1 What is Criminology?

Nadine M. Connell

Learning Objectives

- To understand and define criminology and the elements of a good criminological theory.

- Identify and begin to critically assess the different ways of knowing and be able to understand that different ways of knowing will be useful for different things.

- Recognise the different ways that theories can be classified and be able to classify them appropriately.

Before You Begin

- When you hear the word criminology, what do you think about? Do you think you could define it for someone?

- How do you know what you know? Are there any things that you know are real but you would have a hard time explaining to somehow how you know it?

- Have you ever thought about human nature, or why people act the way that they do? Do you think people are born with a certain personality? Why or why not?

INTRODUCTION

What is Criminology?

Welcome to the study of criminology and criminal justice. Have you stopped and wondered what actually is criminology? If you’re like most of us in this discipline, someone has already asked you a question about your study or your work and probably made some wild assumptions along the way. For instance, if you tell people that you are studying criminology, do they automatically assume that you must be collecting evidence? Or interviewing individuals who may have committed crimes? And if they have watched too many movies, they may think you are going to be an undercover spy who will lure international criminals to their demise. Overall, a very busy day!

If you are not exactly sure what criminology is, you are not alone. Criminology as we know it today in a university setting is a relatively new discipline compared to many other well-established branches of social sciences, like philosophy or sociology. But the search to understand why individuals commit anti-social and criminal behaviour has been going on for as long as humans have been around. After all, every version of society has had people in it who did not follow the rules. Of course, the reasons why people did not follow the rules were thought to be quite different for most of history and often related to the possibility that someone was possessed by a demon. That thinking has long since changed.

Criminology as we know and study it today can be traced back to the late 18th century (the 1700s) when societies, especially in Europe, slowly began to rethink their beliefs about the nature of humans. In particular, the Age of Enlightenment, or the Age of Reason, brought with it new ideas about the nature of humanity. In particular, we see scholars begin to believe that humans make decisions based on rationality and they begin to promote the use of the scientific method to understand the world around us. These advancements were happening in many different scholarly fields and the study of human behaviour was only one discipline to benefit. Taken together, this was the catalyst to the world of criminology we know today.

The most enduring definition of criminology is one that was first described by the sociologist Professor Edwin Sutherland. Professor Sutherland defined criminology as the comprehensive study of law-making, law-breaking and law-enforcing mechanisms (Sutherland et al., 1992). This definition is an incredibly useful one as we look to explain not only individual behaviour but also how the criminal justice system (e.g., laws, policies, and government) controls individual behaviour. After all, as we will discuss throughout this book, whether or not something is a crime is related to whether or not the people in charge think it is a crime. It also recognises the inherent interdisciplinarity in criminology. Much of what we know is also connected to philosophy, law, sociology, psychology and political science, just to name a few disciplines! In fact, many of the professors who teach you may have degrees in related fields because they studied crime from a sociological or a psychological context. That is one of the reasons that criminology studies so many different aspects of behaviour.

Can you think of behaviours that are dangerous or perhaps immoral, but not criminal? What about behaviours that are criminal but do not create harm for others? Many things that used to be illegal in our lifetime are now legal and celebrated. A very good example of this is same-sex marriage. Australia did not legalise same sex marriage until December 2017! Another good example is the way that our society has changed our understanding about the dangers of family violence. Traditionally, violence in the home was not considered anyone’s business and was not always illegal in all places (Please note that family violence is still legal in some countries but thankfully Australia is not one. That doesn’t mean that we don’t have more work to do though!). Now, we understand the damage that domestic and family violence does to families, children, and society. The decision to criminalise certain acts, therefore, is always a political one.

Because of that, criminologists will often refer to anti-social or deviant behaviour when talking about crime. Crime is codified by law but anti-social behaviour and deviance encompass a wide range of behaviours that are still of interest to the study of crime. Many of these other behaviours are also committed by people who break the law. A good example of this is childhood bullying. Bullying in school is not against the law. But we do know that young people who bully their classmates are more likely to grow up to commit crimes, so it is an important early behaviour to pay attention to (Piquero et al., 2013).

What does the study of law-making, law-breaking and law enforcement look like? Our goal as criminologists is to objectively study the nature, extent, causes and control of anti-social and deviant behaviours (Snipes et al., 2019). We investigate both the behaviours themselves and the societal responses to them, at both the individual and the institutional levels. Central to that is our definition of crime, which influences the way that we attempt to explain criminal behaviour. In Chapter 2, you will have the opportunity to think more critical about crime and how it is defined, but for now, we will use a very basic dictionary definition. Crime is an act deemed socially harmful or dangerous, that is specifically defined, prohibited and punished under criminal law.

