11 Crime and Delinquency over the Life Course: Developmental Theories of Crime

Stacy Tzoumakis

Learning Objectives

- To gain an overview of Developmental and Life-Course Criminology theories.

- To understand the importance of age and different developmental periods in DLC theories.

- To become familiar with risk and protective factors, and turning points in the life-course.

Before You Begin

- Think back to your own adolescence. Do you act the same way now? Why or why not? What do you think has changed the most in your life?

- Why do so many young people become involved in some form of antisocial behaviour or offending (e.g., shoplifting, drink driving, physical fighting) during adolescence?

- Why do some young people stop after a year or two, and why do some continue into adulthood?

INTRODUCTION

In the previous chapters, you have read about several different theoretical perspectives on criminal behaviour and many ways to understand why people make the decisions that they do. One thing that these theories of criminal behaviour have in common is that they are all generally static in nature. This means that these theories use one point in a person’s life to predict future behaviour. But there is an argument to be made that suggests that people’s behaviour, including the things that predict a person’s behaviour, can be different over time. And true to their name, Developmental and Life Course (DLC) criminological theories offer explanations that incorporate human development. In this chapter, you will learn about several DLC theories.

The first important point to understand about Developmental and Life-course (DLC) criminology theories is that this framework is not a single theory. DLC theories consist of a set of theories that are sometimes referred to as a perspective. DLC theories can be considered multifactor theories, which means that they include several different factors that can explain criminal behaviour. This can be contrasted with theories that focus on single factors such as social learning or social control. Some DLC theories take a more developmental approach, looking at factors early in life, others a life-course approach, looking at events later in life, and some integrate both. While DLC theories share many key concepts, notably the importance of age and timing of life events, they are not all the same and can have important differences (McGee & Farrington, 2019). This chapter will provide information about the historical context, a description of key concepts, applications, criticisms, as well as some thoughts on the future of DLC theories.

HISTORICAL CONTEXT

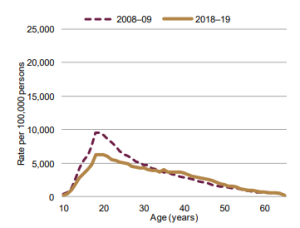

The relationship between age and crime is well established in criminology[1]. In short, it involves a sharp increase in the prevalence of antisocial/criminal behaviour in mid to late adolescence followed by a rapid decrease in early adulthood that continues to slowly decline over time. This relationship between age and crime has been observed as early as the 19th century in Belgium by Quételet, one of the founders of sociology (Quételet, 1831). In a seminal paper, Hirschi and Gottfredson (1983) proposed that the age distribution of crime is essentially invariant; meaning that the shape of the distribution of the age-crime relationship stays the same regardless of the type of data (official or self-report data), historical period, gender, race, or culture. You may remember Gottfredson and Hirschi from Chapter 9. To demonstrate this, see Figure 12.1 for the age-crime curves for Queensland in the 2000’s and 2010’s (Queensland Government Statistician’s Office, 2023).

While there is little disagreement about the existence of the robust relationship between age and crime, there has been much debate, research, and theorising to explain it. Up until about the 1990s, most theories that emerged in the field of criminology sought to explain this pattern. Given the clear empirical evidence that the bulk of offending over the life-course occurs in the period of adolescence/young adulthood, this meant that up to this point in history most criminological theories, and in particular classic single factor theories such as social learning (Chapter 10) and social control theories (Chapter 8), were essentially focused on the explanation of adolescent offending. Cullen (2011) suggested that for half a century criminology was dominated by research and theory that is adolescent-focused and sociological in orientation. He stated that this adolescence focused criminology neglected childhood and adulthood and that criminologists need consider the life course to move forward.

DLC criminology theories were the first to emphasise the importance of developmental periods in life beyond adolescence and to consider the whole of a person’s life, also known as their life course. They also underlined the importance of having longitudinal data (repeated measures of the same individuals over time) rather than cross-sectional data (i.e., a snapshot of one time point) limited to adolescence. In 1986, Professor Alfred Blumstein[2] and colleagues authored Criminal Careers and Career Criminals, a foundational volume that examined longitudinal patterns of offending over the life course. Some of the key criminal career concepts that form the basis of DLC theories today came from this volume, including but not limited to: onset (i.e., when people start offending); escalation (i.e., an increase in offending behaviour); persistence (i.e., the continuation or maintenance of offending behaviour); and desistance (i.e., the slowing down and eventual cessation of offending). Where these concepts describe patterns of offending over the life-course, the DLC theories that emerged afterward sought to explain them. The next section describes some key DLC concepts and important DLC theories in further detail.

