Social Movements and Social Change

Theresa Petray

The key goals of this chapter are to explain that:

- social movements are one form of non-routine collective action focused on correcting injustices

- there are many types of social movements and many activities they may engage in

- key approaches to understanding social movements include resource mobilisation theory, framing, and new social movement theory

- while social movements are an important contemporary way of bringing about social change, they are not the only way that change happens.

Overview

In May 2020, most countries around the world were in the first few months of the COVID-19 pandemic, and restrictions on movement to stop its spread. But this time period also saw the largest racial justice protests in the United States since the Civil Rights Movement in the 1960s, in response to the murder of George Floyd by a police officer in May 2020 (we also discuss this movement in the chapter on race, ethnicity and indigeneity). The Black Lives Matter movement was reactivated despite pandemic restrictions, and large protests were held around the world (Silverstein, 2021). In the months that followed, Washington, DC, became a locus of the movement in the US, with a formal gathering place named Black Lives Matter Plaza (Gottbrath, 2020).

In Aotearoa New Zealand, Black Lives Matter protests were held at the same time as a trial of arming police officers, which caused considerable concern amongst Maori, Pasifika, and Black people in the country. Protests in Aotearoa New Zealand explicitly focused on the risks of arming police, and a few days after the first Black Lives Matter protests, the government announced it would not go ahead with arming police (Silverstein, 2021).

In Australia, Black Lives Matter led to protests against Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander deaths in custody but also brought attention to racism more broadly—including the increased risks that First Nations people had of COVID-19 complications (Bond et al., 2020).

What causes large groups of people to come together in the ways that we saw in response to this murder—even in the face of very real public health concerns at the time? How does something like this spread beyond the city where the initial event happened, and even around the world? What role does group activity like protest have in changing society? This chapter will help you understand these protests, and others, through a focus on collective behaviour, social movements, and social change.

Collective Behaviour

People sitting in a café in a touristy corner of Sydney might expect the usual sights and sounds of a busy city. They might be more surprised when, as they sip their espressos, hundreds of people start streaming into the picturesque square clutching pillows, and when someone gives a signal, they start pummelling each other in a massive free–for–all pillow fight. Spectators might lean forward, coffee forgotten, as feathers fly and more and more people join in. All around the square, others hang out of their windows or stop on the street, transfixed, to watch. After several minutes, the spectacle is over. With cheers and the occasional high-five, the crowd disperses, leaving only destroyed pillows and clouds of fluff in its wake.

This is a flash mob, a group of people who gather for an unexpected activity that lasts a short time before returning to their regular routines. Flash mobs emerged as a deliberate action with a name in 2003, relying on emails and text messages to gather a crowd (Corry, 2021). Today, the more common version is a TikTok meme—a handful of people performing a choreographed dance in a train station, shopping centre, or on a city street.

Technology plays a big role in these events. They are often captured on video and shared on the internet; frequently they go viral and become well known. What leads people to want to flock somewhere for a massive pillow fight? Or for a choreographed dance? Or to freeze in place? In large part, it is as simple as the reason humans have bonded together around fires for storytelling, danced together, or joined a community holiday celebration. Humans seek connections and shared experiences.

Flash mobs are examples of non-routine collective action, non-institutionalised activity in which groups of people voluntarily engage. There are four primary forms of collective behaviour: the crowd, the mass, the public, and social movements.

It takes a fairly large number of people in close proximity to form a crowd (Lofland, 1993). Examples include a group of people attending a Harry Styles concert, attending Mardi Gras festivities, or joining a worship service. Turner and Killian (1993) identified four types of crowds.

- Casual crowds consist of people who are in the same place at the same time, but who are not really interacting, such as people standing in line at the post office.

- Conventional crowds are those who come together for a scheduled event, like a religious service or rock concert.

- Expressive crowds are people who join together to express emotion, often at funerals, weddings, or the like.

- The final type, acting crowds, focus on a specific goal or action, such as a protest movement or riot.

In addition to the different types of crowds, collective groups can also be identified in two other ways (Lofland, 1993). A mass is a relatively large and dispersed number of people with a common interest, whose members are largely unknown to one another and who are incapable of acting together in a concerted way to achieve objectives. In this sense, the audience of the television show Game of Thrones or of any mass medium (TV, radio, film, books) is a mass. A public, on the other hand, is an unorganised, relatively diffused group of people who share ideas on an issue, such as social conservatives. While these two types of crowds are similar, they are not the same. To distinguish between them, remember that members of a mass share interests whereas members of a public share ideas.

Some collective behaviour is considered routine, like voting and lobbying, which may contribute to social change even though they are within formal institutional structures. However, there are times when ‘usual conventions cease to guide social action and people transcend, bypass, or subvert established institutional patterns and structures’ (Turner & Killian 1957/1987, p. 3). It is in these moments where non-routine collective action emerges.

Theories of Collective Behaviour

Early collective behaviour theories (Blumer, 1969; Le Bon, 1895/1960) focused on the irrationality of crowds. Le Bon saw the tendency for crowds to break into riots as a product of the properties of crowds themselves: anonymity, contagion, and suggestibility. On their own, no one would be capable of acting in this manner, but as anonymous members of a crowd they were easily swept up in dynamics that carried them away. Eventually, those theorists who viewed crowds as uncontrolled groups of irrational people were supplanted by theorists who viewed the behaviour of some crowds as the rational behaviour of logical beings.

