47 Evidence and policy making

Mitzi Bolton

Key terms/names

causation, citizen science, co-design, cognitive biases, consequence, correlation, cost–benefit analysis, evidence-based, evidence-informed, likelihood, multi-criteria analysis, opportunity cost, peer review, qualitative, quantitative, review, risk, systematic, transaction cost

Introduction

We like to think that policy decisions are based on the best possible evidence, and that the choices we make for our society are well founded.[1] However, what constitutes the best possible information is highly debatable. This chapter explores what constitutes evidence, why we consider it to be so, what gets in the way and how to overcome barriers to evidence informing public policy design.

Since becoming a dominant focus of practitioner and academic discussions after being popularised by the UK Cabinet Office in 1999,[2] considerable time and effort has been spent exploring the merits or otherwise of an evidence-based approach.[3] Here the focus is less on why we should use evidence and more on what we need to think about as we collect and use it.

Yarnold et al. note that ‘Increasingly, policymakers and regulators are in unchartered waters where they must act promptly but with caution, weighing potential benefits and harms’.[4] This weighing up of potential benefits and harms cannot occur without evidence. Evidence is the critical underpinning of all policy making and implementation.

While this might seem obvious, evidence collection and analysis are often an afterthought. Too little time and foresight are assigned to adequately gathering insights that shed light on how effective past efforts have been and why, what the current issues are, and what form of contemporary policy design is needed. Consequently, policy makers can unfairly dismiss evidence for being inaccessible, too time-consuming to procure or otherwise incompatible with policy making. Evidence-based policy makers do their best to counter such critiques not only via the use of data but by establishing and maintaining mechanisms to ensure ongoing data collection.

What constitutes evidence and how it is used in policy design can be highly subjective. To navigate this subjectivity, policy makers need to recognise that the things they hold as unquestioned truths may not be true for other actors in the policy space. At times this may feel deeply uncomfortable. However, it is important to remember the policy designer’s role as both public servant and steward is to be responsive to community aspirations, while also advancing and acting as a custodian of institutional knowledge.

Conceptions of evidence

What counts as evidence? While this might seem a simple question, the array of potential responses that can arise and their manifestations within public policy development show it is highly contested.

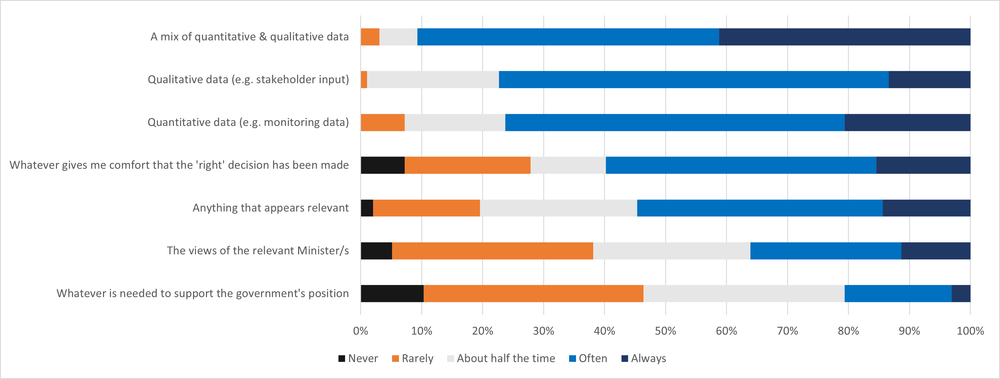

Some would say evidence is what can be measured scientifically. Others may say evidence is what can be observed, perhaps thinking of a witness to a crime. Some would say people’s feelings or emotions count as evidence: for example, community sentiment on a local issue. Still others might be less discriminating and say it is anything that helps make the point or support a position (Figure 1).

The Productivity Commission reflected this breadth in defining five types of evidence:

- quantitative evidence: what can be numerically measured

- qualitative evidence: what can be learnt from observation or discussion

- descriptive evidence: opinion and anecdotes

- existing evidence: what is already known, reviews of reviews

- experimental evidence: indicative findings from research and policy trials.[5]

Whatever form the ‘what’ of evidence takes, why it is thought about in that way is a critical consideration in public policy design. Hence, policy makers need not only to use evidence but also to seek to appreciate the different kinds of evidence available, and find policy positions reflecting or at least acknowledging these varied interpretations.

Many different understandings and rationales of what constitutes evidence will be encountered when working in or adjacent to the public sector, that is, either as or with policy makers. These understandings of what is ‘true’ often manifest into firmly held beliefs and can get in the way of negotiated paths forward.

As noted, evidence is subjective.[6] Classically trained scientists, for example, may struggle to accept descriptive or emotive evidence. In contrast, social scientists may find quantitative evidence to be too removed from experiential inputs. Evidence drawn from outside Western traditions is another area where there can be difficulty in reaching agreement. However, Indigenous knowledges are gaining increasing recognition after having long been disregarded with detrimental impacts.[7]

This subjectivity is somewhat tackled by the precautionary principle which argues that a lack of scientific evidence should not result in inaction where there is the risk of permanent or irreversible damage but there are well-documented debates about where the burden of proof in demonstrating the need for precaution sits.[8] For example, societal demands for particular outcomes may support or contradict precaution – evident in the changing appetites of the community to COVID-19 protections being required. Similarly, inaction on climate change has demonstrated how vested interests and/or the need for long-term planning and spending to enable widespread system change can inhibit application of the precautionary principle despite public support for it.[9]

Because of this contestation, policy makers must seek to understand, negotiate and incorporate different evidence forms. Failing to do so can lead to further contestability in defining the problem to be solved. Without an agreed problem definition, much policy design work will struggle to reach its true potential and likely have a short lifespan before being overturned.

