People in Health and Social Care

Performance Management and Training and Development of the Health Workforce

Richard Olley

Introduction

Performance management is an ongoing communication process between a leader and team members to establish a shared awareness of the organisation’s expectations about what is to be achieved at individual employee or team levels (Galeazzo et al., 2021). It aligns the organisational goals with employees’ agreed measures, skills, competency requirements, development plans, and results delivery. Contemporary emphasis is moving from performance assessment in terms of efficiency, resulting in improvement toward what Noto and Noto (2018) asserted is the achievement of broader goals and outcomes, and an increased focus on performance management governance. The focus has shifted towards identifying learning, training and development needs, and other strategies to facilitate achieving an individual’s personal goals and couple these with the overall business strategy, thus creating a high-performance workforce.

Performance management is about what team members have not achieved and what they can achieve linked to organisational goals and strategies (Mukarramah et al., 2017 ). To this end, performance management should not be a term for managing poor performance. It is contended here that performance management is more about the self-regulation of behaviour by team members, and that individuals may actively participate in planning their performance goals by monitoring their progress toward their achievements (Presbitero and Teng-Calleja, 2019). Presbitero and Teng-Calleja (2019) demonstrated that proactive feedback-seeking behaviour, or team members actively seeking feedback on performance when empowered to be proactive and self-regulate, mediates the relationship between the team member’s personality and their ability to plan their performance.

In concert with performance management is the necessity of training and development of team members, so that they have the skills, knowledge, and abilities to fulfil the role for which they are employed (Rodriguez and Waters, 2017). Training is critical for the growth and development of employees in any organisation. It is vital in the healthcare and social care industries due to the need for highly reliable workforce practices and procedures due to safety. Undoubtedly, having robust and relevant staff training and development programs for the health and social care systems is a critical strategy for retaining talent. This chapter also examines training and development needs and evaluates training needs analysis.

Performance Management in Health and Social Care Workforces

A Brief History of Performance Management

Modern performance management became the topic of discussion and a human resource management practice approximately 60 years ago.

Watch the following video, The History of Performance Management, made by the Bersin Academy (2020), which shows the progression of performance management over time and sets the scene for this chapter section.

This video shows older and contemporary approaches to performance management, and what occurs today has come from quite ancient beginnings. We have moved from setting output targets to being more focussed on outcomes, objective assessment, and self-regulation from team members. Increasingly, the performance review focuses on what learning, training, and development is required and how individual employees and teams could further improve their performance and outcomes for their efforts.

The history of performance management, from the Josh Bersin Academy. Source: Bersin Academy, (2020) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YqdR_ejViMI

Initially, performance management was a source of income justification and was used to determine an employee’s future remuneration based on performance . In those early years, organisations implemented various performance management techniques for specific efficiency and productivity outcomes (Justin and Joy, 2022 ). In practice, this worked well for certain employees solely driven by financial rewards. However, where employees are driven by the learning and development of their skills, it fails miserably (Justin and Joy, 2022).

In the late 1980s, the gap between the justification of pay and the development of skills and knowledge became a huge problem in performance management. It came with the realisation that a more comprehensive approach to managing and rewarding performance is required. It was further developed in the United Kingdom and the United States much earlier than in Australia. More recently, managing people, and therefore their performance has become more formalised and specialised. In contemporary organisations, replacing older performance appraisal methods with aims for a more extensive and comprehensive management process is complete with those that concentrate more on developmental strategies designed to improve the technical and also the soft skills of employees (Anna, 2016). The main drivers of the change in approach were the introduction of human resource management as a strategic driver (Popescu et al, 2022) and an integrated approach to employee management and development (Albrecht et al., 2015). Performance management and should not be a once-off annual event coordinated by the Human Resources Management Department which unfortunately is often the case.

Purpose of Performance Management

Performance management is about aligning the organisation’s employees to the requirements of the organisation, and aligning organisational culture with performance (Tan, 2019). Establishing a performance management system can be difficult, and any or all of the following may prevent a smooth implementation and ongoing system maintenance:

- organisational culture (Kuo and Tsai, 2017),

- leader commitment and expertise (Oygarden et al., 2020),

- employee engagement (Sandhya and Sulphey, 2020),

- legal obstacles – this may include contractual, civil, and employment law considerations,

- industrial obstacles.

