People in Health and Social Care

Talent Management, Recruitment and Selection

Richard Olley

Introduction

Despite the pressures of the current economy, three things remain high priorities for workforce management in the health sector. First, organisations must maintain a diverse workforce reflective of the increasingly diverse society in which we live. This requirement is essential to building the capability to meet future challenges, because we require innovation in thinking and service delivery that such diversity brings. Failure to address this could lead to the loss of valuable talent. Equity and equality are also essential within the health and social care workforce. Not only because to do otherwise would counter the laws of most developed and democratic countries, but also for the diversity reasons already discussed. Finally, talent management assists with understanding the organisation’s skills, experience, and capabilities requirements to enable delivery on the mission and strategic objectives set. Leading talent management strategies in the workforce is a critical function of health and social care leaders, including the vital functions of recruiting, selecting, and retaining the workforce, performance management of staff through implementing equitable and legal disciplinary procedures, and the importance of the training and development of the workforce.

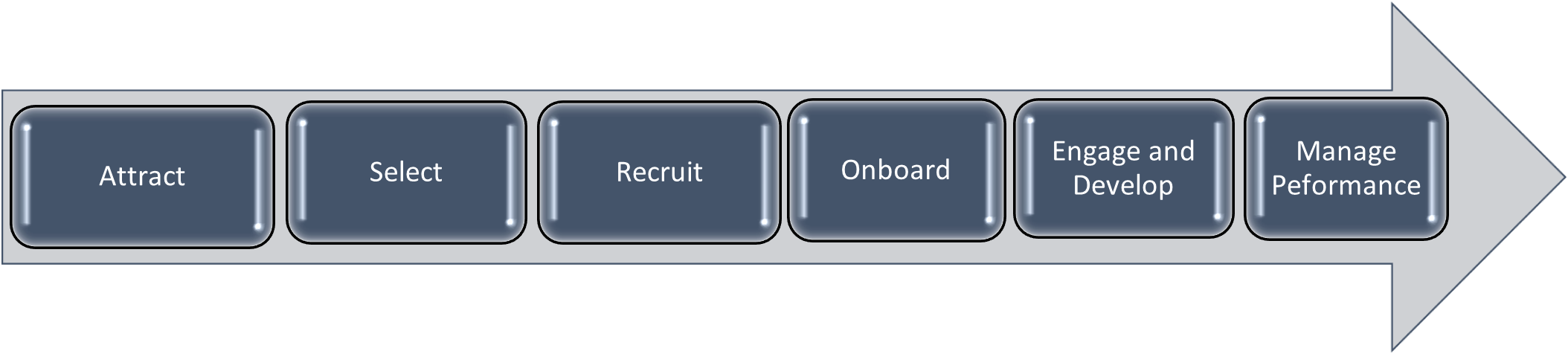

Overall, talent management may be considered a series of six connected and interdependent processes that are, in some cases, systems. The figure below details these processes that make up that system.

This chapter examines attracting, recruiting, and retaining talent in the health and social care workforce and the important function of tracking the performance of an organisation’s talent management system using talent management metrics.

Attracting, Recruiting and Retaining Talent

Attracting the right person to the right job at the right time is the goal of any organisation embarking on recruitment processes. Retaining the right person for the job is enormously important. This task is made even more complex due to the competition between healthcare and social care providers experienced globally, particularly in recent times (van den Broek et al., 2018). The costs of recruitment and selection procedures and onboarding and orientation of new staff are climbing (Castro Lopes et al., 2017), so they must be carefully managed, particularly in the fiscally tight environment of the health and social care sectors.

The benefits of talent management are well-documented in the literature (Naulleau, 2019, Papa et al., 2018). Leaders who concentrate their efforts on implementing a talent management strategy that empowers staff to perform at their best will drive success in the recruitment of talent that is in demand ahead of their competitors for staff. They will minimise service disruption by establishing a talent pipeline, and therefore maintain service operations by filling any vacancies quickly (Mitosis, Lamnisos, and Talias, 2021). Additionally, they will improve the productivity of their workforce, reduce costs, and encourage innovation by and within their workforce (Wadhwa and Tripathi, 2018).

Attracting Candidates

Attracting talent is the first and the most important function of talent management, because if an organisation cannot attract candidates, there is no one to move into the selection process. Talent attraction refers to the organisation’s ability to persuade potential staff to apply to join the organisation. There are several opportunities to consider when deciding what strategies to use for a successful outcome. There is a critical shortage of workers in the health and social care sector (Klimek et al., 2020, Dussault and Zurn, 2020, Van den Heede et al., 2020), and this has a great impact on the sustainability of services because health and social care is a labour-intensive enterprise.

