Organisation and governance

Governance and financial management in health and social care

John Adamm Ferrier and Hanan Khalil

Introduction

This chapter explores the relationship of finance in the delivery of healthcare and social care by examining how funds are governed, raised, pooled, and distributed. The chapter examines the funding sources for health and social welfare in Australia; where and how funds are sourced, pooled, and managed; methods of payments from an individual’s perspective; as well as how funds are distributed to hospitals and health services. We review the five common funding methods used in health delivery, and then examine how governance ensures quality outcomes through financial reporting.

Over the last century, healthcare and social care have evolved from a charitable and benevolent focus towards becoming highly commercial in nature (Collyer & White, 2001). Healthcare, that is, the provision of services that permit an individual to return to a state of well-being, has become more complex (Braithwaite et al., 2005), involving collaboration to achieve both direct or indirect care (West, 1992) and demanding resources in terms of human inputs, equipment, and consumables. Medicare is the main funding body for the provision of health services in Australia. To provide access to medications, the Australian government subsidises the cost of medicine for most medical conditions under the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme. Australians also have the option to purchase additional insurance from private health insurance companies for health services not covered by Medicare, such as dental and ancillary services, or for accommodation in a private hospital.

Social care, or welfare, is a broad topic. The Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (2021) describes welfare as supporting individuals, families, and even communities who require assistance to achieve positive well-being. The International Labour Organization (2023) lists the minimum standards for social security that include “medical care, sickness, unemployment, old age, employment injury, family, maternity, invalidity and survivors’ benefits”.

In Australia, funding for these services is predominantly public via Commonwealth Government departments. Other funding is provided for health related services by the Department of Health and Aged Care Services (statutory authorities are Medicare and the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme). The Department of Social Services provides welfare related funding through the statutory authorities of Centrelink (pensions, etc) and the National Disability Insurance Agency (which oversees the National Disability Insurance Scheme [NDIS]. There are additional funding sources in Australia, such as those provided by the Department of Veteran’s Affairs and state government authorities that insure for specific purposes, such as workplace injuries and road trauma.

Regardless of whether a health service is privately or publicly owned; or how it is funded, understanding financial management is now crucial for all managers. (Braithwaite et al., 2005; Courtney & Briggs, 2004; Duckett & Willcox, 2015; Edwards, 2015). Clinical managers must understand financial information and develop the skills to effectively communicate with financial staff.

Healthcare needs and costs vary over the span of an individual’s life. Assuming an uncomplicated birth, the average lifetime healthcare costs are higher for females than for males; healthcare costs are lowest in childhood, and rise relatively slowly until after the age of fifty, where they start to increase (Alemayehu & Warner, 2004; Meerding et al., 1998). For the poor, serious ill health may swiftly become catastrophic, not only in terms of treatment costs, but also with respect to the potential loss of income (Kutzin et al., 2017; Li et al., 2014). The highest costs occur in the final years of life, and in the absence of some form of cost sharing of the financial burden, can contribute to intergenerational poverty (Li et al., 2014; Shan et al., 2016).

The World Health Organization (2021) determined that all citizens should have access to universal health coverage as a basic human right, meaning that a person should receive timely and responsive provision of essential healthcare without becoming impoverished. The evolution of health service provision in any nation depends on the population’s historical developments and cultural expectations and is often shaped by political debate. This contributes to international diversity regarding the way health systems are structured, governed, regulated, and financed. Governments face a range of choices and priorities with respect of achieving improvements in population health (Duckett & Willcox, 2015, p. 7). Most countries who are members of the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (2016) implement forms of universal healthcare coverage so that the costs and risks associated with healthcare provision do not fall to the individual.

At its heart, universal healthcare coverage requires the pooling of resources and sharing of risks of potential future health needs across a population. A wide diversity of health systems and the way they are financed exist across the globe. In designing a health system that features universal healthcare coverage, decisions are based on a given population’s needs and, perhaps most importantly, who will contribute funds and who will benefit.

- United universalism, where citizens have access to the same opportunity for healthcare regardless of their ability to pay, through government operated schemes as seen in the United Kingdom’s National Health Service, Medicare in Australia and Canada, New Zealand Health, and the Unified Health System in Brazil.

- Stratified universalism, where access to care is available to all, but limited by their ability to pay, the insurance is provided through private or commercial health insurance, with additional provisions made for those who cannot afford healthcare.

- Differential access, where portions of the population cannot access any form of insurance and must rely on out-of-pocket expenditure.

In Australia, Medicare is an example of national health insurance, where the citizens and eligible residents have access to healthcare, regardless of their personal ability to pay. While it is funded by a levy on all personal income tax, most Medicare funding comes from general government revenue. The Australian private health insurance industry operates under a requirement called community rating, where (apart from some qualifying periods) the insured pays the same contribution for the insurance product regardless of their past health history or risk of developing an illness and those classified as low risk effectively subsidise those with a high-risk profile (Lo Sasso & Lurie, 2009). Without such a policy, private health insurers would follow the American model of experiential rating and vary premiums or even deny care based on risk by charging higher premiums for groups considered to be at higher risk, such as older people, current or former smokers, or those with chronic diseases.

Strategies to pool funds and spread the risks associated with future ill health are not mutually exclusive. Although every taxpayer in Australia contributes to Medicare through a surcharge, Australians may also choose to take up discretionary options in addition to Medicare. A list of potential pooling strategies is listed in the table below.

Table Pooling options

| Level | Description | Capacity | Example(s) | Risk | Potential benefits | Potential disadvantages

|

| Individual | Where a person funds their care from their personal resources.

Favoured by the affluent as an expression of “self-determination” and/or “freedom from government interference”. |

Low – constrained by access to economic resources throughout a lifetime: relatively high for the affluent, inaccessible to the poor.

Requires discipline to achieve. |

Individual health fund (e.g. health account. | Inability to afford care that may be required for serious or unexpected illnesses or accidents/mishaps.

Funds are only used for personal health needs, negligible contributions to public health (social goods). |

If economic resources are limited, funds may be redirected to meet more pressing immediate needs such as accommodation and food.

Control of the accumulated funds, preserved for the sole use of the individual. |

Healthcare is progressively becoming too expensive for an individual to fund.

Unmet healthcare needs. Health provision becomes a societal “luxury” item rather than a universal service. Poverty and chronic disease are more likely in old age. Reliance on charity. |

| Family | Funds are pooled by family members and used to assist those who fall ill.

Requires careful pooling and prudent management of family wealth across generations. |

Relatively low – constrained by access to economic resources, pooling of family wealth over generations. | Family trusts, extended family collectives. | As above, in addition to intergenerational poverty. | Cohesion of the traditional and extended family unit, clan membership.

Benefits high status and wealthy members of a hierarchical society. |

Unmet health needs, inequality among family members may lead to favouritism.

Hegemonic patriarchal structures potentially disadvantage females in favour of males. Contributes to the establishment of a hierarchical society and privileged behaviours and expectations. |

| Social | Where groups of people contribute towards a common fund with a common contribution and expressed outcomes. | Moderate – presumes that not all members will require resources at the one time.

Capacity increases over time, but is susceptible to being wiped out in an epidemic or other calamity affecting the community. |

Friendly societies, guilds,

alms (historical forerunners of private health insurance organisations) |

Inability to cope with medium to large scale disasters that affect all contributing members at the one time, such as epidemics.

Potential for contributions to public health (social goods). |

Social cohesion of the local population’s environment.

Reduction in sedition arising from social unrest. Strengthens the role (and purpose) of religious and other benevolent communities. |

Healthcare access and security rely on social status within the contributory group.

Regional and community health inequities. Restriction on geographical mobility. Can be used to enforce social conformity. Inequality for nonconformists and/or minorities. May be subject to religious dogma or social prejudices. |

| Work-related | Where health insurance forms part of the employee’s remuneration package that extends to their spouse and dependents. | Dependent upon the size and stability of the work environment.

Low to moderate – if the fund is managed internally. Moderate to high if premiums are purchased from private health (reinsurance. |

Company sponsored health insurance schemes.

|

Inability to cope with medium to large scale disasters that affect all contributing members at the one time, such as epidemics.

Potential for contributions to public health (social goods) but constrained by perceived economic benefit to the company. |

Employer benefit: creates incentives for workers to remain with the company.

If internally managed, creates a fund that may be invested to benefit the parent company. Can reduce personal income tax obligations. |

A disincentive for employees’ workplace mobility.

