Organisation and governance

Digital Health – Leading innovation in healthcare through digital health technologies

Digital Health - Leading innovation in healthcare through digital health technologies

Sheree Lloyd and Janelle Craig

Introduction

This chapter is important to health service leaders because innovative technologies have a significant impact on healthcare service delivery. While the impact of these technologies is disruptive, they create opportunities for a better experience when accessing healthcare, as well as achieving improved health outcomes for patients, consumers of health and social care services, their carers, and the community more broadly. In this chapter, you will learn how digital health technologies can improve health, the foundations that underpin and enable their use, and how the health service leader can be the catalyst for digital innovation through investment, supporting technology adoption, and realising the benefits of digitally enabled health care.

“Innovation is driven by the need to deliver new, more, better, and seamless health services and prepare for future crises with less funds, while addressing long-standing inequities” (World Bank, 2023).

Digital Health and the Role of Health Technologies

There are many published definitions of digital health. The breadth of definitions demonstrates that the impact of technology is broad, and the perspectives on what digital health means are diverse. The table below provides an overview of some of the definitions for digital health used around the world.

Global Definitions for Digital Health

| Definition of Digital Health | Organisation |

| The application of technology to improve the health of populations. | World Health Organization (2021) |

| Using technology to improve the healthcare system for providers and patients alike | Australian Government and Department of Health and Aged Care (2022) |

| The use of digital technologies and accessible data, and the associated cultural change it induces, to help New Zealanders manage their health and wellbeing and transform the nature of health care delivery.

|

New Zealand Ministry of Health (2022) |

| Digital health includes diverse categories of products comprising telehealth and telemedicine, mobile health, wearable devices, health information technologies and personalised medicine.

It refers to the usage of connected devices, wearables, software including mobile applications (apps) and artificial intelligence (AI) to address various health needs via information and communications technologies.

|

Singapore Health Sciences Authority, Singapore Government (2022) |

| The mobile apps and software that support the clinical decisions doctors make every day to artificial intelligence and machine learning, and how digital technology is driving a revolution in health | United States and the Food and Drug Administration (2020)

|

| The tools and services that use information and communication technologies (ICTs) to improve prevention, diagnosis, treatment, monitoring and management of health-related issues and to monitor and manage lifestyle-habits that impact health. | European Commission (2018) |

| The cultural transformation of how disruptive technologies that provide digital and objective data accessible to both caregivers and patients leads to an equal level doctor-patient relationship with shared decision making and the democratization of care (Medical Futurist, 2021) | Medical Futurist (2021) |

| Using technology to help health and care professionals communicate better and enable people to access care they need quickly and easily, when it suits them | National Health System England (2019). |

While the execution may be different, for health leaders to action the transformative potential of digitally enabled healthcare, the following domains of action must be present, as these underpin the effective use of technology for enhanced decision-making and a thriving health and social care system. By integrating digital technologies, health leaders can offer services in different ways, engage individuals in managing their own health, and redesign health systems and services differently to the way in which consumers, carers, health leaders, and clinicians currently experience them.

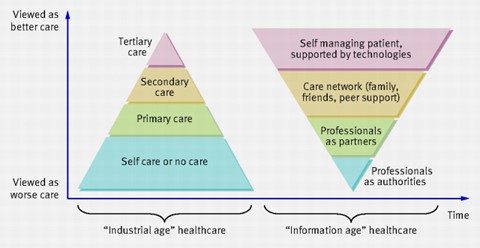

It is now recognised that, for the future, a major shift is required from disease focused models of care to support informed, self-managing patients who actively direct their own health care (Greenhalgh et al., 2010). New models of care can be enabled through electronic health care records (longitudinal summaries) extracted from electronic medical records (organisational records) that link to personally held records that are shared with treating clinicians to maintain continuity of care (Greenhalgh et al., 2010). The diagram below from Greenhalgh et al. (2010) illustrates the impact of this shift, showing that it creates information parity between patients and health providers as it puts health information directly into the hands of individuals. With this ability to hold personal health information, individuals can now take a more active role in their health care. This also means a change in the role of health providers from authorities of care to partners and facilitators of care (Greenhalgh et al., 2010). An example of this might be when a chronic disease is diagnosed, the recipient of the diagnosis would be referred to a specialist team who would provide education, management tools for their condition, and monitoring devices. Regular monitoring and alerts would flag with consumers and healthcare professionals when intervention was required. Consumers and clinicians are empowered through information and digital health tools.