To implement a performance management system and maintain it once it is operational, the organisation must clearly articulate and manage workforce expectations and executive management . It is essential to establish role and goal clarity for the system, but most importantly, for the workforce using the performance management system (Justin and Joy, 2022). Team members must understand their roles and be clear about their expectations. To do otherwise would be unfair to them and damaging to the organisation. The performance management system provides an opportunity to identify and act upon support that employees require to give them the best possible opportunity to attain the mutually agreed goals.

Empirical data shows that future career aspirations are important to employee engagement (Cattermole, 2018, Barhate et al, 2021). When these are achievable, retention of valuable employees is more likely. However, the performance management system also identifies those employees that warrant further development for future leadership positions. Thus, identifying developmental needs in employees identified for advancement or promotion becomes an integral part of the system (Justin and Joy, 2022).

The other purposes of performance management are monitoring and reviewing employees’ performance and determining their performance level in terms of their work standards, work output and outcomes, and other measures agreed upon with the employee. These performance levels are used to assess the degree to which agreed targets are achieved. Effective performance management recognises good performance, demonstrates areas that could be improved, and identifies areas of employee performance that the organisation must address (Karolina, 2012).

The purposes and the objectives of performance management relate to:

- aligning employees to organisational requirements,

- clearly articulating and managing expectations,

- establishing role and goal clarity for all in the organisation,

- providing an opportunity to discuss and plan for future career aspirations,

- monitoring and reviewing employee performance, and

- monitoring and maintaining standards of performance against expectations.

Recognition of good performance

It is unlikely that well-led organisations would not have some sort of employee performance management system in place. This could be as simple as an annual discussion, a file note in a personnel file, or a quick chat over some workplace issue that has emerged. These are all important parts of the system; however, they are only a small part of a performance management system. Some organisations have an ‘employee appraisal system’ that is more commonly undertaken annually after a qualifying or probationary period. The most often asked question when discussing workforce performance is, “How does performance management differ from performance appraisals or staff reviews?”. The simple answer is that the deployment of performance management promotes employee activities and outcomes congruent with the organisation’s strategic goals and objectives and may entail specifying the activities and outcomes that will result in the organisation successfully implementing the strategy.

An effective performance management process:

- Creates a planning hierarchy that links individual employee objectives with its mission and strategic plans. However, the important part is that the employee clearly understands how they contribute to achieving the overall business objective.

- Sets clear performance objectives with the employee, thereby managing the expectations of the employee and the organisation.

- Documents individual or team development plans in partnership with the individual or team members, which will underpin the achievement of the performance objectives.

- Formally provides feedback, encouragement, and guidance of the employee by conducting regular discussions throughout the performance cycle, including coaching, mentoring, feedback, and assessment.

The Differences Between Performance Management and Performance Appraisal

There is a difference between performance management and performance appraisal. The definition of performance management was discussed earlier in this chapter. The issue relates to the lived experiences of many health workforce members because they associate performance management with an annual performance review. In comparison, performance management is about what might assist an employee to continue developing to improve their performance. For the employing organisation, this refers to the methods used to evaluate the progress toward goals mutually set between the individual or team. There is regular discussion on these goals between the parties during the year rather than at the end (Justin and Joy, 2022). In earlier times, performance appraisal referred to judging an employee’s past performance based on criteria not necessarily individualised to the employee (Justin and Joy, 2022). This is the reason why early forms of performance appraisal placed no obligations on the organisation. It probably did not have reliability and validity in terms of what it measured and now performance management has shifted the focus from an annual event to an ongoing process. What needs to be understood here is that performance appraisal is about the past whereas performance management is about the future and uses previous experiences with the staff member to focus on the future. This means the appraisal process reviews the employee’s performance in the immediate past, while performance management focuses on the present and the future.

The table below highlights the differences between performance management and performance appraisal.

