12 You Made Me Do It: Social Reaction Theory

Tracy Meehan and Antoinette L. Smith

Learning Objectives

- Understand the fundamental principles of social reaction theories and be able to explain labelling and reintegrative shaming perspectives.

- Explore how the process of assigning deviant labels influences individual identity formation, societal reactions, and the perpetuation of deviant behaviour.

- Assess reintegrative shaming theory as a complementary perspective to social reaction theory, assessing its potential for fostering positive social reintegration, reducing recidivism, and promoting community cohesion in contrast to stigmatising forms of social control.

Before You Begin

- Have you ever judged a person after one interaction with them? Was the judgement positive or negative? What factors influenced your perception?

- Have you ever behaved in an atypical way in front of someone that you did not know very well? What was the outcome. Were you your best self? How did you feel after that interaction? How do you think the person would describe you after seeing you behave that way?

- How do you forgive someone after they have hurt you? Are there some things that you can forgive easier than others - or some people that you can forgive easier than others? Why do you think that is the case?

INTRODUCTION

In many of the previous explanations of criminal behaviour, we have focused on explaining the behaviour of an individual person. Now we turn our attention to the reactions to those behaviours from people around us. Originating mainly from criminology, social reaction theory diverges from conventional theories that attribute crime primarily to the inherent traits of individuals (see Chapter 9 for more information about the General Theory of Crime) or their social surroundings (see Chapter 6 for more information about Social Disorganisation Theory). Instead, it asserts that society's responses to deviant behaviour significantly shape individuals' identities, actions, and paths within the legal system. At its core, social reaction theories question the presumption that deviance is an objective, inherent trait of specific individuals. Instead, it proposes that what consists of deviant behaviour is socially constructed and varies across different contexts and historic periods. If you stop and think about the changes in what is considered socially acceptable in your own lifetime, you will probably come up with several examples. The editors, for example, remember a time when tattoos were considered socially taboo and having a tattoo would indicate criminal associations, something that seems rather silly in 2024.

According to these theoretical perspectives, individuals become branded as deviant or criminal through their interactions with societal entities, such as the criminal justice system or other members of society. This happens through a process of labelling, described below, and attaches negative, or stigmatising, descriptions to people who engage in socially unacceptable behaviours. Once labelled, individuals may internalise these identities, leading to self-fulfilling prophecies and more participation in deviant behaviour. Additionally, the imposition of societal labels can result in social exclusion, marginalisation, and limited opportunities to re-engage with mainstream society. Social reaction theory also underscores the influence of power dynamics in the labelling process. Certain groups, such as racial minorities or individuals from lower socioeconomic backgrounds, may face disproportionate targeting for labelling and stigmatisation by societal entities. This uneven distribution of labelling reinforces existing inequalities and perpetuates cycles of deviance and marginalisation.

Moreover, social reaction theories critique traditional methods of social control, such as punitive measures employed by the criminal justice system, for accelerating deviant behaviour through stigmatisation and marginalisation. Social reaction theories advocate for restorative justice approaches that prioritise mending harm caused by deviant acts and reintegrating offenders into the community. Overall, social reaction theory offers a valuable framework for understanding the social dynamics underlying deviant behaviour and the ramifications of societal reactions to deviance.

HISTORICAL CONTEXT

Social reaction theory (sometimes referred to as ‘labeling theory’) emerged in the mid-20th century as a response to the dominant perspectives in criminology that focused primarily on individual traits or societal factors as the primary drivers of crime. Instead, social reaction theories argue that the way society reacts to individuals who engage in deviant behaviour can significantly influence future actions and identities. The roots of social reaction theory can be traced back to the works of scholars such as Emile Durkheim and George Herbert Mead. Durkheim's concept of anomie (see Chapter 5: Sociological Theories of Crime) highlighted the breakdown of social norms as a cause of deviant behaviour, while Mead's symbolic interactionism emphasised the importance of social interactions and labelling in shaping individual identity. Social reaction and labelling theories gained momentum with the emergence of the Chicago School of Sociology (see Chapters 6 and 7). Researchers like Edwin Sutherland and Howard Becker[1] conducted studies on how social processes, particularly labelling of others, contribute to the development of criminal behaviour. Becker's work "Outsiders: Studies in the Sociology of Deviance" (1963) explored how the application of labels such as "criminal" or "deviant" can lead individuals to adopt those identities. These early explanations of labelling theory emphasised that societal reaction to deviance is a key mechanism in perpetuating criminal behaviour.

