7 The Where, When and How of Crime: Principles of Environmental Criminology

Michael Townsley

Learning Objectives

- Familiarise students with the concept of environmental criminology, differentiating it from traditional criminological approaches and highlighting its significance in understanding crime patterns.

- Learn about the interplay between physical and social environments and their influence on criminal opportunities, examining how location design, layout, and societal dynamics either foster or reduce opportunities for crime.

- Explore real-world applications of environmental criminology, addressing its criticisms and contemplating potential future directions in the field.

Before You Begin

- Have you ever acted differently in a situation because of where you were or who you were with? Can you think of examples where your behaviour changes because of the environment that you are in? Do you act the same way in a house of worship as you do in a shopping centre?

- Can you think of why certain times of day would be more conducive to criminal activities than others? Can you think of real-world examples where time plays a significant role in the occurrence of crimes?

- Reflect on a location you’re familiar with (e.g., your campus, a local park, or shopping centre). How do its design and layout potentially influence opportunities for criminal activity? What changes could be made to reduce these opportunities?

INTRODUCTION

The heist film has long been a popular genre, captivating audiences with the portrayal of criminals orchestrating grand and often convoluted schemes. Invariably, there is a pivotal scene where the characters gather together to plan their criminal operation. The mastermind, armed with insider information, brandishes blueprints of the targeted bank or an encyclopaedic understanding of security protocols and patrols. These plot points often allude to the clandestine ways they acquire this intelligence—lines like “I have a friend down at the planning office…” are commonplace. Moreover, these films meticulously depict a detailed plan, carefully describing each member’s role, from the getaway driver to the safe cracker. These scenes serve a purpose beyond mere entertainment; they establish the criminals as methodical, organised, and seasoned in their craft.

Have you ever found yourself wondering how these fictional criminals manage to acquire such crucial intelligence and orchestrate their schemes? This chapter delves into the realm of environmental criminology, providing answers to these intriguing questions. By the end of this chapter, you will gain insight into the resource constraints that offenders face, the necessity of targeting familiar environments and the ever-present pressure of time constraints. Successfully executing a crime requires considerable investment of time and effort, as we shall explore.

Traditional criminology and many criminal justice policies place an emphasis on understanding the motivations and characteristics of offenders, for the purposes of rehabilitation or deterrence (see Chapter 4 for more information about deterrence). Environmental criminology takes a different stance. It acknowledges the pivotal role that opportunity plays, often stemming from the physical and social environment, in shaping the occurrence of criminal acts. Understanding criminal opportunity emerges as a crucial lever for preventing crime (Bruinsma & Johnson, 2018; Clarke, 2012; Wortley & Townsley, 2017).

Environmental criminology examines the intricate interplay between the physical and social environment and criminal behaviour. It dissects how a location’s design, layout, and social dynamics can either foster or diminish opportunities for criminal activity. Furthermore, it probes into how time influences the availability of criminal opportunities, resulting in variations in crime patterns over time, with certain periods proving more conducive to criminal activities than others (Ratcliffe, 2006; Tompson & Coupe, 2018).

This chapter aims to provide you with an overview of environmental criminology and its significance in the realm of crime studies. We will delve into the foundational principles of this discipline, centering on the relationship between location, time, and criminal activity. We will navigate through the major theories underpinning environmental criminology and explore its real-world applications. To conclude, we will address major criticisms and contemplate future directions in this field.

HISTORICAL CONTEXT

A number of forces led to the development of the environmental criminology. The 19th and 20th centuries saw large population increases to cities, particularly in North America. This change in urban living patterns resulted in changes to lifestyles, such as the amount of leisure time and household wealth, and the level and types of crimes committed. This section briefly explains the role that these factors played in creating the theoretical framework that led to environmental criminology.

Early criminological schools of thought, such as the Chicago School (see Chapter 6), played a significant role in shaping the foundation of environmental criminology. The Chicago School, led by scholars like Clifford Shaw and Henry McKay, focused on the social ecology of crime and the spatial distribution of criminal behaviour. Their research in the early 20th century revealed that crime was concentrated in certain neighbourhoods with high population turnover, which they attributed to social disorganisation (Baldwin, 1979; Bottoms, 2018; Shaw & McKay, 1969).

As agriculture became increasingly mechanised and automated, large groups of people moved from the country to cities looking for work. In addition, an influx of migrants from two world wars greatly elevated residential populations in the major cities of Western countries. As cities grew rapidly during the 20th century, crime rates also increased. This phenomenon led researchers to explore the relationship between urbanisation and crime. Scholars like C. Ray Jeffery called for a new school of thought within criminology to better understand the environment in which crime occurs (Andresen, 2018). This shift in focus from individual characteristics to the role of the environment laid the groundwork for environmental criminology (Jeffery, 1969).

Sociology and geography have played crucial roles in shaping environmental criminology. Sociological theories, such as social disorganisation theory, emphasised the impact of social factors on crime patterns. These theories highlighted the importance of neighbourhood characteristics, such as poverty, unemployment, and residential instability, in shaping criminal behaviour (Bottoms, 2018). Geography, on the other hand, provided the spatial framework for understanding crime patterns. Geographic information systems (GIS) and spatial analysis have been instrumental in mapping crime and identifying spatial distributions of crime (Andresen, 2018; Boggs, 1965; Schmid, 1960a, 1960b).

THEORY DESCRIPTION

Environmental criminology is grounded in three core theories: Rational Choice Theory, Routine Activity Theory, and Crime Pattern Theory.

Rational Choice Theory

Rational Choice Theory, first proposed by Derek Cornish and Ron Clarke[1] (Clarke & Cornish, 1985; Cornish & Clarke, 1986a, 2017), is a criminological perspective that views criminal behaviour as the result of rational decision-making processes. According to this theory, individuals weigh the potential benefits and costs of engaging in criminal activities and make choices based on their perceptions of the rewards and risks involved. For example, consider someone contemplating robbing a convenience store. The benefits might include cash and relief from financial strain but this needs to be weighed against the possible consequences like legal repercussions, reputational damage, and potential confrontations. Knowledge that the store lacks surveillance will increase the attractiveness of the opportunity, but its proximity to a police station could act as a deterrent.

Rational Choice Theory emphasises that offenders’ choices are not solely driven by internal motivations or predispositions but are also shaped by external factors such as situational opportunities and constraints. It recognises that offenders’ desires, preferences, and motives are similar to those of non-criminals, and that criminal behaviour is a result of the interaction between these individual factors and the immediate circumstances (Cornish & Clarke, 2017).

This perspective highlights the importance of understanding the decision-making processes of offenders and the situational factors that influence their choices. It suggests that crime prevention efforts should focus on altering the opportunities and constraints that offenders face, rather than solely targeting their motivations or characteristics. By manipulating the environment and making criminal behaviour less attractive or more difficult, it is believed that crime can be deterred or prevented (Clarke, 1995).

