10 Courts

Grant Hooper

Key terms/names

appeal, appellate jurisdiction, common law, court hierarchy, jurisdiction, original jurisdiction, rule of law, separation of powers, statutory law

The courts (also referred to as the judiciary) are a central and critical part of Australia’s constitutional system.[1] They are one of the three arms of government, the other two being the legislature (also referred to as parliament) and the executive. Due to their lack of independent resources and enforcement mechanisms, the courts are often called the least powerful arm of government.[2] Yet this description belies their actual importance.

The specific and essential role played by the courts is providing binding and authoritative decisions when controversies arise between citizens or governments, or between the government and its citizens, regardless of whether the rights in issue relate to life, liberty or property.[3]

Australian courts are modelled on their English counterparts, and before Federation each colony had a separate court system that was ultimately answerable on questions of law to the Privy Council in the UK. After Australia’s Federation in 1901 the separate state systems continued, but the court hierarchy was modified by inserting the High Court of Australia between the state courts and the Privy Council. Recourse to the Privy Council was finally removed in 1986, leaving the High Court as the apex court and, as such, the ultimate arbitrator of the law in Australia.[4]

Upon its creation the High Court was also given its own original jurisdiction by the Australian Constitution (the Constitution). Although not expressly provided for in the Constitution, this jurisdiction (borrowing from the USA) was assumed to include the ability to invalidate legislation that is not supported by, or is contrary to, the Constitution. As a matter of convenience, the Constitution also allowed state courts and other courts that may be created by the Commonwealth parliament to be given the ability to exercise federal/Commonwealth judicial power. This has led to an integrated, albeit complex, court system.[5]

What decisions do courts make?

Although eluding precise definition,[6] the classic starting point for determining what a court does (i.e. what judicial power is) is the following statement of Griffith CJ in Huddart, Parker and Co. Pty Ltd v Moorehead:

I am of the opinion that the words ‘judicial power’ as used in sec. 71 of the Constitution mean the power which every sovereign authority must of necessity have to decide controversies between its subjects, or between itself and its subjects, whether the rights relate to life, liberty or property. The exercise of this power does not begin until some tribunal which has power to give a binding and authoritative decision (whether subject to appeal or not) is called upon to take action.[7] [emphasis added]

This statement can be said to have three key components: controversies, rights and a binding and authoritative decision.

The controversies that the courts typically decide can be divided into two legal categories: private law and public law. Private law incorporates disputes between ‘subjects’ or citizens and includes, for example, tort, contract and defamation law. Public law on the other hand generally involves disputes between government and its citizens or disputes between governments (e.g. state versus state or state versus Commonwealth). It typically encompasses constitutional, administrative and criminal law. However, due to its importance, criminal law is often treated as its own separate category.

The ‘rights’ that courts adjudicate upon are existing ‘legal rights’ rather than future rights (the creation of future rights is generally seen as a legislative power). Such rights are found in the common law or granted by the legislature through statutes.

Perhaps the most essential power of the courts is to provide a binding and authoritative decision so that the dispute between the parties is finally determined, at least once any appeal process is completed. Once authoritatively determined, the decision, whether private or public in nature, can be enforced by the executive government if it is not willingly accepted by one of the parties.

Although not specifically mentioned in the statement of Griffith CJ quoted above, other cases emphasise the importance of a fourth feature of the courts’ decision-making process: to adjudicate a controversy by applying ‘judicial process’.[8] ‘Judicial process’ will be touched upon when discussing the separation of powers doctrine later in this chapter. It is sufficient for now to observe that ‘judicial process’ is deciding a controversy ‘in accordance with the methods and with a strict adherence to the standards which characterise judicial activities’.[9]

Historical development

Australia’s common law system is inherited from England. The term common law reflects one of this legal system’s theoretical aims: to create a ‘common’ system of law. That is, a system of law that applies to all, regardless of wealth, station or political influence. From a practical perspective, common law rules are created by the courts when they decide a dispute. To explain how it has decided a particular dispute, the court issues a judgement outlining the rules of law that have been applied. The rules of law or precedents in these judgements are then developed, modified or extended by later courts when they decide similar or analogous disputes. Courts that are lower in the hierarchy must follow the precedents created by higher courts. The requirement that judges follow the judgements of earlier courts is referred to as the doctrine of precedent.

In England, the common law has existed since the 12th century, when the King appointed judges to act as his ‘surrogates’ to dispense justice. The judges were known collectively as the King’s Court.[10]While originating in a time when the King of England ruled with almost absolute power, the common law was not developed to only and always benefit the King. Rather, the common law ‘was founded in notions of justice and fairness of the judges, consolidated by their shared culture, their professional collegiality, and a growing tradition’.[11] Indeed, with the rise of the common law there also gradually developed a view that the King’s power was not absolute but was subject to limits. Of course, the King’s power diminished further over time, while the power of a new institution – parliament – grew. Parliament’s growth, in turn, saw its rules of law (i.e. legislation) replace the common law as the most ‘significant source of new rules’.[12] Yet parliament’s rise arguably changed the initial focus of the courts rather than diminished their significance. Their role is still to decide controversies brought before them by citizens or governments; but they will now often start with a legislative rule rather than a common law one, examining precedents to determine how the legislative rule has been and should be interpreted and how it has been applied by previous courts.

The establishment of courts in Australia

Before the First Fleet left for Australia in 1787, legislation and letters patent allowed for the creation of a criminal court and civil court respectively in New South Wales (NSW). These courts were established upon the First Fleet’s arrival but were initially staffed by military officers. Later, when the first judge was appointed, he was required to follow any order given by the governor who, for all intents and purposes, exercised both legislative and executive power. It was not until the passing of the New South Wales Act 1823 (UK) that the colonial judges obtained the same level of independence and security of tenure held by their English counterparts.[13]

The New South Wales Act 1823 also established separate Supreme Courts in NSW and Tasmania and provided for the establishment of inferior courts – that is, courts below the Supreme Courts. Ultimately, a similar court system was established in each Australian colony and continues, with some modifications, today (today the inferior courts are generally called District, Local or Magistrate’s courts).

