9 Nature versus Nurture: Biosocial Theories of Crime

Antoinette L. Smith and Tracy Meehan

Learning Objectives

- Understand the fundamental concepts and principles of biosocial criminology and investigate how biological and social factors interact to influence aggression and antisocial behaviour.

- Identify and compare three major areas of biosocial criminological research: nutrition; genetics; and traumatic brain injury.

- Be able to address historical and current criticisms of biosocial criminology and understand the role of ethics and morality in this type of criminological approach.

Before You Begin

- How does your environment affect you? Do you cranky when you are hungry? Anxious or annoyed when you are cold? Take a moment to think about how your body reacts to your environment. Does that affect your behaviour?

- Have you ever read or heard about instances where medical or scientific professionals have acted in an unethical or immoral manner? What types of situations? How did this make you feel?

- It’s easy to understand where we inherit our physical traits. But what about our personality traits? Do you share personality traits with the people you grew up with or the people you are related to? If you had to make a bet, would you bet that you inherited those similar traits or learned them?

INTRODUCTION

It’s no surprise that we inherit traits from our families. It may be our height or our hair colour or any number of other physical traits. But of long interest in criminology is whether personality traits are inherited, particularly those relating to crime and aggression. The long-standing nurture vs. nature debate in social sciences has advocates on both sides but these days, we can sum it up by saying “it depends.” The research into the overlap between biological and social explanations of crime is known as biosocial criminology (Barnes et al., 2015). The body of work exploring criminal behaviours within this discipline is a broad framework borrowing theories and concepts from at least five other disciplines, including: evolution, biology, genetics, neurology and sociology.

Biosocial theory helps us understand the interplay between internal behavioural influences, such as the ways our brains, bodies and genes work, and external behavioural influences, including who we spend time with, the societies we live in, and the cultures we experience. Biosociology offers a more comprehensive explanation for criminal behaviours, rather than traditional or standalone theories have provided. If you have watched any historical detective movies, you may have heard about the study of ‘phrenology,’ when people thought that bumps and divots in our skull could help determine criminals from non-criminals[1] (Bedoya & Portnoy, 2023; Larregue & Rollins, 2019). While we now know this was a silly idea, the study of phrenology helped usher in a period of increased data collection and evidence based scientific endeavors, known as positivism. This early form of biological research has changed dramatically over the decades into what we now know as biosocial criminology.

We have come a long way since criminals were catalogued by their head bumps and limb lengths. And what we have learned is that biology is not destiny. But it does serve a purpose is helping us understand the relationships between our physical, psychological, social and inherited experiences.

HISTORICAL CONTEXT

Biosocial criminology developed over time by combining research from a range of complementary disciplines, like evolution, genetics, sociology, and environmental theories. During the 19th century, thanks to the work of people like Charles Darwin and Sir Francis Galton, research focused on evolution-based explanations of behaviour. After all, if evolution helped plants and animals change over time, surely it could explain behavioural traits as well (Berryessa & Cho, 2013; Green, 1997). Biosocial theory was first introduced in the 1950s by the German-British psychologist Hans Eysenck, although it did not initially gain much traction in the research community. While recognising the importance of biology in understanding crime, Eysenck also emphasised the importance of social influences like friends and family (Brennan & Raine, 1997).

But one reason that the idea did not gain traction early on was related to the fact that in the 1950s and 1960s, most of the world was still recovering from learning about the atrocities committed during the Holocaust in World War II. During this time, governments and universities began creating new ethics review processes and were more critical about the best ways to study people. Biological research like twin studies where no longer in favour.

As all types of science adopted more ethical and moral principles of research in the late 20th and early 21st centuries, researchers moved increasingly back towards a focus on biosocial explanations of criminality (Rocque et al., 2012). Improved technologies as well as worldwide efforts that made up the Human Genome Project (which began in 1990) sparked more interest in the role that biology could play in helping us understand aggressive behaviour. It is then when we now think of as biosocial criminology re-emerged (Barkow et al., 1995; Tremblay et al., 2005). Over time, other disciplines have been drawn into the conversation, including epigenetics, environment-interactions, and life-course psychology (Fraga et al., 2005; Wortley, 2011).