Overall, Rational Choice Theory provides a framework for understanding how individuals make decisions about engaging in criminal activities and emphasises the role of situational factors in shaping these choices. It offers insights into the rationality of offenders’ decision-making processes and informs strategies for crime prevention and control (Cornish & Clarke, 1986b).

Routine Activity Theory

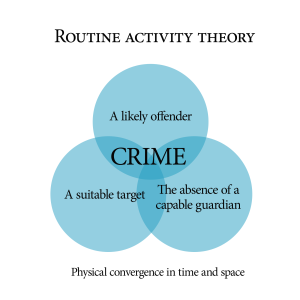

Routine Activity Theory (RAT), proposed by Cohen and Felson (1979), postulates that for a crime to occur, three elements must converge in time and space: a motivated offender, a suitable target, and the absence of capable guardians. (see Figure 1). To illustrate, imagine a university student who has a habit of studying late at the library. One evening, they decide to study at a quiet park and in doing so leave their laptop momentarily unattended to get a drink from a nearby store (NB[2]: this is not a criminology student!).

This park, unknown to the student, is occasionally frequented by opportunistic thieves. Here, the elements of Routine Activity Theory converge: the laptop becomes a suitable target, the opportunistic thief is the motivated offender, and the absence of the student or any vigilant bystanders represents the lack of a capable guardian. Consequently, the chances of a crime (theft) occurring are heightened. This theory underscores the significance of routine activities in influencing crime rates, emphasising that altering any one of these elements can prevent a potential crime (Bruinsma & Johnson, 2018; Felson, 2008; Sampson et al., 2009).

To unpack the theory a little; motivated offenders refer to individuals who have the inclination or desire to engage in criminal behaviour. Suitable targets are objects or individuals that are attractive to offenders due to their perceived value or vulnerability. Capable guardians, on the other hand, are individuals or factors that can effectively prevent or deter crime, such as the presence of law enforcement, security measures, or vigilant community members (Bruinsma & Johnson, 2018; Felson & Clarke, 1998).

RAT emphasises the importance of routine activities in shaping crime patterns. Routine activities refer to the regular patterns of behaviour that individuals engage in as part of their daily lives, such as going to work, school, or socialising. These routines create opportunities for crime when motivated offenders and suitable targets come together in the absence of capable guardians (Bruinsma & Johnson, 2018; Summers & Guerette, 2018).

RAT suggests that changes in routine activities and the spatial and temporal (time) context of criminal events can influence crime rates. For example, an increase in the number of unguarded homes during the day due to changes in work patterns or an increase in the number of potential targets in a specific area can lead to an increase in crime (Bruinsma & Johnson, 2018; Felson & Clarke, 1998).

In summary, RAT provides a framework for understanding how the convergence of routine activities, motivated offenders, suitable targets, and the absence of capable guardians can contribute to the occurrence of crime. By identifying and addressing these elements, RAT offers insights into crime prevention strategies and the design of environments that can reduce criminal opportunities.

Routine Activity Theory by P. S. Burton is licensed under CC-BY-SA 3.0

Crime Pattern Theory

Crime Pattern Theory, developed by Brantingham and Brantingham (1993), says that crimes are not randomly distributed but rather form patterns because of the daily activities and routines of potential offenders. Offenders become familiar with certain areas because of their daily routines, and if opportunities for crime exist within these “activity spaces”, they are more likely to take advantage. Offenders are more likely to commit crimes in areas they know and frequent, as familiarity reduces their risk of apprehension. This theory builds on the rational choice perspective and the routine activity approach, which consider the decision-making processes of offenders and the routine activities of potential victims (Brantingham & Brantingham, 2008).

To illustrate this theory, let us speculate on the process a professional burglar goes through to locate a suitable house to break into. Imagine a typical suburban neighbourhood containing residential streets, parks or playgrounds, a school and a commercial strip of shops. The shops attract both locals and outsiders passing through. Every morning our burglar buys a coffee at the café and scans the neighbourhood.

Over time, specific patterns capture the burglar’s attention. Every morning at 7 am, Mr. Smith, an elderly resident, leaves his house to walk his dog and spends nearly an hour at the café before returning home. On another street, every day, a couple dashes out of their corner house, absorbed in their morning run, leaving behind an empty residence. The daily school bus routine also presents a pattern. Numerous parents leave their homes with their children in tow, heading for the bus stop, and they don’t return until they’ve seen their kids off. Additionally, the burglar notices a trend on Tuesdays: garbage day. By 7 am, most houses position their bins outside. However, a few bins appear later in the morning, hinting at residents who might still be indoors.

After careful observation, our burglar assesses his options. The couple’s house, despite its predictable emptiness, seems a risky venture. Their driveway flaunts newer model cars, suggesting the potential presence of a state-of-the-art home security system. The homes that adjust their garbage routine also raise alarms for him; they indicate unpredictable movements, suggesting someone might be home during unusual hours. This scrutiny leads to Mr. Smith’s residence. The elderly man’s routine is as consistent as clockwork, and there are no signs of security measures outside the house. To him, it stands out as the most vulnerable and attractive target.

Offenders, through observation of routine activities i.e., Routine Activity Theory), discern patterns and vulnerabilities in everyday life. They leverage this information to recognise potential criminal opportunities, choosing targets based on perceived ease and minimal risk (i.e., Rational Choice Theory).

These three core theories of environmental criminology provide complementary perspectives on the causes and patterns of crime. Rational Choice Theory focuses on individual decision-making, Routine Activity Theory examines the broader context of everyday activities, and Crime Pattern Theory explores the spatial distribution of crime. By integrating these theories, researchers and practitioners can gain a more comprehensive understanding of crime and develop effective strategies for crime prevention.

Australian Residential Burglary: Self-Protective Behaviour and Security Opportunities

An Honours Thesis completed by Katrina Nilsson

It might surprise you, but burglary is one of the most impactful victimisation experiences that affects up to a quarter of a million Australians per year. This is because of the negative impacts associated with residential burglary, such as physical harm, monetary loss, psychological harm, and the chance of being burgled again. However, even with the knowledge of these harms, only roughly 30% of victims make any changes to their level of security from before they were burgled. Finding out how and why people take or do not take measures to protect themselves against burglary is the first step to reducing the opportunities for burglary to occur.

Data for this project was collected online through a survey tool called Lime Survey for three months. Using social media to advertise the research, 113 participants’ answers were used to compile the results. The survey measured seven themes. The dependent variable measured residential security presence using self-reports on the presence of selected security measures on Australian residences. This way, we could see what each participant already had on their home, which also answered research question one. The survey also asked about demographics such as age, gender, and tenancy type. Using Likert scales, it measured levels of security knowledge, self-protective behaviours, prior victimisation, perceptions of crime, routine activities, and guardianship attitudes. We also asked open-ended questions regarding whether the participant was responsible for implementing the security/device and reasons for or against the implementation of security/devices were also asked.

