52 Accountability

Diana Perche

Key terms/names

accountability, administrative review, corruption, integrity, judicial review, ministerial responsibility, responsibility, rule of law, separation of powers, Westminster

Introduction

Accountability is at the very centre of democracy.[1] Given democracy is about ‘rule by the people’, it is vital for citizens to know what their government is doing, to be able to call the government to account for what it has done or decisions it has made and also be able to direct the government to take certain actions if required. Once chosen by the people, governments have access to considerable power over the rest of us. There are clear dangers associated with this: power can be abused, corrupted and used for the wrong ends. In a democracy, we should be able to limit and curtail this power.

The most obvious way of limiting government power in a democracy is through a system of free and fair elections, which provide voters with a regular opportunity to assess the performance of the political party in government and make a deliberate decision about whether to allow them to continue in office or to allow another party to take over. But electoral accountability is flawed: elections are infrequent, and voters have many considerations when selecting their preferred candidate, including the appeal of election promises, party leadership and local issues.[2] The relationship between the people and their government therefore needs more than just elections to ensure that the people can call their government to account.

Another important feature of a liberal democracy is the doctrine of the separation of powers: that is, the understanding that the three branches of government are designed to perform different functions and provide a check on the power of the others. Thus, it is the role of the parliament or legislature to limit the power of the executive (the ministers and the public servants supporting them). This is somewhat more complicated in a Westminster system, which ‘fuses’ the executive and the legislature by drawing ministers from the elected parliament, and allows for an especially dominant executive in a two-party system,[3] as we shall explore. The clearest separation is with the third branch, the judiciary, which has a role to play in protecting citizens according to the rule of law, in resolving disputes and undertaking judicial review of administrative decisions.

Australian scholar John Uhr reminds us that ‘[d]emocracy certainly needs large doses of trust between electors and their representatives, but it also benefits from doses of distrust’.[4] Governments have clear obligations to maintain high standards of public conduct, and to earn the trust of the electors. At the same time, it is up to citizens to constantly question their governments, because it is the nature of government, and politics, that abuses of power, corruption and slippery application of the law will occur. Promises will be broken, mistakes will be made and opportunities will be seized – and the public interest will not always be uppermost in the minds of those making decisions.

It is for this reason that we need a range of external methods of accountability that extend beyond regular elections. Our Westminster system of responsible government is based on the doctrine of ministerial responsibility, but we also rely on a wide range of watchdogs, independent observers, avenues of review and appeal, codes of conduct and, perhaps most importantly, information being made public about what governments are doing and how they are making their decisions. This chapter explores this web of accountability mechanisms and consider the theoretical and political context in which they work to protect the public. We will focus on the national government in Canberra, though most of the features discussed in this chapter also apply at the state level. First, we will define some key concepts.

Accountability and responsibility

Responsibility and accountability are often used interchangeably with respect to public decision making, and both imply that an actor has been charged with carrying out a specific task, and is answerable for their actions or decisions. For example, a public servant might be responsible for determining eligibility for a pension, and will be called to account if they make the wrong decision or fail to make a decision.

Richard Mulgan differentiates between responsibility, which he sees as referring to ‘internal aspects of action’ in the sense of individuals exercising judgement about how they act with respect to their duties and obligations, and accountability, which relies on ‘external scrutiny from someone else’.[5] Accountability is thus provided for in procedures, rules and legislation, and is enforced. Accountability is based on a relationship of rights and obligations, where ‘government members are induced to explain or justify their actions or to engage in debate and discussion with interested parties.’[6] Furthermore, Mulgan insists that there must be actual consequences and remedies for wrongdoing or incompetence: ‘[a]ccountability is incomplete without effective rectification’.[7]

Bovens observes that the word ‘accountability’ is often used in a normative sense, as a personal ‘virtue’, or a standard against which the behaviour of public officials might be measured. By contrast, an institutionalist perspective would consider ‘accountability’ as a mechanism to retrospectively seek information, pass judgement and if necessary impose sanctions with respect to the actions of a public official.[8] In this sense, the existence of the accountability mechanism may influence the behaviour and choices of those public officials who might anticipate negative attention, and it may contribute to the legitimacy of the institution overall. This is the sense in which accountability is most often understood in a public policy context, where the focus then is on describing the mechanisms within a given institutional setting.

The social and political context in which accountability is managed becomes clearer in an influential work by American scholars Dubnick and Romzek. These authors offer the following definition:

Public administration accountability involves the means by which public agencies and their workers manage the diverse expectations generated within and outside the organisation’.[9]

They map out a typology of accountability systems that varies according to institutional context, level of technical expertise involved, and the extent to which external control of the agency is possible. These are illustrated in Table 1.

|

|

Internal control |

External control |

|---|---|---|

|

High degree of control over agency |

Bureaucratic |

Legal |

|

Low degree of control over agency |

Professional |

Political |

This typology helps to explain why some actions by public officials receive very little public attention, due to their technical complexity or strong internal controls, while others are habitually highlighted by the media or political opponents, and are highly politicised.

These different approaches point to the ways in which accountability is both internalised and externally managed. The critical factor is that public actions should be open to scrutiny and public officials should be required to respond. There are numerous cases where governments are questioned or exposed to criticism, but manage to escape the requirement to explain their actions or to engage in debate with those who are affected. The media raise a number of these cases, as do parliamentarians, courts and formal inquiries. Even when accountability mechanisms are present, they may not be sufficient, because power and politics may intervene.[11] Ultimately this can have a profound impact on the level of trust in government, and the health of the democracy, if ministers and public servants appear to serve their own interests rather than the public interest.

This is already a discernible risk in Australia. Satisfaction with democracy among voters has fallen from a high point of 86 per cent of voters being satisfied in 2007 to just 59 per cent in 2019.[12] Over the same period, respondents reporting the view that ‘people in government look after themselves’ increased from 57 per cent to 75 per cent.[13] Furthermore, the international anti-corruption think tank and advocacy organisation Transparency International has reported that Australia has fallen over the last decade from being ranked 11th to 18th in the world on the global Corruption Perceptions Index, in large part due to the lack of attention to political donations and the government’s poorly regulated exposure to powerful lobbyists.[14] Australians cannot be complacent about the health of their democracy: when good government fails, the impact can be felt by individuals, organisations and communities. We shall now turn to the formal mechanisms as they are designed and applied at the federal level in Australia.