KEY DLC CONCEPTS

DLC theories seek to explain the relationship between age and crime as well as the patterning of offending over different developmental periods. According to DLC theories, there are underlying developmental processes associated with different patterns of offending (Le Blanc & Loeber, 1998; Loeber & Le Blanc, 1990). This can be comparted to earlier theories of offending that have mostly focused on explaining offending primarily in the period of adolescence. For example, one of the processes that policymakers have become increasingly concerned with is desistance. Most people who have engaged in antisocial/criminal behaviour do not simply stop offending one day. Rather, they experience a complex process that unfolds over time. This process leads to a slowing down of the frequency of offending and a reduction of the seriousness of offending. Therefore, from both a theoretical and policy perspective, it is extremely useful to understand what causes this specific process so that it is possible to help individuals’ journeys out of crime.

Taking a developmental life-course perspective to understand social or behavioural phenomena is not specific to criminology; researchers in psychology, psychiatry, public health, and sociology are also increasingly taking a developmental life-course approach. The core of this involves understanding how people develop and change over different life stages. However, there are importance differences between developmental and life-course approaches in DLC criminology theories. The two can be quite different in terms of what they identify as the key underlying reasons for antisocial behaviour and offending. Developmental approaches generally come from the field of psychology and tend to focus on individual and psychological factors in early developmental periods, while life-course approaches tend to come from sociology and focus more on social structure and later developmental periods (Kazemian et al., 2018). In broad terms, developmental approaches are more interested in the onset of offending, while life-course approaches are more interested in desistance from offending. Many DLC theories have integrated both approaches, and both are needed to fully understand all the processes involved in antisocial behaviour and offending.

DLC criminology theories are considered multidisciplinary because they are influenced by other disciplines like those mentioned above, but also because they are not solely interested in criminal offending behaviour. DLC theories recognise the importance of other related behaviours or socially disruptive behaviours beyond delinquency and offending such as risky sexual behaviour, underage drinking, drug use and gambling (Morizot & Kazemian, 2014). DLC theories examine different forms of antisocial behaviour over different developmental periods over the life course. For example, a difficult temperament in infancy can lead to aggressive behaviour in early childhood, followed by physical fighting in adolescence, which can turn into assault in young adulthood. A key aim of DLC theories is to understand the development and unfolding of antisocial behaviour and offending over different stages of life.

To explain antisocial behaviour and offending, DLC criminology theories emphasise the role of risk and protective factors. Risk factors are defined as something that increases the chances of later antisocial behaviour or offending. There are many different types of risk factors including individual, family, peer, school and community factors (for a review Jolliffe et al., 2017). Examples of some of the most consistent risk factors for offending that have been identified in criminological research include poor parental supervision, low empathy, parental offending, low school motivation and peer delinquency (Farrington et al., 2017; Jolliffe et al., 2017). However, it is critical to note that risk factors are not necessarily causal; just because an individual experiences one or more risk factors, does not mean that they are destined to become involved in offending. It only means that the chances of an individual offending are greater than someone without those risk factors. Several DLC theories also suggest that the influence of risk factors is cumulative; this means that the more risk factors an individual has, the more they will have in subsequent developmental periods, in turn increasing the likelihood an individual will become involved in offending.

Understanding how certain risk and protective factors influence maternal maltreatment assists in developing intervention and prevention strategies to minimise further harm. The aim of the study is to improve our understanding of mothers who maltreat and how their risk and protective factors differ to those mothers who do not maltreat. The current study identified limitations in the methodologies of previous research, with many using cross-sectional data with small sample sizes and a lack of a comparison group. Given the long-term consequences of childhood maltreatment, the researchers used the developmental and life criminology (LDC) framework as a guide and adopted a prospective design which included a comparison group using longitudinal data from a large sample size to overcome limitations within the current literature.