Overall, we found that the most common form of security was the presence of deadlocks on doors, followed closely by security screens on windows. Our most surprising result was that renters were less likely to have security on their homes, and 7% of participants stated that even though they wanted to improve their security, they were incapable of doing so because they rented. We found that those with higher guardianship attitudes were more likely to instal security measures that aided in line of sight, specifically sensor lighting. Interestingly, we also found that many people who had installed locks for fences or gates since moving to their property were the owners of dogs and that dog owners were more likely to have alarms in their homes.

These results show that even when not physically available, guardianship attitudes still play an essential part in overall crime prevention, adding to the knowledge of the application of passive guardianship. The study’s results also showed that there are still barriers to reducing crime opportunities for participants, even when willing to do so. Recommendations were made to combat these barriers, including increasing the minimum level of security of newly built residences to include deadlocks on doors and locks on windows. It was also recommended that the government incentivise increasing security on property to increase Australian security levels on a broad spectrum. These recommendations would promote the importance of community safety and reduce the opportunities of burglary.

We often expect that people will improve their security if they know how to and the importance of it, but our research clearly shows that just because you want to does not mean you always can. We should spend more time researching and understanding the barriers to preventing crime and not just the opportunities to commit the crime.

THEORY APPLICATION

Having briefly described the theoretical framework of environmental criminology, let us look at how this can be applied to the prevention of crime. If we understand the role that opportunity plays in crime events, then preventing crime is about altering the supply of opportunities. In this section we will discuss three different applications of environmental criminology: situational crime prevention, crime prevention through environmental design (CPTED), and design against crime.

Situational Crime Prevention

Situational crime prevention is a practical and effective approach to reducing specific crime problems by altering the situational determinants of crime to make it less likely to occur (Clarke, 1995; Clarke, 1997). It involves implementing measures that increase the effort required to commit a crime, increase the risks of detection and punishment, reduce the rewards of crime, and remove excuses or provocations for criminal behaviour (Clarke, 2017). These measures can include target hardening (e.g., installing security cameras or locks), increasing surveillance (e.g., through the presence of security personnel), and altering the physical environment to reduce opportunities for crime (Clarke, 1983).

The effectiveness of situational crime prevention has been demonstrated through numerous case studies and evaluations (Center for Problem-Oriented Policing, 2011; Welsh & Taheri, 2018). It has been found to have a significant impact on reducing crime, and there is little evidence to suggest that it simply displaces crime to other areas or forms (Guerette & Bowers, 2009). By focusing on the immediate situational causes of crime, situational crime prevention can achieve more immediate and tangible results in crime reduction compared to approaches that target dispositional causes (Felson & Clarke, 1998).

Crime Prevention Through Environmental Design

Crime Prevention Through Environmental Design (CPTED) is a theory and practice that aims to reduce crime and enhance safety by manipulating the physical environment in which crime occurs. It is based on the understanding that the design and organisation of spaces can influence human behaviour and the occurrence of criminal activities (Armitage, 2017; Jeffery, 1977).

CPTED focuses on four key principles: natural surveillance, territoriality, access control, and maintenance. Natural surveillance involves designing spaces in a way that maximises visibility and allows for easy monitoring by residents, employees, or passersby. Territoriality refers to creating a sense of ownership and responsibility among individuals for specific areas, which can deter potential offenders. Access control involves regulating the movement of people using physical barriers, such as fences or gates, to prevent unauthorised entry. Maintenance emphasises the importance of keeping the environment clean, well-lit, and well-maintained, as neglect can signal a lack of guardianship and attract criminal activity (Taylor, 2018).

By implementing CPTED principles, the physical environment can be modified to reduce opportunities for crime and increase the perception of safety. This can be achieved through various strategies, such as improving lighting, removing hiding spots, enhancing natural surveillance, and promoting community involvement in the design and maintenance of public spaces (Armitage, 2017).

The Night-Time Economy (NTE) is a substantial contributor to local and national economies, but may be curtailed by perceptions of lack of safety from violence. NTE venues are characterised by a range of social harms. Some NTE venues contribute more than others to associated crime, indicating that characteristics of the venue play a significant role in the occurrence of violence and crime, and campaigns and policies targeting patron behaviour can only achieve so much. Improving lighting is a common situational crime prevention technique which has been utilised outside of licensed premises but had not been specifically examined as a potential factor inside licensed premises, meaning that while good levels of lighting are recommended to venues, it is unclear what those levels should be.

We completed two studies in order to answer our research questions. The first study used a purposive sample of high risk and comparison licensed premises in Queensland (N=60), while the second used a random sample of premises in Queensland (N=90). All premises were primarily a commercial hotel or nightclub. Previous studies had involved researchers making a judgment about the level of lighting inside venues, but we took that a step further and instead used a lux meter to measure the median lighting level across areas in each venue objectively. We collected information on other possible drivers of crime and violence identified in our review of the literature, like venue cleanliness and food service, venue size and numbers of security. We then created a count of the violent crime incidents that happened in the hours of darkness which were associated with the premises during the year prior to data collection for each venue. In each study, we controlled for the maximum number of patrons ever at the venue, and in the second study, we also controlled for whether the venue operated within a Safe Night Precinct (SNP).

Our most interesting findings were that when the median lux in a premises was less than 10 lux, there was almost a 100% chance that violence would occur on that premises. When the median lux level was greater than 20, there was almost no chance of a violent incident. When we used a model to examine the number of violent incidents (rather than whether or not one occurred), we predicted that zero violent incidents was possible at 16 lux, but again likely above 20, and for every fall in 10 lux below that threshold of 20 lux, there would be an extra two violent incidents recorded at that premises. Venues within the SNP areas in Queensland had greater levels of violence than those outside, but the median lux level at which the number of violent incidents would probably reduce to zero is the same as non-SNP venues.

The results objectively confirm the relationship between lighting and violence in licensed venues, and suggest a minimum lux level associated with the minimisation of violence that could be established via regulation. In addition, increasing lighting levels across licensed venues would be likely to be associated with greater reductions in violence in SNP areas than non-SNP areas. It is important to remember that lighting is likely one of a constellation of environmental and situational factors that render some licensed premises more susceptible to violence than others, and that our results don’t indicate that poor lighting causes violence, just that there is an association. Further research is needed to identify the cluster of licensed premises characteristics that produce violent environments with a goal of further reducing the likelihood of harm.

A lot of emphasis is put on individual behaviour and responsibility for violence in the night-time economy in our society, but our research clearly shows a relationship between lighting in a venue and the amount of violence that occurs in and around it. The takeaway is that characteristics of the environment attract certain types of people and allow for or even encourage certain types of behaviour, supporting a situational crime prevention approach to minimising harm in places of social interaction.

