14 What Happens Next? Criminal Justice Responses

Troy J. Allard

Learning Objectives

- Understand why the criminal justice system has authority over individuals and their behaviour.

- Learn about the three main components of the criminal justice system – police, courts and corrections – and begin to explore how they are interconnected.

- Become familiar with some of the most pressing issues in Australian criminal justice today.

Before You Begin

- Have you ever thought about why you let a police officer stop you or pull you over? Why do we listen to individuals in uniforms? What do we get out of it?

- Do you know anyone who has been a victim of a crime? Did they report it to the police? Why or why not?

- What problems in criminal justice do you think are the most important? Do you think everyone would agree with you? Why?

INTRODUCTION

This chapter provides an overview of the basis, operation and effectiveness of the criminal justice system. First, it outlines the authority and theoretical underpinnings of how the criminal justice system is able to act in the ways that it does. Then, it describes the goals of the criminal justice system and each of the main components – police, courts and corrections. We outline the basic structure of the system and detail the ways that a crime is typically handed. We also discuss the indicators that are used to help assess the performance and efficiency of the criminal justice system and its main components. The chapter concludes by providing a description of five key issues in criminal justice today: 1) public confidence; 2) the media and politics; 3) system coordination and national frameworks; 4) youth justice and the minimum age of criminal responsibility; and 5) attrition.

Authority and Theoretical Underpinnings

Criminal justice system’ are used around the world as a way for societies to promote social order and to respond to crime. In liberal democracies like Australia, the legitimacy and authority of the system rests on the social contract. The social contract is the general and/or widespread consensus by community members about the rules that need to be followed for peaceful coexistence, and to stay peaceful, community members each give up some freedoms or rights in return for safety. When these rules are broken, the government can use the criminal justice system to deal with the alleged wrongdoer.

The power and authority of the government to respond using the criminal justice system is derived the constitution and from liberal democratic processes. Sections 51 and 52 of the Australian Constitution outline Commonwealth and State responsibilities, with the Commonwealth government able to make laws with respect to “peace, order and good government of the Commonwealth with respect to” several specific matters, including defence and external affairs. While not explicitly listed in Section 52 as a State responsibility, the power to enforce criminal laws is generally considered a state responsibility based on historical and legal traditions.

In practice, governments derive their authority to enforce criminal law through legislation and the legitimacy of the criminal justice system is reinforced by government accountability mechanisms. Governments are elected to represent voters and can therefore amend, change, and have legislation enforced on their behalf, until they have to answer to the voting public in the next election. Each state and territory (by delegation from the Commonwealth) in Australia has its own criminal code and laws, which cover a wide range of offences and prescribe the powers and responsibilities of law enforcement agencies within the respective state or territory. Each state’s criminal code establishes police and other agencies to investigate and enforce criminal laws in accordance with their legislative frameworks. Therefore, there are nine ‘criminal justice systems’ in Australia – the six states, two territories and Commonwealth. It should be noted, of course, that laws and regulations are constantly updated, and often at the bestow of special interest groups – meaning that the public may have little real input into laws and how the system operates.

Criminal Justice and Sentencing

While each state and territory have their own ‘criminal justice system’, they have similar principles and overarching goals, as outlined in legislation such as Penalties and Sentences Acts. These Acts outline the goals of sentencing and factors that judges and magistrates must consider. These goals include:

Retribution or punishment of wrongdoing by imposing penalties on offenders as ‘pay-back’ that are proportionate to the seriousness of the crime committed.

Deterrence of individuals from engaging in criminal behaviour, through general deterrence by discouraging others in the community from committing similar offences, as well as specific deterrence which aims to discourage the individual offender from reoffending.

Rehabilitation by addressing the underlying causes of criminal behaviour and helping offenders reintegrate into society as law-abiding citizens. Sentencing may involve the provision of rehabilitation programs, counselling, or other interventions that aim to reduce future offending such as substance abuse interventions, education and employment programs.

Restitution and reparation for harm caused so that the offender takes responsibility for their actions, including fines, community service and other forms of restitution.

Incapacitation prevents future offending by restricting someone who has previously offended such as through imprisonment, home detention, or electronic monitoring.

Goals of the Main Components

While there is no criminal justice system as an actual unit, the term is used to refer to three independent but interrelated components that are the investigative (police), adjudicative (courts), and the correctional (corrections) arms (Hawkins, Biles & Wilson, 1970). These separate components are weakly bound together as they are mutually dependent on each other for information. Decisions in one part of the system can also affect the other parts of the system in several different – and often unexpected – ways (Ashworth, 1994; Travis, 1990; Sallman & Willis, 1984). The components of the criminal justice system have no core organisation, which often results in a lack of organised and interrelated conditions and directives (Anderson & Newman, 1993; Ellis, 1993). The three arms of the criminal justice system are very different, have different policies and have specific and distinct goals (Bryett et al., 1993).

