6 Cultural Theories of Crime: The Chicago School and Social Disorganisation

Shannon Walding

Learning Objectives

- Explain the background to theories about neighbourhood structure, including data-driven social research, social upheaval, and the concentric circles urban model.

- Introduce Shaw & McKay’s theory of social disorganisation.

- Explore extensions to the theory, particularly the systemic model and collective efficacy, and consider the theory’s ongoing application to social understanding.

Before You Begin

- Think about a place in your community that you feel safe. What makes it feel safe to you?

- Think about a place that you consider to be unsafe. Is this a place you have visited? If not, why do you think it is unsafe? If you have, what are the things that make it feel unsafe to you?

- Can you think of a suburb, town, or postcode in your area that has a stereotype about the people who live there? Where do you think this stereotype came from? If you had to be honest with yourself, do you believe the stereotype? Why or why not?

INTRODUCTION

Social disorganisation theory is a criminological theory of place. Instead of focusing on what kinds of people commit crime, social disorganisation theorists focus on the kinds of places that offenders come from. As a result, this is a macro theory, also known as a structural theory: an attempt to explain why particular groups seem to offend more than others. In this case, people are grouped according to their neighbourhood.

Some places clearly experience more crime and have more people identified as offenders than other places, so there must be something about a place that can explain crime – and when we think about that kind of place, we often think of urban poverty. Consider the HBO series The Wire in its depiction of the American city of Baltimore in the first decade of the 21st century[1]. Through telling the stories of people in the inner city affected by social change that led to job loss and depopulation, the writers of The Wire demonstrated how political, economic and social factors work together in a city to create disadvantage and limit the choices of its inhabitants depending on where and to whom they were born (Chaddha & Wilson, 2011). The Wire’s complex depiction of systemic urban inequality in the city over five seasons clearly demonstrated that “the actions, beliefs, and attitudes of individuals are shaped by their context” (Chaddha & Wilson, 2011, p.165).

Social researchers predating The Wire by one hundred years were also interested in explaining how context influenced crime, because they could see that individual explanations couldn’t explain how crime clustered. From origins in sociologist Emile Durkheim’s ideas about anomie and a famous group of sociologists called the Chicago School came a theory that treated social issues like crime as if they were a disease afflicting some parts of a city. Social disorganisation theory has undergone many developments since its inception in 1942 but continues to be one of the most influential theories in criminology.

HISTORICAL CONTEXT

The context for the development of social disorganisation theory is in many ways related to the social conditions of Chicago in the first part of the 20th century. Researchers who made up the famous Chicago School, the sociology department at the University of Chicago that was established in 1892, found themselves living and working in a city where an already-rapidly growing population then tripled in size again by 1930. Rapid industrialisation and the need for unskilled labour meant many immigrants settled in Chicago in successive waves from different places in Europe and other places in the United States, leaving behind support networks, settling into a new urban environment with limited infrastructure.

Communities looked very different from the small, close-knit small towns that many Chicago residents would have grown up in. Think of it as comparing life in the TV show Little House on the Prairie to life in the movie Gangs of New York. In 1920, Chicago had a population of around 2.7 million people; in some places, the population density was more than 19,000 people per square kilometre (University of Chicago, 1934). The city of Sydney in the same year had a population of 828,700 (“Sydney’s population”, 1920). Major urban cities around the world would have been crowded, smelly, sooty, and full of people with different religions, languages, and even traditional foods, but Chicago’s extreme industrialised growth and immigration made it a special example. At the peak of the rapid change, the Great Depression in the 1920s meant that many people without means or stability were left unemployed, with overcrowding, poor housing and sanitation, resident displacement and no way to improve their situation. The Chicago School’s sociologists saw the resulting range of social conditions including criminal activity and took inspiration from the ideas of European researchers Andre-Michel Guerry, Lambert Quetelet and Emile Durkheim.

French astronomer, mathematician, statistician, and sociologist Lambert Adolphe Jacques Quetelet is often credited (among other significant contributions) as one of the first to use statistics and probability to understand human behaviour; however, he was preceded in this by another Frenchman, lawyer Andre-Michel Guerry. Guerry’s Essai sur la Statistique Morale de la France, presented to the Académie Française des Sciences in 1833(/2002), demonstrated the concentration of criminal activity in some areas of France compared with others, and particular times compared with others (Friendly, 2022). Using quarterly data obtained from French criminal prosecutors, he related the outcomes of crime and suicide occurrence to social variables like whether an area was agricultural or manufacturing, wealthy or poor (Sampson, 2012), thus becoming one of the first scholars to re-orient thinking about criminal behaviour from solely the result of individual responsibility to acknowledging the role of society.

Following closely behind, Quetelet advocated for the use of collecting and aggregating data about people to better understand trends and patterns in society. When examining Paris and other urban centres in France at the beginning of the 19th century, as well as comparing France to Belgium and the Netherlands, Quetelet identified that the number of people accused and convicted of crimes remained constant within different geographical areas. While he identified several potential correlations between individual characteristics and crime, such as being young, male, poor, undereducated, and unemployed, he also noted that some of the poorest areas of France were the safest, despite high rates of illiteracy and other markers of poverty. Through these observations, he began to argue that “the crimes which are annually committed seem to be a necessary result of our social organization… ” (Quetelet, 1842, p.108).