This chapter concentrates on the focal points for health leaders wanting to progress a digital health agenda. The aim of digital transformation is to improve health outcomes for the population using digital health technologies, solutions, and trusted and reliable data and information. Consequently, the chapter is organised around the broad topics of foundations and the digital ecosystem, vision leadership and culture, governance and ethics, workforce, and implementation.

The below figure demonstrates the foci for health leaders to enable digital and social care service delivery.

Foundations and Digital Ecosystem

A solid technical foundation is required to make significant progress in achieving digital transformation. This foundation is comprised of the infrastructure necessary to increase the capacity of health services to benefit from timely access to information, and for health consumers to feel more engaged in their care due to tools such as patient portals, personal health records, and health apps. Among the infrastructure requirements are:

- Appropriate information and communication systems (ICT) and access to high-performing, secure, responsive cloud services to host software and store quanta of data and information.

- Standards and terminologies to support technical interoperability of systems across the health and social care sector to facilitate information sharing.

- Secure repositories for storage and sharing of information to leverage the value of information while safeguarding privacy to mitigate data breaches.

- Connected devices, often described as the internet of things (IoT), and software solutions that meet clinical requirements and support an expanded scope of health service delivery including self-care services.

- Software and hardware solutions that are consumer friendly, usable, affordable and accessible to the consumers of health and social care services.

- High-speed internet connections and bandwidth capacity to support mobile applications, telehealth, and IoT applications.

Collectively, these components work together to create the technical platform for a digital health ecosystem that supports an interoperable infrastructure that can be used by the healthcare community across all care settings and care providers. When health information systems are interoperable data can be shared and the systems can seamlessly ‘talk’ to one another (World Health Organization [WHO], 2021). The components are described as the ‘digital ecosystem’ and should support the secure exchange of health data between providers, health system managers, health data services and consumers (WHO, 2021).

Seamless communication enabled by interoperability across Information Technology (IT) systems and sectors is essential for clinical data to be turned into meaningful information that can be used by health managers for effective decision-making. Data exchange architectures, application interfaces, and standards need to be in situ, as these are the foundation units that support interoperability (Healthcare Information and Management Systems Society, 2022). However, infrastructure alone is insufficient to realise the benefits of digital health. This has been evidenced by many health IT projects in the past that heavily invested in technical equipment and left the change effort largely unsupported (Baghizadeh, Cecez-Kecmanovic and Schlagwein, 2020; Gauld, 2007; Kaplan and Harris-Salamone, 2009). Digital innovation is a step change in the way healthcare is delivered and how consumers interact with the healthcare system. Therefore, in addition to the enabling technical foundations, the below building blocks are required for change for which health leaders must take the lead:

- vision, leadership, and culture;

- governance and ethics;

- workforce;

- implementation.

While over the past 25-30 years great progress has been made and we have witnessed massive technological progress and the availability of data, health policy decisions in many countries are still not based on reliable data (World Bank, 2023). They go onto say that in challenging fiscal environments, people-centered and evidence-based digital investments can help governments save up to 15 percent of health costs (World Bank, 2023). Further, a human-centered, health-data-driven ecosystem is required to tackle the disparate nature of health data (Stevens et al., 2022). Stevens et al. (2022) proposed a model that applies four data quadrants: “administrative and financial, logistics and facility, medical, and paramedical generating data based on four different questions: ‘Who am I?’, ‘Where am I?’, ‘Am I healthy?’, and ‘How do I recover?”.

Vision, Leadership, and Culture

For health and social care services contemplating their digital future, the move to digital ways of working will encompass a range of options, with no universally agreed approach. Having a strong vision for why digital health is needed and how it will positively impact the health of the population, deliver safer care or improve work processes requires a compelling link between the change and the expected benefits. A successful vision for digital health needs to have strong alignment to overall strategy and priorities. The call to action for leaders is for investment in digital health to be aspirational and challenge the status quo and to have this clearly articulated in the vision statement for digital health.

