Leadership

Safety and Quality in Healthcare

Safety and Quality in Healthcare

Melanie Murray and Amanda Barnes

Introduction

The terms ‘quality’ and ‘safety’ are frequently used in health and social care. But what does quality mean? In healthcare, quality is defined as “how well healthcare services for individuals and populations achieve desired health outcomes that are consistent with current professional knowledge and standards” (Kelly Vana, Vottero, and Altmiller, 2023, p. 5). Safety, then, is to provide care without harm. Like all things, health, quality and safety are dynamic and should never be considered separate from everyday business but should be ‘business as usual’. In a health and social care system that is ever-evolving, attention to quality and safety is of utmost importance.

Clinical standards and governance systems are central to safety and quality. They are the backbone of effective healthcare and must be in place to ensure quality care, without which expected patient outcomes are threatened. The six domains of a healthcare quality framework were developed by the Institute of Medicine (2001), and assert that care provision should be safe, timely, efficient, equitable, effective, and patient-centred. These were further expanded by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, (2015), and adopted by agencies worldwide, to include “doing the right thing, at the right time, in the right way, to achieve the best possible results” (Kelly Vana, Vottero, and Altmiller, 2023, p. 5). These are reflected in the Australian context through the National Model Clinical Governance Framework (Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Healthcare [ACSQHC], 2017), and in the United Kingdom (UK) through the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (2023) standards and guidelines.

Throughout this chapter, we will discuss the following topics in the hope that it will provide you with a better understanding of these processes and the confidence to manage them in your workplace:

- The concepts of safety and quality in healthcare

- Challenges to quality and safety improvement in healthcare

- Human factors and systems thinking

- Clinical governance

- Standards and accreditation

- Practices within healthcare organisations that support quality and safety in healthcare

Background

The landmark report from the Institute of Medicine, now the National Academy of Medicine, in 2000, To err is human, highlighted the significance of medical errors and adverse events in the United States of America (USA) up until that time. In the 23 years since, healthcare providers globally have been striving to improve patient outcomes by introducing clinical governance and quality improvement strategies. The gaps in quality identified by the Institute of Medicine (2001) include the growing complexity of science and technology, the increase in chronic conditions, and constraints on exploiting the revolution in information technology. This issue does not solely affect the USA. There have been reports of patient safety failures globally. Of note is the Bristol Royal Infirmary Inquiry (Kennedy, 2001), the Queensland Public Hospitals Commission of Inquiry (Davies, 2005), the Special Commission of Inquiry into Acute Care Services in New South Wales Public Hospitals (Garling, 2008), the Mid-Staffordshire National Health Service (NHS) Foundation Trust Public Inquiry (Francis, 2013), the investigation into perinatal outcomes at Djerriwarrh Health Services (Wallace, 2016), and the Royal Commission into Aged Care Quality and Safety (Commonwealth of Australia, 2021). These are a few examples of investigations and reports into poor quality care across the UK and Australia. Whilst considerable improvements have been made worldwide, there is still significant room for improvement.

In response to these global reports of poor patient care and adverse events, the World Health Organization (WHO, 2018) initiated their series of global patient safety challenges. The first challenge of ‘Clean Care is Safer Care’ put handwashing in the spotlight, and is where the Australian National Hand Hygiene initiative (ACSQHC, 2023) began. The WHO’s (2018) second challenge, ‘Safe Surgery Saves Lives’, saw the surgical safety checklist introduced into operating rooms as the ‘time out’ procedure; and the third and current challenge is ‘Medication Without Harm’ aiming to decrease medication errors globally by 50% over five years. These challenges can be viewed as large-scale quality improvement activities aiming to decrease preventable adverse events globally (WHO, 2018).

In 2006, the Council of Australian Governments made a commitment to improve quality of health services, resulting in the establishment in 2011 of the Australian Commission on Quality and Safety in Healthcare (ACSQHC, 2023) (the Commission). The Commission is the primary organisation charged with national improvements for healthcare in Australia. Many changes have been instigated since the Commission was established, including the implementation of the National Safety and Quality Health Service Standards (NSQHSS) (ACSQHC, 2017), the National Inpatient Medication Chart (ACSQHC, 2023), and the Early Warning System observation charts (ACSQHC, 2012), to name a few (ACSQHC, 2023). These changes have proved effective through the demonstration of improved patient outcomes nationally. Evidence of this can be seen in the decrease in potentially preventable healthcare-acquired complications, or adverse events, following the guidance offered in NSQHSS’ Preventing and Controlling Infections standard. We have seen a decrease in Australia, from 10% in 2014/15 to approximately 2% of all hospital separations in Australia in 2021 (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2022). However, the health system is reliant on human beings and errors and adverse events are going to occur. Clinical governance and quality improvement (QI) systems therefore must be robust enough to manage the challenge.

What is clinical governance?