Emergent Norm Theory

Sociologists Ralph Turner and Lewis Killian (1993) built on earlier sociological ideas and developed what is known as emergent norm theory. They believe that the norms experienced by people in a crowd may be disparate and fluctuating. They emphasise the importance of these norms in shaping crowd behaviour, especially those norms that shift quickly in response to changing external factors. Emergent norm theory asserts that, in this circumstance, people perceive and respond to the crowd situation with their particular (individual) set of norms, which may change as the crowd experience evolves. This focus on the individual component of interaction reflects a symbolic interactionist perspective.

For Turner and Killian, the process begins when individuals suddenly find themselves in a new situation, or when an existing situation suddenly becomes strange or unfamiliar. Once individuals find themselves in a situation ungoverned by previously established norms, they interact in small groups to develop new guidelines on how to behave. According to the emergent-norm perspective, crowds are not viewed as irrational, impulsive, uncontrolled groups. While this theory offers insight into why norms develop, it leaves undefined the nature of norms, how they come to be accepted by the crowd, and how they spread through the crowd.

Value-Added Theory

Neil Smelser’s (1962) meticulous categorisation of crowd behaviour, called value-added theory, is a perspective within the functionalist tradition based on the idea that several conditions must be in place for collective behaviour to occur. Each condition adds to the likelihood that collective behaviour will occur.

The first condition is structural conduciveness, which describes when people are aware of the problem and have the opportunity to gather, ideally in an open area. Structural strain, the second condition, refers to people’s expectations about the situation at hand being unmet, causing tension and strain. The next condition is the growth and spread of a generalised belief, wherein a problem is clearly identified and attributed to a person or group. Fourth, precipitating factors spur collective behaviour; this is the emergence of a dramatic event. The fifth condition is mobilisation for action, when leaders emerge to direct a crowd to action. The final condition relates to action by the agents of social control. Called social control, it is considered the only way to end the collective behaviour episode (Smelser, 1962).

While value-added theory addresses the complexity of collective behaviour, it also assumes that such behaviour is inherently negative or disruptive. In contrast, collective behaviour can be non-disruptive, such as when people flood to a place where a leader or public figure has died to express condolences or leave tokens of remembrance. People also forge momentary alliances with strangers in response to natural disasters.

Assembling Perspective

Interactionist sociologist Clark McPhail (1991) developed the assembling perspective, another system for understanding collective behaviour that credited individuals in crowds as rational beings. Unlike previous theories, this theory refocuses attention from collective behaviour to collective action. Remember that collective behaviour is a non-institutionalised gathering, whereas collective action is based on a shared interest. McPhail’s theory focused primarily on the processes associated with crowd behaviour, plus the life cycle of gatherings. He identified several instances of convergent or collective behaviour, summarised below.

| Type of crowd | Description | Example |

| Convergence clusters | Family and friends who travel together | Carpooling parents take several children to the movies |

| Convergent orientation | Group all facing the same direction | A semi-circle around a stage |

| Collective vocalisation | Sounds or noises made collectively | Screams on a roller coaster |

| Collective verbalisation | Collective and simultaneous participation in a speech or song | Singing along at a Taylor Swift concert |

| Collective gesticulation | Body parts forming symbols | Dancing the haka at a football game |

| Collective manipulation | Objects collectively moved around | Holding signs at a protest rally |

| Collective locomotion | The direction and rate of movement to the event | Children running to an ice cream truck |

As useful as this is for understanding the components of how crowds come together, many sociologists criticise its lack of attention on the large cultural context of the described behaviours, instead focusing on individual actions. Moreover, how do we understand collective behaviour that is expressly seeking to participate in social change processes? For that, we turn to the sociological study of social movements.

Sociology of Social Movements

Social movements are purposeful, organised groups striving to work toward a common goal. These groups might be attempting to create change, to resist change, or to provide a political voice to those otherwise disenfranchised. Social movements are based on the perception of injustices — we say perception, here, not to downplay the seriousness of the things a social movement is responding to! But rather, an injustice must be perceived as a problem, and people need to believe that change is possible, in order for a social movement to emerge.

You may have learned about social movements in history classes—the Civil Rights movement, for example. But we tend to take for granted the fundamental changes they caused. And contemporary movements create social change on a global scale. Movements happen in our towns, in our nation, and around the world, especially since modern technology has allowed us a near-constant stream of information about the quest for social change around the world.

🧠 Learn More

The article Social Movements—and Their Leaders—That Changed our World lists several key individuals—social movement leaders—who have changed the world in recent history. The article, while not exclusively focused on the United States of America, does pay more attention to leaders from the US than anywhere else. What social movement leaders from Aotearoa New Zealand or Australia would you add to the list? What social movements are missing from the list?

Consider the relationship between individual leaders and the collective effort of social movements. As a society we often pay attention to the individuals, but how successful would they be if they did not have a movement of many other supporters working with them?

One set of social movements that have been strongly linked to modern communications technologies is known as the Arab Spring. In January 2011, Egypt erupted in protests against the stifling rule of long-time President Hosni Mubarak. The protests were sparked in part by a revolution in Tunisia that began in December 2010, and, in turn, they inspired demonstrations throughout the Middle East in Libya, Syria, and beyond. This wave of protest movements travelled across national borders and seemed to spread like wildfire. There have been countless causes and factors in play in these protests and revolutions, but many have noted the internet-savvy youth of these countries. Some believe that the adoption of social technology—from Facebook pages to mobile phone cameras—that helped to organise and document the movement contributed directly to the wave of protests called Arab Spring. The combination of deep unrest and disruptive technologies meant these social movements were ready to rise up and seek change.