While people’s personal preferences, limited training and shifts in what is considered best practice can lead to limited recognition of the value of standardised processes,[10] such processes can support policy makers to transparently document how and why policy decisions were made. These processes help identify which agencies in which tiers of government have authority to draft and implement policy, the limits of their scope, and rules around what constitutes evidence. While processes differ between jurisdictions and policy outputs (that is, government position pieces versus regulation versus legislation), they typically include similar components such as problem definition, consideration of solutions, quantification of the costs and benefits of (in)action, and identification of implementation and evaluation plans.[11]

All of these process steps are, or ought to be, underpinned by evidence. Processes which draw on evidence enable policy choices to transparently emerge from what is known, and what matters to those affected. This transparency, in turn, can provide a platform for future incremental adjustments rather than necessitating expensive and exhausting wholesale change.

Common evidence traps

Evidence interpretation

Even with standardised processes, the approach to identifying evidence requirements and its subsequent integration into policy considerations will vary by policy designer and organisation. Thus, it is essential to interrogate and document what the evidence represents: what is it telling us? What are we looking for? What have we overlooked? Why?

Again, differing people will see things differently and being able to step into the shoes of others is a critical skill for policymakers. Sometimes these perspectives can lead to situations where ‘solutions search for problems’.[12] That is, rather than searching for a solution based on what the evidence suggests, evidence is collected or interpreted to create a problem which fits a pre-identified solution. Another common trap is mistaking correlation for causation: mistaking unrelated things as genuinely having cause-and-effect relationships. Such situations may be the result of goodwill (for example, having seen a solution work elsewhere), but do not lend themselves to robust, evidence-based resolution of public problems.

Stepping into the shoes of others

During the COVID-19 pandemic many governments made policy decisions that significantly affected people’s daily lives, such as the hours they could leave their homes, when they could or could not work, the people they could or could not see, and things they had to wear, such as masks.[13] Some in the community saw this as significant overreach, as a genuine risk of authoritarianism and erosion of libertarian values.[14] Others saw this as evidence of the government acting in the community’s best interests, of seeking to prevent health and economic systems collapse. Neither group was easily persuaded to join or accept the other’s views.

For some, the positions taken were ideologically driven. For others, the decision was based on personal experience. Perhaps if there were high case numbers in your local area, you were more willing to accept the impositions. On the other hand, if restrictions prevented you from being with your loved one during their final days, you might have been more inclined to reject them.

While a strong society looks beyond individual interests, our circumstances give us different perspectives and viewpoints on what is right, and this influences considerations of what is most important and how evidence should be considered.

Correlation ≠ causation

In 2012, the Commonwealth government introduced a policy to expand the VET FEE-HELP scheme (a vocational education and training program). Almost 200,000 students took up the scheme, resulting in $2.9 billion in loans and training provider payments. On face value, this enrolment and loan data could easily be misinterpreted as a sign that the scheme expansion was successful in enhancing growth in the vocational education and training sector.

However, inadequate considerations of risks, consequences and incentives resulted in up to a quarter of students being unaware they were enrolled in a training program or had taken on an associated financial loan. Consequently, it was estimated $2.2 billion in loans were unlikely to be recovered or repaid and the scheme was ultimately shutdown.

In reviewing the program and the responsibilities of the three agencies directly or indirectly responsible for it, the Australian National Audit Office found it demonstrated a need to emphasise all program objectives and outcomes and develop key performance indicators (KPIs) accordingly.[15] Doing so would have created multiple data points to consider, making it easier to identify where correlation rather than causation was leading to impressions of success, and resolve issues within the program sooner.

Timely evidence

Few immediate responses to crises can be informed by a holistic embrace of the evidence. Instead, crises typically arise because of complex or unrecognised public needs. That is, we knew there was a problem but, despite our awareness of it, couldn’t prevent it from becoming a crisis (for example, increased natural disasters because of climate change), or widespread acknowledgement of the problem didn’t occur until it was on our doorstep (for example, the COVID-19 pandemic).

Dealing with such issues quickly, as is likely to be the political and immediate social desire, often cannot occur in a fully evidence-informed way. More commonly, a review several years later will evaluate and refine those initial responses. This reflects the reality that policy decisions must often be made in a context of partial information, uncertainty, and rapidly shifting understandings of the problems to be addressed.

Evidence-driven practitioners can support both immediate and refining responses to crises by enabling evidence collection practices in anticipation of such inflection points.

Evidence ignored

An altogether different issue arises when others within the policy design sphere, be they colleagues, line managers or ministers, seemingly refute or ignore the evidence. It may be that fixed mindsets or organisational cultures do not support an evidence-based or evidence-informed approach. Yet, evidence rarely provides a yes/no directive. Evidence is a tool that requires judgement to decipher when aiming to mitigate a harm or enhance public value. Evidence alone will not create change; it can only point in the right direction.

Seeking to uncover why there is resistance to evidence or evidence-based options can be one of the most important skills of a policy maker. Where institutional hierarchies prevent discussion with senior officials such as ministers, secretaries, or agency CEOs, examining relevant media, Hansard, organisational strategies, and ministerial statements of expectations can also act as a check. It may be that of all the factors a decision maker must consider, evidence as conceived by some is not the foremost priority.[16]

Moreover, it can be important to consider what the resistance to a proposal is driven by; perhaps it is not a refusal of the evidence after all. Campbell and Kay argue ‘solution aversion’ may be the cause. They note: ‘people may deny problems not because of the inherent seriousness of the problems themselves but because of the ideological or tangible threat posed by the associated policy solutions’.[17] For example, presenting a solution at odds with the elected government’s agenda is unlikely to be well-received, no matter the evidence. In situations where the evidence implies such a solution is needed, policy makers need to articulate the rationale for it within the context and framing of the government’s stated goals.