On 1 January 1901 the Constitution came into effect and the Commonwealth of Australia was born. As Blackshield and Williams observe:

The system of federalism created by the Australian Constitution involves two tiers of government in which power is divided between the Commonwealth and the States. Each tier has its own institutions of government, with its own executive, parliament and judicial system.[14]

Consequently, the colonial (now state) court systems continued, but there would now also be federal courts and, in particular, the High Court of Australia, created under section 71 of the Constitution. Under sections 75 and 76 of the Constitution, the High Court could hear and decide certain matters involving Commonwealth power – that is, it would hear the matters in its original jurisdiction. Under section 73, the High Court would also hear appeals from the state Supreme Courts and any federal courts that would be created.

It was clear that the High Court of Australia was generally to operate in the same manner as the English common law courts. However, there was one significant difference. Because England did not have a written constitution, the English courts accepted that they did not have a constitutional role, in the sense that they did not rule on the constitutional validity of legislation. In contrast, borrowing from the USA, which did have a written constitution, it was assumed that the Australian High Court would declare Australian legislation (whether state or Commonwealth) invalid if it exceeded the constitutional power of the enacting parliament or infringed an express or implied limit in the Constitution.[15]

The Constitution also provided in section 71 that the Commonwealth parliament could create other federal courts. Although a Federal Court of Bankruptcy was created in 1930 and an Industrial Court in 1957, it was not until the 1970s that a generalised system of federal courts was established. This began with the creation of the Family Court of Australia in 1975 and the Federal Court of Australia in 1976. As a result of the increasing workload in both the Family and Federal Courts, in 1999 the Federal Magistrates Court, now called the Federal Circuit Court, was established.

Court hierarchy

The Australian court system has many different courts with different responsibilities. Each court is regulated by an Act of parliament. The federal courts, including the High Court, are regulated by an Act of the Commonwealth parliament. The state courts are regulated by their respective state parliaments. The Australian Capital Territory and Northern Territory courts are also regulated by their respective parliaments, although they owe their ultimate existence to Commonwealth legislation.[16]

