Identity, Self and Culture in Classical and Contemporary Sociology

Nick Osbaldiston

The key goals and objectives of this chapter are to understand the following:

- the concepts of culture and identity in sociology

- foundational theories of culture and identity in classical sociological literature

- contemporary theories and sociological work in cultural sociology

- contemporary theories and sociological work in symbolic interactionism

- engage case studies/examples for deeper analysis.

Overview

As the previous chapter discussed, sociology has its roots in the turn towards science during the Enlightenment period and beyond in the 19th and 20th Centuries. As sociology started to expand throughout the Western world, so too did the different sites of social life that it sought to interpret and understand. While class and status remained important concepts for sociological examination, new ideas and concepts like ethnicity, gender, culture and identity grew in popularity. Importantly, these concepts allowed sociologists the opportunity to develop their own ‘style’ of sociology as we will see in this chapter. Like any discipline, sociology has many different approaches that privilege certain variables in the development of theory and research. In this chapter we will examine some of these in detail, however, there are far too many different fields of inquiry to cover here. Rather, we will focus on some of the major contributions to identity and culture in what follows. However, later in this textbook, you will find other important concepts such as politics, deviancy, technology, health, ethnicity, gender and sexuality, that all feed into the discussion around identity and culture.

Some Key Background Concepts and Ideas

Of the many different concepts you will learn about, culture is one of the most difficult and slippery to define and identify. Early meanings given to culture, especially out of anthropology, identified it as the system of morals, values, laws, customs, rites and rituals that underpin a community or society. Other anthropologists like Clifford Geertz (1973) defined culture as a whole system or way of life that includes not just morals and laws, but also artifacts, rituals, social interactions and layers of meaning invested in everyday life. Over time, however, and through sociological insights, culture has been interpreted by theorists through different conceptual lenses. Georg Simmel (1858–1918) who you will encounter below, considered culture to be a complex relationship between how people engage with the world symbolically, and how different facets of cultural life (such as art) created meaning for people’s lives.

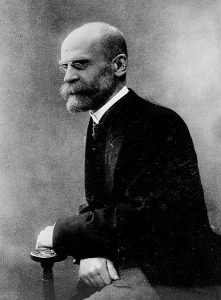

On the other hand, Emile Durkheim (1858-1917) and his students focused on culture being a great organiser of morals and values, as people come together in collective energy and unite around sacred things (see below). In recent years, cultural sociologists who follow the Durkheimian tradition use notions of collective values and the binary opposition between the sacred and the profane to understand all aspects of cultural life from war, political discourse, incivility, place and even sport.

Conversely, postmodernists like Jean Baudrillard (1983) contended that culture is effectively made up of signs and symbols, many of which become like language in everyday life. We use these signs and the cultural artefacts around us to demonstrate our identities or portray certain characteristics about ourselves in everyday life. Consider for instance the red rose. On its own, the rose is simply a flower, that has a certain texture and character to it. However, through cultural meaning, and shared understandings of what the red rose signifies, we understand it to be part of the ritual of love or romance. For Baudrillard (1983) though, our culture is filled with things that are representations or symbols of reality, but which have for him become ‘real’. A classic example would be a chicken nugget. Layers of symbolism have been advertised/marketed to us over the years presenting this as ‘real’ chicken. The reality is that the ingredients are a mixture of chicken and other additives. Furthermore, ‘chicken’ has bones, gristle, skin, and so on. Whereas the chicken nugget removes all of this. For Baudrillard (1983), much of our modern experience is now filtered through what he calls the simulacra of life – the fantasy, the unreal, the fake, now presented as real – so that it becomes ‘real’ to us.

American sociologist Anne Swidler (1986) utilised some of these approaches to develop a sociological understanding of culture as ‘meaning-making’. From her perspective, culture can be seen as a ‘toolkit’ where individuals use different ideas to unpack and make meaning out of different social situations in modern life. While individuals draw from cultural resources to assist them in understanding their lives, they also through their actions remake culture, creating social change. In other words, culture does not stay stagnant for Swidler (1986) and individuals are not simply governed by cultural norms, morals and values. Rather, individuals have agency, and will selectively use tools to assist them in meaning-making, in active ways. From this perspective, culture can be a driving force for social change (not always in positive directions) and as you will see, cultural sociologists like Jeffery Alexander and Philip Smith (2018), argue that culture is an independent variable, rather than a dependent one. For instance, Smith (2008) in his book on punishment argues that it is culture, not the nation-state and not disciplinary expertise, that pushes for change in punitive systems. This is contrary to such arguments from others such as Michel Foucault (1975).

Of course, culture can also denote the artifacts and activities that people participate in across society. This is where we can distinguish potentially between classes, or status (see prior chapter), where individuals from higher classes might participate in ‘high culture’ whereas others in ‘low culture’. Critical theorists (and Marxists) Adorno and Horkheimer (1997) in their examination of the Culture Industry critique cultural life by arguing that our obsession with things (material objects and commodities) take us away from authentic matters such as our human condition or social relations (Woodward, 2007). In particular, the culture industries no longer serve to produce social good or challenge status quo thinking. Rather, as they argue, it serves only capitalism – and profit. Furthermore, the cultural industries distract people away from understanding and challenging the exploited nature of capitalism. For these theorists, and others who formed what is known as the Frankfurt School, culture industries, along with consumerism, serve only to uphold capitalism and repress revolutionary potential.

As alluded to above, the link between our culture and who we are as ‘selves’ is important in sociological analysis. Instead of discussing the ‘self’, which philosophers tend to focus on, sociologists often use the term identity. Identity refers in principle to the complex make-up of who we and others think we are. Identity emerges from our socialisation throughout our youth, but also in our relations to culture, context, other people and of course, biological, psychological, and genetic make-up (though sociologists have avoided these last three matters – see below). The difficulty we face when discussing identities is to balance issues like genetics, with the broader environmental contexts that impact who we are as people. This is difficult to assess at times, but sociologists try to explore the way social interaction occurs, and how this impacts our understanding of who we are, and the roles we play in everyday life.

Most sociological theorists are interested in identities, but a group of American scholars known as the symbolic interactionists that included significant names such as George Herbert Mead (1963-1931), Herbert Blumer (1900-1987), Erving Goffman (1922-1982), Harold Garfinkle (1917-2011), Robert Park (1864-1944) and pioneer female criminologist Ruth Shonie Cavan (1896-1993). Fundamental to the development of this approach was Mead who argued that our experiences as individuals living in everyday life are essentially social. In other words, every day, you and I engage with others, humans and non-humans, which have symbolic meaning to us. We communicate with each other, share interactions with one another, and adopt different roles in each context because of this interaction we share. We will explore this in more detail below in the chapter.