This leads to an area of debate within academic and practitioner circles – the place of the policy maker and evidence-based policy within a democratic society. It is the members of parliament who are elected and accountable to the public, and thus it is ministers and the parliament who have the final call on whether a policy proceeds. However, the ways in which policy makers can present evidence to senior decision makers ahead of such decisions is highly debated.[18] Some argue the role of policy makers is solely to implement the will of the government of the day;[19] others say that a skilled public service provides contextual and evidence-based insights to not only support the government of the day but also act as an enduring caretaker for the institutions of government themselves.[20]

While subject matter experts may be best placed to provide evidence of one persuasion – for example, chief health officers providing advice on the mitigations needed to minimise the impacts of the pandemic – ministerial judgements need to take the multiple lenses of evidence into account and may ultimately go against such advice. At times such judgements can be seen as political. However, as ultimate decision maker, it is the Minister’s prerogative to take or disregard the insights shared by policymakers and experts.

To balance expectations on the public sector more effectively, policy makers can seek to understand ministerial and senior officials’ goals and style, and rely on evidence, not emotion, to convey policy ideas. Such an approach can assist in building trust in the public sector’s judgement and support for the evidence-based reforms it proposes. This can be particularly important in providing the public sector with greater autonomy in making the many decisions delegated to it by the parliament, and hence in speeding up less contentious public decisions. This building of trust also helps to create a culture in which public servants are able to be ‘frank and fearless’ – where the public sector provides robust advice without hesitation in the knowledge that ultimately ministerial judgements may lead to a different outcome.[21]

Valuing (multiple kinds of) evidence

Policy makers are often supported by tools that help to demonstrate and weigh trade-offs between options. As far as possible, these tools involve consideration of quantitative data, which a third party could validate if desired. Sometimes, however, numerical data is absent, incomplete or, as discussed, not reflective of broader sentiment and the types of risk a policy seeks to address. Sometimes, community and business sentiment and anecdotes are equally compelling. As Brian Head puts it, ‘There is not one evidence-base but several bases’.[22] It is incumbent on policy makers to seek out, be open to and reasonably analyse and integrate these bases to develop a fuller picture of the policy domain they seek to influence.

Commonly cost–benefit[23] or multi-criteria[24] analyses will be conducted to underpin a case for change. Both have their proponents and critics, but increasingly there is recognition that it needn’t be a choice between one or the other. Including multiple lines of evidence, particularly for contentious policy reforms, can provide greater confidence in the decisions made and reduce political risk.

Perhaps the strongest reasoning for multiple lines of evidence in policy development is that, even where there is clear agreement on the evidence, what works best now will inevitably be different to what works best in a decade. Technical advances, and shifting societal and political understandings and risk appetites will alter what is considered acceptable, as perceptions on what counts as evidence and how that evidence can or should be applied evolve.[25] This means that what is (un)acceptable today may not be tomorrow.

Risk

Underpinning all public decisions is risk. Choices around which risks we are willing to accept, and which need to be mitigated, are informed by evidence on the likelihood and consequence of such risks arising. Here too, there may be debates about what best constitutes evidence of risk, leading to further debate on how likely and consequential a risk may actually be.

Haines describes three kinds of risk commonly addressed by government policy:

- actuarial (harms to individuals)

- socio-cultural (threats to societal stability and wellbeing)

- political (risk to the legitimacy and power held by government or the incumbent governing party).[26]

For actuarial risks, there are often scientific or numerical values widely accepted as ‘truths’ to be designed around. For example, we know exposure to contaminants at certain levels can harm human health, so laws are put in place to prevent such exposures.[27] For socio-cultural and political risks, quantitative data can be less singularly compelling as values and ideology play a bigger role in framing what counts. Further, the three kinds of risk are interconnected, so addressing one type of risk in isolation rarely resolves a public issue.

In addition to the actuarial, social, and political risks that lead to evidence collection are risks created by the act of evidence collection itself. For example, policy makers must be careful not to set expectations they cannot meet. Without establishing the purpose of evidence collection, asking stakeholders for their views on an issue can imply something will be done to resolve the issue, or that stakeholder views will determine the outcome. Similarly, evidence collection can expose previously unknown issues and, on occasion, the significance of these can supersede the original focus of policy design, scuttling plans and timelines.

Policy makers also need to be wary of gathering too much information and landing themselves in a sea of data they can’t quite make sense of. This risk of ‘analysis paralysis’ emphasises the importance of collecting data with purpose and intent. Focused collection also helps contain political risk: if too little data is collected, government will be accused of ignoring key issues or pandering to particular interest groups; however, if more information is collected than can be analysed or acted on, government risks a situation arising where it held but did not act on knowledge – as occurred in the lead up to the 9/11 terrorist attacks.[28]

Developing an evidence base

Getting started

Once a need for reform or a new policy agenda is identified, thoughts turn to where evidence and inputs for analyses can be found. In the best-case scenario, past policy developers have recorded the rationale for decisions, and subsequent implementation processes included mechanisms for data collection as part of ongoing and future evaluations. Much time and effort can be saved where there is clear documentation of what happened before, why, and the outcomes of those decisions.

More commonly, policy makers tasked with developing reforms or novel policy positions are told to get in touch with department X or person Y, ‘who might know something’, before finding themselves as the baton in a seemingly endless relay of, ‘try person A, B, C … Z’. Yet organisational staff are often untapped fonts of knowledge: they work in the space every day, know where the pain points are, and where the inhouse data is. It is not unheard of for frontline teams to keep spreadsheets of the things they know need fixing, with field-based evidence of those needs, in anticipation of one day being asked for input and evidence to support policy reforms. So, asking how they do things, what works and what doesn’t, can unearth a great deal. Consequently, as a public policy practitioner, cultivating an ecosystem of people you can speak to and exchange ideas with over time can prove invaluable.

