24 Multicultural Australia

Juliet Pietsch

Key terms/names

assimilationism, ethnicity, integration, multiculturalism, non-English-speaking backgrounds (NESB), Office of Multicultural Affairs (OMA), public opinion, race

The rise and fall of multiculturalism[1] and public support for multiculturalism in Australia has historically been influenced by social issues, such as public concerns about globalisation, national identity, immigration, social cohesion and population growth. In contrast to other settler countries, multiculturalism was originally developed to dismantle the White Australia policy and provide the legislative and policy foundations for supporting migrants from non-English-speaking backgrounds (NESB). In Australia, multiculturalism has focused primarily on the needs of migrants and their right to express their cultural identities. Attempts to include Indigenous Australians in multicultural policy have been met with caution due to the concern of conflating issues regarding Indigenous Australians (especially with regards to land rights, constitutional recognition and reconciliation) with distinctly migrant experiences.[2]

Multiculturalism is underpinned by a vast body of philosophical literature on modern liberalism and cultural diversity that examines the concept of a ‘politics of difference’.[3] Kymlicka, for instance, explores the importance of collective rights to self-determination. These rights can be held by individuals or groups, such as minority nationals or Indigenous peoples.[4] Kymlicka argues that cultural group rights are needed, on the one hand, to protect a cultural community from forced segregation and, on the other, to provide enough flexibility to protect other communities from forced integration (i.e. Indigenous peoples).[5]

Countries have approached multiculturalism differently due to their unique historical, legal and cultural circumstances. For instance, in Canada multiculturalism was introduced to resolve tensions between French- and English-speaking Canadians. There was a much stronger emphasis on the institutionalisation of multiculturalism in Canada than in Australia, which was strengthened in 1982 with the inclusion of protections for Canada’s multicultural heritage in the Charter of Rights and Freedoms. This was followed by the Canadian Multiculturalism Act 1988 which aimed to address the under-representation of minority groups in parliament. In contrast, Australia has never adopted a legal framework for multiculturalism. Instead, it has focused on improving social and economic outcomes for migrants from NESB. Before the introduction of multiculturalism in Australia, migrants from NESB struggled with low levels of English literacy and were often the victims of racism and discrimination due to the enduring impact of the White Australia policy.

This chapter focuses on the development of multiculturalism in Australia, as distinct from other countries around the world. The first section of the chapter traces the development of multicultural Australia in three distinct phases: 1) integration of non-British postwar European migrants; 2) social justice and equality; and 3) citizenship and civics. The second section of the chapter examines public attitudes towards multiculturalism over time, drawing on findings from the Australian Election Studies, and reflects on the meaning of multicultural Australia in the 21st century.

The development of multicultural Australia

After the Great Depression and the Second World War, Australia moved towards an ethnically plural program, concomitant with a significant decline in arrivals in Australia of migrants with British origins. By the 1940s, it was clear that immigration from Britain was not going to be sufficient to achieve economic growth in Australia. Therefore, Australia’s immigration resources were diverted from Britain to the refugee issues in western and southern Europe. To assist with overpopulation and fears of political instability in Europe, Australia was persuaded by the International Refugee Organisation to accept large numbers of people displaced by the war. After the Second World War, the decision to initiate a program of mass migration was announced in the Commonwealth parliament by the first minister for immigration, Arthur Calwell.

Australia introduced the assisted European migration program, which began in 1947. The Australian government was initially hesitant to admit Greek and Italian refugees because they were seen as culturally different and politically suspect due to the influence of communism in their home countries.[6] However, due to the demand for labour, the program eventually accepted 170,000 refugees from countries including Malta (1948), Italy and the Netherlands (1951), Germany, Austria and Greece (1952), Spain (1958), Turkey (1967) and former Yugoslavia (1970).[7] European immigration peaked in the 1960s, with a total of 875,000 assisted passages.[8] Overall, the European immigration program helped to increase the size of the workforce and contributed to postwar economic expansion.[9] Postwar migrants formed the backbone of the manufacturing sector and the Snowy Mountains Hydro-Electric Scheme. In fact, it could be argued that the Snowy Mountains Scheme, which attracted over 100,000 migrants from Europe under assisted migration schemes, was the beginning of multicultural Australia.

In this period, the ideology behind the European immigration program was ‘assimilationism’. Non-British migrants were encouraged to naturalise and assimilate.[10] In 1945, Arthur Calwell, the minister for immigration in 1945–49, proposed that ‘Australian nationality’ be equated with Australian citizenship to facilitate immigration and deportation, the issue of passports and the representation of Australians abroad.[11] Calwell proposed that to qualify as an Australian national one should be:

- a person born in Australia who has not acquired another nationality

- a British subject not born in Australia who was not a prohibited immigrant at his time of entry and has resided in Australia for five years

- a person naturalised in Australia who has residence of five years

- the wife of an Australian national who is herself a British subject resident in Australia, or

- a child born outside Australia whose father, at the time of birth, was an Australian national.[12]

Following the 1947 Commonwealth Conference on Nationality and Citizenship, the Commonwealth nations agreed on a system of nationality and citizenship. In 1949, Australian citizenship came into being after the enactment of the Nationality and Citizenship Act 1948 (Cth). Citizenship was seen as a crucial component of nation building.[13] However, Australian citizenship was still associated with being a British subject.