Differences between Performance Management and Performance Appraisal

| Performance Appraisal | Performance Management |

| Considered more operational than strategic. | Can be considered more strategic than operational. |

| Top-down assessment. | Involves a dialogue between the leadership and team member or members. |

| Undertaken retrospectively to correct mistakes or tardiness. |

Undertaken prospectively to develop team members and is future-oriented. |

| Often uses rankings or ratings to assess progress, mostly annually. | Ongoing and continuous reviews interspersed with more formal measures. |

| Rigid structures and systems. | Flexible process tailored to the developmental needs of the team member(s). |

| Often it is not linked to the employing organisation’s strategic goals and objectives, including business needs.

|

Linked inextricably to the strategic goals of the organisation, including business needs. |

| Usually takes a quantitative assessment approach using rating scales and rankings.

|

Usually is a mixed methods approach (quantitative and qualitative) in combination. |

| This is an individual activity relating to a specific team member.

|

It may be an individual activity but also a collective one because it can accommodate a whole team approach. |

| Often linked to remuneration, such as an increment payment after a defined service period. | Not usually linked to remuneration. |

Activity

Watch the embedded video, identify the problems or issues with how this performance appraisal is performed, and write them down.

While there are only a few minutes of the performance appraisal shown in the video, several significant issues must be addressed. For each problem or issue identified, please describe what is required to correct them.

Reflect on your experiences with performance appraisal, and if there were similar issues or concerns, how did that make you feel?

Source: Brown, M. (2010) The performance appraisal from hell. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Jln-liAnN8Y

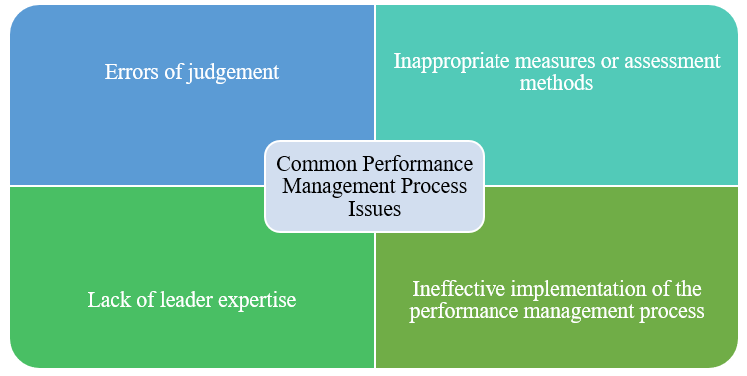

Common Performance Management Problems

Common problems associated with performance management are summarised into four themes, as demonstrated in the figure below.

Activity

Using the four themes detailed in the thematic analysis shown in the figure above, sort each of the common problems discussed below into one or more of the four themes. A problem or issue may be relevant to more than one theme.

Managing Expectations

This occurs particularly when the performance management system requirements and outputs are poorly communicated to employees, causing the team member and the leader to enter these discussions with low confidence levels. Poorly managed expectations are often due to a lack of operating rules, observance of those rules, and even knowledge about how to go about the performance review process when coupled with a lack of understanding of the expected outcomes. There is little chance of fruitful discussions benefiting the team member or the organisation.

Moreover, because these discussions are often infrequent, the employee may view them as an opportunity to discuss remuneration, promotion prospects, and other issues. Domination of the discussion related to employee content rather than understanding the achievements and what is now required to satisfy organisational requirements or team member’s interests and abilities may occur. This can lead to a vague definition of performance goals and perpetuate poorly defined and executed performance reviews. Given that the performance review process is often an annual process, leaders and team members may find it difficult to remember what happened during the year, let alone forge a partnership of benefits to both the employee and the organisation. Typically, it is true that both come to the meeting ill-prepared, and there is little meaningful discussion. The situation makes the performance review more difficult and frustrates both team members and leaders.

Timing Issues

In many organisations, appraisals are undertaken annually and related to the team member’s work anniversary. Thus, it is only possible to align, at best, 50% of the staff with future objectives, assuming there is an even distribution of start dates across the workforce. Given that most appraisal systems are not automated, there is poor reporting and low visibility of who achieved their objectives.

Advancement/Promotion Not Inherently Tied to the Performance Review

Since many organisations conduct performance reviews annually, most line managers only seriously think about and plan for these once a year, which is a primary cause for employees leaving the organisation. There is a lack of competency assessment in most performance management systems. They also often lack an active development plan to which the employee and manager mutually agree. Staff are often disillusioned and leave the organisation if they can see no personal development prospects or if personal development has not occurred in practice for the last several years, despite many promises.