Researching social dynamics from the University of Bordeaux in the late 19th century, Emile Durkheim then sought to understand why geographic areas and social groups have consistent rates of suicide over time. In his influential book Suicide, he writes:

…individuals making up a society change from year to year, yet the number of suicides itself does not change…the population of Paris renews itself very rapidly, yet the share of Paris in the total number of French suicides remains practically the same… The causes which thus fix the contingent of voluntary deaths for a given society…must then be independent of individuals… (Durkheim, 1897/1952, p.307)

On discovering that a similar consistency in suicides existed among married people compared with unmarried and military compared with non-military, Durkheim examined the patterns of suicide incidence and theorised that social integration based on religion, family, and work was the key explanatory factor for why people suicided . His theory suggested that social integration was much more important than individual characteristics or illness. In combination with his other extremely influential work of the time, The Division of Labor (1893/1964), Durkheim’s findings led him to believe that without social integration influencing the development of shared values and attitudes, deviant behaviour would result. His point was that coming from a particular place or group influenced our behaviour, perhaps even more than our individual characteristics.

Like Quetelet before them, the Chicago School sociologists relied on the use of statistics to help them identify and classify the problems in the city; and like Durkheim, they believed our social conditions explain our behaviour. Many of the statistics they analysed came from traditional forms of official data (crime records, census reports, and data from administrative agencies, such as housing and welfare). One pair of sociologists in particular, Robert Park and Ernest Burgess, took the approach that humans, like animals or plants, could be studied in their “natural habitat”; but instead of a forest or a lake, people naturally appear in neighbourhoods. In time, the term “social ecology” became to characterise the ideological premise that the important level of observation for human behaviour is at the neighbourhood or community level, and the contributions of the Chicago School are considered part of the ecological school of criminology (Williams, 2012).

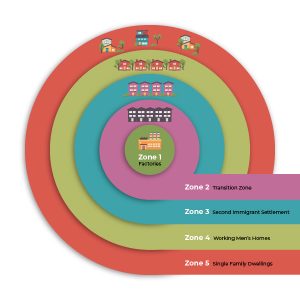

Park and Burgess (1925/1967) famously conceptualised the city as a series of concentric zones that radiated outwards from the centre (shown in Figure 6.1). The inner circle, or first zone, was that of the central business district (CBD) and was characterised at the time by places of business like factories and warehouses. The second zone was called the interstitial zone. Also known as the “zone of transition,” this was the part of the city where residents newly arrived to the city, whether from small country towns or from other countries, could afford to live. Rents were cheap but came at a high price. Buildings were crowded and in disrepair, sanitation almost non-existent, and many family members would have to live together in small rooms while working long hours in order to be able to afford to keep a roof over their heads. The reason Zone 2 is called the zone of transition is because people were constantly moving in and out. Those who could afford to move to the outer suburbs of the city did as soon as they were able, but they were quickly replaced by a non-stop stream of new residents hoping to try their luck in the cities during the Industrial Revolution.

The concentric zone model, developed by Park and Burgess (1925) conceptualises the city in concentric zones. Image by the authors.

Park and Burgess identified that with each subsequent zone, rents became more expensive, conditions improved, and crime rates declined. The further someone went from the centre of the city, the safer, cleaner, and more expensive the neighbourhoods. As subsequent sociologists began to adopt this view of how cities grew, they found that several social ills followed a similar pattern. Fellow Chicago School sociologists Clifford Robe Shaw and Henry D. McKay identified this pattern for rates of delinquency, tuberculosis, and infant mortality (1931). Of particular interest is that Shaw and McKay identified similar patterns in 20 other American cities, leading them to conclude that the experience of a high crime interstitial zone was universal (Snodgrass, 1976).

If the experience of a high crime zone of transition was universal, so was the experience of lower crime outer zones. Over time, the people who lived in the zone of transition changed; people came and went. Patterns of movement among immigrant and ethnic groups varied by city but the outcome remained the same: the zone of transition was one of high levels of health, social, and crime issues no matter who lived there, just as Durkheim found that the pattern of suicide was the same no matter which individuals were living in Paris. The task then was to understand how criminality, previously thought only to be the fault of the individual, was explained by community experiences. And Chicago School theorists were the best people suited for the challenge.

THEORY DESCRIPTION

Social disorganisation

Park and Burgess used the term social disorganisation to describe the physical and social deterioration of the inner concentric zones as people moved through and further away from the CBD (Kubrin & Mioduszewski, 2019). Where Durkheim had identified lack of social integration as key to social problems in a neighbourhood, Thomas and Znaniecki (1927) and fellow Chicago School sociologist Wirth (1938) proposed that integration was influenced by ethnic heterogeneity (or differences) along with population density (Sampson, 2012).

