Organisation and governance

Innovation and performance in health and social care organisations

Sheree Lloyd and Karrie Long

Introduction

In Australia, the sustainability of our health system is of increasing concern as the population ages and the burden of chronic disease increases. The global COVID-19 pandemic disrupted health services and the way we work and deliver healthcare. The pandemic demonstrated that when there is a pressing real-world problem to solve, we can innovate at speed (Palanica and Fossat, 2020) and collaborate to develop new products, adapt to technologies, and integrate them into our daily practices. Changing patient needs, technological advances, budgetary cuts, sustainability issues, the growth in chronic diseases, and an unstable operational landscape have been identified as drivers for innovation in the health sector (Akenroye, 2012). The health and social care industry is highly educated and professionalised, and clinicians and professionals have many ideas about how to improve practices and models of care to deliver safer, more efficient, and effective services. Akenroye (2012) cited Don Berwick’s observation that it is not the scarcity of innovation in health, but the adoption and dissemination of innovative concepts that are the problem.

The pursuit of innovation is on the agenda of countries worldwide and is identified as a key driver of growth, well-being and productivity (OECD, 2015). Innovation can also contribute to solving core public policy challenges in health, education and issues with food security, the environment and public sector efficiency (OECD, 2015). Key challenges relating to the ageing population and climate change could be solved through innovation-led approaches (OECD, 2015). Innovative digital technologies can provide new options for the delivery of care (see digital health chapter). The World Health Organization (WHO) (2021) recognises the value of digital health innovation to support the achievement of the Sustainable Development Goal (Good Health and Well-being). In Australia, the opportunities to utilise the power of technology and promote innovation to support high-quality, sustainable health, and care for all have been clearly outlined in digital health and other strategic documents (Australian Digital Health Agency, 2018). Phasing out obsolete practices and adopting innovation are fundamental drivers of high-quality and sustainable healthcare (Balas and Chapman, 2018).

This chapter will also examine the concept of health system performance. A health system can be regarded as performing well at the population level if the population is leading long and healthy lives, there is low infant mortality and disease-specific morbidity, and mortality is improved over time through targeted interventions and public health campaigns. Access and equity are also used as measures of performance (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2022c). Indicators of health system performance that reflect access to healthcare in geographic locations, services provided, and hospital beds by population ratios are examples of possible measures. Examining the safety and quality of care delivered to patients is also an indication of performance. Measures such as waiting times, access to care and consumer satisfaction are used to understand the safety and quality of a healthcare setting. Health services will not be effective without a workforce that is available at the right place, at the right time, with the necessary skills. As the sustainability of our healthcare system is important, we can also evaluate performance based on financial indicators such as cost per patient, average length of stay, and budget variances. Finally, the availability of equipment, treatment centres, supplies, and medicines can also determine effectiveness and performance.

Innovation and innovation theory

The topic of innovation is vast, and innovation has been of interest since the 1770s, with new ways of business emerging (Salter and Alexy, 2013). Innovations that are sustained usually make an improvement to the way that ‘things are done’. This is true in the health sector, where innovations will be sustained if new methods make work easier or reduce workloads. Innovation has been studied at the industry, firm, and individual levels, and many factors impact the uptake and sustainability of innovation and innovation behaviours (Damanpour, 1996; Greenhalgh et al., 2005). We often think of innovations as new technologies or breakthroughs; however, the literature reveals that there are many different types of innovation. Innovations may be new products, processes or services, technologies, organisational structures or administrative systems, or new policies, plans or programs (Damanpour, 1996). Importantly, new ideas should be directed at improving health outcomes, cost-effectiveness, administrative efficiency, and user experiences, and implemented through coordinated and deliberate actions (Greenhalgh et al., 2004).

In Australia, the health industry provides millions of services each year in general practices, hospitals, pathology and imaging centres, pharmacies, aged care, primary health, and other settings (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2022a). Service innovation has wide appeal and application in health, and the potential to have a huge impact. Service innovations may involve improvement in the way healthcare services are delivered and organised; for example, the use of novel technology, new medical procedures, the introduction of new services, new care pathways or models of care, or the crafting of new professional roles (e.g. medical or allied health assistants) (Scarbrough and Kyratsis, 2022). Johannessen (2013) noted that service innovation has two categories – tangible and intangible service products. In the health industry, this may be new treatments or models of care, and intangible products, such as change of attitude, change in service experiences for patients and consumers, or change in communication styles or methods. Examples of innovation in health are the adoption of checklists to reduce infections (Pronovost, 2008), hospital and rehabilitation in the home, day of stay surgery, e-government, and of course, technological innovation such as artificial intelligence, the metaverse, and robotics (see Digital Health chapter). These innovations have reduced complications, allowed hospitals and healthcare settings to manage increased demand for services, reduced length of stay, and provided greater accessibility through enabling technology such as teleconsultations.

Schumpeter, who is identified as the father of the study of innovation, suggested that most innovations are combinations of elements that already exist (Salter and Alexy, 2013). This may involve the development of new technologies and processes or ways of organising. Innovation may be transformative or incremental, and the literature outlines the strengths and weaknesses of each approach (Dobni, Klassen, and Nelson., 2015; Witell et al., 2016). Incremental innovations can have significant effects (Johannessen, 2013; Salter and Alexy, 2013). Over the last decade, in the Netherlands, innovations to primary care funding and the introduction of primary care physician cooperatives have been successful in satisfying patients’ needs for after-hours care, with 90% of patients visited in their homes within an hour of calling and a reduction in incidents of suboptimal treatment (Snowden and Cohen, 2012).