Of course, identities are made up of different layers of sociological constructs from gender (see chapter on gender), ethnicities (see chapter on ethnicity), class (see chapter on class) and ideologies (see chapter on political sociology). In this contemporary age where social media is so prevalent, identities are challenged daily by digital data and our interactions with one another online (see chapter on digital sociology). Generally, sociologists tend to agree that modern life has become less governed and structured by traditional norms and values, as well as institutions. British sociologist Anthony Giddens (1991) for instance argues in his seminal work Modernity and Self-Identity, that identities are freer than ever before. We have become, for Giddens (1991), critical of past traditional institutional norms, such as marriage, and subsequently make our own lifestyle choices accordingly. The choices we make impact who we are, and for Giddens (1991), individuals in modernity now create their life biographies or narratives via them. While we are freer than ever to make these decisions, they come also with risks. While in the past in traditional premodern societies, your choices such as occupation were more or less made for you, in late modern societies your choices are open, but also laden with risks of failure. Thus, people become reflexive, examining carefully the choices available to them, weighing up options, and importantly, consulting widely with different expertise before making a choice (see also Beck, 1992; Bauman, 2005). For someone like Giddens (1991), but also Bauman (2005) and Beck (1992), we have no option but to make lifestyle choices now and face the consequences of our choices without the support of traditional institutions and the state.

There is only so much space that we can dedicate to all these ideas. At the end of the chapter, there is a list of recommended readings that may prove useful if you want to know more about concepts and ideas not covered below. However, what follows is a curation of ideas/theories/concepts on the topics of culture and identity. We focus here specifically on the development of the sub-disciplinary area of cultural sociology through Emile Durkheim’s initial work on religion, the more bleak approaches to culture via Georg Simmel and Max Weber, and the symbolic interactionist approach to identity via social interaction. As noted already, most of the chapters that follow this delve into other sociological concerns of ‘identity’ and ‘culture’, including questions of gender, race/ethnicity, global politics, deviancy and crime, and our ever-growing digital lives.

Cultural Sociology: Durkheim and Beyond

One of the most pivotal thinkers you will hear about in most sociology textbooks is that of the French sociologist Emile Durkheim (1858-1917). Durkheim is considered to be the father of French sociology and also has been labelled as one of the most important figureheads in the development of the discipline generally. Often, the Frenchman is attributed to the school of thought known as ‘functionalism‘. However, Durkheim had a significant impact on the development of a sociology that is attuned to the question of culture, and the influence that it has on social change or cohesion.

Influenced by a number of thinkers including Auguste Comte, Durkheim initially started his sociology by exploring and examining society from a macro perspective (Turner et al., 2007, p. 279). This is evident especially in the widely cited (and taught!) debates he had through The Division of Labour in Society (1893/1964) where Durkheim laid out his concern for the transformation of the organisation of the social. In particular, Durkheim (1893/2013) was worried about how integrated individuals would feel in a society that was shifting dramatically into diversified roles and expectations. In short, Durkheim (1893/2013) emphasised the need to understand how to keep people socially integrated, in an increasingly individualised society. As Turner et al. (2007) suggest, it is this concern that underpinned Durkheim’s work and influenced others right up until today.

Three major points need to be made here to provide the foundation for Durkheim’s later and more influential work on religion in relation to culture. Firstly, Durkheim (1893/2013) emphasised the importance of collective values, ideas and norms in his work, labelling this the ‘collective consciouness or ‘collective representations’. We can see this, in his words, as “the totality of beliefs and sentiments common to the average members of a society forms a determinate system with a life of its own. It can be termed the collective or common consciousness” (Durkheim, 1893/2013, p. 63). We might prefer here to term this ‘culture’ – as culture holds all of our collective values, ideas, norms and expectations of which we ascribe to. As individuals, we both add to this through our actions, but also are constrained by it. For instance, consider an everyday life norm such as civility and good manners. There is a cultural expectation placed upon us to say ‘please’ and ‘thank you’, while we also hold others to account in this regard as well. This is the collective consciousness, for Durkheim (1893/2013), in action.

Secondly, Durkheim (1893/2013) argued that modernity led to the transition of society from what he called mechanical to organic social solidarity. Premodern societies were often characterised by their small community/communal setting, often bound together by kinship ties, well-defined roles, and importantly, socially defined by strong collective conscience – what he terms mechanical solidarity. Importantly, societies like these are often deeply religious, with a collective commitment to sacred values and collective worship. Conversely, contemporary societies, such as big cities that expanded greatly through early modernity, were characterised by large-scale populations, bound together by diverse and impersonal ties (especially through exchange in a capitalist market), and weaker collective consciousnesses – what he terms organic solidarity. Unlike mechanical solidarity, societies that evolve in this state tend to be secular or hold to religions that are largely individualised (in other words, emphasise individual worship, rather than collective worship).

Thirdly, Durkheim (1893/2013) envisioned the transition into organic solidarity as somewhat inevitable for Western societies like France. This raised concerns for Durkheim that individuals would fall into ‘anomie’. This refers to the transition of society to one that emphasises the individual, drawing them away from the collective, towards their own interests, their own values, their own ambitions, and so on (Lukes, 1973). This was a concern for Durkheim (1893/2013) for individuals would become less integrated, deeply isolated, and exposed to the crushing nature of capitalism and the industrialisation of life. Furthermore, and somewhat like Marx and Engels, Durkheim (1893/2013) thought that it would inevitably lead to social unrest and potential revolutions. Thus, it could be argued that Durkheim’s (1893/2013) fundamental concern was how modernity was turning people into individuals who felt no connection to their society, or culture.

This anxiety towards the future of modern society led Durkheim (1912/1995) to analyse religions across societies considered premodern in his work entitled The Elementary Forms of Religious Life. Using ‘totemic’ cultures from some of the Aboriginal nations of Australia, Durkheim (1912/1995) attempted to understand what were the building blocks of religious/spiritual life, in places that still represented mechanical solidarity. It is important to note, that the Frenchman never undertook ethnographic work in any of his work. Rather in this work, Durkheim (1912/1995) relied on the ethnographies of others like Baldwin Spencer and Francis Gillen’s The Native tribes of Central Australia (1899). Subsequently, there are errors that we are aware of now in contemporary society including the criticism that trying to find the roots of religion in Indigenous Australians was nonsensical. For Geertz (1973), this was Durkheim trying to impose his already established heuristic onto a people who the theory did not really fit. Nevertheless, Durkheim’s (1912/1995) theory has had a significant impact on both anthropology and sociology since publication.

For Durkheim (1912/1995) religion is fundamentally based on the sacred, and the opposition this has to the profane. The world for him is divided between these two poles – the sacred, being those things, ideas or beings which society attributes “virtues and powers” to, and the profane, being the everyday world around which the sacred requires protection from (Durkheim, 1912/1995, p. 34). The sacred can be anything for Durkheim (1912/1995, p. 35), “a rock, a tree, a spring, a pebble, a piece of wood, a house, in a word anything”, even people. What is important for him is less the item of interest, but rather the power the item has to a community or society because of the collective valuation they place on it. These sacred things/beings, importantly for him, must be protected from the defilement of everyday life, otherwise it would lose that value. Following this dichotomy of the sacred and profane, Durkheim (1912/1995, p. 44) arrived at the conclusion that religion, “is a unified system of beliefs and practices relative to sacred things, that is to say, thing set apart and forbidden – beliefs and practices which unite into a one single moral community called a Church, and all those who adhere to them”. In all religions, you will find the sacred for him – around which is organised worship, rituals, and rites.