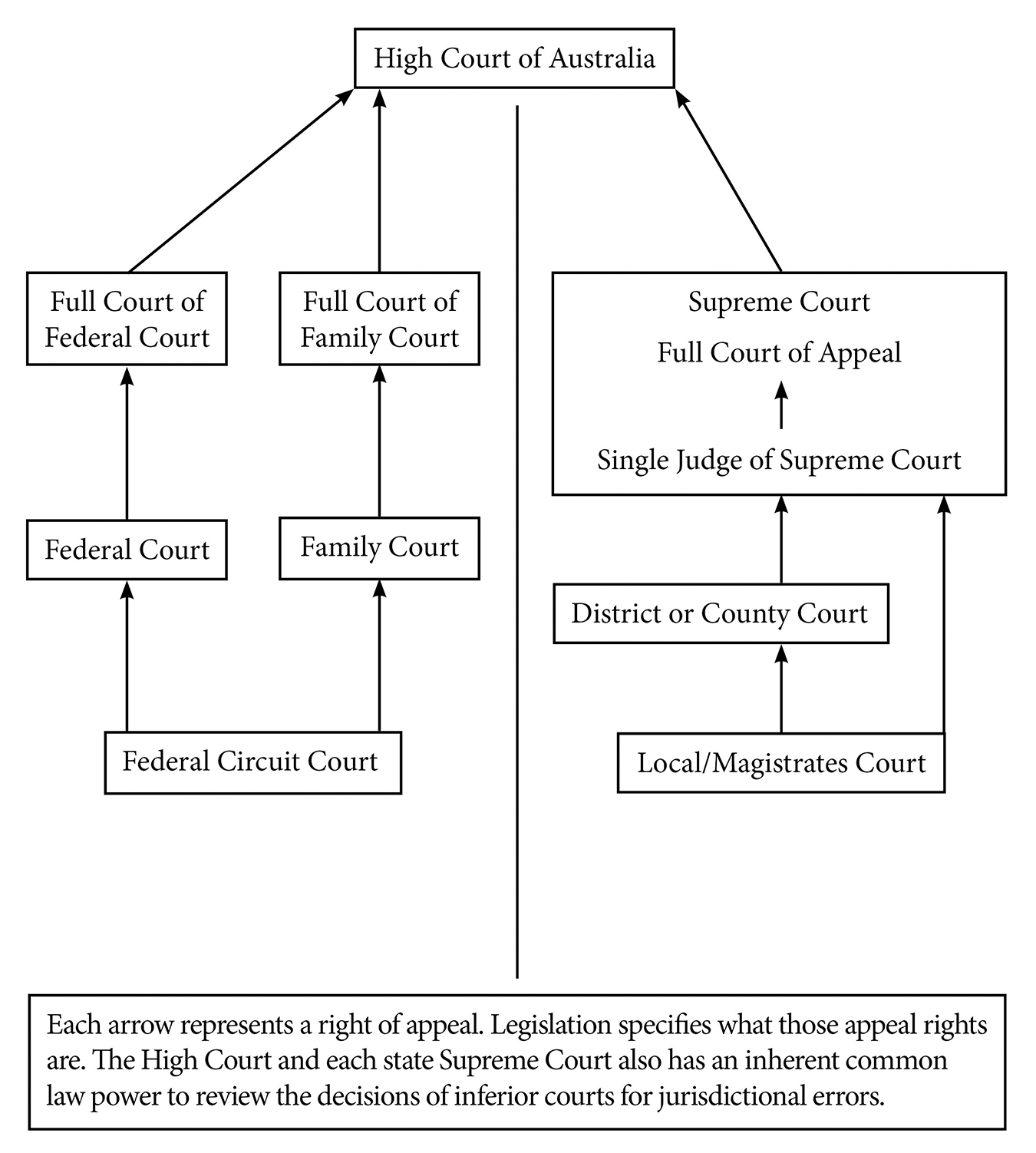

Despite the number and different types of courts, there is a reasonably clear hierarchy, with the High Court at the apex of what can be described as a unified system.[17] It is a hierarchy in the sense that courts are ranked from highest to lowest. Figure 1 provides a general overview of this hierarchy. The hierarchy in turn facilitates the operation of three important characteristics of the modern common law system:

- the balancing of specialist knowledge with more general legal knowledge

- an appeal or judicial review process

- the doctrine of precedent.[18]

While providing a general overview, Figure 1 is somewhat of a simplification for two reasons. First, the division between federal and state courts may give the impression that state courts only exercise their respective state’s judicial power; however, they also exercise federal power. Second, while the court system in each state and territory follows the general structure shown in the figure, in reality each system is more complex; other, more specialised courts have been created and there may be slight differences in the appeal processes.