The critical skills shortage experienced globally has made health and social care an increasingly competitive market (Ybema, van Vuuren, and van Dam, K, 2020). Related to the de-funding of Health Workforce Australia in 2015, limited Australian data is available, other than scanning the job vacancies in organisational job boards and other media advertising for staff. One survey conducted in the United States by Glassdoor (2023) , an employer branding and staff sourcing company, found that health and social care organisations had the longest average time to employ in any industry, with 23% of positions needing about 112 days to fill, lengthy by any standard. There is no data to confirm whether this is the case in Australia, but anecdotally, it appears to take a long time to employ.

Attracting high-performing candidates is achieved by harnessing the outputs from channels such as:

- Organisational job boards that prospective candidates use to search for positions that interest them.

- Online healthcare job sites, similar to organisational job boards.

- Social media channels such as LinkedIn.

- Referrals from existing and former staff.

- Professional association web sites, because they foster networking by some of the best talents for the various disciplines and professional groups in health and social care and often conduct conferences and continual professional development opportunities and events aimed at career advancement for their members.

- The organisation employing internal talent management specialists to scan various other channels and put a personal touch on recruiting staff.

- External health and social care recruiters, who can be freelance recruiters or those who work within a large recruitment specialist firm.

This list is by no means exhaustive or specific for either healthcare or social care because there is wide choice. The important point is to find channels and organisations that are successful for the particular discipline or professional group organisations are searching. The literature suggests that the use of publicly available channels relates to the organisation’s brand and is the intersection of marketing and talent management (Yohn, 2020). Helping to attract the best talent is especially important in labour markets like health and social care, which have intense competition for the scarce health and social care workforce. Health and social care organisations that are prominent and unique in some way must offer potential candidates persuasive reasons to apply for workforce vacancies (Yohn, 2020).

The health and social care organisation’s reputation and brand, and the marketing of that brand are important. A German study by Hoppe (2018) sampled 366 hospital healthcare professionals and found increased organisational attractiveness, organisational identification, and favourable employee behaviours to corporate branding lead to increased retention.

The Recruiting and Selection Processes

Sourcing Candidates

Selection of the right candidate who best matches the organisational culture sets the baseline for employee behaviour, employee interaction with healthcare consumers and families, and employee-to-employee relationships. Without a culture match, organisations set themselves up for long-term retention issues (Nangoli et al., 2020), with workforce metrics demonstrating climbing attrition and turnover rates. Without retention of employees who match the organisational culture, results will not improve, and may worsen in terms of quality, safety, and costs. The organisation’s brand will suffer as a consequence. Recruitment and selection are the centrepieces of any talent management system. Its success or failure will be felt throughout the organisation to change or maintain the organisational culture, consumer experience, staff experience, and viability.

Tracking Applicants

Tracking applicants and their applications, including their resumes, is the next step in recruitment and selection. Applicant tracking can be a manual process, and for some organisations, applicant tracking systems (ATS) are rapidly becoming extremely helpful to those seeking to attract new talent. This technology aids in the management of authorised recruitment when a vacancy is identified and applications are received for every open position. Employment specialists use an applicant tracking system to review applications.

Abilities, Aptitude, and Skills Tests

These tests can be either pencil and paper tests or job sample tests. They assess the abilities, aptitudes, or skills required for the job. Both types of tests are scored, with minimum scores established to screen applicants. The “cut-off” score can be raised or lowered depending on the number of applicants and the quality of applications received. When selection ratios are low, the cut-off score can be raised, increasing the odds of employing better qualified employees.

Only after thorough and careful job analysis should tests be selected. For example, an examination of a job description for a central sterile supply technician would show that manipulation of parts and pieces relative to one another and the ability to perceive geometric relationships between physical objects are required. These abilities are a part of a construct called mechanical aptitude. For care-related positions, the focus would be more related to soft skills of communication, respect for all people, caring aptitudes, some ability to multi-task, and technical skills related to the type of care the person is expected to deliver. Some organisations develop their job sample tests rather than relying on commercially available aptitude tests. Job simulation exercises are closely related to job sample tests as part of the selection process, placing applicants in simulated job situations to observe what they do.

Personality Tests

Certain jobs require unique personalities or temperaments. We sometimes occupy specific jobs due to personal work preferences. However, there is little evidence that people must have a specific personality type to succeed at a particular job. In describing the use of personality tests for determining suitability for a rural nursing appointment, Terry and colleagues attempted to consider whether personality trait assessment assists in understanding professional career choices (Terry et al., 2019). They found that the two general personality tests are self-report and projective personality tests, sometimes deployed to decide which applicant best fits the job demands. These tests are also frequently used as part of assessment centres, a popular method of identifying potential talent.