Design Against Crime

Design against crime refers to the intentional design and modification of products, systems, and environments to prevent or reduce the occurrence of criminal activities (Ekblom, 2017). It involves incorporating crime prevention principles into the design process to create products that are less attractive to criminals or that make it more difficult for them to commit crimes. This approach aims to address the criminogenic features of products and environments, such as their attractiveness as targets or their facilitation of criminal behaviour (Davey & Wootton, 2017).

By considering the potential misuse or vulnerability of products and environments, designers can anticipate and address the factors that may contribute to criminal activities. This may involve incorporating features that deter theft or misuse, such as secure locks, tamper-resistant materials, or surveillance measures. Design against crime also emphasises the importance of creating products and environments that promote natural surveillance, making it easier for potential witnesses to observe and intervene in criminal activities (Ekblom, 2013).

The goal of design against crime is to create products and environments that reduce criminal opportunities and increase the risk and effort required for criminal behaviour. As such, design against crime is a multidisciplinary approach that combines principles from criminology, design, and other related fields to create products and environments that are less susceptible to criminal activities. It recognises the role of design in shaping behaviour and aims to proactively address the factors that contribute to crime (Clarke & Newman, 2005).

Overall, while situational crime prevention concentrates on modifying specific situational factors, CPTED takes a broader approach by considering the overall design and layout of an environment. Design against crime focuses on incorporating crime prevention strategies into the design of products, systems, and infrastructure.

Together, these approaches contribute to creating safer and more secure environments by addressing different aspects of crime prevention.

CASE STUDIES

This section outlines two recent studies using opportunity reduction to prevent crime in Australia.

Case Study 1: Illegal Fishing in Australia’s Great Barrier Reef Marine Park

Scenic Flight over Great Barrier Reef by Sebastian Cruz is licensed under CC-BY-NC 2.0

The Great Barrier Reef Marine Park is a globally significant marine protected area facing challenges from illegal fishing activities. By analysing the opportunity structure of illegal, unreported, and unregulated (IUU) fishing, Weekers et al. (2021) identified key micro-spatial risk factors, such as proximity to landing ports and the availability of target fish species. The researchers then used this information to address IUU fishing using opportunity reduction strategies.

By targeting the risk factors that facilitate illegal fishing, these strategies have led to immediate and lasting outcomes. For example, enhancing fishery licensing and offload regulations have been effective in reducing the opportunities for illegal fishing. Additionally, targeting enforcement efforts in hot spot locations has increased the perceived risks of apprehension for would-be offenders. The combination of these strategies has contributed to the prevention and reduction of illegal fishing activities in the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park.

Case Study 2: Opportunity Reduction Strategies to Prevent Sexual Abuse in Schools

Robertson et al. (2023) suggest that opportunity reduction can be applied to prevent sexual abuse in schools. Opportunity reduction aims to increase the effort required to commit a crime in the following ways:

- Targeting High-Risk Locations: Identifying and addressing high-risk locations within educational settings is crucial. They highlight the need to extend prevention efforts beyond the confines of school premises and consider external locations where abuse may occur. By implementing measures such as increased surveillance, controlled access to facilities, and target hardening, the opportunity for sexual abuse can be reduced.

- Enhancing Guardianship: Increasing the presence of capable guardians in educational settings can act as a deterrent to potential offenders. This can be achieved through strategies such as improving supervision and management of staff, clarifying protocols for conduct and reporting, and providing training for staff members.

- Modifying Intimacy-Promoting Situations: Educational contexts often involve situations that can facilitate the development of inappropriate relationships. Robertson et al. (2023) suggest modifying these situations to reduce the opportunity for abuse. Strategies may include implementing rules and guidelines regarding one-on-one interactions between staff and students, discouraging isolated meetings, and promoting a culture of accountability and transparency.

THEORY CRITICISMS

Environmental criminology has made significant contributions to our understanding of crime patterns and prevention strategies (Welsh & Taheri, 2018), but it is not without criticism. This section will provide a summary of the common criticisms of the environmental criminology perspective and opportunity reduction.

One of the most frequently raised limitations associated with situational crime prevention approaches is the concept of displacement (Barr & Pease, 1990; Eck, 1993; Hesseling, 1994). Displacement can occur when potential offenders, in response to the implementation of crime prevention measures in one location or context, change their criminal activities by either selecting different targets, altering their modus operandi (methods), or relocating to areas where opportunities for crime remain unblocked. In essence, it suggests that situational crime prevention measures, while effective in reducing crime in a particular place or manner, may not necessarily lead to an overall reduction in crime rates but rather a redistribution of criminal activities.

For instance, consider the installation of improved locks on a house to deter burglars. While this measure may make the targeted house less vulnerable to break-ins, it could lead burglars to choose neighbouring houses with weaker security measures, essentially shifting the crime problem from one residence to another within the same street or area. This phenomenon is known as geographical displacement (Barr & Pease, 1990), where criminal activities are moved to nearby locations.

Displacement can also manifest as tactical displacement, where offenders modify their criminal techniques or choose different types of crime within the same area. In the context of burglary, for example, burglars may adapt by using more sophisticated methods, targeting different types of property, or focusing on theft rather than breaking and entering.

Moreover, temporal displacement is another concern, where criminals may adjust the timing of their activities to avoid encountering security measures. For instance, if increased police patrols are implemented during certain hours, offenders might simply shift their criminal activities to times when law enforcement presence is reduced.

Critics of situational crime prevention argue that if displacement occurs extensively, the overall impact of these measures on reducing crime rates may be limited. It raises questions about the long-term effectiveness of such approaches and the potential unintended consequences they may create. It is important to note, however, that reviews of displacement effects in crime prevention studies (Guerette & Bowers, 2009; Johnson et al., 2014) strongly suggest that situational crime prevention more likely generate a diffusion of benefits[3] than displacement.

Another common criticism of environmental criminology is its neglect of individual characteristics and motivations of offenders (Farrington, 1999). Traditional criminology theories often guide efforts to reduce recidivism by addressing individual factors like substance abuse, mental health issues, and rehabilitation programs tailored to an offender’s specific needs. Environmental criminology, while valuable for understanding crime hotspots, may not provide the same level of guidance for addressing the individual factors that contribute to an offender’s criminal behaviour.

Critics also argue that the environmental criminology perspective tends to overlook the broader social and economic factors that contribute to crime, such as poverty, inequality, and social disorganisation (Cullen & Kulig, 2018). Structural inequities, such as racial disparities in access to quality education, healthcare, and employment opportunities, can contribute significantly to crime rates but are largely ignored by environmental criminologists. By focusing primarily on the immediate physical and social environment, environmental criminology may be addressing symptoms of the problem rather than the real underlying issues, such as the social inequalities that shape criminal behaviour (White & Cunneen, 2006).