The definition of crime is important because different criminological theories will attempt to explain different kinds of criminal behaviour, although we will soon learn that the more types of behaviour a theory can explain, the better.

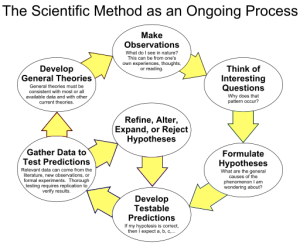

Criminology and Science

What does it mean to be objective? Traditionally, this has meant the application of the scientific method in order to observe the world and make sense of our observations. You may remember talking about the scientific method in some of your classes in primary and high school. Figure 1.1 shows a simplified example of the ongoing process, which includes the steps: Make observations, Think of interesting questions, Formulate hypotheses, Develop testable predictions, Refine, alter, expand or reject the hypotheses, Gather data to test predictions and Use the data to develop general theories, which leads back to the Make Observations step. Our goal, by using the scientific method, is to make statements about the relationships between observable phenomena. Our statements should be as free from bias as possible, although it is very important to remember that all of us have some inherent bias that will affect our interpretations of our observations. These statements become theories (Babbie, 1989). That is why it is very important to be willing to reflect on our work, be critical of our ideas and welcome other people to offer a fresh perspective.

The Scientific Method as an Ongoing Process by ArchonMagnus licensed under CC-BY-SA 4.0

We use the scientific method to collect observations called data (Hartley, 2011). We then try to come up with explanations for why we see the things that we see. After we develop these theories, we test them using empirical methods. By constantly repeating this process, we can begin to identify patterns in behaviour. From these observations we can begin to ask questions about why things happen. Theories are statements about the relationships between these observations (Babbie, 1989; Stinchcombe, 1968). These questions become hypotheses, which are testable. We collect more data to test these hypotheses, generally in a very organised and systematic process, and sometimes we will have to refine or reject our hypotheses. We use these outcomes to develop our general theories of behaviour. And then we start all over again.

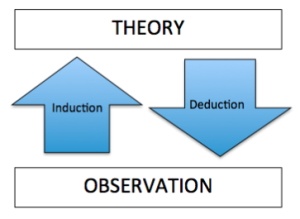

We can technically start this process at either the top or the bottom of the cycle, as shown in Figure 1.2. When we start with our observations and use them to create a theory about the world, we are undergoing an inductive process. When we start with a theory and collect observations to test our theory, we are undergoing a deductive process. You will learn more about this in your research methods classes but what is important to know is that both ways are legitimate ways to create theories of human behaviour.

Qualitative vs Quantitative by Jaime Anstee licensed under CC-BY-SA 4.0

One important question that comes up a lot is how a theory is different from common sense. This is a very reasonable question. After all, common sense comes from observing the world around us. But one limitation of common sense is that it is limited by our own experiences, including where – and when – we live. One famous example is that of the black swan. In Europe, swans are white. But when Dutch explorer Willem de Vlamingh arrived in Australia in 1697, he encountered a black swan. Of course, to Australian First Nations’ peoples, it was common sense that a swan would be black! This is a silly example of how we only know what we know, so processes like empirical inquiry can help us expand our experiences into patterned observations that can then be generalised to other experiences.

Ways of Knowing

Theories are, of course, only one way we know what we know. Throughout history there have been other ways that individuals and societies came to conclusions about the nature of life and humanity. These are the most common ways of knowing that are generally discussed:

Authoritarian Way of Knowing

This involves deferring to socially recognised experts for knowledge dissemination. These experts, often equipped with formal credentials, hold prominence in specific domains. There are also other ways that individuals can be considered experts. While Western society prioritises formal credentials, other societies prioritise an individual’s level of respect and standing in a community, which is usually given based on socially agreed upon qualities and actions. In working within the criminal justice system, it is essential to recognise that other types of expertise, like community-based expertise, which may not always align with conventional academic standards, are also incredibly valuable.

Mystical Way of Knowing

Mystical ways of knowing encompass intuitive, spiritual, or religious insights that guide our knowledge about what is “right.” Such traditions gave way to what was known as trial by battle in the Middle Ages, which eventually morphed into trial by ordeal (Gehring and Batista, 2017). Many of you will be familiar with the idea of trial by ordeal if you have heard of stories of trials for those accused of witchcraft or the atrocities of the Spanish Inquisition. Thankfully such approaches to punishment are no longer common and we determine innocence or guilt in much more reasonable ways today.