The three components of the system are designed to give effect to the principle of the separation of powers. The separation of powers ensures that one group does not hold a monopoly of power and become ‘judge, jury and executioner.’ For instance, the courts review evidence to ensure that police follow appropriate procedures and practices; this relationship is necessarily (at least in part) adversarial in nature. This helps prevent miscarriages of justice that may arise due to police adopting poor practices, bias and/or corruption, or unduly pressuring the prosecutor to pursue (or drop) any charges. Undue political influence on specific cases is preventing by the operational heads of departments (such as police services, departments of justice and attorney general and corrections) being appointed, rather than being elected.

The investigative arm has the broad goal of preserving public order, investigating breaches of the criminal law and bringing alleged offenders before the adjudicative arm (the courts), as well as improving road safety and assisting the judicial processes (Bryett et al., 1993; Productivity Commission, 2023). Other frequently identified goals of the investigative arm include protecting the community, providing emergency assistance and preventing and deterring crime, such as through community policing (Prenzler & Sarre, 2020). Police spend less than one-third of their time responding to and managing crime, principally offences such as domestic and family violence (Brisbane Times, 2021). Instead, police will spend most of their time adopting a supportive social role that goes well beyond law enforcement and crime control.

The adjudicative arm has the task of determining the guilt or innocence of people charged by the investigative arm with offences and has the goal of choosing the appropriate penalty of people found guilty (Bryett et al., 1993; Productivity Commission, 2023). Key overarching goals of the adjudicative arm include being open and accessible, affordable and progressing matters to a high standard, expeditiously and in a timely manner (Productivity Commission, 2023). The adjudicative arm promotes fair and just outcomes, with safeguards built into the system to help ensure that innocent people are not found guilty for crimes they did not commit (e.g., right to silence, natural justice, legal representation, rules of evidence). Appropriate penalties are determined based on the individual circumstances of each case such as the offence severity, criminal history of the offender and aggravating/mitigating factors – and how these feed into and relate to the key goals of sentencing examined earlier – retribution, deterrence, rehabilitation, restitution and/or community safety/incapacitation.

The correctional arm includes community correction systems and prisons and is tasked with carrying out the penalties imposed by the adjudicative arm and parole boards. This involves managing and supervising individuals who are incarcerated in custodial institutions or subject to community-based orders and providing programs and services that aim to address the different reasons that individuals may offend (Bryett et al., 1993; Productivity Commission, 2023). According to the Productivity Commission (2023, p. 91), the three goals of corrective services are: 1) to provide “a safe, secure and humane custodial environment; 2) appropriate management of community corrections orders and programs and services that address the causes of offending, maximise the changes of successful reintegration into the community; and 3) encourage offenders to adopt a law abiding ways of life.”

Structure and Operation of the Criminal Justice System

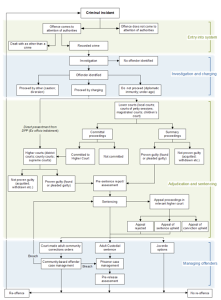

The basic process that is followed by the system when there is a criminal incident is outlined in Figure 15.1. Once a crime comes to the attention of authorities, it progresses to the investigative arm if detected and/or reported and a decision is made that an alleged crime has occurred. Once this decision is made, the incident is progressed through the formal criminal justice system.

Source: Flows through the Criminal Justice System by The Steering Committee for the Review of Government Service Provision is licensed under CC-BY 4.0 (Productivity Commission, 2023)

The police are organised with general duties or patrol officers responsible for responding to calls for service and generally being first responders to crime scenes, where they may collect evidence and for more serious offences preserve the crime scene and collect evidence.

Detectives conduct investigations and collect evidence, initiating formal responses where required and initiate prosecutions.

Watch Leanne discuss this research and her findings. Video Transcript [Microsoft Word].

In cases where police have no further leads and need new information, they may use non-traditional techniques to keep investigations moving forward, including mediums who claim to communicate with the deceased. Many high-profile/unsolved homicides attract mediums who profess to be able to divine for information about the deceased, perpetrator or case and submit details to detectives for follow-up as new “evidence”. Research in this area will build evidence-based knowledge about the usefulness of mediums for police investigations and helping families of victims of homicide gain some closure.