Benefits end with employment. Invested funds belong to the company rather than the workers. Personal income tax is replaced with fringe benefits tax, which is factored into the remuneration package. |

| Indirect taxation/levy

Premiums are indexed according to actuarial risk associated with the type of industry and the employer’s history of claims. |

High – if guaranteed by government. | Indirect taxation/levy for Workcover insurance as a salary on cost. | Premiums may not cover the lifetime costs associated with permanent injuries or disabilities. | Raises funds for the treatment of injuries incurred in the workplace.

Encourages workplaces to institute work safety practices to avoid increased premiums. |

Indirect charge (staffing overhead) not visible to workers, therefore little personal financial incentive to ensure a safe workplace.

People must disclose previous Workcover claims if seeking a new role – may impact employment opportunities. |

|

| Private health insurance | Commercial companies that offer insurance products for a regular premium payment from individuals.

Companies may be publicly listed private companies that pay dividends to shareholders, or not for profit organisations that reinvest surpluses back into the fund. |

Moderate to high – dependent upon the volume of members or purchasers and presence of an industry wide opportunity to reinsure through a common pool. | “Not-for-profit” companies where surpluses are invested back into the fund.

“For profit” private companies surpluses contribute shareholder dividends. |

Subject to economic downturns.

Without a reinsurance pool, insurance companies’ risk insolvency in periods of high demand. Higher potential for contributions to public health (social goods), but this is constrained by perceived economic benefits to the company through a reduction in health burden via preventative health. |

Risk is spread across all members, the more members the better.

In the absence of universal (nationwide) schemes, this is a good option if appropriately regulated and reinsurance mechanisms are provided. Provides subscribers with a sense of security and potential of choice regarding their health providers. |

Without government regulation, (i.e., community rating) can impose higher premiums on those who are deemed to have pre-existing conditions or who may be at risk or needing benefits.

May have complex exclusion rules, benefits are determined by actuarial study and commercial viability rather than matching health needs. Often out of reach of those who are socioeconomically disadvantaged (i.e. those who need it. |

| State-sponsored insurance | Systems of funding healthcare that can either be managed as part of a government department, instrumentality or, in some cases, outsourced to existing insurance companies. | Highest capacity to cope with collective health needs across a national or regional area.

Strong capacity for collection of reliable data. |

Medicare Australia (national universal payer). | Financial risk spread across the population. | Widest capacity for revenue collection.

Mechanisms that can achieve equality across regions and nations. Strong capacity for funding preventative health programs. Transparent redistribution of economic resources to benefit the socially disadvantage. |

Challenging to meet demand.

Perception of “rationed” care. Can be mired in bureaucracy and slow to adapt. May not provide comprehensive coverage (e.g. Medicare Australia does not cover dental care. |

Funding Flows and Access to Health Services

One of the challenges in determining how to address funding a health system is that the “health market” is vastly different from what may otherwise be considered a “perfect market”, where the behaviours of customers and sellers cause equalisation. The health market operates with information asymmetry (sellers have more information than buyers). The transactions are not independent, health provision includes both private and public goods, health provision is not inherently selfish, and although there are many buyers (patients), the sellers (practitioners) are restricted and subject to regulation, and the products are heterogenous, which means the product has different characteristics compared to other products. (Legge, 2015) emphasised these differences.

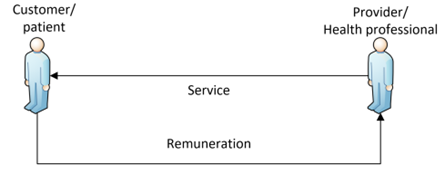

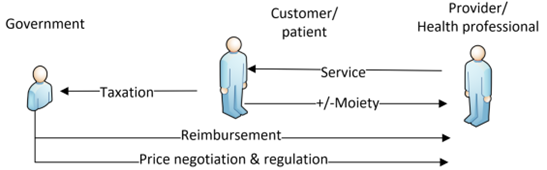

The simplest funding relationship is between the customer and the provider, in that services are provided in exchange for something of value. This is a direct payment model, where the customer (the patient) is responsible for meeting all of their costs, and the provider is free to determine the charges they will make, as shown in the figure below.

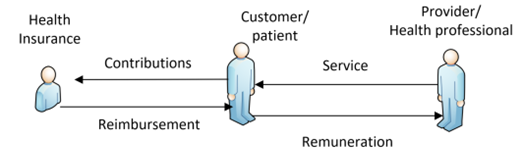

Where a patient voluntarily enters into a health insurance arrangement, the patient may then seek reimbursement of the costs associated with the care provided after paying the provider, as shown in the figure below. The patient is often left with “out of pocket expenses”: that is, the reimbursement often does not match the total expenditure. In this situation, the patient is aware of the total costs and must bear the full economic impact of the health services provided until reimbursement is received from the third-party insurer.

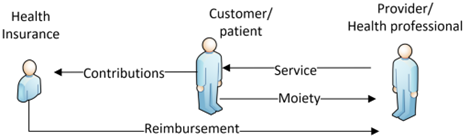

A variation on this arrangement is co-payment, where the health provider can charge the patient’s health fund directly, with the patient only having to pay any shortfall or co-payment. If there is no shortfall or co-payment, then the customer/patient may consider this “bulk billing”. Disability services in Australia, are quoted and accepted by the NDIS, and when services are provided, the bills are forwarded to the NDIA (National Disability Insurance Agency) and payment is made up to the agreed budget.

(created with reference to lecture notes created by Legge, 2015)

Direct payments to the provider establishes the possibility for negotiation between the health insurance organisation and the provider regarding agreed levels of remuneration through a divested health remuneration model, as shown in the below figure. In this arrangement, the provider remains free to determine the charges sought for the service; however, there is now a weak mechanism through which costs may be negotiated, and the customer or patient is no longer a cost “acceptor”. A government may choose to adapt this model to achieve divested universal health coverage. The attractiveness is that this preserves existing funding institutions (private health insurance) and mechanisms. The government may also ensure the economic viability of such a system by requiring the participating health insurance funds to contribute towards a centralised pool as a form of reinsurance.

(created with reference to lecture notes created by Legge, 2015)

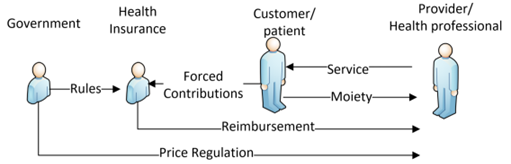

A further development is where a government takes over the responsibility of funding of health services directly through a centralised health payer model, as shown in the figure below. In this case, the government can influence the payments made for health services on behalf of the patient. Universal healthcare occurs where most of a population’s health needs are funded from a centralised revenue pool. The provision of health in the “public system” may appear to be “free” from the consumer’s perspective, especially if few fees or user co-payments (moieties) are avoided. In the case of bulk billing, there may not be a patient payment or co-payment.

(created with reference to lecture notes created by Legge, 2015)

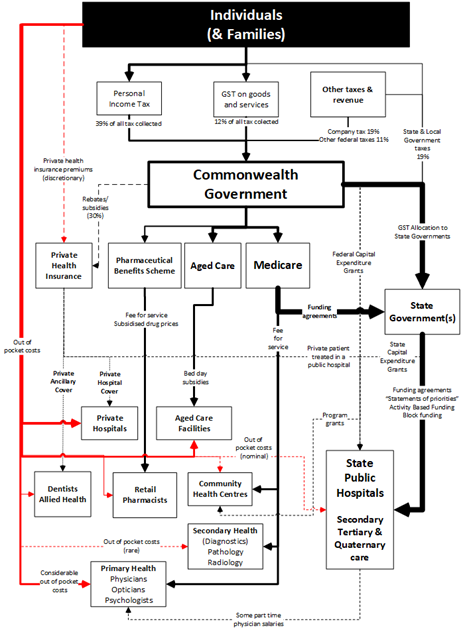

A further complication if a health system is vast is that additional funding pathways will be required as services and stakeholders are added. For example, the current funding pathways in Australia are complex, as shown in the figure below.

Since Federation, taxation in Australia become progressively centralised, enabling the Federal Government to influence areas outside its constitutional boundaries using funding as a lever in place of statutory legislation. Notably, the provision of public health services remains a state responsibility; however, because the Federal Government controls taxation in general and the grants for operating the health systems via Medicare, it can influence policy decisions with respect to the provision of “free” public health services. To date, this influence has been focused on the population’s access to health services, regardless of the ability to pay or location. The mechanism for this has been the Healthcare Agreements with activity based funding (ABF) included as a funding reform. The current arrangements of a comprehensive public hospital system supplemented by private hospitals with access managed by general practitioners have arisen due to fierce political debate. The focus of health provision differs across the levels of government in Australia.