Damanpour (1996), a seminal writer on innovation, noted that empirically developed theories of organisational innovation are not adequately descriptive “despite continued scholarly effort in the past three decades to understand both the innovation process and the conditions under which innovation is facilitated”. Rogers’ model of innovation adoption has been widely used over the past 30 years, and is still applied today, despite the theory being first described in 1962 (Kaur Kapoor et al., 2014; Pashaeypoor et al., 2016; van Oorschot, Hofman, and Halman, 2018). Rogers’ innovation adoption curve with early adopters and laggards is widely known (Rizan et al., 2017), and still taught in health and business schools. Studies have described how the health industry disseminates innovation, the processes for adoption, the determinants and antecedents for innovation (Chaudoir, Dugan, and Barr 2013; Crossan and Apaydin, 2010; Fleuren, Wiefferink, and Paulussen, 2004), and the factors that support innovation uptake and spread (Greenhalgh et al., 2004, 2005). Early work by Greenhalgh (2005) on innovation dissemination in health continues to be extensively referenced (Kaur Kapoor et al., 2014; National Health System, 2018; Rapport et al., 2018; van Oorschot, Hofman, and Halman et al., 2018) and is recognised as a significant and seminal work. Some aspects have been updated in her more recent work (Greenhalgh et al., 2010, 2017; Greenhalgh and Abimbola, 2019; Greenhalgh and Papoutsi, 2019).

Exercises

Watch this short video on innovation in health care. Consider your own work area and think about ideas where innovation could lead to solutions.

Innovation in Health Care created Canada Health Infoway. Source : https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5yRKcZzaLA4

Determinants and antecedents of innovation

Successful innovation involves several factors. Different models and frameworks for innovation in the literature explain how innovation occurs. Rao and Weintraub (2013) described six building blocks of an innovative culture; resources, processes, values, behaviours, success, and climate. Others have found that the propensity for innovation is a more complex multidimensional construct grounded in service, process, cultural, and infrastructure aspects (Chaudoir, Dugan, and Barr 2013; Dobni, 2008). To foster innovation resources, processes and the measurement of success should be given attention, but we should also understand the harder-to-measure and people-oriented determinants of innovative cultures such as values, behaviour, and organisational climate (Rao and Weintraub, 2009, 2013).

Whilst some resourcing to support time for thinking, planning, and implementing innovation is required, the effectiveness of innovation depends on the organisational context – culture, leadership, and team dynamics (Phillips, 2013; Harrison et al., 2014; Körner et al., 2015). These factors can be more important underpinnings for innovation than resourcing (Rao and Weintraub, 2013).

A seminal literature review that synthesised more than 1,000 papers found that in health service delivery organisations certain structural determinants have a positive and significant association with organisational innovativeness (Greenhalgh et al., 2004, 2005). The conceptual model derived for the diffusion, dissemination, and implementation of innovation describes the system antecedents for innovation, innovation specific implementation process, readiness for innovation, and other factors. The devised model was then tested on four case studies (Greenhalgh et al., 2004) and has been elaborated upon in later work (Greenhalgh et al., 2017). The conceptual model suggests that an organisation will adopt innovations more readily if it is large (in size), is functionally differentiated into small autonomous departments, is mature, has high-quality data systems and strong leadership with a clear vision, and has resources to channel into innovation and decentralised decision-making processes. Greenhalgh et al. (2004, 2005) explained that large size and organisational complexity promote the adoption of innovation, as these determinants enable specialised expertise to develop and that there are critical masses of problems that demand solutions. Similarly, environments that are changing or heterogenous facilitate innovations, as these organisations and their cultures are exposed to new ideas imposed from outside, in contrast to stable environments (Greenhalgh et al., 2005).

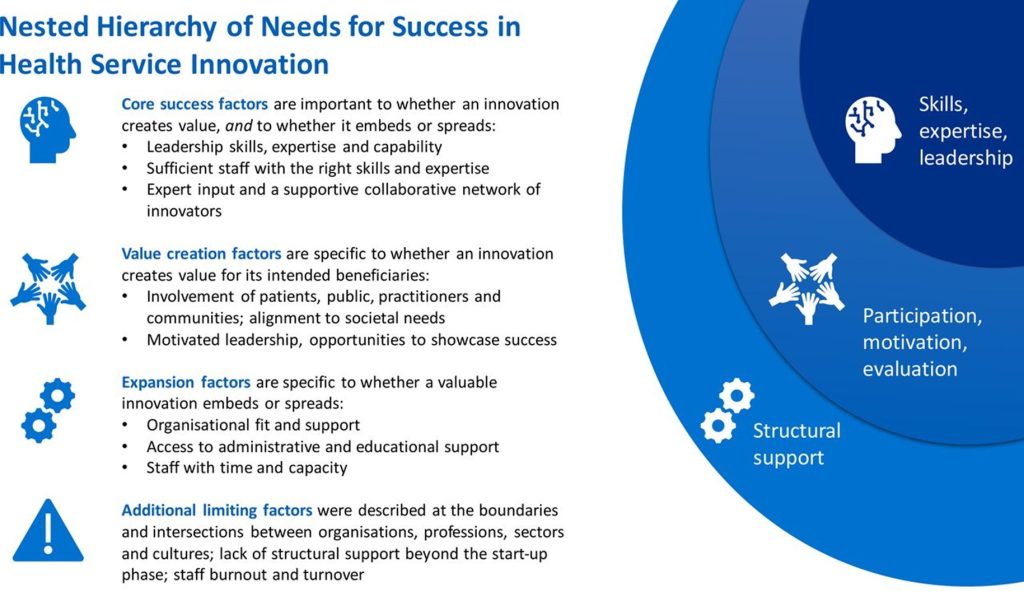

A study by Leedham-Green, Knight, and Reedy (2021) found that service level innovations in healthcare contexts required a number of critical success factors, including:

- Supporting innovators with the rights skills and experience, including implementation and leadership skills and evaluation expertise.

- Recognising and reinforcing the importance of collaborative and participatory approaches to align to organisational, societal, practitioner, community, and consumer goals.

- Providing opportunities to demonstrate the success of innovation projects amongst networks, colleagues and peers, building a community of support and expertise

- Supporting innovators with administrative and educational support.

Many healthcare organisations have implemented innovative practices only to see abandonment or incomplete implementation (Greenhalgh et al., 2017; Scarbrough and Kyratsis, 2022). A Canadian study found that fewer than 40% of health care improvement initiatives successfully transitioned from adoption to sustained implementation and spread to more than one health care organisation (Scarbrough and Kyratsis, 2022).

