Introduction

The key goals and objectives of this chapter are to understand the following:

- thinking like a sociologist can help us see the complexity of things we take for granted in our everyday lives and better understand why things happen and what their impacts might be

- sociology shares some approaches with other disciplines, and including a sociological approach can enhance your study and practice in areas like social work, psychology, politics, anthropology, science, and more

- the way sociologists think is shaped by the origins of the discipline, but it is relevant to Australia and Aotearoa New Zealand today

- this online textbook has a range of features to help learners of all kinds make sense of a range of sociological areas.

Overview

Every day, about three in every four people in Australia and Aotearoa New Zealand drink at least one cup of coffee. Some make their coffee at home or while they are at work, while others purchase their flat whites, lattes, and cappuccinos from cafes and restaurants. While coffee is probably on our minds a fair bit, rarely do we think too deeply about how we come to drink it, what it means, and how it connects us to others.

Are you a coffee drinker? (If not, ask the same questions about your favourite beverage!) Think back to when you started drinking coffee. Do you remember your first taste? Did you like it right away, or was there some other reason you persisted in drinking it until you developed more of a taste for it? What are your main reasons for continuing to drink coffee regularly – is it about the caffeine hit, the routine, the social aspect of getting a coffee with friends, or something else?

Whether you normally buy your coffee in bean form to brew yourself, or prepared for you from a café, do you think about the way these purchases connect you to others? Think about the networks that are created by your purchase – there are staff at the café or shop you interact with, but also the farmers who produce the coffee beans, and possibly the sugar and milk that goes into your cup, and the people who package and sell those products along the way.

One thing that we are more likely to think about, socially speaking, is the environmental impact of our daily beverage. There has been a lot of attention on disposable coffee cups and their environmental impact. You may have a favourite reusable coffee cup or one that you forget to bring with you when you’re heading to the café. You might try to buy organic beans to support more sustainable practices. Or you might be sceptical of the impact that individual choices like this have on the larger scale. Recently there has even been considered criticism about the use of paper cups, designed to reduce our reliance on plastic ones! (See Carney Almroth et al., 2023).

If any of these thoughts pique your imagination, you might be thinking like a sociologist. Sociologists ask questions like this of our everyday habits to better understand the world around us. Specifically, sociologists consider the interconnectedness of social action with others, as demonstrated by the following video [8:36] by Ben Cushing on the topic of coffee!

What is sociology though? The word “sociology” is derived from the Latin word socius (companion) and the Greek word logos (speech or reason), which together mean “reasoned speech or discourse about companionship”. How can the experience of companionship or togetherness be put into words or explained? While this is a starting point for the discipline, sociology is actually much more complex. It uses diverse theories and methods to understand, study and explore a wide range of subject matter. Like all disciplines, sociology then attempts to apply these studies to the real world.

The object of study therefore for sociologists is the ‘social’. This itself is a rather abstract term, and defining it is difficult. British sociologist Bryan Turner defines the social as firstly “patterns or chains of social interaction and symbolic exchange” (Turner, 2006, p. 136). Secondly, he contends that the social involves, “the patterns of interaction” that inevitably “cohere into social institutions” (Turner, 2016, p. 136). In other words, the social is a range of actions, interactions, relations and importantly institutions and structures that underpin our everyday lives. Sociology’s job is to unpack these, rather messy, worlds that we live in through the systematic and scientific study of all those aspects of life. Turner (2006, p. 136) continues that sociology’s major focuses have been the institutions where we will find the ‘social’ in practice. This includes areas of life like work, the family, nations, religions, law, schooling, health care and other areas where the social has formed ‘institutions’ or structures. Sociology concerns itself with a range of practices including how we relate to one another, how institutions (such as the above) are formed and change over time, how society functions, how we experience different aspects of life (such as politics), and even how we understand ourselves and our identities. The discipline, as you can imagine, sometimes overlaps with other social sciences and sciences such as economics, anthropology, geography, psychology (especially social psychology), and philosophy. As you learn more about sociology in this textbook, you will find some material that comes from other fields of study.