Since the start of the Arab Spring, only Tunisia has successfully transitioned to a democratic government with constitutionally-protected basic rights. Other countries have fallen into civil wars, or remain ruled by authoritarian regimes. However, Khondker (2019) argues that this doesn’t mean that the revolutions of the Arab Spring failed, necessarily. There have been significant social improvements in the region, and it is likely that these protests will have long-term impacts on how people understand their agency and ability to resist government power.

Types of Social Movements and Activism

Earlier studies of social movements differentiated between two main types of movements. First, integrationist, or liberal, movements are those seeking change to existing systems. In contrast, anti-systemic, or radical, movements seek to replace that system with a new one. Anti-systemic movements are further broken down as either social movements or national movements (Wallerstein, 2002). In the 1970s, social movements were thought of as those focused on class struggle, like trade unions and socialist parties. National movements were those seeking to create nation-states, through secession, decolonisation, or federation.

More recently, the authors of this book, sociologists Theresa Petray and Nick Prendergrast (2018), identified an additional category of social movements. In addition to integrationist and anti-systemic movements, they added non-hegemonic movements to the discussion. While the first two are focused on states—reforming them, or overhauling them—the latter seeks to create localised change without engaging at all with existing structures. In other words, non-hegemonic activism focuses on “small-scale experiments in a different kind of society” (Petray & Pendergrast, 2018, p. 668).

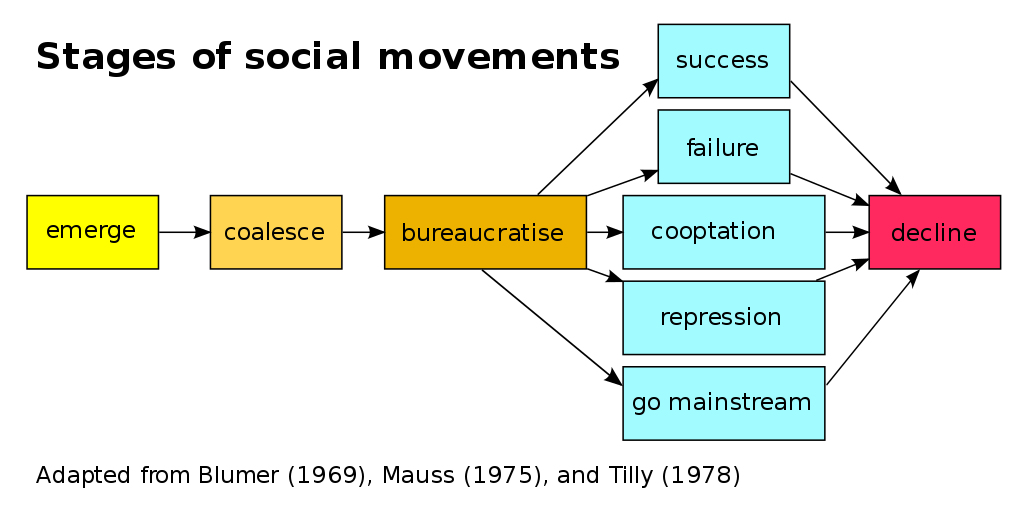

Some research is interested in the life cycle of social movements—how they emerge, grow, and in some cases, die out. Blumer (1969) and Tilly (1978) outline a four-stage process. In the preliminary stage, people become aware of an issue and leaders emerge. This is followed by the coalescence stage when people join together and organise in order to publicise the issue and raise awareness. In the bureaucratisation stage, the movement no longer requires grassroots volunteerism: it is an established organisation, typically peopled with a paid staff. At this point, a movement may experience success or failure, it may be co-opted by power structures, it may face repression, or it might become mainstream. Generally what follows is the decline stage.

🔍 Look Closer: Social Movements and Social Media

Chances are you have been asked to tweet, share, like, or donate online for a cause. Or maybe you follow political candidates and activists on Instagram and share their posts to your stories. Perhaps you have “liked” a local non-profit on Facebook, prompted by one of your neighbours or friends liking it too. Nowadays social movements are woven throughout our social media activities.

Social media has the potential to dramatically transform how people get involved. Look at the first stage in the life cycle of social movements, the preliminary stage: people become aware of an issue and leaders emerge. Social media speeds up this step. Suddenly, a shrewd TikTok-er can alert thousands of followers about an emerging cause or an issue on their mind. Issue awareness can spread at the speed of a click, with thousands of people across the globe becoming informed at the same time. In a similar vein, those who are savvy and engaged with social media emerge as leaders. Suddenly, you do not need to be a powerful public speaker. You do not even need to leave your house. You can build an audience through social media without ever meeting the people you are inspiring.