Furthermore, environmental criminology has been criticised for its limited consideration of cultural and historical factors. For instance, neighbourhoods in the United States with a history of redlining and discriminatory lending practices often exhibit higher crime rates. These disparities are deeply rooted in systemic racism and historical inequalities in housing and economic opportunities, which environmental criminology may not fully acknowledge. In addition, cultural perceptions of safety can differ widely. In communities with a history of police discrimination, residents may harbour deep-seated mistrust of the police, influencing crime reporting and cooperation with the police. These perceptions are critical yet may not be adequately addressed within the framework of environmental criminology (Cunneen et al., 1995).

In conclusion, environmental criminology has made significant contributions to our understanding of crime patterns and prevention strategies because it focuses on the fundamental causes of crime events (i.e., opportunities). Conventional criminological approaches have focused on the root causes of criminality (e.g., poverty, inequality, unemployment). This distinction lies at the heart of criticisms of environmental criminology and opportunity reduction approaches.

THE FUTURE OF ENVIRONMENTAL CRIMINOLOGY

Environmental criminology emerged in response to evolving societal changes, reflecting the reality that our surroundings significantly influence criminal behaviour. In today’s world, where technology, climate change, and other transformative forces promise to reshape various facets of our lives, the relevance of environmental criminology stands at a critical juncture. As we witness shifts in our daily routines and lifestyles, it is reasonable to ask: will environmental criminology remain relevant in the face of these ongoing changes? In the following section, we delve into some likely areas that environmental criminology should engage with to sustain its effectiveness and continue offering valuable insights into the complex interplay between the environment and criminal activities.

Tech-enabled crime

A pressing concern demanding heightened attention within the field of environmental criminology is the domain of cybercrime (Milivojevic & Radulski, 2020; Miró Llinares & Johnson, 2018). As technology continues to advance at a breakneck pace, and our society increasingly relies on the digital realm, cybercrime has emerged as a profound concern (Newman & Clarke, 2003). For instance, frauds and scams can be perpetrated at a scale previously unimagined thanks to the internet (Bodker et al., 2022; Netacea, 2022; Van Hardeveld et al., 2016; Wang & Topalli, 2023). These digital transgressions transcend geographical borders, rendering conventional approaches to crime control, like legislation and traditional criminal justice mechanisms, less effective in the face of cybercrime’s borderless nature (Collier et al., 2019).

Environmental criminology, however, holds the potential to play a pivotal role in comprehending and mitigating the impact of cybercrime (Miró Llinares & Johnson, 2018). It accomplishes this by delving into the intricacies of cyberspace, dissecting the criminal opportunities it presents, and articulating the modus operandi employed by cyber offenders. By closely examining the architecture of cyberspace and its interplay with criminal behaviour, environmental criminology stands poised to offer invaluable insights into tackling the evolving challenges posed by cybercrime in our technology-driven world.

Crime Script Analysis of Drug Importation into Australia Facilitated by The Dark Net

A Honours Dissertation by Elena Morgenthaler

Watch Elena discuss this research and her findings. Video Transcript [Microsoft Word].

Dark net drug markets are a continually growing platform for illicit drug trafficking globally. These markets are only accessible through browsers (e.g. TOR) which hide the Internet Protocol (IP) address of the user. Dark net markets have been likened to eBay or Amazon where the market facilitates transactions between vendors and buyers. The anonymity provided by the browsers coupled with payments using cryptocurrencies (e.g. Bitcoin, Monero) contributes to the popularity of these markets. Prior to this study there was little knowledge on the crime commission process of offenders, particularly across international borders and in the Australian context.

To study the crime commission process of offenders, a crime script was developed. Crime scripts provide the steps undertaken by offenders from the preparation to the aftermath of the crime. To develop the crime script in this study, court sentencing transcripts were used. These were found using a range of search terms in the Australian Legal Information Institute (AustLII) database. The search results were examined and eliminated based on duplication, irrelevance and lack of information. A total of 18 court cases were used in the qualitative content analysis. The analysis involved a series of stages to combine and organise the information on the crime commission process from the court cases into one crime script.

The crime script developed in this study consisted of four main steps followed by three script tracks (variations of steps) undertaken by offenders (see publication for the crime script figure). The five main steps were preparation, access, purchasing, receiving and storage. Offenders then adopted one of the three script tracks based on the purpose of importation (selling on the dark net domestically, selling offline and personal use). It was also found that offenders repurchased drugs when products were seized by Australian Border Force and after all the script steps were completed. In some cases, offenders worked with others to complete the crime script steps.

The crime script in this research contributes and deepens our knowledge on how offenders import illicit drugs using the dark net. It also provides a template for the development of crime prevention measures. In this study 19 potential crime prevention points were provided. These were tailored to the steps undertaken by offenders when using the dark net to import drugs into Australia. These demonstrate the possibility of interrupting this type of crime at various points during the crime commission process. However, these prevention suggestions were hypothetical and further research needs to be conducted on the effectiveness of these crime prevention strategies.

The majority of research on dark net markets is on the online aspects of offending but this research demonstrates the importance of also studying the offline aspects. By understanding all aspects of the crime commission process it is possible to develop tailored crime prevention measures.

Urbanisation and smart cities

Within the context of climate change and the pursuit of sustainable communities, urban planners have increasingly emphasised the shift towards higher density living as a crucial component (Durand et al., 2011; Hummel, 2020; Maheshwari et al., 2020). Concurrently, the inexorable process of urbanisation, propelled by advancements in technology, is poised to herald the era of the “smart city.” In simple terms, a smart city is defined by its integration of advanced technologies to enhance urban living, from optimising resource management to improving transportation and public services (Anthopoulos, 2015; Camero & Alba, 2019).

This evolution towards smarter urban landscapes presents both opportunities and challenges for environmental criminology. As cities become more densely populated and intricately interconnected, there arises a compelling need to comprehend how the built environment and technological innovations jointly influence crime patterns. For instance, consider the proliferation of surveillance cameras and data analytics in urban areas. While these technologies may serve as powerful tools for enhancing security and crime prevention, they also raise concerns about privacy and potential misuse (Chen & Chen, 2018; Ismagilova et al., 2020).

Expanding into new crimes and countries

Environmental criminology has the potential to broaden its horizons beyond the traditional purview of street-level opportunistic crimes, particularly within Western democratic contexts. While such crimes have constituted its core focus, the field must now embrace a more expansive vision of what crime is.

One potential avenue for this expansion lies in applying environmental criminological principles to the realm of serious and organised criminal activities (Bullock et al., 2010; Bunt & Schoot, 2003; Felson, 2006). The facilitating environment for organised crime includes physical, social, economic, and even political factors. Social relationships, legal entities, companies, and subcultural or ethnic communities all play a role in enabling and supporting organised crime activities (Kleemans et al., 2012; Kleemans, 2018). These concepts rarely feature in applications of situational crime prevention, which typically only consider the decision making of individual rational actors.