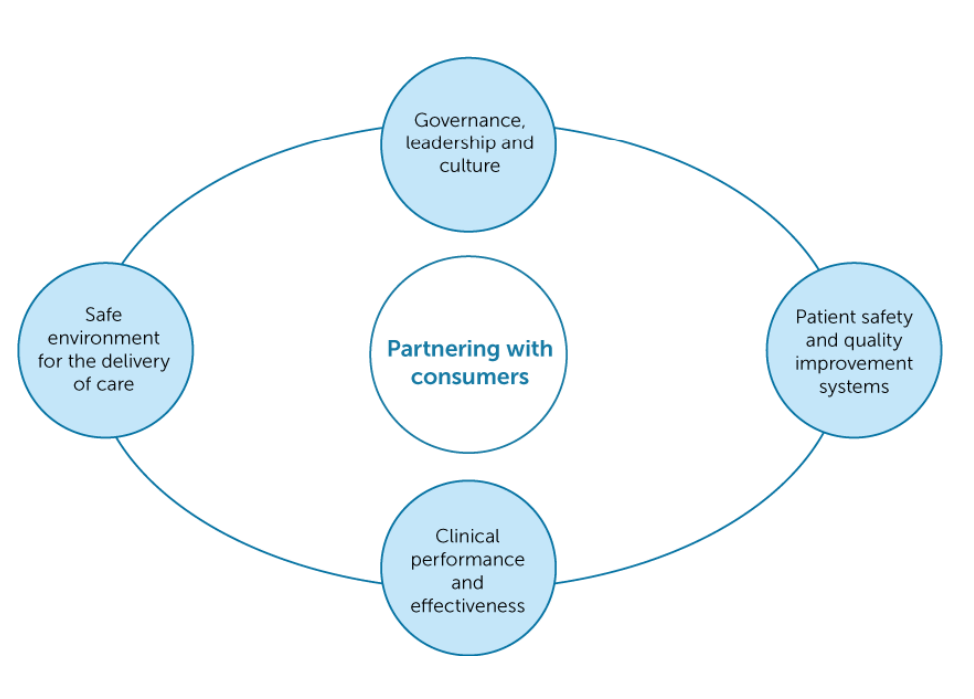

According to the ACSQHC (2017, p. iii), clinical governance “…ensures that everyone – from frontline clinicians to managers and members of governing bodies, such as boards – is accountable to patients and the community for assuring the delivery of health services that are safe, effective, integrated, high quality and continuously improving”. Clinical governance has been introduced into healthcare worldwide to address the extensive variations in standards and quality of care. Many frameworks are available, and the Commission published the National Model Clinical Governance Framework (the Framework) in 2017, supporting the NSQHS Clinical Governance Standard (ACSQHC, 2017). While being an individual standard, clinical governance is also embedded throughout all eight NSQHS standards as action item one. This specifically addresses the minimum quality standards expected in all Australian healthcare organisations concerning governance, leadership and culture, patient safety and quality systems, clinical performance and effectiveness, and a safe environment for the delivery of care (ACSQHC, 2021, Standard 1). The figure below illustrates Australia’s clinical governance framework.

The many incidents of poor care around the world can be linked to a lack of clinical governance. All organisations require some form of corporate governance encompassing all aspects, specifically risk, finance, and other areas such as human resources (HR), and information technology (IT). Frameworks may vary; however, the consumer is central to most.

As with any framework, there are often supports and challenges. Examples of supporting principles underpinning effective clinical governance are:

- vision and values;

- clear organisation and committee structures;

- cultural and professional safety;

- recruitment and retention strategy;

- induction and orientation programs, performance reviews, goal setting, and performance management; and

- mandatory training and clinical competency framework.

Challenges of implementing a clinical governance system include the following:

- knowledge and understanding of the concept,

- unclear organisation expectations and outcomes,

- lack of infrastructure to support the organisation’s vision,

- not having the right people to deliver on the vision,

- budget,

- tools,

- time,

- accountability, and

- gradients of hierarchy that are often the cause of conflict.

Clinical Governance Vignette

The landscape of health is complex, and often described as being a beast! It is in a perpetual state of change and requires an effective governance framework to prevent the whipping up of a ‘perfect storm’ that is likely to result in the delivery of sub-optimal care, harm to a patient or staff member, or increased reputational risk for the business. A plethora of literature evidences how a structured clinical governance program can prevent this from happening.

Reflection

If you are unsure and find yourself doing a sneaky Google search, you can be sure you are not the only one! Ask anyone in your organisation what is clinical governance, how to ‘do it’, and what the expectation or intended outcomes are, and you will either get the tumble weeds of silence or an abundance of differing perceptions and descriptions of the concept. Either way, this is not going to help you embed the principles and optimise the delivery of safe and effective patient-centred care.

Ask the question… it will provide you with insight into the general understanding of your team.