Table 11.1 Biosocial Theory – Timeline

| 1859 | Darwin published "On the Origin of Species” becoming the foundation for understanding human behaviour through a biological lens. |

| 1869 | Galton, Darwin’s cousin, expanded Darwin’s work exploring the roles of genetics and environmental factors on behaviours. His formative publication “Hereditary Genius: An Inquiry into its Laws and Consequences” paved the way for future twin adoption studies. |

| 1890 | James published "Principles of Psychology” examining the role of instincts in shaping behaviour. His work also explored the role of attention, habit and will in behavioural outcomes. |

| 1950 | Eysenck was the first to introduce the biosocial theory or crime, emphasising the importance of social upbringing in addition to biology when explaining criminality. |

| 1960-9's | Several authors published works on adopted twins demonstrating the roles of “nature” versus “nurture”. The Swedish Adoption/Twin Study of Aging (SATSA) and the Virginia Twin Study of Adolescent Behaviour Development (VTSABD) explored the role of genetics and the environment on criminality. |

| 1960-90's | Emerging from the twin studies, the focus of eugenics research, those who focused on selective breeding to improve genetic qualities, was heavily criticised by academics. Resulting in a shift away from genetic type explorations of criminality. |

| 1975 | The discipline of “Sociobiology” was developed by Wilson in his publication “Sociobiology: The New Synthesis”. He drew attention to the evolutionary nature of behaviours, particularly in social settings. |

| 1992 | Barkow, Cosmides and Tooby compiled a range of essays relating to the evolution of language and behaviours in their work “The Adapted Mind: Evolutionary Psychology and the Generation of Culture”. These essays outlined the evolution of set traits and behaviours leading to the greatest change of survival and reproduction in humans. |

| 2004 | Tremblay furthered the development of biosocial criminology by examining the impacts of social and biological factors on behaviour. His most influential interdisciplinary work was the “Developmental Origins of Aggression” examining early childhood aggression through genetics, biology and environmental factors. |

| 2020's Onwards | Interdisciplinary biosocial advances continue to emerge increasing our understanding of biological and environmental influences on behaviours. In criminology, these findings help shape criminal justice system responses such as rehabilitation programs and intervention responses |

WHAT IS BIOSOCIAL CRIMINOLOGY

There is not one kind of biosocial criminology. In fact, there are several biosocial theories to explain crime and aggression. What they all have in common is an assumption that one’s biology interacts with the environment in which they live, and this interaction affects behaviour. Some biosocial theories focus on the inherited nature of biological traits, such as how hormones can influence aggression. Other biosocial theories focus on how our bodies interact with the world around us, such as understanding the effects of brain injuries or nutritional deficiencies on later life outcomes. What they all have in common is that they investigate how the complex interaction between us and our environments.

The contribution of biology has traditionally been about making connections between biological factors, such as hormones, genetic markers, and biochemical factors, and our behaviour (Raine, 2002). For instance, males are more likely to have higher testosterone levels than females, which has led some to come to the conclusion that men are more prone to aggressive crimes, like assault or intimate partner violence (Burgess & Draper, 1989). Other researchers have examined the structure and function of the brain in trying to understand criminal behaviour, finding connections between the overstimulation or under stimulation certain regions of the brain and aggressive behaviour (Raine et al, 1997; Raine, 2002). Recent research has turned to the role of health, particularly nutrition, on individual behaviour and connections to aggression (Jackson, 2016).

For the remainder of the chapter, we will focus on three major research areas that fall under the umbrella of biosocial criminology: the role of nutrition; genetics; and brain injury.

THEORY APPLICATION

Nutrition and Crime

Have you ever been so hungry that you couldn’t think straight? Or maybe you’ve been uncharacteristically mean to a friend when you were ‘hangry.’ We may joke and make memes about how we act when we are hungry, but it’s been in a verifiable truth: you are, in fact, what you eat. The food we consume what food does to our bodies impacts our behaviour. Criminologists in particular have been interested in the role that malnutrition has on childhood behaviour.