Semi-structured interviews were conducted with 10 mediums that had expertise in communicating with and bringing through information from deceased loved ones and experience in gathering information to support police and/or family members with homicide investigations. An interview guide was used in interviews which were conducted online and took 45 minutes to 1 hour. A nonprobability convenience sample was used, with mediums identified (selected for convenience) as meeting the sampling criteria and/or through “expert recommendations”.

This research identified for the first-time mediums’ four-stage process when working on homicide cases:

- 1) Prepare for case: Physically, mentally, emotionally and energetically prepare, ensure physical environment is safe, begin ‘connecting in’ and communicating information from the deceased victim;

- 2) Initial information collection: Identify the victim, how they were killed and where they died (scene) to confirm they are connected to the ‘correct’ deceased victim and/or case;

- 3) In-depth collection of details: Further details about the circumstances of the case and potential witnesses and/or suspects;

- 4) Close the case: Thank the deceased victim for communicating information about the case.

By identifying and understanding mediums’ four-stage processes when working on homicide cases, we could compare this with police processes when investigating homicides and found overlaps in critical tasks performed by mediums and police when collecting and reporting information/evidence about homicide cases in three areas:

- 1) focus of the investigation

- 2) information gathering and

- 3) use of intuition.

An understanding of these processes can help homicide detectives in cases where they need new leads, ideas and fresh new approaches to be able to work with mediums more effectively and keep investigations moving forward. This and the current research examining medium’s ability to report accurate information against real homicide cases will make an important and innovative contribution to the literature about the use of mediums to support homicide investigations, could lead to the discovery of new evidence to assist with investigations and provide families of victims with some closure or justice.

This research suggests that there is a clear process used by mediums when working on homicide cases and provides a foundation from which we can learn more about the how mediums could effectively work with police as an additional tool to support them with homicide investigations.

Specialist squads provide services to assist the process. For example, the dog squad can be called to trace a fleeing suspect, or forensic services to collect and test evidence. Forensic services may be used to help investigate or prove an offence and is typically used for illicit drug offences, unlawful entry and theft offences. Homicide, abduction/harassment and sexual offence cases are most likely to make extensive use of forensics (see Allard, McCarthy & Stewart, 2020). Intelligence and covert services may collect background information on persons of interest and evidence to assist investigations and prosecutions. Likewise, the drugs and serious crimes group and fraud and cybercrime group may be called on to provide the expertise needed if required by specific investigations.

Criminal intelligence is an inextricable component of contemporary law enforcement. Despite the integrity of a criminal intelligence capability, limited research has been undertaken to develop frameworks for strategic criminal intelligence, particularly in relation to the transnational serious and organised crime environment. The consequences of these circumstances are that intelligence practitioners are experiencing a lack of guidance and have been positioned to rely on ill-fitting approaches to intelligence tasks.

The elements precipitating this knowledge gap include the traditional placement of ‘Intelligence’ as a theoretic paradigm within the academic disciplines of Political Science and International Relations and, limited acknowledgement of nuances between police typologies, specifically between the dominant Community Policing in contrast with police practice in de-localised transnational serious and organised crime operating environments.

Through the adoption of a qualitative thematic analysis methodology, this research interrogated existing academic literature as well as publicly accessible intelligence products from Five Eyes Law Enforcement Group (FELEG)[1] agencies operating in the transnational serious and organised crime environment to compare and contrast an agency’s strategic objectives as well as their approach to intelligence collection, analysis and production.

The coalescence of theoretical academic literature and real-world police practice that this method fostered, enabled the identification of shared agency objectives, common collection requirements and analytic perspectives that could be used to create a theoretic model for strategic criminal intelligence production that is consistent with the phases of the Intelligence Cycle.

The final element of the research, following identification of the intelligence requirements and formulation of the theoretic model, known as the GEOFAC Model, was a viability test using two case studies to test the applicability and adaptability of the model in real-world, diverse policing scenarios.

A review of academic literature revealed bolstered assertions that there was an absence of fit-for-purpose strategic criminal intelligence frameworks for the transnational serious and organised crime operating environment; however, it did highlight meaningful analytic perspectives that complement and enhance real-world strategic criminal intelligence approaches.

Analysis FELEG agency reporting revealed three common strategic ambitions shared by FELEG agencies in the transnational serious and organised crime environment:

- Enforcement of the Law

- Harm Reduction

- Proactive Policing

These agency objectives informed the development of the GEOFAC Model, which identified five core ‘Collection Elements’ and six ‘Analysis Vectors’ that were tailored to enable intelligence practitioners to deliver intelligence outputs that suit FELEG’s strategic aims.