To perform a population-based comparative analysis, data was collected from the Queensland Cross-sector Research Collaboration (QCRC) as well as records from Births, Deaths, and Marriages. The study focused on mothers born in Queensland during 1983 and 1984 who were aged between 30 and 31 years old and had contact with the child protection services and criminal justice system to compare with individuals who had not been recorded as having maltreated their children. The total sample compared 18,019 mothers with 998 of those as categorised as maltreating.

This study addressed two research questions, the first being are there significant differences between mothers who maltreat and who don’t based on five factors: Indigenous status, the age when they had their first child, the number of births, whether they were ever married, and whether they were maltreated as a child. The second question is does the combination of these variables differentiate between mothers who maltreat and those who don’t.

Five findings from the study found significant correlations between risk factors and maltreatment. First, there was a significant relationship between maternal age and maltreatment, with young mothers aged 19 or younger at the birth of their first child more likely to maltreat their child. Second, mothers who were more likely to maltreat had more than three children. Third, mothers who had a history of maltreatment victimisation were significantly more likely to maltreat than those with no history, with childhood victimisation being the most significant risk factor. Fourth, those who were never married are more likely to maltreat than those who are married, and finally, Indigenous mothers were found three times more likely to maltreat their children than non-Indigenous mothers.

The study identified limitations including using administrative data which limits the range of risk factors. The researchers suggest that future research should include additional risk factors as well as examine the timing of a range of risk and protective factors to determine the impacts on transitions and turning points over the life course as part of the LDC framework.

The implications for policy and practice highlight the need to target certain cohorts of the population who are more likely to face risk factors and include them in home-visitation programs, education on contraception, and culturally appropriate strategies and action plans for Indigenous families.

A summary by Melissa Osborn

Protective factors are generally defined as something that decreases the chances of later antisocial behaviour or offending. However, there are different definitions of protective factors; some researchers describe them as factors that prevent risk factors from increasing the likelihood of offending (see Farrington et al., 2016). For example, coming from a family with a high income and having high intelligence are examples of protective factors because they can act to decrease the likelihood of other risk factors such as joining delinquent peer groups. There are also promotive factors, which are slightly different to protective factors. Promotive factors are defined as something that predicts low chances of offending or predicts desistance from offending (Loeber et al., 2007). Examples of promotive factors includes low peer delinquency or having a small peer group, which can decrease the chance individuals become involved in antisocial behaviour or delinquency. Although DLC theories may not always agree about what increases (or decreases) someone’s chances of becoming involved in antisocial behaviour or offending, they all incorporate the role of risk and protective factors.

DLC theories are not focused on simply identifying risk and protective factors for antisocial behaviour and delinquency, but they also emphasise the timing of these factors. These theories aim to determine which factors are important at specific developmental periods. This has important implications for prevention and intervention. For example, it is well established that harsh and punitive parenting is a risk factor for delinquency, especially in early to middle childhood. However, as children get older, the family slowly becomes less of an influence on behaviour compared to peers. In adolescence, peer delinquency becomes an important risk factor for delinquency, even more so than parenting practices. Therefore, accounting for the timing of risk and protective factors helps to develop more appropriate and effective programs that target the right things at the right times.

There are many different DLC theories (for reviews, see Farrington, 2005; Kazemian et al., 2018). The next section details two influential DLC theories that are often contrasted to one another: Moffitt’s developmental taxonomy (Moffitt, 1993), which can be considered a developmental approach; and Sampson and Laub’s age graded theory of social control, which can be considered a life-course approach (Sampson & Laub, 1993, 2017).

Developmental taxonomy

Professor Terrie Moffitt’s[3] (1993) developmental taxonomy is one of the most influential theories that adopts a developmental approach. She proposed the Dual Taxonomy (i.e., two taxonomic groups or types) of: 1) life-course persistent, and 2) adolescent limited antisocial behaviour. These two groups refer to two distinct categories of individuals that have different histories and underlying reasons for becoming involved in antisocial behaviour. These two groups are what explain the relationship between age and crime as discussed earlier (Figures 12.1).

The life-course persistent antisocial group represents a small and segment of the population. These individuals start getting involved in antisocial behaviour early and continue throughout adolescence and into adulthood. They tend to get involved in more serious and frequent antisocial behaviour. They have behavioural problems that start in childhood before school entry. According to the theory, life-course persistent antisocial individuals have early neuropsychological (i.e., temperament, behavioural development, and cognitive abilities) deficits that lead to problems with social interactions. These individuals experience numerous environmental risk factors for antisocial behaviour that interact with each other and accumulate over the life course (e.g., poor parent-child interactions, delinquent peers, problems in school, etc.). Extensive research has examined Moffitt’s theory and there is generally strong evidence for the existence of the life-course persistent group (for reviews see Eme, 2020; Moffitt, 2017).