At the next stage, the coalescence stage, social media also is transformative. Coalescence is the point when people join together to publicise the issue and get organised. U.S. President Obama’s 2008 campaign became a case study in organising through social media. Using Twitter and other online tools, the campaign engaged volunteers who had typically not bothered with politics and empowered those who were more active to generate still more activity. It is no coincidence that Obama’s earlier work experience included grassroots community organising. What is the difference between this type of campaign and the work that political activists did in neighbourhoods in earlier decades? The ability to organise without regard to geographical boundaries becomes possible using social media. In 2009, when student protests erupted in Tehran, social media was considered so important to the organising effort that the U.S. State Department actually asked Twitter to suspend scheduled maintenance so that a vital tool would not be disabled during the demonstrations.

What is the real impact of this technology on the world? Did Twitter bring down Mubarak in Egypt? Author Malcolm Gladwell (2010) does not think so. In the article “Small Change“, in The New Yorker magazine, Gladwell tackles what he considers the myth that social media gets people more engaged. He points out that most of the tweets relating to the Iran protests were in English and sent from Western accounts (instead of people on the ground). Rather than increasing engagement, he contends that social media only increases participation; after all, the cost of participation is so much lower than the cost of engagement. Instead of risking being arrested, shot with rubber bullets, or sprayed with fire hoses, social media activists can click “like” or retweet a message from the comfort and safety of their desk (Gladwell, 2010).

Do you agree with Gladwell, or do you see the potential for social media to contribute more directly to social change?

The term that is generally used to describe what social movements do is activism. The term ‘activism’ has lots of baggage and meaning in our societies. Many people think of activism and protest as synonyms, but in fact, protest is just one kind of activism. Protest—marches or rallies where groups of people gather to demonstrate their commitment to a cause or issue—can be a bit more confrontational, a lot more visible, and sometimes more challenging to norms than other forms of activism, and for these reasons it attracts more media attention.

Other forms of activism are just as important for social movements, though. These include things like

- advocacy, where movement participants work with specific people or communities experiencing disadvantage in order to improve their circumstances,

- lobbying, where movement participants seek to influence formal politics through letter writing, or meeting with politicians or bureaucrats,

- education and outreach, where movement participants work to increase awareness of their cause amongst the general public, using various methods,

- celebrations and commemorations, where movements acknowledge wins, and recognise their history as a social movement, and

- prefiguration, where movement participants establish the alternatives they seek more broadly. This form of activism is especially relevant to the non-hegemonic movements that we have discussed above.

🎞️ Sociology on Screen

Protest is usually the kind of activism that most people are aware of, partially because of how the media and popular culture portray social movements. We can see protest at the centre of works like Les Miserables, which culminated in the Paris Uprising of 1832, with protesters responding to poverty, disease, and inequality. The stage and screen depictions of Les Miserables feature protesters establishing barricades and fighting against the army. Other movies like Pride (released in 2014), The Hate U Give (released in 2018), and Selma (released in 2014) tell the stories of more recent social movements. When activism is present on TV shows and in movies, what kinds of activism are we most likely to see? What is missing from a more sensationalised version of a social movement?

Theoretical Perspectives on Social Movements

Social movements have, throughout history, influenced societal shifts. Sociology looks at these moments through the lenses of three major perspectives.

The functionalist perspective looks at the big picture, focusing on the way that all aspects of society are integral to the continued health and viability of the whole. A functionalist might focus on why social movements develop, why they continue to exist, and what social purposes they serve. On one hand, social movements emerge when there is a dysfunction in the relationship between systems. The labour union movement developed in the 19th century when the economy no longer functioned to distribute wealth and resources in a manner that provided adequate sustenance for workers and their families. On the other hand, when studying social movements themselves, functionalists observe that movements must change their goals as initial aims are met or they risk dissolution.

The critical perspective focuses on the creation and reproduction of inequality. Someone applying the critical perspective would likely be interested in how social movements are generated through systematic inequality, and how social change is constant, speedy, and unavoidable. In fact, the conflict that this perspective sees as inherent in social relations drives social change. For example, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) was founded in the United States in 1908. Partly created in response to the horrific lynchings occurring in the southern United States, the organisation fought to secure the constitutional rights guaranteed in the 13th, 14th, and 15th amendments, which established an end to slavery, equal protection under the law, and universal male suffrage (NAACP, 2011). While those goals have been achieved, the organisation remains active today, continuing to fight against inequalities in civil rights and to remedy discriminatory practices.

The symbolic interactionist perspective studies the day-to-day interaction of social movements, the meanings individuals attach to involvement in such movements, and the individual experience of social change. An interactionist studying social movements might address social movement norms and tactics as well as individual motivations. For example, social movements might be generated through a feeling of deprivation or discontent, but people might actually join social movements for a variety of reasons that have nothing to do with the cause. They might want to feel important, or they know someone in the movement they want to support, or they just want to be a part of something. Have you ever been motivated to show up for a rally or sign a petition because your friends invited you? Would you have been as likely to get involved otherwise?

🔍 Look Closer: School Strikes for Climate

In 2018, Swedish 15-year-old Greta Thunberg held a three-week sit-in on the steps of the Swedish Parliament instead of attending school. Following the Swedish election at the end of the three-week protest, Thunberg continued to hold a weekly sit-in on Fridays. This action inspired other Swedish young people to join her, and in November 2018, sparked the global School Strike For Climate. In Australia, school strikes were held in November 2018, March 2019, and periodically since then (Alexander et al., 2022).

How would each theoretical perspective seek to understand this social movement?

A functionalist perspective might focus on the societal dysfunction that leads to young people feeling so concerned about the risks of climate change to protest by going on strike from school. This perspective might consider the disruption in social norms, which typically see young people trusting in the authority of adults, including politicians—but in the case of the School Strike for Climate, this trust appears to be eroding.