Diffusion (passive spread), dissemination (active and planned efforts to persuade target groups to adopt an innovation), implementation (active and planned efforts to mainstream an innovation within an organisation), and sustainability (making an innovation routine until it reaches obsolescence) are terms used to describe innovation spread (Greenhalgh et al., 2004, 2005).

Activity

Read this paper.

From spreading to embedding innovation in health care: Implications for theory and practice (Scarbrough and Kyratsis, 2022)

Click here to access the paper

Consider the policy and practice implications for embedding innovation. Jot down three key points.

You can also listen to a podcast here where this paper is discussed by Cathy Balding and Cathy Jones and note three key points.

Context and the role of place in innovation

The literature reports that organisational context influences the adoption of innovative technologies (Greenhalgh et al., 2017). Context was demonstrated to shape the change outcomes of e-health implementations in rural settings in a study by Hage et al. (2013). Their study aimed to identify implementation factors that enable or restrain the adoption of e-Health and concluded that new technology innovations to support rural health sustainability can fail “due to underestimating the implementation factors involved and the interactions between context, process and content elements of change” (Hage et al., 2013).

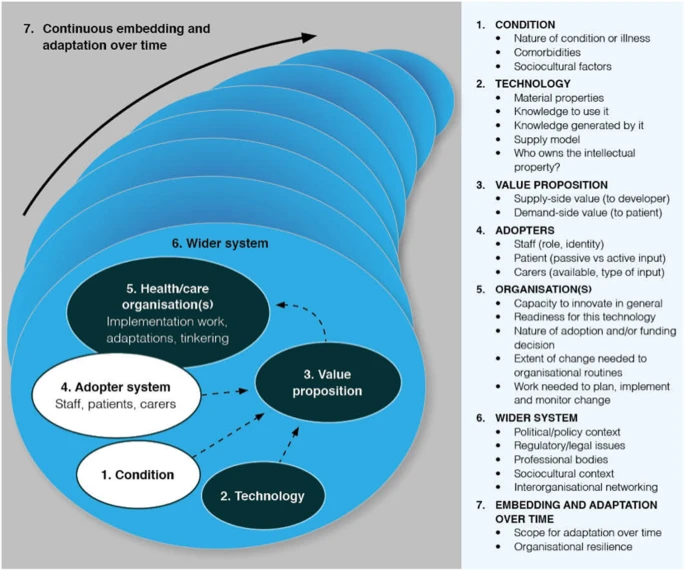

Greenhalgh and Abimbola, (2019) developed a tool for determining and understanding context and the complexities involved when implementing health interventions and technologies. Their Non-adoption, Abandonment, Scale-up, Spread, and Sustainability (NASSS) framework acknowledges that success is dependent upon the context, factors relating to the technology itself, and the wider context in which it is implemented (Greenhalgh and Abimbola, 2019), as depicted below.

As noted, all organisations have unique cultures (Braithwaite et al., 2018) that will impact upon their performance and ability to innovate. Contextual factors have been shown to influence the implementation of patient safety interventions (Kringos et al., 2015; Ovretveit et al., 2011; West and Lyubovnikova, 2013).

Activity

Read the paper Nurturing innovative culture in a healthcare organisation – Lessons from a Swedish case study by Andersson et al., (2022)

Click here to access the paper.

Answer the following questions:

Why are relationships inside and outside of health an important enabler of innovation?

What is the role of leaders?

The link between performance and innovation

‘It is essential that health care delivery systems innovate at scale to optimise performance. Achieving successful and sustainable improvements across complex health systems is, however, difficult.’ (Wutzke, Benton, and Verma, 2016)

Health care is complex, and hospitals have distinctive characteristics compared to other industries (Lee, 2015; Wutzke, Benton, and Verma, 2016). Lee (2015) conveyed that hospitals aim to provide the best services to patients and employees, improve operational efficiency, reduce costs, and apply advanced technologies to internal and external functions.

Evidence linking innovation to performance is scant (Dias and Escoval, 2013). Surprisingly, “little is known about the nature of innovativeness in healthcare organisations and its relationship with performance” (Moreira, Gherman, and Sousa, 2017). Mafini (2015) conducted research in a public organisation and demonstrated a strong positive relationship between organisational performance and innovation, and inter-organisational systems and quality. Crossan and Apaydin, (2010) stated that ”linking innovation outcomes with performance is critical in addressing whether and how innovation creates value”. They cited other management scholars and related that “innovation capability is the most important determinant of firm performance” (Crossan and Apaydin, 2010).

Dias and Escoval (2013) critically analysed the relationships between innovation and performance in the public health system in Portugal and explored the drivers of performance improvement through innovation. Their study used a range of techniques, including a survey, interviews, and nominal group technique to better understand the relationship between innovation and organisational performance. A conceptual framework was used in their study and included the variables of flexibility, innovation and performance(Dias and Escoval, 2013). The study suggested that the factors necessary to improve performance through innovation in the public health sector were organisational, financial, and cultural changes(Dias and Escoval, 2013). The authors concluded that it is possible to improve performance through different organisational structures and processes, but that certain organisational principles are also required, including an emphasis on the breakdown of hierarchical structures, fostering cooperation across departments, and prominence given to the delegation of authority (Dias and Escoval, 2013).

Measurement of performance

Protecting patients from harm and ensuring that our hospitals, primary care, aged, and social care settings are delivering safe care at a cost that is acceptable to payers and sustainable in an environment of rising demand for health care services is on the agenda of many health and social care organisations (Australian Commission on Quality and Safety in Healthcare, 2021; Board and Watson, 2010; Chalmers, Ashton, and Tenbensel, 2017). Hospitals can be assessed through measurement of performance against agreed standards and comparison with peers.

A shared understanding or common use of a definition of high performance with respect to a healthcare delivery system or the components of a delivery system, including hospitals, clinics, or nursing homes is yet to be determined (Ahluwalia et al., 2017). In a regular report, the Commonwealth Fund compares the performance of healthcare systems for high-income countries using measures that reflect access to care, care process, administrative efficiency, equity, and healthcare outcomes (Schneider et al., 2021).