Now that you have oversight of your team’s understanding, you have a starting point and can begin to build your governance framework. Find a definition that you understand and can relate to, after all, you are the one that will need to explain it and make it real.

Beware…there are a LOT of definitions, so take the time to do your research. Like all areas of health, clinical governance has its own suite of jargon that you would be wise to investigate and understand; clinical governance is indeed one of those terms! ‘Pillars’ is another one, and it means nothing to those not indoctrinated into the world of quality management. Early literature describes frameworks with four pillars of governance(ACSQHC, 2017); however, as health systems have grown and services become more complex, the number of pillars of clinical governance has expanded to six or seven. Pillars are essentially ‘buckets’ in which actions, activities, systems, and processes can be grouped so they create an outline for your clinical governance framework and include (but are not limited to):

- Policy – A platform where your policies and procedures are stored. This should include visibility of version control and review dates and should be easily accessible by all staff.

- Risk management – An incident reporting system that includes an incident investigation model (Root Cause Analysis [RCA], Failure Modes and Effects [FMEA])

- Consumer engagement – Clear processes for allowing consumers to provide feedback, compliments, and complaints.

- Education and training – A mandatory training program outlining what programs must be completed, the frequency, and mode of delivery, including scope of practice and clinical competency requirements.

- Monitoring systems – An audit framework outlining what should be measured/monitored, the frequency, and outcomes. This should include both clinical and non-clinical areas.

- Clinical effectiveness – This incorporates recruitment practices, retention strategies, induction, orientation, professional development, performance review, and performance management.

Activity

Action…Take a look at your organisation and consider the list above.

So, what comes next? Now you know the key processes that create a clinical governance framework, it is essential that you learn and share how each process is dependent and inextricably linked to each other.

PRIORITY ACTION

Failure to do this effectively will result in the systems being siloed, your team will become disengaged from the vision, and there will be minimal safety and quality improvement in your organisation.

Clinical governance is only as effective as the effort and commitment put in to achieve it. Spend the time to find the right interested people who have passion and are keen to learn, as these are your champions and will fight for your vision. Make the time to hold workshops, let everyone share their ideas, and decide how all the pieces fit together. Shared learning creates team-ship, builds trust, and develops a common goal, getting everyone on the same page.

Key Takeaways

Key learning…Be sure to include the multidisciplinary team in the development and implementation of your program. Taking them on the journey will promote organisational accountability and will be key to your success.

Design your committee structure to mirror your clinical governance framework, review your meeting attendees to ensure you have appropriate representation, and make your meetings matter by using structured agendas, minutes and clear actions, owners, and timeframes.

And finally, communicate, communicate, communicate!!!

Quality Improvement

Quality improvement (QI) is central to the success of any clinical governance program, and a well-executed program offers structure, accountability, and oversight of progress. In recent years, the emphasis on QI in healthcare has become a major focus, with the Commission publishing the National Clinical Governance Framework at the same time as detailing what an effective quality improvement system looks like under Action 1.8 of the NSQHSS Version 2 (ACSQHC, 2017, updated 2021).

However, QI is one of the most challenging principles to implement consistently, because it has its fingers in the pies of all the other pillars of safety and quality systems. Additionally, despite QI being recognised as the key to advancing quality processes, we quite often find that QI barely gets a mention in textbooks, with a measly offering of a couple of pages outlining only the high-level concept. Not at all helpful! So, what is the potential of QI?

Well, we already know the systems that can help us identify opportunities for making improvements, audit, staff suggestions, complaints, and incidents, but QI is so much bigger and can be so much better. Quality improvement practices give us an opening to collaborate with our people, we can use it to encourage professional development, promote trust through the sharing or delegation of responsibility, and when your people are recognised for their input, no matter how big or small, their commitment will grow. QI is the perfect opportunity for you to invest in your people, show your respect for them, celebrate the successes together, and watch your organisation embrace change.

A method used to monitor the quality of Australian health services is regular accreditation surveys. Accreditation to the NSQHSS is a national approach to set a minimum expected quality, safety, and care standard throughout all healthcare facilities (ACSQHC, 2017). Developing a strong safety culture and achieving successful accreditation outcomes requires commitment from all levels within the organisation, from the executive to the bedside. This principle underpins the success of any clinical governance framework, assuring best and consistent practice across the continuum, including risk management and quality improvement.

Although QI is essential to improving patient safety and outcomes, as with any change or QI activity, there will be barriers and facilitators. Some barriers highlighted in the literature include lack of protected time to undertake QI, healthcare workers (primarily nursing staff) prioritising other duties, lack of leadership support, lack of QI champions, and ineffective or poor communication (Zoutman and Ford, 2017).

To support ongoing quality care, the New South Wales Health Clinical Excellence Commission put together the following resource that explains the practical application of the six domains of healthcare quality for improving practice.