The conception of citizenship based on a sense of national belonging led to different levels of discrimination against non-British migrants. For example, non-British subjects could only obtain citizenship after five years, whereas British subjects only had to wait one year to obtain citizenship.[14] In terms of eligibility for citizenship, there was also discrimination between Asian migrants and European migrants. For instance, by 1958, Asian migrants were required to live in Australia for 15 years or more before becoming eligible for naturalisation under the Migration Act 1958 (Cth). By contrast, European migrants only had to wait five years for naturalisation.[15]

At the 1952 citizenship convention, the minister for immigration, Harold Holt, referred to the importance of restrictions in Australia’s immigration policy. He stated that restrictions were not based on racial superiority, but rather on differences between cultures that make successful assimilation difficult.[16] Although Holt was mainly referring to migrants from Asian backgrounds, this discrimination was also directed towards southern European migrants, who were often provided little or no support for their resettlement. For example, in 1952, the Department of Immigration’s social workers reported severe distress among non-British migrants, where shelters for the homeless were unable to cope and thousands were left sleeping in parks.[17]

During the 1960s, Australia entered a recession with large-scale unemployment among the thousands of migrants recently arrived in the country.[18] Welfare departments provided low-level services but were not properly equipped to cope with the large numbers of people from NESB. For example, during this time, professional interpreters were minimal within government services.[19] The problems associated with settlement for all migrants from NESB and the need for them to assimilate and conform to a culturally different environment created a build-up of pressure on the government to change its migrant settlement and welfare policy. By the end of the 1960s, it was evident that no single government department could meet all the settlement needs of migrants. The government suggested that migrant settlement services should be dispersed into other government departments and agencies.[20]

During the late 1960s, many European migrants experienced poor working conditions and poor health associated with unhealthy working environments and unemployment.[21] James Jupp’s Arrivals and departures (1966) provided significant insight into anti-assimilationist complaints and migrant welfare problems. Jupp criticised the lack of government housing, the lack of pensions for elderly migrants, the high number of migrants in low-skilled employment, the lack of recognition of overseas qualifications, poor protection of migrant workers by Australian unions and the lack of English-language courses and available interpreters.[22]

Other researchers also highlighted the disadvantaged situation of migrants in Australia and contributed to the public debate on the problems of assimilation.[23] For example, Jerzy Zubrzycki argued for a commitment to cultural diversity through promoting the teaching of foreign languages.[24] Jean Martin also highlighted the importance of ethnic pluralism at numerous conferences. Martin argued that migrant groups existed in varying degrees of isolation because there were no mechanisms to help them settle into Australian life. Martin, an advocate of ethnic pluralism, blamed the assimilation policy and the ‘de-valuation’ and ‘non-recognition’ of migrant institutions and cultures for the problems that migrants had to endure.[25] Between 1969 and 1971, integrationist migrant welfare programs were initiated, which aided migrant English-language competence, social mobility, social integration and the improvement of migrant welfare services.[26]

In 1973, the Labor government, under the leadership of Prime Minister Gough Whitlam, promoted a reconceptualisation of Australian national identity in terms of multiculturalism. The term ‘multiculturalism’ was borrowed from Canada but applied differently in the Australian context. The Labor minister for immigration, Al Grassby, identified that nearly a million migrants had not taken up Australian citizenship because of their experiences of racism and discrimination. Grassby suggested encouraging the retention of social and cultural differences among non-British Australians. In response, the Australian Citizenship Bill 1973 (Cth) was introduced in 1973, reflecting a new national identity that was anti-racist and challenged assimilationist values.[27] The focus of citizenship shifted from culture and British inheritance to the principle of territoriality – that is, residence on the territory of the Australian state.[28]

In 1974, the government also introduced a Bill to combat racial discrimination and ratify the United Nations Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination, to which Australia had been a signatory since 1966 but had not ratified. The Bill was passed by both houses of the Commonwealth parliament on 4 June 1975 and became the Racial Discrimination Act 1975 (Cth). The legislation made it unlawful to discriminate against a person because of their nationality, race, colour or ethnicity. The passing of the Racial Discrimination Act 1975 formally ended the White Australia policy. However, that policy had such a significant impact on the public imagination and sense of national community and identity that its effects lingered for decades afterwards.

The Whitlam government attempted to fill the void left by the old nationalism, and redefined the concept of Australia’s ‘national community’.[29] The new national identity was to be more inclusive, embracing liberal humanist values, progressive ideals and overall social reform.[30] The success of the Whitlam government at the 1974 election represented popular endorsement of the changes made by Gough Whitlam. For example, Murray Goot found that ‘the polls of 1974 and 1975 were the first of their kind to produce clear majorities in favour of the current rate of immigration’.[31] However, problems with the Whitlam reforms began to emerge when the Whitlam government was placed under pressure with the build-up of refugees in camps in South-East Asia as a result of the war in Vietnam, which displaced up to 800,000 people.