Activity

Visit this web-page and read the report Mirror, Mirror 2021: Reflecting Poorly Health Care in the U.S. Compared to Other High-Income Countries

Note the high performing and lower performing countries across a range of performance indicators

Public reporting of health information for transparency, accountability, and for clinicians to action to improve care is well recognised (Board and Watson, 2010). In Australia, health information is routinely reported by the Australian and state governments (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2022c; Bureau of Health Information, 2022). Internationally, performance reporting has been shown to exert a powerful effect on accelerating improvements in health services (Canaway, Bismark, Dunt, Prang, et al., 2018a; Leeb, 2018). Much has been written in the literature about the types of performance indicators used, barriers to indicator collection, disincentives to reporting, and how the information can be used (Canaway, Bismark, Dunt and Kelaher, 2018a, 2018b; Canaway et al., 2017a, 2017b)

There are a range of definitions for ‘performance’; however, no single definition of what ‘high performance’ constitutes was able to be identified during the literature review. While there was no singular definition of what performance in health is, or agreed measures (Ahluwalia et al., 2017; Pronovost, 2017), three definitions were considered. Pronovost (2017) suggested that a high-performing health system is one that can achieve its purpose. Dias and Escoval (2013) conveyed that hospital performance may be defined according to the achievement of specified targets, either clinical or administrative; while Taylor et al. (2015, p. 1) used the definition that “High performing hospitals consistently attain excellence across multiple measures of performance and multiple departments”.

In Australia, all public hospitals collect and contribute data to state and national data sets, and this performance data is routinely reported on sites such as the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, NSW Bureau of Health Information and My Hospitals. Australia’s health system performs well when measured against other health systems (Philippon et al., 2018). Since 2009, in Australia, a National Health Performance Framework has been in place that routinely measures the performance of hospitals against measures of equity, quality, safety, appropriateness, and effectiveness (Australian Institute of Health Innovation University of NSW, 2013). While Australia has strong health data collection and data sets, there is no single data collection to determine whether our health system works in optimal ways (Srinvasan et al., 2018).

In summary, the measurement of performance in health using a range of indicators is now an accepted practice in Australian and other countries. Public performance measures are routinely reported through the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare website and organisations such as the Bureau of Health Information in NSW (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2022b; Bureau of Health Information, 2022). This is the picture internationally, as well with Hibbert et al. (2015) who identified 34 organisations from 12 countries as having key roles in healthcare performance and public reporting.

Activity

To ensure that the Australian Healthcare system provides safe and high-quality care the National Safety and Quality Health Service Standards provide a consistent statement of the level of care that consumers should expect.

Visit the webpage and determine the available resources.

The Bureau of Health Information regularly reports on the performance of the NSW healthcare system. Visit the website and select a hospital and examine performance around consumer satisfaction, waiting times, and other indicators.

Poor performance has led to Royal Commissions and reports on failures. Visit the Victorian Department of Health, Targeting Zero site for further information and resources

Aboumatar et al. (2015) conducted a national study of high-performing hospitals with a focus on patient-centred hospital care. The study reported that leaders and clinicians actively worked together in the high-performing organisations studied. Further, organisational context and culture emerged as a common theme in their study, and were noted to be linked to success in high-performing hospitals. The study identified selected approaches to drive improvement, including the use of data, communication strategies such as rounding, hospital-wide education programs, recognition of high-performance teams, incentives for high performance, and development of new hiring policies (Aboumatar et al., 2015). Braithwaite et al. (2018) suggested that hospital performance is related to the pace of hospital life as measured by the length of stay, patient satisfaction, and adverse events. Their article argues that to achieve the best performance, hospitals need to work under conditions of intermediate pace, what they referred to as the ‘Goldilocks’ zone, and they are undertaking further research to validate their theory (Braithwaite et al., 2018).

Integrating research evidence into practice and using data and experience to learn and improve are key to the performance and sustainability of healthcare systems and a learning health system (Agency for Healthcare Quality and Research, 2019). The goal of a learning health system is to create a cycle of continuous learning, improvement, and innovation that leads to better healthcare outcomes, lower costs, and a more efficient and effective healthcare system (Pronovost et al., 2017).

In Australia, accreditation is a widely adopted system for certifying the quality of healthcare organisations. This is a compliance against standards-based rather than an outcome-based approach or performance based approach. Bodies such as the Australian Council on Healthcare Standards survey healthcare organisations according to National Safety and Quality Health Service Standards (Australian Commission on Quality and Safety in Healthcare, 2018). The value of accreditation and linkage to performance was noted in the literature review (Accreditation Canada, 2015; Braithwaite et al., 2010; Greenfield & Braithwaite, 2008). A study by Braithwaite et al., (2010) observed that leadership behaviours and cultural characteristics show a positive trend between accreditation and clinical performance. The standards delineated by the Australian Commission on Quality and Safety in Healthcare focus on systems and processes that will reduce harm and drive high-quality health outcomes (Australian Commission on Quality and Safety in Healthcare, 2021).

Taylor et al. (2015) used the definition that “high performing hospitals consistently attain excellence across multiple measures of performance, and multiple departments”, and undertook a qualitative systematic review of the literature to identify high-performance hospitals and what ideas and factors are important for success. Their study utilised a “range of process, output and outcome and other indicators to identify high performing hospitals” (Taylor et al 2015, p. 1). The study identified seven themes that represent key factors associated with high performance; “positive organisational culture, senior management support, effective performance monitoring, building and maintaining a proficient workforce, effective leaders across the organisation, expertise-driven practice and interdisciplinary teamwork” (Taylor et al., 2015, p. 7).

In contrast, a study by Shwartz et al. (2011) demonstrated that there are challenges in identifying high-performing hospitals and warned that composite measures of performance that take into account multiple components may not recognise individual strengths and strategic priorities of individual organisations. Their study argued that when using multiple performance measures, only a small number of hospitals can clearly be classified as high performing. Their research concluded that “despite the lack of correlation among widely available hospital performance measures, it is still reasonable to calculate a composite measure of performance” (Shwartz et al., 2011).