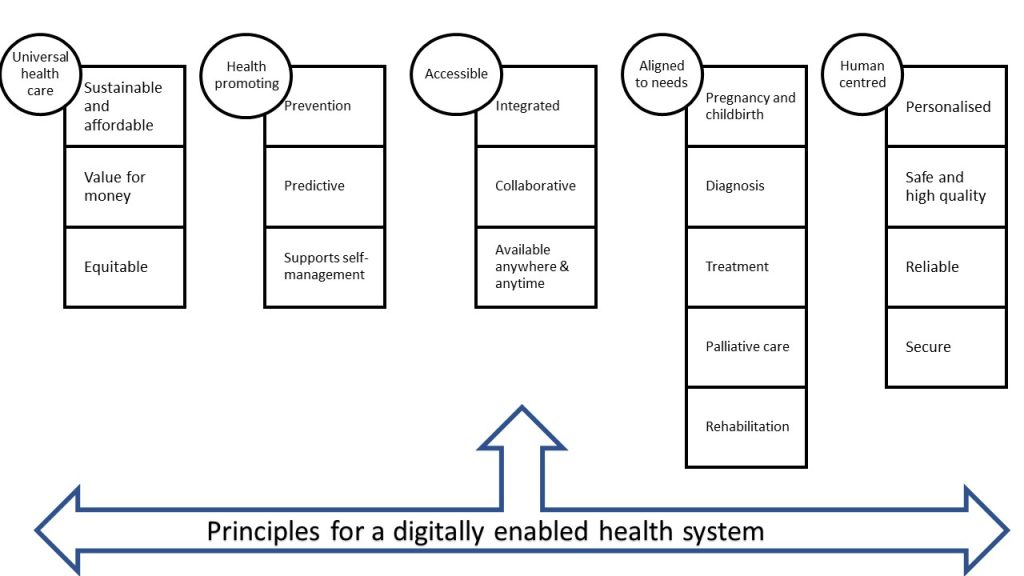

Digital health will be valued and adopted if it aligns with accepted principles for strong healthcare systems that are accessible, universally available, of high quality, safe, sustainable, and that strengthen health promotion, disease prevention, support individuals with care when and where they need it, and from the ‘cradle to grave’ (WHO, 2021). Digital health can contribute to better health outcomes if there is adequate investment in governance, workforce, and organisational capacity to enable the change required for the implementation of digital solutions (WHO, 2021). Leadership, planning, staff development, and training are required because health systems and services are increasingly digitised and vital investments are made in people and processes. Leaders will lay out the vision for the digitisation of the health sector to improve health outcomes through new models for the delivery of services (WHO, 2021). The key principles for a digitally enabled health system are shown in the figure below.

The box below includes examples of vision statements from around the world and demonstrate the emphasis of digital health ambitions.

| Australia

‘Better health for all Australians enabled by seamless, safe, secure digital health services and technologies that provide a range of innovative, easy to use tools for both patients and providers’ (Australian Digital Health Agency, 2018) European Commission Harnessing the potential of data to empower citizens and build a healthier society (Kolitsi et al., 2021) World Health Organization Digital health can help make health systems more efficient and sustainable, enabling them to deliver good quality, affordable and equitable care (WHO, 2021). United States Food and Drug Administration Empower stakeholders to advance health care by fostering responsible and high-quality digital health innovation. USA Digital Health Centre of Excellence (U.S. Food and Drug Administration, 2020). New Zealand Ministry of Health The Vision for Health Technology outlines how we see technology shaping the way New Zealanders ‘live well, stay well and get well’ in 2026 (New Zealand Ministry of Health, 2022). |

The promise of digital health to deliver improved health outcomes, generate efficiencies, and maintain safety and quality requires vision and clear direction through the leaders of health and social care organisations.

Activity

As a leader or manager of a health service(s), what is your vision for health services and therefore, what is your definition of digital health?