With increasing numbers of Asian migrants in the late 1970s, the government was under international pressure to move ahead of the general population of Australia in endorsing a new ethnically inclusive national identity. Migrant services and programs: the report of the review of post-arrival programs and services to migrants, known as the Galbally report, was introduced in 1978 as a key driver in formulating government policies affecting migrants. At the heart of the report was the need to provide encouragement and financial assistance for migrants so that they could maintain their cultural identity.[32] The Galbally report recommended:

- improvements in the Adult Migrant Education Program, which was initiated in 1947 to teach survival English to refugees

- free telephone interpreter services for migrants from NESB and emergency services

- the establishment of Migrant Resource Centres

- the introduction of a Special Broadcasting Service (SBS).[33]

The Fraser government strongly supported the recommendations of the report, initiating expanded migrant settlement services and seeking to promote cultural pluralism as a source of strength to Australia’s national identity rather than a threat. The Galbally report suggested shifting migrant services from the general area of social welfare to ‘ethnic specific’ services.[34] For example, Galbally proposed that many on-arrival services be provided through voluntary organisations, rather than through public agencies.[35] He also recommended withdrawing government funding from the Good Neighbour Councils, which were originally set up in 1949 to cater to the needs of non-British European refugees.[36] Overall, between 1976 and 1983, the Fraser government reduced spending by shifting funding from government agencies to voluntary organisations within the community. Therefore, cultural diversity was encouraged, but only if political and economic structures were left intact.[37]

When the Labor government was elected in 1983, it set about reforming some of the Liberal policies of multiculturalism. The Review of Migrant and Multicultural Programs and Services (ROMAMPAS) was released in 1986. It proposed a strategy of providing basic resources and support for cultural expression, stressing the importance of equality. The report suggested four principles for developing government policies:

- All members of the Australian community should have an equitable opportunity to participate in the economic, social, cultural and political life of the nation.

- All members of the Australian community should have equitable access to an equitable share of the resources that governments manage on behalf of the community.

- All members of the Australian community should have the opportunity to participate in and influence the design and operation of government policies, programs and services.

- All members of the Australian community should have the right, within the law, to enjoy their own culture, to practise their own religion and to use their own language, and should respect the right of others to their own culture, religion and language.

The focus of the report was ensuring equal opportunity and outcomes for all Australians. The report also recommended the establishment of an Office of Multicultural Affairs (OMA), which was set up in 1987 and assumed responsibility for the Commonwealth Access and Equity Strategy.[38] As part of this responsibility, the OMA prepared the National Agenda for Multicultural Australia, which focused on the issues of access to public services and equity in the allocation of public resources. The OMA identified three new directions for multicultural policy:

- cultural maintenance and respect for cultural difference

- promotion of social justice

- recognition of the economic significance of an ethnically and culturally diverse community.[39]

The principles of multiculturalism were broadly accepted by the Hawke and Keating Labor governments throughout the 1980s and early 1990s.[40] However, with the rise in Asian immigration, there were rumblings that the government was moving too far ahead of public opinion. For example, Geoffrey Blainey argued that the immigration policy in the early 1980s was insensitive to the views of the majority of Australians. In All for Australia, Blainey criticised Australia’s immigration policy and the slogan ‘Australia is part of Asia’. He argued that Australia was importing unemployment but not announcing what it was doing.[41] Furthermore, he criticised the nature of multiculturalism as an identity for Australia:

Multiculturalism is an appropriate policy for those residents who hold two sets of national loyalties and two passports. For the millions of Australians who have one loyalty this policy is a national insult.[42]

Blainey’s criticisms were later echoed in the mid-1990s. For example, in 1996, leader of the One Nation Party (ONP), Pauline Hanson, expressed the following concerns about Asian immigration and multiculturalism in her maiden speech in federal parliament:

Immigration and multiculturalism are issues that this government is trying to address, but for far too long ordinary Australians have been kept out of any debate by the major parties. I and most Australians want our immigration policy radically reviewed and that of multiculturalism abolished. I believe we are in danger of being swamped by Asians.[43]

The recognition of ethnic difference in multiculturalism was interpreted by the ONP as a form of disrespect to Anglo-Australian identity.[44] In fact, it is possible that ONP populism caused the most damage to multiculturalism. In 1996, the newly elected Howard Liberal–National (Coalition) government made cuts in the areas of immigration and multiculturalism. The term ‘multiculturalism’ as a defining component of national identity was also losing support.

In the late 1990s, questions were raised about whether an ethnically diverse nation can also be a unified nation. According to Ruth Fincher, over the years there have been two opinion groups. First, there are those who support the idea that ‘an ethnically diverse population, its growth fuelled by sustained and non-discriminatory immigration, benefits the “nation” by improving its economic resources, its social breadth, its international linkages, and its citizenship’.[45] Second, there are those who suggest that ethnic diversity weakens the character of national identity. According to Fincher, ‘theirs is a view of essential Australianness that sees a national character as having been formed amongst Anglo-Australians from the time of English settlement’.[46] Since the 9/11 terrorist attacks in the USA, the latter view has become more prominent in the Australian media because of fears of Australia becoming a fragmented society.