While social reaction theory offered valuable insights into the dynamics of deviance and social control, critics have been concerned about its simplicity. Some scholars argue that it overlooks the structural factors that may contribute to deviant behaviour, such as poverty and inequality (Becker, 1963; Young, 1999). Others criticise its deterministic view of the labelling process, suggesting that not all individuals who are labelled will internalise deviant identities. Subsequent developments in the theory, such as the distinction between primary and secondary deviance discussed below, attempt to address these criticisms. Social reaction theory continues to be influential in criminology and sociology. It has been applied to various contexts, including studies on juvenile delinquency, drug use, and the criminal justice system (Gove et al., 1979; Chambliss, 1988). Recent advancements in research explores the intersections of labelling processes with other social phenomena, such as race, gender and social media experiences.

SOCIAL REACTION THEORIES

Labelling Theory

Labelling theory is a sociological viewpoint centred on a societal process of assigning labels and categories to individuals or groups, and the subsequent impact of these labels on their actions and self-perception. This theory emerged in the mid-20th century as a response to traditional criminological theories that primarily focused on the individual's innate characteristics or social structure as the primary determinants of deviant behaviour.

Primary and Secondary Deviance

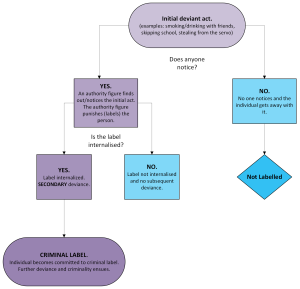

Primary deviance relates to the initial acts of rule-breaking behaviour, something that most people engage in at some point in time, and is often not part of a person's self-concept or identity. These initial acts may go unnoticed, or if noticed, often have minimal consequences. However, when an individual is labelled as deviant, they may internalise this label and engage in secondary deviance, which involves more serious or frequent rule-breaking behaviour as a reaction to their societal label (Goode, 1996).

Individuals engage in primary deviance for various reasons, such as experimentation, peer pressure, or situational factors. Importantly, primary deviance alone does not typically result in long-term consequences or a lasting societal label (Venkatesh, 2006; Gibbs, 2016). Secondary deviance occurs when an individual's primary deviant behaviour is labelled by others, leading to the person adopting the deviant label as part of their identity. Once labelled, individuals may begin to see themselves and be seen by others through the lens of the deviant label. This can result in a self-fulfilling prophecy, whereby an individual will internalise the label and further engage in deviant behaviour as a response to societal reactions and expectations (Lemert, 1951; Gibbs, 2016). Figure 1 explains how this happens.

While social labels largely serve as ways for individuals to define and categorise the ways in which society works, deviant labels possess a unique quality of being stigmatising. Deviant labels, particularly those associated with criminality, carry a stigma, whereby mainstream culture attaches negative connotations or stereotypes to them (Link & Phelan, 2001). These negative stereotypes are widespread in our society and are often reinforced through mainstream culture in such forms as mass media, books and even everyday language (Becker, 1963; Goffman, 1963; Scheff, 1974).

Individuals identified as criminals are often segregated and linked to stereotypes depicting unwanted traits (Link, 2001). Becker (1963) proposed that this deviant designation could become the primary identity for an individual, overshadowing other attributes they possess. Being labelled a criminal implies several associated characteristics that are presumed to apply to anyone with that label. The labelled individual is perceived as incapable of behaving morally and thus may be expected to violate other important norms. Furthermore, any past or future transgressions may be interpreted as evidence of their inherent criminal nature (Becker, 1963). Research suggests that the stigma associated with being labelled as a criminal fosters widespread distrust and contempt towards anyone who is unfortunate enough to be on the receiving end of such a description (Bernburg, 2009).