Logic-Rational Way of Knowing

Many people use logic to come to conclusions about the world around us (Beccaria, 1963). Logic and rationality can be very useful tools to determine truth but are limited in that people do not always act in logical or rational ways. While logical frameworks provide valuable insights, we must acknowledge their limitations, as truth may transcend conventional logic in certain contexts.

Scientific Way of Knowing

This brings us back to where we started: a way of knowing based on observation and objectivity. The use of empirical observations can help us test our hypotheses and help us refine our understanding of the world. Over time, the consistent support for our hypotheses will give us more confidence that our theories are reasonable ways to explain the world.

The Parts of a Theory

Now that we have established a shared understanding of the definition of criminology and have some familiarity with the use of observation to help us develop theories, it is time to delve a little deeper into the anatomy of a theory. Understanding the components of theories is crucial for both critiquing existing theories and understanding their contextual significance. Every theory comprises two essential elements: articulated propositions and unarticulated propositions. These components collectively form the foundation of a theory’s structure and implications (Gouldner, 1970).

Articulated Propositions

An articulated proposition is a formally expressed statement that describes the relationships that link variables that make up a theoretical explanation. These statements describe the causal mechanisms underlying the phenomenon of study. For example, in Chapter 5 you will learn more about strain theories, which have articulated propositions that explain the relationship between societal goals and the occurrence of deviant behaviour. Importantly, these propositions are expected to align with observed reality, providing a basis for continued testing.

Unarticulated Propositions

Contrary to their articulated counterparts, unarticulated propositions represent implicit beliefs and assumptions that are inherent to a theory. These assumptions, usually reflecting the perspective of the theorist, encompass broader notions about human behaviour and societal dynamics. Unarticulated propositions often influence a theory’s policy implications and practical applications. For instance, implicit beliefs about the nature of criminality may shape recommendations for crime prevention or rehabilitation strategies. If we think people can change, we may implement a different set of programs than if we think that people cannot improve.

Goals of a Theory

A theory serves four primary goals: explanation, prediction, summarisation, and utility.

- Explanation: a theory attempts toto explain the phenomenon under study by making statements about its underlying mechanisms. In our case, we are trying to explain the phenomena of crime and anti-social behaviours.

- Prediction: a theory is only useful if it can predict future occurrences based on the established causal relationships of interest. If we cannot use a theory to predict when and where crime will happen, we do not have a very useful theory.

- Summarise: a theory should accurately summarise the existing body of knowledge in its domain. A theory about crime should also be explain why our current knowledge about crime is correct.

- Use Value: a theory needs to have practical utility, offering insights that inform policy decisions and interventions. After all, good theory will make good policy. And without a strong understanding of theory, we will not be able to properly critique and assess our policy (Paternoster and Bachman, 2001).

Criteria for Evaluating Theory

There are several different lists of criteria that exist to help us determine if we have a good theory. We will use the criteria from the well-respected criminologist Professor Ronald Akers[1] (1994). You will learn more about his work in Chapter 10. According to Professor Akers, a good theory should be:

- Internally consistent and non-tautological. Is the theory logical? Does the theory make sense? Does the theory avoid circular reasoning?

- Testable. Can the theory be tested? Remember, if we cannot develop a way to observe something, we cannot test it.

- Empirically supported. Has the theory received some empirical support? When researchers conduct studies to test the theory, have they found support for it?

- Parsimonious yet broad. Is the theory broad in scope, yet parsimonious? Parsimonious really means frugal but in this setting, we use it to mean simple and without extra propositions. The theory needs to be able to explain more than a small subsection of crime and it needs to do so with as few major concepts as possible.

- Real world use. Does the theory have some “real world” use? Can we use the theory to do something about crime in society?

Classifying Theory

There are several different ways that we can classify theories in criminology. These are very useful distinctions as we try to understand which theories are able to explain behaviour in which circumstances. Society is complex and while we strive for the most parsimonious explanation of social behaviour, those explanations also come from a place of our own understanding of the world. The most common ways to classify a theory are:

Worldview or Paradigm

Level of Analysis

Underlying Assumptions

Worldview or Paradigm

Theories can be classified based on their underlying assumptions about social order. There are three main paradigms that criminologists use.

Consensus Paradigm

The consensus paradigm posits that society functions harmoniously and that there is general agreement on what is – and what is not – acceptable. In this type of worldview, criminal behaviour serves a functional role because it reinforces the agreed upon social norms of behaviour. One example of a consensus paradigm is classical strain theories, which you will learn more about in Chapter 5.