Test your vision and definition against a society with many older people. Consider their challenges, their healthcare needs, and how they would prefer to live independently for as long as possible. What digital tools could be most effective to support their health-related quality of life?

Once the vision has been crafted for digital health innovation, health managers must demonstrate leadership through a commitment to their teams and organisation so that positive organisational culture is sustained throughout the change that will accompany the introduction of new technologies and health information systems. Acceptance and readiness to adopt innovation are more likely to be sustained if the digital application makes work easier, more accessible, safer, and delivers better quality. When people understand how technologies will support them, they can feel excited about their future working in health and social care. Not all innovation and technology implementation efforts are successful; thus, there must be a tolerance level for failure and for sharing important lessons without fear of blame and retribution. A culture of innovation has a healthy risk appetite and supports experimentation and learning from failure. Additional insights into the topic of innovation can be found in the Innovation and performance in health and social care organisations chapter. Involvement of all users of digital technologies and consumers in co-design will lead to more optimal and suitable solutions.

Health leaders that communicate clearly, and model and promote the vision for digital health will set the tone for the organisation and its culture. Cultures that support innovation have a strong connection to why change is necessary, and leaders who collaboratively take their people forward into the future. For insights into leadership approaches and styles best suited for significant change such as digital innovation, see the Implementation of Complex Interventions in Health Services chapter.