Personality measures may adversely impact the process (Risavy and Hausdorf, 2011). Other critics contend that it is difficult to demonstrate that personality characteristics are job relevant (Santos et al., 2018). Job specifications should emphasise the skills and abilities needed for a job rather than personality traits. Personality measures assess specific personality constructs rather than behavioural patterns associated with the job. Scepura (2020) asserted that health and social care leaders involved in approving recruitment and selection processes should consider eliminating the use of instruments that screen for personality traits. According to Scepura (2020), this relates to the risks associated with candidate profiling, favouring processes that identify candidates with diverse credentials. These diverse credentials in candidates signal to consumers and other staff that the organisation honours diversity and inclusion, and will therefore better serve the increasing number of culturally diverse consumers and staff by eliminating trait profiling in the selection process.

The Selection Panel

What needs to be clearly understood when forming an interview panel is that interviewing is not an innate skill. Training is required for the merit process to operate as intended relating to panel members and panel chairs. Without appropriate training, there is an increased risk of inequities in the selection process, and therefore increased risk of reputational damage and lawsuits.

In the interests of credibility, the chairperson, or delegated officer, should have a defensible rationale for committee members’ inclusion (or exclusion). It is important to have a gender balance, selection panel diversity, appropriate professional credentials, and a process for disclosing any conflicts of interest when assembling the selection panel. As a rule, those appointed to the panel should be experts in the field and have the confidence of all panel members.

Selection Panel Responsibilities

The chairperson of the selection panel ensures the fairness of the selection process and has the responsibility of reminding all members of their duties, which include:

- ensuring the confidentiality of the proceedings,

- the requirement to declare a conflict of interest,

- anti-discrimination and privacy legislation requirements, and

- organisational policies on recruitment and selection and equal opportunity.

Merit Processes

The author defines a merit system as employing and promoting employees that emphasise their ability, education, experience, and job performance, rather than their connections or other factors. The merit process is governed by uniform and impersonal policies and procedures. Merit processes should be followed throughout the selection process, from advertisement to the selection panel’s recommendations. It is important to understand that merit applies throughout the employment process, not just in the selection interview.

Observing merit principles is most obvious during the interview process, and the selection panel uses these in their deliberations for the important task of selecting successful candidates based on their ability, knowledge, and skills to perform the role for which they have applied.

Shortlisting of Applicants for Interview

Interview short listing may include a preliminary phone interview before the applicant is invited to a panel interview. An initial review of an applicant’s submitted documents will reveal those applicants who do not meet the minimum requirements for the job. While a talent specialist may probe further into an applicant’s experience and people skills, this interview aims to narrow the applicant field for consideration. Conducting a preliminary phone interview will obtain information about an applicant’s background, work history, and experience. The objective is to determine whether or not the applicant has the requisite skills and qualifications for the job. From this point, the applicant field is narrowed to a “shortlist” of candidates considered of equal merit before the formal interview or other selection processes.

Selection Interviews

Well prior to inviting any applicant to a more formal interview/selection process, organisational policy will dictate what method or methods will be used in the selection process. Several selection methods available for the selection processes used in the recruitment. Because interviews are the most common form of selection process, it is discussed here in some detail.

Selection interviews are tools that allow the exchange of information between applicants and interviewers relating to an applicant’s suitability for the job. Interviewers can then probe more intensely in the interview to elicit additional relevant information.

Watch this video “How to Interview Candidates for a Job”

Video Source: Videojug. 2011. How to Interview Candidates for a Job. Available at https://youtu.be/d6uzZqkcsa8

Common interview panel mistakes include:

- Lack of preparation, either in job requirements or applicant history and interests.

- Being nervous about the responsibilities of panel members or the panel’s work.

- Being overly blasé or indifferent and failing to connect with the applicant.

- Being overly enthusiastic and not allowing the applicant to complete responses to the questions asked.

- Intimidating the candidate through the interview style portrayed.

- Not being able to fully answer legitimate questions the interviewee asks about the position or the organisation.

- Apparent bias or a conflict of interest exhibited by panel member.

- Being overly friendly or oversharing with the applicant.

- Being unfair in questioning or not properly listening to the applicant’s answers.

- Being overly kind, to the point of making the applicant uncomfortable.

Reflection

Read the list of selection panel mistakes listed above.

Think about interview panels you have experienced as an applicant or as part of a selection panel.

Identify which (if any) of the list you have experienced, as either an interviewee or interviewer.

List others not mentioned above.

Reflect on how you felt about the identified mistakes and what you would do next time to prevent them from happening again.

