Part 2 – Design

16 Introduction to Learning Design: Frameworks and Approaches

Brooke Osborne and Bopelo Boitshwarelo

In a Nutshell

Learning design involves making informed decisions about the types and sequencing of learning activities, the resources to be utilised, and the support and interactions that will occur within the learning environment (Agostinho, 2011). This chapter introduces key learning design frameworks including the ADDIE model, Backward Design, and Universal Design for Learning. These frameworks provide structured approaches to designing effective and inclusive learning experiences.

Why Does it Matter?

Effective learning design is essential for creating educational experiences that are engaging, inclusive, and aligned with desired learning outcomes. By systematically planning and implementing learning activities, resources, and support mechanisms, educators can ensure that students are at the centre of the learning process. This approach not only enhances student engagement and satisfaction but also improves learning outcomes. Understanding and applying robust learning design models helps educators address diverse learner needs and adapt to various educational contexts, ultimately leading to more effective teaching and learning.

What does it look like in practice?

In this section, we explain what learning design is and introduce some frameworks or approaches that can be broadly applied to any learning design situation.

In this section:

- What is learning design?

- Models of learning design

- The ADDIE model

- Backward design

- Universal Design for Learning

- Applying the principles: Checklists

What is learning design?

We engage with the process of learning design when we:

- Make decisions about the type and sequencing of learning activities,

- Identify resources associated with these activities, and

- Specify the type of support and/or interactions learners will have within a learning environment (Agostinho, 2011).

Contemporary approaches to curriculum design emphasise the importance of systematic planning for learning and place students at the centre of the learning experience. For example, Biggs’ activity-centred view of learning focuses on planning for what students do (Biggs & Tang, 2011). In this model, the role of teachers is to communicate and carefully design learning tasks for students to engage with and interpret. Teaching activities and resources exist to support student learning activity (Goodyear, 2015). Therefore, rather than focusing on what teachers do, designing for learning focuses on:

- What learners know,

- What learners need to learn,

- How learners learn it, and

- Learners’ experiences that lead to the intended learning.

For each cohort of students, a typical learning design includes three overlapping areas of focus: content, activity, and support, as shown in Figure 1. These components of learning design, together with their sequencing, ideally operate in a complementary way to facilitate learning and can be used as a guide in planning a course. Examples of learning design templates that employ these principles are available below.

For learning design to be done systematically, it must involve “an application of a pedagogical model for a specific learning objective, target group and a specific context or knowledge domain” (Koper & Olivier, 2004). Thus, any learning design process should be informed by an analysis of the learning needs of the target group; this analysis often results in the formulation of learning objectives (outcomes). In the higher education setting, these learning outcomes are likely determined in advance during the curriculum mapping process.

To help with a systematic design process, pedagogical or learning design models, or frameworks, are often used. There are several models or frameworks that can inform robust learning design, each emphasising different aspects of design. Some are specific to particular perspectives of learning, while others are more generic and accommodate a variety of approaches to learning. In the next section, we introduce three of these generic models.

Models of learning design

Three relevant models and methods commonly used for learning design are:

- The ADDIE model

- Backward design

- Universal Design for Learning

These approaches are not mutually exclusive and, in fact, have many overlaps and draw from the same principles of good educational practice. Where they differ is in their emphasis. The ADDIE model emphasises a systematic and cyclic process of design, while backward design prioritises a clear articulation of the end-goal in the form of intended learning outcomes. Universal Design for Learning recognises that students are diverse and therefore require inclusive teaching practices and learning environments. We recommend using these models eclectically for the best possible learning experience design.

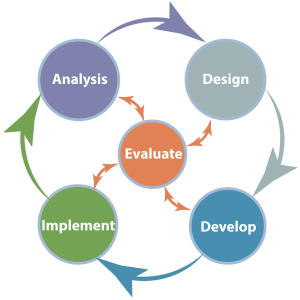

The ADDIE model

The ADDIE model, developed in the 1970s, remains a cornerstone of instructional design (or learning design, as it is now commonly referred to in Australia) worldwide. It is a 5-stage development process, with each step feeding into the next: Analyse, Design, Develop, Implement, and Evaluate. This model isn’t simply descriptive of an idealised process – each step provides guidance to support the development and evaluation of a learning design. While this is the typical sequence of activities, the ADDIE approach is not intended to be linear and/or one directional but tends to be iterative, allowing for formative evaluation at each stage.

Designing for learning typically begins with ADDIE’s Analyse phase. As discussed in Designing or revising a course: Context analysis, this involves gathering information to:

1. Understand who the students are and their characteristics (and what they know or don’t know already),

2. Make visible the specific context in which learning takes place, and

3. Identify the intended learning – what learners must be able to do at the end, so that the whole process can be purposefully designed.