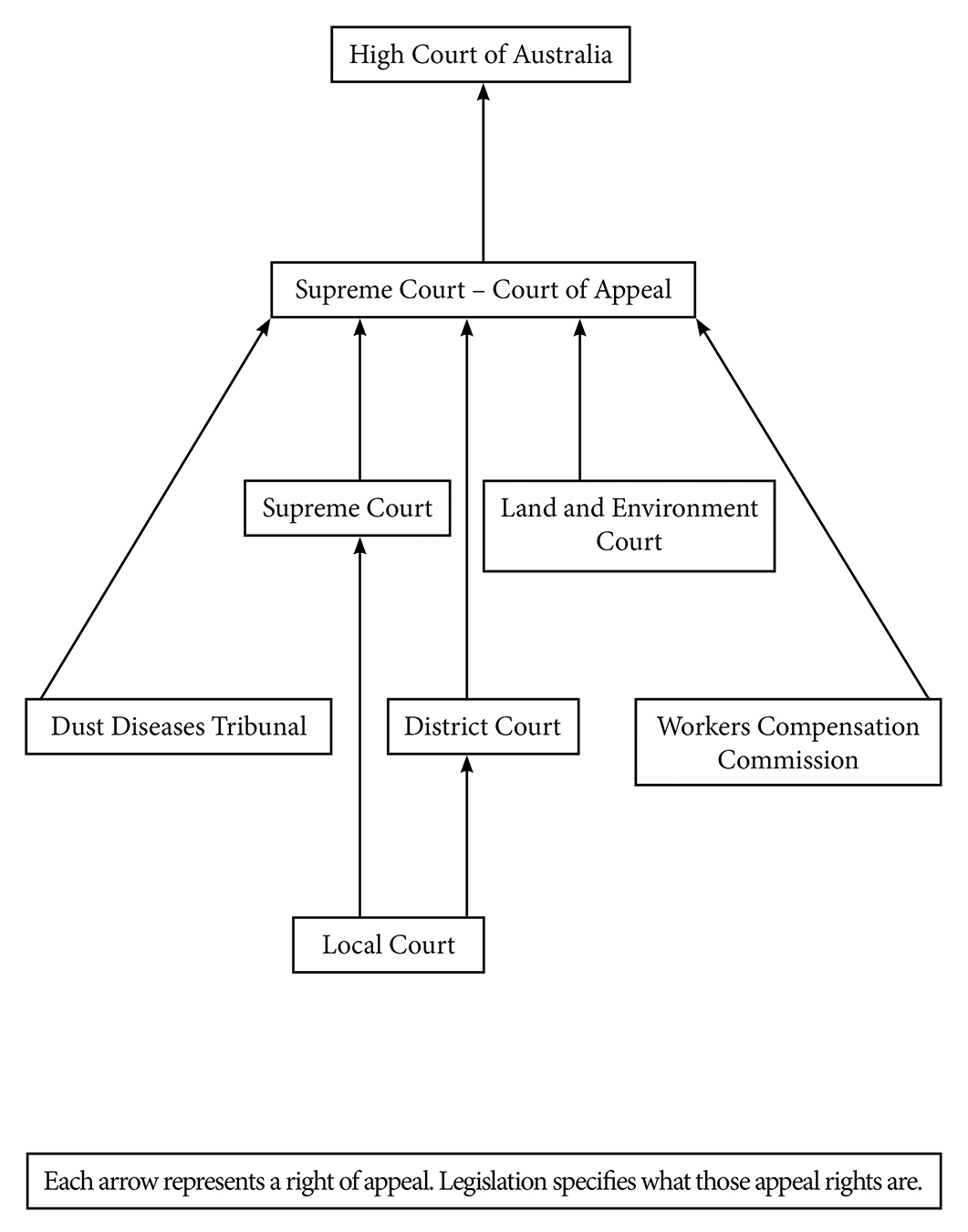

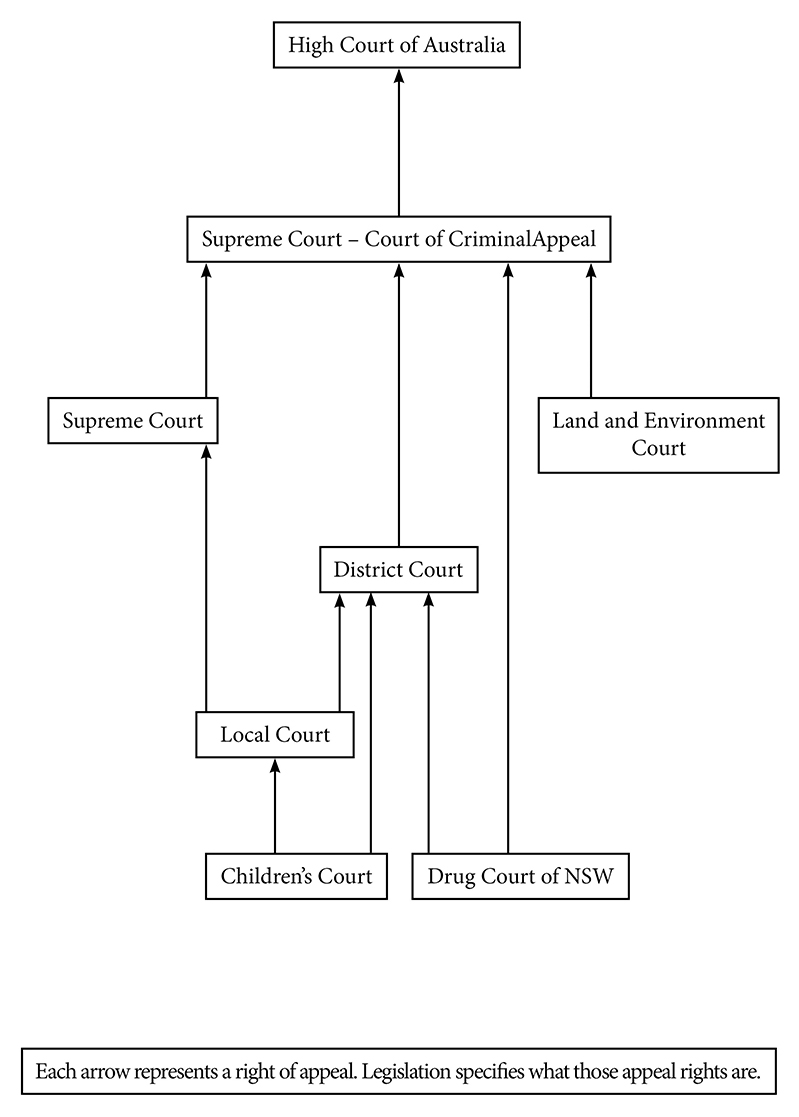

In each state and territory, it is generally accepted that courts lower in the hierarchy should deal with less important matters (both in monetary value and seriousness) and that for some types of cases there should be an initial hearing before a judge with expertise in the particular subject matter before them. In NSW, for example, the Local Court can hear civil cases with a value of up to $100,000, the District Court up to $750,000 and the Supreme Court any amount. Similarly, there are other courts in the state that deal with particular types of matters, and there are specialist divisions within the Local and Supreme Courts that deal with either civil or criminal matters. Figure 2 provides an overview of the NSW civil court structure and Figure 3 provides an overview of the criminal court structure.

Greater integration: the exercise of federal judicial power by state courts

While the USA constitution provided much of the inspiration for the drafting of Chapter III of the Constitution, which deals with the federal court system, there are two very significant differences that have meant Australia’s court structure is far more integrated.

The first difference is that in the USA the federal and state court systems are quite distinct. As the three figures show, in Australia the High Court hears appeals from federal, state and territory courts. This means that the High Court has been able to establish ‘one Australian common law’[19] rather than overseeing a different common law in each state and territory and at the federal level.

The second difference is that provision was made in sections 71 and 77(iii) of the Constitution for the Commonwealth parliament not only to create federal courts but to also allow state courts to exercise federal judicial power.[20]

Giving state courts the power to exercise federal jurisdiction generally, rather than in limited circumstances, was a uniquely Australian development and is known as the autochthonous expedient.[21] Autochthonous means indigenous or native to the soil and the term expedient acknowledges that it was seen as a practical measure to both simplify the resolution of disputes that may be brought before a court under the Constitution, common law or state legislation[22] and delay the need and cost of setting set up a new federal court structure beneath the High Court.[23] Even now that a quite extensive federal court system has been created, the state courts continue to hear most criminal cases brought under federal law.[24]

Although not expressly provided for in the Constitution, Australia’s court system has become even more integrated through cross-vesting legislation passed by the Commonwealth and by each state and territory, allowing the Supreme Courts (and to a lesser extent the Federal and Family Courts) to exercise each other’s jurisdiction. The Jurisdiction of Courts (Cross Vesting) Act 1987 (Cth) provides, for example, that in civil matters the Supreme Courts can exercise federal, as well as other states’, jurisdiction. It then provides for the transfer of proceedings to the most appropriate court. However, while federal jurisdiction can be vested in state courts, the Constitution does not allow state jurisdiction to be vested in federal courts.[25]

Key constitutional principles

There are a number of fundamental doctrines found in the Constitution. They include ‘the rule of law, judicial review, parliamentary sovereignty, the separation of powers, representative democracy, responsible government and federalism’.[26] While each principle influences how courts operate in Australia, two principles in particular can be said to be part of the courts’ DNA. These are the rule of law and the separation of judicial power.

The rule of law

It is commonly accepted that the rule of law is an essential feature or sign of a healthy democratic society. Yet, despite its importance, what the rule of law actually means is highly contested. This is because it can be said to be a political rather than legal concept or an aspirational rather than legal right. Nevertheless, most conceptions of the rule of law start with the ideal that there should be known laws that are administered fairly and that everyone is subject to,[27] whether they are poor, rich, weak, powerful, a private citizen, a public servant or a member of parliament.