The Six Dimensions of Healthcare Quality was created by Clinical Excellence Commission and is available from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=I8Y962VTiBY

| Quality Improvement Vignette

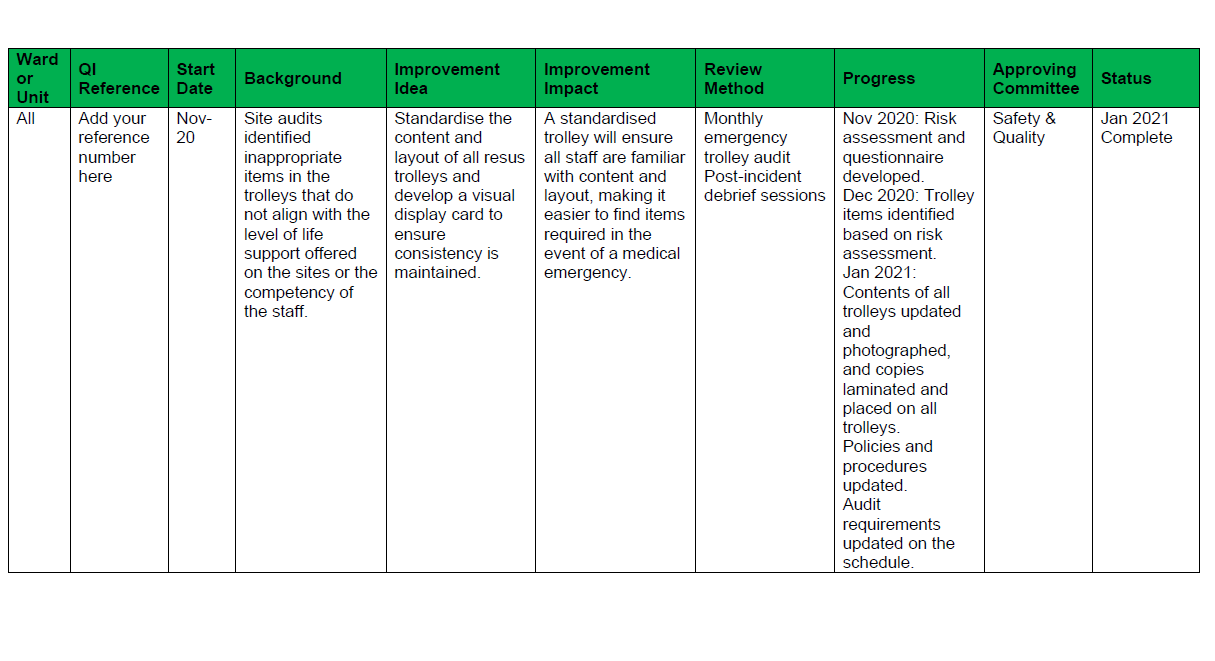

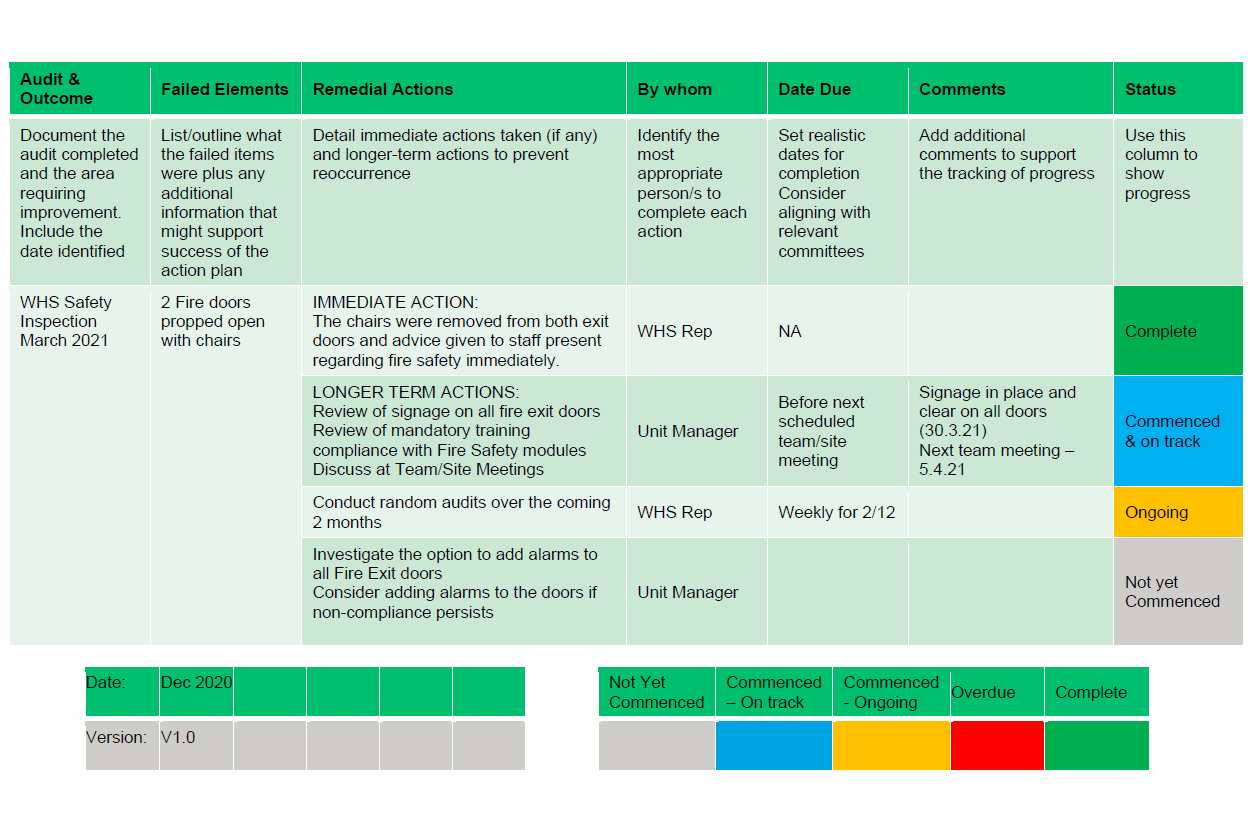

Tips to make QI successful In health organisations, there is generally a person or department dedicated to safety and quality, and they will have access to these systems. The risk here is that the scope and potential of improvement ideas and activities are narrowed because the wider organisation does not have visibility or access and are unlikely to be aware of the issues, and are therefore unintentionally excluded from the opportunity to innovate. You can change this by being transparent with the information, finding a way to share it, and making it accessible. Suggestion: Have a ‘Challenges’ page on your Intranet, grouping issues together and inviting people to share their ideas and solutions. Use your strongest resource (the people) and make them the drivers. Once the improvement idea has been identified and you have a group of super enthusiastic champions, you need to ensure you do not lose track and momentum of the project. Like we said, QI activities are happening constantly, with differing levels of priority and urgency, and often involving more than one area of the business or the clinical governance framework. Each QI activity should have an action plan (see the example below). The plan should clearly identify who is responsible for each action, when the action is due to be completed, and how and when the success of the action will be measured. You then need a register collating this information for all your active QI activities, which becomes your platform for oversight, ensuring you have visibility of accountable persons, deliverables, and timeframes. Each action plan owner must be responsible for updating the register (usually monthly) and this is then included in your Safety and Quality Committee for review and tracking. Do not underestimate the power of QI. An example register is provided below. Reflection Ask yourself, what is the point of having, using, and monitoring quality systems if you are not going to invest in the process of remedying the suboptimal findings?

|

Theories and Models

There is no one way to approach quality and safety. Here, we will briefly discuss some different theories and models that may underpin your organisations approach to safety, risk, and QI.

Safety-I to Safety-II