Approval following Selection Committee Report

The selection report is effectively the minutes of the implemented selection process. The report’s main purpose is to convey the panel’s recommendation and provide enough information for the delegate with authority to authorise the candidate’s employment to make an informed and fair recruitment decision. In most organisations, there is a requirement for the “one-up” rule to apply. This means that the person who can approve a candidate’s employment is at least one level in the hierarchy above the person’s immediate supervisor or manager. This is a check and balance so that merit processes are evident and the talent management processes are followed.

Of-course, there are methods in addition to those already discussed. Group assessment centres set various tasks and hurdles for the applicants to complete under observation and group activities to demonstrate applicants’ soft and technical skills. The deployment of these methods is a matter of policy and practice for the organisation seeking to recruit.

Reference Checks

It is always better practice to ask for referees from applicants. Generally, reference checks would be undertaken after the applicant is offered the position to protect the applicant’s privacy. Reference checks allow representatives from the organisation to gain independent insights about candidates that relate to their work capabilities. It is most unlikely that a referee supplied by the applicant will not support the application. However, at the same time, asking the right probing questions usually elicits a truthful response from referees. It is worth remembering that the person you are requesting to provide the reference is often busy with their work, so it is important to keep your questions concise and focused on the following:

- the essential skills for the job requirements,

- some of the applicant’s personal attributes, and

- role-specific questions.

The following table contains examples of some questions that address these three important areas.

Possible questions for referees

| Essential Job Skills | Applicant Personal Attributes | Role Specific Questions |

| Please detail the nature of your working relationship with the applicant. | Please describe the applicant’s ability to use initiative when problem-solving. | Please rate and comment on their overall performance. |

| Please confirm the general duties and responsibilities of the role. | Please rate and comment on their verbal communication skills. | How would you rate their customer service skills? (Please explain your answer and provide an example) |

| What do you consider the applicant’s strengths relating to technical skills and personal attributes? | Please rate and comment on their general conduct and behaviour. | Can you comment on the level of supervision they require? How well did they work autonomously? |

| Are you happy for us to contact you for further information, and if so, is there a preferred time or day that would be best for you? | What level of drive and motivation did they display during the time that you worked with them? | Please rate and comment on how they worked with and related to their team and management. |

| Would you re-employ them if given the opportunity and had an appropriate role? | Please rate and comment on their honesty and integrity. | Please rate and comment on their ability to find innovative ways to solve problems |

Activity

Looking for opportunities

Scenario:

Your email inbox contains a request for a written reference for one of your better performing staff members. You had no idea that the staff member applied for a new position and you believed they were happy in their job.

Activity Instructions:

Considering the value of this staff member to you personally and to the organisation, list some lawful and ethical actions that you would take in an attempt to retain them. Think about things such as understanding the reason for why they explored employment options, remuneration level, other benefits, training and development, or professional education options that could be offered. Remember, you can only negotiate within your delegation limits.

Extending an Employment Offer

The employment offer is the final process in the recruitment and selection process. Once the most suitable candidate for the job is determined, it is time to inform the candidate of the pre-employment requirements. These requirements may include background inquiries, drug tests and, if applicable, licensing information, and any other pre-employment requirements such as background and criminal history checks, medical fitness, and so on.

When recruiting for positions where employment terms need to be negotiated, such as compensation and benefits and other issues, a draft employment offer may change based on information from the candidate to the employer until the parties reach an agreement. An employment offer should always be in writing to document the terms of your agreement with your prospective employee. Most importantly, the documents should be executed before the person takes up the position.

Labour Metrics – Measuring Recruitment and Retention Outcomes

There are options to consider that relate to metrics that assist in determining the success of recruitment and retention strategies and processes used to recruit and retain the health and social care workforce. While what is included here is not exhaustive, it contains relevant and achievable evidence-based metrics currently considered within the health and social care sector and the wider workforce management communities. These metrics require scrutiny as to the data sources available to implement them and the usefulness of each metric relevant to individual health and social care organisations.

It is vital that when considering the recruiting metrics, that they have relevance and useability within health and social care organisations. This may mean collecting a smaller data set and resultant metrics than using a large quantity with less impact on the workforce (Fishbein et al., 2019).

The recruitment and retention metrics should also be tied to specific business goals because they will have greater relevance and use within the organisation as one of the strategies used to achieve desired outcomes in line with those business goals. Labour metrics not aligned with strategic and operational business goals will not be as relevant and useful to organisational leaders and talent management specialists who use them.

The process of obtaining a result from workforce data must move beyond just collecting it. When improvements are required, there must be an appropriate analysis of the results compared to action strategies. Health and social care leaders must use these metrics as part of an actionable improvement process to gain the most value. It is recommended that a regular review of recruiting metrics is undertaken. These reviews should:

- occur annually as a minimum,

- be accompanied by a review of the frequency of measure and the quality of data collected, and

- examine the success or otherwise of improvement strategies to ensure that these labour metrics are gathered and used successfully to support improvement.