Investment in Digital Solutions

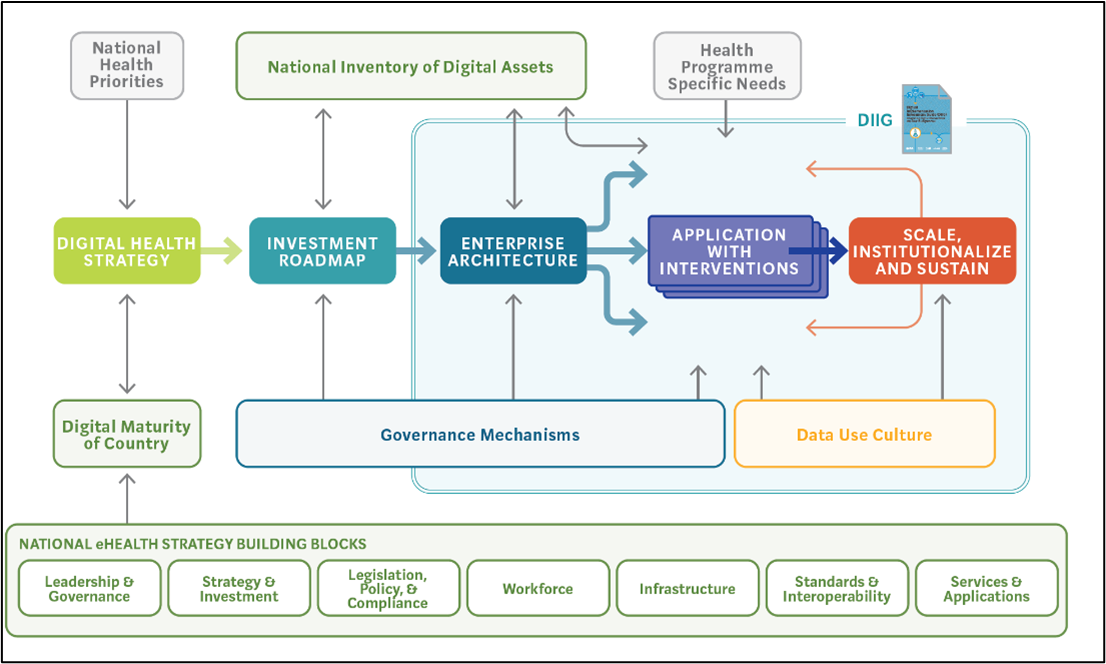

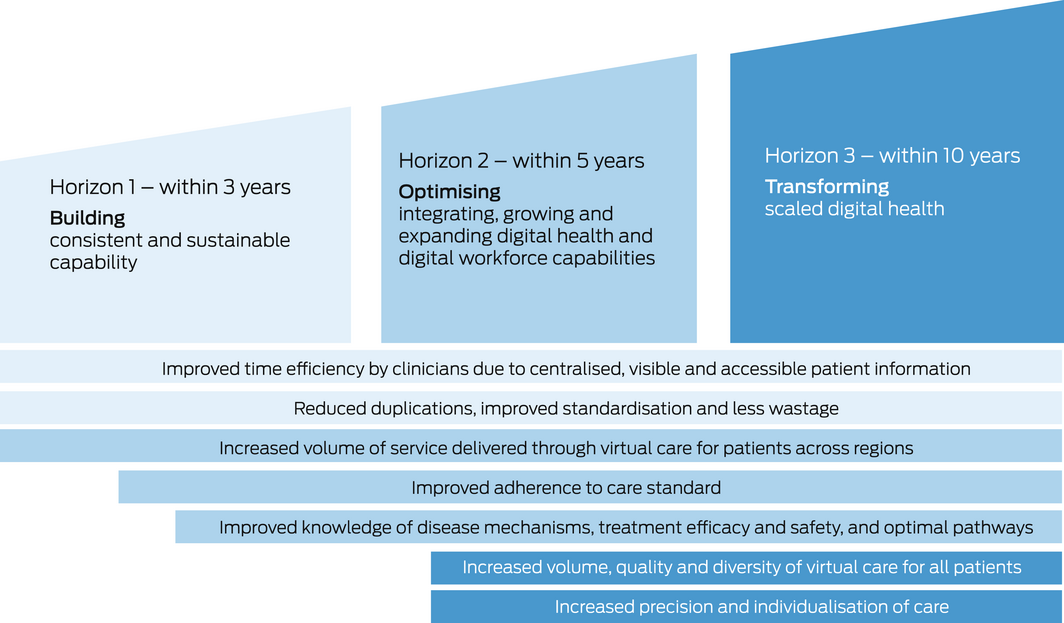

Advanced and emerging economies are facing challenges in ensuring that health and social care is affordable, safe, accessible, sustainable, provide value to their funders and the community, and meet the needs of the community and individuals. So how can we identify technological solutions for ‘better’ health outcomes that impact positively upon the population and individual health? A good place to start is with a known problem or challenge that requires a solution, and examination of all possible solutions, including the role that technology might play. If we wish to achieve and sustain a healthy population, we need to invest in new ways of working and technology can support this. Many challenges are faced by health systems across the world, including a growing burden of chronic disease and aging populations (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2021). According to the WHO, in 2019, chronic conditions caused almost three in four, or 42 million deaths, globally (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2021). Globally, there are challenges to funding digital health solutions, and it is difficult to demonstrate a return on investment using routine economic measurement techniques (Woods et al., 2022). The WHO (2020) stated that progressing digital health is a dynamic process, dependent on the needs and constraints of the country as requirements change over time. However, the building blocks and foundations must be in place, as shown in the figure below. The WHO (2020, 2022, n.d.) has a variety of tools to progress the use of digital health, including frameworks and guidelines to support investment choices and to support the deployment of digital solutions.

Banking, agriculture, retail, and other sectors invest heavily in digital solutions and recognise technology as integral to the achievement of their strategic intentions. These industries have made investments to acquire hardware, software, human resources, and development of digital applications such as online banking, self-service portals, and mobile apps to deliver anywhere, anytime access to services. Sufficient resources are required to protect digital assets and customer data from fraud and theft for all organisations implementing digital technologies and information systems, and safeguarding against data breaches is a strategic priority for all industries. This is particularly relevant in the health industry due to the sensitive and personal nature of data held by health care information systems, apps, and patient records. Many countries, such as Australia, have regulations in place to ensure that data breaches are reported.

Activity

To understand the different ways to measure the benefits of digital health, read the paper by Woods et al. (2022)

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.5694/mja2.51799

Reflect on the proposed alignment of electronic medical record benefits and achievement of the quadruple aims of:

- enhancing the patient experience,

- improving the health of the population,

- reducing per capita costs of hospital services and tertiary care, and

- improving the work life of health providers (Coleman et al., 2016)

Alignment of digital health acquisitions with strategic priorities and having both short- and long-term horizons to realise benefits of information systems, for example, the electronic medical record (EMR) described by Woods et al. (2022), is a realistic and pragmatic approach.