Important to Durkheim (1912/1995) is less the sacred objects themselves, and more the interactions that occur around them. The organisation of people, coming together in a collective revelry, ritualistic worship and even a “state of exaltation” (Durkheim, 1912/1995, p. 220). He saw religion as enacting a type of force that enabled people to feel that they belonged to something larger than themselves, which would ultimately achieve two main points. One it would allow people to feel connected and integrated into a wider community whole, and second, it would provide a place for the reinforcing of commitment to the morals and values of the collective. In short, religion allowed people to feel like they belonged to larger than themselves – and then recommit to a wider culture.

For Durkheim (1912/1995), the building blocks of religion might hold the secret to overcoming the ills of modernity. Religion for him would not survive in a secular modernity – much like what Marx and Engels argued. However, instead a new ‘sacred’ might be created or appear that allows similar collective membership and belonging. He saw, importantly, that it might well be the state and nation that take the place of religion – creating sacredness organised around what it means to belong to the country/culture. Consider the national flags that adorn our public places, or the flags that represent our culture/ethnicity. These in particular provide a sense of identity, along with organising us into collectives and at times, are sacred in that we perform rituals under them such as singing the national anthem. In some cases, it is a significantly immoral thing to desecrate the flag, even to the point of imprisonment in some nation-states. Or consider the sacred power of the emblem for a sports team. Importantly here, the crest of your favourite sport’s team identifies you as one of the fans, but also separates you from other fans of other clubs. This is then intimately tied to your identity.

Durkheim’s students continued to work on the sacred alongside him and well after his death in 1917, focusing on the nature of these imaginative templates in cultural life. For instance, Henri Hubert (1905/1999), researched the nature of sacred times cut off in the calendar of everyday life such as Christmas or other religious festivals that served to bring people together in collectives. Durkheim’s own nephew Marcel Mauss (1906/2013) also examined the nature of seasons for Inuit people showing that wintertime in particular was full of certain intense religiosity and important taboos. He also is famous for his work on the nature of gift-giving, showing that the practice of reciprocal gift-giving as a form of cultural exchange is not limited to Western societies (Mauss, 1925/1990) which has had a tremendous impact on anthropology. Robert Hertz (1909/2009) examined how in rituals, the right hand would often be the one used, whereas the left would be considered the evil, or profane. Hertz (1909/2013) also emphasised the dual nature of the sacred, being both something that can inspire and create collective emotional energy, but also horrify and distress creating tension and anxiety. Anthropologist Mary Douglas’ (1966/2003) masterpiece Purity and Danger follows a similar trend in the analysis of society broadly through the twin poles of purity and pollution. For her, tracing the meanings of dirt to different societies, what is considered clean and unclean is a matter of cultural context – and laws/taboos/norms around these were cultural forms of boundaries. What is right, what is wrong, what is clean, what is unclean – are all the result of wider cultural ideas and values contextualised by place and time.

Since Durkheim’s (1912/1995) engagement with the sacred as a concept, there has been significant work across the social sciences grappling with how it operates in modern culture. Riley (2010) illustrates in his work that the intellectual habitus built into modern intellectual life, especially in France, of researching the sacred, the profane, rituals and taboos, led major theoretical works from George Bataille, Jean Baudrillard, and even Michel Foucault. However, it is within cultural sociology today that we see the impact of Durkheim (1912/1995) more acutely.

There is a division between those who study culture in sociology and those who are cultural sociologists. Sociologists of culture examine aspects of our modern lives that are shaped, produced or altered as a result of outside forces. For instance, Max Weber’s rationalisation thesis argued that modern cultural practices, such as art or music, were being heavily routinised and disenchanted as rules or norms on how to do it appear, to be efficient, but also effective in profit making. Cultural sociologists on the other hand argue that society, and the institutions/structures within them, are at their core cultural. The ‘new’ Durkheimians such as Jeffrey Alexander and Philip Smith (2018) construct a program of cultural sociology that envisions cultural codes, values, ideals, and imaginative life, as a collective force on structures in our society. In other words, culture is independent, it enables us to make meaning of the world, experience it, and at times change it. Conducting analysis on culture requires unpacking the imaginative templates, like the sacred and the profane, impure or pure, good and evil, that culture uses to make sense of the world around it, but also at times govern or change it.

Several scholars have emerged in sociology down here in the south organised under this umbrella. For instance, Brad West (2022) unpacks the nature of Australian and New Zealand tourism to Gallipoli (the site of one of the first conflicts in World War One for Australian and New Zealand troops – ANZACS) as a form of cultural pilgrimage embedded with deep meaning. He argues that these trips are symbolic, and when amongst the sites of war at the place of Gallipoli, individuals are collectively engaging in the sacred through ritual. Osbaldiston and Petray (2011) also argue that these are places where people experience both the positive affirmation of the sacred, but also the negative horrors of it when confronted with symbols of death. Others such as Ian Woodward (2007) spend time locating the cultural force that we give to objects and the cultures that form around them such as we can see in vinyl record collecting today (Bartmanski & Woodward, 2018). Margaret Gibson (2008) further examines the ways objects of the dead, surround us personally and are invested with significant value, and power, long after people have passed away.

Important to cultural sociology then is a collective narrative or theme, that underlines our cultures which produces agreement on certain things, but also governs behaviour. For instance, Philip Smith (1999) shows in his paper on place, how cultural framing of certain places can impact how one behaves when in that area. In some cases, places might have a sacred quality to them, which encourages a reverent tone, or a quiet solemn approach.

For instance, walking to the Pool of Reflection in the War Memorial in Canberra, an individual must walk past the names of fallen men and women in combat. The cultural narrative here is one of reverence for those passed. What do you think would happen to someone who violated these norms? For Smith (1999) though, there are other places too – ones that horrify and disgust us creating rituals of destruction or avoidance. There are also places that encourage the unshackling of restraints where morals are loosened – such as a casino. Here, places are defined by ‘letting loose’ – such as Las Vegas. As you can see, however, cultural sociology today tends to examine how cultural templates or imaginations such as the sacred, exist and influence society today.

The Rationalisation, Disenchantment, and Tragedy of Modern Culture?