The Dunedin Multidisciplinary Health and Development Study

The adolescent-limited antisocial group represents a much larger segment of the population compared to the life-course persistent group. Unlike the life-course persistent group, these individuals do not have a history of behavioural problems in childhood. When the adolescent limited antisocial group reaches adulthood, for the most part, they stop offending and engaging in antisocial behaviour. Individuals in the adolescent limited antisocial group become involved in offending during adolescence because of what Moffitt terms the ‘maturity gap’ that happens when they hit puberty and want to obtain social maturity (e.g., have adult roles and finances) but are unable to. They see their life-course persistent counterparts and mimic them by getting involved in antisocial behaviour.

In general, Moffitt’s development taxonomy tends to emphasise the importance of infancy and early childhood factors to explain the development of antisocial behaviour. The developmental taxonomy places less emphasis on adulthood compared to other DLC theories. The next section provides an overview of a theory that emphasises adulthood rather than childhood and adolescence.

Age graded theory of social control

Professors Robert Sampson and John Laub’s[4] age graded theory of social control (Laub & Sampson, 2003; Sampson & Laub, 1993) is an influential DLC theory that adopts a life-course approach. Their theory tends to focus more on adulthood rather than childhood. It builds on social control theory (Chapter 8) and places a lot of importance on the role of informal social control (e.g., pressure from family, school, community to follow norms) to explain persistent offending and desistance from crime. Specifically, weak adult attachments to things like family, work and community are central to this theory.

According to the age graded theory of social control, when a person’s bond to society is weakened, they are more likely to become involved in crime (Laub et al., 2018). A central part of their theory is the idea of turning points; these are described as a change in the life course that can modify a life trajectory or redirect a person’s path (Sampson & Laub, 1993). Key turning points examined in the theory include marriage, parenthood, military service, and work/career. For example, for some people, moving to a new city to start a new job can provide them an opportunity to leave their past behind, change their paths (or trajectories), have more positive and structured routines, and lead to desistance from crime. Similarly, individuals who get married and/or have children create stronger attachments to their family unit and may be more motivated to behave in pro-social ways in order to continue to have strong family relationships.

Research evaluating the evidence for turning points is complex and methodologically challenging. Because of this, some of the findings for the theory has been mixed, particularly for employment. Overall, however, there has been support for the effect of a ‘good marriage’ on helping with desistance (for a review Laub et al., 2018). Because desistance is a complex (and often gradual) process, it is difficult to evaluate specific turning points. Human agency and a person’s motivation or choice to make a conscious effort to get out of a life of crime are also important parts of desistance. Nonetheless, there is extensive qualitative research suggesting that turning points do play a part in desistance from offending (Laub & Sampson, 2003; Veysey et al., 2013).

APPLICATION OF DLC THEORIES

DLC theories have been embedded across numerous prevention and intervention programs and strategies to prevent and reduce crime. Developmental crime prevention is an emerging area of prevention research that is based on the idea that we should provide evidence-based[5] resources for individuals, families, schools and communities to prevent or minimise the impact of risk factors for crime (Homel, 2021; Homel & Thomsen, 2017; Welsh & Tremblay, 2021). Having information about which risk and protective factors are most important at specific stages in life are critical for developing interventions and preventions that work to prevent and reduce crime. For example, according to Moffitt’s developmental taxonomy, life-course persistent antisocial individuals can be identified as early as infancy and early childhood. Therefore, parenting programs and support services targeting pregnant mothers who have a lot of risk factors could help to stop their children from getting on a life-course persistent antisocial trajectory.

One example of this is home visitation programs such as the Nurse-Family Partnership (Olds, 2006). This is a program for low-income, first-time mothers who are paired up a with a nurse in pregnancy. The nurse conducts home visits until the child’s second birthday to help and support with parenting (see the link at the end of the chapter for a video example from the U.S.). There is strong longitudinal evidence that this program reduces multiple negative outcomes for their children, including antisocial behaviour and offending (Olds, 2006). The Nurse-Family Partnership program has been adapted for Australian women pregnant with an Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander and there is research showing that it improves child protection outcomes (Segal et al., 2018) and improves mother’s self-efficacy (Massi et al., 2023).