Table 13.1 Social Reaction Theory – Timeline

| 1930-1940s | The roots of labelling theory can be traced back to the works of sociologists associated with the Chicago School, such as Edwin Sutherland and Howard Becker. They emphasized the importance of social context in understanding deviant behaviour. |

| 1960 | Howard Becker publishes "Outsiders: Studies in the Sociology of Deviance," which is considered a foundational text in labelling theory. Becker argues that deviance is not inherent in certain behaviours but is rather a result of societal reactions to those behaviours. |

| 1963 | Erving Goffman publishes "Stigma: Notes on the Management of Spoiled Identity," introducing the concept of stigma and examining how individuals manage their identities in response to societal labels. |

| 1966 | Edwin Lemert publishes "Social Pathology," where he distinguishes between "primary" and "secondary" deviance. Primary deviance refers to initial rule-breaking behaviour, while secondary deviance occurs when individuals internalize societal labels and adopt a deviant identity. |

| 1972 | Thomas Scheff publishes "Being Mentally Ill," applying labelling theory to the context of mental illness and arguing that societal reactions to mental illness can exacerbate individuals' symptoms. |

| 1980s | Labelling theory continues to be influential in criminology and sociology, with scholars exploring its application to various contexts, including juvenile delinquency, drug use, and the criminal justice system. |

| 1989 | Labelling theorist John Braithwaite publishes "Crime, Shame, and Reintegration," proposing a theory of reintegrative shaming, which suggests that certain forms of societal reaction to deviance can lead to the reintegration of offenders into society. |

| 1990-2000s | Restorative justice movements gained popularity around this time, reiterating the idea that offenders maybe positively integrated back into communities using elements of reintegrative shaming. These included helping offenders to make amends for their actions. This led to the development of new and improved criminal justice system responses which focused on more holistic approaches to preventing crime and rehabilitating offenders. |

| 2000-present | Labelling theory remains relevant in contemporary criminology and sociology, with researchers continuing to refine and expand upon its concepts and applications. There is ongoing debate and discussion surrounding the limitations and critiques of labelling theory, as well as its implications for policy and practice in areas such as criminal justice reform and mental health treatment. |

Reintegrative Shaming

One major advancement on social reaction theories is that of reintegrative shaming, unique in criminology for its integration of culturally diverse philosophies. Reintegrative shaming is a complex and popular theory drawing from several philosophies, including integration, deterrence, labelling, social control, strain, and subcultural theories (Botchkovar & Tittle, 2008; Tosouni & Ireland, 2008) and also firmly rooted in Indigenous knowledges and methodologies. Articulated by Australian National University Professor John Braithwaite[2] (1995), this theory examines the role of shame in affecting human behaviour. Braithwaite argues that shaming can be an effective social control measure and can encourage individuals to comply with social norms, so long as public shame is combined with a process of acknowledgement, apology, and forgiveness, which can then be used to reintegrate an offending individual back into society. Reintegrative shaming is the process of extending behavioural disapproval through respectful relationships between communities and offenders. Braithwaite pointed out that lower crime rates in certain communities may mean that these societies were effectively communicating that engaging in criminal behaviour would cause shame (Braithwaite et al., 2018). For instance, if tagging is publicised as being a shameful behaviour, it will occur less often than in societies who do not consider graffiti shameful. Therefore, this process of shaming can create an environment where individuals will avoid these behaviours in order to avoid feeling shaming.