It was Park and Burgess’ colleagues Shaw and McKay (1942) who, with their interest in juvenile delinquency, theorised a connection to crime. They examined official court and police data as well as studying juveniles in their neighbourhoods and discovered that patterns of delinquency followed the patterns of what Park and Burgess had termed social disorganisation: high residential mobility, disruption in families, decaying neighbourhoods, and low socio-economic status. They also identified a range of health issues that followed similar geographical patterns.

The original theory

Social disorganisation theory was how Shaw and McKay (1942/1969) then tried to explain the link between the social conditions of the neighbourhood and crime. The population turnover and ethnic heterogeneity in interstitial areas of the city were assumed to make social organisation difficult in those areas, as the authority of institutions like family and church were diminished. They theorised that when neighbourhoods are disorganised, the breakdown in social ties means that residents can no longer exercise informal social control. Informal social control is how a society socialises people to commonly held values and norms, by setting standards and intervening in problems (Bursik, 1988; Kubrin & Weitzer, 2003), and failures of neighbourhood informal social control mean juveniles and young adults then choose to behave in antisocial ways. Shaw & McKay reasoned that a delinquent tradition would be established in those areas where social disorganisation became established; the community’s inability to regulate itself would lead to entrenched criminal behaviour. In this way, Shaw and McKay’s work also influenced the development of social control theories (see chapter 8) and social learning theories (see chapter 10).

Shaw and McKay’s social disorganisation theory proposed that socially disorganised neighbourhoods were characterised by three structural conditions (Gehring & Batista, 2018):

- Low socio-economic status: people lived in poverty and had few resources.

- Ethnic heterogeneity: people came from a multitude of different ethnicities, cultures, and religions, and therefore tended to isolate themselves from each other.

- Residential instability or mobility: many people move into and then out of the area as they either have trouble maintaining somewhere regular to live or look to find somewhere better as soon as possible.

They concluded that these conditions meant that some areas of the city would have high crime rates no matter who lived there.

Importantly, they were not suggesting that poverty caused crime: they were instead identifying characteristics of neighbourhoods, including high levels of delinquency, all of which develop through interaction with each other, in keeping with their ecological approach (Bursik & Grasmick, 1993). However, that ecological approach, with its focus on concentric zones and a proposed ‘natural’ process of people’s movement, struggled as society and the structure of the city changed over time.

Shaw and McKay’s work also suffered from the difficulties other researchers had in interpreting it effectively, where social disorganisation itself was not clearly differentiated from its theorised outcome of delinquency or crime, or the structural conditions that gave rise to it. Of course, crime was only one of a range of theorised outcomes of social disorganisation, all of which were speculated to be related to each other and simultaneously causes of further social disorganisation, as part of the ecology of a neighbourhood. You can see from the explanation so far of social disorganisation itself and the theory, that it isn’t clear exactly what social disorganisation itself is, or how it might be measured. Shaw and McKay’s work needed clarification and more flexibility as times changed, and as a result was sometimes popular and sometimes unpopular throughout the rest of the 20th century. Several key developments of their theory resulted, following on from the clarifications provided in the important work of Kornhauser (1978).

Clarification

Kornhauser (1978) stepped out the differentiation between concepts in Shaw and McKay’s social disorganisation theory, pointing out that for the theory to work, the structural conditions needed to result in a breakdown of people’s social ties and narrowing of their social networks, which would then affect their ability to exercise social control. She was less interested in the idea of cultural transmission that made up the other part of the theory. If social disorganisation is conceptualised as “the inability of local communities to realize the common values of residents or solve commonly experienced problems” (Bursik, 1988, p.521, referencing Kornhauser, 1978, p.63), then social disorganisation theory explains how that inability results in increased levels of crime.

Kornhauser and others explained that communities with low SES, ethnic heterogeneity, and residential instability will have weaker social ties to each other and weaker capacity for guardianship. This happens because (Bursik, 1988):

- People want to leave the area quickly, so they are not invested in community institutions;

- Because people move in and out so often, it is difficult to establish solid relationships between residents with similar priorities (such as parents of local children, or people with multiple generations living in the area);

- When people are ethnically and culturally different from each other, communication is difficult.

The result is a socially disorganised neighbourhood where adults are less likely to supervise youth, regulate public behaviour, or report crime or deviance to authorities. A tolerance for deviance and crime develops in the area because residents do not exercise effective informal social control, that is, by ensuring a collective pursuit of shared values (Sampson, 1987). These clarifications helped researchers to develop the theory further, to fit with different social and geographical structures other than Chicago in the first half of the 20th century. In particular, the effects of deindustrialisation on the cities of the USA and other rapid social change such as civil rights transformation through the 1970s meant that those who could afford to leave inner city neighbourhoods did (Bellair, 2017). Instead of quick turnover of people arriving to the city, saving money, and moving to the suburbs, disadvantaged Americans became stuck in inner city neighbourhoods that were increasingly isolated (Wilson, 1987), necessitating a review of how social disorganisation worked.

