens (2018). Temporary migrant labour and unpaid work in Australia. Sydney Law Review 40(2): 183–211.

Jupp, James (2009). Immigration and ethnicity. Australian Cultural History 27(2): 157–65. DOI: 10.1080/07288430903165303

Jupp, James, and Juliet Pietsch (2018). Migrant and ethnic politics in the 2016 election. In Anika Gauja, Peter Chen, Jennifer Curtin and Juliet Pietsch, eds. Double disillusion: the 2016 Australian federal election, 661–79. Canberra: ANU Press.

Kell, Peter (2014). Global shifts in migration policy and their implications for skills formation, nations, communities and corporations. In Tom Short and Roger Harris, eds. Workforce development: strategies and practices, 17–31. Singapore: Springer Science.

Klein, Natalie (2014). Assessing Australia’s push back the boats policy under international law. Melbourne Journal of International Law 15(2): 414–43.

Lewis, Rosie (2019). Last four remaining refugee children on Nauru leave for US. The Australian, 27 February. https://bit.ly/2Oc2s5R

Mares, Peter (2016). Not quite Australian: how temporary migration is changing the nation. Melbourne: Text Publishing.

Markus, Andrew (2018). Mapping social cohesion: the Scanlon Foundation surveys 2018. Melbourne: Scanlon Foundation. https://scanlonfoundation.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/Social-Cohesion-2018-report-26-Nov.pdf

McAllister, Ian (2011). The Australian voter: 50 years of change. Sydney: UNSW Press.

McCauley, Dana, and Michael Koziol (2018). Australia needs ‘well managed population growth’, not cuts: business lobby. Sydney Morning Herald, 21 November.

McManus, Sally (2018). Press Club speech: change the rules. Canberra, 21 March. https://www.actu.org.au/media/1033746/180320-national-press-club-speech-sally-mcmanus-march-21-2018.pdf

Migrant Workers’ Taskforce (2019). Report. Canberra: Australian Government. https://bit.ly/3vV75ug

Migration Council of Australia (2018). National Compact on Permanent Migration. https://bit.ly/3vOwjdQ

Moran, Anthony (2017). The public life of Australian multiculturalism. Cham, CH: Palgrave Macmillan.

Morrison Government (2019). Media release: a plan for Australia’s future population. https://www.pm.gov.au/media/plan-australias-future-population

Morrison, Scott (2019). Speech to Australia–Israel Chamber of Commerce. Melbourne, 18 March. https://www.pm.gov.au/media/australia-israel-chamber-commerce-speech

—— (2018). Press conference with the attorney-general. 13 December. https://www.pm.gov.au/media/press-conference-attorney-general-0

Office of Multicultural Affairs (OMA) (1989). National agenda for a multicultural Australia. Canberra: Australian Government Publishing Service.

Pakulski, Jan (2014). Confusions about multiculturalism. Journal of Sociology 50(1) 23–36. DOI: 10.1177/1440783314522190

Parkin, Andrew, and Leonie Hardcastle (1990). Immigration policy. In Christine Jennett and Randal Stewart, eds. Hawke and Australian public policy, 315–38. South Melbourne: Macmillan.

Phillips, J. (2016). Australia’s working holiday maker program: a quick guide. Parliamentary Library Research Paper (2016–17). Canberra: Parliament of Australia. https://parlinfo.aph.gov.au/parlInfo/download/library/prspub/4645762/upload_binary/4645762.pdf

Phillips, J., and J. Simon-Davies (2017). Migration to Australia: a quick guide to the statistics. Parliamentary Library Research Paper (2016–17). Canberra: Parliament of Australia. https://parlinfo.aph.gov.au/parlInfo/download/library/prspub/3165114/upload_binary/3165114.pdf

Productivity Commission (2016). Migrant intake into Australia. Report No. 77. Canberra: Productivity Commission.

Refugee Council of Australia (2018a). Operation Sovereign Borders and offshore processing statistics. https://bit.ly/47QkeST

—— (2018b). About us. https://www.refugeecouncil.org.au/about-us/

—— (2014). Myth: asylum seekers who arrive by boat are a security threat. https://www.refugeecouncil.org.au/getfacts/mythbusters/security-threat/

Rudd, Kevin (2013). Transcript of joint press conference – Brisbane. https://bit.ly/48S9IMk

—— (2009). Transcript of interview with Kerry O’Brien, 7:30 Report, 22 October. https://pmtranscripts.pmc.gov.au/taxonomy/term/13?page=55

Shanahan, Dennis (2018). Turnbull tells Merkel to control her borders. The Australian, 25 April. https://bit.ly/2Jjicly

Sherrell, Henry (2017). An odd couple? International trade and immigration policy. Flagpost, 26 October. https://bit.ly/2Jl3dYG

Smith, Dick (2011). Dick Smith’s population crisis: the dangers of unsustainable growth for Australia. Crows Nest, NSW: Allen & Unwin.