Digital Health Applications in Health, Social and Aged Care Sectors

Digital health can play an integral part in managing the needs of an aging population and the associated increase in chronic diseases (Isakovic et al., 2015). The table below provides a summary of example uses for different types of technologies; however, the possibilities are extensive, and this list is not exhaustive. In the immediate future, self-driving cars, leveraging machine learning, artificial intelligence, and sensors will transport the elderly and poor to appointments. Progress has been made in using robotic technologies to support amputees, clean and deliver supplies in hospitals, and as social companions in aged care settings. Swallowable cameras the size of capsules can take pictures of the intestine and sensor devices can monitor vital signs such as temperature and mobility (Olano, 2019). Hospitals and universities already use simulation tools for education and training. Simulation allows learners to refresh or practice skills in real-time and supports skills development before assessments, interviews, or treatments are attempted on patients using sophisticated mannikins that can be programmed to respond as humans with certain diagnoses. Virtual reality technology has huge potential for medical training and education and for rehabilitation after a stroke or accident, or for therapeutic intervention, such as hip replacement, and other many other applications.

Facilitated by augmented reality, virtual reality, mixed reality, and extended reality – the metaverse is a universal and three-dimensional immersive virtual world (Bansal et al., 2022). Domains for metaverse applications in the healthcare industry include telemedicine, education, clinical care, and physical fitness (Bansal et al., 2022; Thomason, 2021). An example in a paper by Thomason (2021) described a metaverse, where 3D avatars of health workers have spaces to collaborate using tools such as digital whiteboards, and the ability to meet face-to-face without conferencing equipment. In the metaverse, digital twins will detect faults and vulnerabilities in procedures, systems, and machines (Thomason, 2021). Applications for the metaverse include surgical training, anatomy learning, gamified learning, and emergency response training (Bansal et al., 2022; Thomason, 2021).

Digital transformation of the healthcare system is reliant upon interoperability and data sharing. Blockchain and tokens are being used to enable the secure sharing of data and intellectual property (Thomason, 2021). Blockchain is a critical component as it is a sharable, unalterable ledger for tracking assets and recording transactions (IBM, n.d.). Blockchain promotes trust and support for digital identification and verification (Gupta, 2018) characteristics that are extremely important in protecting individuals’ sensitive health data.

Artificial intelligence (AI) is now a mainstream application with huge potential in healthcare to support diagnosis, reduce waste, optimise workforce capacity, improve the reliability of diagnosis, and improve health outcomes (Scott et al., 2021). A simple definition of artificial intelligence is systems that have the ability to mimic human brain function, such as problem-solving and knowledge generation, and importantly, can act as a result of environmental inputs (Lawry, 2020; Russell and Norvig, 2022).

According to Russell and Norvig (2022), the most critical difference between AI and general-purpose software is the ability to act and “take actions”.

Management applications for AI include:

- Communication and support tools – virtual assistants and chatbots in clinics, reception areas.

- Administrative support using process automation – scheduling and optimisation (e.g., theatre and bed usage).

- Identification and flagging of inappropriate utilisation.

- Report writing for routine report writing.

- Automated ICD and other coding.

- Clinical applications for AI.

- Medical image interpretation.

- Decision support for predicting risk of disease, likelihood of response to treatments.

- Rehabilitation support using altered and virtual reality, robots for stroke and other injury.

- Clinical guideline development.

- Estimating dosages for complex drugs (Scott et al., 2021).

Digital transformation has accelerated due to the Internet of Things (IoT). This term is used to refer to the physical devices connected to the internet used as part of our daily lives. Wearable devices, vehicles, medical technologies, and other objects are embedded with software, sensors and electronics that allow these ‘things’ to share and exchange data (NSW Government, 2019). Examples include fleet management, fitness trackers, connected monitoring devices for delivery of care in the home, connected logistics, and resource location; for example, locating assets such as wheelchairs, intravenous pole stands, and other medical/physical aids.