Additionally, the field of environmental criminology could embark on a journey of global exploration, transcending geographical boundaries to delve into crime patterns in non-Western countries. This expansion will require a keen sensitivity to cultural differences that may exert a significant influence on the spatial patterns of criminal activities. For instance, the realm of wildlife crimes, encompassing poaching and smuggling (Pires & Clarke, 2011; Thiault et al., 2020) and fishing (Weekers et al., 2021), has only recently emerged as a focus of situational crime prevention (Lemieux, 2014; Schneider, 2008). Environmental criminology, in this context, can contribute to understanding the dynamics of these transnational illicit activities by assessing the environmental and economic factors that drive or inhibit them (Burton et al., 2020).

Stalking and Cyberstalking in Australia: An examination of comparative harms across crime types

A Master’s Disseration by Nakshathra Suresh

While there is extensive research on prevention and intervention measures of stalking in Australia, the rise of cyber abuse in the past decade indicates a need for further research related to its online counterpart, cyberstalking. Knowledge surrounding cyberstalking and its perpetration remains limited and how to effectively intervene and combat the crime in Australia requires more attention. As offenders can move online to cause harm, we decided to ask whether cyberstalking is merely an extension of offline stalking or whether it differs due to the usage of new platforms and technologies. We were also curious to understand whether there were differences in the perceptions of severity and recommendations of help-seeking behaviours for victims of either crime type.

In total, 189 responses were collected but only 126 responses were used (after cleaning and culling the data). We used a unique combination of methods for this study – a quantitative methodology (through responses to a survey promoted through Griffith University’s channels) that utilised vignettes. Vignettes are usually not used in criminology, but are useful in determining perceptions and gauging subjective responses to hypothetical (but real-life) scenarios.

In total, there was one stalking scenario and two cyberstalking scenarios. We asked individuals to assess the impact of the stalker’s actions on the victim’s mental health and wellbeing at each stage of escalation in the scenario. We also asked them to select from recommendations for protective behaviours (implementing self-help behaviours like carrying a weapon, installing cameras etc.) and/or help-seeking behaviours (seeking help from outside sources like family or platform administrators) to suggest to the victim.

Each scenario also had a set of questions at the end which manipulated a specific variable of the original scenario (i.e. the original scenario had a male stalker but at the end, we asked whether their perception would change if it was a female stalker). We were then able to collect perception data based on the respondent’s individual and subjective emotional response associated with the stalking and cyberstalking scenarios.

Offline stalking was perceived to have greater impact on a victim’s mental health and wellbeing than cyberstalking, however previous victimisation of either crime type did not affect this perception. Further, individuals were likely to recommend the implementation of protective behaviours (like installing a VPN or security cameras) in both crime types.

Recommendations between help-seeking behaviours differed between the crime types – such as reporting to the platform administrators for victims of cyberstalking and reporting to law enforcement for victims of offline stalking. This indicated that individuals perceived a greater threat to physical and mental safety for victims of offline stalking, requiring law enforcement intervention.

The study found that individuals are likely to recommend help-seeking behaviours across both cyberstalking and offline stalking scenarios. The inclusion of reporting the behaviour to administrators of the platform meant that this was a preferred recommendation for cyberstalking victims rather than reporting the behaviour to law enforcement for offline stalking. This is perhaps reflective of the view that cyberstalking remains a difficult and challenging task for law enforcement and victims are often left to remedy for themselves a reduction in their own victimisation or delegate this responsibility to the administrators of the online platform.

Future research should focus on examining the socio-cultural and contextual influences that may affect the perceptions of both stalking and cyberstalking and expanding this research to include perpetrators, law enforcement authorities, legal representatives, and intervention providers in the Australian community.

It is important to note that victim blaming persists in today’s society, and that people perceive offline crime as more harmful than cyber crime. Further, there are no solutions for victims of cybercrime that are able to appropriately meet their needs. They are being failed by the criminal justice system and the various institutions that they encounter and are often left to deal with their own negative experiences without the appropriate support mechanisms.

CONCLUSION

Environmental criminology is a field of study examining the intricate relationship between criminal activities and the physical and social environment. This discipline focuses on the role of opportunity in shaping offender decision making, with prevention strategies centred around altering the physical environment to increase the difficulty associated with committing crimes. As a result, environmental criminology has garnered significant attention and influence in guiding criminal justice policies and crime prevention efforts.

Nevertheless, critics have contended that environmental criminology’s explanations remain incomplete, chiefly because it overlooks many other influential contributing factors, including but not limited to inequality, disadvantage, and culture. It is essential to address this critique by acknowledging that environmental criminology primarily directs its investigative lens towards understanding the dynamics of crime events. In this perspective, the root causes of crime events tend to emerge within the immediate environment. In contrast, various alternative criminological approaches focus on criminality, a more extensive, multifaceted and enduring phenomenon. The focus on criminality tends to (rightfully) consider risk factors that are distal (far) with respect to a crime event. For instance, developmental researchers often explore childhood experiences, including exposure to violence, trauma, or neglect, as root causes that can significantly influence an individual’s propensity to engage in criminal behaviour later in life (Farrington, 1995; Loeber & Farrington, 2000). Additionally, socio-economic disadvantages during upbringing, educational attainment, and access to positive role models are also considered important contributors to criminality.

The juxtaposition of environmental criminology with these complementary perspectives enriches our understanding of the interaction between the environment and criminal behaviour. While environmental criminology sheds light on crime events and their immediate contexts, developmental research broadens our comprehension by examining the deeper roots of criminality, encompassing distal factors that shape individuals’ life trajectories and influence their involvement in criminal activities. Collectively, these perspectives contribute to a more comprehensive framework for addressing and preventing crime in our society.

Check Your Knowledge

Discussion Questions

- What are the most significant strengths and limitations of environmental criminology compared to traditional criminological approaches?

- How might environmental criminology principles vary or need adjustments when applied in different cultural or socio-economic contexts around the world?

- With the rise of digital spaces and technology, how can environmental criminology adapt to address “virtual crimes” or crimes in digital environments?

References

Andresen, M. (2018). GIS and spatial analysis. In G. J. N. Bruinsma & S. D. Johnson (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of environmental criminology (pp. 190–209). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190279707.013.33

Anthopoulos, L. G. (2015). Understanding the smart city domain: A literature review. Transforming City Governments for Successful Smart Cities, 9–21.

Armitage, R. (2017). Crime prevention through environmental design. In R. Wortley & M. Townsley (Eds.), Environmental criminology and crime analysis (2nd ed., pp. 259–285). Routledge.

Baldwin, J. (1979). Ecological and areal studies in Great Britain and the United States. In N. Morris & M. Tonry (Eds.), Crime and Justice: An Annual Review of Research (Vol. 1, pp. 29–66). University of Chicago Press. http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0192-3234(1979)1<29:EAASIG>2.0.CO;2-V

Barr, R., & Pease, K. (1990). Crime placement, displacement, and deflection. In M. Tonry & N. Morris (Eds.), Crime and Justice: An Annual Review of Research (Vol. 12, pp. 277–318). University of Chicago Press.