Failing such intel, reading speeches captured in Hansard, legislative impact assessments and regulatory impact statements, parliamentary committee reports, auditor-general and ombudsman reviews, organisational websites, newspaper articles, community blogs, and project awards, can be incredibly instructive. Especially, when seeking to build an evidence base on what has happened before and why. Increasingly such materials are freely available online in contemporary or historical databases.[29]

The lesson here is twofold:

- Don’t assume you know the answer or be afraid to ask around for what is already known.

- Always document and hand on your own policy-evidencing processes as though it is you who will need to make sense of them in ten years. What has happened is often far easier to decipher than why it did.

Stakeholder input

Forming this base understanding of prior decisions and the outcomes arising from them enables policy makers to embrace current stakeholder inputs and perspectives with an open mind. That is not to say designers should develop a fixed view, nor that building a body of evidence cannot occur in parallel to stakeholder engagement. However, for a policy designer who has limited exposure to the topic they’ve been tasked with, taking a step back to understand the landscape can be invaluable in helping to identify who needs to be engaged, how, and in making the best use of stakeholders’ time.

It is not unusual for stakeholders to be tired of promises of reform in areas that matter to them, and to be frustrated that they need to do the legwork by repeating stories that could easily have been uncovered had policy makers simply gone looking. Hence, policy makers who show some attempt at understanding issues are often met with less hostility, and a greater willingness to assist.[30]

Notwithstanding the above, stakeholders’ stated and revealed preferences – what they say and what they do – are widely recognised to differ.[31] Hence, asking external stakeholders what is needed can often only provide part of the policy problem and solution picture. This further highlights the need for policy makers to incorporate many evidence types and inputs to their work.

Similarly, while current fashions of co-design and co-production can help ensure a more collaborative dialogue between policy makers and stakeholders, designers still need to understand the space they are working in. One of the risks of co-design is the potential for other perspectives to be overlooked or disregarded entirely. That is, evidence from those outside the co-design process may not be collected or considered. To avoid this, policy makers need to learn who else might have an interest or view and find ways to include their voices.[32]

Another meaningful way to engage with stakeholders in evidence collection is through citizen science, where laypeople collect and provide data to inform policy development and condition monitoring. While such efforts may be dismissed as disingenuous or unreliable by some, publicly sourced information increasingly informs decision making by public bodies.[33] Such tools make future policy and management decisions far more likely to be evidence-based. Citizen scientists are now also a vital data source for technical government reports, such as State of the Environment reviews, with retired experts and interested amateurs alike generating robust datasets.[34]

Citizen science

SnapSendSolve (https://www.snapsendsolve.com/), a mobile phone app, enables community members to document and alert councils to minor issues in the area (such as trip hazards, burst pipes, graffiti, uncollected rubbish and so on). This tool makes it easier for community members to be part of neighbourhood improvements, and provides local governments with the ability to identify and prioritise issues requiring fixing without increasing their staffing costs, while also documenting how frequently particular problems arise.

Evidence of costs

While evidence is critical for robustly defining a problem and identifying potential solutions, it is also imperative in establishing the costs of reform, monetary or otherwise. There is a need to consider not only the more obvious transactional costs and benefits of a policy design, but also the opportunity costs: that is, what alternative outcomes are prevented by acting or not acting.

Similarly, policy makers need to look beyond obvious factors to properly establish if the cumulative burden created by a proposal is proportionate to the risk or public good being addressed. Perhaps the costs of a proposed policy are reasonable in isolation but not when considered amidst the legislative burdens faced.

Consider, for example, a neighbourhood takeaway food outlet. It is subject to federal, state and local laws on planning, food safety, liquor licensing, parking and deliveries associated with the business, signage and outdoor tables – to name but a few interactions. Adding another requirement – even one intended to help reduce risks to the trader, their staff and customers – may be the final straw that pushes a trader to close.

Tools such as time-limited subsidies – where the cost to receive a policy benefit is subsidised for a period – can help address concerns about transactional and opportunity costs and unreasonable burdens. These enable those who will benefit from a policy to experience its value before being required to pay for it. The subsidy period also enables collection of evidence on the impact of the policy, providing for smoother transitions to paying modes, and supporting future decisions and education campaigns regarding the policy.

Another consideration is the authority policy makers have to collect information. Providing data to government can be a time-intensive activity that takes away from individuals’ and businesses’ capacity to add value to society. Further, collecting and housing data is not without cost to government: storing data carries a financial and political obligation to use and act upon that data. Policy makers must articulate what data is needed, why, and how it will be used. Where such questions can’t be answered, it may suggest the public value of data collection has not been established and lead to concerns of scope creep or refusal to approve or provide shared data.

The costs of public policy to end-users are not the only ones to be contemplated. The practicalities, trade-offs, and benefits for implementing agencies also need to be considered. For example, evidence may suggest a need for occupational health and safety (OHS) laws concerning working at heights to be applied to residential solar panels installations. However, the dispersed nature and relatively short timeframes of solar panel installations make enforcing such a policy prohibitively difficult: how would an OHS regulator know when and where panel installers are on any given day? Policy makers must actively look for evidence of impracticalities and seek to address them by understanding the broader landscape within which their policy objectives sit, and potential reform partners.

Understanding the broader landscape

Solar Victoria runs a solar panel rebate scheme and has leveraged the incentive of participating in the scheme to support WorkSafe (Victoria’s OHS regulator) to address the implementation issue of knowing when and where to inspect the safety of those installing solar panels. By requiring those who participate in their subsidy scheme to provide and grant permission to share data on when and where installations will occur before they occur, Solar Victoria is positioned to collect and pass on information to WorkSafe, which can then conduct more targeted and packaged site inspections. This has also benefitted Solar Victoria, which has observed improved industry practices and standards. Examples such as this demonstrate how evidence is used not only to form policy but also to ensure that policy is implementable, and create synergistic outcomes across public programs.