The Westminster parliamentary system and responsible government

In a Westminster parliamentary system such as Australia’s, the parliament plays a significant role in holding the elected government to account, on behalf of the people, in a system known as responsible government. The parliament enacts legislation, subjecting it to scrutiny and debate on behalf of constituents, and authorises all government financial activities. Parliamentary activities, including debates, votes, ministerial questions and answers, committee inquiry submissions, hearings and reports, and tabled documents, are all placed on the public record, in particular through the edited transcripts known as Hansard, and reported by the media.

The most readily observable feature of responsible government in action is the part of every parliamentary sitting day where members of parliament are allowed to ask questions of the government ministers, in both the House of Representatives and the Senate, in a session known as Question Time. Questions are alternated between the opposition, government and crossbench, and ministers are expected to respond to questions about their own portfolio immediately. Members of the opposition will try to use their questions to embarrass the government; government members are more likely to ask gentler questions (known as Dorothy Dixers) that will allow the minister to discuss the government’s performance in a positive light. Question Time has received much criticism in recent years for its adversarial atmosphere, the emphasis on point scoring and outrage rather than enlightened sharing of information, and the lack of respect by parliamentarians for the important accountability function it serves.[15]

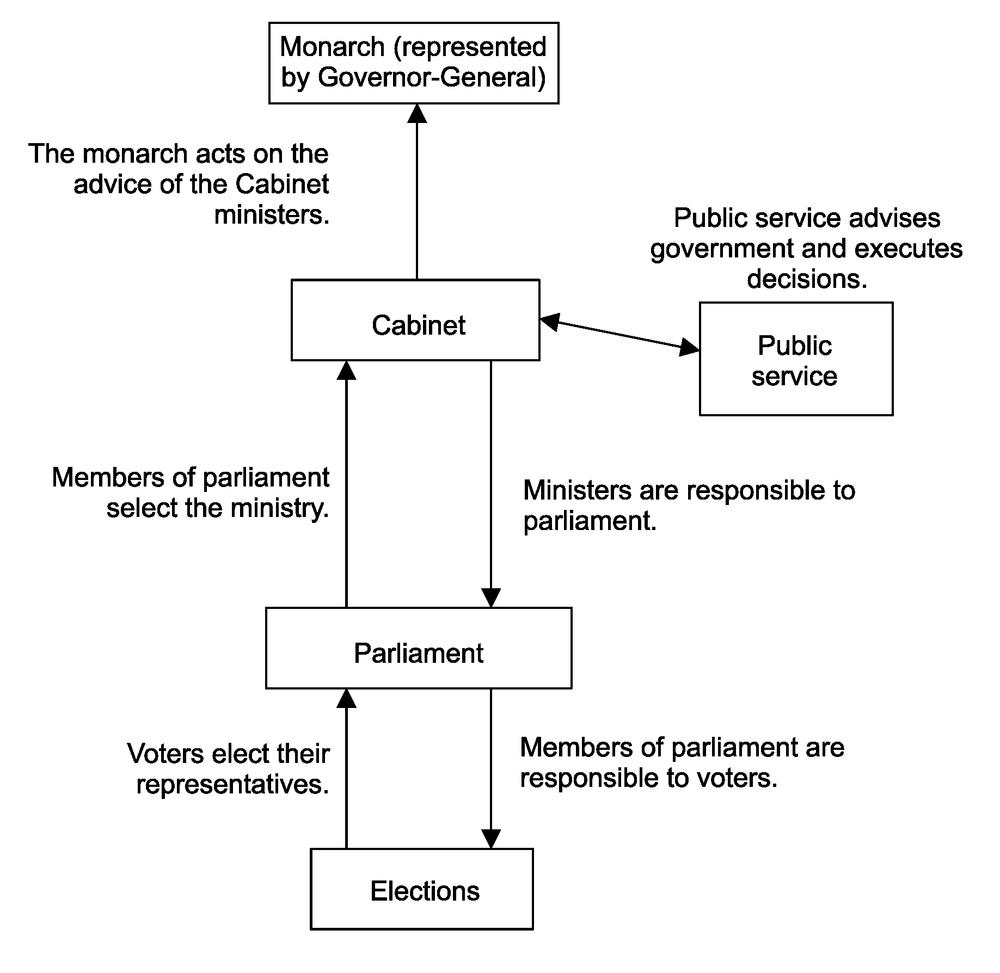

The chain of accountability relies on ministerial responsibility. Ministers are elected members of parliament, and it is the parliament (through the choices of the party with the majority in the lower house) that determines the ministers who form the Cabinet. These ministers are answerable to parliament for the actions of the public service working under their ministerial direction. The parliament in turn is answerable to the people who voted for their representatives at an election. This relationship is shown in Figure 1.

There are nuances to the concept of ministerial responsibility. Patrick Weller observes that ministers have three distinct relationships of responsibility:[16]

- Personal behaviour: Ministers are responsible to the prime minister for their own actions, including the ways in which they manage potential conflicts of interest, and any embarrassment they might cause the prime minister or the government through unethical behaviour or misjudgement.

- Collective behaviour: Ministers are responsible for their collective behaviour as members of Cabinet. This means that ministers are expected to publicly support Cabinet decisions, whether or not they agreed with them during the confidential debate around the Cabinet table. By convention, if a minister does not agree with a Cabinet decision, they are expected to resign (though they may be more likely to put up with the decision and retain the benefits of being part of the government). In the spirit of collective responsibility, ministers are also expected to avoid speaking about issues outside their own portfolio, for fear of sending mixed messages.

- Administrative behaviour: Ministers are understood to be responsible for administrative behaviour: that is, for their departments. In practice, this means that they must answer questions about their portfolio in parliament, and they are held accountable for their own personal actions or decisions as minister, but they are not usually understood to be responsible for the actions of officials within their departments. Instead, they might be more commonly expected to fix the situation once a problem has been uncovered.