While the rule of law is a cultural commitment shared between all three arms of government, the courts are, and see themselves as, central to its enforcement in Australia. The courts enforce the law not only by interpreting it and issuing authoritative and binding judgements but also by applying a process in which the parties in dispute can be seen to have received a fair hearing. This process culminates in written reasons. Written reasons are not only necessary for the doctrine of precedent to operate effectively, they also ensure that the parties and others who may be affected by the law know why the decision was reached. This, in turn, supports the presumption that the law is being administered in an open, public and ultimately fair manner. Importantly, and entwined with the doctrine of the separation of judicial power, this judicial process is designed to ensure that the law is administered as it exists and not as the executive government desires or believes it should be. In this regard, the High Court has emphasised that ‘all power of government is limited by law’ and that it is role of the judiciary to enforce the law and the limits it imposes.[28]

The separation of judicial power

A separation of powers exists when the power of government is divided between the legislature, the executive and the courts. Generally speaking:

the legislature enacts laws; the executive applies those laws in individual cases; and in the event that a dispute arises about the meaning or application of a law, the dispute is resolved conclusively by the judiciary.[29]

A strict separation of powers is enshrined in the USA constitution, but it has never existed in England. However, in England parliament has recognised the importance of an independent judiciary since at least 1701.[30] Australia has adopted somewhat of a middle ground between the USA and English approaches. It only applies a strict separation of power to federal courts (including the High Court) but still provides the state Supreme Courts with a significant level of independence.

Federal courts owe their existence to the Constitution, which creates a strict separation of power between the courts and the other two arms of government. This separation of powers is commonly known as the Boilermaker’s principle and means that only courts created under, or given power through, Chapter III of the Constitution can exercise Commonwealth judicial power and that the same courts are not to be given or to exercise Commonwealth executive or legislative powers, with some established exceptions.[31] Consequently, not only is the independence of a federal court guaranteed, their independence and integrity cannot be undermined by giving them, for example, a political and potentially damaging function.

State courts, which were created like their English counterparts, are not protected by a strict separation of judicial power.[32] This means that state parliaments can vest state judicial power in other institutions or require courts to undertake non-judicial roles. However, as state courts are now part of an integrated court system under the Constitution and can be vested with federal judicial power, the High Court has held that there is a limit to what state parliaments can require them to do as they must continue to bear the essential or defining characteristics of a court. This is known as the Kable principle.[33]

The defining characteristics that have been said to be attributable to all courts, whether federal or state, include not only the ‘reality and appearance of the court’s independence and impartiality’[34] but also important aspects of the judicial process traditionally applied by the courts in reaching a decision, such as:

- ‘the application of procedural fairness’

- ‘adherence, as a general rule, to the open court principle’

- ‘the provision of reasons for decisions’.[35]

Political impact of the High Court

As one of the three arms of government, the role of the courts is inherently political. This is particularly true of the High Court, which is Australia’s apex court and the final interpreter of the Constitution. The High Court’s judgements can have, and have had, a significant and lasting impact on the shape of Australia’s ‘political system and process’.[36] Further, as Turner has observed, the High Court ‘is an important political forum used to advance or stymie political programs’, its decisions ‘have significant political and societal implications’ and cases may be brought before it to try and influence government policy.[37]

Despite the central role it has played and continues to play in Australian politics, the High Court inevitably seeks to disavow any direct connection between politics and what it says it is doing in interpreting and applying the law. This is reflected in Latham J’s classic and often quoted assertion that:

the controversy before the court is a legal controversy, not a political controversy. It is not for this or any court to prescribe policy or to seek to give effect to any views or opinions upon policy. We have nothing to do with the wisdom or expediency of legislation. Such questions are for Parliaments and the people.[38]

This is, in effect, an assertion that law is separate from politics. It is a form of reasoning typically described as legalism – that is, the court will decide matters by reference to existing rules and principles, not policy considerations. However, this form of reasoning can be said to be astutely political in and of itself as it seeks to insulate the courts from political controversy by downplaying judges’ ability to make choices when deciding cases.[39] While it is true that judicial methodology provides some important constraints – particularly the appeal system, combined with the duties to apply precedent and to provide a rational explanation of how a decision is reached[40] – it does not mean there is only one correct answer that can be reached. There are inevitably judicial choices that lead to different results. These choices can have significant political consequences. By way of example, how the High Court’s ‘choices’ have impacted federalism and protected certain rights will be briefly considered.

Federalism

The Constitution created a federation with a central federal/Commonwealth government and state governments. To protect the autonomy of the state governments, the Constitution listed specific subjects that the federal parliament could pass legislation on, leaving everything else to the states.[41] The Constitution also allowed the states to continue passing legislation on most subjects allocated to the federal government.[42] However, once there was federal legislation, it was to prevail to the extent that there was any inconsistency with the state legislation.[43]

As the arbiter of the Constitution, the High Court was responsible for determining precisely how the constitutional allocation of power between the federal and state governments would work. In undertaking this task, the High Court, at first, interpreted the Constitution in a way that intentionally favoured the states. But then a choice was made to change course, and the interpretation has favoured the Commonwealth ever since. These choices will be briefly outlined. What will not be addressed – but is worthy of further study – is whether these choices have played a pivotal role in emasculating the powers of the states to an extent unforeseen by the founding fathers[44] or whether they are better understood as reflecting broader historical changes that, in reality, were responsible for the shift in ‘power and authority to the centre of Australian governance’.[45]

The first doctrine or rule developed by the High Court to help explain how power was to be allocated between the federal and state governments was the ‘implied immunity of instrumentalities’. Inspired by USA jurisprudence, this doctrine was based on the notion that each government was sovereign and, as such, neither the Commonwealth nor the states could tell the other what to do unless the Constitution expressly allowed them to do so.[46] This meant, for example, that the states and Commonwealth could not tax each other[47] and a union representative for a state government agency could not be registered under Commonwealth labour laws.[48]