Responsibility for the delivery of hospitals remains a state responsibility; however, the Federal Government has increasingly acted to consolidate and harmonise the delivery of health via funding mechanisms.

The table below provides examples of a fragmented health care system and lists the principal roles of each level of government.

Principal responsibilities

| Level of Government | Principal Role in Health | Examples |

| Commonwealth Government | Policy harmonisation | Australian Health Practitioner Regulation Agency |

| Funding | Medicare

Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme Aged Care National Disability Insurance Scheme |

|

| State Government | Regulation and funding agreements | Public Hospitals Funding Agreements

Community Health Services |

| Services | Public Hospitals

Aged Care centres Water and sewerage |

|

| Local Government | Regulation | Bylaws |

| Services | Sanitation (garbage collection) |

How are funds for health services distributed?

Health service funding should encourage the allocation of resources based on population and clinical needs so that care and treatment occurs at the appropriate time. Ideally, remuneration methods should ensure that services are patient focussed and that there is equity of access. Equity of access means that patients’ health needs are treated similarly (horizontal equity), and those with the greatest/immediate need are treated first (vertical equity.

Various methods are commonly used for funding health services, and are often used in combination to meet differing needs.

Fee-for-service

Fee-for-service is when a health provider is paid an agreed or negotiated amount for a discrete service provided. The provision of primary and secondary health services for non-admitted patients is commonly remunerated using a fee-for-service model. The Commonwealth Medical Benefits Schedule contains a list of fee-for-service care that Medicare will fund provided by medical practitioners and other primary health providers, such as optometrists, nurse practitioners, and many practitioners connected to chronic healthcare. Outpatient pathology and radiology are also funded on a fee for service basis. Practitioners are free to charge patients more than the scheduled rebate, and co-payments are common. Dental services are fee-for-service and not subsidised by Medicare. A fee-for-service model via a single payer scheme such as Medicare can create a wealth of reliable health information for planning and monitoring purposes. Other advantages include transparency, funding levels can be closely related to costs, and that they are simple to operate and discourage underservicing. The disadvantages of this funding model are that financial risks lie with the funding source, and patient overservicing is possible, although patient co-payments restrict this to some extent (Biggs, 2014).

A major feature of the National Disability Insurance Scheme is that funds are made available to people living with a disability for services that they deem give their lives meaning. The disadvantage of this system is the relatively weak capacity for price negotiation and or competition by providers.

Per diem payments

Per diem “per day” funding is a mechanism for the remuneration of hospital inpatient care where a hospital is remunerated for each 24-hour period an inpatient occupies a bed. In some respects, it is similar to a fee-for-service model, where a period of time replaces the service; the key measurement is length of stay. The major advantage of this mechanism is its simplicity; the daily fee remains fixed regardless of the actual costs incurred. Per diem payments create a perverse incentive to keep patients admitted longer than necessary to maximise income. To address this, a tiered fee arrangement can be used, where the daily fee reduces after a number of days. The major disadvantage is that this may not recognise complexity, it rewards inefficiency, and does not encourage quality of care. Per diem payments have progressively been replaced by activity-based funding models, but may still be used to remunerate smaller private hospitals, or where there is a clinical reason to supplement activity-based funding models for a complex admission. (Duckett & Willcox, 2015, pp. 248-250; Willcox, 2005). Until 2023, per diem payments were the mainstay of remuneration to the aged care sector; however, a form of graduated activity based remuneration is currently being introduced (Department of Health and Aged Care, 2022).

Block funding

Block funding is where a provider is paid a given amount of money in return for predetermined defined services over a given period. The funding agreement between the funder and provider includes prospective and specific activity targets and requirements expressed in a service agreement between the funder and the provider. Block funding remains a standard mechanism for providers that tend to be smaller and who may lack the volume or throughput to benefit from models such as activity-based funding or those that provide care that is not easily defined into discrete episodes. The major disadvantage of block funding is that it is a prospective funding arrangement; providers are given a budget for availability, that is, the intention to treat patients, rather than for the work achieved. It is therefore challenging for the funder to hold the provider accountable or to increase their technical efficiency.

Block funding has historically been used to fund categories of health-related activities that previously fell outside of an ABF model, such as provision of resources for teaching, training and research in public hospitals, as well as funding outpatient (non-admitted) health services such as mental health (including child and adolescent mental health), home ventilation, home dialysis and other chronic disease management (National Health Funding Body, 2021). Classification systems have been refined to describe outpatient and emergency department services and are now included in ABF models. For people living with a disability, block funding has often been used by fund providers who determined levels of care. With the introduction of the National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS), individuals are provided with individual funding for the services they require, which consumers pay via a fee for service arrangement. The impact of this development on community health services has been profound. Funding, provided annually is now diverted to the consumer, and care plans need to be individually negotiated (Buckmaster & Clark, 2019).

Activity-based funding

Activity-based funding (ABF), also known as case-mix funding, is the primary funding model used in Australia to fund hospital services (Solomon, 2014). This was initially in public hospitals, and is increasingly mirrored by private health insurance companies (Willcox, 2005). ABF was first used in Australia to fund inpatient care including emergency department and outpatient presentations and has progressively been extended to encompass funding for subacute (rehabilitation, palliative and geriatric services) and non-acute care (chronic conditions) using Australian National Subacute and Non-Acute Patient Classifications (Independent Health and Aged Care Pricing Authority, 2023b).