Testing of the theoretic model on real-world transnational serious and organised crime events revealed the adaptability of the model across crime types and geographic contexts and hence, its real-world applicability.

This research served the dual function of addressing an academic knowledge gap as well as providing real-world value through the development of a testable, applicable and adaptable theoretic framework for the production of strategic criminal intelligence analysis in the transnational serious and organised crime operating environment, that was informed by both academia and practice.

Despite the successful application of the GEOFAC Model against real-word policing challenges, the research was limited by a reliance on open source FELEG intelligence products and a disconnect from direct law enforcement input. It is recommended that further research be undertaken in collaboration with law enforcement agencies operating in the transnational serious and organised crime environment to build upon the findings of this thesis for the purposes of enhancing and refining a theoretic model for strategic criminal intelligence.

Criminal intelligence will almost certainly remain a staple of modern police practice; however, failure to mitigate the use of inadequate and dissonant models for strategic criminal intelligence jeopardises the effectiveness of criminal intelligence as a tool to inform and influence law enforcement priorities.

This research endeavoured to reduce this research gap my melding the insights of academia and practice to identify the unique requirements of strategic criminal intelligence in the transnational serious and organised crime operating environment and, incorporate them into an applicable and comprehensive strategic model.

In doing so, this research has considered the nuances and variations in police typologies and has developed deeper understandings as to strategic criminal intelligence requirements. It is both intended and hoped that this research can add practical value to law enforcement and criminal intelligence practitioners.

Matters are brought before the lower court (e.g., Magistrates) by police prosecutors, with more serious matters transferred to the independent Director of Public Prosecutions and a committal hearing held in the lower court to determine if there is sufficient evidence to progress to trail in the higher (e.g., District and Supreme) courts.

The criminal courts hear guilty pleas and sentence, and where matters are contested, they adjudicate cases brought before them before sentencing those found guilty. They hear cases brought before them based on legislation and common law precedent, which is the notion that current cases should be treated the same as previous cases unless there is or are distinguishing factors. Other important features of courts include that they have consistent, predictable, clear and certain rules and practices, with individuals having the right to a fair hearing and legal representation (Sallman & Willis, 1993). If found guilty, the courts apply their considerable discretion and consider the circumstances of the case, weighing the relevant sentencing goals to determine an appropriate and suitable sentence.

Matters may be diverted to specialist courts, which have developed as our understanding about the causes of crime has improved, including drug courts, mental health courts and Indigenous courts; as well as youth courts which have exited for over a century to respond to offending by those aged 10 to 17 inclusive.

Corrective services administers the sentences of the courts and has two major components, custodial and community corrections. In custodial corrections, prisoners supposed to be held securely and humanely. In community corrections, offenders are supervised on probation or parole or some other form of community supervision, such as intensive corrections orders. In community corrections, there are several conditions placed on individuals in order to try to prevent illegal behaviour, such reporting requirements, random testing for illicit drugs and specialised programs to reduce specific risks.

Performance and Effectiveness

The overarching goals of the criminal justice system are supposed to be based on broader goals of humanity and fairness (Sallman & Willis, 1984) and align with those of the Australian liberal democratic society, including balancing freedoms while maintaining social order, fairness and unbiased decision-making, openness, accountability, and efficiency. Because criminal justice systems have great reach and can significantly impact the lives of Australians, these broader goals should be a concern for all Australians and the components of criminal justice systems should always be striving for excellence.

While there are some differences between the ‘criminal justice systems’ that operate in Australia, operation and performance can be assessed using indicators derived from the Report on Government Services (Productivity Commission, 2023). Total expenditure on justice services was $22 billion in 2021-2022, with policing agencies and correctional agencies accounting for the largest proportions of expenditure (65% and 26% respectively, Productivity Commission, 2023). When overall cost is disaggregated based on the total population, an estimated $854 is spent per person, per year to operate the Australian justice system. This can be used as a measure of efficiency, which can be compared across jurisdictions (States/Territories) or over time to assess how the criminal justice system is performing. This can be compared to other government expenditures on social security and welfare ($227 billion, $9010 per person, AIHW, 2023a), health ($241 billion or $9365 per person, AIHW, 2023b), or the cost of defence ($44 billion, $1708 per person, Australia Strategic Policy Institute, 2021).