The second interpretative tool developed by the early High Court was the ‘reserved state powers doctrine’. As explained by Blackshield and Williams, this meant that:

the Constitution had impliedly ‘reserved’ to the States their traditional areas of law-making power, and hence that the grants of law-making power to the Commonwealth must be narrowly construed so as not to encroach on these traditional powers of the States.[49]

This doctrine unequivocally favoured the state governments as it was premised on the assumption that the states would continue to be the forum in which the majority of policy decisions were made. Combined with the implied immunity of instrumentalities, it supported the status quo – the status quo at that time being powerful state governments with a federal government largely limited to matters of a genuinely national nature (as the subjects allocated to the federal government in the Constitution were thought to be).

However, the High Court’s early choice to protect the power of the states was not universally popular. After the appointment of further High Court justices and the retirement or death of the three initial judges who had created the two doctrines, a choice was made to interpret the Constitution in a very different way. This choice is most clearly seen in the iconic case of Amalgamated Society of Engineers v Adelaide Steamship Co. Ltd (the Engineers case).[50]

In the Engineers case the High Court rejected the implied immunity of instrumentalities and reserved state powers doctrines. Based on English/Imperial jurisprudence, it chose to view the Constitution as an Imperial statute (which it technically was, having been passed by the Imperial parliament in England) rather than a federal compact. On this view, the Imperial parliament was simply distributing power between the federal and state governments. The governments were not in competition with each other, in the sense that the grant of power to one should not be viewed as diminishing the power of the other.[51] While, strictly speaking, this change in approach did not necessarily favour the federal government, history has shown that it has. This is because the court has generally been willing to read the powers given to the federal government expansively, with the result that the federal government has been able ‘to advance into areas previously held to be within the powers reserved to the state legislatures’.[52] Examples of such advancement include areas where the federal government has been able to rely on its power to legislate in respect of ‘external affairs’ to:

- pass racial discrimination legislation applying across Australia[53]

- stop the building of a dam by the Tasmanian government in Tasmania[54]

- prevent the forestry operations and the construction of roads in Tasmanian forests[55]

- impose throughout Australia a minimum wage, equal pay, unfair dismissal and parental leave.[56]

The federal government has also been able to rely on its power over ‘foreign corporations, and trading or financial corporations formed within the limits of the Commonwealth’ to:

- regulate the trading activities of a corporation even though those activities only occur within one state and even though another power given to the Commonwealth only applies to ‘trade and commerce with other countries, and among the States’[57]

- pass the Workplace Relations Amendment (Work Choices) Act 2005 (Cth), which was intended to apply to up to 85 per cent of the Australian workforce and fundamentally reshape industrial relations in Australia (it was, however, repealed when there was a change of government).[58]

Rights protection

Unlike other English-speaking democracies, Australia does not have a constitutional or statutory bill of rights at the federal level. This omission was intentional. With the exception of a few express protections,[59] Australia’s founding fathers wanted to limit the ability of the courts to interfere with legislative decisions on policy issues, such as, for example, the ability to discriminate on the basis of race as reflected in the since abandoned White Australia policy. Further, the omission of a bill of rights can be said not only to reflect a political decision as to where most policy decisions should be made (the legislature) but also to provide an indication of what type of rights are likely to be protected (those favoured by the voting constituents, who were, at the time of Federation, predominantly white males).[60]

Yet, despite the judgement at Federation that the legislature(s) was primarily responsible for determining the type of rights that were worthy of protection and those that may be compromised for the greater good, decisions of the High Court have nevertheless limited some of the choices available to the legislature. As discussed, the High Court’s interpretation of the Constitution has meant that Australian legislatures are unable to pass legislation that takes away the defining and essential characteristics of the courts. Maintaining these characteristics – such as the court’s ability to provide natural justice or procedural fairness – not only protects the ongoing existence of the courts but also has a derivative effect in that it helps ensure that when a claim is brought before a court, whether by the executive against an individual or an individual against the executive, the individual receives a fair hearing (or at least a base level of fairness).

The courts’ role in enforcing the rule of law and, in particular, ensuring that the executive government complies with the law also saw the High Court at the beginning of the 21st century introduce a new implication derived from the Constitution.[61] That implication was ‘an entrenched minimum provision of judicial review’ over executive decision making. It effectively means that the legislature is unable to pass legislation that prevents the courts from deciding whether the executive has acted within the law. While the implication helps to ensure that the courts continue to operate as part of a system of checks and balances against arbitrary power, it also has the derivative effect of providing a limited form of rights protection. This protection is found in the fact that an individual will ordinarily be able to challenge the legality of any executive decision that is made specifically about them. However, it is a limited protection as the absence of a bill of rights means the legislature can still pass laws that restrict an individual’s substantive rights, making it more likely that adverse executive decisions will be lawful.