DEVELOPMENTS

The systemic model

Modern formulations of social disorganisation theory are based on a systemic model, emphasising that neighbourhoods consist of overlapping personal and institutional social networks that are necessary for the community to be able to organise (Bursik, 1988). Social organisation could be defined as “a complex system of friendship and kinship networks rooted in family life and ongoing socialization processes” (Kasarda & Janowitz, 1974, p.329). According to the systemic model, as long as interpersonal networks are dense and overlapping, a neighbourhood should be able to achieve commonly held goals, like keeping residents safe and positively socialising youth. That meant that researchers looked to measure the networks within a community as indicators of whether a community was organised or disorganised.

People’s capacity for organisation as a group is tied up with the institutions within their neighbourhoods, so the social networks of people in a neighbourhood need to include local institutions, and institutions need to be connected to each other. The ability of institutions like schools and churches to serve, unify, and mobilise their community is theorised to be crucial to avoiding both the development of social disorganisation and its consequences. This train of thought is related to ideas of social capital (Bursik, 1999) and influences social bonds theorising (a micro-level theory: see Cattarello, 2000). Kornhauser (1978) referred to these as horizontal links within a community.

Bursik[2] and Grasmick (1993) recognised that social disorganisation within a neighbourhood did not take place within a vacuum, and decisions taken outside the neighbourhood affecting employment, education, and criminal justice (the most relevant at the time being the War on Drugs which began an exponential rise in the people sent to prison) would influence the structural characteristics affecting the capacity of neighbourhoods to organise. They emphasised a community’s vertical links in their social networks, links to institutions outside the community that would allow the neighbourhood to access resources and assistance (Sampson, 2011). However, addressing macro-structural conditions like poverty and inequality is also important for neighbourhood organisation (Kubrin & Tublitz, 2023), and these are processes that communities are not able to influence.

Importantly, the strength and breadth of social ties within neighbourhoods is considered to be essential to the ability to mobilise informal social control (Kubrin & Weitzer, 2003). These include local friendship networks and engagement in informal community socialisation as well as more formal community organisations (Bursik, 1988). These ties are assumed to naturally lead to a community exercising informal social control, but the existence of networks of ties did not necessarily mean that anti-crime goals were addressed. The social networks in a community might not only include law-abiding people, and even if they did, these networks might not be effective in generating action for attaining community goals (Kubrin and Weitzer, 2003).

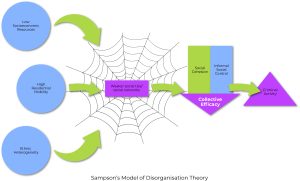

Collective efficacy

Robert Sampson developed the theory further, focusing on the next mechanism working between social disorganisation in a neighbourhood and crime in that neighbourhood, that of willingness and ability to activate informal social control. Sampson along with his colleagues Raudenbusch and Earls (1997) developed his conceptualisation by emphasising the agency of people within neighbourhoods. According to Sampson, collective capacity for social action is more important than density of social networks for crime control.

While social ties and social networks might work either for or against informal social control, Sampson emphasised the community’s capacity to activate their social networks for commonly desirable goals, a concept he labelled collective efficacy. The ability to live safely in your home and in your streets is assumed to be a commonly desirable goal, and Sampson specifically points out that the ability to exercise social control to achieve that is not necessarily dependent on close friendships in a neighbourhood, just working trust and social interaction (Sampson, 2009). Evidence found by Morenoff, Sampson, and Raudenbusch (2001) indicates that even when social ties are weak, strong collective efficacy is related to lower neighbourhood crime. Sampson also emphasises that collective efficacy is a task-specific construct: that is, the neighbourhood might be ineffective at mobilising their social connections to achieve some tasks, but effective at other tasks, so the key is to achieve collective efficacy in enacting social control over disorder and crime specifically (Sampson, 2011), seen in Figure 6.2[3].

Robert Sampson’s model of disorganisation theory. Image by the authors. Long description

These extensions of social disorganisation theory clarify the pathway through which neighbourhood characteristics are proposed to lead to crime by articulating measurable concepts. They also set neighbourhoods within their context. Modern social disorganisation theorists recognise that these neighbourhood processes are not natural, as initially proposed, but can be influenced both within and outside of neighbourhoods. That means that the development of disorganisation and the mechanisms by which it leads to crime can be affected by policy and by programs.

THEORY APPLICATION

Theory Application to Other Contexts

While the formulation of social disorganisation theory is aimed at explaining offender rates in neighbourhoods, it has also been applied to victimisation rates, and to explain occurrence of disorder. It has also been examined in relation to specific types of crime, like intimate partner violence, and for different groups of people, like Indigenous and First Nations peoples. It has been applied where instead of overcrowding of clashing cultures, neighbourhoods have instead experienced an emptying out as industry departed and the Global Financial Crisis of 2008 meant that people could no longer afford their homes, leaving them empty. Where there are not enough people to form effective social networks, collective efficacy is as difficult as when people in a community have communication issues. It has also been tested in rural areas, and where inner city neighbourhoods experience mobility not due to choice but because of mass incarceration. While social disorganisation was initially suggested by its critics to be limited only to inner city Chicago, researchers have in fact been able to apply tenets of the theory all over the world in different ways (see Wickes & Sydes (2017) for an entry into the literature). What follows are some examples of the application of social disorganisation theory.