DLC THEORIES IN AUSTRALIA

There are many Australian criminologists whose work is guided by DLC theories as well as several ongoing longitudinal studies in Australia that are following people over the life course (for a review Mazerolle & McGee, 2017). For example, the Pathways to Prevention Project takes a developmental prevention approach to providing interventions in a disadvantaged community in Queensland (Homel et al., 2006). The Pathways to Prevention project targets children aged 4 to 6 years old and works with families, preschools and schools to provide programs to support these children to successfully transition to school (Homel et al., 2006). Other Australian DLC research includes Smallbone and Cale (2015), who proposed a life‐course developmental theory of sexual offending. There are also several Australian studies guided by DLC approaches that use repeated measures of administrative data (i.e., data collected in the daily operations of an organisation such as police, courts, corrections) to examine large samples of individuals over time in New South Wales (Payne & Piquero, 2020; Tzoumakis et al., 2020) and Queensland (Stewart et al., 2015).

Several studies have described offending trajectories of young people who have committed sex offences (e.g., Cale et al., 2016). Offending trajectories are longitudinal offending patterns over time and are helpful to identify factors and outcomes associated with different courses of offending (Loeber & Le Blanc, 1990). One way to investigate various factors and outcomes associated with different courses of offending is to be able to identify youth characterised by different offending trajectories and conduct an in-depth qualitative investigation of their developmental backgrounds and the characteristics of their sexual offending behaviour. This was the aim of the research.

A purposive sample of 12 archived case files from 2002-2009 were utilised for the study. Cases were chosen based on the total number of charges (i.e., those with the most extensive histories of charges) recorded in their criminal history and whether they had been convicted of a sexual offence and subsequently referred to the Griffith Youth Forensic Service (GYFS) for treatment. This was also stratified based on ethnicity and geographical location.

A qualitative collective case study analysis (Yin, 2003) was utilised in order to explore similarities and differences in and between cases to better understand this complex phenomenon. This allowed for the identification of unique developmental pathways and sexual offending contexts among young people referred to GYFS.

Braun and Clarke’s (2006) thematic analysis was used to identify and interpret emerging themes within the data. Themes were organised in consideration of the three domains in line with the developmental criminology theoretical approach (i.e., socio-cultural, individual/social cognitive and situational).

Analysis of the case files showed both commonalities and differences across young people’s ecological systems, individual factors and situational aspects of the young person’s sexually abusive behaviour. More specifically, some commonalities included experiences of household dysfunction, parental separation, abandonment and rejection, as well as intimate partner violence and adverse childhood experiences.

Key points of divergence included familial structures, social learning mechanisms and offence characteristics. More specifically, there were differences across these young people in terms of their immediate family make-up, how topics of sexuality and sexual development were learned and modelled, and differences in offence characteristics such as the young person’s relationship to a victim, and the presence of co-offenders in sexually abusive incidents.

The findings demonstrated that while all of the young people had extensive contacts with the criminal justice system and had been charged with a sexual offence, even among this group of young people there were unique aspects of their developmental histories that contributed in different ways to the commission of a variety of sexually abusive behaviours.

This research provided some insight into different developmental pathways of youth who commit harmful sexual behaviours that have had extensive contacts with the justice system. In short, there is no single developmental pathway leading to sexual offences, even among youth with extensive criminal justice system contact. This has important implications for tailoring treatment to fit the individual risk different youth pose and their needs across different developmental domains. Furthermore, this research specifically focused on one type of offending trajectory and future studies should explore these domains among youth with different longitudinal offending patterns.

In the field of sexual violence research, it is now recognised more than ever that young people who commit sexual offences are characterised by much heterogeneity across virtually all developmental domains. Furthermore, the nature of sexual offending behaviour committed by these young people varies quite dramatically (e.g., in terms of severity, level of planning, motivation etc.). In effect, the notion that there is a single ‘profile’ that characterises these young people is increasingly becoming one of the past (Worling, 2013).