Performance management implementation requires specific objectives tied to the strategic and operational plans. When this occurs, organisational performance outcomes will increase quickly.

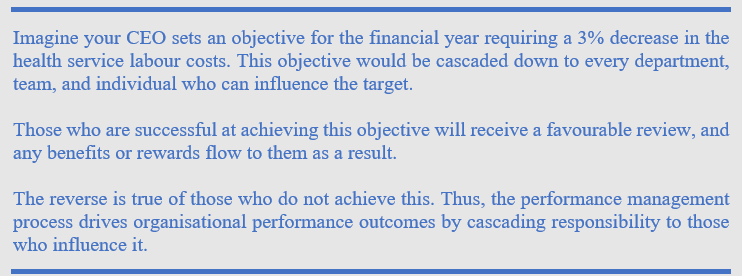

Example

In the example provided above, the team members and leader enter the process with better confidence levels, as the objective that provides the rule stipulates what assessment will entail and how it will be implemented. Team member evaluations related to the achievement of objectives occur as planned once they are clear to the team member and the leader. It is important that what constitutes the three per cent decrease in labour costs is agreed upon between the leader and the team member or members. The outcome is that the leader and the team members have an informed discussion and focus on achieving personal and business objectives, not irrelevant issues. The performance review is a part of an ongoing process, not just an annual procedure. The performance process requires that discussion and performance measurement occurs more often than annually. The agenda for that discussion is about performance against target and what the team members need to achieve the objectives and strategies. In a good performance review process, what team members need to achieve the requirements is part of the overall planning process. Moreover, emotional discussions can be displaced by business-focused discussions on achieving objective outcomes.

Subjective Assessment, Invalid and or Unreliable Tools, and Unreliable Measures

These three significant issues make the process of annual performance appraisal meaningless. If this is examined purely from the team member’s perspective, it is easy to recognise that team members feel that their future depends on their leader. This is not conducive to the support and development of the employee necessary in contemporary organisations.

Rules and Requirements Not Known by All Employees

In many organisations, all parties lack an understanding of the governance of the performance management process. When team members and leaders enter the process knowing the ‘rules of engagement’, they have more confidence because ‘rules’ stipulate what is being assessed and how. The assessment of team members is based on their achievements of clearly identified and agreed objectives. Leaders then have a better framework to determine an employee’s performance as they are familiar with the assessment criteria. The outcome is that both parties have an informed discussion and focus on achieving both personal and business objectives, not on irrelevant issues. The performance review process is then just a part of the process, not simply an annual procedure, and requires discussion more frequently than annually. The agenda for that discussion is about performance against target rather than employee needs. This is necessary because, as already discussed, the team member’s needs are already factored into the strategies designed to meet the target.

A properly implemented performance management system requires managers and employees to commit to three things:

- A competency review of the team member’s work towards meeting the set objectives.

- A team member’s development plan.

- Regular monitoring meetings between the team member, or team, and the leader.

Implementing the performance management system in these ways means that the employee experiences personal development and becomes more engaged with the organisation. Team members feel they have a voice in the organisation and therefore feel part of it, with a growing understanding of the relationship between themselves and the organisation. Managers feel more confident in the team member’s expectations, and the team member’s wishes are also central to the discussion.

Performance Management and Employee Engagement

Employee engagement refers to unlocking employee potential to strengthen organisational and employee performance, resulting in discretionary effort and increasing the team member’s self-efficacy, which is important to achieving objectives and targets. Self-efficacy relates to the individual’s belief in their capacity to produce specific performance attainments. It combines employee potential and organisational performance to create a highly engaged workforce. Carter et al. (2016) found that human resource management practitioners (HRM) should address self-efficacy and employee engagement, as doing so boosts job performance.

Performance reviews also concern the treatment of team members and how leaders relate to others within the organisation. Leaders and team members share responsibility for creating the organisation’s future by being clear and aligned on mission, purpose, and goals through continuous communication, individual development, and creating opportunities for those employees who are top performers. Understanding that employee engagement is not a program, but part of organisational culture is essential.