Ministers do occasionally lose their jobs because of breaches of ministerial responsibility, though this is more often due to the political damage caused by a breach of ministerial standards as determined by the prime minister than due to incompetence or poor performance in the portfolio. In one recent example, Sussan Ley, health minister under the Coalition government of Malcolm Turnbull, was stood aside after media reports that she had misused her parliamentary travel entitlements, using a ministerial visit to the Gold Coast to purchase real estate.[17] The minister for sport, Bridget McKenzie, was removed from her position by Prime Minister Scott Morrison when it was determined that she had a conflict of interest and had not declared her membership of a rifle club that received government funds. Notably, the broader issue of her office allocating grants to sporting organisations on the basis of the government’s electoral interests, rather than merit, was not seen as a sufficient reason to resign, despite a negative report from the auditor-general.[18] The key point here is that these are political decisions, made by the prime minister, and personal loyalties, factional ties and short-term electoral prospects may ultimately be more persuasive than respect for the convention of ministerial responsibility.[19] Each prime minister develops a guide to expectations of their ministers, and will interpret and apply these according to their own political imperatives as needed.[20]

A critical factor in Australia’s Westminster system is the dominance of the executive, given the power of the prime minister and Cabinet to control the parliamentary agenda and processes. As long as the government has the numbers in the House of Representatives, there is little that the opposition or other parties can do to challenge the legislative agenda. The party with the majority chooses the Speaker, who enforces the rules of debate and the Standing Orders governing parliamentary procedures, and they can also choose to limit the time allocated to a debate, or vote to silence a member.[21] Votes of censure or no confidence against the government are unlikely to succeed as the government tends to have a majority in the lower house, and this has clear implications for responsible government. Australia has a tradition of very strong party discipline, which means that the two major parties can rely on tightly managed votes on the floor of parliament, and the prospect of party members crossing the floor to vote against their own party is rare. The powerful influence of party politics over parliamentary activity has prompted scholars to refer to the Westminster system as being one of ‘responsible party government’ rather than ‘responsible government’.[22] Where members of parliament are primarily motivated by loyalty to their own party, the political interests of the party can come a distant second to the public interest in good government.

The Senate is rarely dominated by the party in government and can thus deploy a range of mechanisms to scrutinise government decisions and performance.[23] In order to pass legislation, the government may need to negotiate with the opposition, or with the minor parties and independents on the crossbench who hold the balance of power, and in doing so the proposed Bill may be subjected to critical attention and compromises resulting in amendments. For example, the Albanese Labor government passed its Climate Change Act in 2022 setting a binding target of reducing carbon emissions by 43 per cent by 2030 with the support of some of the crossbench, after accepting amendments aimed at increasing transparency in reporting carbon emissions that were proposed by the independent Senator David Pocock.[24]

In rare cases, the Senate can censure a minister for impropriety, not declaring a conflict of interest or misleading the Senate. For example, senators censured the Coalition minister for aged care, Richard Colbeck, in September 2020, for failing to take responsibility for the crisis in residential aged care facilities during a severe COVID-19 outbreak in Victoria.[25] Censure motions have led to ministerial resignations in the past, but in this case, the then Prime Minister Scott Morrison chose to ignore the censure, protecting his minister.

The most significant accountability mechanism used by the Senate is the committee process. Committees are formed around portfolio areas, and members are drawn from all parties, reflecting the numbers a party has in the Senate. Committees are responsible for holding inquiries into proposed legislation or specific issues referred to them by the Senate as a whole, and also conduct routine hearings twice a year known as Estimates, where they examine the performance of the executive branch (the ministers and senior members of the public service) and consider proposed government expenditure in the government’s proposed Budget. Committees have wide-reaching powers to collect evidence, including the power to summon witnesses, require them to produce documents and to give evidence under oath. Committee inquiries usually call for submissions from the public, and will invite witnesses to appear at hearings, either in Canberra or a committee may also travel to affected communities. Most committee hearings occur in public and proceedings are transcribed and published (with some exceptions usually due to national security).

It is the transparency of public hearings and the access to information directly from public officials that makes Senate committees so powerful as accountability mechanisms. The reports delivered by the committees after an inquiry is completed may have little influence over the government when it comes to accepting or acting on the recommendations, particularly if the dominant voices in the report are those from the opposition and crossbench. Reports delivered by Senate committees are often bipartisan, showing the extent to which consensus can be reached outside the adversarial parliamentary chamber. For more controversial reports, a dissenting report may be prepared and placed on the parliamentary record. One such example is the Senate committee inquiry into the treatment of Christine Holgate, the CEO of Australia Post who was forced to resign after rewarding high-performing staff with gifts of luxury watches. The committee was chaired by Greens Senator Sarah Hanson-Young and dominated by senators from minor parties and Labor. The report was very critical of the government for failing to treat Holgate with procedural fairness, and called for the prime minister to apologise for his treatment of Holgate, and for the chair of the Australia Post board to resign. A dissenting report prepared by Coalition committee members defended the government’s actions as well as the behaviour of members of the Australia Post board, and the government did not formally respond to the report.[26]

The auditor-general is an integrity agency that focuses on government finances and probity, examining government expenditure and looking for evidence of corruption. More recently, the Australian National Audit Office (ANAO) has also focused on auditing performance, with an emphasis on efficiency and effectiveness of government service delivery. The auditor-general is an institution adopted from Westminster that dates back to the 1860s in England, and was established by the Australian parliament soon after Federation.

There is a very close relationship between the auditor-general and parliament, through the parliamentary Joint Committee of Public Accounts and Audit. This is a practical manifestation of the role of parliament in approving all government expenditure through the annual budget and the related reporting requirements by which the parliament ascertains that the previous year’s expenditure was spent in accordance with the parliament’s wishes. In addition to the Senate Estimates committee process, the reports from the auditor-general bring highly specialised financial and accounting expertise in scrutinising government activity. Reports are tabled in parliament and are reviewed by the Joint Committee of Public Accounts and Audit, in a process that includes holding public hearings, and taking evidence from officers of the agencies that were the subject of the reports. Parliamentary committees and individual members of parliament can also recommend an audit be conducted into a particular issue that comes to their attention. An example of this is the performance audit that prompted the accusations of infrastructure pork barrelling after the 2019 election, the Administration of Commuter Car Park Projects within the Urban Congestion Fund,[27] which was prompted by the ANAO’s own work plan but also requested by a member of the opposition, Andrew Giles MP, as well as the Joint Committee of Public Accounts and Audit, and the Rural and Regional Affairs and Transport Reference Committee.