Conflict Paradigm

The conflict paradigm highlights societal divisions and power struggles. Conflict criminology is strongly rooted in the work of Karl Marx, who argues that crime arises from class conflicts. In the conflict paradigm, capitalism perpetuates inequality and then crime. There are several different types of conflict theories and you will learn about three of them in Chapter 14.

Symbolic Interactionism

Symbolic interactionism focuses on how social interactions shape individual behaviour. Crime is perceived as a violation of social norms. One example of a symbolic interactionist theory is labelling theory, which highlights how societal reactions to deviance can influence individuals’ self-concepts and future actions. You will learn more about these theories in Chapter 13.

Level of Analysis

Theories are often categorised into micro and macro levels of analysis:

Micro-Level Theories

Micro-level theories examine individual processes contributing to criminal behaviour.

Macro-Level Theories

Macro-level theories focus on broader societal factors influencing crime rates. These theories are often considered social or institutional level theories.

Underlying Assumptions

The underlying assumptions of a theory encompass our perspectives on social order and beliefs about human nature:

Normative vs. Relativistic Definitions

One thing that a theory relies on is an underlying assumption or belief about social order (Lemert, 1981). After all, if you are going to explain why people commit anti-social behaviours, you also have to explain why those behaviours are considered anti-social to begin with. Normative assumptions suggest a shared consensus on morality, where everyone agrees upon what is moral and right. Relativistic assumptions argue that morality is contingent upon power dynamics. For example, consensus theories assume a shared understanding of right and wrong, while conflict theories acknowledge power differentials in defining morality.

Assumptions about Human Nature

Theories vary in their beliefs about human nature, influencing the ways in which they propose to interpret of criminal behaviour. One of the defining debates in criminology is whether “nature or nurture” causes individuals to commit crime. There are three main assumptions that criminological theories can make about human nature. The first is that human being are inherently good and have to be pushed to commit crimes. The second is that human beings are inherently bad, or at least out to maximise their own pleasure, and have to be deterred or stopped from committing crime. The third possible assumption about human nature is known as the tabula rasa argument, or that everyone is born as a blank slate. Through the process of living and learning, we have different ideas imprinted into our personality. As you read through the different chapters in this textbook, I encourage you to see if you can determine what assumption of human nature each theory starts with.

Connecting Theory to Policy

At this point, you may be asking yourself what all of these things have to do with the reality of working in the criminal justice system. It is a very fair question. Many of the concepts in this chapter are, after all, a little bit vague and do not seem to have immediate importance for the day to day work of criminal justice agencies. But remember what we said earlier in this chapter: good theory helps create good policy (Paternoster and Bachman, 2001). How does this work?

As we use the scientific method to observe reality to help us create testable hypotheses that explain the reasons that humans act the way that they do, we refine our understanding of the world and create the building blocks of evidence that will help us determine what policies are most likely to be effective in reducing crime. The process of collecting this evidence and reporting it back to society to help create better policy is called translational research (Blomberg et al., 2024). Every discipline has some version of translational research. You encounter translational research every day. Whether it be a public health message to wash your hands (for 20 seconds!) or a reminder to wear your seatbelt, most government policy has its origins in a research recommendation.

Because this evidence is so important for society at large, we have a responsibility to take the way that we investigate this claims very seriously. Criminologist Professor Robert Sampson said it best: “Data never “speak for themselves”—making sense of causal patterns requires theoretical claims about unobserved mechanisms and social processes no matter what the experiment or statistical method employed” (Sampson, 2010, p. 491, italics in original). Collecting data and making observations is only one part of the process. It is up to us to make sense of those observations so that we can inform meaningful change.

A good example of when this backfires is example of school violence (Blomberg et al., 2024). We know that school violence can be improved by improving school climate, helping students create strong friendships, and incorporating successful bullying prevention programs (Connell et al., 2013; Connell et al., 2014; Schell-Busey et al., 2023; Turanovic and Siennick, 2022). However, schools in many juridsictions insist on implementing zero-tolerance policies and adding more police officers to schools (Han and Connell, 2021; Turnanovic et al., 2022). This is why we need strong theory to guide strong policy; translational research is the way to get there.