One of the figureheads of sociology that you will hear mentioned a lot in this text and in others is that of the German sociologist Max Weber (1864-1920). Best known for his approach to sociology through the ‘interpretivist’ tradition (see chapter on methods), Weber’s sociology was founded on an approach that tried to examine society from an individual standpoint. In particular, unlike Durkheim and others, Weber’s approach to sociology was one which rejected the positivist approaches to research. Instead, he argued that understanding modern life could only be achieved by interpreting individual social actions. The individual becomes both an actor but also a reflection of the society that they live within.

Aside from his methodological positions, Weber (1919/2012) also produced some of the most important sociological theories of modernity, including his concept of rationalisation and disenchantment. Put simply, Weber argued that in premodern life, before the enlightenment period and especially before the scientific advancement of knowledge, societies or communities acted in accordance to myth, religious or spiritual information. Life in this state, for him, presented to people a mystical reason for different events, but also provided life with a certain unknown quality with attribution for it given to the gods or divine above. For instance, if a natural disaster struck, this was the work of the gods in divine punishment or discipline of their people. As such, life had a mystical quality that could not be weighed, measured or understood. God’s ways are mysterious, as the biblical saying goes.

For Weber (1919/2012) the period of Enlightenment advanced scientific knowledge significantly, creating rational knowledge about the world that we live in. Things could be measured, understood, and unpacked scientifically – also known as rationalisation and disenchantment for him. From his perspective, science is like the metaphor of Pandora’s box. Once opened, the world as mysterious, unknown and mythical would never again be recaptured, and life would increasingly be dominated by the rational knowledges. In his famed lecture Science as a vocation, he argues the following:

It is the fate of our age – with the rationalisation, the intellectualisation and, above all, the disenchantment peculiar to it – that precisely the ultimate and most sublime values have withdrawn from the public sphere, either in the realm of mystical life in a world beyond the real one or into the fraternity of personal relations between individuals. (Weber, 1919/2012, p. 352)

Modernity, and the modern push for rational ways of understanding life, meant that not just the sciences, but all spheres of modern life would become rationalised eventually. Weber (1905/2002, p. 13) described the culture that developed as a result as a hard “immutable shell” in which individuals are “obliged to live”. Everything is subjected to rationalisation. Life for him has become cold, calculating, intellectualised and reasoned. Not only does this extend to the most obvious places, such as the economic world where goals can be achieved through heavy statistical calculation, but also for Weber across cultural life, the aesthetic, the political and even the romantic. The point for him is that in each area of culture, we develop a strong understanding of how to do this most effectively, and efficiently, to achieve goals. Consider dating in the contemporary age as an example. Dating you could argue once was achieved through luck, opportunity, or chance. Love was conceived of, almost as mystical. However, dating services and apps, via scientifically measured and constructed algorithms, attempt through probability to match people with those who, statistically speaking, will lead to a successful relationship. What does this do to romance? For Weber, it reduces it rationally, removing the irrational from the equation perhaps.

For Weber (1919/2012, p. 348) though, the more widespread and deeply embedded this process of disenchantment happens, the more likely it is that people will also seek out the irrational. As Barbara Adam (2009, p. 11) describes it, rationalisation means we yearn for “spiritual fulfilment, sublime values, and in the most general sense, all that escapes the iron grip of rationality in the social world”. It also meant for Weber an increase in an appreciation for those leaders who might buck the ‘status quo’ through charisma in modern politics (see political sociology chapter). In short, as life grows ever more calculative, and in some respects predictable, individuals will seek out escape within cultural life. The interesting question for us might be whether that does exist in our contemporary culture today? What areas of cultural life do you see us seeking out for the ‘irrational’ or the ‘sublime’?

American sociologist George Ritzer (2010; 2011) throughout his career adapts Weber’s thinking through his analysis of modern society. Initially in his book The McDonaldisation of Society, Ritzer (2011) argues that our institutions, including our cultural life, are standardised, predictable, efficient, and controlled. Ritzer (2011) bases his theory on the organisation and production cycles found in McDonalds. He contends that this giant food chain operates on the principles of rationality that Weber described. Everything is standardised in McDonalds, managed and controlled with precision, to produce food in the most efficient, quick, and cost-efficient manner. Additionally, the fast-food chain grew successfully across America, and the world, creating a standardised experience for all. In short, you can enter any McDonalds and expect some of the same food on the menu. Ritzer (2011) argues that this reflects cultural life generally as well. Art, literature, movies, sport, leisure and other forms of our culture are heavily standardised, and predictable, based on efficiency and cost-effectiveness. Above all, the corporations and businesses that operate within our cultural life know what ‘sells’, and will produce commodities, artifacts and productions based on this knowledge. We might ask if Ritzer (2011) is right – does our cultural life seem to follow the same model of a McDonalds? Does our cultural life seem overly predictable and standardised? Consider movies for instance. Are they mostly predictable today?

Ritzer (2010) also examines our attempt to re-enchant our culture through the spectacle of consumption. Using examples like Las Vegas, the shopping centre, sports stadiums, universities, and tourist locations, Ritzer (2010) argues that the owners and businesses in these places create magical worlds and spectacles to construct what he calls “cathedrals of consumption”. Take for example the shopping centre, which is fundamentally a place for consumption, or the buying of goods and services. Ritzer (2010) contends that these are now quasi-religious places, where we gather not just to shop, but also to eat food, watch movies, enjoy entertainment, and have fun. Also, these places create landscapes within to blur boundaries between the real and the unreal – for instance the building of mini eco-systems including trees and ponds (coupled with fish!) inside. The shopping centre is therefore a place of experience, not just to consumption. For Ritzer (2010) this is just one example where consumerism attempts to re-enchant life with the spectacle. However, the spectacle is also only designed to do one thing, to keep you inside the walls of the place, and to keep you consuming.

Not all agree with Weber and others like him, however. Social theorist Jane Bennett (2001) argues in her work The Enchantment of Modern Life that there is still much that is wonderful in a world that has been made ‘known’ by science. She argues that modern life is full of enchantment and the unknown – arguing especially that in the sciences, wonder on how organisms work, even the most mundane things, is deeply meaningful, enlightening and enchanting. This also includes of course, some of the bigger questions that we have around the nature of our universe, and the sublime feelings that come from knowledge of how large and expansive it is. Furthermore, Bennett (2001) contends that to be ethical in a modern world, we need these experiences of enchantment in order to create empathy, generosity and produce deeper meaning in our lives. What do you think of her argument and that of Weber’s? Is there wonder and enchantment still in our cultural life? Or is the world increasingly predictable, rational, efficient, and calculable?

Another name you will hear often in sociology is that of the German sociologist and contemporary of Weber, Georg Simmel (1858-1918). Simmel was much less recognised than his peers however, mostly due to the essayistic style of his work and metaphysical approach to sociology which covered everything from the bridge, the door, the meal, the adventure through to larger deliberations on economic life in his book The Philosophy of Money. However, Simmel’s work on culture follows a similar trajectory as Weber in that he foresaw concerns within the direction of modernity. In particular, Simmel (1991) argued that culture can be divided into two areas, objective and subjective. Objective culture, represented as the cultural forms, institutions and artifacts in our society generally – for instance, the technologies, arts, religions, government, norms and so on. Simmel (1991) argued that we use these as obligatory points through which we cultivate ourselves – and make sense of our place in the world. Take for instance literature or the arts, used, he would argue, to reflect on who we are as individuals, but also our place within the wider culture. For Simmel (1991), objective culture like this is important for a society to grow and develop – but also give a sense of self and connection to individuals – which he describes as our subjective culture.