The Sociological Imagination

We use the term sociological imagination to describe the way that we can ask questions of the social world that help us to understand the structures and relationships that surround us. The term was coined by American sociologist C. Wright Mills (1916-1962), who suggested that we cannot understand individuals unless we also understand the society and the structures within them that they emerge from, and vice versa. Mills (1959/2000) directed sociologists’ attention to the relationships between individuals and social systems, and his approach is based on the assumption that studying one without the other would give an incomplete picture. For instance, consider a homeless person that you walk past on the street. We can study their conditions, their choices in life, or choices made for them, to understand how they managed to become homeless. However, this would ignore the broader structures in society that underpin homelessness, such as inequalities in income, policy decisions of governments, welfare systems, and community responses to the public issue. By doing so, we take the individual’s situation and unpack the wider public contexts that led to their current dilemma. In other words, we see the forest from the trees.

The sociological imagination, then, is the capacity to see an individual’s private troubles in the context of the broader social processes that structure them. This enables sociologists to examine what Mills (1959/2000) called ‘personal troubles’ as public issues of social structure and vice versa. Mills reasoned that private troubles like being unemployed, having marital difficulties, or feeling purposeless or depressed can be purely personal in nature. It is possible for them to be addressed and understood in terms of personal, psychological, or moral attributes — either one’s own or those of the people in one’s immediate milieu. In an individualistic society like ours, this is in fact the most likely way that people will regard the issues they confront: “I can’t get a break in the job market;” “My spouse is unsupportive,” and so on. However, if private troubles are widely shared with others, they indicate that there is a common social problem that has its source in the way social life is structured. At this level, the issues are not adequately understood as simply private troubles. They are best addressed as public issues that require a collective response to resolve.

By examining individuals and societies and how they interact through this lens, sociologists are able to examine what influences behaviour, attitudes, and culture. By applying systematic and scientific methods to this process, we try to do so without letting our own biases and preconceived ideas influence our conclusions.

The video below features Australian sociologist Robert van Krieken discussing the sociological imagination and applying it to what we find funny [7:32].

🛠️ Sociological Tool Kit: Activating the Sociological Imagination

Australian sociologist Evan Willis (2011) suggests five questions to help activate the sociological imagination.

These are:

- What is happening?

- Why?

- What are the consequences?

- How do you know?

- How could it be otherwise?

Ask these questions of the following scenario:

Joanna was a 20-year-old university student who was employed part-time at a local coffee shop. She enjoyed the social interactions with people and relied on her pay to finance her accommodation, run her car and pay for groceries. However, in 2020 Australia experienced the start of the COVID-19 pandemic which disrupted the functioning of society as we know it. The government imposed restrictions through a series of lockdowns which included the closure of Joanna’s coffee shop. Joanna lost her job and her financial means of survival and had to move back home to live with her parents. She became anxious and her self-esteem plummeted due to the lack of social connectivity with her previous customers and friends. She began to question herself about her inability to find other jobs despite applying for many jobs online. She desperately needed a solution to her current situation…

Is Joanna’s unemployment in this scenario about her lack of skills and qualifications, or is it linked to broader social issues? Statistics confirm that the proportion of Australians in paid employment dropped in 2020 to the lowest level since 2003 (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2023). If we assume personal troubles are to blame, is the explanation that so many Australians became unworthy of employment all of a sudden? Of course, we know that restrictions related to the COVID-19 pandemic affected the economy, which in turn meant a rise in unemployment and underemployment, and that this especially impacted workers in sectors like hospitality. While Joanna’s self-doubt is understandable, a sociological perspective means we can see the multiple factors that result in her unemployment.

Benefits and Criticisms of a Sociological Perspective

Since the discipline’s creation, scholars and others have contributed to the development of ideas, research methods and theories for the advancement of the discipline’s intellectual foundations. However, many sociologists have used the discipline not simply to understand society but to improve it in different ways. Sociology has thus contributed widely to political, social and policy reforms in issues like equal rights for women in public and private life, the improved understanding and treatment of those with physical and mental disabilities, increased recognition and accommodation for people from different ethnic backgrounds, the development of legislation against ‘hate crimes’, the rights of indigenous populations across the world to preserve their land and culture, and the reforming of prison systems.

Australian sociologist Evan Willis (2011, p. 185) suggests that sociology’s job can feed into the answer for social policy broadly of how we can “achieve the social conditions for the maximum realisation of human potentiality”. Certainly, as listed above, sociology has contributed significantly to the development of policies that attempt to answer this question and more. However, the benefits of thinking sociologically are diverse and wide-ranging.