Two major patterns stand out. The first is the role that omega-3 fatty acids have on reducing behaviour. Omega-3 fatty acids are known as the “healthy fat” and are typically found in seafood, seeds and nuts. In a study where children were randomly assigned to receive omega-3 supplementation versus not supplements, caretakers reported that children who received the reduced disruptive behaviours 6 months later (Raine et al., 2015). A large-scale meta-analysis[2] showed that omega-3 fatty acid consumption is associated with reduced aggression (Gajos & Beaver, 2016). So eat your mackerel!

Horse mackrel 500 yen by Timothy Takemoto is licensed under CC-BY-NC 2.0

But the relationship between nutrition and aggression isn’t limited to omega-3 fatty acids. Malnutrition in general has been found to be associated with increased antisocial behaviour in preschoolers (Jackson, 2016) and adolescents (Galler et al., 2012). An important factor in this connection is to look more closely into why young people are malnourished to begin with. Food insecurity is a real problem in many parts of the world, including Australia. Families experiencing food insecurity are more likely to experience malnutrition, which is then linked to childhood misconduct and delinquency (Jackson & Vaughn, 2017). As you can see, this is the interplay between biology (nutrition) and sociology (access to quality food).

Genetics and Crime

No chapter on biosocial criminology would be complete with a discussion of the role of genetics in understanding aggression and criminality. First and foremost, there is no crime gene. As we have seen in Chapter 2, crime is inherently a social construct. Therefore, most research into genetics and crime focuses on aggressive behaviour. And studies of genetic relationships to aggression remain controversial, due to the historical connections with the study of eugenics and unethical research of the early and mid-twentieth century.

Genetic research has studied twins or siblings in an attempt to understand the role of heredity on behaviour. The most famous studies of genetics and crime are twin studies. The most controversial were adoption studies, where twins were separated into different homes in order to determine the role of nature versus nurture. But many other studies looked for similarity in behaviours between family members. The most common finding is that self-control appears to be, in part, inherited (see Chapter 9 for more discussion on self-control control) (Schwartz et al., 2017).

There have also been advancements in how we have studied the contribution of genetic influences to behaviour. Much of this improved understanding comes from the field of epigenetics. Epigenetics is the study of how genes change expression, depending on our environment. Changes to people’s diet or exposure to different group membership may influence when genes are ‘switched on’ or left untouched (Wortley, 2011). For example, a person maybe prone to addiction but without exposure to drug use, the potential to become addicted is never realised. Conversely, the influence of drug users in friendship groups may cause a person with addictive personality traits to become easily addicted. The long and short of it is that nature and nurture interact to influence our development (Moffitt, 2005).

Mental Health and The Criminal Justice System

The link between mental health and the criminal justice system is an important connection that draws significant attention from researchers. In this text, three research papers conducted within Australia will be discussed. These studies examine how mental health affects reoffending risks, incarceration rate and the overrepresentation of Indigenous Peoples in the criminal justice system. These findings are significant as they emphasise the need for further research, practical interventions and additional support systems that address mental health disorders for vulnerable individuals.

The research article titled Psychiatric illness and the risk of reoffending: recurrent event analysis for an Australian birth cohort by Ogilvie et al. (2021) is the first focus of this discussion. This paper was sampled from the 1983 to 1984 Queensland birth cohort, consisting of 83,362 individuals (48.5% female, 51.5% male) and 4,821 Indigenous Peoples (5.8%). The findings revealed that individuals with psychiatric illnesses were more susceptible to engaging in repeated criminal behaviour. Individuals with a psychiatric diagnosis reoffended 73.1% of the time, compared to 56% for individuals without a condition. Reappearances of people with a psychiatric diagnosis in court occurred in violent (20.5 vs. 8.5%), nonviolent (60.3 vs. 40.3%) and other minor (61.7 vs. 44.1%) offences compared to those without a psychiatric diagnosis. This study shows that more frequent criminal contact could exacerbate psychiatric illnesses, potentially creating further offending risks, demonstrating the critical necessity of addressing mental health concerns within the criminal justice system to break the reoffending cycle and foster better outcomes for those involved.