Community Intervention Applications of Social Disorganisation Theory

The Chicago Area Project, or CAP, was created by Clifford Shaw in the 1930s in response to and alongside his research. His goals were to influence the organisation of communities and particularly the lives of juveniles, intending to disrupt the effects of social disorganisation. The CAP could be seen as the first community anti-crime program, where community centres were set up and run by local residents with assistance from and engagement with other community organisations like schools, churches, law enforcement, and local government through funding (Berger et al, 2005). Wide ranging and long lasting (some projects lasted for over 50 years!), the CAP created community assistance and worked from the bottom up, but emphasised coping with the structural problems neighbourhoods were subject to by wider social injustice without changing the situation (Williams, 2012). The CAP predated the systemic model, and while it worked to strengthen and use what would eventually be termed horizontal and vertical ties, there was no attempt to influence macro-structural conditions like poverty or social injustice.

There was no real evidence of effects on criminality from the original programs, but the projects did provide a great deal of assistance to communities that were struggling. Creating evidence of outcomes of community projects is extremely difficult, especially when implementations are wide ranging and don’t have research designs and data collection attached specifically to the intervention. The intention of these projects was to change something about the neighbourhood; in this case, facilitating and empowering residents in altering the level of disorganisation in their neighbourhood. In this way, the CAP worked at the appropriate level of intervention: because social disorganisation theory is a theory about communities, interventions should be with communities rather than trying to treat or change individuals.

Contemporary community interventions aimed at crime prevention share DNA with the original Chicago Area Project. Programs that centre community decision-making and action, often termed ‘grass roots’ programs, and target issues like social ties, collective efficacy, and informal social control, they can be viewed as being based in social disorganisation theory (Kubrin & Tublitz, 2023). Kubrin and Tublitz (2023) identify community violence outreach programs, community-based mentoring and after-school programs for youth, and place-based improvements to the physical environment as interventions that align with the theory. While they find that community violence outreach programs have mixed results, they have been found to affect social trust and community attitudes about violence. Youth programs that target the creation of prosocial ties for young people within their communities and physical interventions intended to increase the prosocial use of space (one example in Australia might be the government propensity for building skate parks in recent years!) are also identified as in keeping with the social disorganisation framework.

Coercive Mobility Theory

Researchers have also applied the work of social disorganisation theorists to related social problems, as in the case of coercive mobility theory, created by Dina Rose and Todd Clear[4] (1998). Rose and Clear considered the structural conditions proposed by Shaw and McKay, those of low socio-economic status, high mobility, and heterogeneity of people, in the context of rapidly rising imprisonment rates in the United States through the 1980s and 1990s. They saw that rising imprisonment was not evenly spread across neighbourhoods, but instead concentrated in some neighbourhoods in the same way that Shaw and McKay initially observed among Chicago juvenile delinquents. They proposed that the high levels of movement of residents of those neighbourhoods, caused both by the removal and return of people going to prison and the movement of their families who experienced differing circumstances and moved accordingly, as creating the same kind of community results as in social disorganisation theory. In the case of concentrated imprisonment, however, mobility was coerced rather than natural as the original Chicago theorists believed.

In this kind of community, the forced removal, absence and return of predominantly men could cause harmful disruptions to social relationships in communities. In addition, returning prisoners in communities where networks are already under strain place additional burdens on local services that provide support. These disruptions to social relationships are thought to result in a range of adverse outcomes in high-imprisonment communities, including increases in crime. There is evidence for some, but not all, theoretical linkages proposed in coercive mobility theory. Existing research has indeed shown that, at least in the United States, there is a community-level association between high prison entry/community re-entry rates and crime (Clear, 2009; Hipp & Yates, 2009; Drakulich et al, 2012; Chamberlain & Boggess, 2018). Existing work has also shown that communities with very high rates of imprisonment experience an escalation of other problems, including increased violence (Renauer & Cunningham, 2006; Vieraitis et al, 2007), poverty and inequality (Western, 2007; Defina & Hannon, 2013), and mistrust in the law (Muller & Schrage, 2014).

Case Study: Comparative crime rates in the Torres Strait

Having discovered that reported rates of crimes against the person and domestic violence breaches were lower in the Torres Strait than in other relatively isolated Indigenous communities in Queensland, and that property crime rates were lower in the Torres Strait than in Queensland as a whole, Staines and Scott (2020) examined historical and anthropological evidence to try to explain why. They determined that the experience of colonisation had been different in the Torres Strait from mainland Aboriginal communities in some important ways, likely because of geographical isolation and difficulty of governance by an outside power:

- Torres Strait Islanders maintained levels of autonomy and self-governance throughout colonisation. That meant that the communities in the Torres Strait maintained structures of informal social control, social cohesion and collective efficacy.

- Mainland Aboriginal communities experienced frontier violence, dispossession, and displacement to a much higher degree than Torres Strait Islanders. This meant that communities in the Torres Strait were much less likely to be subject to the kind of anomic conditions theorised by Durkheim (see Chapter 5) to influence individual behaviour, and they also maintained relative less heterogeneity of background and population turnover than mainland Indigenous communities.