‘Expert’ input

With such an array of considerations, policy makers must retain a critical mindset, particularly regarding the quality of the evidence and the biases those analysing or presenting it may have (including their own!). Within the research community, there are hierarchies of evidence that can be used to interpret evidence and inform policy design.[35]

The best-quality evidence is arguably that which has undergone independent and blind peer review, as is the case in scholarly articles published in academic journals. But, due to the rigour underpinning academic research and writing, peer-reviewed works can be slow to enter the public domain. This lag between evidence collection, analysis, and availability means peer-reviewed evidence can struggle to align with policy timelines. Additionally, while there is an encouraging shift toward open access publication and many authors upload copies of their work online, many peer-reviewed articles remain behind paywalls, making it difficult for policy makers without institutional subscriptions to gain access to key information.

In the absence of peer-reviewed works, preprints can be helpful. These share current findings in anticipation of rigorous review and, thus, are typically written and presented in a manner consistent with peer-reviewed articles. Preprints have been used for decades within fields such as physics, astronomy and mathematics, and their utility in enhancing the speed of research sharing and innovation is leading to their increased use in other fields (many early COVID-19 studies were shared as preprints). However, as the peer-review process is an integral part of evidence validation, evidence drawn from preprints should be flagged as such and noted when compared with other evidence sources.

Systematic reviews or meta-analyses can also be particularly useful for policy makers. These draw together peer-reviewed papers to provide an overarching analysis of what is known, highlighting gaps and consensus in past evidence collection efforts.[36] Systematic reviews can provide a more accessible way to quickly appraise the literature for relevant material.

As they are inherently looking backward and are also peer-reviewed, systematic reviews don’t necessarily address concerns around delays between evidence creation and publication. To overcome this, there has been a recent trend within policy circles toward scoping or rapid reviews. These ‘lite’ reviews are able to be built more quickly but are not as comprehensive as systematic reviews.[37]

Another way to stay across the forefront of research can be to approach researchers directly. Often experts in fields will be identifiable from their submissions to government consultations or their participation in key conferences and forums. Failing this, a Google Scholar search on the topic of interest will yield a list of peer-reviewed articles typically sorted by how many times others have referred to them. From this, one can tell whom other researchers consider experts in the field and reach out to them.

Getting ahead of the game

Policy design needn’t be a case of perpetually looking backwards to determine how to move forward. Adapting or instituting mechanisms to collect data purposefully and without significant cost to others is possible.

Technology

Increasingly technology can support this focus. Telecommunications and Apple and Google movement data were used to inform (and assess the effectiveness of) COVID-19 policy decisions.[38] In more regular times, such tools enhance transportation outcomes, such as indicating in real-time which public transport services will connect, thereby encouraging their uptake, or by mapping travel routes that discourage traffic from residential streets, thus avoiding the need for costly traffic-calming infrastructure.[39]

Similarly, the burgeoning use of satellite data and ground-sensing cameras to monitor remote locations supports natural resource management and provides pathways for broader policy objectives to be achieved.[40] For example, mapping forested areas not only allows monitoring of the health and extent of the vegetation, it also holds the potential to identify bushfire risks and lightning strikes,[41] and provides a pathway to auditable carbon credits.[42]

The ability of advanced data-science tools to collect and analyse large datasets and identify anomalies provides other benefits, including speeding up more straightforward tasks. For example, digitisation can be used to detect fraudulent welfare or tax claims,[43] speeding up standard policy implementation tasks to provide data in a more timely manner and freeing staff to focus on more complex work.

Similarly, pattern recognition capabilities can inform policy analysis work, for example, by enhancing understandings of service interactions and where to intervene so as to improve the functioning and impact of public systems.[44] At an individual officer level, technology can also increase efficiency and awareness of engagement efforts through coordination, automation and analysis of stakeholder inputs.[45] Such tools enable policy makers to ‘hear’ from more people and more objectively analyse the concerns and ideas raised.

Of course, outsourcing evidence collection and analysis requires robust quality-assurance mechanisms, as evidenced by the Robodebt scandal, a decision to automate identification of alleged benefit fraud with minimal oversight, which had considerable impact on the individuals and families identified by the automation.[46] Moreover, the biases we seek to overcome using technology can also be inadvertently built into that technology.[47] Auditing a portion of the collected or analysed data to check it matches expected or required outcomes is a great way to provide confidence in the evidence, analysis of a situation and ultimately the policy itself.

Eventually, the use of technology may improve public decisions by supporting policy makers to overcome their cognitive biases – unconscious errors made by human brains to deal with complexity.[48] Technology capable of analysis and prediction may support more optimised decision making and will likely find a common place in future policy makers’ toolkits. To achieve this, barriers such as cost and public sector access to data will need to be overcome in ways which preserve private sector and community trust in government decision making.

Process innovation

While technology is likely to have an increasing role in policy design, low-tech options such as reflecting on how things can be done differently also improve evidence collection. Reviewing organisational evidence collection systems to confirm they are as efficient and effective as possible, or if simple tweaks might better support policy design now and into the future can be a relatively cheap and effective approach. Such tweaks needn’t alter the standard of evidence required but may simply enhance the processes needed to collect and consider it.

Enhancing evidence processes

The COVID-19 approval process in Australia provides an example of how tweaks enabled real-time improvements without undermining the integrity of the evidence collection system.

More traditional processes involve the proponent developing a single application containing all relevant data needed for a regulatory decision. However, given the urgency for vaccines created by the pandemic, Australia’s Therapeutic Goods Administration shifted to a rolling submission approach to reviewing COVID-19 vaccines.[49] This approach meant pharmaceutical companies provided the information needed for vaccine approvals as soon as they could collect it, even if some aspects were initially incomplete. Regulatory officials similarly provided rolling feedback, enabling issues to be identified and resolved as quickly as possible without reducing overall rigour or the standard of evidence required.[50]

Conclusion

Public decisions are arguably strongest when evidence underpins policy design, implementation, and review. Yet, with so many different conceptions of evidence, each underpinned by different schools of thought and life experience, agreeing on what counts as evidence can be a significant hurdle for policy makers.