The rise of transnationalism tends to encourage states to reassert their authority in shaping national identity and national citizenship.[47] The frequency of terrorist attacks has also led to governments reaffirming national identity and establishing new citizenship obligations. As a result, Eleonore Kofman argues that more than ever ‘the state is asserting its role as protector of national identity and social cohesion’.[48] For instance, the world’s leading democracies began to apply more pressure on migrants to integrate, assimilate and conform to civic values.[49] One of the casualties of the new focus on civic integration was multiculturalism. The new assertiveness of liberal states to impose liberal values, such as democracy and gender equality, coincided with a retreat from multiculturalism in theory and policy.[50]

The shift to civic integration was partly due to the pressure to maintain a secure environment and also to obtain public consent for large-scale influxes of skilled migrants.[51] In Australia, in 2006, there were suggestions in the media that a national consensus supporting high immigration would be at risk unless the Australian public tackled the key issues of common values, social cohesion and multiculturalism.[52] Furthermore, on the fifth anniversary of the 9/11 terrorist attacks, former Prime Minister John Howard and opposition leader Kim Beazley led national debates on immigration, values and terror. Howard said, ‘people in Australia are in no doubt that extreme Islam is responsible for terrorism’ and Kim Beazley called for ‘all new Australians to sign up to Australian values when they applied for their visas’.[53] The debates in the Australian media escalated quickly following the London terrorist attacks in 2005 and the fear of home-grown terrorism. Zubrzycki, one of the original proponents of multicultural policy in Australia, stated in The Weekend Australian that he never imagined that his preference for a culturally diverse policy could welcome hard-line isolationist groups antagonistic to Western values.[54]

The combined issues of immigration, national values and terrorism have raised questions as to how the modern nation state should fulfil its role as protector of national identity and social cohesion.[55] The Australian government response has been to support high levels of migration but at the same time demonstrate to the public that they are tightly monitoring the management of migration and diversity.[56] In terms of managing migration, Australia has selected migrants based on their utility to the economy and on the skills shortage. In terms of managing diversity, migrants with transnational links have been encouraged to integrate and embrace Australian civic values.[57] Political leaders have led debates on the issues of Australian national values and citizenship as a way of rethinking questions of social cohesion and national identity.

At the turn of the century, with nearly 25 per cent of Australians born outside the country, with transnational connections, the Coalition government specifically focused on the notion of citizenship as a basis for a collective national identity. The government proposed more difficult and protracted citizenship tests. In October 2006, Liberal MP Petro Georgiou criticised the government’s discussion paper ‘Australian citizenship: much more than just a ceremony’ in a speech delivered to the Murray Hill Society at the University of Adelaide. Georgiou argued that difficult and protracted citizenship tests were not necessary to promote social cohesion and integration. In particular, Georgiou criticised the proposed English tests, arguing that the take-up of citizenship is lowest among English speakers. For example, migrants from the UK, New Zealand and the USA have traditionally had lower take-up rates of citizenship than migrants from non-English-speaking countries.

With no real break in terrorist incidents in Western countries, and subsequent concerns about racial and ethnic tensions, the civic approach to multiculturalism and social cohesion was largely supported by successive Labor and Liberal governments in the first two decades of the 21st century. Fears about terrorism on home soil in Australia were realised in Sydney in 2014, when Australians witnessed the Lindt cafe siege, which took place in front of a television studio. A lone gunman – Man Haron Monis – with a Muslim background entered the cafe and held hostage up to ten customers and eight employees. After a 16-hour stand-off hostages Tori Johnson and Katrina Dawson were killed, along with the gunman, when police raided the cafe. Since the Lindt cafe siege, there have been several other attacks by individuals with Muslim backgrounds, including in Sydney in 2015, when an Iraqi youth attacked with a knife and shot an accountant who worked for the New South Wales Police in Parramatta, and in Melbourne in 2018, when a Somali migrant stabbed three pedestrians and a police officer, who later died in hospital. These attacks further damaged government support for multiculturalism. They also harmed Muslim communities that in most cases had fled from wars, terrorism and religious violence in their countries of origin, only to be confronted with the reality of politically motivated violence once again.