The auditor-general’s independence of the executive is protected in legislation, but it nevertheless depends on the government of the day for its funding. During the last decade under the Coalition government, the ANAO experienced annual budget cuts, and the auditor-general noted these publicly and observed that the reduced funding directly affected the number of performance audits that the agency could carry out each year.[28] As some critics have observed, establishing a guaranteed funding commitment is essential to the ANAO’s independence and its role in supporting the parliament and the public in holding the government to account.[29]

As we have seen, the Westminster parliamentary system is built around accountability through responsible government, but the dominance of the executive can inhibit true accountability. The party in government with a secure majority can control outcomes, and parliament itself can sometimes appear to be little more than a ‘rubber stamp’. This points to the need for other accountability mechanisms to protect the rights and interests of citizens and those affected by government actions.

Judicial review

In a democracy, the rule of law means that everything, including all actions taken by government, must be done in accordance with the law. An individual who is adversely affected by the actions of an administrator or an administrative body can challenge the action in the courts, and it is the role of the judiciary to determine the legality of the behaviour of the executive.[30] This is known as judicial review. As Justice Brennan succinctly defined it in the High Court case of Church of Scientology v Woodward in 1982:

Judicial review is neither more nor less than the enforcement of the rule of law over executive action; it is the means by which executive action is prevented from exceeding the powers and functions assigned to the executive by law and the interests of the individual are protected accordingly.[31]

Judicial review does not apply to the functions and decision-making powers of parliament in passing legislation, but rather focuses on the particular administrative actions and cases where the legislation is applied to individuals. These are the decisions made by public servants when determining individual claims for pensions, benefits, grants, tax returns, licences and so on. Judicial review is not the same as an appeal. It is focused on legality, thus looking at the process and procedure by which the decision was reached, and the powers granted to the decision maker to exercise discretion in making the determination. By contrast, a ‘review on the merits of the case’ would look at the evidence presented to the decision maker, and determine questions of fact rather than questions of law. If the judicial review body does find flaws in the decision-making process, they cannot substitute their decision for the original, but must ‘set the decision aside’, effectively sending it back to the original decision maker to reconsider.[32]

The High Court’s jurisdiction is entrenched in section 75 of the Constitution, and cannot be removed or limited by the parliament without a referendum. The jurisdiction of lower federal courts is allowed under the Administrative Decisions (Judicial Review) Act 1977 (Cth) which essentially codified in plain English the common law grounds for judicial review of decisions made under federal law. Similar legislation applies in most states. The two most important common law grounds on which a court can ‘set aside’ an administrative decision are the denial of natural justice (or procedural fairness) and ultra vires (where an action is beyond the authority of the decision maker). We shall look at each of these briefly in turn.

Natural justice focuses on providing an individual with the right to a fair hearing in a case that adversely affects them. This means that they must be given prior notice of the allegations or intended action, they must be shown the material used in evidence, and they must have a reasonable opportunity to present their own case. The decision maker must also ensure impartiality and avoid any perception of bias in their approach to the case. In one recent example that received international attention, professional tennis player Novak Djokovic was released from immigration detention after the court found he had not been allowed enough time to respond to the notification by border officials at Melbourne airport that his visa would be cancelled, on the basis that he had not been vaccinated for COVID-19: a breach of procedural fairness.[33] Djokovic was subsequently forced to leave Australia without playing at the Australian Open tournament after the minister for immigration cancelled his visa on character grounds.

Ultra vires protects against the abuse or misuse of power, where a decision may be found to have been unreasonable, inflexible, unauthorised, made for an improper purpose or has taken into account irrelevant considerations. A famous ultra vires case brought by the Northern Land Council on behalf of the Larrakia people, traditional owners of the Cox Peninsula area outside Darwin against the Northern Territory Administrator in 1981, found that town planning regulations to expand the defined area of town land around Darwin from 142 square kilometres to 4350 square kilometres were invalid because they were not applied for the proper purpose of town planning, but rather the improper purpose of attempting to prevent a land rights claim.[34]

There are certainly barriers – including time limits, questions of standing (or recognised interest in the case) and expensive court costs – that can prevent some organisations and individuals from accessing judicial review. Courts have also refused to assess matters of national security, foreign affairs, decisions made by the governor-general or decisions made by Cabinet, as these are political, not administrative, decisions. For most cases where an individual is adversely affected by an administrative decision, the more commonly accessed accountability mechanism is an appeal under administrative law.

Administrative law and merit review

As we have observed, there are distinct weaknesses in parliamentary accountability mechanisms, and the power of the judiciary to provide checks and balances to executive power is somewhat constrained. In the late 1960s and 1970s in Australia, this led to the development of a reform agenda around what was then known as ‘new administrative law’. This was a democratic response to the changing expectations of the electorate, at a time when civil and human rights were prominent on the international stage, the welfare state had expanded its reach into many aspects of citizens’ lives, and citizens demanded better access to public information and were less accepting of government secrecy, particularly around the Vietnam War.[35] The reform package focused on providing a wider range of accountability mechanisms, including expanding the scope of review of administrative decisions beyond the narrowly defined judicial review, simplifying the process of judicial review and increasing its accessibility, and providing better public access to government-held information.

The Administrative Decisions (Judicial Review) Act 1977 introduced a new court, the Federal Court, which was given jurisdiction to undertake judicial review of Commonwealth decision making. The Act also streamlined the procedure for seeking judicial review and codified the common law grounds for review. Another important aspect of the Act was the provision for any individual to obtain a statement of reasons for the administrative decision that affects them, including disclosure of the evidence on which the administrative body based its decision.[36] This engendered a profound cultural change in the public service, and it became standard for almost all routine, high-volume decision-making at the primary level to include a statement of reasons for decision, and in most cases, also information about the rights the individual has to have the decision reviewed and how to go about accessing such a review.