Smith and Plunkett (2019) proposed that the approach to safety, and subsequently, incident and accident investigation, has moved into a third ‘age’. The first two ages being the “age of technology” and the “age of human factors”, with the third being “age of safety management” (Smith and Plunkett, 2019, p. 508). In 2015, Hollnagel et al. (2015) published a white paper describing the perspectives of safety and the shift from ‘safety-I’ to ‘safety-II’. The safety-II approach to investigation is that the focus should be on “how things usually go right” (p. 4), rather than the safety-I philosophy of safety being “…a state whereas few things as possible go wrong” (Hollnagel et al., 2015, p. 3). While we are advancing from the ‘age of human factors’, consideration of human factors during development and optimisation of systems supports the safety-II approach. Humans are fallible but flexible and can adjust where necessary to avoid an incident, whereas fixed systems are often not flexible, and errors will inevitably occur.

Incident investigation – Root Cause Analysis

Many organisations undertake incident investigations by way of a root cause analysis (RCA), a somewhat linear approach seeking a cause amongst the many layers of an organisation. Despite its linearity, this model can be very effective if used appropriately. The following video developed by ThinkReliability© (Galley, 2018) provides a simple overview that demonstrates how the cause-and-effect tools, the 5 why’s, and Ishikawa (fishbone) diagram can be used at various depths to seek the underlying systems issues that lead to incident occurrences.

What is Root Cause Analysis was created by CauseMapping and is available from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sFQFfrYjtPU

Reflection

Systems Thinking

Industries outside of health, such as the safety-critical aviation industry, continually search for new ways of assessing incidents to ensure maximum levels of safety. However, healthcare often lags. Systems thinking and the systems approach to safety and investigations are more holistic approaches that acknowledge the complexities of a system such as health (McNab et al., 2020). However, the systems approach needs to be supported by the whole organisation to ensure a culture of safety and effective leadership is essential. Engagement of all healthcare team members is necessary for successful outcomes and, more importantly, overall safety culture. With the significant advancement and integration of technology into healthcare, quality and safety issues have also been associated with this (McNab et al., 2020). As such, a multidisciplinary approach, including Information Technology (IT), is required (Bates and Singh, 2018). As you saw in the RCA video, getting to the ‘root/s’ of the problem requires us to look at the systems as a whole and not stop at the individual/s who made the error.