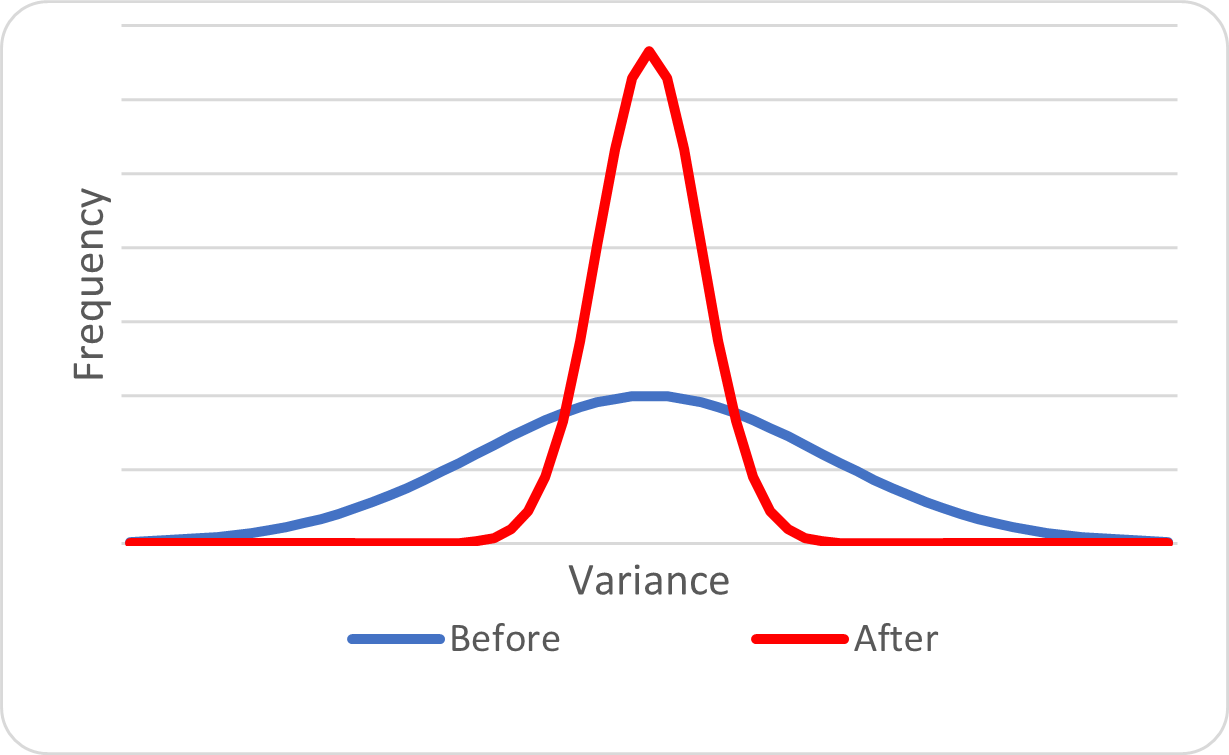

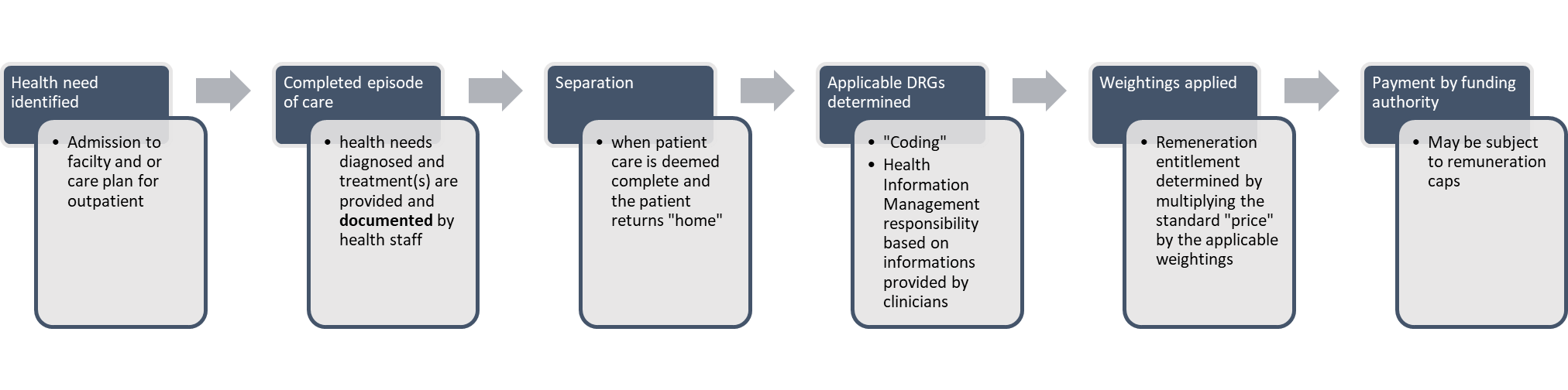

The theoretical principles of activity-based funding are that health services are recognised for the provision of services based on the type of service provided according to the diagnosed needs, where a specified amount is paid on the completion of the treatment, which is adjusted according to the relative complexity and resources required. The aim is to “improve patient access to services and public hospital efficiency through the use of activity based funding based on a national efficient price” (Council Of Australian Governments, 2011, p. 5 (Section 3a)). ABF is intended to provide transparency and equity of funds allocated to providers and incentivises providers to use the funds more efficiently as a form of technical efficiency. It also encourages allocative efficiency through the provision of timely quality of care (Independent Health and Aged Care Pricing Authority, 2023a; Solomon, 2014). ABF is used to encourage hospital providers to reduce variation; with the payment being based on the average costs associated with a particular diagnosis related group, as shown in the figure below.

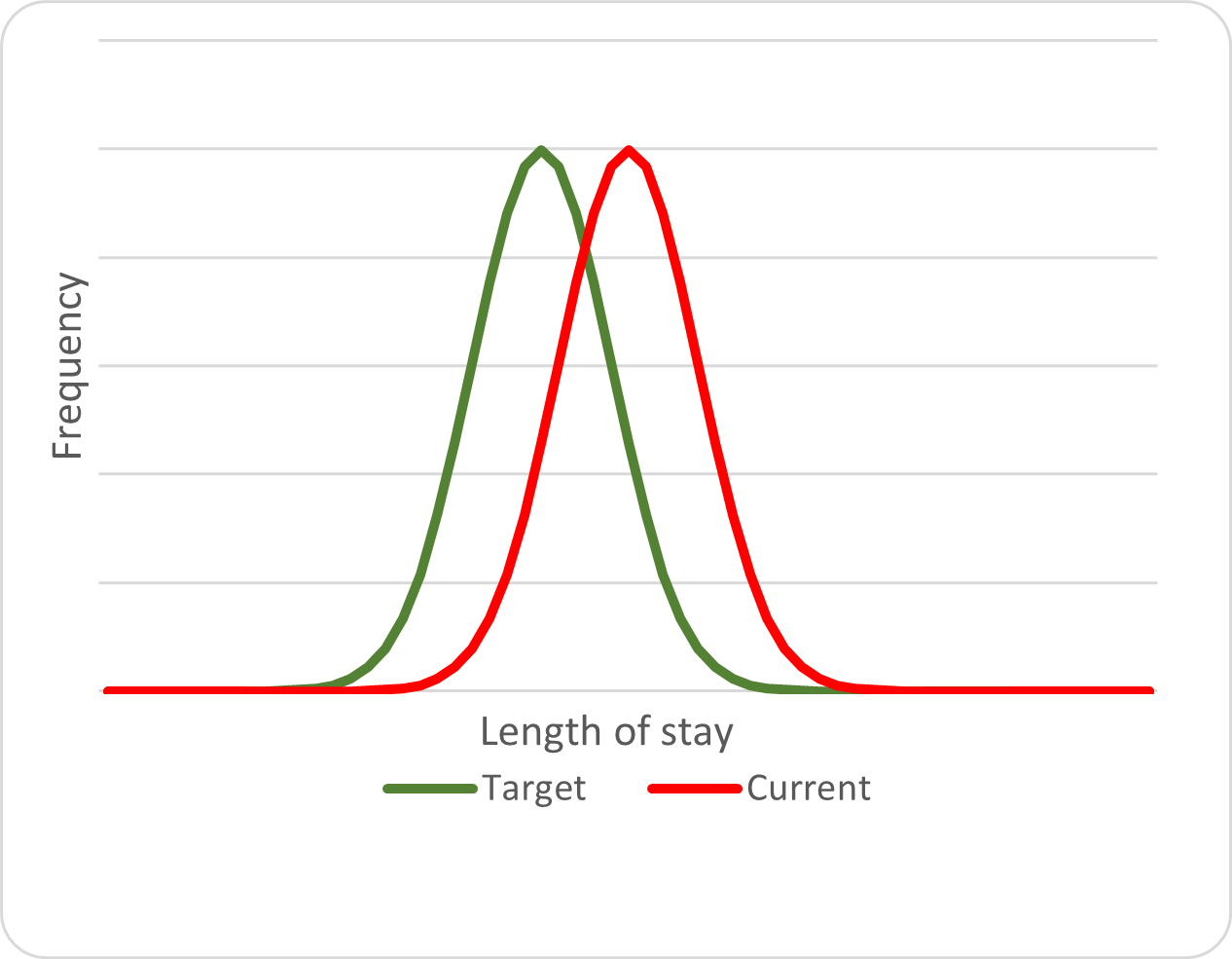

The second imperative is for providers to reduce the costs of care provision. ABF models recognise length of stay as a proxy for cost. If the overall average costs associated with care are lower than the national average, then the hospital will generate a theoretical surplus for that Diagnostic Related Groups (DRG ), as shown in the figure below, and the opposite also applies; if the overall costs are higher than the national average, then the “business” associated with that DRG will operate at a loss. Service agreements at Commonwealth and state levels and state and provider levels are negotiated based on forecasted activity and usually capped. This contrasts with ABF models used in other countries, such as the United States.

The principle of activity-based funding is that healthcare recipients should receive comparable care using similar resources. Ideally, providers would be paid according to outcome (the impact of the care); however, this is complex to quantify. ABF allocates payment based on output (the completion of the care or “separation” of the patient from the provider), with penalties if a patient is readmitted for the same issues within a certain period after separation.

Episodes of care are grouped according to similar diagnosis, procedures and other resource requirements, according to the Australian Refined Diagnostic Related Groups (AR-DRGs). AR-DRG software analyses the diagnoses and treatments and assigns the DRG. Each DRG has a weighting so that all treatments can be compared to one another. A standard remuneration amount is modified according to the weightings associated with the AR-DRG, as shown in the below figure.

The foundation of any ABF system is reliable data. This includes not only aggregated clinical data, but also the costs associated with the provision of care and factors that may influence the delivery of care, for example, the use of intensive care or other high cost services (Edwards, 2015). This may also include clinical issues such as historical demand and comorbidities, environmental issues such as proximity to state capital cities (which influences the capacity to attract specialist clinical staff), and delivery response times associated with medical and other supplies.

DRG systems use data routinely collected by clinicians, with clinical coders analysing this at the hospital level and assigning codes to episodes of care. For example, in Australia, these data then flow through to state health departments and then to the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. In Australia, the management of the AR-DRG and standardised pricing is the responsibility of Independent Health and Aged Care Pricing Authority. As each DRG has a weighting, appropriate episodes of care can be funded using a single price multiplied by the weighting. Using a national price ensures fairness across providers.