This was accompanied by legislated mechanisms for review of administrative decisions. For most Commonwealth agencies, the first level of review is an internal review of a decision, conducted by a senior delegate within the same agency. As part of the new administrative law reform package, a new set of tribunals was created to provide a low-cost path to a next level of review by an external party. The key body in this area is the Administrative Appeals Tribunal (AAT), established in 1975.[37] This is not a judicial body, with the restrictions of judicial review, but is an administrative body that has the executive power to review a decision on its merits, reconsider the findings of fact on which the decision was based, and ultimately make its own independent assessment of the case which replaces the original decision. Access to this level of administrative review is allowed under the administrative agency’s own legislation.

AAT hearings are designed to be informal and relatively quick, and accessible at low cost. Fees do not apply for cases brought by veterans, social security beneficiaries, National Disability Insurance Scheme recipients, students, health concession cardholders and applicants showing evidence of financial hardship. The AAT is not bound by strict rules of evidence, as a court would be, and can use mediation and alternative dispute resolution processes where appropriate, but it is bound by rules of procedural fairness. If a party is not satisfied with the decision made by the tribunal, an appeal may be made to the Federal Court of Australia on a question of law only, as there is no further right to review on the merits of the case.

The Ombudsman was established by legislation as part of the new administrative law reforms in 1976 at the Commonwealth level.[38] The role of the Ombudsman is to investigate complaints about public or government agencies and their administrative action on behalf of individual citizens, rather than respond to requests for intervention by the parliament. It offers a different form of external scrutiny of administrative decision making that does not fit easily into the mechanisms of judicial or merit review. The Ombudsman can conduct investigations on a case-by-case basis as requested by individuals, or can combine investigations where a large number of complaints have been made. The Ombudsman can also initiate their own investigations. Their processes are designed to be informal and low profile, confidential and free of charge for the complainant. For most investigations, there is no public report at the end, and many investigations are resolved quickly at a preliminary stage, with the Ombudsman’s office playing the role of mediator between the complainant and the agency. Where necessary, the Ombudsman has the power to examine witnesses under oath, inspect government premises and require information to be produced, within the bounds of procedural fairness. They may make recommendations to the agency in question: for example that the agency make an apology, change its decision, amend its rules and procedures, or pay compensation – but these reports are essentially opinions and are not binding. Where the agency fails to take the appropriate action, in the view of the Ombudsman, a report can be made to the prime minister, and even more rarely to parliament.

The value of the role of the Ombudsman is in the capacity to intercede on behalf of citizens and hear individual complaints. As the New South Wales Ombudsman observed in a report delivered into the state governments’ crisis response to COVID-19 in 2020, the effective handling of complaints can help to foster transparency, build confidence and trust in government agencies, improve customer satisfaction and also contribute to better policy making overall.[39]

The appeal and complaints mechanisms created as part of the new administrative law agenda cater for individuals bringing their grievances about specific cases to the attention of independent actors who have the power to examine the internal decision making of government. This provides a critically important channel for scrutiny of executive action for individuals. Accountability also relies on the public having access to information about government action more broadly, as we explore in the next section.

Information, disclosure and public scrutiny

Accountability in a democracy depends on a healthy flow of information between citizens and their government, in both directions. In modern representative democracies, with large populations represented by often remote governments, we rely heavily on the media to inform the public about the activities of government, and represent the opinions of the public back to elected representatives. This notion has been developed into an understanding of the media as being a political institution in its own right, sometimes dubbed the ‘Fourth Estate’. Shultz provides a critical analysis of the way in which the media can play this role, observing:

Of the institutions which emerged to provide checks and balances, to ensure that the political system was subject neither to the arbitrary authority of a capricious monarch, nor the tyranny of the majority, the press was the only one whose survival depended on, and was measured by, commercial success.[40]

The drive for audiences and advertising revenue can certainly complicate the ‘watchdog’ role of the media in holding powerful actors to account, as can the co-dependent relationship between the media and politicians.[41] The government will often seek to use the media to suit its own interests, but also finds ways to avoid unwanted scrutiny.

The principle of open and transparent government was an important feature of new administrative law and it was enshrined in legislation federally in the Freedom of Information Act 1982, with similar models following in the states over the next decade. The legislation frames government transparency as critical to representative democracy as it allows for scrutiny of government activities and fosters better-informed decision making by increasing public participation.[42] The Act provides a mechanism for individuals to request access to information held by the government about themselves, in departmental files. This is often useful for applicants who wish to make a claim for benefits or apply for a visa, for example, or who want to appeal an administrative decision. In terms of accountability, Freedom of Information (FOI) is often used for more general requests about government policy and practice by journalists, academics and other stakeholders, including politicians. The agencies holding the information charge fees in most cases for processing FOI requests, and can refuse to release specific kinds of information.[43] The impact of new technology, including electronic databases and communication instead of paper files, is not yet reflected in the legislation.[44]

In recent years, the federal government has been widely criticised for its lack of respect for the FOI Act and the transparency it demands, as it applies exemptions and refuses to release information, and fails to allocate sufficient priority to the FOI function. Under the legislation the government may refuse access to documents that are subject to commercial confidentiality or Cabinet confidentiality, or documents that are considered ‘working documents’ that have the status of advice only. One report by the Office of the Australian Information Commissioner into the Department of Home Affairs in 2019, for example, noted that over half of the requests for non-personal information were not finalised within the prescribed timeframe, due to a lack of resources in the FOI section of the department.[45] More recently, the Morrison government was criticised for refusing to release documents used by the National Cabinet (the intergovernmental meeting of the prime minister, state premiers and territory chief ministers) during the COVID-19 pandemic. This was publicly challenged by crossbench Senator Rex Patrick, and his appeal to the AAT found against the government; nevertheless the government insisted that the body is a subcommittee of the federal Cabinet and thus subject to Cabinet confidentiality.[46]