The second paper is titled Lifetime prevalence of mental illness and incarceration: An analysis by gender and Indigenous status by Stewart et al. (2020). This study sampled individuals with a 1990 birthdate and found a concerning overrepresentation of individuals with mental health issues among the incarcerated population, with a notably disproportionate impact on Indigenous Peoples and women. Among the individuals sentenced to custody, one-third had a mental health diagnosis, in contrast to only 6.1% of the total birth cohort population. Indigenous Peoples with a mental health diagnosis were 6.14 times more prone to receiving a custodial sentence than non-Indigenous individuals with a mental health diagnosis. Similarly, females with a mental health diagnosis were 5.49 times more likely to receive a custodial sentence than males with a mental health diagnosis. Identifying these vulnerable groups has revealed an urgent need for targeted interventions and culturally sensitive mental health support within the criminal justice system.

The last journal article that will be discussed is titled Psychiatric disorders and offending in an Australian birth cohort: Overrepresentation in the health and criminal justice systems for Indigenous Australians by Ogilvie et al. (2021). This study explored the overlap between mental health and offending, focusing on Indigenous Peoples. Similarly, this study examined a population-based birth cohort of individuals born in Queensland in 1990. Of the individuals with a psychiatric illness diagnosis, 53.0% also had a proven offence; this being much higher for Indigenous Peoples, with the statistic being 80.5% compared to 47.0% for non-Indigenous Peoples. By 23/24, 16.2% of Indigenous Peoples with a proven offence had also received a substance use disorder diagnosis, compared with 7.8% of non-Indigenous Peoples. Indigenous Peoples with a diagnosed disorder were also most likely to have more than five proven offences (39.2% vs. 3.3%). These statistics show the extreme over-representation of Indigenous Peoples with mental health diagnoses who have had contact with the criminal justice system. It demonstrates that a psychiatric diagnosis could increase the risk of earlier and more frequent criminal justice contact, emphasising that Indigenous Peoples with a psychiatric disorder are a highly vulnerable group.

Overall, these findings highlight the significant overlap between mental health issues and the criminal justice system. The research advocates for expanding culturally appropriate mental health interventions, particularly within substance use disorders. Additionally, it supports the idea that early diversion and intervention during initial contact with the criminal justice system could be an effective strategy to prevent future reoffending into adulthood for vulnerable people. This research and understanding of how mental health and the criminal justice system intersect are vital to paving the way for more compassionate and successful approaches to supporting vulnerable individuals and reducing the cycle of reoffending.

A summary by Chole Veerman

Traumatic Brain Injury

A traumatic brain injury (TBI) is an injury of the brain that occurs as the result of a physical impact to the head or body. Causes are diverse but can include falls, car accidents and assaults. Even sports can lead to TBI. It is estimated that up to 200,000 TBI occur in Australia each year, but many are unreported or undiagnosed. In recent years, criminologists have realised that TBI can affect behaviour and may increase violence and aggression, as well as have other negative life consequences. One research study collected information from a group of high risk justice involved young people in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania (USA) and Phoenix, Arizona (USA). Youth who experienced a TBI had higher levels of delinquency, bullying, and impulsivity (a trait commonly associated with low self-control) (Silver et al., 2020).

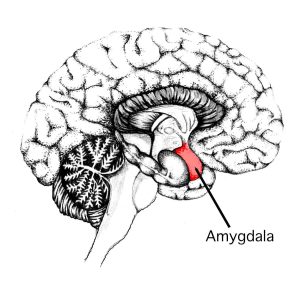

Because individuals can obtain a TBI in ways that are not related to criminal activity, like sports, there is still a lot we do not know about TBI in justice involved populations. Certainly, the type of brain injury will affect the types of behavioural outcomes that could happen. We are learning more about the functions of the brain through advancements in technology that allows us to view the structure of the brain. Using technology such as fMRIs (Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging), researchers have identified the parts of the brain that may be related to antisocial behaviour. The amygdala is a region of interest (Kaya et al, 2020). The amygdalae are small almond shaped brain structures on either side of the brain hemisphere that help regulate emotion, including fear. Research suggests that individuals with smaller amygdalae are more likely to engage in antisocial behaviour (Kleine Deters et al., 2022). Whether due to biology or injury, brain structure appears to matter. This is an area where we can continue to expect major contributions to our understanding of criminality in the near future.