Hospital management has autonomy to design and deliver care within a transparent funding and accountability framework, and the funder can determine the overall quantity and quality expectations within the available funds. ABF is dependent upon reliable data, and systems must be in place to understand what services are provided to whom and at what cost across many different types of hospitals and services ( National Health and Hospitals Reform Commission. 2009).

Activity

Type

Watch this video on Activity Based Funding and reflect on the different ways that healthcare can be funded and how it works in Australia (IHACPA, 2021).

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4MvZcrqgK7U

AND

Watch this video on the link between medical records and ABF (IHACPA, 2017).

Capitation

Capitation is a method whereby a health provider is paid a regular fee based on a population and its expected health care needs. In theory, this encourages the provider to engage in preventative healthcare, identify effective treatment pathways, and limit unnecessary care and overservicing. The risks of demand management lie with the provider. For example, if an entire health budget was equally distributed according to geography, wide variances would soon become apparent between different regions (i.e. the outback and the inner city. Capitation is uncommon in Australia; however, there are two programs of note. The first is the Indigenous Australians’ Health Programme primary health care funding model, which uses a combination of capitation and activity-based funding. The second is a program for primary health provision by general practitioners, the Voluntary Patient Enrolment Program (AIHW, 2020, p. 175).

Governance in healthcare

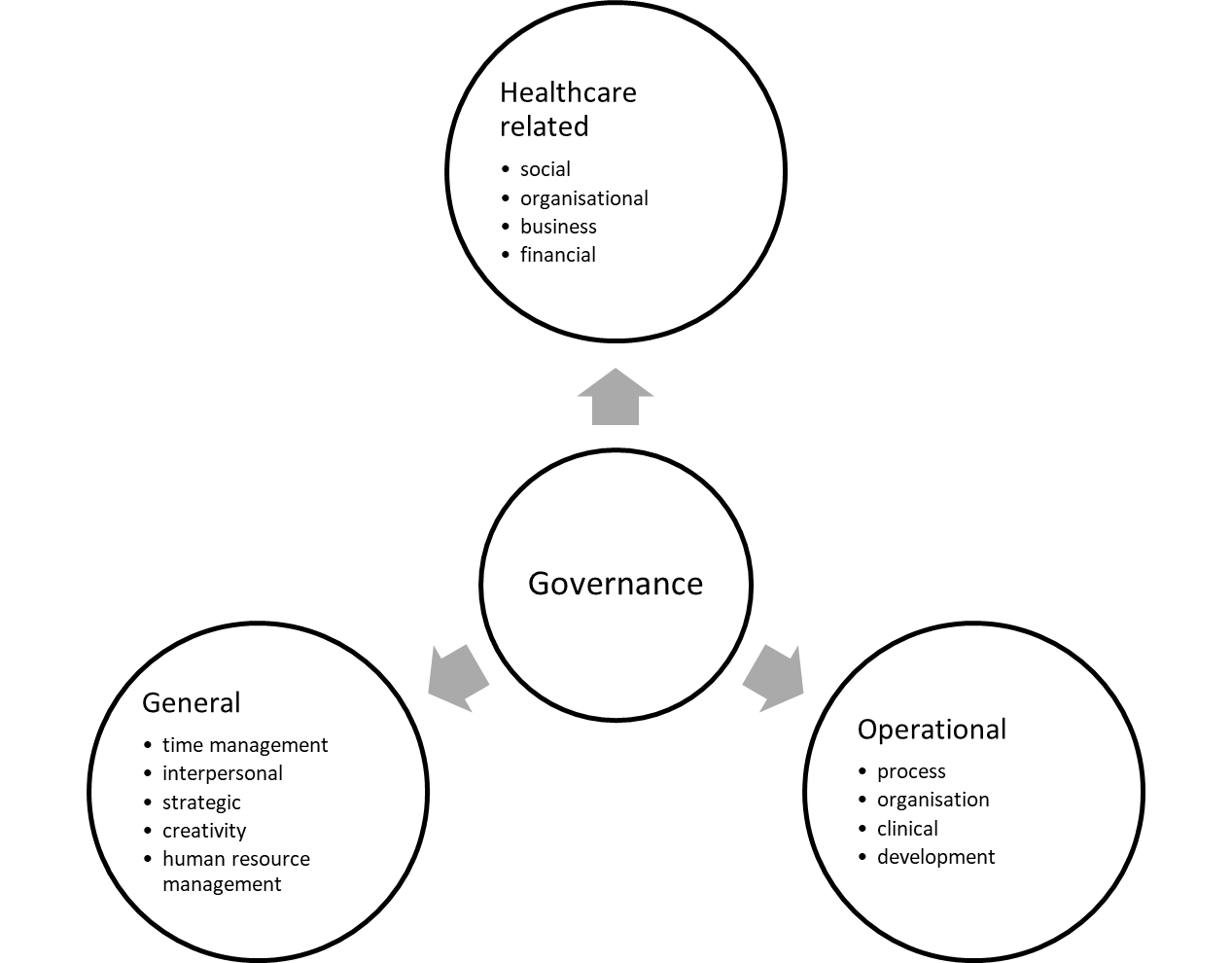

Health and social care organisations require leadership. Specific competencies can be categorised as health related, operational, and general (Pihlainen et al., 2016, pp. 101-103), as shown in the figure below. Organisational leadership can be described as having three main functions; shaping future direction by identifying goals and avoiding risks, fostering external relationships, and monitoring the performance of the organisation (Margolin et al., 2006, p. 5). The principal benchmark for hospitals is the extent to which resources are efficiently deployed so that patients’ needs are achieved in a responsive and timely manner to resolve the health issue and, in the case of infectious agents, to prevent the spread of disease (Srimayarti et al., 2021, p. 87).

Healthcare organisational structures can be hierarchical in nature, with the medical and other professions demanding autonomy and resisting external oversight (Braithwaite et al., 2005, p. 4). Understanding the culture and power dynamics in the health and social care relating to professionalism is important, as it can influence the organisation of governance structures.

The role of governments

In Australia, the government is accountable for much of the expenditure on healthcare, funding Medicare, pharmaceuticals, and hospitals. Managers and leaders in publicly funded health and social care organisations are accountable for expenditure. Governments demand accountability to ensure that public resources are achieving quality outcomes.

A board is responsible for the overall governance, management, and strategic direction of the organisation and for delivering performance in accordance with the organisation’s goals and objectives (Australian Institute of Company Directors) . In Australia, Boards have now been established by health services, primary health networks and non-government organisations to provide oversight, direction, accountability for clinical and financial performance, and to meet community needs in the delivery of services.

Bismark et al. (2013, p. 686) found that boards historically focus on the performance of the Chief Executive and the financial status of hospitals. Issues of healthcare quality and safety are often subject to internal regulatory systems, which Braithwaite et al. (2005) argued are insufficient, and that a coordinated national and even international approach is required to achieve a responsive regulatory framework.