The role of whistleblowers is often significant in helping to bring key information to public attention. Whistleblowers are employees of an organisation who choose to report information about illegal or improper practices to an external body (such as the media), to bring about some form of action or accountability.[47] As Mulgan observes, this kind of disclosure presents a dilemma for public servants, who are expected to protect government secrecy and observe internal protocols, yet may be genuinely concerned about the ‘public’s right to be informed’.[48] Under the Commonwealth’s Public Service Act 1999, breaching government confidentiality goes against the Code of Conduct, and it is also an offence under the Crimes Act 1914. Federal and state governments in Australia have developed complex legislation around ‘protected disclosures’ or ‘public interest disclosures’, designed to protect public servants who make disclosures in specific circumstances from reprisals or disciplinary processes. A number of prominent whistleblower cases in recent years reveal the extent to which governments will pursue what they see as inappropriate disclosure of sensitive information, notably including the cases of David McBride and the Department of Defence, Richard Boyle and the Australian Tax Office, and the pursuit of ‘Witness K’ and his lawyer Bernard Collaery by the Australian Secret Intelligence Service.[49]

Integrity agencies and accountability

As we observed at the start of this chapter, accountability is fragile, and needs to be both internalised and externally managed. Scholars considering government accountability in the 1990s and early 2000s recognised that protection against corruption relies on ‘the institutionalisation of integrity through a number of agencies, laws, practices and ethical codes’.[50] They emphasise the need for multiple mechanisms of accountability, in a diffused, fragmented structure, with overlap, duplication and shared functions built in. They use the image of a ‘bird’s nest’ to describe the integrity system, recognising that each twig on its own is insufficient, but that the combination of all the overlapping agencies and mechanisms ensures that if one fails, government integrity is still secure.[51]

We have already considered the role of the auditor-general and the ombudsman, both prominent and powerful integrity agencies with clearly defined roles. There are many others, some with very narrow remits, such as the Australian Commission for Law Enforcement Integrity, or the Inspector-General of Intelligence and Security.[52] Each of these agencies relies on different pieces of legislation, which determines their mandate to investigate cases, their investigative powers, whether their inquiries are held in public or private, and who receives the report at the end of the process. The recruiting practice for staff and the funding arrangements may have a significant effect on the independence and impartiality of these agencies.[53]

Public debate in recent years has focused on the need for a national anti-corruption commission as a new element in the integrity system. All Australian states already have their own anti-corruption commissions, following slightly different models. These agencies generally have very strong investigative powers, and many hold public hearings. In this sense they are much like royal commissions, which are seen as exceptional accountability mechanisms with substantial investigative powers combined with intense media scrutiny.[54] The critical limitation of royal commissions is that they are created for a specific purpose by governments, usually under pressure, and the government chooses the terms of reference, the identity of the commissioner, and the timeframe they are allowed for their inquiry. A standing anti-corruption commission plays a significant role, then, not just in making findings of corruption, but in changing the political culture through education and permanent profile. Anti-corruption commissions can be devastating to some governments and individuals, as the resignation of the New South Wales Premier, Gladys Berejiklian, in 2021 illustrated.[55] The recently elected Albanese government promised to establish a federal anti-corruption body during the election campaign, and passed legislation with bipartisan and crossbench support at the end of 2022, adopting many of the key features of state bodies.[56]

Conclusion

We have considered the many different mechanisms that are used in Australia for holding the government to account. Australia has a complex structure of integrity agencies, courts, parliament and tribunals providing oversight and review, and investigating corruption and other forms of maladministration. This bird’s nest of overlapping twigs and branches is required to ensure government integrity. As the infamous Robodebt case showed, one agency alone was not enough to put a stop to a poorly designed and illegal debt-collection scheme: repeated appeals to the AAT, a review by the Federal Court, parliamentary inquiries and an investigation by the Ombudsman all combined to put pressure on the government, and a Royal Commission is now underway.[57] Governments will continue to avoid sharing information or admitting mistakes, but it is up to members of parliament, the media and ordinary citizens to remain vigilant and demand full accounting and rectification where it is necessary, and not settle for mere normative aspirations.

References

ABC News (2021). Gladys Berejiklian resigns as NSW Premier after ICAC probe into her relationship with Daryl Maguire announced. ABC News, 1 October. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2021-10-01/icac-investigating-gladys-berejiklian-daryl-maguire/100506956.

Australian National Audit Office [ANAO] (2020). ANAO Annual Report 2019–20. Canberra: Commonwealth Government. https://www.anao.gov.au/work/annual-report/anao-annual-report-2019-20.

Australian Public Service Commission. (2021). Fact sheet: defining integrity. Canberra: Commonwealth Government. https://www.apsc.gov.au/working-aps/integrity/integrity-resources/fact-sheet-defining-integrity.

Bovens, Mark (2010). Two concepts of accountability: accountability as a virtue and as a mechanism. West European Politics 33(5): 946–67. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2010.486119.

Brown, A.J. (2019). From Richard Boyle and Witness K to media raids: it’s time whistleblowers had better protection. The Conversation, 13 August. https://theconversation.com/from-richard-boyle-and-witness-k-to-media-raids-its-time-whistleblowers-had-better-protection-121555.

Brown, A.J. (2022). Australia’s national anti-corruption agency arrives. Will it stand the test of time? The Conversation, 30 November. https://theconversation.com/australias-national-anti-corruption-agency-arrives-will-it-stand-the-test-of-time-195560.

—— and Brian Head (2005). Assessing integrity systems: introduction to the symposium. Australian Journal of Public Administration 64(2): 42–7. DOI: 10.1111/j.1467-8500.2005.00438.x.

Brown, A.J., and Paul Stephen Latimer (2008). Symbols or substance? Priorities for the reform of Australian public interest disclosure legislation. Griffith Law Review 17(1): 223–51.

Cameron, Sarah and Ian McAllister (2019) Trends in Australian political opinion: results from the Australian Election Study 1987–2019. Canberra: ANU College of Arts and Social Sciences. https://australianelectionstudy.org/wp-content/uploads/Trends-in-Australian-Political-Opinion-1987-2019.pdf.