Sociology challenges the status quo or ‘taken for granted’. It raises a consciousness beyond one’s own existence in everyday life, but also towards the relations we have with others, and their own plights. Willis (2011) describes this as being ‘reflexive‘, which effectively means setting aside one’s own interpretations of the world and experiences of life and trying to step into the shoes of others. Sociologists, as German sociologist Max Weber (1864-1920) once saw it, should be able to understand the plight of others, without actively knowing their lives intimately. In the development of his brand of sociology, which you will discover later is called interpretive sociology, Weber argued that our task is to interpret the actions and understandings of others, not simply ourselves.

Sociology teaches people not to accept easy explanations. It teaches them a way to organize their thinking so that they can ask better questions and formulate better answers. As Willis (2011, p. 34) suggests, a major question we ought to ask ourselves is ‘how do we know?’ This question alone causes us to ponder the different ways people understand the world, and makes us realise not all think the way we do. It increases our willingness to adopt Weber’s position to try to see the world from other people’s perspectives. As a result, sociology allows us to understand others better, thus enabling us to live and work in an increasingly diverse and complicated world. Looking at ourselves and society from a sociological perspective enables us to see how we are connected to different groups based on the many different ways they understand themselves and how society classifies them in turn. It raises awareness of how those classifications — such as economic and status levels, education, ethnicity, or sexual orientation — affect perceptions.

Sociologists are interested in the experiences of individuals and how those experiences are shaped by interactions with social groups and society as a whole. To a sociologist, the personal decisions an individual makes do not exist in a vacuum. Cultural patterns and social forces put pressure on people to select one choice over another. Sociologists try to identify these general patterns by examining the behaviour of large groups of people living in the same society and experiencing the same societal pressures. When general patterns persist through time and become habitual or routinized at micro-levels of interaction, or institutionalized at macro or global levels of interaction, they are referred to as social structures.

Consequently, sociological thinking allows people to become more acutely aware of the suffering and marginalisation others experience in our societies, and globally. As the video above from Cushing showed us, the very things we experience in everyday life can be linked to difficulties and trials others might experience elsewhere in the world. As the chapter on digital sociology will show, the devices that you are using to read this text, have a history going right back to the mining of rare earth minerals (REMs). Unfortunately, the supply chain and production of your phone, laptop or other device is possibly mired in inequality and even potential human rights abuses. The sociological perspective thus encourages us to tackle these difficult issues head-on, revealing their structures, and the institutions that sustain them. In short, as sociologists we have an ability to ensure, and the capacity to unpack, the suffering of other people.

Of course, sociology is not without criticism.

One of the most difficult issues that sociology has to overcome is the nature of social life as messy, difficult to pin down, and of course, ever-changing. Furthermore, defining exactly what the ‘social’ is and how we study it, and understand it, is a matter of opinion as we shall see throughout this textbook. We are, as sociologists, part of the social that we seek to study. As such, a question of bias arises — in that our own interpretations of the world may well colour how we see data, how we understand social dynamics, and how we study society generally. Important questions have arisen over time about the ability of a discipline which emerged from Europe, fundamentally to understand European society, to be imported into places like the antipodes (which is a term used historically in Europe to refer to the lands in the southern hemisphere, and later came to refer to Australia and Aotearoa New Zealand more specifically). As such, sociologists like Australian Raewyn Connell (2007) have argued that sociology needs to be adapted to local issues and integrate the knowledges, theories, concepts and ideas that exist inside different countries and cultures. Everywhere operates differently and distinctly from Europe and North America for her, and sociology needs to change accordingly.

Another major criticism of sociology can come from the advancement of other sciences dedicated to understanding the human condition. Sociology, with the emphasis on the social nature of life, tends to ignore some of these scientific knowledges and theories. In particular, an evolutionary legacy still found in humans in certain behaviours is rather ignored by sociologists in pursuit of other explanations to social action. For instance, researchers in evolution have argued that emotional responses to threats have driven humans forward in the past and still impact us today. Furthermore, neuroscience and cognitive psychology have made significant inroads into explaining some of the dynamics of social life that impact our cognition, how we see the world, and how our brain behaves in response to certain external stimuli. For instance, research on adolescent development of the brain and risk-taking/risk-aversion strategies, where young people in mid-teenage years are prone to taking more risks, is starting to yield some very intriguing results. However, sociology tends to shy away from adopting many of these findings into its work. Mostly due to the nature of the discipline, sociologists often privilege explanations like social conditioning, structures, socialisation, culture and other social issues for behaviour. In sociology’s defence, most disciplines produce these boundaries between their knowledge and understanding of the world and other disciplinary knowledge.