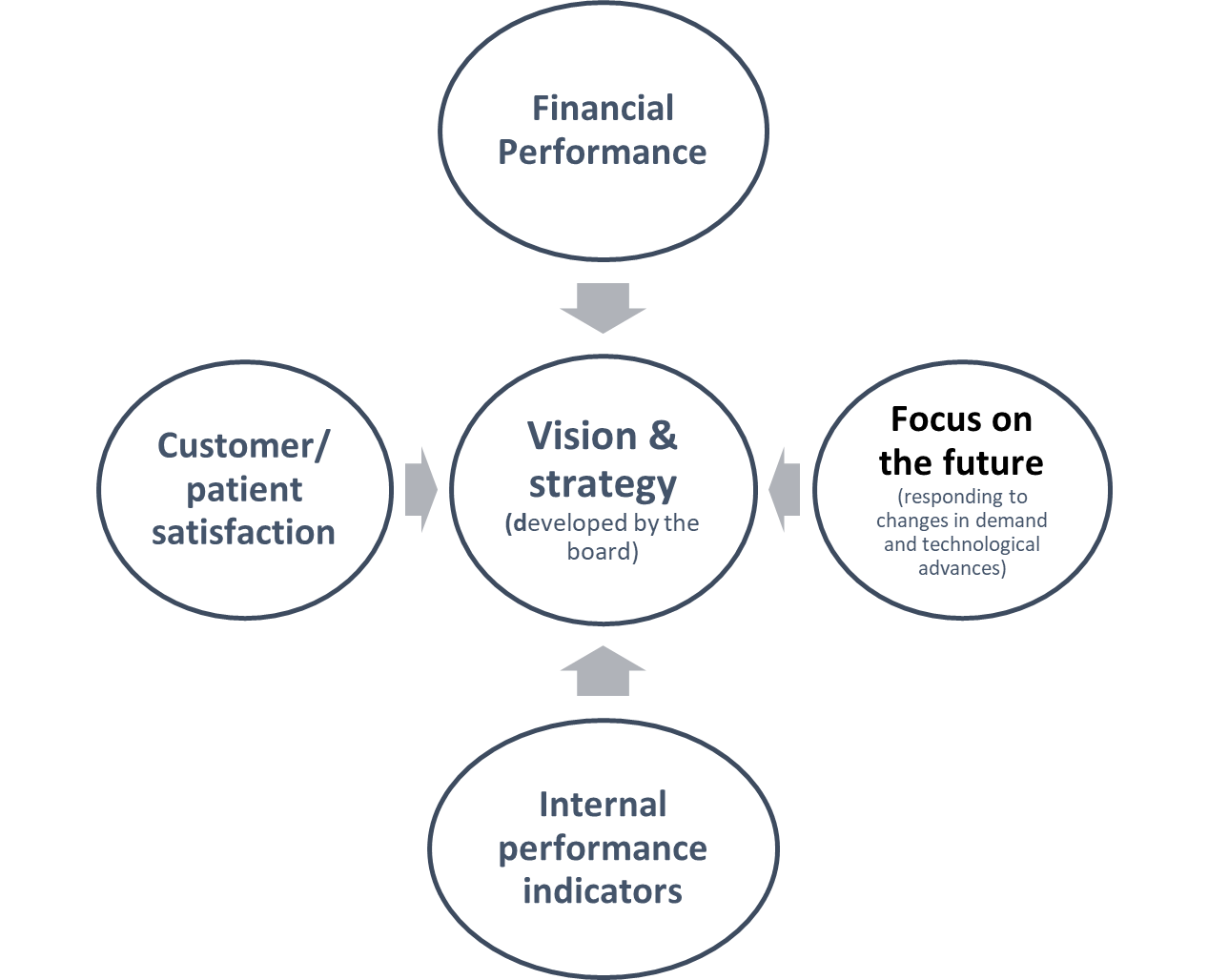

Kaplan and Norton (1992) first identified the need to expand the focus on financial outcomes as a sole organisational performance indicator and include other contributory measures such as consumer satisfaction, the internal processes within the organisation, and the capacity for change and growth. They stressed that there was no single measurement and proposed a reporting format called the balanced scorecard, of which the financial outcomes are a contributory part, as shown in the figure below.

Amer et al. (2022) found that implementation of a balanced scorecard by health care organisations had a positive effect on patient satisfaction and financial performance, but only a limited impact for the satisfaction of healthcare workers. Volatile changes can occur in the financial status of any organisation for any number of reasons, and activities (e.g. increased surgery, pandemic response) in an organisation can have financial impacts, and changes in the factors that affect the non-financial measures are often heralded by changes in the finances.

Budgets

Financial planning, budget development, and implementation are essential for all organisations and should be linked to strategic and operational planning processes. A financial plan enables management to keep abreast of income and expenditure. It is a legal requirement that organisations must remain solvent to continue trading, that is, their total assets must remain greater than their overall liabilities. In general terms income (the addition to the overall asset pool) should exceed expenses (the total liabilities. Should liabilities exceed the available assets, an organisation is insolvent and must cease operating. A technical insolvency is where cashflow into an organisation is temporarily restricted, limiting the organisation’s ability to meet its liabilities.

Budgets are tools that enable health and social care managers to operationalise strategic objectives into realities through resource management, engaging the appropriate number of staff, securing drugs, supplies, etc via procurement strategies, assigning work to match the availability of resources, determining timelines, communicating desired financial targets, and helping motivate staff. From a broader perspective, budgets are critical to assist the organisation to achieve organisational strategy, measure financial performance, plan and facilitate capital expenditure, anticipate operational expenses, plan for provisions, control expenditure, and monitor actual income and expenditure against that which has been anticipated.

Simons (2000, p. 81) conceptualised budget planning as having three interlinked cycles where the initial cycle is concerned with how the organisation generates revenue. This gives rise to how the surpluses or “profit” is managed (whether by paying down debt, increasing reserves and or capital investment), which finally leads to the overall outcome through which the performance of the organisation is measured, and where appropriate, dividends are paid.

The operational management indicators in revenue generation include factors such as the amount of operating cash on hand, the value of both human and non-human resources required to provide the required services, and the resultant revenue after operating expenses are settled. Ideally, the operational activities should generate an overall surplus, and it is an Executive Management responsibility to advise the board regarding the appropriate use of these funds; such as to what extent the surplus should be used to repay debt, or alternatively, invested in new equipment or procedures that could increase return on the value already invested in the organisation. An organisation’s performance can be measured in terms of the organisation’s value using ratios such as owner’s equity, return on equity, and asset utilisation. The best performing organisations in the private sector generate sufficient surpluses to pay down debt, invest in new assets, and also pay a dividend acceptable to the shareholders.

For example, in the publicly funded hospital sector, management is concerned with service delivery, and managing human and non-human resources within a defined budget. Executive Management is responsible for variations in budget and making recommendations to the Board to address surpluses or shortfalls. The Board of Directors and or governing body reviews overall performance. Monthly management financial reports against budget expectations are generated to assist the operations and to encourage optimal performance, culminating in annual financial reports.

Types of Budgets

Finance departments may develop different budgets with varying degrees of input from stakeholders (Birt, 2020; Edwards, 2015).

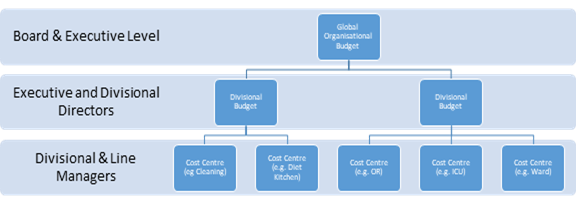

Most managers will be familiar with operating budgets, as these hold accountability for their management. A budget is prepared for each work unit (ward, units, or department) and each of these is assigned a “cost centre”. In practice, cost centre managers are provided with an expense budget that is granular in detail, with staffing as the primary cost. In units where there is a high consumable use in the provision of care, such as the operating suite, intensive care unit and emergency departments, a greater proportion of their budgets will be allocated to consumables.

Divisional budgets can be created by aggregating the individual budgets that contribute to or are a part of the division. For example, surgical wards and the operating theatre will be aggregated to a Division of Surgery budget. The organisational wide or master budget is where the information from all departmental budgets is aggregated and the impact of the organisation’s finances for the reporting period may be reviewed, as shown in the figure below. The global budget is reported to the Board regularly, usually monthly. All anticipated costs and revenues associated with the business are included, such as “services and facilities”, contracts, education/staff development, with the Finance Department, and Executive Management included. The global budget has all the granularity of the individual unit budgets, but is often presented in a summary form. The organisational wide budget forms the basis of the annual profit and loss statement, although the budget amounts are not reported in the formal statement. The figure below shows budget relationships.

Capital budgets describe the organisation’s plans for making investment decisions where a surplus is invested back into the organisation. In publicly owned organisations, major capital expenditure is usually predicated on the availability of capital grants from the government, loans approved by the government, or fundraising appeals to the public, donations, and or bequests from trusts. Major capital improvements are initiatives that will have a useful working life beyond 12 months and are classified as a non-current asset in the balance sheet. Smaller capital expenditure (often under a certain value) will need to be funded from operational revenue and surpluses. In private organisations, capital expenditure is funded from the organisation’s profits, secured loans, raising capital from the owners (shareholders increate their equity or more shares are created to increase working capital) and, less often, through public fundraising.