Click on the headings to learn more about each of the ADDIE components:

Analyse (and Understand)

- Know the learners—in order to design learner experiences, you must be able to empathise with the learners.

- Understand the context—learning is context-dependent—understanding the context in which learning occurs helps designers understand learner needs and address them.

- Define the intended learning—Define what learners must be able to do at the end of the process so that the process can be purposefully designed—define the learning outcomes.

Design and Plan – Answer the question: What is the best way to support the intended learning for the target learner group, in context?

- Use ‘backward design’—identify the end goal (learning outcomes) and work backward to where learners are to define the learning process.

- Identify and challenge assumptions about the learners and their activity. Be wary of ‘baggage’ from legacy materials and practices.

- Ask ‘what if’ questions to identify possibilities.

- Whenever possible, make informed choices. What informs your design decisions? What evidence do you have for the design you have chosen?

Develop – Bring the design to life.

- Select (or create) and sequence materials to structure and facilitate learner activity.

- Treat materials and environments as prototypes. Keep asking ‘Will this work?’ and ‘How could this be better?’ If necessary, go back to ‘design’.

- Build the learning environment. Create an infrastructure for successful learning activity.

Implement – Put the design to work.

- Get students working in the learning environment.

- Support their activity within the process.

Evaluate – Did the design work? How can it be improved? What professional development do I need?

- Evaluating and reviewing the student learning journey and the accompanying teaching practices are what enables future enhancements.

- Actively seeking and accepting feedback is important for understanding the impact of your design for learning on the students’ learning experience.

Note that for an already existing task, course, or program that is being re-designed, or for a new task or course which will be incorporated into an already existing context (a course or program), the initial analysis may draw closely on feedback from the review of a previous delivery (in the Evaluate stage). This reflects teaching and curriculum design as a process of continual improvement. Example guides for undertaking a learner and context analysis are provided in the previous chapter, Designing or revising a course: Context analysis.

Backward design

According to the Backward design approach, what guides the Design phase is the question, “What is the best way to support the intended learning for a target learner group in a given context?”

Earlier, we characterised ’designing for learning’ by its concern for what learners need to learn, how learners learn it, and what learner experiences will lead to the intended learning. We also noted that the essential elements of a completed learning design could be organised around three related foci: what students will learn (the content focus, including learning outcomes), what learners will do (the activity focus, including assessment), and what students will need to be successful (the support focus).

The ’backward design’ approach of Wiggins & McTighe (1998) provides a practical guide to planning and designing these elements, including the order in which they should be considered. Backward design prioritises identifying and articulating the intended learning – the specific outcomes (skills, knowledge, attitudes) that students are meant to achieve from the learning experience. This approach is applicable whether designing learning resources, tasks, assessments, courses, or entire programs.

For instance, you might want your students to know how to perform a certain kind of analysis, have a critical understanding of a particular theory and its shortcomings, identify changes in response to a specific economic situation, or gather information using your discipline’s methodology. There are many possibilities, and you might have multiple outcomes for a single class.

Secondly, before considering what content or activities support the required learning, determine what evidence would satisfy you that students have learnt what was needed. This corresponds to the assessment task. Only after this should you plan the learning experiences and supports that will enable the required learning.

This process helps ensure the alignment of learning outcomes, assessment, learning activities, and learning resources, as further discussed in a separate Chapter focusing on Constructive Alignment. (link to chapter)

In summary, the three main stages of the ’backward design’ approach are:

- Identify the desired learning outcomes (What do you want students to learn?)

- Determine acceptable assessment (How will you know students have learned? What evidence will demonstrate this?)

- Plan learning experiences (What will enable students to achieve and demonstrate learning?)

In practice, you might move through these stages in this order, circle back, or use some combination of both. The design process, especially when developing a new course or radically revising an existing course, is often iterative. Work in the later stages may lead one to refine or revise what was done in the early stages.

The Backward design activity is an example of a practical tool that can be used to help review or re-imagine a topic within your course or a specific concept or skill within a topic.