Conclusion

At this point in time, you may feel a little overwhelmed. But don’t worry; soon this will all become very clear. In the coming chapters, you will learn about the different theoretical frameworks that criminologists use to explain all sorts of deviant, anti-social and criminal behaviour. What is important now is that you understand that the process of creating, testing and refining a theory of human behaviour is not a random one. And beyond that, there are a lot of underlying assumptions that we bring to the conversation, even if we are trying to be objective. Objectivity is incredibly difficult and what is more important is to articulate and be honest about the assumptions that are inherent in the theories and thought processes that we are going through.

Criminology has many theoretical explanations of behaviour. As you read through the following chapters, think about which ones most resonate with you and why. What are the assumptions that you have about society and humanity that drive your opinions about which theories make the most sense to you? By the end of this course, we hope that you have a firm understanding of the different explanations of criminal and deviant behaviour, are able to examine these explanations with a critical eye and feel comfortable about the different ways that good theory can begin to inform good policy. Because at the end of the day, our goal is to create good policy that helps keep people and societies safe and well supported.

Check Your Knowledge

Discussion Questions

- How do we identify if a criminological theory is good?

- How does the scientific method support the creation and refinement of new explanations of social behaviour?

- What are the underlying assumptions that go into the ways we explain anti-social and criminal behaviour? Why is it important to be able to identify and articulate these assumptions?

REFERENCES

Akers, R. L. (1994). Criminological theories: Introduction and evaluation. Roxbury Publishing Company.

Babbie, E. R. (1989). The practice of social research. Wadsworth Publishing Company.

Beccaria, C. (1963/1767). On crimes and punishments (Introduction by H. Paolucci, Trans.). New York, NY: Macmillan.

Blomberg, T. J., Copp, J. E., & Turanovic, J. J. (2024). Challenges and prospects for evidence based policy in criminology. Annual review of Criminology, 7, 143-162.

Connell, N. M., Schell-Busey, N. M., Pearce, A. N., & Negro, P. (2014). Badgrlz? Exploring sex differences in cyberbullying behaviors. Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice, 12(3), 209-228. https://doi.org/10.1177/1541204013503889

Connell, N. M., Barbieri, N., & Reingle Gonzalez, J. M. (2015). Understanding school effects on students’ willingness to report peer weapon carrying. Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice, 13(3), 258-269. https://doi.org/10.1177/1541204014544512

Gehring, K. S. & Batista, M. R. (2017). Crimcomics: Origins of criminology. New York: Oxford University Press.

Gouldner, A. W. (1970). The coming crisis of western sociology. New York: Basic Publishing.

Han, S., & Connell, N. M. (2021). The effects of school police officers on victimization, delinquency, and fear of crime: Focusing on Korean youth. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 65(12), 1356-1372. https://doi.org/10.1177/0306624X20946933

Hartley, R. D. (2011). The scientific method and the research process in criminology and criminal justice. In Snapshots of Research: Readings in Criminology and Criminal Justice (pp. 1-15). SAGE Publications, Inc., https://doi.org/10.4135/9781452230658

Lemert, E. M. (1981). Issues in the Study of Deviance. The Sociological Quarterly, 22(2), 285-305.

Paternoster, R., & Bachman, R. (2001). Explaining crime and criminals. Oxford University Press.

Piquero, A. R., Connell, N. M., Piquero, N. L., Farrington, D. P., & Jennings, W. G. (2013). Does adolescent bullying distinguish between male offending trajectories in late middle age? Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 42(3), 444-453. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-012-9883-3

Sampson, R. J. (2010). Gold standard myths: Observations on the experimental turn in quantitative criminology. Journal of Quantitative Criminololgy, 26(4):489–500.

Schell-Busey, N., Connell, N. M. & Walding, S. (2023) Examining gender differences in a social norms prevention program for cyberbullying. International Journal of Bullying Prevention (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42380-023-00196-4

Snipes, J. B., Bernard, T. J., & Gerould, A. L. (2019). Vold’s theoretical criminology. Oxford University Press.

Stinchcombe, A. L. (1968). Constructing social theories. New York: Harcourt, Brace & World.

Sutherland, E. H., Cressey, D. R., & Luckenbill, D. F. (1992). Principles of criminology. Altamira Press.

Turanovic, J. J. & Siennick S. E. (2022). The causes and consequences of school violence: A review [pdf]. National Institute of Justice Rep. NCJ 302346, Office of Justice Programs, Washington, DC.

Turanovic, J. J., Pratt, T. C., Kulig, T. C., Cullen, F. T. (2022). Confronting school violence: A synthesis of six decades of research. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

[1] For more information about Professor Ronald Akers, check out this interview with Professor Gary Jenson for the Oral History Project of the American Society of Criminology.