Example applications for digital health by sector

| Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning | Virtual Digital Assistants and Chatbots | Robots | Wearables and Implantables | Information Kiosks and Portals | Mobile Computing and Apps | e-services | |

| Sector | Example applications | ||||||

| Primary care | Billing

Coding Medication management Management plans

|

Information seeking

Triaging |

Self-management and monitoring of chronic disease | Health promotion

and self-management |

Digital prescriptions

Telehealth Behaviour change apps Self-management |

Scheduling appointments

Information seeking |

|

| Hospital | Disease coding

Medication management Medical image interpretation |

Rehabilitation

Triaging |

Rehabilitation

Care assistants Medication delivery |

Diagnosis

Personalised treatment Bionic limbs Bionic vision |

Wayfinding

Health promotion and self-management |

Telehealth

|

Appointments and referrals

Health information and self-management |

| Aged Care | Medication management | Care assistants | Wayfinding | ||||

| Social and Disability Services | Care assistants | ||||||

| Population Health | Predictive planning and forecasting | Not applicable | Personalised medicine | Performance reporting on waiting times

Access Equity |

Surveillance and reporting

Behaviour change (e.g., smoking cessation) |

Health Data and Information Governance

Health information generated by digital health technologies is an organisational asset to be valued throughout the entirety of its lifecycle, from its creation as data through to the destruction or archiving of information. This means due consideration needs to be given to the way health data and information is managed, which requires robust information governance structures to be in place.

Governance is top-down and establishes organisational goals, direction, and limitations, while management is bottom-up and addresses “how to get it done’ (i.e., the oversight of day-to-day operations) (Empel, 2014). Therefore, the information governance structure is an “organisation-wide framework for managing information throughout its lifecycle and supporting the organization’s strategy, operations, regulatory, legal, risk, and environmental requirements” (Empel, 2014, p 30).

There are many information and data governance frameworks in existence that vary in response to industry and business functions. For example, in the Australian healthcare sector, such governance frameworks differ between federal and state health authorities and public and private healthcare organisations. Despite individual variations, what matters is that each is built upon sound guiding principles that serve to ensure an organisation’s data is secure and has integrity, quality, and usefulness.

The American Health Information Management Association’s ‘Information Governance Principles for Healthcare’ (IGPHC) were written to guide organisations that interact with and manage healthcare information, both clinical and non-clinical, and in electronic and hardcopy formats (Empel, 2014). The principles cover eight areas for information governance, including accountability; the integrity of information; compliance with relevant laws, policies and standards; retention; protection from breach, corruption, and loss; and secure processes to dispose of information that is no longer to be maintained according to law and/or organisational policies (Empel, 2014)

As we move to an increasingly interconnected digital environment, the use and protection of health data and information takes on new complexities and dimensions. Electronic data requires not only a bottom-up approach to information management, but also a top-down approach through information governance. Three important elements that tie into information governance are the ethical use of health data, cybersecurity, and privacy considerations in digital health.

Activity

Watch this short video on the WHO health data atlas. Consider the global use of data.

Digital Health Atlas: An Overview. Created by Digital Health Atlas by WHO Source : https://youtu.be/qEFzi0OtJMQ?si=b6mY3EWVYIYCxX3d

Ethics

There are many ethical challenges with the introduction of digital health technologies into the health and social care sectors and the caring professions are oriented by strong ethical principles relating to respect for human life and dignity, autonomy, care and justice.

While these principles serve to guide practice and behaviour relating to health data and information, the design and widespread use of digital technologies is beginning to broaden the complexity of ethical dilemmas encountered in healthcare.

A review of contemporary literature focusing on the ethics of digital health tools was reported by Caiani (2020), who identified issues such as the impact of social media/networking and health information sites on doctor-patient relationships, integration, and use of applications for self-management, data collection, sharing of images, the validity of information sources, health inequalities and accessibility. Health and social care leaders should include organisational policies and procedures and outline expected behaviours in codes of conduct to ensure the appropriate use of social media, sharing of health information and images.

As digital technologies continue to evolve further, more issues of moral concern will invariably be added to this list of ethical challenges in the digital health space.

Cybersecurity

The recent hacking in October 2022 of the Australian private health insurer Medibank Private by Russian cybercriminals highlights the vulnerability of any organisation, regardless of size, to have sensitive health data stolen and exposed in the public domain.