Sector wide measures of performance include the number of time people are proceeded against by police, or the number of crimes expressed as a rate (see Chapter 2 for a reminder of how to calculate a rate) given the number of people in the population and reoffending rates. In Queensland, 66.9% of offenders were proceeded against by police in the past 12 months 2021-2022, with fewer having 2 (17%), 3 (7.1%), 4 (3.1%) or 5 procedures (5.5%) (Productivity Commission, 2023). After release from prison, 42.4% of prisoners who are released from prison and 16.4% of offenders who complete community-based orders like probation and parole return to a new corrective services sanction within two years (Productivity Commission, 2023).

Measures used by the Productivity Commission (2023) to assess the performance of the police relate to: workforce representation, road safety, deaths in police custody, persons found guilty in Magistrates court, community satisfaction, perceptions of safety, perceptions of police integrity, complaints, youth diversions and outcomes of investigations, expenditure per person and crime victimisation (based on surveys examining reported experiences over the past 12 months). These surveys show that nationally there were approximately: 2,032 victims of assault, 536 victims of sexual assault and 267 victims of robbery per 100,000 people (Productivity Commission, 2023).

A range of measures are also used to assess the effectiveness of the courts, relating to both access (timeliness and delay and affordability) and quality (complaints). Measures of efficiency include: Judicial officers per finalisation, FTE[2] staff per finalisation and Cost per finalisation. The cost per finalised case in court during 2021-2022 depended on which court processed the matter: $25,292 in the supreme courts, $16,331 in district/county courts, and $914 in the magistrates and children’s courts.

Measures used to assess the effectiveness of custodial corrections relate to the proper treatment of prisoners (e.g., offence related programs, education and training, prisoner employment, time out of cells, community work, and prison utilisation) as well as the quality of treatment (unnatural deaths and assaults in custody). The effectiveness of community-based orders are assessed by examining the proportion of orders successfully completed. Measures of efficiency relate to the cost per individual incarcerated or under supervision per day. In 2021-2022, it cost an average of $405.18 per individual per day in custody, or $28.65 per individual per day under community-based supervision.

SELECTED ISSUES AND PROBLEMS

Public Confidence, The Media and Politics

Public confidence in the criminal justice system is essential for the proper functioning of the system and for the stability and cohesion of the broader society. Public confidence in the criminal justice system encourages compliance with the law, a more engaged community who will report crimes, assist with investigations and collaborate on crime prevention initiatives, and more effective policing as positive relationships will help with the gathering of information and ways to respond more effectively. Public confidence also prevents vigilantism or social unrest and is closely related to the legitimacy of the government, as a loss of trust in the legal system can erode overall confidence in the government’s ability to maintain law and order.

This makes crime and how the criminal justice system responds an important issue that is closely monitored by government opposition parties, with problems and instances of injustice receiving significant political scrutiny. These stories also make good news headlines because they typically involve drama and emotion, focus on safety and are of public interest, and have characteristics that are considered ‘newsworthy’ (e.g., proximate, prominent, timely and involving conflict).

A recent example of youth crime in Queensland demonstrates the complex interplay between public confidence, the media and politics – with evidence suggesting that there is a small group of highly persistent youth offenders who are accounting for increasing proportions of crimes, while there are reductions in one-off offenders. These young people were reported as being from highly specific locations where youth crime was reported by the media as being out-of-control.

Pressure for change brought by victim right groups and facilitated by the media and political processes brough about change including a police-led taskforce, increased police patrols, increased penalties for specific offences and encouraging use of supervision and stricter sentences by the judiciary for repeat offenders, greater funding for victims and the establishment of the Independent Ministerial Advisory Council (IMAC) that will provide advice to government aimed to promote and support victims and their rights.

Whether this group will be able to reduce victimisation in the community remains to be seen, which will necessarily involve addressing the drivers or root causes of crime if changes are to have a positive and lasting impact.

Watch Diana discuss this research and her findings. Video Transcript [Microsoft Word].

The media can also contribute to how people understand crime in other ways. One frequent concern is the role of social media and the internet in contributing to criminal beliefs and behaviours, especially online extremism.

Right-wing extremism (‘RWE’) is a growing threat around the world. It has provided the underlying ideology for terrorist attacks, most prominently in Christchurch, New Zealand, El Paso, Texas, and Halle, Germany. While the Christchurch attacks were not committed in Australia, the shooter was an Australian, which indicated a more localised threat. In addition to this violent threat, RWE poses a wider threat to society because of the division and hatred it generates. Both ‘old’ and ‘new’ styles of RWE – those deriving from a longer tradition of neo-Nazi groups, as well as those with anti-Muslim or pro-nationalist sentiments – aim to cultivate hatred, particularly towards minority groups. Countering far-right ideology creates significant challenges. One is the ideological overlap with beliefs held by ultra-conservative political parties as well as the easy spread of hatred, conspiracy, and false information in the online space. The threat of RWE is therefore significant in Australia, as well as transnationally, and continues to expand.