The resulting structural differences in Torres Strait communities compared with mainland Queensland Aboriginal communities are explained by social disorganisation theory as resulting in less social disorganisation, greater levels of informal social control, and therefore lower levels of crime. Staines and Scott (2020) do point out, however, that their crime findings were based on reported crime, and the social and geographical conditions in the Torres Strait might well result in both underreporting of crime and under-policing (the Torres Strait has a long history of community policing, which may result in fewer formal reports). They are explaining their statistical finding using social disorganisation theory, but that statistical finding should be considered in terms of how crime is measured in their study.

THEORY CRITICISMS

Some limitations of social disorganisation theory, like the tendency of Shaw and McKay to use crime and delinquency as both an indicator that a neighbourhood was disorganised and an outcome of social disorganisation, have been addressed through developments of the theory. However, those developments have generated further lack of precision regarding the boundaries between the proposed intervening concepts of social ties, collective efficacy, and informal social control. Kubrin and Weitzer (2003) called for clearer conceptualisation (for example, where is the boundary between social ties and collective efficacy, and if we’re measuring both, how do we differentiate between them?) and importantly, consistency in measurement of those concepts in social disorganisation research. Researchers have measured these concepts, as well as the structural neighbourhood conditions like mobility and heterogeneity, in a great many different ways, making it difficult to pin down evidence for or against the theory in different contexts.

Another criticism of social disorganisation theory has roots in its original development through examination of official data. Researchers in the area have traditionally used official criminal activity records to determine where offenders were concentrated, but over-policing in some neighbourhoods (particularly those where people are not well off) and the effect of a person’s neighbourhood on the decisions of police and courts are likely to make it look like people from some neighbourhoods commit more crimes (Kubrin & Mioduszewski, 2019). Because social disorganisation theory also doesn’t really address occupational or institutional crime, but instead focuses on street crime, the theory has been accused of commingling crime with poverty. As a result, researchers beginning with Sampson & Groves in 1989 have used victimisation, self-report, and social surveys to construct measurements for neighbourhoods that don’t rely on policing activity[5]. Along with the addition of the concept of collective efficacy, the evidence for social disorganisation theory has therefore been able to grow beyond a simple relationship between socio-economic status and crime.

What constitutes a neighbourhood is also an ongoing issue for social disorganisation research. Availability of data means that researchers are often restricted to using political or administrative boundaries of places (Sampson et al, 2002), but these aren’t necessarily what people would consider to be their neighbourhood, or even have similar structural conditions across the space. Gerell (2015) identified three different perspectives in the criminology literature, labelling them neighbourhood, micro-neighbourhood and micro-place. The results of his case-study research comparing collective efficacy measurements across size of neighbourhood prompted him to suggest that more attention should be paid in research to micro-places because they seem to represent more closely what people consider their neighbourhood, but this might not always be possible.

FUTURE DIRECTIONS

As a theory that grew from the study of a very specific place and time, the question of the applicability of social disorganisation theory across contexts has always been important. The developments of the theory beyond the concentric circles model and with greater distinction between concepts helped to address cross-applicability concerns, and the concepts behind the theory have endured as they have been applied in different contexts. A meta-analysis by Pratt & Cullen (2005) examined the evidence for macro-level theories, and found strongest evidence for collective efficacy as a structural explanation for crime. The collective efficacy formulation of social disorganisation theory also appears to perform well across different cultures and locations, suggesting that this perspective will continue to play a large role in study of neighbourhood effects on crime in the future (Bellair, 2017). However, researchers remain concerned about differences in results in western European nations compared with the US, suggesting that adaptations to theory to take into account fundamental cultural differences is necessary (Pauwels et al, 2018).

Researchers are also becoming more interested again in the cultural transmission element of Shaw and McKay’s original formulation, an area that had been somewhat neglected in the renaissance of the theory (Kubrin & Mioduszewski, 2019). Meanwhile, evidence of high crime rates leading to low collective efficacy or low informal control (rather than the other way around) has increased interest in the idea of reciprocal effects (Bellair, 2017). This is where crime is not just the outcome of the process but in fact is another stepping stone in ongoing neighbourhood processes that feed into each other in a circular way: structural conditions lead to breakdowns in social ties and hampered collective efficacy which lead to higher crime, which in turn leads to people being wary of each other and further breakdowns in efficacy and ties, for example. More advanced data collection and analysis methods should lead to further developments in the theory along those lines. Lastly, evidence in contemporary communities strongly suggests that immigration and subsequent heterogeneity of background in a community is not related to more crime, meaning that theorists need to rethink how immigration affects the organisation of neighbourhoods (Kubrin & Mioduszewski, 2019).

CONCLUSION

Social disorganisation theory, while controversial in its original formulation, has gone on to be one of the most influential theories in criminology. While its origins rested in a theory about concentric circles of types of neighbourhoods in Chicago, contemporary formulations of the theory focus on the systemic nature of neighbourhoods: how the internal and external institutions of a community interact with people’s social ties and capacity for influencing behaviour to result in a range of social outcomes including crime levels. In addition, these days, it is not simply accepted that neighbourhoods be subjected to poor structural conditions. Instead, researchers and community organisations recognise that change must be driven not just by community action, but also by political action.