While different forms and traditions of evidence are increasingly being recognised, paving the way for a broader array of voices to be heard, reconciling these different forms can be difficult. The available evidence may lead to tensions as those involved hold fast or are made to question why they see things as they do. Nevertheless, policy makers who want to develop enduring policy that meets the needs of most, if not all, must do their best to find that balance.

This means gathering as much but not more evidence than needed, in all its available forms, with whatever time and resources policy makers have. It means keeping an open mind and acknowledging the constraints and limitations faced along the way and the uncertainties they’ve created. It means having a plan C as well as a plan B. And, ultimately, it means questioning and being willing to non-defensively accept the insights new information may bring – even if that challenges the worldviews of policy makers themselves.

Policy design isn’t easy. But it is important, and can only be faithfully undertaken when we genuinely observe and question what the evidence is telling us.

References

ADR (Administrative Data Research) UK (2021). Data first: harnessing the potential of linked administrative data for the justice system. https://www.adruk.org/our-work/browse-all-projects/data-first-harnessing-the-potential-of-linked-administrative-data-for-the-justice-system-169/

Althaus, Catherine (2020). Different paradigms of evidence and knowledge: recognising, honouring, and celebrating Indigenous ways of knowing and being. Australian Journal of Public Administration 79(2): 187–207. DOI: 10.1111/1467-8500.12400

Althaus, Catherine, Peter Bridgman, and Glyn Davis (2013). The Australian policy handbook, 5th edn. Sydney: Allen & Unwin.

Apple Inc. (2022). Mobility trends reports. https://covid19.apple.com/mobility

Australian National Audit Office (2016). Administration of the VET FEE-HELP Scheme. https://www.anao.gov.au/work/performance-audit/administration-vet-fee-help-scheme.

Australian Taxation Office (2021). How we use data and analytics. Australian Taxation Office. https://www.ato.gov.au/About-ATO/Commitments-and-reporting/Information-and-privacy/How-we-use-data-and-analytics

Australian Citizen Science Association (2022). Australian Citizen Science Association. https://citizenscience.org.au

Australian Human Rights Commission. (2020). Using artificial intelligence to make decisions: addressing the problem of algorithmic bias. Technical paper. Sydney: Australian Human Rights Commission.

Ballard, Ed. (2022). Tech startups race to rate carbon offsets. Wall Street Journal, 25 January. https://www.wsj.com/articles/tech-startups-race-to-rate-carbon-offsets-11643115605

Beshears, John, James J. Choi, David Laibson and Brigitte C. Madrian. (2008). How are preferences revealed? Journal of Public Economics 92(8): 1787–94. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpubeco.2008.04.010

Bolton, Mitzi (2020). Factors influencing public sector decisions and the achievement of sustainable development in the State of Victoria, Australia. PhD thesis. Australian National University, Canberra.

Cairney, Paul (2016). The politics of evidence-based policy making. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

—— and Kathryn Oliver (2016). If scientists want to influence policymaking, they need to understand it. Guardian, 27 April. https://www.theguardian.com/science/political-science/2016/apr/27/if-scientists-want-to-influence-policymaking-they-need-to-understand-it

—— and Kathryn Oliver (2020). How should academics engage in policymaking to achieve impact? Political Studies Review 18(2): 228–44. DOI: 10.1177/1478929918807714

Campbell, T.H., and A.C. Kay (2014). Solution aversion: on the relation between ideology and motivated disbelief. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 107(5): 809–24. DOI: 10.1037/a0037963

Clarke, Edward J.R., Anna Klas and Emily Dyos (2021). The role of ideological attitudes in responses to COVID-19 threat and government restrictions in Australia. Personality and Individual Differences 175: 110734. DOI: 10.1016/j.paid.2021.110734

Cochrane (2022). About Cochrane reviews. Cochrane Library. https://www.cochranelibrary.com/about/about-cochrane-reviews

Commissioner for Environmental Sustainability (2020). Framework for the Victorian State of the Environment 2023 Report: science for sustainable development. Melbourne.

Dartington Service Design Lab (2022). An integrated approach to evidence for those working to improve outcomes for children & young people. https://www.dartington.org.uk/s/Integrated-Approach-Dartington-Service-Design-Labs-Strategy-Paper.pdf

Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet (2019). Our public service, our future. Independent review of the Australian public service. Canberra: Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet, Commonwealth of Australia.

French, Richard D. (2018). Lessons from the evidence on evidence-based policy. Canadian Public Administration 61 (3): 425–42. DOI: 10.1111/capa.12295

Google (2022). Report wrong directions in Google maps. Google maps help. https://bit.ly/4baUH9D

—— (n.d.). COVID-19 community mobility reports. https://www.google.com/covid19/mobility

Grubb, Ben (2020). Mobile phone location data used to track Australians’ movements during coronavirus crisis. Sydney Morning Herald, 5 April. https://www.smh.com.au/technology/mobile-phone-location-data-used-to-track-australians-movements-during-coronavirus-crisis-20200404-p54h09.html

Haines, Fiona (2017). Regulation and Risk. In Peter Drahos, ed. Regulation Theory. Canberra: ANU Press.