Perhaps most controversially, and in what can be termed the second major period of constitutional transformation (after the Engineers case and the cases that immediately followed it),[62] the High Court has more recently found in the Constitution an implied freedom of political communication[63] and an implied right to vote.[64] In effect, the High Court has recognised and enforced a constitutional commitment ‘to certain fundamental freedoms or democratic values’.[65]

The High Court’s commitment to such values has seen it find numerous pieces of legislation invalid. It has, for example, held legislation invalid when it:

- imposed a criminal penalty for publicly criticising the workings of government[66]

- limited political advertising while also establishing a system of free political advertising that favoured the established parties[67]

- prevented prisoners subject to relatively short periods of imprisonment from voting[68]

- reduced the period in which voters could enrol to vote after an election had been called[69]

- capped political donations and limited electoral campaign spending.[70]

However, as interpreted by the High Court, the commitment to freedom of political speech and the right to vote is not without limitations. This is evident in a number of cases where the High Court has chosen not to hold legislation, or the regulations made under legislation, invalid even though political communication or the right to vote was or may have been impeded. The court justified these decisions on the basis that, in the particular circumstances faced, the legislation was a proportionate or ‘appropriate and adapted’ means of achieving legitimate legislative goals. Such goals have included:

- protecting the safety of the public[71]

- enabling electoral rolls to be up to date prior to the opening of polling[72]

- providing limitations on the ability of property developers to make political donations.[73]

Perhaps somewhat ironically, it is in the cases in which legislation has been upheld that the inherently political nature of the High Court’s role in formulating and applying the freedom of political communication and the right to vote is most clear. This is because in applying the ‘appropriate and adapted’ test the High Court judges are openly balancing the policy goals that the legislature has sought to achieve against their own assessment of the effect on, and value of having, an ability to vote or freedom of political communication.

Conclusions

While the courts’ role in Australia can be simply described as interpreting and applying the law, in reality it is far more complex. This complexity is due to the myriad controversies that the courts must adjudicate upon, necessitating a combination of generalist and specialist courts that all sit within a hierarchy in which they are ultimately answerable to the High Court. It is also complex because choices may be made, particularly by the High Court when interpreting the Constitution, that have far reaching repercussions. These repercussions can extend to a change in the balance of power between state and federal governments or the protection of some rights from legislative encroachment.

References

Allan, James, and Nicholas Aroney (2008). An uncommon court: how the High Court of Australia has undermined Australian federalism. Sydney Law Review 30(2): 245–94.

Aroney, Nicolas (2018). Constitutional fundamentals. In Augusto Zimmermann, ed. A commitment to excellence: essays in honour of Emeritus Professor Gabriel Moens. Brisbane: Connor Court Publishing.

Burton Crawford, Lisa (2017). The rule of law and the Australian Constitution. Annandale, NSW: Federation Press.

Crawford, James, and Brian Opeskin (2004). Australian courts of law, 4th edn. Oxford; NewYork: Oxford University Press.

Creyke, Robin, David Hamer, Patrick O’Mara, Belinda Smith and Tristan Taylor (2017). Laying down the law, 10th edn. Chatswood, NSW: Lexis Nexis Butterworths.

Creyke, Robin, John McMillan and Marky Smyth (2015). Control of government action, 4th edn. Chatswood, NSW: LexisNexis Butterworths.

French, Robert (2012). Two chapters about judicial power. Paper presented at the Peter Nygh Memorial Lecture 2012, 15th National Family Law Conference, 15 October.

Galligan, Brian (1987). Politics of the High Court:a study of the judicial branch of government in Australia. St Lucia: University of Queensland Press.

Galligan, Brian, and F.L. (Ted) Morton (2017). Australian exceptionalism: rights protection without a bill of rights. In Tom Campbell, Geoffrey Goldsworthy and Adrienne Stone, eds. Protecting rights without a bill of rights: institutional performance and reform in Australia, 17–39. London: Taylor and Francis.

Gleeson, Murray (2008). The role of a judge in a representative democracy. Judicial Review 9(1): 19–31.

Harvey, Callie (2017). Foundations of Australian law, 5th edn. Prahran, Vic.: Tilde Publishing and Distribution.

Irving, Helen (2009). The Constitution and the judiciary. In R.A.W. Rhodes, ed. The Australian study of politics. Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

Patapan, Haig (2000). Judging democracy: the new politics of the High Court of Australia. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Selway, Bradley, and John M. Williams (2005). The High Court and Australian federalism. Publius: The Journal of Federalism 35(3): 467. DOI: 10.1093/publius/pji018

Stephen, Sir Ninian (1982). Southey memorial lecture 1981: judicial independence – a fragile bastion. Melbourne University Law Review 13(3): 334–48.

Roux, Theunis (2015). Reinterpreting ‘the Mason Court revolution’: an historical institutionalist account of judge-driven constitutional transformation in Australia. Federal Law Review 43(1): 1–25.

Turner, Ryan (2015). The High Court of Australia and political science: a revised historiography and new research agenda. Australian Journal of Political Science 50(2): 1–18. DOI: 10.1080/10361146.2015.1006165

Williams, George, Sean Brennan and Andrew Lynch (2018). Blackshield and Williams Australian constitutional law and theory, 7th edn. Annandale, NSW: Federation Press.

About the author

Grant Hooper has two decades of experience as a litigator. He worked at Phillips Fox Lawyers, which evolved and grew to become part of the international law firm DLA Piper. Grant was a partner at DLA Piper when he left to undertake his PhD in administrative law. Grant taught at the University of New South Wales, Macquarie University and Western Sydney University before joining the University of Sydney Law School. His research interests are in administrative law, public law and torts.