However, recognition of the contextual and processual nature of the theory does not make it any easier to test, so evidence for and refinement of the processes described in the theory will need to continue to be worked on by researchers for some time to come. New ways of collecting data and measuring concepts, as well as new ways of conceptualising the theory’s mechanisms in different settings, will allow social disorganistion theory to continue to grow and change along with society. Meanwhile, social disorganisation theory has influenced and been influenced by many other fields of criminological study, and is a theory that can and should work in partnership with other theories to explain behaviour.

Check Your Knowledge

Discussion Questions

- What are the three main factors that the original scholars of social disorganisation theory attributed to crime rates in certain neighbourhoods?

- What is collective efficacy and how can it be leveraged to create structural changes within a neighbourhood or community?

- What are some ways that social disorganisation can be used to create programs and policies to help reduce crime and deviance?

REFERENCES

Bellair, P. (2017). Social disorganization theory. In Oxford research encyclopedia of criminology. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190264079.013.253

Berger, R., Free, M. & Searles, P. (2005). Crime, justice, and society: An introduction to criminology. Lynne Rienner Publishers. https://doi.org/10.1515/9781685858674

Bursik, R. J. (1988). Social disorganization and theories of crime and delinquency: Problems and prospects. Criminology, 26(4), 519-552. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-9125.1988.tb00854.x

Bursik, R. J. (1999). The informal control of crime through neighborhood networks. Sociological Focus, 32(1), 85–97. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20832020.

Bursik, R. J., Jr., & Grasmick, H. G. (1993). Neighborhoods and crime: The dimensions of effective community control. Lexington Books.

Chaddha, A., & Wilson, W. J. (2011). “Way Down in the Hole”: Systemic urban inequality and The Wire. Critical Inquiry, 38(1), 164-188. https://doi.org/10.1086/661647.

Durkheim, E. (1893/1964). The Division of Labor in Society. Free Press.

Durkheim, E. (1897/1952). Suicide. Free Press.

Friendly, M. (2022). The life and works of André-Michel Guerry, revisited. Sociological Spectrum, 42(4-6), 233-259. https://doi.org/10.1080/02732173.2022.2078450

Gerell, M. (2015). Collective efficacy, neighborhood and geographical units of analysis: Findings from a case study of Swedish residential neighborhoods. European Journal on Criminal Policy And Research, 21, 385-406.

Guerry, A.-M. (2002). Essai sur la statistique morale de la France (H.P. Whitt & V.W. Reinking, Trans.). Edwin Mellen Press. (Original work published 1833)

Gehring, K. S. & Batista, M. R. (2018). Social disorganization theory (Ser. Crimcomics, 4). Oxford University Press.

Cattarello, A.M. (2000). Community-level influences on individuals’ social bonds, peer associations, and delinquency: A multilevel analysis. Justice Quarterly, 17(1), 33-60, https://doi.org/10.1080/07418820000094471.

Chamberlain, A.W. & Boggess, L.N. (2019). Parolee concentration, risk of recidivism, and the consequences for neighborhood crime. Deviant Behavior, 40(12), 1522-1542. https://doi.org/10.1080/01639625.2018.1540574.

Clear, T. R. (2009). Imprisoning communities: How mass incarceration makes disadvantaged neighborhoods worse. Oxford University Press.

DeFina, R., & Hannon, L. (2013). The impact of mass incarceration on poverty. Crime & Delinquency, 59(4), 562-586.

Drakulich, K., Crutchfield, R., Matsueda, R., & Rose, K. (2012). Instability, informal control, and criminogenic situations: community effects of returning prisoners. Crime, Law, and Social Change, 57(5), 493–519.

Hipp, J.R., & Yates, D.K. (2009). Do returning parolees affect neighborhood crime? A case study of Sacramento. Criminology 47(3), 619–56.

Kasarda, J. D., & Janowitz, M. (1974). Community attachment in mass society. American Sociological Review, 39, 328– 329.

Kornhauser, R. (1978). Social sources of delinquency. University of Chicago Press.

Kubrin, C. E., & Mioduszewski, M. D. (2019). Social disorganization theory: Past, present and future. In M. D. Krohn, N. Hendrix, A. J. Lizotte, & G. P. Hall (Eds.), Handbook on Crime and Deviance (pp. 197-211). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-20779-3_11

Kubrin, C. E. & Tublitz, R. (2023). Social disorganization theory and community-based interventions. In E. Verona & B. Fox (Eds.), Routledge handbook of evidence-based criminal justice practices. Taylor & Francis Group.

Kubrin, C. E., & Weitzer, R. (2003). New directions in social disorganization theory. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, 40(4), 374-402. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022427803256238.

Morenoff, J.D., Sampson, R.J., & Raudenbush, S. (2001). neighborhood inequality, collective efficacy, and the spatial dynamics of urban violence. Criminology, 39, 517-560.