Studies across industries also suggest that the systematic use of high-performance work practices could improve the quality of care in healthcare organisations (Garman et al., 2011; McAlearney et al., 2013). Garman et al. (2011) and McAlearney et al. (2013) described the concept of high-performance work practices as those practices that have been shown to improve the capacity to attract, develop, and retain high-performing personnel. These practices include performance-driven reward and recognition; information sharing; communicating mission, vision and values; mentoring; teams; and decentralised decision-making with training linked to organisational goals (Garman et al., 2011; McAlearney et al., 2013)

Challenges in performance measurement

Several authors have identified concerns with performance measures and measurement practices that can lead to dysfunctional and unintended consequences (Lynch, 2015; Mannion and Braithwaite, 2012). International studies have found that while performance measurement is important and can have benefits such as reducing waiting times, they can lead to unplanned outcomes in health care organisations such as bullying and gaming misplaced incentives, and they should be interpreted considering ‘local contexts’ (Aryankhesal et al., 2015).

Shahian et al., (2016) observed that some performance cards are flawed and that this fosters cynicism and distrust of performance measurement in general. Their article notes that patients and providers deserve transparent performance measures that are valid, and that doctors and hospitals should be held accountable for the care they provide. Flawed measures are meaningless and may harm health stakeholders, including patients (Shahian et al., 2016). The findings are supported by (Mannion and Braithwaite, (2012), who concluded that performance measurement can be strengthened by the inclusion of different types of measures (process, structure, clinical outcomes, appropriateness, resource use, patient-reported outcomes, and experience of care), data sources (registry, electronic health record), data quality, attribution of patients to specific providers, robust risk adjustment, presentation formats, and the ability to monitor for unintended adverse consequences (Shahian et al., 2016).

While data quality and integrity may be challenges to performance measurement, considerable work on measurement and data quality has occurred and Board and Watson, (2010) and Hanson (2011) argued that we need to use the abundant information available to elucidate quality issues, which will result in better data to inform and improve the quality of health care in Australia (Hanson, 2011).

Public reporting of hospital performance data to increase healthcare provider accountability and transparency so that consumers can make decisions about their health is now routinely available. Public reporting is also intended for doctors, nurses, academics, health service managers, journalists, and the community (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2022b). The unintended consequences of public reporting, such as gaming, the pursuit of short-term targets, deliberate manipulation of data, the need for clarity and different reports depending on the intended audience, and the need for timely data need to be considered and addressed (Freeman, 2002; Hibbert et al., 2015).

Accreditation and standards-based measures

Internationally, many examples of standards-based processes are used to assess healthcare systems; however, these are primarily focused on safety and quality performance and have been comprehensively documented and well-argued (Accreditation Canada, 2015; Greenfield et al., 2015, 2019). Some examples are shown in the table below.

| Description | Country |

| National Safety and Quality Healthcare Standards developed by the Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Healthcare (ACSQHC). | Australia/International |

| Baldridge Performance Excellence (Foster et al., 2007; National Institute of Standards and Technology, 2016; Shields and Jennings, 2013) | United States/International |

| Accreditation Canada Healthcare Standards (Accreditation Canada, 2022) | Canada |

| Accreditation standards Joint Commission on Accreditation in Healthcare (2023) | United States/International |

| Health Assessment Europe (2023) | Europe |

Accreditation and Standards-based measures for assessing healthcare system performance

Safe and high-quality healthcare delivery is extremely important; however, as we have described, performance is a multi-dimension concept. Performance measurement requires a comprehensive picture that considers health outcomes, safety and quality of care, financial performance, access and equity, workforce and availability of resources (medicines and equipment), and treatment settings.

The take home messages on high-performing health care systems are that they are characterised by:

- Consistent leadership that works towards common goals across the organisation.

- Development of leadership skills and enhancing system governance, accountability and performance measurement.

- Engaging clinicians and professional cultures.

- Quality and system improvement, embedded as a core strategy and investment made to support improvement.

- Organisational skills and capacity to support ongoing performance improvement.

- Being at the centre of the health delivery system are strong and robust primary health care teams.

- Patients, caregivers, and the public are engaged in and with the design of healthcare.

- Integration of care that promotes transitions from one sector to the other.

- Information as a platform for guiding improvement.

- Learning strategies and methods to test, pilot and scale up improvements that work.

- Support by leaders for an enabling environment and commitment to changes relating to improvement (Baker, 2011; Baker and Axler, 2015).

Summary and implications

The contextual and organisational factors for innovation have been described in this chapter. Performance measurement in health is topical, and there is continued appetite for using hospital performance data to drive improvements and increase transparency (Canaway, Bismark, Dunt, Prang, et al., 2018b; Canaway, Bismark, et al., 2017). This is enabled as we increase the use of digital solutions and implement new health information systems and technologies.

This chapter outlined why health system managers and funders are focussing on innovation and performance. The chapter identified the determinants of innovation and high performance within health organisations and an understanding of the role of context in the uptake and adoption of innovative practices. Context has been identified as an important influence on the dissemination of innovation and sustainability.

Key Takeaways

You will know you are successful if…

The research evidence suggests the following are critical success factors if organisations and policymakers in the health and social care industries want to support service-level innovation.

- The innovations selected for implementation provide value or benefits to the intended beneficiaries.

- The organisation supports safe innovation and empowers those with ideas to improve services to initiate ideas within resourcing constraints. Time and resources are provided to implement and evaluate innovation, and to avoid burn-out and turnover (Leedham-Green, Knight, and Reedy, 2021).

- Leaders are committed to the identified innovation and there are sufficient staff with the right skills and expertise to drive the implementation of the innovation.

- Resources, education, and time are made available to reflect on how improvement and innovation can ensure care is safer, less interventional, more cost-effective, involves consumers, and implements these innovative ideas using appropriate change and project management initiatives (Greenhalgh and Abimbola, 2019; Greenhalgh and Papoutsi, 2019; Leedham-Green, Knight, and Reedy, 2021).

References

Aboumatar, H. J., Chang, B. H., Al Danaf, J., Shaear, M., Namuyinga, R., Elumalai, S., Marsteller, J. A. and Pronovost, P. J. 2015. Promising practices for achieving patient-centered hospital care. Medical Care, 53(9), pp.758-767.