Performance management is therefore about keeping the dialogue open with team members, working in partnership with them to achieve the organisational goals set, and allowing some locus of control to rest with them so that they are part of the solution. Lappalainen et al. (2019) investigated the relationship between performance management and employee engagement. Their study, founded on stakeholder analysis, contained a significant finding that employee engagement is driven more by the inherent attitudes of employees than environmental factors present in the organisation. The Lappalainen et al. (2019) study found that employee engagement was more related to the ability of team members’ skills in analytical thinking, their level of extroversion, systems thinking assertiveness, and leadership. The recommendations that emerged from this study suggest performance management should concentrate on developing these soft skills in the workforce to increase stakeholder (in this case, team members) engagement.

Legal and Industrial Implications Relating to Performance Management

Labour and employment laws do not mandate performance management but prohibit discriminatory employment actions based on non-job-related factors. Training leaders and team members on job evaluation fundamentals is vital if an organisation develops a performance management system. Consistent application, unbiased evaluation, and timeliness are the three core elements of effective performance management. When these three core elements are not evident, it leaves the organisation open to complaints from team members that could end up in a legal or quasi-legal proceeding initiated by either the employee or their union.

When fully implemented, a performance management system may identify how team member and organisation targets are aligned, determine whether an employee is promoted or even kept on staff, and justify salary increases. On this basis, they are useful for many employment decisions, and fair implementation of the review manages the legal and industrial aspects of performance management. Conducting them properly and fairly means that all employees are subject to having their job performance evaluated and using the appraisal rating for the same reason. Another application related to legal risk management of the performance management process is that organisations sometimes use performance management to have a legally defensible means of making employment and job decisions that will discourage frivolous lawsuits, or ensure the organisation is likely to win a court or tribunal decision.

Performance management can also be viewed as a risk management strategy that, if implemented and supported properly, can provide some protection provided it is done properly, particularly concerning discrimination allegations or equal employment opportunity complaints. Keep in mind that it is always the courts that decide on the merits of a particular case. It is reasonable to ask what legally defensible performance management systems’ characteristics are. The meaning of defensible is that:

- Employees participate in establishing performance standards for their position.

- The standards used are relevant to the essential elements of the job, are documented, and available to all employees.

- Employees are informed of, understand, and sign off on critical job requirements and expectations before the appraisal.

- The system should not be a comparison between employees.

- Employees are allowed and encouraged to be a partner in the process.

- Employees are informed of any performance problems and issues and allowed to rectify the problems.

As a result of early union bargaining, workers today enjoy a variety of benefits, such as a legal minimum wage, workplace safety standards, paid overtime, health care, and a defined working week in terms of hours at ordinary pay. As a result of unions, union members often receive higher pay and better benefits than equivalent non-unionised workers. Unions have worked in partnership with organisations to improve the sector regarding occupational health and safety, remuneration and reward, time and attendance issues, and employee rights.

The best strategy for dealing with union involvement in performance management is to consult early and invite the relevant unions to be part of the overall process. That way, unions can be part of the solution.

Training and Development of Team Members in the Health and Social Care Workforces

One of the critical factors in employee motivation and retention is the opportunity for employees to continue growing and developing job and career-enhancing skills. Developing personally through training is one of the most important factors in team member motivation and, by necessity, engagement.

Before we examine various workforce training and development methods, it is essential to understand that a manager can significantly impact training and development through the responsibilities ascribed to an employee in their current job. The goals of training and development are to:

- embed lifelong learning,

- provide for employee engagement and voice, and

- promote a performance culture in the organisation.

The following strategies are considered excellent opportunities for employee development and engagement. They will assist in improving organisational systems and processes and provide opportunities for team members to be confident in what they are doing and why they are doing what they do.

Seven Strategies for Employee Engagement and Development

- Expand the job to include new, higher-level responsibilities and stretched but attainable goals, and allow them to experience success in their work and additional assigned responsibilities.

- Reassign responsibilities that the team member does not like or are routine, where possible, practical and safe.

- Invite the team member to contribute to the more important department or organisation-wide decisions and planning.

- Provide more authority for the team members to self-manage and make decisions.