CRITICISMS OF DLC THEORIES

One of the main criticisms of DLC theories is the that much of the evidence base is from samples of white urban males that are no longer contemporary. For example, much DLC research is based on samples of men who were born in the 1920-1930’s (Laub & Sampson, 2003) or the 1950s (Farrington et al., 2016). While this work has been instrumental in developing important DLC criminology theories, there is a need for new samples that are more representative of today’s diverse society. Although many of the seminal cohort studies were exclusively male, there are several studies that included girls and some DLC theories that are specific to females (Caspi et al., 2001; Keenan et al., 2010; Lanctôt & Le Blanc, 2002; Putallaz & Bierman, 2004). Despite this, there remains a need for more contemporary cohorts to update and replicate parts of DLC theories. As society changes and new technologies emerge, DLC and other theories need to account for the social and economic contexts of younger generations (e.g., impact of the covid pandemic and cost of living crisis; the rise of social media) and new forms of crime (e.g., cybercrime).

THE FUTURE OF DLC THEORIES

A new volume on the future of DLC research was recently published and it highlights new opportunities, techniques and methodologies for understanding changes in antisocial behaviour and offending over time, with an emphasis on how to achieve better outcomes for individuals and communities (Malvaso et al., 2024). One of the difficulties with conducting DLC research is the need for detailed longitudinal data. Collecting longitudinal data that covers key developmental periods from infancy to adulthood is time consuming, costly, and logistically difficult to collect. For instance, following up over many years to interview at-risk people who move frequently and do not necessarily want to be found is challenging. Traditional longitudinal cohort surveys have been a valuable source of data for DLC theories, but there are some concerns about their ongoing feasibility due to high costs, attrition (individuals dropping out over time), and relatively low response rates (Laub & Sampson, 2020). Linked administrative data[6] can be used as a complement to traditional longitudinal surveys and address some of these limitations. For example, as detailed in Thompson et al. (2024), large cohorts of people can be identified and followed over time that include information on contacts with multiple government departments (e.g., justice, health, education, child protection, and employment, etc.). Since the data already exist and is held by government departments, record linkage studies have fewer costs, can be less time consuming, and minimise attrition and recall bias (Thompson et al., 2024). Combining cross-sectional surveys with administrative record linkage (Green et al., 2018; Rivenbark et al., 2018) is one of the ways to move DLC research forward in contemporary cohorts.

CONCLUSION

This chapter provided an introductory overview of DLC criminology theories. DLC theories are a complex and diverse group of theories that aim to explain the development of antisocial behaviour and offending over the life course. The importance of timing and age are key parts of DLC theories. While the theories do not always share the same underlying explanations for offending, they are all concerned with understanding processes such as onset, persistence, and desistance. DLC research and theories need to be updated to reflect contemporary society. The use of administrative linked data is one way to obtain these up-to-date cohorts and move the field forward.

Check Your Knowledge

DISCUSSION QUESTIONS

- What do we know about the relationship between age and crime?

- What are risk factors? Are they causal?

- What are some of the differences between developmental and life-course approaches?

REFERENCES

Blumstein, A., Cohen, J., Roth, J., & Visher, C. (1986). Criminal careers and career criminals (Vol. National Academy Press Washington, DC.

Caspi, A., Rutter, M., Silva, P. A., & Moffitt, T. E. (2001). Sex differences in antisocial behaviour : conduct disorder, delinquency, and violence in the Dunedin longitudinal study. Cambridge University Press.

Cullen, F. T. (2011). Beyond adolescence‐limited criminology: Choosing our future—the American Society of Criminology 2010 Sutherland address. Criminology, 49(2), 287-330.

Eme, R. (2020). Life course persistent antisocial behavior silver anniversary. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 50, 101344.

Farrington, D. P. (2005). Integrated developmental and life-course theories of offending: Advances in Criminological Theory (Vol. 14). Routledge.

Farrington, D. P., Gaffney, H., & Ttofi, M. M. (2017). Systematic reviews of explanatory risk factors for violence, offending, and delinquency. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 33, 24-36.

Farrington, D. P., Ttofi, M. M., & Piquero, A. R. (2016). Risk, promotive, and protective factors in youth offending: Results from the Cambridge study in delinquent development. Journal of Criminal Justice, 45, 63-70. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrimjus.2016.02.014

Green, M. J., Harris, F., Laurens, K. R., Kariuki, M., Tzoumakis, S., Dean, K., Islam, F., Rossen, L., Whitten, T., & Smith, M. (2018). Cohort profile: the New South Wales child development study (NSW-CDS)—wave 2 (child age 13 years). International Journal of Epidemiology, 47(5), 1396-1397k.