Accreditation Canada. 2015. The Value and Impact of Health Care Accreditation : A Literature Review. Accreditation Canada.

Accreditation Canada. 2022. Home. Available at: https://accreditation.ca/hospitals-and-health-systems (accessed 16 January 2023).

Australian Council on Healthcare Standards. 2018. Who we are. Available at: https://www.achs.org.au/about-us (accessed 30 November 2018).

Agency for Healthcare Quality and Research. 2019. About Learning Health Systems. Available at: https://www.ahrq.gov/learning-health-systems/about.html (accessed 3 March 2023).

Ahluwalia, S. C., Damberg, C.L., Silverman, M., Motala, A. and Shekelle, P. G. 2017. What defines a high-performing health care delivery system: A systematic review. The Joint Commission Journal on Quality and Patient Safety, 43(9), pp.450-459.

Akenroye, T. O. 2012. Factors Influencing Innovation in Healthcare: A conceptual synthesis. The Innovation Journal 17(2).

Andersson, T., Linnéusson, G., Holmén, M. and Kjellsdotter, A. 2023. Nurturing innovative culture in a healthcare organisation–Lessons from a Swedish case study. Journal of Health Organization and Management, 37(9), pp.17-33. https://www.emerald.com/insight/content/doi/10.1108/JHOM-05-2021-0181/full/html

Aryankhesal, A., Sheldon, T. A., Mannion, R. and Mahdipour, S. 2015. The dysfunctional consequences of a performance measurement system: the case of the Iranian national hospital grading programme. Journal of health services research & policy, 20(3), pp.138-145.

Australian Commission on Quality and Safety in Healthcare. 2021. National Safety and Quality in Healthcare Standards. Available at: http://www.achs.org.au/achs-nsqhs-standards (accessed 21 January 2023).

Australian Digital Health Agency. 2018. Digital health strategy. (July): 3–81. Available at: https://ehealthresearch.no/files/documents/Undersider/WHO-Symposium-2019/1-3-Skovgaard-ENG.pdf.

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. 2022a. Australia’s Health 2022. Available at: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports-data/australias-health (accessed 21 December 2022).

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. 2022b. MyHospitals. Available at: https://www.myhospitals.gov.au/hospital/1155H2100/grafton-base-hospital/healthcare-associated-infections (accessed 10 February 2023).

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. 2022c. National Health Performance Authority. Available at: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports-data/australias-health-performance (accessed 10 February 2023).

Australian Institute of Health Innovation University of NSW. 2013. Final Report: Performance indicators used internationally to report publicly on healthcare organisations and local health systems.

Baker, G. R. 2011; The roles of leaders in high-performing health care systems. Commission on Leadership and Management in the NHS. The Kings Fund. Available at: http://www.kingsfund.org.uk/publications/articles/roles-leaders-high-performing-health-care-systems.

Baker, R. G. and Axler, R. 2015. Creating A High Performing Healthcare System for Ontario: Evidence Supporting Strategic Changes in Ontario Health System Reconfiguration.

Balding, C. and Jones, C. n.d. No Harm Done Podcast. http://noharmdonepodcast.com/

Balas, E. A. and Chapman, W. W. 2018. Road map for diffusion of innovation in health care. Health Affairs. Project HOPE. DOI: 10.1377/hlthaff.2017.1155.

Board, N. and Watson, D. 2010. Using what we gather — harnessing information for improved care. Medical Journal of Australia, 193(8), p.S93.

Braithwaite, J., Greenfield, D., Westbrook, J., Pawsey, M., Westbrook, M., Gibberd, R., Naylor, J., Nathan, S., Robinson, M., Runciman, B. and Jackson, M. 2010. Health service accreditation as a predictor of clinical and organisational performance: a blinded, random, stratified study. BMJ Quality & Safety, 19(1), pp.14-21.

Braithwaite, J., Ellis, L. A., Churruca, K. and Long, J. C. 2018. The goldilocks effect: the rhythms and pace of hospital life. BMC health services research, 18, pp.1-5.

Bureau of Health Information. 2022. Measurement Matters. https://www.bhi.nsw.gov.au/BHI_reports/measurement_matters (accessed 10 February 2023).

Canaway, R., Bismark, M., Dunt, D. and Kelaher, M. 2017a. Perceived barriers to effective implementation of public reporting of hospital performance data in Australia: a qualitative study. BMC Health Services Research, 17, pp.1-12.

Crossan, M. M. and Apaydin, M. 2010. A multi‐dimensional framework of organizational innovation: A systematic review of the literature. Journal of management studies, 47(6), pp.1154-1191.

Damanpour, F. 1996. Organizational Complexity and Innovation: Developing and Testing Multiple Contingency Models. Management Science 42(5): 693–716. DOI: 10.1287/mnsc.42.5.693.

Dias, C, and Escoval, A. 2013. Improvement of hospital performance through innovation: toward the value of hospital care. The health care manager 32(2): 129–40. DOI: 10.1097/HCM.0b013e31828ef60a.

Dobni, C. B. 2008. Measuring innovation culture in organizations: The development of a generalized innovation culture construct using exploratory factor analysis. European Journal of Innovation Management 11(4): 539–559. DOI: 10.1108/14601060810911156.

Dobni, C. B., Klassen, M. and Nelson, W. T. 2015. Innovation strategy in the US: top executives offer their views. Journal of Business Strategy, 36(1), pp.3-13.

Phillips, N. 2013. Organizing Innovation. In: Dodgson, Mark, David M. Gann, and Nelson Phillips, eds. The Oxford handbook of innovation management. Oxford University Press.

Fleuren, M., Wiefferink, K. and Paulussen, T. 2004. Determinants of innovation within health care organizations: literature review and Delphi study. International journal for quality in health care, 16(2), pp.107-123.

Foster, T. C., Johnson, J. K., Nelson, E. C. and Batalden, P. B. 2007. Using a Malcolm Baldrige framework to understand high-performing clinical microsystems. BMJ Quality & Safety, 16(5), pp.334-341.