Centre for Public Integrity (2021). Independent funding tribunal required to stop political cuts to accountability institutions. Media release, 27 May. https://publicintegrity.org.au/independent-funding-tribunal-required-to-stop-political-cuts-to-accountability-institutions.

Douglas, Roger and Margaret Hyland (2015). Administrative law (3rd edition.). Chatswood, NSW: LexisNexis Butterworths.

Franklin, Mark N., Stuart N. Soroka and Christopher Wlezien (2014). Elections. In Mark Bovens, Robert Goodin and Thomas Schillemans, eds. The Oxford handbook of public accountability. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Grattan, Michelle (2020). More ‘sports rort’ questions for Morrison after Bridget McKenzie speaks out. The Conversation, 6 March. https://theconversation.com/more-sports-rort-questions-for-morrison-after-bridget-mckenzie-speaks-out-133160.

Grube, Dennis, and Cosmo Howard (2016). Is the Westminster system broken beyond repair? Governance: An International Journal of Policy, Administration and Institutions 29(4): 467–81. DOI: 10.1111/gove.12230.

Head, Michael (2005). Administrative law: context and critique. Sydney: Federation Press.

Hegarty, Nicole (2022). Federal government’s climate bill clears final hurdle, becomes law. ABC News, 8 September. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2022-09-08/fed-gov-climate-bill-clears-final-hurdle-becomes-law/101416538.

Henninger, Maureen (2018). Reforms to counter a culture of secrecy: open government in Australia. Government Information Quarterly 35(3): 398–407. DOI: 10.1016/j.giq.2018.03.003.

House of Representatives Standing Committee on Procedure (2021). A window on the House: practices and procedures relating to Question Time: Report. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia. https://www.aph.gov.au/Parliamentary_Business/Committees/House/Procedure/Questiontime/Report.

Hunter, Fergus (2019). Home Affairs boss won’t seek more resources for FOI section. Sydney Morning Herald, 15 November. https://www.smh.com.au/politics/federal/home-affairs-boss-won-t-seek-more-resources-for-foi-section-20191115-p53b1b.html.

Jaensch, Dean (1996). The Australian politics guide. Melbourne: Macmillan Education Australia.

Karp, Paul (2021). Labor, One Nation and Rex Patrick unite to decry Coalition’s refusal to release national cabinet documents. The Guardian, 30 November. https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2021/dec/01/labor-one-nation-and-rex-patrick-unite-to-decry-coalitions-refusal-to-release-national-cabinet-documents.

Knaus, Christopher (2021). Federal anti-corruption body won’t be operational before next election, budget papers reveal. The Guardian, 12 May. https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2021/may/12/australia-federal-budget-2021-zero-funding-for-commonwealth-integrity-commission-anti-corruption-body-coalition.

McIntyre, Joe (2022). Novak Djokovic’s path to legal vindication was long and convoluted. It may also be fleeting. The Conversation, 10 January. https://theconversation.com/novak-djokovics-path-to-legal-vindication-was-long-and-convoluted-it-may-also-be-fleeting-174603.

Mintrom, Michael, Deirdre O’Neill and Ruby O’Connor (2021). Royal Commissions and policy influence. Australian Journal of Public Administration 80(1): 80–96. DOI: 10.1111/1467-8500.12441.

Moon, Danielle (2018). Freedom of information: user pays (and still faces delays). Alternative Law Journal 43(3): 192–96. DOI: 10.1177/1037969X18787297.

Mulgan, Richard G. (2003). Holding power to account: accountability in modern democracies. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Murphy, Katharine (2020). Morrison shrugs off censure of aged care minister Richard Colbeck over Covid conduct. The Guardian, 3 September. https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2020/sep/03/morrison-shrugs-off-censure-of-aged-care-minister-richard-colbeck-over-covid-conduct.

Near, Janet and Marcia Miceli (1985). Organizational dissidence: the case of whistle-blowing. Journal of Business Ethics 4 (Feb): 1–16.

New South Wales Ombudsman (2021). 2020 hindsight: the first 12 months of the COVID-19 Pandemic: special report. https://www.ombo.nsw.gov.au/Find-a-publication/publications/reports-to-parliament/other-special-reports/2020-hindsight-the-first-12-months-of-the-covid-19-pandemic.

Ng, Yee-Fui (2021). Sussan Ley and the Gold Coast apartment: murky rules mean age of entitlement isn’t over for MPs. The Conversation, 9 January. https://theconversation.com/sussan-ley-and-the-gold-coast-apartment-murky-rules-mean-age-of-entitlement-isnt-over-for-mps-70993.

—— (2022). Will the National Anti-Corruption Commission actually stamp out corruption in government? The Conversation, 5 October. https://theconversation.com/will-the-national-anti-corruption-commission-actually-stamp-out-corruption-in-government-191759.

O’Donovan, Darren. (2020). The ‘problem’ is not ‘fixed’. Why we need a royal commission into robodebt. The Conversation, 23 June. https://theconversation.com/the-problem-is-not-fixed-why-we-need-a-royal-commission-into-robodebt-141273.

Olsen, Johan P. (2014). Accountability and Ambiguity. In Mark Bovens, Robert Goodin, and Thomas Schillemans, eds. The Oxford Handbook of Public Accountability. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Prasser, Scott (2006). Royal Commissions in Australia: When should governments appoint them? Australian Journal of Public Administration 65(3): 28-47.

Ray, Andrew, Bridie Adams and Dan Thampapillai (2022). Access to algorithms post-Robodebt: do Freedom of Information laws extend to automated systems? Alternative Law Journal 47(1): 10–15. DOI: 10.1177/1037969X211029434.

Remeikis, Amy (2021). A sludge of grandstanding: does Question Time finally need some answers? The Guardian, 23 May. https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2021/may/23/a-sludge-of-grandstanding-does-question-time-finally-need-some-answers.

Romzek, Barbara. S., & Melvin J. Dubnick (1987). Accountability in the Public Sector: Lessons from the Challenger Tragedy. Public Administration Review, 47(3): 227–238. DOI: 10.2307/975901.