But shame can also cause the opposite effect, similar to a process of labelling. This results in stigmatisation, especially if shame is inconsistently or disproportionately applied (Ajunwa, 2015). A very famous international example of this comes from the United States and its War Against Drugs. The American Anti-Drug Abuse Act 1986 was a form of legislation that was passed in reaction to the crack epidemic that happened in many major American cities in the 1980s. Among other thigs, this legislation introduced punishments for different types of drugs, including two different types of cocaine: crack cocaine and powdered cocaine. Crack cocaine users, who were typically of Black or African American descent, were punished more significantly by the criminal justice system, whereas users of cocaine powder, more commonly used by affluent and white communities, were treated much less severely. The rationale became known as the 100:1, with one gram of crack cocaine receiving the same punishment as 100 grams of cocaine powder. This resulted in the disproportionate shaming and stigmatisation of African American people and communities, while more affluent criminals avoided the same harsh levels of shame due to their lesser punishments (Braithwaite et al., 2018).

The theory of reintegrative shaming has three main implications within criminology: shaming, stigmatisation, and reintegration (Braithwaite et al., 2018). Shaming a person means disrespecting and labelling them as being permanently bad and unworthy of reintegration into society, leading to offenders’ feeling humiliated. Stigmatisation is the permanent labelling of people as criminal, which can occur when someone is disrespected during degradation ceremonies (such as criminal justice processes) and faces permanent isolation from society (Braithwaite, 1995; Forsyth & Braithwaite, 2020). Conversely, instead of stigmatising, some processes of shaming can lead to reintegration. A process called reintegrative shaming prevents future crimes by allowing starting from the perspective that individuals who offend should be treated with dignity and respect and these individuals are not bad people, they have merely committed bad actions. As such, they are capable of repentance and thus worthy of reintegration (Braithwaite et al., 2017). Shame for these otherwise deserving people is often short lived and ends in ceremonies of forgiveness or apology (Braithwaite, 1995). An example of these ceremonies can be seen in ‘youth justice conferencing’, where young people accept the consequences of their actions, meet with their victims, and come to a mutual agreement about compensation for the harms caused (Hayes & Daly, 2003). We often call this process restorative justice and it is widely practiced in Australia. In this way, reintegrative shaming theory and youth justice conferences both require the offender to feel shame for their actions while still providing pathways for individuals to be welcomed back into communities. Research suggests that when crime is effectively shamed in communities and reintegration practiced, crime rates are lower (Braithwaite, 1995).

Restorative justice is heavily tied to the notion that people have strong attachment to families, social networks, and community systems around them (Braithwaite, 1989). People with strong feelings of attachment would harm their reputation and lose access to these social networks if they engage in these shameful activities (Botchkovar & Tittle, 2008). However, shaming is thought to have less of an impact for people who do not share close bonds with their families and communities, which is why guilt is thought to be an equally important part of reintegrative shaming. Braithwaite and colleagues consider shame and guilt to work in unison, where people who think of, or engage in, shamed activities, feel subsequent guilt and that is why they will choose to desist (Ahmed et al., 2001).

One caveat of reintegrative shaming is that this process can only work if offenders internalise shame and have strong attachment ties to the community. When communities are well integrated with social and familial networks, such as is very common in many Asian countries, shaming may be more effective in reducing crime than in cultures with weak community ties (Botchkovar & Tittle, 2008). To better understand how this works, researchers are investigating why some cultures have stronger ties than others and focusing on ways to strengthen bonds in communities with weaker cultural ties (Forsyth & Braithwaite, 2020).

THEORY APPLICATIONS

Rehabilitation and reintegration

The central tenants of this theory have intuitive links to improved offender rehabilitation and reintegration in the criminal justice system. For instance, Kim and Gerber (2010) found the level of supporters from loved ones is positively associated with with effective reintegration in young offending populations. Similarly, Murphy and Harris (2007) identified that white collar criminals who were encouraged to reintegrate into their communities were less likely to reoffend than those who were not connected with their communities. In a very unique study, Murphy and Harris were able to survey over 600 Australian tax offenders who were caught and punished for investing in illegal tax avoidance schemes. Individuals were asked about their experiences with the Australian Tax Office and whether or not they felt that the experience was stigmatising or reintegrative. Those offernders who felt that the experience with the ATO was reintegrative were less likely to report further tax evasion after two years. This points to the importance of both understanding the role that shame plays in behaviour but also understanding how institutions can create - or mitigate - shame in individuals (Murphy & Harris, 2007).