Freeman, T. 2002. Using performance indicators to improve health care quality in the public sector: a review of the literature. Health Services Management Research, 15(2), pp.126-137.

Garman, A. N., McAlearney, A. S., Harrison, M. I., Song, P. H. and McHugh, M. 2011. High-performance work systems in health care management, part 1: development of an evidence-informed model. Health care management review, 36(3), pp.201-213.

Greenfield, D. and Braithwaite, J. 2008. Health sector accreditation research: a systematic review. International Journal for Quality in Health Care 20(3): 172–183. DOI: 10.1093/intqhc/mzn005.

Greenfield, D., Hinchcliff, R., Banks, M., Mumford, V., Hogden, A., Debono, D., Pawsey, M., Westbrook, J. and Braithwaite, J. 2015. Analysing ‘big picture’ policy reform mechanisms: the Australian health service safety and quality accreditation scheme. Health Expectations, 18(6), pp.3110-3122.

Greenfield, D., Lawrence, S. A., Kellner, A., Townsend, K. and Wilkinson, A. 2019. Health service accreditation stimulating change in clinical care and human resource management processes: a study of 311 Australian hospitals. Health Policy, 123(7), pp.661-665.

Greenhalgh, T. and Abimbola, S. 2019. The NASSS Framework A Synthesis of Multiple Theories of Technology Implementation. Studies in Health Technology and Informatics 263. IOS Press: 193–204. DOI: 10.3233/SHTI190123.

Greenhalgh, T., Hinder, S., Stramer, K., Bratan, T. and Russell, J. 2010. Adoption, non-adoption, and abandonment of a personal electronic health record: case study of HealthSpace. Bmj, 341.

Greenhalgh, T., Robert, G., Macfarlane, F., Bate, P. and Kyriakidou, O. 2004. Diffusion of innovations in service organizations: systematic review and recommendations. The milbank quarterly, 82(4), pp.581-629.

Greenhalgh, T., Robert, G., Bate, P., Macfarlane, F. and Kyriakidou, O., 2008. Diffusion of innovations in health service organisations: A systematic literature review.

Greenhalgh, T. and Papoutsi, C. 2019. Spreading and scaling up innovation and improvement. Bmj, 365.

Greenhalgh, T., Wherton, J., Papoutsi, C., Lynch, J., Hughes, G., Hinder, S., Fahy, N., Procter, R. and Shaw, S. 2017. Beyond adoption: a new framework for theorizing and evaluating nonadoption, abandonment, and challenges to the scale-up, spread, and sustainability of health and care technologies. Journal of medical Internet research, 19(11), p.e8775.

Hage, E., Roo, J. P., van Offenbeek, M. A. and Boonstra, A. 2013. Implementation factors and their effect on e-Health service adoption in rural communities: a systematic literature review. BMC Health Services Research, 13(1), pp.1-16.

Hanson R. M. 2011. Good health information – an asset not a burden!. Australian Health Review 35, 9-13. https://doi.org/10.1071/AH09865

Harrison, M. I., Paez, K., Carman, K. L., Stephens, J., Smeeding, L., Devers, K. J. and Garfinkel, S. 2016. Effects of organizational context on Lean implementation in five hospital systems. Health care management review, 41(2), pp.127-144.Health Assessment Europe (2023) Health Assessment Europe Accreditation. Available at: https://www.healthassessmenteurope.eu/ (accessed 14 February 2023).

Hibbert, P., Johnston, B., Wiles, L. and Braithwaite, J. 2016. Evidence check: healthcare performance reporting bodies. Evidence check: healthcare performance reporting bodies (apo.org.au)

Johannessen, J. A. 2013. Innovation: a systemic perspective–developing a systemic innovation theory. Kybernetes, 42(8), pp.1195-1217.

Joint Commission. 2023. The Joint Commission: Accreditation. Available at: https://www.jointcommission.org/ (accessed 15 January 2023).

Kaur Kapoor, K., K. Dwivedi, Y. and D. Williams, M. 2014. Innovation adoption attributes: a review and synthesis of research findings. European Journal of Innovation Management, 17(3), pp.327-348.

Körner, M., Wirtz, M.A., Bengel, J. and Göritz, A.S. 2015. Relationship of organizational culture, teamwork and job satisfaction in interprofessional teams. BMC health services research, 15, pp.1-12.

Kringos, D. S., Sunol, R., Wagner, C., Mannion, R., Michel, P., Klazinga, N. S. and Groene, O. 2015. The influence of context on the effectiveness of hospital quality improvement strategies: a review of systematic reviews. BMC health services research, 15(1), pp.1-13.

Lee, D. 2015. The effect of operational innovation and QM practices on organizational performance in the healthcare sector. International Journal of Quality Innovation 1(8). International Journal of Quality Innovation: 1–14. DOI: 10.1186/s40887-015-0008-4.

Leeb, K. 2018. Does health system performance reporting stimulate change? Healthcare Management Forum 31(6): 235–238. DOI: 10.1177/0840470418782515.

Leedham-Green, K., Knight, A. and Reedy, G. B. 2021. Success and limiting factors in health service innovation: a theory-generating mixed methods evaluation of UK projects. BMJ open, 11(5), p.e047943.

Lynch, T. 2015. A Critique of Health System Performance Measurement. International journal of health services: Planning, administration, evaluation 45(4): 743–761. DOI: 10.1177/0020731415585987.

Mafini, C. 2015. Predicting organisational performance through innovation, quality and inter-organisational systems: A public sector perspective. Journal of Applied Business Research (JABR), 31(3), pp.939-952.

Mannion, R. and Braithwaite, J. 2012. Unintended consequences of performance measurement in healthcare: 20 salutary lessons from the English National Health Service. Internal medicine journal, 42(5), pp.569-574.

Philippon, D. J., Marchildon, G. P., Ludlow, K., Boyling, C. and Braithwaite, J. 2018, November. The comparative performance of the Canadian and Australian health systems. In Healthcare Management Forum (Vol. 31, No. 6, pp. 239-244). Sage CA: Los Angeles, CA: Sage Publications.