Bodker, A., Connolly, P., Sing, O., Hutchins, B., Townsley, M., & Drew, J. (2022). Card-not-present fraud: Using crime scripts to inform crime prevention initiatives. Security Journal, DOI: 10.1057/s41284-022-00359-w.

Boggs, S. L. (1965). Urban crime patterns. American Sociological Review, 30(6), 899–908.

Bottoms, A. (2018). The importance of high offender neighborhoods within environmental criminology. In G. J. N. Bruinsma & S. D. Johnson (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of environmental criminology (pp. 119–149). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190279707.013.5

Brantingham, P. J., & Brantingham, P. L. (2008). Crime pattern theory. In R. Wortley & L. Mazerolle (Eds.), Environmental criminology and crime analysis (pp. 78–93). Willan Publishing.

Brantingham, P. L., & Brantingham, P. J. (1993). Environment, routine and situation: Toward a pattern theory of crime. Advances in Criminological Theory, 5, 3–28.

Bruinsma, G. J. N., & Johnson, S. D. (2018). Environmental criminology: Scope, history, and state of the art. In G. J. N. Bruinsma & S. D. Johnson (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of environmental criminology (pp. 1–32). Oxford University Press.

Bullock, K., Clarke, R. V. G., & Tilley, N. (Eds.). (2010). Situational prevention of organised crimes (p. 239). Willan Publishing.

Bunt, H. van de, & Schoot, C. van der. (2003). Prevention of organised crime: A situational approach. Boom JuridischeUitgevers.

Burton, C., Cowan, D., & Moreto, W. (2020). Wildlife crime: A situational crime prevention perspective. In Routledge international handbook of green criminology (pp. 68–78). Routledge.

Camero, A., & Alba, E. (2019). Smart city and information technology: A review. Cities, 93, 84–94.

Center for Problem-Oriented Policing. (2011). Situational Crime Prevention Evaluation Database. http://www.popcenter.org/library/scp/ [Last accessed: 9 May 2011]. http://www.popcenter.org/library/scp/

Chen, N., & Chen, Y. (2018). Smart city surveillance at the network edge in the era of iot: Opportunities and challenges. Smart Cities: Development and Governance Frameworks, 153–176.

Clarke, R. V. G. (1983). Situational crime prevention: Its theoretical basis and practical scope. In Crime and Justice: A Review of Research (Vol. 4, pp. 225–256). University of Chicago Press.

Clarke, R. V. G. (1995). Situational crime prevention. In M. Tonry & D. P. Farrington (Eds.), Crime and Justice: A Review of Research (Vol. 19, pp. 91–150). University of Chicago Press.

Clarke, R. V. G. (1997). Introduction. In R. V. G. Clarke (Ed.), Situational crime prevention: Successful case studies (2nd ed., pp. 2–43). Criminal Justice Press.

Clarke, R. V. G. (2012). Opportunity makes the thief really? And so what? Crime Science, 1(3).

Clarke, R. V. G. (2017). Situational crime prevention. In R. Wortley & M. Townsley (Eds.), Environmental criminology and crime analysis (2nd ed., pp. 286–303). Routledge.

Clarke, R. V. G., & Cornish, D. B. (1985). Modeling offenders’ decisions: A framework for research and policy. In M. Tonry & N. A. Morris (Eds.), Crime and Justice: A Review of Research (Vol. 6, pp. 147–185). University of Chicago Press.

Clarke, R. V. G., & Newman, G. R. (Eds.). (2005). Designing out crime from products and systems (Vol. 18). Lynne Rienner Publishers.

Cohen, L. E., & Felson, M. (1979). Social change and crime rate trends: A routine activity approach. American Sociological Review, 44(4), 588–608.

Collier, B., Thomas, D. R., Clayton, R., & Hutchings, A. (2019). Booting the booters: Evaluating the effects of police interventions in the market for denial-of-service attacks. Proceedings of the Internet Measurement Conference, 50–64.

Cornish, D. B., & Clarke, R. V. G. (1986a). Rational choice approaches to Crime. In D. B. Cornish & R. V. G. Clarke (Eds.), The reasoning criminal: Rational choice perspectives on offending (pp. 1–16). Springer-Verlag.

Cornish, D. B., & Clarke, R. V. G. (1986b). The reasoning criminal: Rational choice perspectives on offending. Springer-Verlag.

Cornish, D. B., & Clarke, R. V. G. (2017). The rational choice perspective. In R. Wortley & M. Townsley (Eds.), Environmental criminology and crime analysis (2nd ed., pp. 29–61). Routledge.

Cullen, F. T., & Kulig, T. C. (2018). Evaluating theories of environmental criminology: Strengths and weaknesses. In G. J. N. Bruinsma & S. D. Johnson (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of environmental criminology (pp. 160–174). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190279707.013.7

Cunneen, C., White, R. D., White, R., & White, R. (1995). Juvenile justice: An Australian perspective. Oxford University Press Melbourne.

Davey, C. L., & Wootton, A. B. (2017). Design against crime: A human-centred approach to designing for safety and security. Taylor & Francis.

Durand, C. P., Andalib, M., Dunton, G. F., Wolch, J., & Pentz, M. A. (2011). A systematic review of built environment factors related to physical activity and obesity risk: Implications for smart growth urban planning. Obesity Reviews, 12(5), e173–e182.

Eck, J. E. (1993). The threat of crime displacement. Criminal Justice Abstracts, 25(3), 527–546.

Ekblom, P. (Ed.). (2013). Design against crime: Crime proofing everyday products (Vol. 27). Lynne Rienner Publishers.

Ekblom, P. (2017). Designing products against crime. In R. Wortley & M. Townsley (Eds.), Environmental criminology and crime analysis (2nd ed., pp. 304–333). Routledge.

Farrington, D. P. (1995). The development of offending and antisocial behaviour from childhood: Key findings from the Cambridge study in delinquent development. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 6(36), 929–964.

Farrington, D. P. (1999). A criminological research agenda for the next millennium. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 43(2), 154–167.

Felson, M. (2006). The ecosystem for organized crime. HEUNI 25th Anniversary Lecture (Paper No. 26): The European Institute for Crime Prevention and Control, United Nations.

Felson, M. (2008). Routine activity approach. In R. Wortley & L. Mazerolle (Eds.), Environmental criminology and crime analysis (pp. 70–77). Willan Publishing.

Felson, M., & Clarke, R. (1998). Opportunity makes the thief: Practical theory for crime prevention (Police Research Series 98). Policing; Reducing Crime Unit, Home Office.

Guerette, R. T., & Bowers, K. J. (2009). Assessing the extent of crime displacement and diffusion of benefits: A review of situational crime prevention evaluations. Criminology, 47(4), 1331–1368.

Hesseling, R. (1994). Displacement: A review of the empirical literature. In R. V. G. Clarke (Ed.), Crime prevention studies (Vol. 3, pp. 197–230). Criminal Justice Press.