The ‘tragedy’ of modern life for Simmel (1991) however is that modern objective culture has grown too large, and has become separated from the needs of subjective culture (us). He argued that objective culture has become “independent” imposing its “content and pace of development on individuals, regardless of or even contrary to the demands that these individuals ought to make for the sake of their own improvement, that is the acquisition of culture” (Simmel, 1991, p. 91). The objective cultural world has developed its own logic, and reason for being, independent of the need to produce meaning or cultivate individuals in society. However, these industries demand of society that they know of them, engage with them and consume them. In other words, objective culture has dominated cultural life to the point that these things, institutions, and industries dictate individuals on how to live (Pyyhtinen, 2018, p. 119). As Pyyhtinen (2018) illustrates, consider how much fashion and other ‘stylistic’ industries dictate how we consume but also dress ourselves and thus create our identities. Or consider how movies or music have dominated our cultural lives, no longer serving to increase understanding, but rather simply existing to make money. For Simmel (1991), the tragedy in all this is that we lose our place for cultivation, and become overwhelmed by objective culture. This includes not simply culture industries like movies, but also bureaucracies, governments, institutions, and so on.

Later in his life, Simmel (2010) turned towards trying to understand life generally in relation to culture and how individuals develop their ethics or ‘ought’ on how to live. Simmel (2010) developed a complicated approach to this. However, we simplify it as a constant negotiation between our life experiences and our personal reflections. In other words, the world that we inhabit and the relations we have with others (throughout our lives), create the foundation for what we feel life ‘ought’ to be (Simmel, 2010). Subsequently, there is no overarching objective ‘truth’ that emanates from culture from above (contrary to Durkheim), rather our own personal ethics on, for instance, the ‘good life’, emerges through a constant negotiation, reflection and experience of everyday life with others. Thus, our understanding of what we ‘ought’ to be thinking, feeling and doing is in constant flux – always changing with our relationships around us, impacting on our choices and how we understand and make meaning. This is what we call in sociology ‘relational’, which effectively means that much of our social, cultural and individual lives is shaped by the experiences and relations we have with others. This approach of Simmel’s in some ways is the foundation of another group of theorists called the symbolic interactionists.

🔍 Look Closer: Simmel and city life

Following the theme of the overtaking of objective culture over subjective life for Simmel, is the famous essay he wrote in 1903 entitled ‘The Metropolis and Mental Life’. In this highly insightful essay, Simmel (1991) argues the following:

- In large cities, people become socially reserved, not wanting to talk to others and keeping largely to themselves

- People also become ‘blase’, or dulled, to the world around them, as the cities assault their senses with lights, sounds and smells.

- The city is the home of capitalism, and as such is a vibrant, large commercial hub, creating a mammoth amount of cultural artifacts – this overwhelms the individual as stated above.

- The city allows for people to hide away, and not be too exposed – one can become part of the crowd by dressing similarly and not standing out.

- However, unlike the country or rural places, city folk do not have as much connection to one another. He infamously argued that people in the city do not even know their neighbours’ faces, let alone their names.

- However, unlike the country, people in the cities do not have their everyday lives constantly monitored or gossiped about, unlike those in smaller places.

What do you think? Does the city overwhelm us and make us socially reserved and blasé? What differences, if any, do you see between culture in the city versus culture in regional or rural towns in Australia or New Zealand?

Symbolic Interactionism – the Self and Beyond

Hopefully, by now you can see that someone like Durkheim imagines culture as a force that gives meaning but also constrains from the top down and can be studied accordingly, whereas Weber and Simmel saw the world as far too complicated for that, arguing that culture can be seen in individuals, and how they negotiate and reflect on the world around them. This division can be seen in the methodology of positivism vs interpretivism which you will encounter in the next chapter. However, the idea that society and culture are built from the ground up (not the top down), is the foundation of the works of the symbolic interactionists. In particular, how we come to understand who we are as people, and our identities, is for this group of scholars a constant ongoing development through our interaction with groups, people, ideas and thoughts. In what follows we unpack this idea further, focusing instead on the notion of identity and how we all cobble this together in the contemporary world.

The founder of symbolic interactionism is generally considered to be the American philosopher and sociologist George Herbert Mead (1863-1931) who emerged from a line of thinkers known as ‘pragmatists’ (along with scholars like John Dewey (1859-1952), Charles Peirce (1839-1914) and Jane Addams (1860-1935). Fundamental to pragmatics is the contention that individuals encounter symbols, language, people and ideas in everyday life, which they engage with, reflect on, and think through, that has influence on their actions/ideas. Furthermore, pragmatists consider that humans do have agency in their relationship to surrounds (including the economy contrary to Marx), and can influence the direction of society generally. Jane Addams in particular engaged positively with this idea, arguing for social change through the direct action of people into democratic processes – attempting to combine theory into action. She became, as a result, instrumental in the women’s suffrage movement in the early 1900s. For others like Peirce (cited in Turner et al., 2007, p. 322), pragmatism required interpretations on how people encounter language, symbols and relations that caused them to “self-control”. In any account, the point of this style of thinking is to study on-the-ground impacts, consider that humans can create change, and accept that people are also rational human beings who will interpret according to logic and reason.

Some of the most important contributions of Mead (1934/1972) come in his book Mind, Self and Society in the areas of the mind, symbols and role-taking. Firstly, the mind for Mead (1934/1972) exists only due to the interaction that we have in our everyday lives and within different contexts. He argues that “we must regard mind, then, arising and developing within the social process, within the empirical matrix of social interactions”, where the individual cannot be conceived of as, “in isolation from other individuals” (Mead, 1934/1972, p. 133). In other words, the mind does not exist alone, it comes to being through social relations we have. While the brain of course exists in isolation biologically, the behaviours we learn, experience, interpret and produce meaning through, happen because of our relations with others.

These, however, are importantly not simply language. We arrange our social relations through a range of verbal and non-verbal communication including gestures, symbols, certain words, sounds and the responses of those who are receiving them. Unlike animals who all gesture to one another to display certain emotions (for instance consider a cat growling and hissing to another cat), humans for Mead (1934/1972) are more complex and encode shared understanding of symbols in word and gesture. This can only exist for him based on role-taking. A person receiving the symbolic gesture can understand it only because they are able to place themselves (even unconsciously) in the role of the other person. For example, if a lecturer comes to class and slams his books onto the table, shaking his head and peering at his students with narrowed eyes and a frown, it does not require explaining to the students how he is feeling. This is not an automated response though for the students encoded into their biology. Rather, this exists for Mead (1934/1972) only because we share an understanding culturally of what that gesture means, and students understand the lecturer’s role, and can attribute actions based on that role. Symbolically, how we act and react to others is a form of culture, that exists in the everyday where we share meaning and understanding of each other, even strangers.