McAlearney, A. S., Robbins, J., Garman, A. N. and Song, P. H. 2013. Implementing high-performance work practices in healthcare organizations: Qualitative and conceptual evidence. Journal of Healthcare Management, 58(6), pp.446-462.

Moreira, M.R., Gherman, M. and Sousa, P.S. 2017. Does innovation influence the performance of healthcare organizations?. Innovation, 19(3), pp.335-352.

National Health System. 2018. NHS Innovation Accelerator : Understanding how and why the NHS adopts innovation. https://s38114.pcdn.co/wp-content/uploads/NIA-Year3-research-report-digital.pdf

National Institute of Standards and Technology. 2016. Baldrige Performance Excellence Program Are we Making Progress Self-Assessment Tool. Available at: https://www.nist.gov/baldrige/self-assessing/improvement-tools/are-we-making-progress (accessed 1 November 2017).

OECD. 2015. The Innovation Imperative Contributing to Productivity, Growth and Well-Being. Available at: https://www.oecd.org/publications/the-innovation-imperative-9789264239814-en.htm (accessed 21 December 2022).

Øvretveit, J.C., Shekelle, P.G., Dy, S. M., McDonald, K. M., Hempel, S., Pronovost, P., Rubenstein, L., Taylor, S. L., Foy, R. and Wachter, R. M. 2011. How does context affect interventions to improve patient safety? An assessment of evidence from studies of five patient safety practices and proposals for research. BMJ quality & safety, 20(7), pp.604-610.

Palanica, A. and Fossat, Y. 2020. COVID-19 has inspired global healthcare innovation. Canadian Journal of Public Health, 11

Pashaeypoor, S., Ashktorab, T., Rassouli, M. and Alavi-Majd, H. 2016. Predicting the adoption of evidence-based practice using “Roger’s diffusion of innovation model”. Contemporary nurse, 52(1), pp.85-94.

Pronovost, P. 2008. Interventions to decrease catheter-related bloodstream infections in the ICU: The Keystone Intensive Care Unit Project. American Journal of Infection Control 36(10): 1–5. DOI: 10.1016/j.ajic.2008.10.008.

Pronovost, P. J. 2017. High-Performing Health Care Delivery Systems: High Performance Toward What Purpose? Joint Commission Journal on Quality and Patient Safety 43(9). Elsevier Inc.: 448–449. DOI: 10.1016/j.jcjq.2017.06.001.

Pronovost, P. J., Mathews, S. C., Chute, C. G. and Rosen, A. 2017. Creating a purpose‐driven learning and improving health system: The Johns Hopkins Medicine quality and safety experience. Learning Health Systems, 1(1), p.e10018.

Rao, J. and Weintraub, J. 2009. What’s Your Company’s Innovation Quotient. Strategy (1): 1–9.

Rao, J. and Weintraub, J. 2013. How Innovative Is Your Company ’s Culture? MIT Sloan Management Review 54(54315): 29–37.

Rapport, F., Clay‐Williams, R., Churruca, K., Shih, P., Hogden, A. and Braithwaite, J. 2018. The struggle of translating science into action: Foundational concepts of implementation science. Journal of evaluation in clinical practice, 24(1), pp.117-126.

Rizan, C., Phee, J., Boardman, C. and Khera, G. 2017. General surgeon’s antibiotic stewardship: climbing the Rogers diffusion of innovation curve-prospective cohort study. International Journal of Surgery, 40, pp.78-82.

Salter, A. and Alexy, O. 2013. The Nature of Innovation. The Oxford handbook of innovation management (February): 26–49. DOI: 10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199694945.013.034.

Scarbrough, H. and Kyratsis, Y. 2022. From spreading to embedding innovation in health care: Implications for theory and practice. Health care management review 47(3). DOI: 10.1097/HMR.0000000000000323.

Schneider, E. C., Shah, A., Doty, M. M., Tikkanen, R., Fields, K. and Williams, R. II. 2021. Mirror Mirror2021: Reflecting Poorly: Health Care in the US Compared to Other High-Income Countries. New York: The Commonwealth Fund.

Shahian, D. M., Normand, S. L. T., Friedberg, M. W., Hutter, M. M. and Pronovost, P. J. 2016. Rating the raters: the inconsistent quality of health care performance measurement. Annals of surgery, 264(1), pp.36-38.

Shields, J. A. and Jennings, J. L. 2013. Using the Malcolm Baldrige “Are We Making Progress” Survey for Organizational Self‐Assessment and Performance Improvement. Journal for Healthcare Quality, 35(4), pp.5-15.

Shwartz, M., Cohen, A. B., Restuccia, J.D., Ren, Z.J., Labonte, A., Theokary, C., Kang, R. and Horwitt, J. 2011. How well can we identify the high-performing hospital?. Medical Care Research and Review, 68(3), pp.290-310.

Snowdon, A. and Cohen, J. A. 2011. Strengthening health systems through innovation: Lessons learned. Ivey International Centre for Health Innovation.

Srinivasan, U., Ramachandran, D., Quilty, C., Rao, S., Nolan, M. and Jonas, D. 2018. FlyingBlind: Australian Researchers and Digital Health. CMCRC.

Taylor, N., Clay-Williams, R., Hogden, E., Braithwaite, J. and Groene, O. 2015. High performing hospitals: a qualitative systematic review of associated factors and practical strategies for improvement. BMC health services research, 15(1), pp.1-22.

Van Oorschot, J. A., Hofman, E. and Halman, J. I. 2018. A bibliometric review of the innovation adoption literature. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 134, pp.1-21.

West, M. A. and Lyubovnikova, J. 2013. Illusions of team working in health care. Journal of health organization and management, 27(1), pp.134-142.

Witell, L., Snyder, H., Gustafsson, A., Fombelle, P. and Kristensson, P. 2016. Defining service innovation: A review and synthesis. Journal of Business Research, 69(8), pp.2863-2872.

World Health Organization. 2021. Global strategy on digital health 2020-2025. ISBN 978-92-4-002092-4 (electronic version)

Wutzke, S., Benton, M. and Verma, R. 2016. Towards the implementation of large scale innovations in complex health care systems: views of managers and frontline personnel. BMC research notes, 9(1), pp.1-5.