Public support for multiculturalism

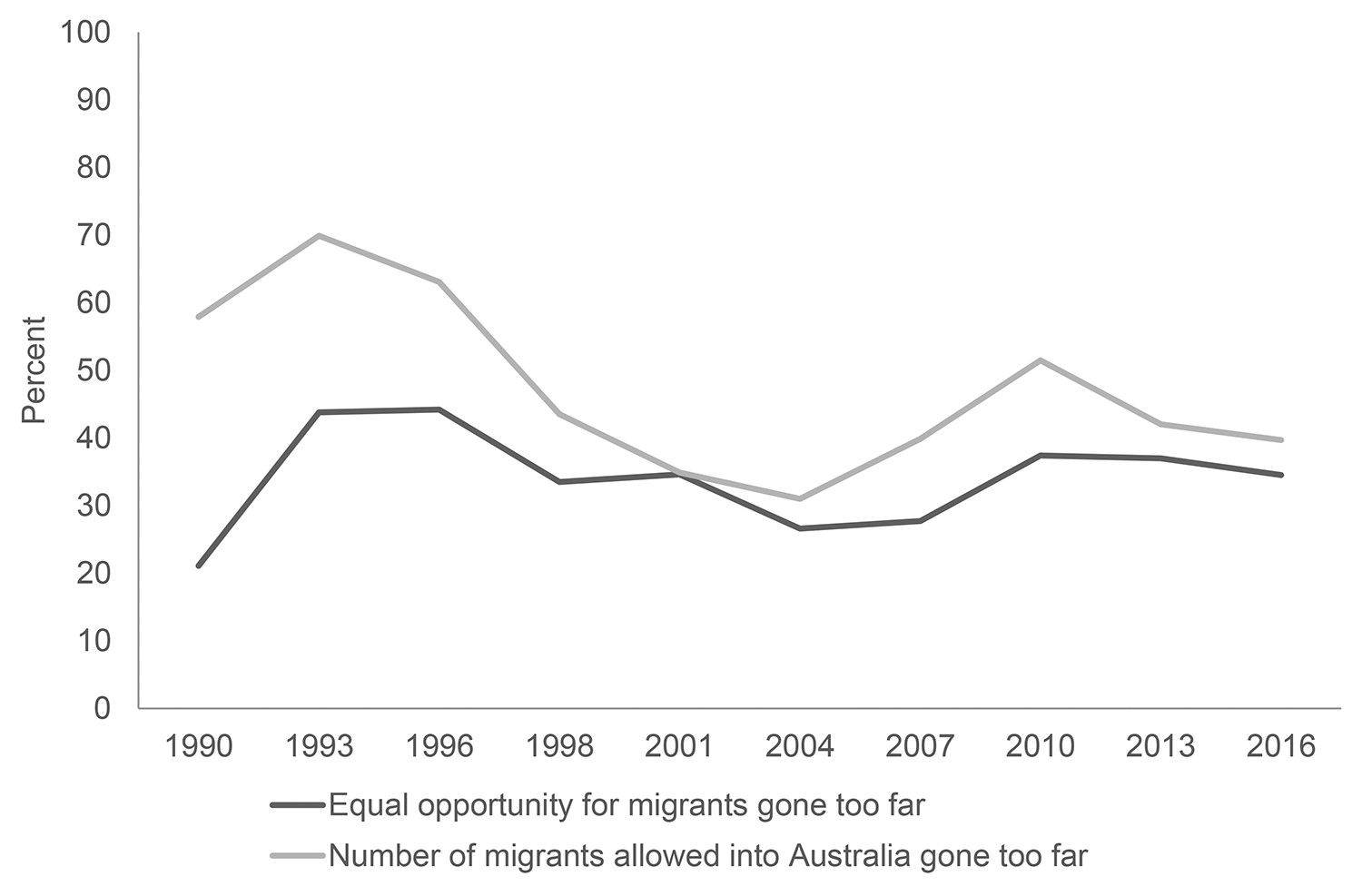

So far, this chapter has looked at the development of multicultural Australia from the perspective of government in response to changing immigration patterns, public fears about national identity, globalisation and national security. However, throughout the changes in government policy, the broader Australian public has maintained consistent views towards multiculturalism. One way to measure public attitudes towards multiculturalism is to ask people whether they feel equal opportunities for migrants have gone too far. As can be seen in the previous section, the original goals of multicultural Australia were to provide equal opportunities for migrants through a range of programs, such as providing English as a second language support for migrants from NESB, as well as a range of migrant welfare, cultural and translation services.

Figure 1 shows the results from the 1990–2016 Australian Election Studies. The Australian Election Study surveys a representative sample of Australians each election year, asking questions on a range of social and political issues. The advantage of the Australian Election Studies is the way in which the surveys track political attitudes and behaviours over time, asking the same questions in each election year. The results in Figure 1 reveal that up to 44 per cent of respondents were not overly supportive of multiculturalism in the early 1990s. Interestingly, the percentage that were concerned about multiculturalism decreased in the years leading up to the 9/11 terrorist attacks and the follow-up concerns about migration, particularly arrivals of asylum-seekers with Muslim backgrounds. Asylum-seeker arrivals became a source of political controversy during the 2001 election campaign. In 2001, the Howard government, in what became known as the ‘Tampa Affair’, claimed that asylum seekers had thrown their children overboard to secure long-term protection in Australia. An Australian Senate Select Committee later found that the children of asylum seekers were not placed at risk and that the government had tried to mislead voters.

The percentage of survey participants that were concerned about multiculturalism increased throughout the first decade of the 21st century from 27 per cent in 2004 to 35 per cent in 2016. This may, in part, be related to increasing media attention on terrorist attacks in other countries. However, the results in Figure 1 also show that attitudes towards levels of migration run parallel to attitudes towards multiculturalism, with an increasing percentage of Australians concerned about the number of migrants allowed into Australia. In 2016, more than 40 per cent of the Australian population felt that the number of migrants allowed into Australia had gone too far, increasing from a low of 27 per cent in 2004.