A broader qualitative analysis approach (small-n) focused on online articles as text data was adopted to enable deeper evaluation of the subtleties of what can be found in the information of the data collected, and provide insight into human experiences as well as observations. This enabled me to identify patterns and themes. In conjunction with my supervisor Dr. Keiran Hardy, we identified five far-right websites that disseminated news-like content: Freedom and Heritage, the Richardson Post, New Australian Bulletin, Australia First Party and XYZ. I then explored the rising concern of RWEDS conveyed in a selection of articles to identify the ideological markers of RWE in Australia, focusing in particular on whether this ideology could be accurately described as ‘nativist’. I selected a feasible timeframe covering articles released between 2018 to 2021. I first identified the total number of articles released in these last four years – by running a filter search and manual count. Longer articles were chosen to allow for easier identification of themes and greater capacity to identify ideological markers of RWE. I selected eight articles per website (giving 40 in total). After producing this database of articles, I analysed the article text according to core concepts discussed in the literature review, including nativism, nationalism, and fascism. From here, I identified, coded, and analysed relevant topics across the selection of online articles.

My study identified a total of 8 coded topics across the article sample (n=40) being nativism, anti-Muslim and Islamic attacking westerners, anti-jews, COVID-19, anti-China, anti-foreigners, racism, speech suppression, and free speech. In the selection of articles studied, 26% of articles expressed anti-foreigner sentiment, followed by racism (15%) with nativist beliefs tying in at 12% with anti-China sentiment.

Despite these findings, nativist beliefs are increasingly manifesting within Australian RWE ideology. As my research has indicated, 12% of articles from the dataset expressed nativist beliefs, for example:

“Being born in Australia does not make you Australian. Only blood makes you Australian. Australians are descendants of the Anglo/Celtic/Saxon people who settled this land prior to 1945. Since then we have imported millions of foreign invaders, who have bred millions of foreign invaders.”

My study is the first to provide clarity and insight into nativism’s influence in the dissemination of RWE ideology in Australia. Nativism provides a particularly interesting lens to understand RWE in an Australian context given Australia’s history as a settler colony and the historical experience of First Nations peoples. This may provide an opportunity to effectively counter RWE, given the historical inaccuracies on which nativist beliefs rely.

There were some limitations to my study. This included, firstly, there being a lack of likes, reads, and comments for the New Australian Bulletin, Australia First Party, and XYZ websites. This prevented insights into the full public reach and impact of each website. In particular, it could not be fully known how many times the articles were spread online and what beliefs the users gained from viewing them, or which they disagreed with. I recognised that it was also difficult to know just from an article what users intended to do with the information (i.e., share, re-post etc.). Even so, this study made an important contribution by having systematically analysed far-right news websites and their content, within an Australian context.

While the label ‘right-wing extremism’ was rejected by ASIO in early 2021 and replaced with the ‘ideologically motivated violent extremism’ label, this does not eliminate RWE’s alliance with ultra-conservative political views, and the fact that it significantly differs from the Islamist threat not only growing Australia wide but globally. Moving forward, the research undertaken via my thesis may be utilised as a basis for further, larger-scale empirical study of far-right news websites and the rise of nativist beliefs.

System Coordination and National Frameworks

On one hand, the ‘criminal justice systems’ in Australia may be viewed as being fragmented and disjointed – both internally, when considering the connections between police, courts and corrections in one jurisdiction – and externally, when considering jurisdictional differences and fragmentation. There is considerable variation in the main components which are largely shaped by and responsive to local issues and problems.

On the other hand, there is frequently coordination between criminal justice agencies who participate in cross-government committees focused explicitly on improving coordination and/or with a more specific focus such as reducing biases and the risk factors for different kinds of offending, such domestic and family violence or youth offending. This coordination occurs at all levels across departments – from the Director and Director-General levels and senior policy levels through to the local level where senior leaders work across departments such as through the use of dual responders involving police and youth justice officers to respond to youth offending, or with the local community to address wider issues and problems.

At a national level, there are attempts at a coordinated response to address identified issues or problems, such as Indigenous over-representation in the criminal justice system, or to promote better cross-jurisdictional laws such as for counter-terrorism legislation or fraud and financial crime. For example, there is a national agreement through the Council of Australian Governments (COAG) to close the gap on 19 national socio-economic targets for Indigenous Peoples which include:

- Reducing Indigenous over-representation in the criminal justice system by at least 15% by 2031.