Lastly, sociology (like any academic discipline) does not always speak to the wider social world enough, trapping a lot of its knowledge behind fancy language, difficult-to-understand theories, and complex concepts. Willis (2011) makes this point by arguing that sociology can be rather complicated in how it approaches issues both in terms of methodology, but also in terms of the style of writing we adopt. Furthermore, sociology for American Michael Burawoy (2005) needs to step forward in defence of civil society more and become ‘public’, researching issues that affect the population and those in marginalised spaces, and using the knowledge and expertise within the discipline to improve lives, rather than simply ‘navel gazing’ for career or professional improvements. However, despite these criticisms, sociology as a discipline continues to flourish not only across the major nation-states in Europe and America, but also here in the antipodes.

Where Sociology Comes From

You could say that humans have been fascinated by the nature of society, and the relations between each other, for centuries. Ancient philosophers from the Middle East, Asia, and of course the Greeks, have all laboured over the human condition, and how we understand our worlds. For the Greeks in particular, how, not just what, we know about the world has echoed through the ages until we reached enlightenment, where disciplines like sociology and others were born. For instance, the philosophical study of the nature of life, our limitations and our perceptions and knowledge of the world around us, called epistemology, started with Aristotle (384-322BC) and continues to this day in sociology. We shall revisit this in the chapter on social research methods.

The discipline of sociology itself does not emerge in name, though, until the 19th century with the ever-increasing push for enlightenment in the West, particularly in Europe. During this time, traditional interpretations of life had begun to lose their ability to explain the world. Traditional institutions such as religion were losing ground to the increasing push for scientific knowledge. Myths, superstitions, and the ‘irrational’ as Max Weber would describe it, lost traction, replaced with the cold and calculated scientific method and the ever-expanding economic system of capitalism. It was also during this time that the church, as the legitimate intellectual authority of a state, was replaced by the nation-state. Of course, the French Revolution (1775-1783, and 1789-1799) also severed ties in France from the monarchy and created a push across Europe for democracy. Technology, through the Industrial Revolution, was also transforming much of how we did life, including labour. As a consequence, European societies were rapidly changing, and what we call modernity had kicked off in earnest.

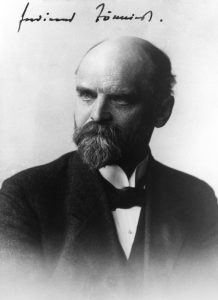

Sociology was born out of these contexts, which is important to understand. In particular, theorists like the French philosopher Auguste Comte (1798-1857) and the Englishman Herbert Spencer (1820-1903) were increasingly intrigued by the sciences of the time and argued for a ‘science of society’ to emerge that would be called sociology (see next chapter). Sociology, as a disciplinary knowledge and science, took hold in mostly French and German universities to begin with, rapidly developing different methods and theories associated with understanding society. During this time of great upheaval and concern in Europe, sociologists rose to prominence in their attempt to understand changes to society. For instance, Emile Durkheim (1858-1917), who is largely considered a forefather of French sociology, became increasingly concerned with the rapid rise of capitalism, the growth of the cities, and the loss of religion. In particular, Durkheim worried that life was increasingly individualised. In other words, people were less connected to their communities than ever before, leading him to increased risk of individuals feeling isolated and alone. Durkheim wanted sociology to fulfil the role of ensuring this was reversed, and that society was cohesive, and bound together. Others, like the German Ferdinand Tönnies (1855-1936), argued that society was transitioning from what he called Gemeinschaft (community), bound by traditional values and community-mindedness, to Gesellschaft (society), where self-interest and rational thinking dominated. This is especially seen in the transformation of cities into larger metropolises where population sizes grew, capitalism took hold, and bureaucracies became the organising institutions of our lives.