The focus of these reviews will in provide valuable information related to the following:

- employee recognition and reward strategies, and employee engagement;

- the organisation’s strategic goals; and

- fostering a culture of continuous improvement within the organisation.

It is also vital to choose recruiting and retention metrics that focus on early warning about any issues of concern in the recruitment or retention of the health and social care workforce addressed by strategies that help to improve the results.

The Importance of Sound Recruitment and Retention Results

While finding and employing the right people is critical, retaining them is just as important. There is considerable cost involved in finding the right person for vacant jobs within any health and social care organisation. Losing members of the workforce often incurs prohibitive costs, including losses in revenue, because services cannot be safely offered with an available and appropriately qualified and experienced workforce, causing a decline in productivity. This can even harm staff morale.

Employee retention metrics provide valuable information about why employees stay with the organisation. These can be used to monitor employee retention, identify at-risk employees, and look at trends for what may be expected in the future. Such analyses can help strengthen employee retention strategies and minimise attrition costs. When employee retention is monitored this way, the organisation can assess the level of satisfied employees and use the information to reduce attrition. Providing competitive salaries and wages, training opportunities, and work-life balance are a few ways to improve employee retention rates. Helping employees feel engaged, challenged, and supported so they feel a sense of accomplishment and fulfilment can also boost employee morale and retention. Work is not just transactional for many employees. Engaged workers are more likely to continue their employment, and even become high performers. Helping employees understand their impact on the business can give them a sense of participation and help improve their fulfilment.

From a cost perspective, replacing an employee is expensive , and anecdotally some estimates demonstrate that it could be as much as 50–100% of an employee’s annual salary (Guilding, Lamminmaki, and McManus, 2014). When an employee leaves a position, the employer also loses the time, money, and effort associated with recruiting, hiring, and training them. Additionally, an employee’s departure can damage staff morale, particularly when a highly regarded, long-term employee leaves. This can also affect brand perception. With social media at their fingertips, current and former employees can be valuable brand ambassadors if their experience is positive; however, if their experience is a negative one, the reverse may also be true.

Watch this video “Cost of Employee Turnover”

Video Source: Stream Dental HR. 2019. The True Cost of Employee Turnover. Available at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=c4tZX-p8DSM

Employee retention is the percentage of employees who remain with the organisation for a fixed period. Retention is usually calculated on an annual basis. Retention may also be tracked for specific roles or teams if areas need extra attention. Overall, a good employee retention rate is typically about 90%, and it also needs to be stated that a 100% retention rate is not necessarily desirable. Some of those who leave are the lowest performers, and that can make room for more engaged, higher-performing employees. Good employee retention rates vary by industry. Retention refers to how many employees stay, and turnover refers to how many employees leave. These are two of the most important metrics for any business.

Ways to motivate teams to do their best work should also be examined. Tracking and monitoring retention metrics can explain why employees remain loyal and uncover areas for improvement. Table A describes fourteen (14) recruitment metrics, and Table B describes eight (8) retention, attrition, and turnover metrics for workforce recruitment and retention processes and procedures.

Recruitment and Retention Metrics

The following are all variations from several sources (Pozo-Martin et al., 2017, Green, 2012, Durai D, Rudhramoorthy, and Sarkar, 2019, Russell, Humphreys, and Wakerman, 2012). Tables A and B are a composite of evidence from each of the cited publications rather than any of them coming directly from any one of them.

Table A: Recruitment Metrics for Consideration

| Metric Name | Rationale/Explanation | Formulae | |

| 1 | Time to Fill | The number of calendar days between the fill approval and candidate’s acceptance of the job offer.

Several factors can influence time to fill, such as supply and demand ratios for specific jobs and the speed of the recruitment. Time to fill is a good metric for business planning. It offers a realistic view to assess the time it takes to attract and employ a replacement for a departing employee or to employ against a newly established position. |

Calendar days elapsed from requisition to commencement expressed as an average. |

| 2 | Average Time to Employ (TE) | Time to hire is the days between the candidate’s application and acceptance of the job offer. It is the time the applicant takes to move through the hiring process once they submit their application.

Time to hire provides a solid indication of how the recruitment process is performing. In some literature, this metric is also known as ‘Time to Accept.’ A shorter time to hire prevents better candidates from being employed by an organisation with a shorter time to hire. It also impacts the candidate’s experience by identifying a process that takes a long time (e.g., the data might show a long time between resume screening and the next stage of the recruiting process). The recruiting funnel heavily influences the metric. When hiring for jobs with a straight-forward recruitment process of one interview, the time to hire will be shorter than for a more arduous process, and for this reason, care should be taken when interpreting the data this metric provides. |

The number of days between the candidate’s application and offer acceptance expressed as an average. |

| 3 | Source of Employee (SE) | Tracking the sources that attract new employees is one of the most popular recruiting metrics and assists with monitoring recruitment channel effectiveness. Some examples are organisational job boards (internal or external), a career page, social media, and recruitment agencies.