Sampford, Charles, Rodney Smith and A.J. Brown (2005). From Greek temple to bird’s nest: towards a theory of coherence and mutual accountability for national integrity systems. Australian Journal of Public Administration 64(2): 96–108.

Savage, Shelly, and Rodney Tiffen (2007). Politicians, journalists and ‘spin’: tangled relationships and shifting alliances. In Sally Young, ed. Government communication in Australia. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Schultz, Julianne (1998). Reviving the Fourth Estate: democracy, accountability and the media. Melbourne: Cambridge University Press.

Senate Environment and Communications References Committee (2021). Australia Post: Final Report. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia.

Thompson, Elaine (2001). The Constitution and the Australian system of limited government, responsible government and representative democracy: revisiting the Washminster mutation. UNSW Law Journal 24(3): 657–69.

Transparency International (2021). Corruption Perceptions Index: Australia. https://www.transparency.org/en/cpi/2021/index/aus.

Uhr, John (2005). Terms of trust. Sydney: UNSW Press.

Visentin, Lisa and Mike Foley (2022). ‘No integrity’: Pocock attacks Labor’s climate bill ahead of Senate debate. Sydney Morning Herald, 5 September. https://www.smh.com.au/politics/federal/no-integrity-pocock-attacks-labor-s-climate-bill-ahead-of-senate-debate-20220904-p5bf90.html.

Weller, Patrick (1999). Disentangling concepts of ministerial responsibility. Australian Journal of Public Administration 58(1): 62–4. DOI: 10.1111/1467-8500.00072.

Weller, Patrick (2007). Cabinet government in Australia, 1901-2006: practice, principles, performance. Sydney: UNSW Press.

About the author

Diana Perche is Senior Lecturer in Social Research and Policy at the University of New South Wales, Sydney. Diana’s research focuses on the participation of First Nations people in Australian politics and policy making, and on how Australian governments use evidence and ideology to design public policy affecting or targeting Indigenous people.

- Perche, Diana (2024). Accountability. In Nicholas Barry, Alan Fenna, Zareh Ghazarian, Yvonne Haigh and Diana Perche, eds. Australian politics and policy: 2024. Sydney: Sydney University Press. DOI: 10.30722/sup.9781743329542. ↵

- Franklin, Soroka and Wlezien 2014. ↵

- Grube and Howard 2016. ↵

- Uhr 2005, 1. ↵

- Mulgan 2003, 15–17. ↵

- Mulgan 2003, 20. ↵

- Mulgan 2003, 9. ↵

- Bovens 2010. ↵

- Romzek and Dubnick 1987, 228–9. ↵

- Table adapted from Romzek and Dubmick 1987, 229. ↵

- Olsen 2014. ↵

- Cameron and McAllister 2019, 98 ↵

- Cameron and McAllister 2019, 99 ↵

- Transparency International 2021. ↵

- Remeikis 2021; House of Representatives Standing Committee on Procedure 2021. ↵

- Weller 1999. ↵

- Ng 2021. ↵

- Grattan 2020. ↵

- Weller 2007, 212. ↵

- Prime Minister Anthony Albanese’s Code of Conduct for Ministers can be found on the website of the Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet, https://www.pmc.gov.au/resource-centre/government/code-conduct-ministers ↵

- For more information on parliamentary practice in the lower house, see the collection of House of Representatives Infosheets published on the Australian Parliament House website, including Infosheet 14 – Making decisions – debate and division, https://www.aph.gov.au/About_Parliament/House_of_Representatives/Powers_practice_and_procedure/00_-_Infosheets ↵

- Thompson 2001; Jaensch 1996, 195–9. ↵

- For more information on Senate practice, see the collection of Senate Briefs published on the Australian Parliament House website, including Senate Brief 4 – Senate Committees, https://www.aph.gov.au/About_Parliament/Senate/Powers_practice_n_procedures/Senate_Briefs ↵

- Visentin and Foley 2022; Hegarty 2022. ↵

- Murphy 2020. ↵

- Senate Environment and Communications References Committee 2021. ↵

- Australian National Audit Office. Administration of Commuter Car Park Projects within the Urban Congestion Fund, Auditor-General Report No.47 2020–21, 21 June 2021. https://www.anao.gov.au/work/performance-audit/administration-commuter-car-park-projects-within-the-urban-congestion-fund ↵

- ANAO 2020, Foreword; see also Knaus 2021. ↵

- Centre for Public Integrity 2021. ↵

- For more information on the judiciary as a branch of government, see the chapter ‘Courts’ by Hooper in this volume. ↵

- Church of Scientology v Woodward (1982) 154 CLR 25 at 70. ↵

- Douglas and Hyland 2015, 7. ↵

- McIntyre 2022. ↵

- R v Toohey: ex parte Northern Land Council (1981). ↵

- Head 2005, 11. ↵

- Administrative Decisions (Judicial Review) Act 1977 at section 13. ↵

- Administrative Appeals Tribunal Act 1975. ↵

- Ombudsman Act 1976. ↵

- New South Wales Ombudsman 2021, chapter 3. ↵

- Schultz 1998, 95. ↵

- Savage and Tiffen 2007, 79; see also the chapter on ‘Media and democracy’ by Griffiths in this volume. ↵

- Freedom of Information Act 1982, section 3; see also Henninger 2018. ↵

- Moon 2018. ↵

- Ray, Adams and Thampapillai 2022. ↵

- Hunter 2019. ↵

- Karp 2021. ↵

- Near and Miceli 1985, 2; see also Brown and Latimer 2008. ↵

- Mulgan 2003, 108. ↵

- Brown 2019. ↵

- Brown and Head 2005, 42. ↵

- Sampford, Smith and Brown 2005. ↵

- For a full list of Commonwealth integrity agencies, see Australian Public Service Commission 2021. ↵

- Brown and Head 2005. ↵

- Prasser 2006; Mintrom, O’Neill and O’Connor 2021. ↵

- ABC News 2021. ↵

- Ng 2022; Brown 2022. ↵

- O’Donovan 2020. ↵