- Hooper, Grant (2024). Courts. In Nicholas Barry, Alan Fenna, Zareh Ghazarian, Yvonne Haigh and Diana Perche, eds. Australian politics and policy: 2024. Sydney: Sydney University Press. DOI: 10.30722/sup.9781743329542. ↵

- Stephen 1982, 338. ↵

- Huddart, Parker and Co. Pty Ltd v Moorehead (1909) 8 CLR 330, 357 (Griffith CJ). ↵

- Australia Act 1986 (Cth), section 9; Australian Act 1986 (UK), section 9. ↵

- Crawford and Opeskin 2004, 21. ↵

- Williams, Brennan and Lynch 2018, 597. ↵

- Huddart, Parker and Co. Pty Ltd v Moorehead (1909) 8 CLR 330. ↵

- Graham v Minister for Immigration and Border Protection [2017] HCA 33, [39]. ↵

- R v Spicer; Ex parte Australian Builder’s Labourers Federation (1957) 100 CLR 277. ↵

- Crawford and Opeskin 2004, 6–7. ↵

- Crawford and Opeskin 2004, 6. ↵

- Creyke et al. 2017, 9. ↵

- Crawford and Opeskin 2004, 23–4; Creyke et al. 2017, 45. ↵

- Williams, Brennan and Lynch 2018, 264. ↵

- This principle is derived from the USA decision of Marbury v Maddison (1803) 1 Cranch 137 and, subject to some modifications, is accepted as ‘axiomatic’ in Australia: see The Australian Communist Party v The Commonwealth (1951) 83 CLR 1, 262 (Fullagar J). ↵

- Section 122 of the Constitution enables the Commonwealth parliament to pass laws allowing for self-government of the territories. ↵

- Kable v Director of Public Prosecutions (NSW) (1996) 189 CLR 51, 138 (Gummow J). ↵

- Harvey 2017, 74. ↵

- Lange v Australian Broadcasting Corporation (1997) 189 CLR 520, 563. ↵

- The Commonwealth parliament has invested state courts with the ability to exercise federal jurisdiction; see in particular section 39 of the Judiciary Act 1903 (Cth). ↵

- R v Kirby; Ex parte the Boilermakers’ Society of Australia (1956) 94 CLR 254, 268. ↵

- Crawford and Opeskin 2004, 40. ↵

- Re Walkim; Ex parte McNally (1999) 198 CLR 511, [200] (Kirby J). ↵

- Crawford and Opeskin 2004, 43. ↵

- Re Walkim; Ex parte McNally (1999) 198 CLR 511. ↵

- Aroney 2018, 1. ↵

- Burton Crawford 2017, 10–11. ↵

- Graham v Minister for Immigration and Border Protection [2017] HCA 33, [46]. ↵

- Creyke, McMillan and Smyth 2015, 313. ↵

- Act of Settlement 1701 (UK). ↵

- R v Kirby; Ex parte the Boilermakers’ Society of Australia (1956) 94 CLR 254. ↵

- Clyne v East (1967) 68 SR (NSW) 355. ↵

- Kable v Director of Public Prosecutions (NSW) (1996) 189 CLR 51. ↵

- French 2012, 5. ↵

- French 2012, 5. ↵

- Irving 2009, 116, describing observations of Galligan 1987, 1. ↵

- Turner 2015, 358–9. ↵

- South Australia v The Commonwealth of Australia (1942) 65 CLR 373, 409. ↵

- See Williams, Brennan and Lynch 2018, 172. ↵

- Gleeson 2008, 25–6. ↵

- See in particular sections 51, 52, 106, 107 and 108 of the Constitution. ↵

- Some subjects are exclusively Commonwealth, such as those set out in section 52. ↵

- See section 109 of the Constitution. ↵

- Allan and Aroney 2008. ↵

- Selway and Williams 2005. ↵

- Attorney-General (NSW) v Collector of Customs for NSW (1908) 5 CLR 818 (Steel Rails). ↵

- Baxter v Commissioners of Taxation (NSW) (1907) 4 CLR 1087; D’Emden v Pedder (1904) 1 CLR 91; Deakin v Webb (1904) 1 CLR 585. ↵

- Federated Amalgamated Government Railway and Tramway Service Association v New South Wales Railway Traffic Employees Association (1906) 4 CLR 488 (Railway Servants’). ↵

- Williams, Brennan and Lynch 2018, 280. ↵

- Engineers (1920) 28 CLR 129. ↵

- Selway and Williams 2005, 480. ↵

- Selway and Williams 2005, 480. ↵

- Koowarta v Bjelke-Petersen (1982) 153 CLR 168. ↵

- Commonwealth v Tasmania (1983) 158 CLR 1 (Tasmanian Dam). ↵

- Richardson v Forestry Commission (1988) 164 CLR 261. ↵

- Victoria v Commonwealth (1996) 187 CLR 416 (Industrial Relations Act). ↵

- Strickland v Rocla Concrete Pipes Ltd (1971) 124 CLR 468. ↵

- New South Wales v Commonwealth (2006) 229 CLR 1 (Work Choices). ↵

- Such as sections 80, 92 and 116 of the Constitution. ↵

- Galligan and Morton 2017. ↵

- Plaintiff S157/2002 v Commonwealth of Australia (2003) 211 CLR 476 (Plaintiff S157). This implication was extended to state Supreme Courts in Kirk v Industrial Court of New South Wales (2010) 239 CLR 531. ↵

- Roux 2015, 1. ↵

- Australian Capital Television Pty Ltd v Commonwealth (1992) 177 CLR 106; Nationwide News Pty Ltd v Wills (1992) 177 CLR 1. ↵

- Roach v Electoral Commissioner (2007) 233 CLR 162. ↵

- Williams, Brennan and Lynch 2018, 1328. See also Patapan 2000. ↵

- Nationwide News Pty Ltd v Wills (1992) 177 CLR 1. ↵

- Australian Capital Television Pty Ltd v Commonwealth (1992) 177 CLR 106. ↵

- Roach v Electoral Commissioner (2007) 233 CLR 162. ↵

- Rowe v Electoral Commissioner (2010) 243 CLR 1. ↵

- Unions NSW v New South Wales (2019) HCA 1; Unions NSW v New South Wales (2013) 252 CLR 530. ↵

- Levy v Victoria (1997) 189 CLR 579. ↵

- Murphy v Electoral Commissioner (2016) 334 ALR 369. ↵

- McCloy v New South Wales (2015) 257 CLR 178. ↵