Restorative justice programs

The popularity of restorative justice programs, such as youth, family and diversionary conferencing, continues to grow in Australia (Queensland Government, 2024). Drawing on the principles of reintegrative shaming theory, these processes involve reducing stigmatisation and encouraging reintegration of offenders to reduce recidivism. Studies continue to show success for improved criminal justice system responses and reductions in offending rates. The most well know study conducted by Sherman et al. (1998) explored outcomes for drunk drivers and juvenile offenders who participated in diversionary conferences underpinned by reintegrative shaming practices. These researchers found that offenders felt they were treated more fairly, they felt less stigmatised and were less likely to reoffend than offenders in control groups. Similarly, Harris (2006), analysed the experiences of 720 Australians charged with driving while over the legal alcohol limit. Results showed that offenders who were involved in restorative justice programs felt more integrated within their communities than those who did not participate. These kinds of promising results are the reasons that restortative justice programs continue to be popular intervention tactics used by the court system.

CRITICISMS

Social reaction theories have faced several criticisms. First, critics argue that social reaction theories can be deterministic in its portrayal of individuals as passive recipients of societal labels. The premise that the labelling process means that individuals will continue to engage in deviance ignores individual agency and decision making and also suggests that individuals cannot change. Social reaction theories are also criticised for their neglect of broader structural factors such as poverty, inequality, and systemic discrimination. Critics argue that this narrow focus fails to address the root causes of deviance and crime embedded within societal structures.

Offenders must also be the ones to internalise shame, which is not always the case. Braithwaite (1995) himself acknowledged this issue when discussing a then growing problem of young Australian males abusing their mothers. He believed in these circumstances, it was the mothers who felt shame for being abused, rather than the young males themselves. Other researchers have found a similar displacement of shame with survivors of intimate partner abuse feeling shame and guilt for being victims (Beck et al., 2011). This indicates that where offenders are unwilling or unable to internalise guilt, reintegrative shaming is less likely to be an effective prevention strategy.

Finally, critics have argued that the impacts of shame may be highly destructive for offenders’ mental health (Botchkovar & Tittle, 2008). In cases where offenders internalise the stigmatisation of shame, they may feel anger or inferiority rather than shame, and therefore counter shameful attitudes with a level of moral superiority. These researchers argue that the process of reintegrating offenders back into communities may not be enough to remove their feelings of shame; if feelings of shame are not removed, criminal behaviour could continue to increase (as is hypothesised by the transition from primary to secondary deviance). These criticisms point to the importance of understanding how these processes differ between individuals and between communities and offer ways to re-imagine the labelling and shaming process in different cultural contexts.

By primarily focusing on formal labels applied by institutions such as the criminal justice system, these theories can also underestimate the significance of informal labels and social reactions from peers, family, and community.

THE FUTURE OF THE SOCIAL REACTION THEORIES

Future research in social reaction theory should incorporate intersectionality, which considers how various social identities (such as race, gender, class, and sexuality) intersect and interact to shape individuals' experiences of labelling and deviance. Social reaction theories have primarily emerged from research conducted in Western contexts, with the exception of some studies on reintegrative shaming. There is much to learn by incorporating learnings from non-Western societies and considering how cultural, historical, and institutional factors influence labelling processes and responses to deviance. Understanding how multiple social identities intersect across cultures can provide us with deeper insights into the complexities of deviant behaviour and societal reactions (Forsyth & Braithwaite, 2020).

Continued research in social reaction theory will also inform policy and practice in criminal justice, education, healthcare, and other domains. Understanding the consequences of labelling and stigmatisation for non-criminal behaviours, for example, can help the public health sector better support healthy behavioural change around things like drug and alcohol use or poor eating habits. Criminal behaviour is not the only kind of deviant behaviour and social reaction theories have already been used to help understand willingness to seek treatment for mental illness (Markowitz, 2017; Ray & Dollar, 2017) and obesity (Liu et al., 2019; Mustillo et al., 2013). This will lead to the development of more effective and equitable interventions and policies aimed at reducing social inequalities and supporting individuals affected by deviance labels. Future research will utilise longitudinal research designs to track individuals over time and examine the long-term effects of labelling and social reactions on individuals' life trajectories, including outcomes related to mental health, employment, education, and social relationships.