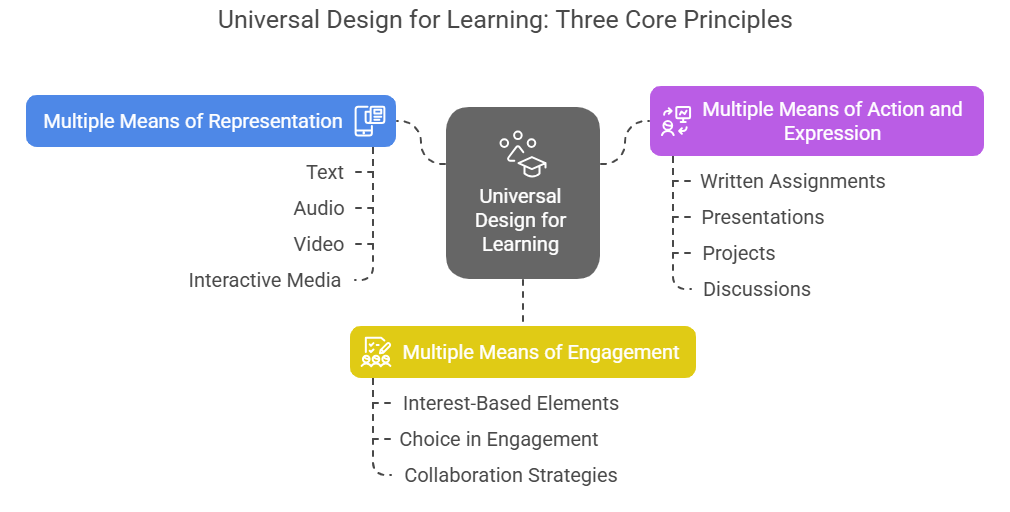

Universal Design for Learning

Universal Design for Learning (UDL) is a framework for designing teaching and learning that recognises diversity among students and seeks to reduce or eliminate potential barriers while maintaining the same standards for all. It enables students to develop knowledge, skills, and enthusiasm for learning by providing a variety of options to cater to diverse abilities and preferences within a cohort. UDL is guided by three principles for learning design:

- Provide multiple means of representation: Offer information and content in different ways. This could involve using various formats such as text, audio, video, and interactive media to cater to diverse learning preferences and needs.

- Provide multiple means of action and expression: Allow multiple ways for students to plan and perform tasks and express their ideas. This includes offering different methods for students to demonstrate their knowledge, such as written assignments, presentations, projects, or discussions.

- Provide multiple means of engagement: Create varied opportunities for learners to become engaged and stay motivated. This can involve incorporating elements that relate to students’ interests, offering choices in how they engage with the material, and using strategies that foster collaboration and interaction.

Explore the UDL Guidelines developed by CAST for greater detail.

At UniSA….

At UniSA, we employ a combination of these models to help us realise a set of principles that guide our curriculum design process. The UniSA curriculum is designed to be:

- Outcome-focused: Achieving graduate qualities and professional learning outcomes.

- Learning-centred: Involving active student learning.

- Flexible: Allowing flexible entry and access to learning.

These aims are reflected in a set of key design principles grounded in learning theory and research on online learning:

| Key Design Principle | Description |

| Reflects an understanding of the learner and learner context | Recognises the diversity of student needs, including the need for flexibility to combine study with multiple other commitments and needs (Stone & Crawford, 2020).

Provides a variety of multimedia options for delivering content, learning activities, and assessment. |

| Consistent & Aligned | Makes explicit to students what they are expected to know and do at the end of the assessment/task/activity/course.

Provides the scaffolding (necessary sequence of learning activities and resources) to enable students to build the expected knowledge and skills. Ensures everything in the course is consistent with these goals (UCF Blended Learning Toolkit, 2011). |

| Interactive & engaging | Develops interactions between students and teachers, and among students themselves (UCF Blended Learning Toolkit, 2011).

Creates activities that require students to engage with the course content and each other (UCF Blended Learning Toolkit, 2011). Promotes cooperation and reciprocity among students (Chickering & Gamson, 1987). Promotes active learning (Chickering & Gamson, 1987). |

| Strong teacher presence | Students need regular and meaningful communication with teachers to remain engaged and connected with their learning community (Stone & Crawford, 2020).

Uses text narrative to foster teacher presence (UCF Blended Learning Toolkit, 2011). |

| Communicates expectations | Explains the rationale for the course design and the relationship between components (UCF Blended Learning Toolkit, 2011).

Makes expectations explicit, specifies students’ responsibilities for undertaking active learning activities, and provides assistance in developing those skills, e.g., discussion forum participation (UCF Blended Learning Toolkit, 2011). Emphasizes time on task (UCF Blended Learning Toolkit, 2011; Chickering & Gamson, 1987). Communicates high expectations (Chickering & Gamson, 1987). |

| Gives timely feedback | Designs opportunities for feedback (UCF Blended Learning Toolkit, 2011).

Gives prompt feedback (Chickering & Gamson, 1987). |

These key principles act as a guiding framework for educators and design teams when collaborating on learning design, as well as a common set of principles for reviewing aspects of a course.