Australian attitudes towards multiculturalism and immigration are also consistently related to several important background factors, such as age, education and political identification. Table 1 shows that, in more recent election years, younger Australians were less likely to be concerned about equal opportunities for migrants, compared to older Australians. For example, in 2016, only 14 per cent of respondents in the ‘18–24’ age bracket expressed, concern compared with over 40 per cent of respondents in the ‘35–44’ and ‘55 and over’ age brackets. In some elections, younger respondents were more likely to express concern about multiculturalism, compared to older respondents, such as in 1990, 1996, 1998, 2001 and 2010. This shows that younger age groups are not always supportive of multiculturalism, as is often assumed, with younger age groups considered to be more progressive than older age groups.

|

|

1990 |

1993 |

1996 |

1998 |

2001 |

2004 |

2007 |

2010 |

2013 |

2016 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Age |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

18–24 |

34 |

46 |

52 |

35 |

40 |

18 |

19 |

42 |

31 |

14 |

|

25–34 |

28 |

46 |

46 |

34 |

36 |

26 |

24 |

30 |

34 |

30 |

|

35–44 |

21 |

43 |

40 |

33 |

34 |

25 |

28 |

42 |

35 |

40 |

|

45–54 |

15 |

40 |

43 |

36 |

34 |

27 |

32 |

42 |

40 |

33 |

|

55–64 |

15 |

41 |

42 |

29 |

31 |

27 |

28 |

34 |

41 |

40 |

|

65+ |

18 |

46 |

46 |

31 |

33 |

29 |

27 |

35 |

39 |

41 |

|

Education |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

No qualification |

26 |

49 |

50 |

36 |

42 |

28 |

30 |

41 |

43 |

39 |

|

Non-tertiary qualification |

19 |

46 |

46 |

37 |

37 |

33 |

34 |

44 |

46 |

46 |

|

Tertiary qualification |

9 |

24 |

28 |

19 |

16 |

15 |

13 |

23 |

21 |

20 |

|

Vote |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Liberal |

20 |

47 |

50 |

31 |

37 |

33 |

32 |

45 |

45 |

40 |

|

Labor |

21 |

41 |

36 |

30 |

32 |

21 |

25 |

31 |

31 |

32 |

|

National |

30 |

50 |

59 |

41 |

39 |

31 |

43 |

65 |

47 |

47 |

|

Greens |

|

|

39 |

39 |

17 |

9 |

15 |

25 |

12 |

9 |

The question was, ‘Do you think the following change that has been happening in Australia over the years has gone too far, not gone far enough, or is it about right?’ ‘Equal opportunities for migrants’.

Other, more consistent factors that are related to views on multiculturalism are education and political identification. Those with a tertiary qualification are consistently more likely to support multiculturalism, although even among respondents with a university education there has been a steady increase in the number concerned about multiculturalism, from only 9 per cent of respondents in 1990 to 20 per cent in 2016. Nevertheless, those without a university qualification show a much higher level of concern about multiculturalism, with more than 45 per cent of respondents in 2010 and 2013 and 40 per cent in 2016 stating that equal opportunities for migrants had gone too far. The most consistent factor that is related to views about multiculturalism is how respondents vote during the election. Those who vote for Labor and the Greens at each election have been consistently more likely to support multiculturalism, compared to those who vote for the Coalition. This would be expected because since the 1990s the Labor Party has more actively promoted multiculturalism. Federal and state Labor electorates are also more likely to have significant populations of migrants from both low socio-economic and non-English-speaking backgrounds.

Conclusions

Political leaders, by and large, acknowledge that the old form of nationalism in Australia, based on common history, language and tradition, has declining relevance. These leaders have given expression to what a new ‘national community’ should be. In the 1980s, Prime Minister Bob Hawke supported the view of a ‘national community’ in Australia as defined in terms of multiculturalism. This view was presented in the 1989 National Agenda for a Multicultural Australia. Whitlam, Fraser and Hawke all attempted to reconcile diversity with a common British-Australian identity. However, the use of multiculturalism as a symbol of Australian nationalism began to unravel when subsequent governments began to feel uneasy with the concept.[58] Since the rise of the ONP and conservative politics in the late 1990s and terrorism in the 21st century, consecutive governments have refrained from promoting multiculturalism as a unifying symbol of national identity. Instead, the policy of multiculturalism is considered useful for managing cultural diversity and social cohesion.

The findings of the Australian Election Studies discussed in this chapter show that while there are many ebbs and flows in government policies and public debates on multiculturalism and immigration, there is a fairly consistent level of public support for multiculturalism, especially among those with a tertiary qualification and Labor voters. It appears that efforts among government and media elites to undermine the enduring success of multicultural Australia have had very little success, revealing the inclusivity and egalitarianism of the Australian population.

References

Albrechtsen, Janet (2005). Cultural assault on human rights: at what point do the judges say the laws – our values – apply equally to everyone. The Australian, 24 August, 12.