- Assign the team member to lead projects or teams.

- Provide more information by including the team member on specific mailing lists in organisation-wide briefings.

- Provide more access to essential and desirable meetings.

The Importance of Training and Development in the Workplace

The opportunity for team members to engage in training and development opportunities cannot be underestimated. It is important to emphasise here that workplace training and development requires budget allocation if leaders are to maximise the benefits. The costs associated with training and development include time off to participate and whether there is a need to backfill team members. The costs associated with other required resources may appear excessive on first examination. However, the benefits, including cost benefits, are well documented in the literature (Coulson‐Thomas, 2010; Zgrzywa-Ziemak and Walecka-Jankowska, 2020).

The benefits listed below demonstrate the importance of training and development in the health and social care workforce and illustrate the importance of training and development in the health and social care workforce. Training and development provide teams with:

- A clear conception of their role and responsibilities. Onboarding and orientation are clear examples of this. Team members better understand their organisational role when they have access to up-to-date training and resources.

- Improved team member morale and engagement. Job satisfaction and commitment are vital in the workplace. When organisations actively invest in their workforce, it demonstrates to the workers that they are valued. This promotes a good organisational culture and a positive relationship between leaders and team members. This positive relationship emanates from team members feeling that they are actively learning and developing in their roles and the organisation. This increases their work satisfaction and avoids the feelings of stagnation experienced when team members continue to do the same things over and over in a working week. When offered the opportunity to gain experience, team members will feel the organisation is investing in their future, strengthening loyalty and engagement with the work and the organisation.

- The means to attract and retain valuable team members. The costs involved with recruiting new staff are considered alongside the costs associated with training and development. As such, it is beneficial to invest time and resources into training and developing existing team members. As with the previous point, demonstrated investment in the workforce strengthens organisational culture and loyalty, and research consistently asserts that investing in team members nurtures loyalty, as they are less likely to seek a new challenge with another organisation. This avoids further recruitment and selection costs, including advertising and interviewing. Team members will increase net promotor scores; thus, marketing that the organisation provides regular training, which is a great incentive to attract other candidates.

- Leadership training opportunities for emerging leaders. If a leadership position unexpectantly becomes available, this results in increased use of resources and decreased productivity during the search for a replacement. This can leave the organisation exposed until the vacancy is filled. However, when an organisation prepares for such a risk and implements a leadership development program crafted specifically for organisational needs, the risk is decreased by ensuring that underqualified team members are not left with the responsibilities. Leadership training is a risk strategy that will provide leadership training for relevantly qualified and interested team members and can save considerable financial and other resources and provides a means for leadership continuity. Any organisation that keeps evolving limits disruption.

Approaches to Learning That Underpin Training and Development

The evidence-based approaches to organisational learning to consider when organisations must consider planning training and development opportunities include, but are not limited to, those outlined below.

Behavioural Approaches

Behavioural learning theory, or behaviourism, is a common concept that educators and business leaders may use to encourage positive behaviours (Kuhl et al., 2019), and in the case of training and development, this means in the workplace. The behavioural approach is based on stimulus/response conditioning. The instructor must show factual knowledge and observe, measure, and modify behavioural changes in a specified direction. Behavioural approaches target conditioned responses or the commitment to the memory of facts, assertions, rules, laws, and terminology. The correct response is achieved through the stimulation of the senses.

Cognitive Approaches

Cognitive approaches assert that humans generate knowledge and meaning through the sequential development of an individual’s cognitive abilities (Kuhl et al., 2019), such as the mental processes of recognition, recollection, analysis, reflection, application, creation, understanding, and evaluation. The cognitivist learning process refers to learning techniques, procedures, organisation, and structure and developing an internal cognitive system that strengthens synapses in the brain. The learner requires assistance in developing prior knowledge and integrating new knowledge.

Humanistic

Humanist learning theory describes learning as a function of the entire person, coupled with the belief that learning is impossible unless both the cognitive and affective domains are involved (Schneider et al., 2015). For humanist approaches, the learner’s ability for self-determination is paramount. For example, humanists promote a sense of individual control over their learning and work. Team members grow exponentially with success and improve when achievements are recognised and reinforced. Respecting the whole person in a supportive environment can encourage learning. Learning is also fostered through structuring information appropriately and presenting it in meaningful segments with feedback.