- Reducing the rate of Indigenous young people (10-17) in prison by at least 30% by 2031.

While changes to the ‘criminal justice system’ to reduce biases and the impacts of laws may reduce overrepresentation, it is generally recognised that the root causes or drivers of crime must be addressed. In this context, the closing the gap agreement aims to reduce several risk factors for offending including children being born heathy and strong, having high quality early education, engaged in education and employment, with safe families and reduced contact with child protection. Our progress against identified goals in these areas is tracked by the Productivity Commission to enable progress to be tracked over time, and responses altered to better achieve desired outcomes.

Youth Justice and the Minimum Age of Criminal Responsibility

In many Australian jurisdictions, the minimum age of criminal responsibility (MACR) is set at 10 years old, meaning that children below this age cannot be found guilty of an offence. The MACR varies globally, ranging from 7 years in certain U.S. jurisdictions to 16 years in Scandinavian countries (Crofts, 2022). However, there are discussions about raising the MACR to 12 or 14 years old, to align with international practices. For instance, Scotland recently increased its MACR from 8 to 12 years (Hidderley et al., 2023). The rationale behind having an older MACR is the belief that children below a certain age lack the understanding of right and wrong and, therefore, should not be held legally accountable for their actions (Hidderley et al., 2023).

Youth are viewed as being distinct from adults as they are developmentally immature, vulnerable, or unstable (Cauffman & Steinberg, 2000; Singh, 2023). Research indicates that at younger ages, children and adolescents exhibit heightened tendencies for seeking rewards and taking risks. Additionally, the pre-frontal cortex, responsible for executive function and decision-making, develops slowly during this period, affecting their ability to regulate impulsive behaviours and comprehend the long-term consequences of their actions (Bateman, 2013; Brown & Charles, 2021; Delmage, 2013; Walsh et al., 2021; Wishart, 2018).

Given this, special processes and practices have developed in what is termed the ‘youth justice system.’ Like the adult systems, each jurisdiction in Australia has a youth justice system, which often includes the main components of the larger adult system, with specialised processes and practices developed to respond more appropriately and effectively to offending by young people. This involves the extensive use of diversion (cautioning and conferencing) for first time and less serious offenders before formal youth court proceedings are used (see Little, Allard, Chrzanowski & Stewart, 2011). An agency focused on youth justice, rather than corrective services, exists to administer the sentences of the youth court and parole board that supervises youth on community-based orders like probation and parole.

Attrition

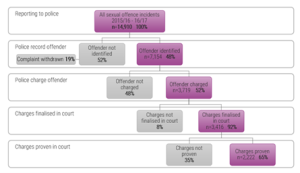

Attrition has been identified as a significant issue, as there is a large gap between the number of crimes committed and the number of offenders who are brought to justice (Prenzler & Sarre, 2020). Mukherjee et al. (1987) found that 4.3% of crimes on average resulted in a conviction and 0.1% resulted in a custodial sentence. More recent research has focused on specific crime types, for example sexual offences, with findings indicating that 15% of sexual offences reported to police result in proven charges (Figure 15.2; Bright, Roach, Barnaba, Walker & Millsteed, 2021).

Source: Attrition of sexual offence incidents through the Victorian criminal justice system: 2021 update by Crime Statistics Agency is licensed under CC-BY 4.0 (Crime Statistics Agency, 2024)

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, the criminal justice system provides some level of safety and reassurance for society and brings some offenders to justice, thereby offering options to support victims and acknowledge their suffering. However, this large, expensive and unwieldy system does not truly address crime, given that much crime is not reported. Where crime is reported, attrition occurs and (relatively) few offenders end up being found guilty of their offences. Even fewer receive sentences. Whatever the sentence, the system is adversarial in nature and the concepts on which the system is based such as ‘fairness’ and ‘justice’ may have different meanings for the parties involved (victim, offender, justice system personnel and community). This invariably means that decisions will be vigorously and hotly debated. The overall effectiveness of the system when judged on the basis of the high recidivism rate or high cost of the criminal justice system per person in the population highlights the need for prevention, and addressing the root causes of crime. At the same time, the criminal justice system needs to be made as fair, effective and efficient as possible – which necessarily involves the removal of party politics from the process and address the needs of over-represented groups such as Indigenous Australians (Prenzler & Saare, 2020).

Check Your Knowledge

Discussion Questions

- Which goal or goals of the system and its components do you think is or are the most important. Why.