Plan, Do, Study, Act (PDSA)

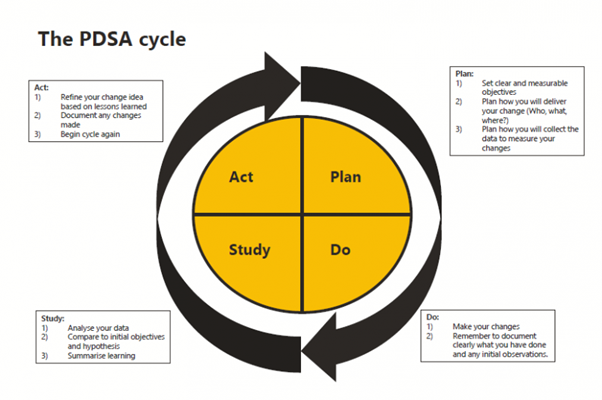

A QI activity needs a structured approach. The Plan, Do, Study Act (PDSA) cycle is the common model used in healthcare, initially developed by Shewhart around 1936, and further refined by Deming throughout the 1990’s, with the model we know today described in 1996. The figure below illustrates the cycle and provides a brief outline of what occurs in each stage. You may see some similar features from this model in the nursing process of assess, diagnose, plan, implement, evaluate (ADPIE) (Mason and Attree, 1997), or the Clinical Reasoning Cycle (consider the situation and collect cues, process the information, plan, implement, evaluate, and reflect) (Levett-Jones, 2017). It would be rare that you follow the cycle just once. QI cycles, as with the nursing and clinical reasoning cycles and continue iteratively as situations evolve.

Reflection

Human Factors

Human factors are about understanding human behaviour and performance to recognise the capabilities and limitations of working with people. This is important in healthcare, as when we understand these behaviours, capabilities, and limitations, we can better design systems to consider these, and thus reduce the likelihood of errors (Lock, 2018). In 1993, Gordon Dupont, an aircraft maintenance engineer and accident investigator, sought to better understand the commonalities among the accidents he was investigating (Dupont-Adam, 2021). A retrospective review of thousands of maintenance error records found 12 ‘preconditions’ associated with these reports. These became known as the ‘dirty dozen’, and have been adopted worldwide to help develop systems to mitigate these issues. The dirty dozen are:

- lack of communication,

- complacency,

- distraction,

- stress,

- lack of teamwork,

- lack of resources,

- pressure,

- lack of assertiveness,

- lack of knowledge,

- norms,

- fatigue,

- lack of awareness.

These 12 factors have been shared by the Clinical Excellence Commission (2021) in an effort to provide strategies to address some of the issues that have arisen in health systems during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Reflection