Having a clear understanding of which channels work and which do not helps to determine the channels creating the most return on investment (ROI). Less time can then be spent on more successful channels; for example, if the job board provides better recruitment than LinkedIn, then that is the channel to focus on. |

No formula required |

| 4 | Candidate First Year Retention Rate (CRR) | First-year attrition or first-year turnover is a key recruiting metric and indicates recruitment success. Candidates leaving in their first year of work often fail to become productive.

First-year attrition can be managed and unmanaged. Managed attrition means that the employer terminates the contract and is often an indicator of bad first-year performance or a bad fit with the team. Unmanaged attrition means that the employee leaves of their own accord and is also referred to as voluntary turnover. This is often an indicator of unrealistic expectations that cause the candidate to quit, which may be due to a mismatch between the job description and the job. |

No formula required |

| 5 | Manager Satisfaction (MS) | Relating to the quality of hire, manager satisfaction with the quality of recruitment is indicative of a successful recruiting process. When the employing manager is satisfied with the new employees in their team, the candidate is likely to perform well and fit well in the team, and the candidate is therefore more likely to be successful. | No formula required |

| 6 | Candidate Job Satisfaction (CJS) | This metric provides information about whether the recruit’s expectations match their experience after commencing the role. If the candidate expresses low candidate job satisfaction, this indicates a mismatch between the candidate’s expectations and experience. | No formula required |

| 7 | Applicants per Job Opening | Many applicants could indicate a high demand for jobs in that area or a job description that is too broad. | |

| 8 | Selection Ratio (SR) | The selection ratio refers to the number of candidates employed compared to the total number of candidates.

This metric is similar to the number of applicants per opening. When there is a high number of candidates, the ratio approaches zero. The reverse is true and provides a good indicator of the value of the various assessment and recruitment tools used. |

Employed candidates

Number of candidates |

| 9 | Cost per Recruitment (CR) | Cost per hire considers the significant costs involved with recruitment. These costs are often divided into internal and external costs.

Internal costs include: compliance costs, administrative costs, training and development, and talent acquisition costs. External costs include: criminal and other background checks, sourcing expenses, travel expenses, and marketing costs. |

Internal costs such as: Advertising, any employment agency costs, candidate expenses, etc.

External costs such as: recruiter costs (average labour costs x hours spent), manager costs (average labour costs x hours spent), recruit onboarding time, lost productivity, and other internal costs. |

| 10 | Candidate experience (CNPV) | Candidate experience is how job seekers perceive an employer’s recruitment and onboarding process and is often measured using a candidate experience survey.

This survey uses a net promoter score and helps identify key components of the experience that can be improved. |

No formula required |

| 11 | Offer Acceptance Rate (OAR) | This metric compares the number of candidates who accepted a job offer with the number of candidates who received an offer. A low acceptance rate means that issues such as pay and conditions or the role as explained in the job description or by the recruiter do not meet the candidates’ expectations. | Number of offers accepted

Number of offers made |

| 12 | Percentage of Open Positions | This is the percentage of open positions compared to the total number of positions that can be applied to specific departments or the entire organisation.

Where a higher percentage of open positions exists in a specific department, this can mean those positions are in high demand (for example, due to fast growth). However, it can also mean that there is currently a low supply of workers for those positions. This metric can offer insights into the current trends and changes occurring in the labour market, which can be valuable when building your talent acquisition strategy. |

Number of open positions

Total number of available positions |

| 13 | Application completion rate (ACR) | This talent acquisition metric shows how many candidates who started a job application finished it. It can also measure the reverse as “applicant drop-out rate”; that is, the share of candidates who did not complete the application.

Application completion rate is especially interesting for organisations with elaborate online recruiting systems. Many large corporate firms require candidates to manually input their entire curriculum vitae or resume in their systems before they can apply for a job. The drop-off in this process indicates problems, for example, web browser incompatibility with the application system or a non-user-friendly interface. This recruiting metric fits well with the following metric (yield ratio). |

No of commenced applications

No of completed applications. |

| 14 | Yield Ratio (YR) | The recruitment process can be seen as a funnel that begins with sourcing and ends with a signed contract. The yield ratio per step is measured by the effectiveness of all the steps in the funnel.