Role-taking, and understanding, feeds directly into our understanding of our ‘selves’ or identity for Mead (1934/1972). In particular, there are two aspects of the self that needs to be understood here – firstly the ‘me’ which is your understanding and relation of yourself in different roles (eg. student/teacher above) and secondly ‘I’ which is your own understanding of who you are as a person. This latter part of your self emerges in accordance to the relations you have with other people. This includes the way they respond to your behaviour and what your reactions are to them. For instance, you might come to class and start to behave jokingly in front of other students, causing them to laugh, and eventually come to know you as ‘funny’. This identity that they have is cast upon you, changing their behaviour, but also causing you to perhaps adopt the role of the ‘funny’ person from hereon. Your actions and the positive support of them from the others (such as laughing at your jokes), will only enhance your identity further. For Mead (1934/1972) this is not something you just acquire overnight however. Throughout your life, your self-concept is developed within the initial stages of childhood where you learn roles and notions of the self, and through to later life as a child and teenager where you learn more complex ideas of who you are. This then extends throughout your life as you constantly shape and reshape your identity based on new roles and new responses to behaviour from others.

Mead’s (1934/1972) influence extended to the scholarship of his student Herbert Blumer (1900-1987). Blumer (1969) developed Mead’s work further into a school of thought, symbolic interactionism, constructing methodological and theoretical premises to this form of sociology. There are effectively three of these as follows;

- Humans act/react on the basis of meanings which they give to different objects, events or people. In other words, people do not simply act in some form of biological determinism. We are social creatures, and our actions are not simply automated through some form of unconscious programming (like animals).

- Meaning is constructed or derived from the interaction that individuals have with others. In other words, meaning is not fixed forever, but changes accordingly through action and reaction over time. Norms of behaviour are therefore, never ‘normal’ or fixed, but rather shaped according to the actions and reactions of people in interaction with one another.

- Meanings are understood, and modified, through an interpretive process undertaken by the individual with agency. People do not simply make sense of the world around them through norms created for them, but negotiate these according to different ideas and values. People are indeed creative, and not simply conditioned to act certain ways by society or culture (as Durkheim might contest). We reflect, ponder, engage, reject and question meaning all the time. These actions (as per premise 2) impact how we see the world, and can create social change.

We can simplify this for you with an example. Imagine you are queuing up with your friend to get some food at a cafe. You line up behind others ahead of you until someone walks directly up to the cash register and starts to order food. The other people in the queue get annoyed and whisper to themselves, but no one says anything. Your friend turns to you and says something derogatory about the person who jumped ahead. You nod in agreement. What sorts of symbolic norms are being shared amongst the people in the queue? What sorts of gestures do they have in common in shared understanding? How would you react? Can you think of any other shared interactions like this where the premises of Blumer (1969) can be used to analyse them?

Contrary to mainstream sociology of his day, but also of the past sociologists like Durkheim, Blumer (1969) saw sociology’s main task is to understand that society, culture and the self, are not simply fixed. Rather, through an ongoing process of interaction, interpretation and reflection, these things are constantly in flux. People are always interacting, creating meaning, sharing that meaning, and at times challenging those meanings creating new ideas, values and norms. The self, or your identity, is never completed and is always developing as you are introduced to new roles, new situations and as such new meanings of who you are as a person. We are not simply products of culture, but rather, agents with agency with creative potential – but acting with others in a constantly changing culture.

Perhaps one of the more common names you will hear associated with this school of thought is that of Erving Goffman (1922-1982). Importantly, Goffman (1959/2002) coined the term ‘dramaturgical sociology’ in his now well-cited book The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life, which, to a degree, reflects the great metaphor from Shakespeare ‘all the world is a theatre’. Goffman, like the other symbolic interactionists, focused his work on the deeper underlying meaning that exists in life at the everyday level. While the world is not a theatre in the explicit sense for him, our everyday lives and interactions are far more like a play than what we might admit. As such, your notion of who you are, your identity, emerges from the roles you play in life, and the ‘performances’ which you give in public life (and private perhaps too).

Important for Goffman (1959/2002) is that notion of the role. Like an actor or actress, we all play different parts in the everyday. With those roles come certain norms, expectations, ideals, and traits which, like a performer, require the individual to adopt or adapt in order to ‘look the part’. For instance, as a lecturer at a university, there are certain traits and norms that come with the role. That includes how to dress, act, behave, emotions and even the mannerisms that one uses when teaching. These things have to be done properly, otherwise, the audience (the students) will not believe the authenticity of the lecturer, and perhaps reject them altogether. Think about all the roles you play in everyday life – what sorts of norms, even dress standards, do you think are required to perform them?

Watch this short presentation [1:58] on Goffman’s ‘performed self’ for a brief explainer of his theory.

For Goffman (1959/2002), the action of performing the role, or in other words your identity, is not a one-way communication, as the above video makes clear. Rather, just like being on stage as a performer, your success in convincing people of your performance is reliant on audience participation, and their response to you. Goffman (1959/2002) argues that if the audience does not believe, or does not accept your performance, they will not accept you or be influenced by you (very important in politics), and may even provide negative responses (think of audiences booing for instance). He also argues (1959/2002, p. 17) that the performer themselves needs to be convinced of the “impression of reality” – in other words, you need to be convinced yourself that you are suited to the role. When you and the audience have favourable communication verbally and non-verbally to one another, your identity (in that role) and your sense of self is affirmed. If the communicative act/performance breaks down, then your identity in that role is challenged or maybe even rejected. As an example, let me (the author) share an experience. When I first started lecturing as a casual staff member, I taught a business class. I came from a humanities and social science background where people dressed a little more casually than most. When I entered the class to tutor for the first time in an evening class, I noticed that most of the people were professionals, dressed in office attire, having come from their work. One of the members of the class said to me from the outset, ‘We did not think you were the teacher but a student in the wrong class!’ The comment made me feel like I was not suited to the role – and next week I showed up in office attire!

Goffman (1959/2002) admits that not all the world is a stage though. We do perform our roles mostly publicly or amongst others, following rules, norms and expectations. Metaphorically, this is what Goffman (1959/2002) calls the ‘front stage’. However, Goffman (1959/2002) also refers, to the ‘backstage’ where people can loosen themselves from the roles of everyday life, and adopt different props, clothes, mannerisms and actions that would otherwise contradict their front-stage performances. They are also places where people prepare, away from the audience’s eyes for their roles on the front stage. Simone de Beauvoir (1952/2023) for instance described the different activities that a woman has to go through in order to prepare herself for the front-stage performance of being a ‘woman’. Importantly, the backstage is a place kept hidden from view. It contains both the secrets of the performance, but also, the potential for discrediting information about our public identities, that we seek to keep away from view. Unfortunately, the audience can at times discredit our identities, even when in view.