Allbrook, Malcolm, Helen Cattalini and Associates (1989). Community relations in a multicultural Australia. In James Jupp, ed. The challenge of diversity: policy options for a multicultural Australia, 20–32. Canberra: Australian Government Publishing Service.

Ang, Ien, and John Stratton (2001). Multiculturalism in crisis: the new politics of race and national identity in Australia. In Ien Ang, ed. On not speaking Chinese: living between Asia and the West, 95–111. London: Routledge.

Blainey, Geoffrey (1988). Australians must begin to shout loudly. The Weekend Australian, 2–3 July, 22.

—— (1984). All for Australia. North Ryde, NSW: Methuen Haynes.

Brawley, Sean (1995). The white peril: foreign relations and Asian immigration to Australasia and North America 1919–78. Sydney: UNSW Press.

Castles, Stephen, Bill Cope, Mary Kalantzis and Michael Morrissey (1988). Mistaken identity: multiculturalism and the demise of nationalism in Australia. Sydney: Pluto Press.

Curran, James (2002). The ‘thin dividing line’: prime ministers and the problem of Australian nationalism, 1972–1996. Australian Journal of Politics and History 48(4): 469–86. DOI: 10.1111/1467-8497.00271

Davidson, Alastair (1997). From subject to citizen: Australian citizenship in the twentieth century. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Dutton, David (1999). Citizenship in Australia: a guide to Commonwealth records. Canberra: National Archives.

Faulks, Keith (1998). Citizenship in modern Britain. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Favell, Adrian (1998). Philosophies of integration: immigration and the idea of citizenship in France and Britain. Basingstoke, UK: Macmillan Press.

Fincher, Ruth (2001). Immigration research in the politics of an anxious nation. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 19(1): 25–42. DOI: 10.1068/d278t

Galbally, Frank (1978). Migrant services and programs: report of the review of post-arrival programs and services for migrants. Canberra: Australian Government Publishing Service.

Goot, Murray (1988). Immigrants and immigration: evidence and argument from the polls 1943–1987. In Committee to Advise on Australian Immigration Policies, Immigration: a commitment to Australia, consultants reports. Canberra: Australian Government Publishing Service.

Hanson, Pauline (2016). Pauline Hanson’s 1996 maiden speech to parliament: full transcript. Sydney Morning Herald, 15 September. https://www.smh.com.au/politics/federal/pauline-hansons-1996-maiden-speech-to-parliament-full-transcript-20160915-grgjv3.html

Holton, Robert (1998). Globalization and the nation-state. New York: St Martin’s Press.

Isin, Engin, ed. (2008). Recasting the social in citizenship. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Jakubowicz, Andrew (1989). The state and the welfare of immigrants in Australia. Ethnic and Racial Studies 12(1): 1–35. DOI: 10.1080/01419870.1989.9993620

Jones, Gavin (2003). White Australia, national identity and population change. In Laksiri Jayasuriya, David Walker and Janice Gothard, eds. Legacies of White Australia: race, culture and nation, 110–28. Crawley: University of Western Australia Press.

Joppke, Christian (2004). The retreat of multiculturalism in the liberal state: theory and policy. British Journal of Sociology 55(2): 237–57. DOI: 10.1111/j.1468-4446.2004.00017.x

Jordens, Ann-Mari (1997). Alien to citizen: settling migrants in Australia 1945–75. St Leonards, NSW: Allen & Unwin.

—— (1995). Redefining Australians: immigration, citizenship and national identity. Sydney: Hale & Iremonger.

Jupp, James (2002). From White Australia to Woomera: the story of Australian immigration. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

—— (1992). Immigrant settlement policy in Australia. In James Jupp and Gary Freeman, eds. Nations of immigrants: Australia, the United States, and international migration, 130–45. Melbourne; New York: Oxford University Press.

—— (1988). Issues concerning immigrants and immigration. In James Jupp, ed. The Australian people: an encyclopedia of the nation, its people and their origins, 853–963. North Ryde, NSW: Angus & Robertson.

—— (1966). Arrivals and departures. Melbourne: Cheshire-Lansdowne.

Kalantzis, Mary (2000). Multicultural citizenship. In Wayne Hudson and John Kane, eds. Rethinking Australian citizenship, 99–111. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Kerbaj, R. (2006). Radical clerics to be brought in from the cold. Sydney Morning Herald, 31 August.

Kofman, Eleonore (2005). Citizenship, migration and the reassertion of national identity. Citizenship Studies 9(5): 453–67. DOI: 10.1080/13621020500301221

Kymlicka, Will (1995). Multicultural citizenship: a liberal theory of minority rights. New York: Oxford University Press.

—— (1989). Liberalism, community and culture. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Kymlicka, Will, and Keith Banting (2006). Immigration, multiculturalism, and the welfare state. Ethnic and International Affairs 20(3): 281–304. DOI: 10.1111/j.1747-7093.2006.00027.x

Leach, Michael (2000). Hansonism, political discourse and Australian identity. In Michael Leach, Geoffrey Stokes and Ian Ward, eds. The rise and fall of One Nation, 42–57. St Lucia: University of Queensland Press.