Hirschi, T., & Gottfredson, M. (1983). Age and the explanation of crime. American journal of sociology, 89(3), 552-584.

Homel, R. (2021). Developmental Crime Prevention in the Twenty-first Century: Generating Better Evidence Embedded in Large-scale Delivery Systems. Journal of Developmental and Life-Course Criminology, 7(1), 112-125.

Homel, R., Freiberg, K., Lamb, C., Leech, M., Carr, A., Hampshire, A., Hay, I., Elias, G., Manning, M., & Teague, R. (2006). The pathways to prevention project: The first five years, 1999–2004. Griffith University and Mission Australia, Sydney.

Homel, R., & Thomsen, L. (2017). Developmental crime prevention. In N. Tilley & A. Sidebottom (Eds.), Handbook of crime prevention and community safety (pp. 57-86). Taylor & Francis.

Jolliffe, D., Farrington, D. P., Piquero, A. R., Loeber, R., & Hill, K. G. (2017). Systematic review of early risk factors for life-course-persistent, adolescence-limited, and late-onset offenders in prospective longitudinal studies. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 33, 15-23.

Kazemian, L., Farrington, D. P., & Piquero, A. R. (2018). Developmental and life-course criminology. In D. P. Farrington, L. Kazemian, & A. R. Piquero (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of developmental and life-course criminology (pp. 3-10). Oxford Handbooks.

Keenan, K., Hipwell, A., Chung, T., Stepp, S., Stouthamer-Loeber, M., Loeber, R., & McTigue, K. (2010). The Pittsburgh Girls Study: overview and initial findings. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 39(4), 506-521.

Lanctôt, N., & Le Blanc, M. (2002). Explaining deviance by adolescent females. Crime and justice, 29, 113-202.

Laub, J. H., Rowan, Z. R., & Sampson, R. J. (2018). The age-graded theory of informal social control. In D. P. Farrington, L. Kazemian, & A. R. Piquero (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of developmental and life-course criminology (pp. 295-322). Oxford Handbooks.

Laub, J. H., & Sampson, R. J. (2003). Shared beginnings, divergent lives: Delinquent boys to age 70. Harvard University Press.

Laub, J. H., & Sampson, R. J. (2020). Life-course and developmental criminology: Looking back, moving forward—ASC Division of Developmental and Life-Course criminology Inaugural David P. Farrington Lecture, 2017. Journal of Developmental and Life-Course Criminology, 6, 158-171.

Le Blanc, M., & Loeber, R. (1998). Developmental criminology updated. Crime and justice, 23, 115-198.

Loeber, R., & Le Blanc, M. (1990). Toward a developmental criminology. Crime and justice, 12, 375-473.

Loeber, R., Pardini, D. A., Stouthamer-Loeber, M., & Raine, A. (2007). Do cognitive, physiological, and psychosocial risk and promotive factors predict desistance from delinquency in males? Development and psychopathology, 19(3), 867-887.

Malvaso, C., Mcgee, T. R., & Homel, R. (2024). Frontiers in developmental and life-course criminology: Methodological innovation and social benefit. Taylor & Francis.

Massi, L., Hickey, S., Maidment, S.-J., Roe, Y., Kildea, S., & Kruske, S. (2023). “This has changed me to be a better mum”: A qualitative study exploring how the Australian Nurse-Family Partnership Program contributes to the development of First Nations women’s self-efficacy. Women and Birth.

Mazerolle, P., & McGee, T. R. (2017). Developmental and life-course criminology. The Palgrave Handbook of Australian and New Zealand Criminology, Crime and Justice, 557-570.

McGee, T. R., & Farrington, D. P. (2019). Developmental and life-course explanations of offending. Psychology, Crime & Law, 25(6), 609-625. https://doi.org/10.1080/1068316X.2018.1560446

Moffitt, T. E. (1993). Life-course-persistent and adolescence-limited antisocial behavior: A developmental taxonomy. Psychological review, 100(4), 674-701.

Moffitt, T. E. (2017). A review of research on the taxonomy of life-course persistent versus adolescence-limited antisocial behavior. Taking stock, 277-311.

Morizot, J., & Kazemian, L. (2014). The development of criminal and antisocial behavior. Springer.