- What goals of the overall criminal justice system and its components are inconsistent with each other, or may come into conflict.

- It is proposed that the criminal justice system upholds to principle of justice as laws are applied to everyone and the administration of justice is applied impartially. Do you agree or disagree with this proposition, and why

References

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. (2023a). Welfare expenditure.

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. (2023b). Health expenditure.

Australia Strategic Policy Institute. (2021). The cost of defence ASPI defence budget brief 2021-2022. Canberra: ASPI.

Allard, T., McCarthy, M., & Stewart, A. (2020). Costing Indigenous and non-Indigenous offender trajectories: Establishing better estimates to assist the evidence-base and prevent offending. Canberra: Australian Institute of Criminology.

Anderson, P., & Newman, D. (1993). Introduction to criminal justice (5th ed.). United States of America: R. R. Donnelley & Sons Company.

Ashworth, A. (1994). The criminal process. United States of America: Oxford University Press Inc.

Bateman, T. (2013, 2013/06/01). Keeping up (tough) appearances: the age of criminal responsibility. Criminal Justice Matters, 92(1), 28-29. https://doi.org/10.1080/09627251.2013.805372

Brisbane Times, 2011. https://www.brisbanetimes.com.au/national/queensland/queensland-police-spend-40-per-cent-of-their-time-on-domestic-violence-calls-20210806-p58ge5.html

Brown, A., & Charles, A. (2021). The minimum age of criminal responsibility: The need for a holistic approach. Youth Justice, 21(2), 153-171. https://doi.org/10.1177/1473225419893782

Bryett, K., Casswell, E., Harrison, A., & Shaw, J. (1993). Criminal justice in Australia. Australia: Butterworths.

Cauffman, E., & Steinberg, L. (2000). (Im)maturity of judgment in adolescene: Why adolescents may be less culpable than adults. Behavioral Sciences and the Law, 18, 741-760. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/store/10.1002/bsl.416/asset/416_ftp.pdf?v=1&t=j00hh542&s=77efa6f6f42b4bb02adfe1a49bcac522cafa4d0b

Crofts, T. (2022). Act now: raise the minimum age of criminal responsibility. Current Issues in Criminal Justice, 35(1), 118-138. https://doi.org/10.1080/10345329.2022.2139892

Delmage, E. (2013). The minimum age of criminal responsibility: A medico-legal perspective. Youth Justice, 13(2), 102-110. https://doi.org/10.1177/1473225413492053

Hawkins, G., Biles, D., & Wilson, P. (1970). Criminal justice system. Australia: Paul Wilson.

Hidderley, L., Jeffs, S., & O’Leary, J. (2023). Sentencing of offences committed by children aged under 14 in Queensland Research brief No 2. Queensland Sentencing Advisory Council.

Little, S., Allard, T., Chrzanowski, A., & Stewart, A., (2011). The use and impact of police diversionary practices and alternatives for reducing Indigenous over-representation. Brisbane: Griffith University.

Prenzler, T., & Sarre, R. (2020). The criminal justice system. In H. Hayes and T. Prenzler (Eds.). An Introduction to crime and criminology (5th ed.). Melbourne: Pearson.

Productivity Commission. (2023). Report on Government Services 2021-2022. Canberra: Productivity Commission.

Sallman, P., & Willis, J. (1984). Criminal justice in Australia. Melbourne: Oxford University Press.

Singh, Y. (2023). Old enough to offend but not to buy a hamster: The argument for raising the minimum age of criminal responsibility. Psychiatry, Psychololgy and Law, 30(1), 51-67. https://doi.org/10.1080/13218719.2022.2134229

Travis, L. (1990). Introduction to criminal justice. United States of America: Anderson Publishing Co.

Walsh, T., Fitzgerald, R., Scarpato, C., & Cornwell, L. (2021). Raise the age – and then what?: Exploring the alternatives of criminalising children under 14 years of age. James Cook University Law Review, 27, 37-56. https://search.informit.org/doi/10.3316/agispt.20220201061365

Wishart, H. (2018). Young minds, old legal problems: Can neuroscience fill the void? Young offenders & the age of criminal responsibility bill—promise and perils. The Journal of Criminal Law, 82(4), 311-320. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022018318779830

- FELEG refers to the law enforcement arm of the Five Eyes intelligence alliance that exists between Australia, New Zealand, the United Kingdom, the United States and Canada. ↵

- FELEG refers to the law enforcement arm of the Five Eyes intelligence alliance that exists between Australia, New Zealand, the United Kingdom, the United States and Canada. ↵