The yield ratio represents the percentage of candidate movements from one part of the hiring process to the next. This metric demonstrates movements between each stage (e.g., from application to screening calls) and from start to finish. |

At each recruitment stage: completed applications

Applicants who entered this stage |

Table B. Retention Metrics for Consideration

| Metric Name | Rationale/Explanation | Formula (where applicable) | |

| 1 | Employee Satisfaction (ES) | Organisations are more likely to retain satisfied staff than those who are not.

An employee survey often achieves this, which can help measure employee satisfaction. A common metric used is the net promoter score (NPS) used to gauge satisfaction which is based on a Likert scale response to a question such as:”How likely are you to recommend this organisation to a friend or colleague as a good place to work?” Likert Scale: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Not Likely – Extremely Likely |

% of promoters – % of detractors |

| 2 | Overall Retention Rate (ORR) | This refers to the organisation’s ability to retain employees over a period of time.A good overall retention rate might hover around 90%.

Remember, there is always room for some turnover. Turnover can allow for refreshing the workforce with employees who possesses desirable and useful skill sets.The turnover rate is a good companion to this metric. |

For a specific time period: employees retained x 100 total employees |

| 3 | Overall Turnover Rate (OTR) | The percentage of separations, or employees who leave, either voluntarily or involuntarily.

A high turnover rate directly affects productivity and makes it difficult to attract top talent, which can indicate leadership or organisational culture problems. |

For a given time period:

Number of separationsaverage number of x 100 |

| 4 | Voluntary Turnover Rate (VTR) | Voluntary turnover rate is the percentage of employees deciding to leave a job, but what causes high employee turnover?

It is typically a variety of reasons, such as switching to another job or retiring.Because these employees are more skilled than those who leave involuntarily, and they tend to cost more to replace. |

For a given time period:

Voluntary separations average no. of employees x 100 |

| 5 | Involuntary Turnover Rate (IVR) | The involuntary turnover rate is the percentage of people fired or laid off in a given period. The higher the involuntary turnover rate, the more urgent it is to evaluate the employment processes to avoid future mis-hires. | For a given time period:

Involuntarily separations Average no. employees x 100 |

| 6 | Employee Absence Rate (EAR) | This indicates unplanned employee absences for sickness, personal emergencies, or other unanticipated reasons. | For a given time period:

Unexpected absences Total workdays x 100 |

| 7 | Retention Rate per Manager (RRM) | This metric demonstrates the percentage of employees who remain in their jobs under an individual manager or team. | Staff terminated/manager

total staff per manager x 100 |

| 8 | Turnover Costs (TC) | These costs include termination of employment costs, salary sacrifice or other benefit costs and productivity costs. This is not a good benchmark indicator, because costs will vary in different organisations due to their different recruiting cost structures. | Sum of variables associated with turnover x total number of employees who leave |

The real value of these metrics lies in analysing these data to inform process control and identify improvement areas. These metrics reduce an overly complex phenomenon to numerical data that has practical use. However, the development of trend data and upper and lower control limits to measure variation further enhances this to the extent that quantitative data can. A deeper understanding of the reasons why the metrics return the results they do will require qualitative analysis. There is also a need to consider what qualitative data may be gathered to gain a more in-depth understanding of the employee perspective that can be thematically analysed using proven methods to achieve this, which is the subject of further enquiry not discussed here.

Activity

From the suite of recruitment and retention metrics provided in this chapter, select three recruitment and retention methods that you assess as being the most valuable for the organisation in which you work (if you are not working, then think about an organisation in which you have previously worked, or one for which you would like to work).

Select three recruitment and two retention methods, and record them in a column labelled ‘metric’. In a column labelled ‘rationale’, state why you believe the metric is included in the ‘top five’.

When selected, each metric consideration must be given to the availability of the data to calculate the metric, how the results could be applied to solving the weighty issue of workforce availability and sustainability, and the benefits of having trend over time data for the metric would provide.

Key Takeaways

Talent management is a series of processes, including the important functions of attracting, recruiting, and retaining talent.

There are many sources or ‘channels’ to attract candidates for jobs. Success lies in knowing which channels deserve additional effort and attention.

Organisational brand is an important variable in attracting, recruiting, and retaining a workforce. Treat all applicants well, even those who were unsuccessful, and provide advice as to the outcome of their application and feedback on their performance if requested.

Reviews on the various types of psychometric testing are mixed.

Selection panel chairs and members require ongoing training and development to ensure that organisational policies are upheld and that merit is applied in all processes.

There are many formulae for recruitment and retention metrics. The metrics are most successful when they are based on reliable data, sound analyses, and they are used to inform actions that trend over time data suggests.

References

Castro Lopes, S., Guerra-Arias, M., Buchan, J., Pozo-Martin, F. and Nove, A. 2017. A rapid review of the rate of attrition from the health workforce. Hum Resour Health, 15, 21.