Olds, D. L. (2006). The nurse–family partnership: An evidence‐based preventive intervention. Infant Mental Health Journal, 27(1), 5-25.

Payne, J. L., & Piquero, A. R. (2020). Developmental criminology and the crime decline: a comparative analysis of the criminal careers of two New South Wales Birth cohorts. Cambridge University Press.

Putallaz, M., & Bierman, K. L. (2004). Aggression, antisocial behavior, and violence among girls : a developmental perspective. Guilford Press.

Queensland Government Statistician’s Office. (2023). The age distribution of crime by offence type in Queensland: Crime research report. Queensland Treasury.

Quételet, A. (1831). Research on the propensity for crime at different ages. Crime: Critical concepts in sociology, 119-135.

Rivenbark, J. G., Odgers, C. L., Caspi, A., Harrington, H., Hogan, S., Houts, R. M., Poulton, R., & Moffitt, T. E. (2018). The high societal costs of childhood conduct problems: evidence from administrative records up to age 38 in a longitudinal birth cohort. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 59(6), 703-710.

Sampson, R. J., & Laub, J. H. (1993). Crime in the making: Pathways and turning points through life. Crime & Delinquency, 39(3), 396-396.

Sampson, R. J., & Laub, J. H. (2017). A general age-graded theory of crime: Lessons learned and the future of life-course criminology. In Integrated developmental and life-course theories of offending (pp. 165-182). Routledge.

Segal, L., Nguyen, H., Gent, D., Hampton, C., & Boffa, J. (2018). Child protection outcomes of the Australian Nurse Family Partnership Program for Aboriginal infants and their mothers in Central Australia. PLoS One, 13(12), e0208764.

Smallbone, S., & Cale, J. (2015). An integrated life‐course developmental theory of sexual offending. Sex offenders: A criminal career approach, 43-69.

Stewart, A., Dennison, S., Allard, T., Thompson, C., Broidy, L., & Chrzanowski, A. (2015). Administrative data linkage as a tool for developmental and life-course criminology: The Queensland Linkage Project. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Criminology, 48(3), 409-428.

Thompson, C., Hurren, E., McCarthy, M., Ogilvie, J., Allard, T., Tzoumakis, S., & Dennison, S. (2024). Linked administrative data: Providing unique solutions to key challenges in developmental and life-course criminology. In C. Malvaso, T. R. Mcgee, & R. Homel (Eds.), Frontiers in developmental and life-course criminology (pp. 9-19). Routledge.

Tzoumakis, S., Whitten, T., Piotrowska, P., Dean, K., Laurens, K. R., Harris, F., Carr, V. J., & Green, M. J. (2020). Gender and the intergenerational transmission of antisocial behavior. Journal of Criminal Justice, 67, 101670.

Veysey, B. M., Martinez, D. J., & Christian, J. (2013). “Getting Out:” A summary of qualitative research on desistance across the life course. In C. L. Gibson & M. D. Krohn (Eds.), Handbook of life-course criminology: Emerging trends and directions for future research (pp. 233-260). Springer New York. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-5113-6_14

Welsh, B. C., & Tremblay, R. E. (2021). Early developmental crime prevention forged through knowledge translation: A window into a century of prevention experiments. Journal of Developmental and Life-Course Criminology, 7, 1-16.

- Refer back to Chapter 3 for some information about how age is a very strong correlate with crime. ↵

- For more information about Professor Blumstein, check out this interview with Professor Blumstein and Professor Robert Sampson from the Oral History Project of the American Society of Criminology. ↵

- [3] Professor Terrie Moffitt talks to Professor Brendan Dooley in this interview for the Oral History Project from the American Society of Criminology. ↵

- Professor John Laub talks to Professor Brendan Dooley in this interview for the Oral History Project of the American Society of Criminology. ↵

- For more information about evidence based crime prevention, check out this resource from the New South Wales Government. ↵

- Administrative data are data that comes from official government sources but it not limited to crime data. For example, administrative data can include information from a variety of social service and welfare agencies, like Centrelink, and also include data from government agencies on health or education. When these data are used in research, they are treated very carefully and there are very high levels of safety for individuals involved, including ensuring that a person’s name is not released. Researchers who work with these data are very careful and have to follow many rules in order to respect individual privacy. ↵