This might seem ultimately silly to think about, and maybe obvious. However, for someone like Goffman (1959), this playing of roles and the audience response is fundamental to how we live our lives and develop our identities. At times, we also live our identities according to the ideas or expectations that people have of our external traits or characteristics. Our ethnicities, gender, height, weight and so on, can be laden with norms or stereotypes about who we are by other groups/people. Howard Becker (1928-2023) in his work, described this phenomenon as ‘labelling’. Becker (1963) argued that at times, we tend to view how people act or present themselves as deviant. Specifically, “whether a given act is deviant or not depends in part on the nature of the act […] and in part what other people do about it” (Becker, 1963, p. 33). As such, there are no inherently ‘deviant’ people out there (remember symbolic interactionism rejects biological reasoning here), rather the process of labelling someone or some action as ‘deviant’ is founded in the relational. In other words, if a group of people collectively agree that something is deviant (or someone) they will declare it as such. Unfortunately for someone like Becker (1963), if someone is labelled deviant, they might adopt what he calls a deviant identity.

Goffman (1963/2009) takes this further by arguing that through dramaturgical analysis, we can see how the audience will carry with them certain ideas that will stigmatise certain people. For Goffman (1963) there are three general types of stigmas, physical, character and ethnicity or religion. Stigmas work to degrade someone’s identity and sense of self in the interaction that exists between the performer and the audience. A stigma can limit someone’s role, discrediting them immediately in the eyes of the audience, or worse still pre-empting their behaviour through certain degrading ideas. Stigmatisation involves reducing the person to the traits that an audience identifies in them, and as a result, positions them as abnormal, an outsider, and even potentially, below human. Stigma can operate in various ways in our society and interactions with others, from the micro-level to the macro as we have seen throughout history with genocides. For Goffman (1963), it is just as important to recognise what stigmas are, as it is to understand how the stigmatised person responds. For him, some people may try and correct their identities, and overcome stigma. For others, they may adopt the stigma into their personality or sense of self and accentuate their differences. Furthermore, for others, their stigmas might lead to success in certain areas of life, but this only serves to reinforce stereotypes, and the person’s identity.

Symbolic interactionism is a significant attempt in sociology’s history to try and understand identity, and how they are constructed, not through macro cultural concepts (as Durkheim might argue), but rather as an emergent process of interaction. One of the criticisms of this approach is that it focuses too heavily at times on the micro, meaning that we can never say anything of substance to broader society (Alexander & Smith, 2018). Furthermore, and this is potentially a criticism of sociology, there is a heavy emphasis on identity, action and behaviour, being constituted through social interaction. This tends to deny other important contributors, including our genetic, biological, evolutionary, and neuroscience makeup (Kivisto, 2011). Symbolic interactionists dismiss these, and in some respects deny a more holistic view of human interaction. We know for instance, that certain responses we have to different social stimuli can be entirely automatic, according to neurological changes that are programmed into us. For instance, flight, fight or freeze responses to overly stressful or threatening situations are defence mechanisms developed via evolution (Donahue, 2020). We also know that emotions are deeply important to decision-making, and not all our reflections on who we are come from places of logic or reason (Stets, 2005). Regardless of these critiques, symbolic interactionism is a unique sociological approach to understanding identity in the contemporary world.

In Summary

The key takeaways from this chapter are as follows:

- Culture and identity are hard to define as several theorists have defined them in different capacities.

- Durkheim contested that culture in a secular society could still have elements of the sacred and profane to increase feelings of collective togetherness.

- Weber argued that rationalisation, and disenchantment, were having a major impact on cultural life, standardising and rationalising all.

- Simmel argued that modern culture had grown too large, overwhelming the individual, and disabling an ability to cultivate identities.

- The symbolic interactionists argue that our roles in everyday life define much of who we are as identities, and we reflect on these through our relations with others.

- Goffman’s presentation of the self arguments, further this by arguing that we present ourselves in our roles, but need the audience to be convinced of our performance.

As mentioned in the introduction to this chapter, there is too much to cover for one chapter on culture and identity. Below is a list of recommended resources to assist in developing knowledge of these two important concepts.

Recommended Resources

Alexander, J. C., Jacobs, R., & Smith, P. (2010). The Oxford handbook of cultural sociology. Oxford University Press.Blackshaw, T. (2005). Zygmunt Bauman. Routledge.

Blumer, H. (1986). Symbolic interactionism: Perspective and method. University of California Press.

Elliott, A. (2021). Contemporary social theory: An introduction. Routledge.

Fardon, R. (2002). Mary Douglas: An intellectual biography. Routledge.

Giddens, A. (2016). Modernity and self-identity. In W. Longhofer, D. Winchester & A. Baiocchi (Eds), Social theory re-wired (2nd ed., pp. 512-521). Routledge.

Harrington, A. (2005). Modern social theory. Oxford University Press.

Inglis, D., & Almila, A. M. (Eds.). (2016). The Sage handbook of cultural sociology. Sage.

Six, P. (2018). The institutional dynamics of culture, volumes I and II: The new Durkheimians. Routledge.

Sørensen, M., & Christiansen, A. (2012). Ulrich Beck: An introduction to the theory of second modernity and the risk society. Routledge.

Spillman, L. (2020). What is cultural sociology? John Wiley & Sons.

Spykman, N. J. (2017). The social theory of Georg Simmel. Routledge.

Turner, B. S. (1996). For Weber: Essays on the sociology of fate. Sage.

References

Adam, B. (2009). Cultural future matters: An exploration in the spirit of Max Weber’s methodological writings. Time & Society, 18(1), 7-25.

Adorno, T. W., & Horkheimer, M. (1997). Dialectic of enlightenment. Verso.

Alexander, J. C., & Smith, P. (2018). The Strong Program in cultural sociology: Meaning first. In L. Grindstaff, M-C. M. Lo & J. R. Hall (Eds.), Routledge handbook of cultural sociology (2nd ed., pp. 13-22). Routledge.

Bartmanski, D., & Woodward, I. (2018). Vinyl record: A cultural icon. Consumption Markets & Culture, 21(2), 171-177.

Baudrillard, J. (1983). Simulations. Semiotext(e).

Bauman, Z. (2005). Liquid life. Polity Press.

Beck, U. (1992). Risk society: Towards a new modernity. Sage.

Becker, H. S. (1963). Outsiders. Free Press.

Bennett, J. (2001). The enchantment of modern life: Attachments, crossings, and ethics. Princeton University Press.

Blumer, H. (1969). Symbolic interactionism: Perspective and method. Prentice-Hall.