A cashflow budget is generally managed within the Finance Department, and the information is shared with Senior Management. The purpose of the cashflow budget is to identify and, where possible, predict periods of expected cash shortages. (Birt, 2020, p. 397). Understanding cashflow is necessary because there is often a significant delay in a service being provided and the remuneration associated with that service being received. If payments for services rendered are delayed, there may be insufficient cash available to meet current expenses. Cash flow is the difference between the receipts or amount of cash flowing into an organisation (the revenue) and the disbursements or actual cash flowing out of the organisation (bills, staff payroll etc.). Delays in receipts and the need to meet regular obligations such as payroll can lead to a situation where even the largest of organisations may experience insufficient ready cash to make payments, with short term borrowings or overdrafts becoming necessary. It is a key responsibility of the Chief Financial Officer and their staff to develop and monitor cashflow projections. The performance of actual cash levels against projections serves as a warning device to alert the Finance Department if cash reserves are falling too low. Cash inflows can be increased where payment collection processes can be improved, increasing market share and economic activity, reduction of stock levels, short term borrowings, injection of capital from the owners, or selling underperforming assets. Similarly, cash outflows can be minimised by identifying and cutting expenses associated with waste, duplication of services or inefficiencies, utilising creditor terms (purchasing on credit), moving to “just in time” inventory management and, if necessary, deferring capital expenditure.

An opportunity budget is contained within a business case, which lists the purpose and rationale for the proposed service in detail, as well as the benefits, risks, stakeholders, gap analysis, and a range of alternatives with the reasons why they should be rejected in favour of the desired or proposed project/program. Opportunity budgets are speculative and exist for a particular purpose in anticipation of funds becoming available for use.

Project budgets are the financial plans associated with supporting a project. A project is a unique, time limited activity with a specific purpose to meet a need that is not part of usual operations. In organisations, projects are often used as change management tools to assist an organisation to achieve strategic goals. The major difference between a project budget and an opportunity budget is that funds have been approved and set aside to finance the project.

Budget Approaches

The critical issue for any organisation planning a budget is to understand the market in which it operates. Fortunately, the health sector is relatively more stable and conservative than more volatile markets; however, in principle, the development of an organisational budget relies on three factors:

- understanding the market in which it operates in terms of size and potential for growth,

- the market share (or in the case of health, the likely local demand), and

- the opportunities for strategic development.

In addition, the organisation’s funding sources and revenue (in terms of forecasting demand) dictate the capacity to introduce new revenue generating activities and any changes to the remuneration levels must also be considered. Finally, costs associated with providing consumer services, changes to supplier prices, and staffing costs (such as a new enterprise bargain agreement that increases staffing remuneration levels) and other contingencies must be identified and quantified.

Edwards (2015, p. 232) identified five main approaches in developing budgets in hospitals and health services, as outlined below.

The global budgeting approach or “base budget allocation”, is common when health organisations are funded in block grants; management then divides or allocates funds to the various departments or cost centres. This method of budgeting is still commonly used in community health services, although activity-based funding is prominent in the acute sector. Government departments will often increase their allocations by a percentage rate each year, and the provision of funds will be tied to performance expectations. The advantage of this method is simplicity, opportunity for cost containment, and elimination of unnecessary services (Dredge, 2004, p. 3); however, the disadvantage is that the levers to encourage quality of care are lacking. Internal power relationships within organisations can influence internal funding decisions; thus, allocations may not necessarily be directed to meet customer needs.

Historical budgeting (also known as static, fixed, or forecast) is used when the expected income and expenses will remain relatively constant and are relatively simple to achieve. A disadvantage is that historical budgeting stifles change and development; there is no incentive for organisations to improve quality or to avoid large deficits. “Historical budgeting is designed to maintain the status quo” (Edwards, 2015, p. 232), and as such, has fallen out of favour in the funding of health services.

Flexible budgeting is used when there may be seasonal variations in demand or other fluctuations. This type of budget approach is far more common in private hospitals, where bed occupancy and operating theatre demands can change. For example, surgery demand often decreases significantly over holiday periods if large numbers of medical staff decide to take time off for family purposes (Edwards, 2015).

Zero based budgeting is used to construct a budget completely from the start. This is an extremely involved process for organisations, but may be used to periodically “reset” their historical budgets. Conversely, zero based budgets are used for the development of opportunity and project budgets for purposes that are speculative and without previous activity within the organisation (Edwards, 2015).

Activity based budgeting is used to determine the costs associated with the provision of a particular range of services associated with their respective diagnosis groups and was described earlier in this chapter in more detail (Edwards, 2015).

Health services use a variety of these techniques as appropriate.

Financial Reports

Budget outcomes need to be reported for organisational management. There are two main categories of financial reports: formal reports and management reports.

Formal Financial Reports

Formal reports document an organisation’s economic outcome and describe performance in terms of the change from one reporting period to another. Formal reports do not include budget information or performance against anticipated economic activity. Formal reports are subject to strict auditing requirements, and often take up months to prepare, review, approve, audit, and publish.

The International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) determine the structures and formats of formal financial reports. The benefit of this is that financial statements for any health service, hospital or community health centre can be compared to any other country or industry that has adopted IFRS. The Australian Accounting Standards Board gives equivalence with the IFRS the force of law in accordance with S334 of the Corporations Act 2001 (Australian Government 2001). The Act requires that every organisation subject to the provisions of the Act must provide a formal set of reports at least twice a year. There are three fundamental standard reports, each of which follow a strictly prescribed structure as defined by the IFRS (as adopted by each nation).

The balance sheet (also known as a statement of financial position) explains the value of a company or organisation at a given point in time and always states a particular date, never a period. It lists an organisation’s assets (what they own and control), liabilities (what they owe) and equity (the actual worth of the organisation. The balance sheet is prepared on an accrual basis — it reports on the organisation’s value at a specific time, regardless of whether the organisation has paid the bills or received the remuneration owed to it. A balance sheet describes three main components: assets, liabilities, and equity. Current assets are listed in the order in which they may be redeemed as cash.

The key terms found in a balance sheet are listed in the below table.

Terms listed in a balance sheet

Source: (Birt et al., 2012, pp. 21-22; Edwards, 2015, p. 231)

| Term | Formal definition | Examples |

| Asset | Possessions (and skills) that are owned and have value that can be used to generate income in the future | Earnings and savings (money)

Things that you own that can be sold if needed House or dwelling that you own |

| Current assets | Assets that are either cash or items that can be easily and quickly converted to cash (sold) | Cash Short-term (+/− long-term) investments Accounts receivable (monies you are owed) Inventory Prepaid expenses |

| Non-current assets | Non-current assets are items of value but are either not able to be or expected to be converted to cash in the short term | Long-term investments (full value) Plant and equipment Real estate Patent rights Trademarks |

| Liability | Most commonly, items of value owed to other people or organisations for which a payment or trade is required | Bills waiting to be paid Rent Mortgage payments |

| Current liabilities | Obligations that need to be paid in the short term within the current reporting cycle | Accounts payable Loan repayments Dividends to shareholders Income tax payable Rent (i.e. year 1 of a three-year lease) Sinking funds Contributions to capital reserves |

| Non-current liabilities | Payments that the organisation is obligated to pay in the future but not in the next immediate reporting phase, these are sometimes known as fixed liabilities | Loan repayments after the next year

Lease payments beyond the next reporting period (i.e. if a lease is taken out for three years, the lease payments required for years 2 and 3) |

| Equity | The monetary value of an organisation after all liabilities are paid. Owner’s equity is the amount of money the business owes the owners. | A house is valued at $810K (asset) but has a mortgage (liability) of $450K, so the equity (residual economic value) to the owner is $360K: in other words, the owner has 44% equity (ownership) in the property, the bank has 55% equity |

The profit and loss statement (also known as income statement or statement of financial performance or revenue statement) is perhaps the most intuitive report to read, and always refers to a period of time; for example, an annual report will explicitly state a period of time ending at a particular date, such as For the Financial Year ended 30 June 20XX. The report has two main sections: income (revenue flowing in) and expenses (staffing costs, supplies and expenses, and depreciation of plant and equipment) incurred in providing the services, and these will indicate whether a surplus or a loss has been generated from the operating activities (core business) as the net operating balance. Any losses or gains from investing or financing activities are then listed (derived from the cash flow statement) to provide a net result for the year. Any other comprehensive changes are then listed, which then provides a comprehensive result for the year. The profit and loss statement may include a line for depreciation expenses that refers to the manner in which the cost of valuable assets are “charged” to the organisation over their useful working life.

The cash flow statement (also known as a statement of cash flows) reports on the money that the organisation has received and spent over a given period in accordance with how it has been generated or expended. Health and social care organisations may generate cash from operating activities, such as the provision of health services. However, when an organisation uses surplus funds to buy new assets or sells assets to cover a loss these are termed investing activities. Monies generated from borrowing or paying back loans are referred to as financing activities.

Management reports

In contrast to formal reports, management reports are not defined by IFRS, and vary according to the needs of the managers within an organisation. They often resemble profit and loss statements, with economic activity compared to the anticipated budget amount for that period and variances, as well as a progress amount against planned activity in terms of year to date and variances. It is also helpful to include the previous year’s year to date information.