Han, Emeline, Melisa Mei Jin Tan, Eva Turk, Devi Sridhar, Gabriel M. Leung, Kenji Shibuya, Nima Asgari, Juhwan Oh, Alberto L. García-Basteiro, Johanna Hanefeld, Alex R. Cook, Li Yang Hsu, Yik Ying Teo, David Heymann, Helen Clark, Martin McKee and Helena Legido-Quigley (2020). Lessons learnt from easing COVID-19 restrictions: an analysis of countries and regions in Asia Pacific and Europe. Lancet 396 (10261): 1525–34. DOI: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32007-9

Harris, Anne (2022) statement made in Regulatory Reform Challenges session, at Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet and IPAA ACT Regulatory Reform: Supporting business investment and growth conference. https://bit.ly/3SdHgx7

Head, Brian W. (2008). Three lenses of evidence-based policy. Australian Journal of Public Administration 67(1): 1–11. DOI: 10.1111/j.1467-8500.2007.00564.x

—— (2013). Evidence-based policymaking – speaking truth to power? Australian Journal of Public Administration 72: 397–403. DOI: 10.1111/1467-8500.12037

—— and Subho Banerjee. (2019). Policy expertise and use of evidence in a populist era. Australian Journal of Political Science 55(1): 110–21. DOI: 10.1080/10361146.2019.1686117

Hecker, Susanne, Muki Haklay, Anne Bowser, Zen Makuch, Johannes Vogel and Aletta Bonn (2018). Innovation in open science, society and policy – setting the agenda for citizen science. In Susanne Hecker, Muki Haklay, Anne Bowser, Zen Makuch, Johannes Vogel and Aletta Bonn, eds. Citizen Science, 1–24. London: UCL Press.

Higgins, J.P.T., J. Thomas, J. Chandler, M. Cumpston, T. Li, M.J. Page and V.A. Welch, eds (2022). Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions version 6.3. bit.ly/3OOAXxN

Hudson, Marc (2019). ‘A form of madness’: Australian climate and energy policies 2009–2018. Environmental Politics 28(3): 583–9. DOI: 10.1080/09644016.2019.1573522

Institute for Marine and Antarctic Studies (2022). Redmap. https://www.redmap.org.au

Kingdon, John W. (1995). Agendas, alternatives, and public policies. 2nd edn. New York: HarperCollins.

MacDermott, K. (2008). Whatever happened to ‘frank and fearless?: the impact of the new public service management on the Australian public service. Canberra: ANU EPress.

Miller, Lynn, Mitzi Bolton, Julie Boulton, Michael Mintrom, Ann Nicholson, Chris Rüdiger, Robert Skinner, Rob Raven and Geoff Webb (2020). AI for monitoring the Sustainable Development Goals and supporting and promoting action and policy development. Paper presented at the IEEE/ITU International Conference on artificial intelligence for good (AI4G), Geneva, Switzerland, 21–25 September.

Miller, Lynn, Liujun Zhu, Marta Yebra, Christoph Rüdiger and Geoffrey I. Webb (2022). Multi-modal temporal CNNs for live fuel moisture content estimation. Environmental Modelling and Software 156: 105467. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsoft.2022.105467

National Commission on Terrorist Attacks Upon the United States (2004). The 9/11 Commission Report. https://www.govinfo.gov/features/911-commission-report

Newman, Joshua (2022). Politics, public administration, and evidence-based policy.’ In Andreas Ladner and Fritz Sager, eds. The Elgar Handbook on the Politics of Public Administration. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar.

——, Adrian Cherney and Brian W. Head.(2016). Policy capacity and evidence-based policy in the public service. Public Management Review 19(2): 157–74. DOI: 10.1080/14719037.2016.1148191

Office for National Statistics UK (2021). Splink: MoJ’s open source library for probabilistic record linkage at scale. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/joined-up-data-in-government-the-future-of-data-linking-methods/splink-mojs-open-source-library-for-probabilistic-record-linkage-at-scale

Productivity Commission (2018). What works review protocol. Melbourne: Productivity Commission – Commonwealth of Australia.

—— (2009). Strengthening evidence-based policy in the Australian federation. https://www.pc.gov.au/research/supporting/strengthening-evidence

Purtill, James (2021). Australia’s first satellite that can help detect bushfires within one minute of ignition set for launch. ABC News, 14 March. https://www.abc.net.au/news/science/2021-03-14/bushfires-detecting-them-from-space-fireball-satellite-launch/13203470

Ruggeri, Kai, S. Linden, Claire Wang, Francesca Papa, Zeina Afif, Johann Riesch and James Green (2020). Standards for evidence in policy decision-making. Nature Research Social and Behavioural Sciences 399005. https://socialsciences.nature.com/posts/standards-for-evidence-in-policy-decision-making

Royal Commission into the Robodebt Scheme (2022). https://robodebt.royalcommission.gov.au

Sandman, P.M. (2012). Responding to community outrage: strategies for effective risk communication. http://psandman.com/media/RespondingtoCommunityOutrage.pdf

Simon, Herbert A. (1997). Models of bounded rationality: empirically grounded economic reason. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Taylor, Lenore (2015). Sacking of departmental secretary to have a ‘chilling effect’ on public service. Guardian, 15 March. http://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2015/mar/15/sacking-of-departmental-secretary-to-have-a-chilling-effect-on-public-service

The Clean Air and Urban Landscapes Hub (2016). Three-category approach. https://nespurban.edu.au/3-category-workbook/

Therapeutic Goods Administration (2021). Comirnaty. Department of Health and Aged Care. https://www.tga.gov.au/apm-summary/comirnaty

Tversky, Amos, and Daniel Kahneman (1982). Judgment under uncertainty: heuristics and biases.In Amos Tversky, Daniel Kahneman and Paul Slovic, eds. Judgment under uncertainty: heuristics and biases, 3–20. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

UK Cabinet Office (1999a). Modernising government. White Paper. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/modernising-parliament-reforming-the-house-of-lords

—— (1999b). Professional policy making for the twenty first century. Strategic Policy Making Team, Cabinet Office. https://dera.ioe.ac.uk/6320/