Durai, D. S., Rudhramoorthy, K. and Sarkar, S. 2019. HR metrics and workforce analytics: it is a journey, not a destination. Human Resource Management International Digest, 27(1), pp.4-6.

Dussault, G. and Zurn, P. 2020. Health labour markets: An overview of some human factors that influence demand and supply. European Journal of Public Health, 30.

Fishbein, D., Nambiar, S., McKenzie, K., Mayorga, M., Miller, K., Tran, K., Schubel, L., Agor, J., Kim, T. and Capan, M. 2019. Objective measures of workload in healthcare: a narrative review. Int J Health Care Qual Assur, 33, 1-17.

Glassdoor. 2023. Discover your workplace community. Available: https://www.glassdoor.com.au/member/home/index.htm

Green, P. S. 2012. HR Group Creates Workforce Metrics. Bloomberg Businessweek, 1.

Guilding, C., Lamminmaki, D. and McManus, L. 2014. Staff turnover costs: In search of accountability. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 36, 231-243.

Hoppe, D. 2018. Linking employer branding and internal branding: establishing perceived employer brand image as an antecedent of favourable employee brand attitudes and behaviours. Journal of Product and Brand Management, 27, 452-467.

Klimek, P., Gyimesi, M., Ostermann, H. and Thurner, S. 2020. A parameter-free population-dynamical approach to health workforce supply forecasting in EU countries. European Journal of Public Health, 30.

Mitosis, K. D., Lamnisos, D. and Talias, M. A. 2021. Talent Management in Healthcare: A Systematic Qualitative Review. Sustainability [Online], 13.

Nangoli, S., Muhumuza, B., Tweyongyere, M., Nkurunziza, G., Namono, R., Ngoma, M. and Nalweyiso, G. 2020. Perceived leadership integrity and organisational commitment. Journal of Management Development, 39, 823-834.

Naulleau, M. 2019. When TM strategy is not self-evident. Management Decision, 57, 1204-1222.

Papa, A., Dezi, L., Gregori, G. L., Mueller, J. and Miglietta, N. 2018. Improving innovation performance through knowledge acquisition: the moderating role of employee retention and human resource management practices. Journal of Knowledge Management, 24, 589-605.

Pozo-Martin, F., Nove, A., Lopes, S. C., Campbell, J., Buchan, J., Dussault, G., Kunjumen, T., Cometto, G. and Siyam, A. 2017. Health workforce metrics pre- and post-2015: a stimulus to public policy and planning. Human Resources for Health [Online], 15.

Risavy, S. D. and Hausdorf, P. A. 2011. Personality testing in personnel selection: Adverse impact and differential hiring rates. International Journal of Selection and Assessment, 19, 18-30.

Russell, D. J., Humphreys, J. S. and Wakerman, J. 2012. How best to measure health workforce turnover and retention: five key metrics. Australian Health Review, 36, 290-5.

Santos, A. S., Reis Neto, M. T. and Verwaal, E. 2018. Does cultural capital matter for individual job performance? A large-scale survey of the impact of cultural, social and psychological capital on individual performance in Brazil. International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management, 67, 1352-1370.

Scepura, R. C. 2020. The Challenges With Pre-Employment Testing and Potential Hiring Bias. Nurse Leader, 18, 151-156.

Stream Dental HR. 2019. The True Cost of Employee Turnover. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=c4tZX-p8DSM

Terry, D. R., Peck, B., Smith, A., Stevenson, T. and Baker, E. 2019. Is nursing student personality important for considering a rural career? Journal of Health Organization and Management, 33, 617-634.

Van Den Broek, J., Boselie, P. and Paauwe, J. 2018. Cooperative innovation through a talent management pool: A qualitative study on coopetition in healthcare. European Management Journal, 36, 135-144.

Van Den Heede, K., Cornelis, J., Bouckaert, N., Bruyneel, L., Van De Voorde, C. and Sermeus, W. 2020. Safe nurse staffing policies for hospitals in England, Ireland, California, Victoria and Queensland: A discussion paper. Health Policy, 124, 1064-1073.

Videojug. 2011. How to Interview Candidates for a Job. https://youtu.be/d6uzZqkcsa8

Wadhwa, S. and Tripathi, R. 2018. Driving employee performance through talent management. International Journal of Environment, Workplace and Employment, 4, 288-313.

Ybema, J.F., van Vuuren, T. and van Dam, K., 2020. HR practices for enhancing sustainable employability: Implementation, use, and outcomes. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 31(7), pp.886-907.

Yohn, D. L. 2020. Brand authenticity, employee experience and corporate citizenship priorities in the COVID-19 era and beyond. Strategy and Leadership, 48, 33-39.