Amygdala is licensed under CC0 1.0 Universal Public Domain Dedication

THEORY CRITICISMS

In addition to the criticisms already raised in relation to the application of biosocial theory on race and the previously poor ethical practices, many criminologists object to ideological elements that underpin this theoretical approach (Walsh & Wright, 2015). These criticisms relate to determinism, reductionism, and the nature of socially constructed crime. Many argue that a biosocial approach to understanding crime is too deterministic and does not give enough credit to individual decision making. When genes or brain functions are linked to criminality, how do we separate out those who exhibit the trait but do not engage in criminal behaviour?

Similarly, critics of biosocial approaches argue that they are reductive, or overly simplify diverse human behaviour rather than recognising the intense interplay of the environment and social influences (Heylen et al., 2015). For instance, aggressive behaviour may be linked to genes, whereas in reality, the potential for aggression may not be realised unless certain environmental or situational factors are present, such as peer pressure or the presence of an antagonist.

Finally, crime is, and always has been, social (Walsh & Wright, 2015). For instance, consuming alcohol in Dubai is illegal without a permit, whereas it is unregulated for people over the age of 17 in Australia. Similarly, using cannabis is illegal in 25 of the 50 American states, with another 14 legalising medicinal cannabis (Tyko, 2023), and Australia looks like it is headed in that direction. The social construction of crime means that anything considered legal is ignored in research analyses, leaving some important political, social, or environmental factors unconsidered.

THE FUTURE OF THE THEORY

The findings from multifactorial studies with a biosocial focus have helped shape our responses within the criminal justice system and provided new ways to envision prevention and rehabilitations. A better understanding of the diverse causes of criminality brings with it the opportunity to improve outdated systems and incorporate innovative new approaches. Newsome and Cullen (2017) provide an example of this improvement when they updated the ‘risks, needs and responsivity model’ used within criminal rehabilitation. By incorporating biosocial factors like genetics, neurobiology, physiology and nutrition into the existing model of understanding behaviour, neurological and physiological assessments can improve current risk assessments. By continuing to focus on biosocial research elements relating to crime, further improvements to criminal justice system responses will continue to emerge.

The application of biosocial desistance models has moved from understanding young people to better supporting adults, especially with what we have learned about brain structure and function (Boisvert, 2021). Through neuropsychological functioning studies, we have learned that incarcerating low-risk individuals is more likely to induce stress system responses which will impact future brain development, indicating imprisonment should be used as a last resort only. Other research on brain development also shows that high-risk individuals who are incarcerated may benefit from programs to minimise diminished cognitive functioning, such as increased sleep time and limited time in solitary confinement. These changes involve identifying genetic risk factors, understanding the impact of exposure to criminogenic environments within dynamic and static needs assessments, and including a range of cognitive-based treatments in criminal justice responses (Boisvert, 2012).

A Note about Biosocial Criminology and Race

Biosocial theory has previously been used to explain the social and biological ways we understand racial groups (Larregue & Rollins, 2019). However, critics are cautious when applying biosociology to race because of the tendency of some researchers to link criminality to minority populations, such as Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. Doing so actively ignores the fact that race is a social construct and reducing people to their race ignores important structural, community, intergenerational and social differences in how people experience their identify. Larregue & Rollins (2019) argue it is impossible to control for race in research as it does not capture the complexities of social relationships and practices. Any attempts to do so are likely to led to racist outcomes such as colour-blind interpretation, or researchers erring towards blaming races for an increased risk in criminality. This is principally problematic considering the social construction of race and diversity within cultures.

The same is true for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. With more than 500 communities living in Australia and surrounding islands, they are not a homogenous group (Evolve Communities). Trying to account for the differences in traditions and practices between these communities is unrealistic in single studies comparing differences between non-Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities. For example, there are differences in languages, laws, belief systems and relationships within these 500 communities. Failure to recognise these differences has led to criticisms of Pan-Aboriginalism in Australia; the failure to recognise the uniqueness of hundreds of communities and the tendency to attribute similar characteristics to all communities broadly.

Research conducted by Larregue & Rollins (2019) shows the problematic nature of applying race within biosociology. They reviewed 107 studies exploring biosocial criminality and found race was comprehensively studied in only three of the 107 studies. However, even in these few cases, researchers failed to look at the ‘effects of race’ and criminality, for instance the social mechanisms contributing to and influencing racial populations in set societies. Therefore, it is not possible to truly apply biosocial theory to the many Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities. However, the theory does have other application uses mainly relating to the criminal justice system.