Sociology grew in popularity and size during this time due to the work of the aforementioned theorists such as Max Weber and Emile Durkheim. Over time, and through the influence of others like Karl Marx (1818-1883), Harriet Martineau (1802-1876), W.E.B Du Bois (1868-1963), Jane Addams (1860-1935), and Charles Cooley (1864-1929), sociology adopted different focuses from the consideration of social injustices, through to deeper concerns with the nature of society, and the everyday interactions that make up life. What you will find as you progress through this textbook, is the distinct impression that sociology is not just a one-size fits all discipline. The knowledges, methods and theories are diverse. As mentioned above, the reason for this is rather simple. Society is a complicated thing! As humans, we all have different backgrounds, situations, contexts and geographies that make up who we are individually and collectively. Consequently, sociology was destined to never be simple. As you find in this introduction to the discipline, there are many approaches across the world, including in Australia and Aotearoa New Zealand, that continually develop to make the best sense of our social world.

A Word on Theory

Sociologists focus their studies on a range of social processes, events, and dynamics. As noted above, sociology began as an attempt to create a science of society, hence why it belongs in the social sciences today alongside other cognate disciplines like anthropology, geography and demography. As a result, sociology has developed a range of methods to obtain data on social life – we explore these in detail in the social research methods chapter. However, sociology also has a significant amount of theory embedded in its knowledge base.

Theory comes from the Latin theoria and the Greek theōria which effectively means to contemplate, speculate, consider or look at. As the word evolved in the English language over time, it denoted something more specific, such as explaining phenomenon based on intellectual reasoning and observing. Today, you could argue, we all theorise about the world around us using our background knowledge, our thoughts, our experiences and our social encounters. However, sociologists have long used theory as a way to make sense of the world intellectually, through observation and at times data. Max Weber was perhaps one of the earliest ‘theorists’ of his time, arguing in particular that sociology ought to understand, observe and theorise the transformations of society through history to the present day. He wanted us to be historically aware of the way something like the family was orientated in the past, and how it had changed to the present to mean something different. This required understanding how culture, religion, the government, economy and law (along with other institutions) challenged, shaped and altered the status quo.

While not as important for you to understand for this textbook, there is a difference between what we might term ‘social theory’ and ‘sociological theory’. Social theory is closely aligned with philosophy as a cognate discipline and underpins many of the different disciplines inside the social sciences generally. For instance, Karl Marx’s theory of capitalism and the relationship between individuals and class has had significant influence on a variety of areas, not just sociology. This includes political science, geography, cultural studies and anthropology. Sociological theory, on the other hand, tends to emerge from sociology itself and relies more exclusively on objectivity, science, and impartiality. An example of sociological theory would be Talcott Parsons’ (1951/2013) attempt to understand how society operates functionally in America. His theory was founded on observation of life generally in modernity, theory from others including Durkheim, and on how society operates across institutions from the family to government, in what he later called structural functionalism. In this textbook, you will come across a range of ‘theories’ – some are social theories, others are sociological theories, and others still (like the symbolic interactionists) are blurred between both. While it is not important for you to demarcate between the two, it is important to recognise that social theory does at times feed into multiple social sciences, which is why in other subjects you might encounter similar ideas!

Consequently, in the chapters that follow you will engage with many of these theories, paradigms and ideas. Each chapter will provide overviews of these within different and distinct sociological topics. It is vitally important that you understand you do not have to agree with anyone’s theories in this book! We encourage you to think of what follows as nothing more than a broad outline of how different sociologists understand society. Do not let yourself be too constrained by these theories, and think critically about all of them. In the end, our task is to teach you what these different people have argued over time and how to understand their research and theories. Your task is to learn, grow and think reflexively about them all. We hope that with your teachers and classmates, you will appreciate the complexity of sociology, and make up your own mind about who might be right or wrong.

How to Use This Book

This online textbook has a number of features that we hope you’ll find useful as you study sociology. We start each chapter with some key learning objectives – the important takeaways that you should quiz yourself on if you want to check your understanding. We finish each chapter with a summary of those key objectives. Across the chapters, we have different sections that allow you to dig deeper, learn more specifically, and introduce you especially to cases that are unique to Australia and Aotearoa New Zealand.

🧠 Learn More

A good strategy while studying is to put things in your own words. This can help you grasp the real meaning of a concept, which then lets you level up and apply something outside of the context in which you are learning it. Of course, you need to ensure you still reference the original source of the ideas, but saying something differently is a great way to learn it. Explore more study tips for university students on the Studying 101: Study Smarter Not Harder web page.