A critical perspective would likely include an analysis of the lack of power that young people hold in society, particularly relative to politicians and corporations responsible for mainstream responses to climate change. This conflict between young people worrying about the future of the planet and powerholders with economic and political interests might be viewed as a key method for changing existing power dynamics, according to this critical perspective.

Understanding the School Strikes through a symbolic interactionist lens might focus instead on the images, symbols, and slogans on the protest signs at the School Strike events. For example, the sign in the image below refers to a celebrity, Gigi Hadid, and one in the background refers to Twilight character Edward Cullen. In the image at the top of this box, one sign is designed to look like the periodic table of elements. Symbolic interactionists might consider the meanings attached to, and communicated by, such protest signs.

More specifically, here we will showcase three specific theories used to understand social movements.

Resource Mobilisation Theory (RMT)

Social movements will always be a part of society as long as there are aggrieved populations whose needs and interests are not being satisfied. However, according to Resource Mobilisation Theory, grievances do not become social movements unless social movement actors are able to create viable organisations, mobilise resources, and attract large-scale followings. As people will always weigh their options and make rational choices about which movements to follow, social movements necessarily form under finite, competitive conditions: competition for attention, financing, commitment, organisational skills, etc. Not only will social movements compete for our attention with many other concerns—from the basic (our jobs or our need to feed ourselves) to the broad (video games, sports, or television), but they also compete with each other. To be successful, social movements must develop the organisational capacity to mobilise resources (money, people, and skills) and compete with other organisations to reach their goals.

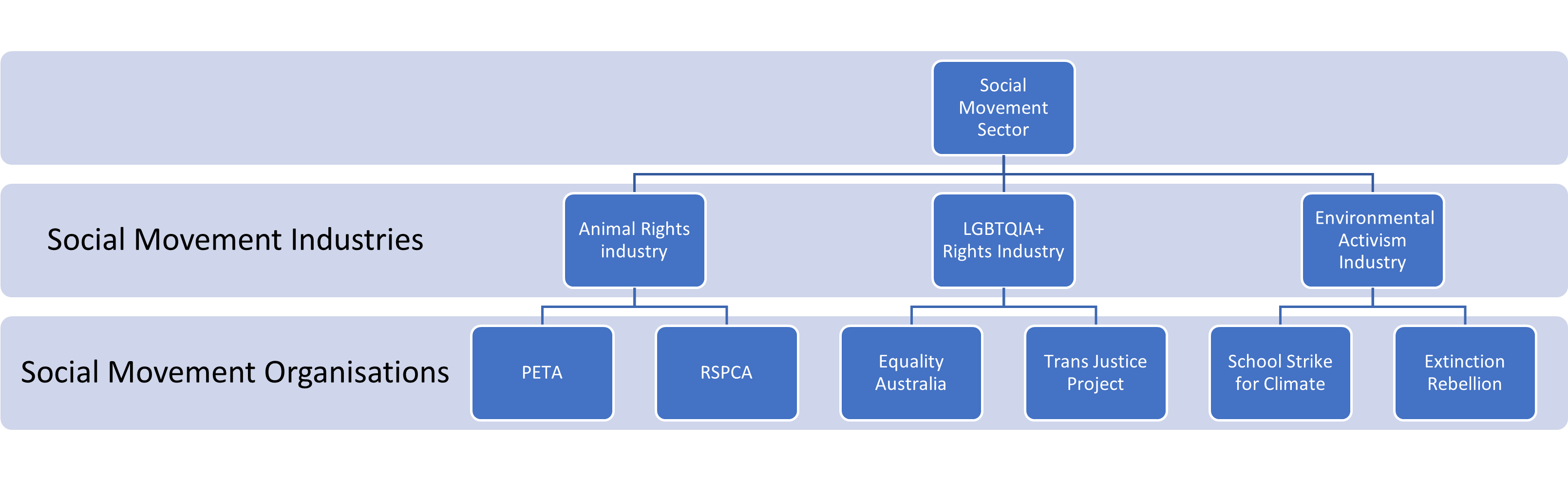

McCarthy and Zald (1977) conceptualise resource mobilisation theory as a way to explain a movement’s success in terms of its ability to acquire resources and mobilise individuals to achieve goals and take advantage of political opportunities. For example, People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA), a social movement organisation, is in competition with Greenpeace and the Animal Liberation Front, two other social movement organisations. Taken together, along with all other social movement organisations working on animal rights issues, these similar organisations constitute a social movement industry. Multiple social movement industries in a society, though they may have widely different constituencies and goals, constitute a society’s social movement sector. Every social movement organisation (a single social movement group) within the social movement sector is competing for your attention, your time, and your resources.

🛠️ Sociological Tool Kit: Collective Identity and WUNC

An important concept that social movement researchers use, especially (but not exclusively) in an RMT perspective, is collective identity. Collective identity is the shared sense of self that movements seek to instil in members. Sharing a movement identity can attract members to movements, and it keeps them involved by ensuring participants feel like they belong to the broader group.

Collective identity can be built on two types of identity. Embedded identities are those which are perceived outwardly by society, like race or gender, which are difficult for an individual to change. Detached identities are those which can be tried on, shed, or clung to depending on circumstances. For example, you can’t typically guess someone’s politics when they are in a grocery store unless they have chosen to wear clothing or accessories with an explicit political message.