—— (2014). What works? Evidence for decision makers. What Works Network, ed. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/what-works-evidence-for-decision-makers

United Nations (2021). ‘Tipping point’ for climate action: time’s running out to avoid catastrophic heating. UN news. https://news.un.org/en/story/2021/09/1099992

Vardon, Michael, Peter Burnett and Stephen Dovers (2016). The accounting push and the policy pull: balancing environment and economic decisions. Ecological Economics 124: 145–52. DOI: 10.1016/j.ecolecon.2016.01.021

Victorian Government (2021). Victorian guide to regulation. 10 February. https://www.vic.gov.au/how-to-prepare-regulatory-impact-assessments – the-seven-key-questions

Yarnold, Jennifer, Ray Maher, Karen Hussey and Stephen Dovers (2022). Uncertainty: risk, technology and the future. In P.G. Harris, ed. Routledge handbook of global environmental politics. DOI: 10.4324/9781003008873-23

About the author

Dr Mitzi Bolton is a Research Fellow at the Monash Sustainable Development Institute, and the Better Governance and Policy Initiative of the Monash Faculty of Arts. Her research employs systems thinking to identify and test ways to support public servants to improve public outcomes.

Mitzi’s research is driven by the 12 years’ experience she gained across the Victorian and Australian public sectors. Covering both technical and administrative functions, she has held an array of leadership and policy development roles within the Victorian Environment Protection Authority, the Department of Premier and Cabinet (Vic) and the Productivity Commission.

Mitzi holds a Bachelor of Science with Honours from The University of Melbourne, a Master of Commercial Laws from Monash University, and a PhD from the Australian National University’s Crawford School of Public Policy – on factors influencing public sector decisions and the achievement of sustainable development.

- Bolton, Mitzi (2024). Evidence and policy making. In Nicholas Barry, Alan Fenna, Zareh Ghazarian, Yvonne Haigh and Diana Perche, eds. Australian politics and policy: 2024. Sydney: Sydney University Press. DOI: 10.30722/sup.9781743329542. ↵

- UK Cabinet Office 1999a, b. ↵

- Althaus, Bridgman and Davis 2013, see especially 70–6; Cairney and Oliver 2016, 2020; Head 2008, 2013; Head and Banerjee 2019; Newman, Cherney and Head 2016; Newman 2022; Productivity Commission 2009. ↵

- Yarnold et al. 2022, 253. ↵

- Productivity Commission 2009, vol. 2, chapter 1. ↵

- Newman 2022. ↵

- Althaus 2020; The Clean Air and Urban Landscapes Hub 2016. ↵

- Yarnold et al. 2022. ↵

- Hudson 2019; United Nations 2021. ↵

- Vardon, Burnett and Dovers 2016. ↵

- For example, consider the Seven key questions in the Victorian guide to regulation, Victorian Government 2021; Althaus, Bridgman and Davis 2013. ↵

- Kingdon 1995, 86. ↵

- Han et al. 2020. ↵

- Clarke, Klas and Dyos 2021. ↵

- See Australian National Audit Office 2016, especially 7–14. ↵

- Bolton 2020. ↵

- Campbell and Kay 2014, 810. ↵

- Cairney 2016; French 2018; Newman 2022. ↵

- Taylor 2015. ↵

- Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet 2019, 40. ↵

- MacDermott 2008; Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet 2019, 90, 293. ↵

- Head 2008. ↵

- Cost–benefit analyses (CBAs) assign monetary values to options for comparison. Cost–benefit analyses have a long history of use, but can fail to reflect the complexity of human endeavour. ↵

- Multi-criteria analysis can be helpful where quantitative evidence is missing or irrelevant to the risk at hand or there is a diversity of views on what should occur. As the name suggests, Multi-criteria analyses draw together and consider varying forms of evidence to suggest a way forward. Multi-criteria analyses can be criticised for their subjectivity and limited replicability. ↵

- Dartington Service Design Lab 2022; Head 2008. ↵

- Haines 2017. ↵

- National Environment Protection (Assessment of Site Contamination) Measure 1999, as amended 2013. ↵

- National Commission on Terrorist Attacks Upon the United States 2004. ↵

- For example, Trove – a digital collection of Australian artefacts – can be beneficial in locating older materials. ↵

- Sandman 2012. ↵

- Beshears et al. 2008. ↵

- Dartington Service Design Lab 2022. ↵

- Hecker et al. 2018. ↵

- Commissioner for Environmental Sustainability 2020; Institute for Marine and Antarctic Studies 2022; Australian Citizen Science Association 2022. ↵

- Ruggeri et al. 2020. ↵

- For example, Higgins et al. 2022; Cochrane 2022. ↵

- UK Cabinet Office 2014; Productivity Commission 2018. ↵

- Grubb 2020; Apple Inc. 2022; Google n.d https://www.google.com/covid19/mobility/ ↵

- For example, Google will change map directions based on safety advice from authorities flagged through their ‘Report wrong directions’ support page – Google 2022. ↵

- Miller et al. 2020. ↵

- Purtill 2021; Miller et al. 2022. ↵

- Ballard 2022. ↵

- Australian Taxation Office 2021. ↵

- ADR (Administrative Data Research) UK 2021; Office for National Statistics UK 2021. ↵

- For example, the state of Victoria uses an online platform Engage.vic to co-ordinate and increase awareness of consultation activities. ↵

- Royal Commission into the Robodebt Scheme 2022. ↵

- Australian Human Rights Commission 2020. ↵

- Tversky and Kahneman 1982; Simon 1997. ↵

- Therapeutic Goods Administration 2021. ↵

- Statement made by Anne Harris, Manager Director, Pfizer, in Regulatory Reform Challenges session, at Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet and IPAA ACT, 2022 Regulatory Reform: Supporting business investment and growth conference. ↵