As an online textbook, we have tried to include links to further information, for example about the life and work of theorists you should know about. The textbook has embedded videos that you can watch to hear and see explanations of some of the material you are also reading about. In particular, keep your eye out for these features that you can find in most chapters:

🔍 Look Closer

These boxes provide you with case studies or deep dives that illustrate the ideas in that chapter. In particular, we try to engage with you with the research and cases that reflect Australia and Aotearoa New Zealand.

🛠️ Sociological Tool Kit

You’ve seen this one already in this chapter. When you see the Sociological Tool Kit, you will get an explanation of a particular concept or tool that sociologists use, and some questions for you to consider or discuss with classmates or in your own studies.

🧠 Learn More

These shaded blue boxes are usually a brief mention of something you might investigate further if you are interested in this topic, usually with a link out to kickstart your independent learning – like the one just above.

🎞️ Sociology on Screen

If you’re anything like us, you probably watch TV and movies pretty regularly, or maybe you grew up watching them. If so, this box is for you! In some chapters, we highlight movies and shows that illustrate the topics we discuss. If you have not yet seen the things we refer to, you might consider seeking them out and watching with your sociological imagination activated.

Finally, we had to put the book in some kind of order, but use it in the way that best suits your learning. You might interact with later chapters in the book before early ones. You might read the Summary of the chapter before reading the chapter itself. You might move through all the activity boxes before reading the paragraphs. The joy of learning is figuring out what works best for you. In addition, all references from the text are provided at the end of the chapter for you to find, read and investigate.

In Summary

- The sociological imagination is a way of seeing the world that links individual experiences with the processes of social systems and structures, and we can use it to understand everything from unemployment to catching up with friends for coffee.

- Sociologists ask questions about the links between people and institutions and does not rely on simplistic explanations of phenomena, which makes it a useful perspective to combine with other fields of study.

- Sociology emerged as a discipline in the context of the scientific turn, the Enlightenment, and the Industrial Revolution, and this context still shapes how the discipline understands the world around us. However, its continued use by scholars in Australia and Aotearoa New Zealand demonstrates that the discipline is still very important for understanding contemporary societies.

- We have included features in this textbook that should help a variety of learners make the most of their studies in sociology, including activities, links, and videos alongside the text.

References

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. (2023). Health across socioeconomic groups. Canberra.

Burawoy, M. (2005). For public sociology. American Sociological Review, 70(1), 4-28. https://doi.org/10.1177/000312240507000102

Carney Almroth, B., Carle, A., Blanchard, M., Molinari, F., & Bour, A. (2023). Single-use take-away cups of paper are as toxic to aquatic midge larvae as plastic cups. Environmental Pollution, 330, Article 121836. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2023.121836

Connell, R. (2007). Southern theory: The global dynamics of knowledge in social science. Routledge.

Mills, C. W. (2000). The sociological imagination (40th anniversary ed.). Oxford University Press. (Original work published 1959)

Parsons, T. (2013). The social system. Routledge. (Original work published 1951)

Turner, B. S. (2006). Classical sociology and cosmopolitanism: A critical defence of the social. The British Journal of Sociology, 57(1), 133-151. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-4446.2006.00097.x

Willis, E. (2011). The sociological quest: An introduction to the study of social life (5th ed.). Allen & Unwin.

The term created by American sociologist C. Wright Mills to define the task of sociology to look beyond the private troubles of individuals and widen the scope to the connectedness of their experiences to public issues. For example, homelessness is a private or individual issue, that we can look at individually – or we can broaden this out and examine the social conditions that create homelessness.

Refers to the process through which a researcher consistently reflects on their position in the research and their ability to potentially influence results via their own preconceived ideas, worldviews and theories.

An approach within social science theories that argues the social world cannot be understood through natural sciences. Rather, society is messy and complex and research can only obtain an understanding of how people interpret or perceive the world around them.

An approach to research that involves making hypotheses or predictions, and then testing these via empirical work mostly via statistics, which then either prove or disprove the hypothesis.

An economic system that dominates the world today in which society's economic activity is organised around trade for profit and private property.

A bounded geographical territory that is ruled over by a government in the name of a community or nation. For example, Australia is governed by the Australian Government that represents the will of the Australian community.

Refers to the time period where Europeans in particular began to dramatically and quickly change the organisation of society, culture and economy. This included the rise of the nation-state, rationalism, science, organised labour and the intensification of urbanisation and growth of cities. Sociological figures refer to modernity demarcate it from pre-modern times where societies were arranged far differently.