Rationale for standardised reports

The benefit o f having standardised reports is that the information can be read in terms of horizontal analysis (the change from one reporting period to another) as well as vertical analysis (the proportion each element against the sum. In addition, several standardised ratio analyses can be applied to compare an organisation’s performance against any organisation that uses IRFS reporting.

Managers are expected to control costs listed within their budgets, act if unexpected adverse variances (overspending) may occur, or be prepared to justify (defend) their reasons using evidence-based decision making. To a new or inexperienced manager, an overspend on a management report may appear confronting; however, there are often very good reasons for this to occur; for example, overspending maybe due to increased activity or purchasing. Overspending is viewed with concern if there is no corresponding increase in activity, income, or explanation.

Key Takeaways

The relationship between finance, financial management, and healthcare provision is complex and dependent upon political choices that shape policy decisions made according to the human, economic, and geographical resources historically available to the government considering the cultural values of the population.

Regardless of the choices made, the reduction of activity to financial terms alone is both relatively easy given the art and science of accounting, but perilous if the quality and impact of the health service outcomes are not considered. Managers in health and social care in the 21st century are expected to be able to read cost centre reports. Leaders must have a strong grasp and understanding of financial reporting and governance practices. Professional financial staff are key partners in effective healthcare delivery.

References

References

Alemayehu, B., and Warner, K. E. 2004. The lifetime distribution of health care costs. Health Serv Res, 39(3), 627-642. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6773.2004.00248.x

Amer, F., Hammoud, S., Khatatbeh, H., Lohner, S., Boncz, I., and Endrei, D. 2022. The deployment of balanced scorecard in health care organizations: is it beneficial? A systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res, 22(1), 65. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-021-07452-7

Australian Government 2001), Corporations Act https://www.legislation.gov.au/Details/C2019C00216 4/9/2023

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. 2021. Understanding welfare and wellbeing. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Retrieved 25 June from https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/australias-welfare/understanding-welfare-and-wellbeing

Australian Institute of Company Directors https://www.aicd.com.au/ 4/9/2023

Biggs, A. (2014). Evidence around GP co-payments and over servicing. Commonwealth of Australia. Retrieved 14 September from https://www.aph.gov.au/About_Parliament/Parliamentary_Departments/Parliamentary_Library/FlagPost/2014/February/GP-copayment_overservicing 4/9/2023

Birt, J. 2020. Accounting : business reporting for decision making (Seventh edition. ed. Milton, QLD: John Wiley and Sons Australia, Ltd.

Birt, J., Chalmers, K., Byrne, S., Brooks, A., and Oliver, J. 2012. Accounting: Business Reporting for Decision Making (4th ed.). John Wiley and Sons Australia.

Bismark, M. M., Walter, S. J., and Studdert, D. M. 2013. The role of boards in clinical governance: activities and attitudes among members of public health service boards in Victoria. Australian Health Review, 37(5), 682-687. https://doi.org/Doi 10.1071/Ah13125

Braithwaite, J., Healy, J., and Dwan, K. 2005. The governance of health safety and quality. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia.

Buckmaster, L., and Clark, S. 2019. The National Disability Insurance Scheme: a quick guide-May 2019 update.

Collier, R. (2008). Activity-based hospital funding: boon or boondoggle? CMAJ, 178(11), 1407-1408. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.080594

Collyer, F., and White, K. 2001. Corporate Control of Healthcare in Australia. Discussion paper 42. Retrieved 12/08/2021, from australiainstitute.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/DP42_8.pdf

Council Of Australian Governments. 2011. National Health Reform Agreement. Canberra: COAG. https://federalfinancialrelations.gov.au/sites/federalfinancialrelations.gov.au/files/2021-08/national-agreement.pdf

Courtney, M. D., and Briggs, D. 2004. Health care financial management. Marrickville: Elsevier Australia.

Department of Health and Aged Care. 2022. Australian National Aged Care Classification (AN-ACC) Funding Guide.

Dredge, R. 2004. Hospital Global Budgeting (Health, Nutrition and Population [HNP]) Discussion Paper, Issue. W. Bank. www.who.int/management/facility/hospital/Hospital%20Global%20Bugeting.pdf

Duckett, S. J., and Willcox, S. 2015. The Australian health care system (5th ed.. ed.. South Melbourne, Vic. : Oxford University Press.

Edwards, I. 2015. Financial Management. In G. E. Day and S. G. Leggat (Eds.), Leading and Managing Health Services: An Australiasian perspective (pp. 230-244). Cambridge University Press.

Independent Health and Aged Care Pricing Authority. 2023a. Activity based funding. https://www.ihacpa.gov.au/health-care/pricing/national-efficient-price-determination/activity-based-funding

Independent Health and Aged Care Pricing Authority. 2023b. Subacute and non-acute care. https://www.ihacpa.gov.au/health-care/classification/subacute-and-non-acute-care

International Labour Organization. 2023. International Labour Standards on Social Security. United Nations: International Labour Organisation.

Kaplan, R. S., and Norton, D. P. 1992. The Balanced Scorecard – Measures That Drive Performance. Harvard Business Review, 70(1), 71-79. <Go to ISI>://WOS:A1992GY39500008

Kutzin, J., Witter, S., Jowett, M., and Bayarsaikhan, D. 2017. Developing a national health financing strategy: a reference guide. In Health Financing Guidance (pp. 37). Switzerland: World Health Organization.

Legge, D. G. 2015. Health Systems Development: A Policy Guide. 122. www.davidglegge.me/sites/default/files/Legge%282015%29CHPHealthSystemsDevelopmentPolicyGuide.pdf

Li, Y., Wu, Q., Liu, C., Kang, Z., Xie, X., Yin, H., Jiao, M., Liu, G., Hao, Y., and Ning, N. 2014. Catastrophic Health Expenditure and Rural Household Impoverishment in China: What Role Does the New Cooperative Health Insurance Scheme Play? PLoS One, 9(4). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0093253

Lo Sasso, A. T., and Lurie, I. Z. 2009. Community rating and the market for private non-group health insurance. Journal of Public Economics, 93(1), 264-279. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2008.07.001

Margolin, F. S., Hawkins, S., Alexander, J. A., and Prybil, L. 2006. Hospital governance: initial summary report of 2005 survey of CEOs and board chairs. Chicago: Health Research and Educational Trust.

Meerding, W. J., Bonneux, L., Polder, J. J., Koopmanschap, M. A., and van der Maas, P. J. (1998. Demographic and epidemiological determinants of healthcare costs in Netherlands: cost of illness study. BMJ (Clinical research ed.), 317(7151), 111-115. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.317.7151.111

National Health Funding Body. 2021. Funding Types. National Health Funding Body Retrieved 20 Sept from https://www.publichospitalfunding.gov.au/public-hospital-funding/funding-types

National Health and Hospitals Reform Commission. 2009 A healthier future for all Australians: final report June 2009. http://www.nhhrc.org.au/internet/

nhhrc/publishing.nsf/Content/nhhrc-report (accessed Aug 2009)

Pihlainen, V., Kivinen, T., and Lammintakanen, J. 2016. Management and leadership competence in hospitals: a systematic literature review. Leadersh Health Serv (Bradf Engl), 29(1), 95-110. https://doi.org/10.1108/LHS-11-2014-0072

Shan, L., Li, Y., Ding, D., Wu, Q., Liu, C., Jiao, M., Hao, Y., Han, Y., Gao, L., Hao, J., Wang, L., Xu, W., and Ren, J. 2016. Patient Satisfaction with Hospital Inpatient Care: Effects of Trust, Medical Insurance and Perceived Quality of Care. PLoS One, 11(10), e0164366. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0164366

Simons, R. 2000. Performance measurement and control systems for implementing strategy : text and cases. Upper Saddle River, N.J. : Prentice Hall.

Solomon, S. 2014. Health reform and activity-based funding. Med J Aust, 200(10), 564. https://doi.org/10.5694/mja14.00292

Srimayarti, B. N., Leonard, D., and Yasli, D. Z. 2021. Determinants of Health Service Efficiency in Hospital: A Systematic Review. International Journal of Engineering, Science and Information Technology, 1(3), 87-91.

West, B. (1992. Theatre Nursing: Technique and Care (6th ed.. Bailliere Tindall.

Willcox, S. 2005. Buying best value health care: Evolution of purchasing among Australian private health insurers. Aust New Zealand Health Policy, 2(1).