Hummel, D. (2020). The effects of population and housing density in urban areas on income in the United States. Local Economy, 35(1), 27–47.

Ismagilova, E., Hughes, L., Rana, N. P., & Dwivedi, Y. K. (2020). Security, privacy and risks within smart cities: Literature review and development of a smart city interaction framework. Information Systems Frontiers, 1–22.

Jeffery, C. R. (1969). Crime prevention and control through environmental engineering. Criminologica, 7, 35.

Jeffery, C. R. (1977). Crime prevention through environmental design. Sage Publications.

Johnson, S. D., Guerette, R. T., & Bowers, K. (2014). Crime displacement: What we know, what we don’t know, and what it means for crime reduction. Journal of Experimental Criminology, 10, 549–571.

Kleemans, E. R. (2018). Organized crime and places. In G. J. N. Bruinsma & S. D. Johnson (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of environmental criminology (pp. 868–882). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190279707.013.24

Kleemans, E. R., Soudijn, M. R., & Weenink, A. W. (2012). Organized crime, situational crime prevention and routine activity theory. Trends in Organized Crime, 15(2-3), 87–92.

Lemieux, A. M. (Ed.). (2014). Situational prevention of poaching. Routledge.

Loeber, R., & Farrington, D. P. (2000). Young children who commit crime: Epidemiology, developmental origins, risk factors, early interventions, and policy implications. Development and Psychopathology, 12(4), 737–762.

Maheshwari, B., Pinto, U., Akbar, S., & Fahey, P. (2020). Is urbanisation also the culprit of climate change? Evidence from Australian cities. Urban Climate, 31, 100581.

Milivojevic, S., & Radulski, E. M. (2020). The “future internet” and crime: Towards a criminology of the internet of things. Current Issues in Criminal Justice, 1–15.

Miró Llinares, F., & Johnson, S. D. (2018). Cybercrime and place: Applying environmental criminology to crimes in cyberspace. In G. J. N. Bruinsma & S. D. Johnson (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of environmental criminology (pp. 883–906). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190279707.013.39

Netacea. (2022). Refund fraud as a service: The other RaaS threat for retailers. Netacea.

Newman, G., & Clarke, R. (2003). Superhighway robbery: Crime prevention and e-commerce. Willan Publishing.

Pires, S., & Clarke, R. V. G. (2011). Are parrots craved? An analysis of parrot poaching in Mexico. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency.

Ratcliffe, J. H. (2006). A temporal constraint theory to explain opportunity-based spatial offending patterns. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, 43(3), 261–291.

Robertson, A. L., Harris, D. A., & Karstedt, S. (2023). “It’s a preventable type of harm”: Evidence-based strategies to prevent sexual abuse in schools. Child Abuse & Neglect, 145, 106419.

Sampson, R., Eck, J. E., & Dunham, J. (2009). Super controllers and crime prevention: A routine activity explanation of crime prevention success and failure. Security Journal, 23(1), 37–51.

Schmid, C. F. (1960a). Urban crime areas: Part I. American Sociological Review, 25(4), 527–542.

Schmid, C. F. (1960b). Urban crime areas: Part II. American Sociological Review, 25(5), 655–678.

Schneider, J. L. (2008). Reducing the illicit trade in endangered wildlife: The market reduction approach. Journal of Contemporary Criminal Justice, 24(3), 274–295.

Shaw, C. R., & McKay, H. D. (1969). Juvenile delinquency and urban areas: A study of rates of delinquency in relation to differential characteristics of local communities in American cities. University of Chicago Press.

Summers, L., & Guerette, R. T. (2018). The individual perspective. In G. J. N. Bruinsma & S. D. Johnson (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of environmental criminology (pp. 84–104). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190279707.013.3

Taylor, R. B. (2018). How do we get to causal clarity on physical environment-crime dynamics? In G. J. N. Bruinsma & S. D. Johnson (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of environmental criminology (pp. 58–83). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190279707.013.2

Thiault, L., Weekers, D., Curnock, M., Marshall, N., Pert, P. L., Beeden, R., Dyer, M., & Claudet, J. (2020). Predicting poaching risk in marine protected areas for improved patrol efficiency. Journal of Environmental Management, 254, 109808.

Tompson, L., & Coupe, T. (2018). Time and opportunity. In G. J. N. Bruinsma & S. D. Johnson (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of environmental criminology (pp. 691–715). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190279707.013.19

Van Hardeveld, G. J., Webber, C., & O’Hara, K. (2016). Discovering credit card fraud methods in online tutorials. Proceedings of the 1st International Workshop on Online Safety, Trust and Fraud Prevention, 1–5.

Wang, F., & Topalli, V. (2024). The cyber-industrialization of catfishing and romance fraud. Computers and Human Behavior, 154, 108-133. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2023.108133

Weekers, D., Petrossian, G., & Thiault, L. (2021). Illegal fishing and compliance management in marine protected areas: A situational approach. Crime Science, 10(1), 9.

Welsh, B. C., & Taheri, S. A. (2018). What have we learned from environmental criminology for the prevention of crime? In G. J. N. Bruinsma (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of environmental criminology (pp. 757–776). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190279707.013.31

White, R., & Cunneen, C. (2006). Social class, youth crime and justice. Youth Crime and Justice, 17.

Wortley, R., & Townsley, M. (2017). Introduction. In R. Wortley & M. Townsley (Eds.), Environmental criminology and crime analysis (2nd ed., pp. 1–26). Routledge.

…

…

- Want to learn more about Ron Clarke? Check out this podcast with Professor Jerry Ratcliffe of Temple University to learn more about Professor Clarke’s career and contributions to the field. ↵

- When you see NB in a document, it means to take special note. It is the Latin abbreviation for nota bene, which translates into “note well” or pay attention! ↵

- Diffusion of benefits is the observation of crime prevention impact in areas not directly targeted by an intervention (sometimes called the “halo effect”). For example, imagine that better streetlights are installed in a particular high-crime neighbourhood. While this results in reduced crime rates in the streets with new lighting, declines may also be observed in adjacent neighbourhoods, even though those areas did not receive the lighting upgrades. Potential reasons might include criminals perceiving increased risks in surrounding areas due to the interventions or a general community uplift that affects broader areas than just the targeted location. ↵

A perspective in criminology that views criminal behaviour as the outcome of deliberate choices made by individuals after weighing the potential benefits and costs of their actions.

A theory that suggests crime occurs when a motivated offender, a suitable target, and the absence of a capable guardian converge in time and space.

A theory that suggests crimes are not randomly distributed but rather form patterns influenced by the daily activities and routines of potential offenders and the spatial layout of the environment.

Aa multidisciplinary approach to deterring criminal behaviour through urban and environmental design that enhances natural surveillance, reinforces territoriality, controls access, and maintains environments.

Strategies aimed at reducing crime by modifying the physical or social environment to decrease opportunities for criminal behaviour.