Both kinds of identities are resources that social movements can seek to mobilise, and to make more salient (active and relevant, as opposed to a latent identity or one that isn’t central to one’s experience of the world).

A social movement with a strongly developed collective identity will have high rates of unity and belonging, encouraging ongoing participation in movement activities. That participation can then go on to create new (detached) identities—like “activist” or “environmentalist”.

Collective identity is a concept that is not just important to understand social movements, but lots of other groups in society. In your life, what groups do you belong to? What makes you feel like you belong?

Collective identity is closely tied to what sociologist Charles Tilly called WUNC—a movement’s worthiness, unity, numbers, and commitment. According to Tilly, these four things indicate whether or not a movement is important to society, and can influence the response of powerholders to that movement’s demands. The video below [6:33] contains a brief explanation of WUNC, and how it connects to collective identity—including the tension that some movements face between maintaining breadth.

Think of a social movement that has been in the news recently. What elements of that movement’s activities contribute to their display of WUNC?

Frame Analysis

The sudden emergence of social movements that have not had time to mobilise resources, or the failure of well-funded groups to achieve effective collective action, calls into question the emphasis on resource mobilisation as an adequate explanation for the formation of social movements. Over the past several decades, sociologists have developed the concept of frames to explain how individuals identify and understand social events and which norms they should follow in any given situation (Benford & Snow, 2000; Goffman, 1974; Snow et al., 1986). A frame is a way in which experience is organised conceptually. Imagine entering a restaurant. Your “frame” immediately provides you with a behaviour template. It probably does not occur to you to wear pyjamas to a fine dining establishment, throw food at other patrons, or spit your drink onto the table. However, eating food at a sleepover pizza party provides you with an entirely different frame. It might be perfectly acceptable to eat in your pyjamas, and maybe even throw popcorn at others or guzzle drinks from cans. Similarly, social movements must actively engage in realigning collective social frames so that the movements’ interests, ideas, values, and goals become congruent with those of potential members. The movements’ goals must make sense to people to draw new recruits into their organisations.

According to this theoretical perspective, successful social movements use three kinds of frames (Snow & Benford, 1988) to further their goals. The first type, diagnostic framing, states the social movement problem in a clear, easily understood way. When applying diagnostic frames, there are no shades of grey: instead, there is the belief that what “they” do is wrong and this is how “we” will fix it. This “us and them” mentality may build a stronger collective identity within a movement. Prognostic framing, the second type, offers a solution and states how it will be implemented. When looking at the issue of pollution as framed by the environmental movement, for example, prognostic frames would include direct legal sanctions and the enforcement of strict government regulations or the imposition of carbon taxes or cap-and-trade mechanisms to make environmental damage more costly. As you can see, there may be many competing prognostic frames even within social movements adhering to similar diagnostic frames. Finally, motivational framing is the call to action: what should you do once you agree with the diagnostic frame and believe in the prognostic frame? These frames are action-oriented. In the Aboriginal justice movement, a call to action might encourage you to join a blockade to protest coal mining on Aboriginal land or contact your local MP to express your viewpoint that Aboriginal land rights be honoured.

With so many similar diagnostic frames, some groups find it best to join together to maximise their impact. When social movements link their goals to the goals of other social movements and merge into a single group, a frame alignment process (Snow et al., 1986) occurs—an ongoing and intentional means of recruiting a diversity of participants to the movement. For example, Carroll and Ratner (1996) argue that using a social justice frame makes it possible for a diverse group of social movements—union movements, environmental movements, First Nations justice movements, LGBTQIA+ rights movements, anti-poverty movements, etc.—to form effective coalitions even if their specific goals do not typically align.

New Social Movement Theory

New social movement theory emerged in the 1970s to explain the proliferation of postindustrial, quality-of-life movements that are difficult to analyse using traditional social movement theories (Melucci, 1989). Rather than being based on the grievances of particular groups striving to influence political outcomes or redistribute material resources, new social movements like the peace and disarmament, environmental, and feminist movements focus on goals of autonomy, identity, self-realisation, and quality-of-life issues. The appeal of the new social movements tends to cut across traditional class, party politics, and socioeconomic affiliations to politicise aspects of everyday life traditionally seen as outside politics. Moreover, the movements themselves are more flexible, diverse, shifting, and informal in participation and membership than the older social movements, often preferring to adopt non-hierarchical modes of organisation and unconventional means of political engagement (such as direct action).

Melucci (1994) argues that the commonality that designates these diverse social movements as “new” is the way in which they respond to systematic encroachments on the lifeworld, the shared inter-subjective meanings and common understandings that form the backdrop of our daily existence and communication. The dimensions of existence that were formally considered private (e.g., the body, sexuality, interpersonal affective relations), subjective (e.g., desire, motivation, and cognitive or emotional processes), or common (e.g., nature, urban spaces, language, information, and communicational resources) are increasingly subject to social control, manipulation, commodification, and administration. However, as Melucci (1994) argues,

these are precisely the areas where individuals and groups lay claim to their autonomy, where they conduct their search for identity … and construct the meaning of what they are and what they do. (pp. 101-102)

Social Change

Collective behaviour and social movements are just two of the forces driving social change, which is the change in society created through social movements as well as external factors like environmental shifts or technological innovations.