Applying the principles: Checklists

What do these principles look like when applied in a learning design? What are the indicators that a principle has been met or addressed?

Checklists are one means of coming to an agreed understanding about what it means to meet these principles in a given design or situation. They are used as rating tools when reviewing the quality of a course once it has been designed and built, while a set of design principles serve to guide the process of designing and building a learnonline site.

The UniSA Quality Assurance Checklist, for example, has been created at UniSA to support the delivery of learnonline (LO) sites.

There are many sets of design principles and learning checklists available on the web, each displaying different indicators according to their institution’s online teaching and learning priorities. Although not always explicitly stated, all of these can be mapped back to the basic principles of teaching and learning. For further discussion of quality checklists, see also Key elements of an effective course website.

Knowledge Check – What did you learn?

To reinforce what you’ve learned in this chapter, here is an activity focusing on comprehension. Please answer the following questions:

What does it all mean for me?

After reviewing the information in this chapter, reflect on how you can apply these learning design principles to your courses. Consider the following activity to help you integrate these concepts into your teaching practice:

Activity: Design a learning module

Using the frameworks discussed in this chapter (ADDIE, Backward Design, and UDL), design a learning module for one of your courses. Follow these steps:

- Identify the Learning Outcomes: Clearly articulate what you want your students to learn by the end of the module.

- Determine the Assessment: Decide how you will measure whether students have achieved the learning outcomes. Consider what evidence will demonstrate that students have learned what was needed.

- Plan the Learning Experiences: Develop activities, resources, and supports that will enable students to achieve and demonstrate their learning. Ensure these experiences align with the learning outcomes and assessments.

- Apply UDL Principles: Ensure your module provides multiple means of representation (e.g., using various formats such as text, audio, video), multiple means of action and expression (e.g., offering different methods for students to demonstrate their knowledge), and multiple means of engagement (e.g., incorporating elements that relate to students’ interests and fostering collaboration).

- Review and Iterate: Reflect on the designed module and seek feedback from peers or students. Use this feedback to refine and improve the module, ensuring it meets the principles of effective learning design.

References

Agostinho, S. (2011). The use of a visual learning design representation to support the design process of teaching in higher education. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 27(6).

Biggs, J., & Tang, C. (2011). Train-the-trainers: Implementing outcomes-based teaching and learning in Malaysian higher education. Malaysian Journal of Learning and Instruction, 8, 1-19.

Goodyear, P. (2015). Teaching as design. HERDSA review of higher education, 2(2), 27-50.

Chickering, AW & Gamson ZF (1987) Seven Principles for Good Practice in Undergraduate Education,

Washington Center News, Fall, <http://www.lonestar.edu/multimedia/SevenPrinciples.pdf>

Koper, R., & Olivier, B. (2004). Representing the learning design of units of learning. Journal of Educational Technology & Society, 7(3), 97-111.

Stone, C & N Crawford (2020) Three essentials in moving online, NCSEHE <https://www.ncsehe.edu.au/wp- content/uploads/2020/04/3-Essentials-online.pdf >

UCF 2011 Design and Delivery Principles, Blended Learning Toolkit, University of Central Florida, <https://blended.online.ucf.edu/2011/06/07/design-delivery-principles/ >

Wiggins, G., & McTighe, J. (1998). What is backward design. Understanding by design, 1, 7-19.

Further Resources

These resources provide further insights and practical examples that can help you refine your learning design approach.

Australian Universities Teaching Council. (2003). Learning Designs. Retrieved from http://www.learningdesigns.uow.edu.au/index.html.

Biggs, J., & Tang, C. (2011). Teaching for Quality Learning at University: What the Student Does (4th ed.). McGraw Hill, ProQuest Ebook.

Dalziel, J., Conole, G., Wills, S., Walker, S., Bennett, S., Dobozy, E., Cameron, L., Badilescu-Buga, E., & Bower, M. (2016). The Larnaca Declaration on Learning Design. In J. Dalziel (Ed.), Learning Design: Conceptualizing a Framework for Teaching and Learning Online (pp. 1-41). Routledge, London, Taylor & Francis ebooks.

Trigwell, K. (2011). Scholarship of teaching and teachers’ understanding of subject matter. International Journal for the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning, 5(1), Article 1. Available at: https://doi.org/10.20429/ijsotl.2011.050101.

Media Attributions

- Elements of Student-centred Learning Design © Generated using Napkin.ai is licensed under a All Rights Reserved license

- ADDIE diagram © adapted from the Branson document

- UDL: Three core principles © Generated using Napkin.ai is licensed under a All Rights Reserved license

- Private: UniSA Logo