De Beauvoir, S. (2023). The second sex. In W. Longhofer, D. Winchester & A. Baiocchi (Eds), Social theory re-wired (2nd ed., pp. 346-354). Routledge. (Original work published 1952)

Donahue, J. J. (2020). Fight-Flight-Freeze system. In V. Zeigler-Hill & T. K. Shackelford (Eds.), Encyclopedia of personality and individual differences (pp. 1590-1595). Springer International Publishing.

Douglas, M. (2003). Purity and danger: An analysis of concepts of pollution and taboo. Routledge. (Original work published in 1966)

Durkheim, E. (2013). Emile Durkheim: The division of labour in society (2nd ed.). Palgrave Macmillan Basingstoke. (Original work published 1912)

Durkheim, E (1995). The elementary forms of religious life. Free Press New York. (Original published 1912)

Foucault, M. (1975). Discipline and punish. Gallimard.

Geertz, C. (1973). The interpretation of cultures. Basic Books.

Giddens, A. (1991). Modernity and self-identity: Self and society in the late modern age. Polity.

Gibson, M. (2008). Objects of the dead: Mourning and memory in everyday life. Melbourne University Publishing.

Goffman, E. (2002). The presentation of self in everyday life. Penguin. (Original work published 1959)

Goffman, E. (2009). Stigma: Notes on the management of spoiled identity. Simon and Schuster. (Original work published 1963)

Hertz, R. (2013). Death and the right hand. Routledge. (Original work published 1909)

Kivisto, P. (2011). Illuminating social life: Classical and contemporary theory revisited. Pine Forge Press.

Mauss, M. (1990). The gift: The form and reason for exchange in archaic societies. Routledge. (Original work published 1925)

Mauss, M. (2013). Seasonal variations of the Eskimo: A study in social morphology. Routledge. (Original work published 1906)

Mead, G. H. (1972). Mind, self, and society from the standpoint of a social behaviorist. University of Chicago Press. (Original work published 1934)

Osbaldiston, N., & Petray, T. (2011). The role of horror and dread in the sacred experience. Tourist Studies, 11(2), 175-190.

Pyyhtinen, O. (2018). The Simmelian legacy. Bloomsbury Publishing.

Riley, A. T. (2010). Godless intellectuals?: The intellectual pursuit of the sacred reinvented. Berghahn Books.

Ritzer, G. (2010). Enchanting a disenchanted world: Continuity and change in the cathedrals of consumption. Pine Forge Press.

Ritzer, G. (2011). The McDonaldization of society 6. Pine Forge Press.

Simmel, G. (1997). Simmel on culture: Selected writings. Sage.

Simmel, G. (2010). The view of life: Four metaphysical essays with journal aphorisms. University of Chicago Press.

Simmel, G. (2011). The philosophy of money. Routledge. (Original work published 1900)

Smith, P. (1999). The elementary forms of place and their transformations: A Durkheimian model. Qualitative Sociology, 22(1), 13-36. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1022179131684

Smith, P. (2008). Punishment and culture. University of Chicago Press.

Spencer, B., & Gillen, F. J. (2010). Native tribes of central Australia. Cambridge University Press. (Original work published 1899)

Stets, J. E. (2005). Examining emotions in identity theory. Social Psychology Quarterly, 68(1), 39-56.

Swidler, A. (1986). Culture in action: Symbols and strategies. American Sociological Review, 51(2), 273-286. https://doi.org/10.2307/2095521

Turner, J. H., Beeghley, L., & Powers, C. H. 2007. The emergence of sociological theory (6th ed.). Thomson Higher Education.

Weber, M. (2002). The Protestant ethic and the spirit of capitalism and other writings. Penguin Publishing. (Original work published 1905)

Weber, M. (2012). Science as a profession and vocation. In H. H. Bruun & S. Whimster (Eds.), Max Weber: Collected methodological writings, (pp. 335–353). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203804698

West, B. (2022). Finding Gallipoli: Battlefield remembrance and the movement of Australian and Turkish history. Springer Nature.

Woodward, I. (2007). Understanding material culture. Sage.

Refers to objects, people, ideas or other things that are considered above the everyday and which need to be protected at all costs. Emile Durkeim argues that sacred things represent group identity - such as a cross at a Christian church.

The oppositive of the sacred. For Emile Durkheim, the profane is the everyday world which requires separation from sacred things.

Relates to Baudrillard's theory of modern life – where copies of original things, become the 'real' for contemporary culture.

pertains to the culture activities and artifacts that are usually aligned with the upper middle to upper classes. For instance, opera music or polo.

pertains to the cultural activities and artifacts that are usually aligned with lower middle and lower classes. For instance, football or rugby league.

Refers to the sociological and psychological make-up of who we are as people – both in how we identify ourselves, and how others identify us through different characteristics and roles.

The idea that people take on information, process it through their own logic, reason and emotions, and make decisions accordingly. Reflexivity denotes a turn from premodern societies, where choices were limited, to one of late modernity where choices are abundant in life, but also require deep thinking and reflecting, and weighing up risks with benefits.

A school of thought, based on the scholarship of Emile Durkheim, but operationalised by Talcott Parsons that aims to create theory/knowledge on how societies can best function as a whole with different roles.

A term from Emile Durkheim's work that reflects the broad norms and values that bind together a culture which enables but also constrains individual social action.

Refers to the time period where Europeans in particular began to dramatically and quickly change the organisation of society, culture and economy. This included the rise of the nation-state, rationalism, science, organised labour and the intensification of urbanisation and growth of cities. Sociological figures refer to modernity demarcate it from pre-modern times where societies were arranged far differently.

Denotes the smaller community-based society which has strong social ties, less diverse roles and a stronger relationship to community organisations like religion.

Denotes the broader societal shift to societies that are large, have diverse roles and occupations, less social integration and less commitment to community institutions such as religion.

Refers to the disconnection of the individual to the collective, and into a more isolated, individualised lifestyle.

An economic system that dominates the world today in which society's economic activity is organised around trade for profit and private property.

Refers to the theory from Max Weber that the social and cultural worlds we live in are increasingly becoming rationalised – in other words, technically or scientifically explained. Weber also argued that this would increase until there were very few things left that could be explained without science (such as religion).

An approach within social science theories that argues the social world cannot be understood through natural sciences. Rather, society is messy and complex and research can only obtain an understanding of how people interpret or perceive the world around them.

The term used to denote the gradual adoption of scientific and other 'rational' means or knowledge to understand social life. In other words, the removal of myths and religion as the main driver for understanding our worlds.

A period of time in Europe where human reasoning was privileged in the pursuit of truth (for instance science) over other approaches (for instance religion/mythology)

A philosophical approach to understanding truth that focuses on logic and science and rejects alternative approaches such as metaphysics.

A school of thought largely constructed by the famed 'Chicago School' (Blumer, Goffman, Garfinkle, etc.) which focusses on the emerging nature of society through micro-interactions, group members and symbolism.