Overall, the future direction of social reaction theory is likely to be interdisciplinary, incorporating insights from sociology, psychology, criminology, communication studies, public health and other fields to deepen our understanding of labelling processes and their consequences for individuals and societies.

CONCLUSION

Social reaction theories offer valuable insights into the complexities of deviance and societal responses to it. Through this theory, we have explored the dynamics of labelling and the consequences of societal reactions on individuals and communities. The notion that deviance is not inherent but rather socially constructed underscores the importance of understanding the role of power, social control mechanisms, and cultural norms in shaping perceptions of deviant behaviour. You will have the opportunity to explore these concepts in more depth in Chapter 14. Moreover, the introduction of reintegrative shaming theory highlights the potential for transformative approaches to addressing deviance, emphasising the importance of restoring social bonds and promoting rehabilitation over punitive measures. As we continue to deal with issues of crime, deviance, and social justice, social reaction theory serves as a crucial framework for critically analysing the interplay between social structures, reactions, and the construction of deviant identities.

Check Your Knowledge

Discussion Questions

- Social reaction theory emphasises the importance of considering the social context in understanding crime. How might factors such as race, class, and gender influence the labelling process and subsequent societal reactions to deviance?

- Social reaction theory suggests that the criminal justice system can exacerbate deviant behaviour through labelling and stigmatisation. Do you agree with this assessment? Why or why not?

- Consider the implications of social reaction theory for crime prevention and intervention strategies. How might understanding the social reactions to deviance inform efforts to reduce crime and promote social inclusion?

REFERENCES

Ahmed, E., Harris, N., Braithwaite, J., Braithwaite, V., 2001. Shame Management Through Reintegration. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Ajunwa, I. (2015). The modern day scarlet letter. Fordham Law Review, 83(101).

Beck, J. G., McNiff, J., Clapp, J. D., Olsen, S. A., Avery, M. L., & Hagewood, J. H. (2011). Exploring negative emotion in women experiencing intimate partner violence: Shame, guilt, and PTSD. Behavior therapy, 42(4), 740-750.

Becker, H. S. (1963). Outsiders: Studies in the sociology of deviance. Free Press Glencoe.

Botchkovar, E., & Tittle, C. R. (2008). Delineating the scope of Reintegrative Shaming theory: An explanation of contingencies using Russian data. Social Science Research, 37(3), 703-720.

Braithwaite, J., 1989. Crime, Shame, and Reintegration. Cambridge University Press, New York.

Braithwaite, J. (1995). Diversion, reintegrative shaming and republican criminology. Diversion and informal social control, 141-157.

Braithwaite, J., Ahmed, E., & Braithwaite, V. (2017). Shame, restorative justice, and crime. In Taking Stock (pp. 397-417). Routledge.

Braithwaite, J., Braithwaite, V., & Ahmed, E. (2018). Reintegrative Shaming 1. In The Essential Criminology Reader (pp. 286-296). Routledge.

Chambliss, W. J. (1988). Exploring criminology (Ser. Macmillan criminal justice series). Macmillan.

Farrington, D. P., & Murray, J. (Eds.). (2017). Labeling theory: Empirical tests. Routledge.

Forsyth, M., & Braithwaite, V. (2020). From reintegrative shaming to restorative institutional hybridity. International Journal of Restorative Justice, 3 (10).

Gibbs, J. C. (2016). Deviance and deviants: A sociological approach (New York Academy of Sciences series). John Wiley & Sons, Incorporated.

Goffman, E. (1963). Stigma. Notes on the Management of Spoiled Identity. London: Penguin Books.