Park, R. & Burgess, E. (1925/1967). The city: Suggestions for investigation of human behavior in the urban environment. University of Chicago Press.

Pauwels, L. J. R., Bruinsma, G. J. N., Weerman, F. M., Hardyns, W., & Bernasco, W. (2018). Research on neighborhoods in European cities. In G. J. N. Bruinsma & S. D. Johnson (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of environmental criminology. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190279707.013.9

Pratt, T. C., & Cullen, F. T. (2005). Assessing macro-level predictors and theories of crime: A meta-analysis. Crime and Justice, 32, 373-450.

Quetelet, A. (1842). A treatise on Man. Chambers.

Renauer, B. C., Cunningham, W. S., Feyerherm, B., O’Connor, T., & Bellatty, P. (2006). Tipping the scales of justice: The effect of overincarceration on neighborhood violence. Criminal Justice Policy Review, 17(3), 362-379.

Rose, D.R. & Clear, T.R. (1998). Incarceration, social capital, and crime: Implications for social disorganization theory. Criminology, 36, 441-480. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-9125.1998.tb01255.x

Sampson, R.J. (1987). Urban black violence: The effect of male joblessness and family disruption. American Journal of Sociology, 93, 348-82.

Sampson, R.J. (2009). Collective efficacy theory: Lessons learned and directions for future inquiry. In F.T. Cullen, J.P. Wright, & K.R. Blevins (Eds.), Taking Stock: The Status of Criminological Theory (pp. 149-167). Taylor & Francis Group. http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/griffith/detail.action?docID=4906154

Sampson, R.J. (2011). The community. In J. Q. Wilson & J. Petersilia (Eds.), Crime and public policy. Oxford University Press.

Sampson, R.J. (2012). Great American City: Chicago and the enduring neighborhood effect. University of Chicago Press.

Sampson, R. J., & Groves, W. B. (1989). Community structure and crime: Testing social-disorganization theory. American Journal of Sociology, 94(4), 774-802.

Sampson, R.J., Morenoff, J.D. & Gannon-Rowley, T. (2002). Assessing ‘neighborhood effects’: Social

processes and new directions in research. Annual Review of Sociology, 28, 443-478.

Sampson, R. J., Raudenbush, S. W., & Earls, F. (1997). Neighborhoods and violent crime: A multilevel study of collective efficacy. Science, 277(5328), 918–924. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2892902

Shaw, C. R. & McKay, H.D. (1931). Report on the causes of crime: Social factors in juvenile delinquency, National Commission on Law Observance and Enforcement (Vol. 2, Tech. Rep. No. 13). U.S. Government Printing Office.

Shaw, C. R. & McKay, H.D. (1942/1969). Juvenile delinquency and urban areas. University of Chicago Press.

Snodgrass, J. (1976). Clifford R. Shaw and Henry D. McKay: Chicago criminologists. The British Journal of Criminology, 16(1), 1–19.

Staines, Z., & Scott, J. (2020). Crime and colonisation in Australia’s Torres Strait Islands. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Criminology, 53(1), 25-43. https://doi.org/10.1177/0004865819869049

Sydney’s population. (1920, March 3). The Sydney Morning Herald (NSW : 1842 – 1954), p. 11. Retrieved December 2, 2023, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article28094787.

Thomas, W. I. & Znaniecki, F. (1927). The Polish peasant in Europe and America. Alfred A. Knopf.

University of Chicago. (1934). Census tracts of Chicago grouped into 148 areas showing population density per sq. mile, 1920. University of Chicago Press.

Vieraitis, L. M., Kovandzic, T. V., & Marvell, T. B. (2007). The criminogenic effects of imprisonment: Evidence from state panel data, 1974–2002. Criminology & Public Policy, 6(3), 589-622.

Western, B. (2007). Mass imprisonment and economic inequality. Social Research: An International Quarterly, 74(2), 509-532.

Wickes, R. & Sydes, M. (2017). Social disorganization theory. obo in Sociology. https://doi.org/10.1093/obo/9780199756384-0192.

Williams, K. S. (2012). Textbook on criminology. Oxford University Press.

Wilson, W. J. (1987). The truly disadvantaged. University of Chicago Press.

Wirth, L. (1938). Urbanism as a way of life. American Journal of Sociology, 44, 3-24.

- This series was based on the book The Corner: A Year in the Life of an Inner-City Neighborhood byDavid Simon and Edward Burns. ↵

- For more information on the life and career of Professor Robert Bursick, check out this interview with him and Professor Brendan Dooley as part of the Oral History Criminology Project of the American Society of Criminology. ↵

- This image shows the relationship between social disorganisation, weak social controls, and crime. When there are high levels of social disorganisation, neighbourhoods can have weak social ties, which may result in low collective efficacy, which can lead to crime. ↵

- Learn more about Professor Todd Clear from this interview with Professor Natasha Frost as part of the Oral History Criminology Project of the American Society of Criminology. ↵

- While some researchers have suggested police calls for service might serve this purpose, these are predicated on the willingness of residents to engage with police. ↵