Constructivist Approaches (also known as transformative approaches)

The constructivist approach considers learning as the ability to think autonomously (Schneider et al., 2015). It is usually (but not exclusively) applied in pedagogical approaches designed for adult learning (Demick and Andreoletti, 2003). It allows learners to be individual in their thinking, develop a sense of meaning, engage in “autonomous thinking”, and learn by using contexts of their formal learning experiences to construct and reconstruct personal meaning. This phenomenon is a uniquely adult form of metacognitive reasoning. Metacognitive reasoning involves actively and assiduously assessing reasons, providing arguments that support beliefs, and resulting in decisions to act. Thus, beliefs are justified when based on sound evidence-based grounds. The reasoning process may involve such tacit knowledge as aptitudes, skills, and competencies.

Determining Training Needs

A training needs analysis (TNA) reviews an organisation’s learning and development needs by considering individual needs, the operational needs of units and departments, and the organisation’s needs. The TNA examines the knowledge, skills, and behaviours those working in the organisation require and how these can be developed effectively. A TNA is essential to deliver appropriate and effective training that meets the needs of individuals and the organisation and represents value for money. There are three phases to a TNA that are interlinked.

- Individual (Person) Analysis

- Operations (Task) Analysis, and

- Organisation Analysis.

Determining the health workforce’s training needs is a significant task, complicated by the many types of occupations and situations of team members. Coupled with an ageing and diverse workforce, ensuring that robust and appropriate systems meet training needs and processes is key to the success of training offerings.

The key issues to address in designing a training needs analysis are:

- know the present situation,

- identify the required competencies,

- consult with employees,

- make the results of surveys or consultations known throughout the organisation,

- prepare specific employee developments,

- implement the plans, and

- evaluate the success of the plans.

Watch the below embedded video about the essentials of conducting a training needs analysis that demonstrates the application of these principles.

Source: Tobing, H, (2013) Training Needs Analysis (TNA). https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=X3cSAjHDeag

Effective training is an important element of a successful organisation. Training needs require systematic examination whilst considering the competencies for the various jobs in any health care organisation. There is little point in offering and implementing a training program based on the latest fad or because some other organisation is using it. This systematic process consists of undertaking analyses of the following:

- The competency required of an individual who must perform a specific job.

- What area or group in the organisation needs the training.

- What the employee must learn to satisfy the competencies.

- Who needs the training, and what specific training is needed.

Kirkpatrick’s (2007) Four Levels of Evaluation contain these processes. The model is a globally recognised method for evaluating training and learning outcomes for both formal and informal training and allows for rating against the four levels established in the model. The model is useful for designing evaluations of training and development deployed by the organisation and provides a useful tool to determine the effectiveness and reach of the training activities. Such analyses must be undertaken by people trained and skilled in using the model.

Key Takeaways

Appropriate training and development for team members are aligned with system and process improvements, making it easier for employees to know what they are doing and why they are doing it. Team members who do not have a clear idea of their expectations of them can severely impact their job performance.

Training and development provide great opportunities to expand the knowledge base of all team members and team leaders. However, many organisations such as health and social care find development opportunities expensive in tight fiscal climates. They are often unsure about or unwilling to commit the necessary resources to implement employee training and development opportunities successfully, and this is problematic, particularly when this should ideally be linked to with performance management goals. Team members who attend training also miss work time, and there is recognition that this may impact service delivery while the team member is absent from the work area. However, it must always be clear that training and development provide both individuals and organisations with benefits that make the cost and time a worthwhile investment.

References

Albrecht, S. L., Bakker, A. B., Gruman, J. A., Macey, W. H., and Saks, A. M. (2015). Employee engagement, human resource management practices and competitive advantage: An integrated approach. Journal of Organizational Effectiveness: People and Performance.

Anna, Z. Z. (2016). The Impact of Organisational Learning on Organisational Performance. Journal of Management and Business Administration. Central Europe, 23(4), 98-112.