Levey, Geoffrey Brahm, and Tariq Modood, eds. (2009). Secularism, religion and multicultural citizenship. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Lopez, Mark (2000). The origins of multiculturalism in Australian politics 1945–1975. Carlton, Vic.: Melbourne University Press.

Megalogenis, George (2006). Keelty: war not fault of Muslims. The Australian, 16 August, 1.

Parliament of Australia (2011) Multiculturalism: a review of Australian policy statements and recent debates in Australia and overseas. Parliamentary Library Research Paper 6 (2010–11). Canberra: Parliament of Australia. https://www.aph.gov.au/About_Parliament/Parliamentary_Departments/Parliamentary_Library/pubs/rp/rp1011/11rp06

Price, Charles (1971). Australian immigration: a bibliography and digest, no. 2. Canberra: Department of Demography, Australian National University.

—— (1966). Australian immigration: a bibliography and digest. Canberra: Department of Demography, Australian National University.

Vasta, Ellie (2005). Theoretical fashions in Australian immigration research. Oxford: Centre on Migration, Policy and Society, University of Oxford.

Zappala, Gianni, and Stephen Castles (2000). Citizenship and immigration in Australia. In Alexander T. Aleinikoff and Douglas Klusmeyer, eds. From migrants to citizens: membership in a changing world, 32–77. Washington DC: Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

Zubrzycki, Jerzy (1995) Arthur Calwell and the origin of post-war immigration. Canberra: Australian Government Publishing Service.

—— (1968). The evolution of the policy of multiculturalism in Australia 1968-1995. Canberra: Department of Social Services, Australian Government.

About the author

Juliet Pietsch is an associate professor of political science, specialising in race and ethnic politics and political sociology. Her recent research focuses on the political integration of migrants and ethnic minorities in Western immigrant countries and South-East Asia. She also researches questions relating to migrant voting patterns, citizenship, migrant political engagement and political socialisation. She has held visiting fellowships at Stanford University and the University of Oxford and has recently completed a book, published by the University of Toronto Press, comparing the political integration of migrants and ethnic minorities in Australia, Canada and the USA.

- Pietsch, Juliet (2024). Multicultural Australia. In Nicholas Barry, Alan Fenna, Zareh Ghazarian, Yvonne Haigh and Diana Perche, eds. Australian politics and policy: 2024. Sydney: Sydney University Press. DOI: 10.30722/sup.9781743329542. ↵

- Parliament of Australia 2011. ↵

- Faulks 1998; Favell 1998; Isin 2008; Kymlicka 1995; Kymlicka and Banting 2006; Levey and Modood 2009. ↵

- Kymlicka 1995; Kymlicka 1989. ↵

- Kymlicka 1995. ↵

- Vasta 2005. ↵

- Jupp 1992. ↵

- Jupp 2002, 23. ↵

- Jakubowicz 1989. ↵

- Jakubowicz 1989; Jordens 1997. ↵

- Dutton 1999. ↵

- Dutton 1999, 14. ↵

- Jordens 1995. ↵

- Zappala and Castles 2000. ↵

- Brawley 1995. ↵

- Jordens 1997, 149. ↵

- Jordens 1997, 13. ↵

- Jakubowicz 1989. ↵

- Jakubowicz 1989; Jupp 1966. ↵

- Jordens 1997. ↵

- Castles et al. 1988. ↵

- Jupp 1966. ↵

- Price 1971; Price 1966; Zubrzycki 1995; Zubrzycki 1968. ↵

- Zubrzycki 1995; Zubrzycki 1968. ↵

- Lopez 2000. ↵

- Lopez 2000, 129. ↵

- Davidson 1997. ↵

- Zappala and Castles 2000, 40. ↵

- Curran 2002, 470. ↵

- Lopez 2000, 222. ↵

- Goot 1988, 8. ↵

- Galbally 1978. ↵

- Jupp 1992. ↵

- Kalantzis 2000, 104. ↵

- Jupp 1992. ↵

- Jupp 1992. ↵

- Jupp 1988, 927. ↵

- Jupp 1992. ↵

- Allbrook, Cattalini and Associates 1989, 20. ↵

- Jones 2003, 116. ↵

- Blainey 1984. ↵

- Blainey 1988, 22. ↵

- Hanson 2016. ↵

- Leach 2000, 45. ↵

- Fincher 2001, 27. ↵

- Fincher 2001, 28. ↵

- Holton 1998; Kofman 2005. ↵

- Kofman 2005, 454–5. ↵

- Kofman 2005. ↵

- Joppke 2004. ↵

- Joppke 2004. ↵

- Albrechtsen 2005. ↵

- Megalogenis 2006, 1. ↵

- Megalogenis 2006. ↵

- Kofman 2005. ↵

- Ang and Stratton 2001. ↵

- Prime Minister John Howard on talkback radio received public criticism for his suggestions that a small section of the Islamic population was unwilling to integrate. See also Kerbaj 2006; letters to the editor in The Weekend Australian, 2–3 September 2006. ↵

- Curran 2002. ↵