For more information about how people understand race and racial identify, the National Human Genome Institute at the US National Institutes of Health is a good place to start. Australia is more likely to use the terms ethnicity and indigeneity to describe individuals who are part of distinct cultures within our communities (Kowal & Watt, 2018). To many, biological constructions of ‘race’ ignore the realities of shared culture and social status as being an important part of identifying with a community. While new discoveries come every day, the field of genomics is still quite new and it requires us to be critical of findings that separate people into categories that are not supported by science or sociology.

CONCLUSION

Biosocial theory is an interdisciplinary framework for evaluating human behaviours, including aggression and criminality. The intersection between biological and environmental influences remains an important part of contemporary criminological research. While the theory has not always been favoured in the scientific community, the application of more ethical practices, combined with more advanced technology, has increased interest and improved our knowledge about how to adapt prevention, intervention, and rehabilitation efforts.

Check Your Knowledge

Discussion Questions

- Define biosocial theory in the context of criminality and discuss how it integrates biological and social factors to explain criminal behaviour. Provide examples to illustrate the key concepts of biosocial theory and its application to understanding crime.

- Consider the practical applications of biosocial theory in the development of interventions and prevention strategies. Reflect on how a better understanding of the biological and social factors contributing to criminal behaviour can inform targeted interventions. How might this knowledge be used to identify at-risk individuals early on and implement effective preventative measures?

- Explore the ethical considerations associated with applying biosocial theories to criminality research. Discuss potential implications for stigmatization, discrimination, and the broader societal impact. How can researchers ensure cultural sensitivity and ethical conduct when studying the biosocial aspects of criminal behaviour.

REFERENCES

Barkow, J. H., Cosmides, L., & Tooby, J. (Eds.). (1995). The adapted mind: evolutionary psychology and the generation of culture. Oxford University Press.

Barnes, J. C., Boutwell, B. B., & Beaver, K. M. (2015). Contemporary biosocial criminology: A systematic review of the literature, 2000–2012. The handbook of criminological theory, 75-99.

Bedoya, A., & Portnoy, J. (2023). Biosocial criminology: History, theory, research evidence, and policy. Victims & Offenders, 18(8), 1599-1629.

Berryessa, C. M., & Cho, M. K. (2013). Ethical, legal, social, and policy implications of behavioral genetics. Annual Review of Genomics and Human Genetics, 14, 515-534.

Boisvert, D. L. (2021). Biosocial factors and their influence on desistance. NCJ 301499, in Desistance From crime: Implications for research, policy, and practice (Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice, National Institute of Justice, 2021), NCJ 301497. https://www.ojp.gov/pdffiles1/nij/301499.pdf

Brennan, P. A., & Raine, A. (1997). Biosocial bases of antisocial behavior: Psychophysiological, neurological, and cognitive factors. Clinical psychology review, 17(6), 589-604.

Burgess, R. L., & Draper, P. (1989). The explanation of family violence: The role of biological, behavioral, and cultural selection. Crime and Justice, 11, 59-116.

Fraga, M. F., Ballestar, E., Paz, M. F., Ropero, S., Setien, F., Ballestar, M. L., … & Esteller, M. (2005). Epigenetic differences arise during the lifetime of monozygotic twins. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 102(30), 10604-10609.

Gajos, J. M., & Beaver, K. M. (2016). The effect of fatty acids on aggression: A meta-analysis. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 69, 147–158. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2016.07.017

Galler, J. R., Bryce, C. P., Waber, D. P., Hock, R. S., Harrison, R., Eaglesfield, G. D., & Fitzmaurice, G. (2012). Infant malnutrition predicts conduct problems in adolescents. Nutritional Neuroscience, 15(4), 186–192. https://doi.org/10.1179/1476830512Y.0000000012

Green, C. D. (1997). The principles of psychology William James (1890). Classics in the history of psychology.

Heylen, B., Pauwels, L. J., Beaver, K. M., & Ruffinengo, M. (2015). Defending biosocial criminology: On the discursive style of our critics, the separation of ideology and science, and a biologically informed defense of fundamental values. Journal of Theoretical & Philosophical Criminology, 7(1), 83.