Barhate, B. and Dirani, K. M. (2021). Career aspirations of generation Z: a systematic literature review. European Journal of Training and Development, 46(1/2), 139-157. https://doi.org/10.1108/ejtd-07-2020-0124

Bersin Academy. 2020. The History of Performance Management. Josh Bersin Academy Youtube Video https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YqdR_ejViMI

Carter, W. R., Nesbit, P. L., Badham, R. J., Parker, S. K. and Sung, L.-K. 2016. The effects of employee engagement and self-efficacy on job performance: a longitudinal field study. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 29, 2483-2502.

Cattermole, G. 2018. Creating an employee engagement strategy for millennials. Strategic HR Review, 17(6), 290-294. https://doi.org/10.1108/shr-07-2018-0059

Coulson‐Thomas, C. 2010. Transforming productivity and performance in healthcare and other public services: how training and development could make a more strategic contribution. Industrial and Commercial Training, 42, 251-259.

Demick, J. and Andreoletti, C. 2003. Handbook of adult development, New York, Kluwer Academic/Plenum.

Galeazzo, A., Furlan, A. and Vinelli, A. 2021. The role of employees’ participation and managers’ authority on continuous improvement and performance. International Journal of Operations & Production Management, 41, 34-64.

Justin, E. and Joy, M. M. 2022. Managing the most important asset: a twenty year review on the performance management literature. Journal of Management History, 28(3), pp.428-451.

Karolina, M. 2012. Leader-Member Exchange and Individual Performance. The Meta-analysis. Management, 16(2), 40-53.

Kirkpatrick, J. 2007. The hidden power of Kirkpatrick’s four levels.(Donald Kirkpatrick’s four levels of training evaluation). T+D, 61, 34(4).

Kuhl, P. K., Lim, S.-S., Guerriero, S. and Damme, D. V. 2019. Developing minds in the digital age: Towards a science of learning for 21st Century education. Paris: OECD Publishing.

Kuo, T. and Tsai, G. Y. 2017. The effects of employee perceived organisational culture on performance: The moderating effects of management maturity. Total Quality Management & Business Excellence, 30, 267-283.

Lappalainen, P., Saunila, M., Ukko, J., Rantala, T. and Rantanen, H. 2019. Managing performance through employee attributes: implications for employee engagement. International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management, 69, 2119-2137.

Mukarramah Modupe, A., & Sulaimon Olanrewaju, A. (2017). Employee Motivation, Recruitment Practices and Banks Performance in Nigeria. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Knowledge, 4(2), 70-94.

Noto, G. and Noto, L. 2018. Local Strategic Planning and Stakeholder Analysis: Suggesting a Dynamic Performance Management Approach. Public Organization Review, 19, 293-310.

Oygarden, O., Olsen, E. and Mikkelsen, A. 2020. Changing to improve? Organizational change and change-oriented leadership in hospitals. Journal of Health Organ Manag, ahead-of-print, 687-706.

Popescu, C. R. G., & Kyriakopoulos, G. L. (2022). Strategic Human Resource Management in the 21st-Century Organizational Landscape: Human and Intellectual Capital as Drivers for Performance Management. COVID-19 Pandemic Impact on New Economy Development and Societal Change, 296-323.

Presbitero, A. and Teng-Calleja, M. 2019. Subordinate’s proactivity in performance planning: implications for performance management systems. Asia Pacific Journal of Human Resources, 57, 24-39.

Rodriguez, J., & Walters, K. (2017). The importance of training and development in employee performance and evaluation. World Wide Journal of Multidisciplinary Research and Development, 3(10), 206-212.

Sandhya, S. and Sulphey, M. 2020. Influence of empowerment, psychological contract and employee engagement on voluntary turnover intentions. International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management, 70, 325-349.

Schneider, K. J., Pierson, J. F. and Bugental, J. F. T. 2015. The handbook of humanistic psychology: Theory, research, and practice. Second edition ed. Thousand Oaks, California: SAGE Publications, Inc.

Tan, B.-S. 2019. In search of the link between organizational culture and performance. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 40, 356-368.

Zgrzywa-Ziemak, A. and Walecka-Jankowska, K. 2020. The relationship between organizational learning and sustainable performance: An empirical examination. Journal of Workplace Learning, 33, 155-179.