| Risk Management Vignette

Managing risk is about identifying and reducing harmful or adverse events in a health service’s clinical and non-clinical environments, investigating incidents that have occurred, and progressing remedial and improvement activities to prevent repetition of the event. Risk management is one ‘pillar’ of the overall governance framework, and as an individual component, is a much less complicated concept to understand, and therefore in theory, should be easier to apply. Additionally, the processes and workflows applied across the continuum of risk management are linear and often prescriptive in direction and application. Reflection Why is there an abundance of literature evidencing significant variance in the levels of compliance and success in managing clinical risk? How do established healthcare organisations become the focus of public inquiries, such as Bacchus Marsh/Djerriwarrh Health Service in Victoria (2015), or the Perth Children’s Hospital inquiry in 2021 following the death of Aishwarya Aswath in 2021? You can read more about these inquiries here: Note that these incidents are at the extreme end of the incident spectrum, but the system failings identified as contributing to these catastrophic outcomes did not develop overnight and have been proven to be largely preventable. As leaders, we are responsible for understanding why our current incident management system may be at risk of failing and how we can prevent this from occurring. Let us explore some of the barriers to a successful system. Identifying if any of them apply to your organisation, as remedying them may well be the key to your future success. First, risk management relies upon a robust risk register – without this, there is no order to, oversight of, or accountability for the safety of your business. What is a Risk Register? Simple…it is a register that collates the risks in your organisation, allowing clear identification of them, and strategies to be put in place to prevent eventuation of these risks. Identified risks tend to fall into standard categories, such as financial, reputation, environmental, business continuity and clinical, and the register should be monitored regularly by the committee in your organisation with the highest level of governance. Risks are identified through many sources, the most predominant being the Incident Management System (IMS), and in many organisations, this is where management and prevention of risk begin to fail. Failure to report Be honest… following an incident have you ever found yourself thinking “why on earth did they do that”? We all have, haven’t we? The incident may not have been a high level, severe, or significant event, but I imagine everyone one of you reading this text has at least one example of an incident that invoked feelings of disbelief or embarrassment, fear, or mistrust, and some that make us want to protect ourselves because of the fear of blame. Previous experience or perceived outcomes, your own or anecdotal, may result in the non-reporting of incidents. How do we make sure there is integrity in a ‘no-blame’ approach? We look at the system, not the person. This is much easier said than done, and of course there will be times when behaviour and performance come into the equation. However, starting your investigation by looking at the process, working through it step by step, and identifying the gaps will demonstrate commitment to a blameless process. Ineffective investigation Root cause analysis (RCA) is the process most often used in the healthcare industry; however, several methods of investigation come under this umbrella, and you must determine which one fits your needs and the incident being investigated. Be consistent with the approach you use (5 Whys, Ishikawa [Fishbone], Failure Modes and Effectiveness Analysis [FMEA]), allocate a lead for the process and make sure your leadership team is trained in the principles of RCA. Once you have found the style that fits – stick with it – you will get better outcomes as confidence and competence develops. Get the right people in the room. This can be uncomfortable. The fear associated with RCA is historical and deeply rooted. Medical or administrative hierarchy can be challenging, but you must do this to ensure integrity in the process and improvement in clinical safety. If this process is ineffective, your outcomes will be suboptimal, recommendations will likely acquiesce to the loudest voice or most senior representative present, there will be limited change. and therefore no improvement. Do not be ineffective. Trust the process and challenge the status quo! No oversight of outcomes Your staff will lose trust and faith in you and your IMS if they do not receive feedback on the incidents they report. Make time, either at your team meeting or individually depending on the incident type, recognise the time taken to complete the report, and include them in the journey of investigation and development of improvement recommendations. This may seem like additional work for you, but it will pay off. Even high acuity incidents should be discussed. Of course, you should apply censorship to maintain confidentiality, but use incidents and investigations as opportunities to learn. Providing real examples with tangible outcomes will support change in your organisation, including providing the reasons and rationale for the change. We have identified fear as a common theme throughout this piece. Reflection Ask yourself, is the fear associated with incident management yours or your team members? What is this fear driven by? And how can we turn that fear into a driver for change? Lead with bravery |

When investigating incidents, it is important to take into consideration any influencing human factors such as those in the list. It is extremely rare that anyone purposely acts to cause harm. However, there are often a series of issues in the lead up to a particular event where human factors plays a role. Poor communication, or the lack of, is often a significant factor that can result patient death. Many coroner’s reports outline communication failures at critical points throughout a patient’s journey that significantly contributed to a patient’s death. While lack of communication is just one of the ‘dirty dozen’, many of the other 11 can each effect how someone communicates. Many can also influence the safety culture of the environment, particularly where complacency is accepted. These factors also need to be considered in the overall risk management of an organisation.

Action Plan Example

Key Takeaways

Failure to understand, commit to, teach, and embed the principles of clinical governance will result in catastrophic outcomes for patients. Just as we have seen from the inquiries referred to earlier in the chapter, this cannot be disputed. But the negative impacts do not stop there. What about our employees, our colleagues, ourselves? We are sure you have all heard the saying “people don’t leave bad jobs; they leave bad leaders”. Bad leadership goes hand in hand with poor governance. If we recognise and accept this, then we can use this to our advantage and use the clinical governance systems to empower our people to be the best version of themselves.

Through inclusive practice and communication, we can provide variety in the roles undertaken, and can expand the scope of work and provide professional development, in turn creating interest and motivation. Recognition of interest and involvement demonstrates investment and respect, inspires confidence, and supports role and organisational succession planning. Retention stops being an issue and reputation recognises you as the healthcare provider of choice.

Version 2 of the NSQHSS has significantly increased its focus on culture, because the power of kindness, having integrity, and truly believing in and adhering to your organisation’s values is how to build your organisation’s framework of safety (ACSQHC, 2017).

Genuinely caring for your people, hearing them, and leading them with respect is the way to deliver great governance and patient care, and achieve amazing staff satisfaction.

References

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. 2015. Six domains of Health Care Quality. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. https://www.ahrq.gov/talkingquality/measures/six-domains.html

Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care. 2012. Adult Deterioration Detection System (ADDS) chart with blood pressure table. Available at: https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/publications-and-resources/resource-library/adult-deterioration-detection-system-adds-chart-blood-pressure-table

Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care. 2017. National Model Clinical Governance Framework. Available at: https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/publications-and-resources/resource-library/national-model-clinical-governance-framework

Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care. 2017 (updated May 2021). The NSQHS Standards. Available at: https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/standards/nsqhs-standards

Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care. 2023. About Us. Available at: https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/about-us

Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care. 2023. National Hand Hygiene Initiative. Available at: https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/our-work/infection-prevention-and-control/national-hand-hygiene-initiative#implementation-of-the-national-hand-hygiene-initiative

Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care. 2023. Medication Charts. Available at: https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/our-work/medication-safety/medication-charts

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. 2022. Hospital Safety and Quality. https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports-data/myhospitals/themes/hospital-safety-and-quality

Bates, D. W. and Singh, H. 2018. Two decades since To Err is Human: An assessment of progress and emerging priorities in patient safety, Health Affairs, 37(11), pp. 1736–1743. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2018.0738

Clinical Excellence Commission. 2021. Human Factors Principles, New South Wales Government. Available at: https://search.cec.health.nsw.gov.au/s/redirect?collection=nsw_health_cec&url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.cec.health.nsw.gov.au%2F__data%2Fassets%2Fpdf_file%2F0008%2F580697%2FHuman-Factors-COVID19-and-the-Dirty-Dozen.pdf&auth=csDt2SRcHQn4lFPcXaHZpg&profile=_default&rank=1&query=dirty+dozen

Commonwealth of Australia. 2021. Royal Commission into Aged Care Quality and Safety. Commonwealth of Australia. Available at: https://agedcare.royalcommission.gov.au/sites/default/files/2021-03/final-report-volume-1_0.pdf

Davies, G. 2005. Queensland Public Hospitals Commission of Inquiry. rep. Queensland Government. Available at: http://www.qphci.qld.gov.au/

Dupont-Adam, R. 2021. Let’s Talk Human Factors – Origin of Dirty Dozen. SMS Pro Aviation Safety Software Blog 4 Airlines & Airports. Available at: https://aviationsafetyblog.asms-pro.com/blog/lets-talk-human-factors-origin-of-dirty-dozen (Accessed: December 2022).

Francis, R. 2013. Report of the Mid Staffordshire NHS Foundation Trust Public Inquiry. London: Crown.

Galley, M. 2018 What is Root Cause Analysis. ThinkReliability. Available at: https://youtu.be/sFQFfrYjtPU

Garling, P. 2008. Garling report – Final report of the special commission of inquiry into acute care services in NSW Public Hospitals, Premier & Cabinet. Available at: https://www.dpc.nsw.gov.au/publications/special-commissions-of-inquiry/special-commission-of-inquiry-into-acute-care-services-in-new-south-wales-public-hospitals/

Hollnagel E., Wears R. L. and Braithwaite J. 2015. From Safety-I to Safety-II: A White Paper. TheResilient Health Care Net: Published simultaneously by the University of Southern Denmark, University of Florida, USA, and Macquarie University, Australia. https://www.england.nhs.uk/signuptosafety/wp-content/uploads/sites/16/2015/10/safety-1-safety-2-whte-papr.pdf

Institute of Medicine. 2001. Crossing the quality chasm: A new health system for the 21st Century. National Academies Press.

Kelly Vana, P., Vottero, B. A. and Altmiller, G. 2023, Quality and Safety Education for Nurses: Core Competencies for Nursing Leadership and Care Management. 3rd edn. Springer Publishing.

Kennedy, I. 2001. Learning from Bristol: the report of the public inquiry into children’s heart surgery at the Bristol Royal Infirmary 1984 -1995. rep. Secretary of State for Health. Available at: https://www.bristol-inquiry.org.uk/final_report/rpt_print.htm

Kohn, L. T., Corrigan, J. M. and Donaldson, M. S. (eds)., 2000. To err is human: Building a safer health system. National Academy Press.

Levett-Jones, T. 2017. Clinical reasoning: Learning to think like a nurse. 2nd edn. Pearson Australia.

Lock, A. 2018. Nexus: Human Performance Training – connecting healthcare and aviation. 2nd edn. Government of Western Australia East Metropolitan Health Service.

McNab, D., McKay, J., Shorrock, S., Luty, S. and Bowie, P. 2020. Development and application of ‘systems thinking’ principles for quality improvement. BMJ Open Quality, 9,e000714. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjoq-2019-000714

Mason, G. M. C. and Attree, M. 1997. The relationship between research and the nursing process in clinical practice. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 26: 1045-1049. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2648.1997.00472.x

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2023. Home. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/

Smith, A. F. and Plunkett, E. 2019. People, systems and safety: Resilience and excellence in healthcare practice. Anaesthesia, 74(4), pp. 508–517. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/anae.14519

Strategy Unit. 2018. Deming’s PDSA cycle NHS choices. NHS. Available at: https://www.strategyunitwm.nhs.uk/publications/pdsa-cycles

Wallace, E. M. 2016. The investigation into perinatal outcomes at Djerriwarrh Health Services. Department of Health and Human Services.

World Health Organization. 2018. Patient safety. http://www.who.int/patientsafety/en/

Zoutman, D. E. and Ford, B. D. 2017 Quality Improvement in hospitals: Barriers and facilitators. International Journal of Health Care Quality Assurance, 30(1), pp. 16–24. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1108/ijhcqa-12-2015-0144