Technology

Some would say that improving technology has made our lives easier. Imagine what your day would be like without the internet, the automobile, or electricity. Advances in medical technology allow otherwise infertile women to bear children, indirectly leading to an increase in population. Advances in agricultural technology have allowed us to genetically alter and patent food products, changing our environment in innumerable ways. From the way we educate children in the classroom to the way we grow the food we eat, technology has impacted all aspects of modern life.

Of course, there are drawbacks. The increasing gap between the technological haves and have-nots—sometimes called the digital divide—occurs both locally and globally. Further, there are added security risks: the loss of privacy, the risk of total system failure (like the Y2K panic at the turn of the millennium), and the added vulnerability created by technological dependence. Think about the technology that goes into keeping nuclear power plants running safely and securely. What happens if an earthquake or other disaster, as in the case of Japan’s Fukushima plant, causes the technology to malfunction?

Social Institutions

Each change in a single social institution leads to changes in all social institutions. For example, the industrialisation of society meant that there was no longer a need for large families to produce enough manual labour to run a farm. Further, new job opportunities were close to urban centres where living space was at a premium. The result is that the average family size shrunk significantly.

Population

Population composition is changing at every level of society. Births increase in one nation and decrease in another. Some families delay childbirth while others start bringing children into their fold early. Population changes can be due to external forces, like an epidemic, or shifts in other social institutions, as described above.

In Aotearoa New Zealand and Australia, we have an ageing population (StatsNZ, 2022, Australian Institute of Health & Welfare, 2021), which will in turn change the way many of our social institutions are organised. For example, there is an increased demand for elder care and assisted-living facilities, and growing awareness of elder abuse. There is concern about labour shortages and pension costs as baby boomers retire.

Globally, often the countries with the highest fertility rates are least able to absorb and attend to the needs of a growing population. Family planning is a large step in ensuring that families are not burdened with more children than they can care for. On a macro level, the increased population, particularly in the poorest parts of the globe, also leads to increased stress on the planet’s resources.

Environment

Humans are part of the environment, and we affect each other. As a result of climate change, we are seeing an increase in the number of people affected by natural disasters, and human interaction with the environment increases the impact of those disasters. Part of this is simply the numbers: the more people there are on the planet, the more likely it is that people will be impacted by a natural disaster. But it goes beyond that. As a population, we have brought water tables to dangerously low levels, built up fragile shorelines to increase development, and irrigated massive crop fields with water brought in from far away. These events have birthed social movements and are bringing about social change as the public becomes educated about these issues.

🔍 Look Closer: Dystopian Fictions?

People have long been interested in science fiction and space travel, and many of us are eager to see the invention of jet packs and flying cars. But part of this futuristic fiction trend is much darker and less optimistic. In 1932, when Aldous Huxley’s book, Brave New World, was published, there was a cultural trend toward seeing the future as golden and full of opportunity. In his novel, set in 2540, there is a frightening future. Since then, there has been an ongoing stream of dystopian novels, or books set in the future after some kind of apocalypse has occurred and when a totalitarian and restrictive government has taken over. Some of these books have a grim ending, but others contain the promise of hope.

What is it about contemporary times that makes looking forward so fearsome? Take the example of author Suzanne Collins’s hugely popular Hunger Games trilogy. The futuristic setting isn’t given a date, and the locale is Panem, a transformed version of North America with 12 districts ruled by a cruel and dictatorial capitol. The capitol punishes the districts for their long-ago attempt at rebellion by forcing an annual Hunger Games, where two children from each district are thrown into an arena full of hazards, where they must fight to the death. Connotations of gladiator games and video games come together in this world, where the government can kill people for their amusement, and the technological wonders never cease. From meals that appear at the touch of a button to mutated government-built creatures that track and kill, the future world of Hunger Games is a mix of modernisation fantasy and nightmare.

When thinking about modernisation theory and how it is viewed today by both functionalists and conflict theorists, it is interesting to look at this world of fiction that is so popular.

When you think of the future, do you view it as a wonderful place, full of opportunity? Or as a horrifying dictatorship sublimating the individual to the good of the state? Do you view modernisation as something to look forward to or something to avoid? And what factors have influenced your view?

Modernisation

Modernisation describes the processes that increase the amount of specialisation and differentiation of structure in societies resulting in the move from an undeveloped society to a developed, technologically driven society (Irwin, 1975). By this definition, the level of modernity within a society is judged by the sophistication of its technology, particularly as it relates to infrastructure, industry, and the like. However, it is important to note the inherent ethnocentric bias of such assessment. Why do we assume that those living in semi-peripheral and peripheral nations would find it so wonderful to become more like the core nations? Is modernisation always positive?

One contradiction of all kinds of technology is that they often promise time-saving benefits, but somehow fail to deliver. How many times have you ground your teeth in frustration at an internet site that refused to load or your phone connecting to Bluetooth when you don’t want it to? Despite time-saving devices such as dishwashers, washing machines and robot vacuum cleaners, the average time spent on housework is the same today as it was 50 years ago. Further, the internet has brought us information, but at a cost. The morass of information means that there is as much poor information available as trustworthy sources. And the dubious benefits of 24/7 email and immediate information have simply increased the amount of time employees are expected to be responsive and available. While once businesses had to travel at the speed of the postal system, today the immediacy of information transfer means there are no such breaks.