Goode, E. (1996). Social deviance. Allyn and Bacon.

Gove, W., Cullen, F. J., & Cullen, J. B. (1979). Toward a paradigm of labeling theory. Contemporary Sociology, 8(2), 245–245. https://doi.org/10.2307/2066140

Harris, N. (2006). Reintegrative Shaming, Shame, and Criminal Justice. Journal of Social Issues, 62(2), 327-346.

Hayes, H., & Daly, K. (2003). Youth justice conferencing and reoffending. Justice Quarterly, 20(4), 725-764.

Jetten, J., & Hornsey, M. J. (2011). Rebels in groups : dissent, deviance, difference and defiance. Wiley-Blackwell.

Kim, H. J., & Gerber, J. (2010). Evaluating the process of a restorative justice conference: An examination of factors that lead to reintegrative shaming. Asia Pacific Journal of Police & Criminal Justice, 8(2), 1-20.

Kim, H. J., & Gerber, J. (2017). Shaming, reintegration, and restorative justice: Braithwaite in Australia, New Zealand, and around the globe. The Handbook of the History and Philosophy of Criminology, 289-305.

Lemert, E. M. (1951). Primary and secondary deviation. In E. Rubington, & M. S. Weinberg (Eds.), The study of social problems: Seven perspectives (pp. 192-195). New York: Oxford University Press.

Lemert, E. M. (1951). Social pathology; A systematic approach to the theory of sociopathic behavior. McGraw-Hill.

Lemert, E. M. (1967). Human deviance, social problems, and social control. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Link, B. G., & Phelan, J. C. (2001). Conceptualizing stigma. Annual Review of Sociology, 27, 363–385.

Liu, J., Lee, B., McLeod, D. M., & Choung, H. (2019). Framing obesity: Effects of obesity labeling and prevalence statistics on public perceptions. Health Education & Behavior, 46(2), 322-328.

Markowitz, F. E. (2017). Labeling theory and mental illness. In D. Farrington (Ed.), Labeling theory (pp. 45-62). Routledge.

Murphy, K. & Harris, N. (2007). Shaming, shame and recidivism: A test of reintegrative shaming theory in the white-collar crime context. The British Journal of Criminology, 47(6), 900–917.

Mustillo, S. A., Budd, K., & Hendrix, K. (2013). Obesity, labeling, and psychological distress in late-childhood and adolescent black and white girls: The distal effects of stigma. Social Psychology Quarterly, 76(3), 268-289.

O’Connell, M. & Hayes, H. (2015). Victims, Criminal Justice and Restorative Justice. In H. Hayes & T. Prenzler (Ed.). An Introduction to Crime and Criminology (4th ed., pp. 222-339). Pearson.

Queensland Government (2024). Restorative Justice Conference Program Evaluation.

Ray, B., & Dollar, C. B. (2014). Exploring stigmatization and stigma management in mental health court: Assessing modified labeling theory in a new context. Sociological Forum, 29(3), 720-735.

Scheff, T. J. (1974). The labelling theory of mental illness. American Sociological Review, 39(3), 444–452.

Sherman, L. W., Strang, H., Barnes, G. C., Braithwaite, J., Inkpen, N., & Teh, M. M. (1998). Experiments in Restorative Policing: A Progress Report.

Tosouni, A & Ireland, C. (2008). Shaming youthful offenders: An empirical test of Reintegrative Shaming Theory. International Journal of Restorative Justice, 14(2), 101-126.

Venkatesh S.A. (2006) Off the books: the underground economy of the urban poor. Harvard University Press.

Young, J. (1999). The Exclusive Society: Social Exclusion, Crime and Difference in Late Modernity. SAGE

- For more information about Professor Howard Becker and his work, check out this interview between Professor Becker and Professor Brendan Dooley of the Oral History of Criminology Project from the American Society of Criminology. ↵

- For more information about the work of Professor John Braithwaite, check out this interview with Professor Jay Albanese, recorded for the Oral History of Criminology Project from the American Society of Criminology. ↵