Tavan, Glenda (2004). The dismantling of the White Australia policy: elite conspiracy or will of the Australian people? Australian Journal of Political Science 39(1): 109–25. DOI: 10.1080/1036114042000205678

Tazreiter, Claudia (2010). Local to global activism: the movement to protect the rights of refugees and asylum seekers. Social Movement Studies 9(2): 201–14. DOI: 10.1080/14742831003603349

Treasury (2015). 2015 intergenerational report: Australia in 2055. Canberra: Treasury. https://static.treasury.gov.au/uploads/sites/1/2017/06/2015_IGR.pdf

Turnbull, Malcolm (2017). Press conference with the minister for immigration and border protection. 18 April. https://bit.ly/4b8INxa

United Nations (2017). UN urges Australia to find humane solutions for refugees, asylum seekers on Manus Island. UN News, 22 December. https://news.un.org/en/story/2017/12/640351-un-urges-australia-find-humane-solutions-refugees-asylum-seekers-manus-island

Vamplew, W. ed. (1987). Australians: historical statistics. Broadway, NSW: Fairfax, Syme & Weldon.

Warhurst, John (1993). The growth lobby and its opponents: business, unions, environmentalists and other interest groups. In James Jupp and Marie Kabala, eds. The politics of Australian immigration, 181–203. Canberra: Bureau of Immigration Research/Australian Government Publishing Service.

Wilson, Erin (2011). Much to be proud of, much to be done: faith-based organisations and the politics of asylum in Australia. Journal of Refugee Studies 24(3): 548–64. DOI: 10.1093/jrs/fer037

About the authors

Andrew Parkin is a professor in Flinders University’s College of Business, Government and Law. Previously, he was the University’s Deputy Vice-Chancellor (Academic). A national fellow of the Institute of Public Administration Australia, he has served as editor of the Australian Journal of Political Science, president of the Australasian Political Studies Association and a member of the Australian Research Council’s College of Experts. His academic publications span many aspects of politics and public policy, including immigration, housing, urban government, the Labor Party, federalism and South Australian politics. He was co-editor of nine editions of Government, politics, power and policy in Australia.

Leonie Hardcastle is a research associate within the Flinders University Library and an associate of the Flinders Institute for Research in the Humanities. She has a number of academic publications analysing immigration and ethnic affairs policy as well as a book, Big picture, small picture: perspectives on Asia among Anglo-Celtic working-class Australians (2010). Dr Hardcastle has taught at the university level in international relations and Asian studies as well as public policy and management. She has worked as an assessor and chief moderator for the national Public Sector Management Program.

- Parkin, Andrew, and Leonie Hardcastle (2024). Immigration and multiculturalism. In Nicholas Barry, Alan Fenna, Zareh Ghazarian, Yvonne Haigh and Diana Perche, eds. Australian politics and policy: 2024. Sydney: Sydney University Press. DOI: 10.30722/sup.9781743329542. ↵

- Hardcastle 2010, chapter 5. ↵

- Betts 1999. ↵

- Tavan 2004. ↵

- ABS 2017a. ↵

- ABS 2017b. ↵

- ABC 2018. ↵

- Higgins 2017. ↵

- Refugee Council of Australia 2018a. ↵

- Rudd 2013. ↵

- DIBP 2013a. ↵

- Australian Border Force 2014. ↵

- Lewis 2019. ↵

- Productivity Commission 2016, 30. ↵

- Productivity Commission 2016, 191. ↵

- Howe, Stewart and Owens 2018. ↵

- Migrant Workers’ Taskforce 2019, 5. ↵

- Mares 2016. ↵

- Kell 2014. ↵

- Turnbull 2017. ↵

- Pakulski 2014, 23. ↵

- OMA 1989, vii. ↵

- Moran 2017, chapter 4. ↵

- Howard 2006. ↵

- Moran 2017, 109. ↵

- Australian Government 2011, 7. ↵

- Australian Government 2017. ↵

- Morrison 2019; Morrison 2018. ↵

- Button 2018. ↵

- Bramston 2018. ↵

- Markus 2018, 2. ↵

- Markus 2018, 3. ↵

- Betts and Gilding 2006, 43–4. ↵

- McCauley and Koziol 2018. ↵

- McManus 2018. ↵

- Warhurst 1993. ↵

- Migration Council of Australia 2018. ↵

- Jupp and Pietsch 2018, 665. ↵

- Betts 1991; Birrell and Betts 1988. ↵

- McAllister 2011, 134–6. ↵

- Jupp and Pietsch 2018, 671. ↵

- Jupp 2009. ↵

- Wilson 2011. ↵

- Tazreiter 2010. ↵

- Refugee Council of Australia 2018b. ↵

- Boucher 2013; Burstein, Hardcastle and Parkin 1994. ↵

- DHA 2019; DHA 2017. ↵

- Klein 2014. ↵

- AHRC 2017. ↵

- United Nations 2017. ↵

- Sherrell 2017. ↵

- Elton-Pym 2018. ↵

- For the seminal speech by the then minister for immigration, see Calwell 1945. ↵

- Parkin and Hardcastle 1990, 332. ↵

- Refugee Council of Australia 2014. ↵

- Rudd 2009. ↵

- Gordon 2010. ↵

- Smith 2011. ↵

- Warhurst 1993, 199–202. ↵

- ACF 2018. ↵

- Morrison Government 2019. ↵

- DSEWPC 2011; Treasury 2015. ↵

- Australian Government 2019. ↵

- Shanahan 2018. ↵