🧠 Learn More

A key campaign of labour union activism in recent years has been “the right to disconnect”. This is in response to increasing expectations that workers be always available by phone, email, or some other chat service. The government in France introduced legislation giving paid workers the right to disconnect when not at the office. Some industries in Australia and New Zealand have followed suit, but many have yet to do so. Will this become a broader social movement in the future?

In Summary

- Collective behaviour encompasses everything from crowds to social movements. Social movements are a particular form of non-routine collective action that attempts to create or resist political and social change. Social movements have had profound impacts on society as we know it.

- Social movements can seek to reform existing systems, replace them with something new, or sometimes create alternatives on a small, local scale. The things that social movements do are typically referred to as activism, and while many people commonly think of activism as meaning the same thing as protest, there are many other ways that a social movement can do activism.

- Sociologists use a variety of approaches to understand social movements, how they come about, and what their impacts might be. Resource mobilisation theory treats social movement participants as rational decision-makers; frame analysis explains how social movements articulate their issue to make it salient to new members; and New Social Movement theory considers the shift to postindustrial movements that are about more than simple redistribution of resources.

- Aside from social movements, other influences of social change include technology, the environment, population, and institutions.

References

Alexander, N., Petray, T., & McDowall, A. (2022). More learning, less activism: Narratives of childhood in Australian media representations of the School Strike for Climate. Australian Journal of Environmental Education, 38(1), 96-111. https://doi.org/doi:10.1017/aee.2021.28

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. (2021). Older Australians. https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/older-people/older-australians

Benford, R. & Snow, D. (2000). Framing processes and social movements: An overview and assessment. Annual Review of Sociology, 26, 611–639. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.soc.26.1.611

Blumer, H. (1969). Collective behavior. In A. M. Lee (Ed.), Principles of sociology (pp. 67–121). Barnes and Noble.

Bond, C. J., Whop, L. J., Singh, D., & Kajlich, H. (2020). “Now we say Black Lives Matter but … the fact of the matter is, we just Black matter to them”. The Medical Journal of Australia, 213(6), 248-251. https://doi.org/doi: 10.5694/mja2.50727

Corry, K. (2021). Flash mobs are back, baby. Vice. https://www.vice.com/en/article/v7eg3d/tiktok-brought-back-flash-mobs-natasha-bedingfield

Gladwell, M. (2010, October 4). Small change: Why the revolution will not be tweeted. Annals of Innovation. https://web.stanford.edu/class/comm1a/readings/gladwell-small-change.pdf

Goffman, E. (1974). Frame analysis: An essay on the organization of experience. Harvard University Press.

Gottbrath, L.-W. (2020, December 31). In 2020, the Black Lives Matter movement shook the world. Al Jazeera. https://www.aljazeera.com/features/2020/12/31/2020-the-year-black-lives-matter-shook-the-world

Irwin, P. (1975). An operational definition of societal modernization. Economic Development and Cultural Change, 23(4), 595–613.

Khondker, H. H. (2019). The impact of the Arab Spring on democracy and development in the MENA region. Sociology Compass, 13(9), e12726. https://doi.org/10.1111/soc4.12726

Le Bon, G. (1960). The crowd: A study of the popular mind. Viking Press. (Original work published 1895).

Lofland, J. (1993). Collective behavior: The elementary forms. In R. Curtis and B. Aguirre (Eds.), Collective behavior and social movements (pp. 70–75). Allyn and Bacon.

McCarthy, J. D. & Zald, M. N. (1977). Resource mobilization and social movements: A partial theory. American Journal of Sociology, 82(6), 1212–1241.

McPhail, C. (1991). The myth of the madding crowd. Aldine de Gruyter.

Melucci, A. (1989). Nomads of the present. Temple University Press.

Melucci, A. (1994). A strange kind of newness: What’s “new” in new social movements? In E. Larana, H. Johnston, & J. Gusfield (Eds.), New social movements (pp. 101-130). Temple University Press.

Petray, T., & Pendergrast, N. (2018). Challenging power and creating alternatives: Integrationist, anti-systemic and non-hegemonic approaches in Australian social movements. Journal of Sociology, 54(4), 665-679. https://doi.org/10.1177/1440783318756513

Silverstein, J. (2021, June 4). The global impact of George Floyd: How Black Lives Matter protests shaped movements around the world. CBS News. https://www.cbsnews.com/news/george-floyd-black-lives-matter-impact/

Smelser, N. J. (1963). Theory of collective behavior. Free Press.

StatsNZ. (2022, July 27). One million people aged 65+ by 2028. https://www.stats.govt.nz/news/one-million-people-aged-65-by-2028

Snow, D. A. & Benford. R. D. (1988). Ideology, frame resonance, and participant mobilization. International Social Movement Research, 1, 197–217.

Snow, D. E., Rochford, E. B. Jr., Worden, S. K. & Benford, R. D. (1986). Frame alignment processes, micromobilization, and movement participation. American Sociological Review, 51(4),464–481.

Tilly, C. (1978). From mobilization to revolution. McGraw Hill College.

Turner, R., & Killian, L. M. (1993). Collective behavior (4th ed.). Prentice Hall.

Wallerstein, I. (2002). Revolts against the system. New Left Review, 18, 29-39.

Non-institutionalised activity in which groups of people voluntarily engage.

A purposeful, organised group working toward a common goal.