Jackson, D. B. (2016). The link between poor quality nutrition and childhood antisocial behavior: A genetically informative analysis. Journal of Criminal Justice, 44, 13–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrimjus.2015.11.007J

Kaya, S., Yildirim, H., & Atmaca, M. (2020). Reduced hippocampus and amygdala volumes in antisocial personality disorder. Journal of Clinical Neuroscience, 75, 199–203. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jocn.2020.01.048

Kleine Deters, R., Ruisch, I. H., Faraone, S. V., Hartman, C. A., Luman, M., Franke, B., Oosterlaan, J., Buitelaar, J. K., Naaijen, J., Dietrich, A., & Hoekstra, P. J. (2022). Polygenic risk scores for antisocial behavior in relation to amygdala morphology across an attention deficit hyperactivity disorder case-control sample with and without disruptive behavior. European Neuropsychopharmacology, 62, 63–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euroneuro.2022.07.182

Kowal, E., & Watt, K. (2018) What is race in Australia? Journal of Anthropological Studies, 96, 229-237. https://www.isita-org.com/jass/Contents/2018vol96/Kowal/30640719.pdf

Larregue, J., & Rollins, O. (2019). Biosocial criminology and the mismeasure of race. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 42(12), 1990-2007.

Moffitt, T. E. (2005). The new look of behavioral genetics in developmental psychopathology: Gene-environment interplay in antisocial behaviors. Psychological Bulletin, 131(4), 533–554. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.131.4.533

Newsome, J., & Cullen, F. T. (2017). The risk-need-responsivity model revisited: Using biosocial criminology to enhance offender rehabilitation. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 44(8), 1030- 1049.

Raine, A. (2002). The biological basis of crime. Crime: Public policies for crime control, 43, 74.

Raine, A., Portnoy, J., Liu, J., Mahoomed, T., & Hibbeln, J. (2015). Reduction in behavior problems with omega-3 supplementation in children aged 8-16 years: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, stratified, parallel-grouptrial. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines, 56(5), 509–520.

Rocque, M., Welsh, B. C., & Raine, A. (2012). Biosocial criminology and modern crime prevention. Journal of Criminal Justice, 40(4), 306-312.

Schwartz, J. A., Connolly, E. J., Nedelec, J. L., & Beaver, K. M. (2017). An investigation of genetic and environmental influences across the distribution of self-control. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 44(9), 1163–1182. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093854817709495

Silver, I. A., Province, K., & Nedelec, J. L. (2020). Self-reported traumatic brain injury during key developmental stages: Examining its effect on co-occurring psychological symptoms in an adjudicated sample. Brain Injury, 34(3), 375–384. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699052.2020.1723166

Tyko, K. (2023). Where is marijuana legal – and illegal – 2023. AXIOS. https://www.axios.com/2023/04/20/weed-pot-april-20-medical-marijuana-legal#

Tremblay, R. E., Hartup, W. W., & Archer, J. (Eds.). (2005). Developmental origins of aggression. Guilford Press.

Jackson, D. B., & Vaughn, M. G. (2017). Household food insecurity during childhood and adolescent misconduct. Preventive Medicine, 96, 113–117. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2016.12.042

Walsh, A., & Wright, J. P. (2015). Biosocial criminology and its discontents: A critical realist philosophical analysis. Criminal Justice Studies, 28(1), 124-140.

Wortley, R. (2011). Psychological criminology: An integrative approach (Vol. 9). Taylor & Francis.

- Spoiler alert: the bumps in your head do not predict your personality. No matter what you saw on TV. But if you want to know about phrenology, check out this article published in the journal Cortex. ↵

- A meta-analysis is a study that takes information from all existing studies on one topic and comes to a conclusion about what the totality of the evidence says. It is very useful when there are a lot of studies and it can be difficult to keep track of which one is the most recent or the best done. This way, all of the research is put together to make an overall stronger conclusion. ↵

an approach to society that relies on empirical evidence and observation, often including experiments and other similar methdologies

a statistical study that combines findings from several independent studies on the same subject, in order to determine the totality of the evidence