A Health Snapshot report from the Australian Cyber Security Centre, (2020) promoted an awareness of key threats and encouraged enhancements to cybersecurity across the sector. It revealed that other than the government or individuals, the health sector reported the highest number of incidents (Australian Cyber Security Centre, 2020). Cybersecurity is an increasingly significant challenge for the health and social care sectors.

Health and social care organisations can prepare themselves by addressing eight essential mitigation strategies, known as the ‘Essential Eight’ (Australian Cyber Security Centre, 2022). Whilst there is no guaranteed approach, the ‘Essential Eight’ are regarded as a baseline (Australian Cyber Security Centre, 2022). It is important to understand that health workers and professionals all play a role in the protection of digital health information.

The baseline eight approaches to mitigate against cybersecurity risks are shown in the table below.

The Essential 8 – Baseline Strategies to Mitigate Against Cyber Threats. Adapted From Australian Cyber Security Centre (2022)

| # | Mitigation approach | Explanation |

| 1 | Application control | Regularly checking programs installed against a pre-defined approved list and blocking all programs not on this list. |

| 2 | Patch applications | Ensuring that all patches to software are applied and up to date. Not permitting the use of applications that are out-of-support or do not receive security fixes. |

| 3 | Configure Microsoft Office macro settings | Only allowing Office macros (automated commands) where there is a business requirement and restrict the type of commands a macro can execute and monitoring the usage of macros. |

| 4 | User application hardening

|

Configuring key programs (office, web browsers, PDF software, etc) to apply settings to make it more difficult for an attacker to run commands that will install malware on systems. |

| 5 | Restrict administrative privileges | Administrator privileges are the ‘keys’ and limit the way that accounts with privileges administer and alter security and system settings can be used and accessed. |

| 6 | Patch operating systems | Ensuring that all patches to operating systems are timely and up to date (48 hours). Remove operating system versions that are no longer supported, superseded or out of date. |

| 7 | Implement multi-factor authentication | Using methods to validate user logins by applying additional checks, separate to password such as fingerprint scans or codes from SMS/mobile application. |

| 8 | Regular backups | Ensuring that regular backups occur should an attack occur to support rollback and restoration. Testing the restoration process when a backup is implemented, annually, and when software or IT infrastructure is changed. |

Privacy

Information privacy is one of the most significant consumer and citizen protection issues in the digital age. Information privacy is concerned with how an individual’s personal information is handled and the ways of promoting the protection of information (Office of the Australian Information Officer, n.d.)

Each country will be bound by their own privacy legislation; however, in Australia, the Privacy Act of 1988 introduced a set of Australian Privacy Principles (APPs). These principles apply widely and provide a framework for privacy protection, noting that organisations can adapt their data and information management practices to suit their practices.

There are 13 APPs relating to standards, obligations, and rights for:

- the collection, use and disclosure of personal information,

- an organisation or agency’s governance and accountability,

- the integrity and correction of personal information, and

- the rights of individuals to access their personal information (Office of the Australian Information Officer, n.d.).

The Office of the Australian Information Commissioner (n.d.) is the key federal government agency charged with providing resources, advice, and guidance about privacy principles and privacy management practices.

However, health and social care data and information is particularly sensitive; may be collected, stored, and disclosed by multiple entities in multiple locations; and has a long ‘shelf-life’. For these reasons, higher standards for privacy and confidentiality of health data are required, meaning that the maintenance of privacy is more complex in health than in other sectors (Hovenga and Lloyd, 2006).

This federal privacy legislation in Australia covers generic privacy principles, and jurisdictions such as NSW, Victoria and the ACT have enacted legislation explicitly related to health data.

Data Use and Analytics

Digital transformation creates a rich data foundation for health and social care services and new information and data can provide insights and support decision-making in new ways.

Leaders and managers of health and social care services are faced with making decisions related to resourcing, workforce, asset management, risk, and quality and safety. Leaders set the direction for their organisation to deliver on mission, vision, strategy, and goals. They draw on their experiences and, where possible, operational information and reports to reflect on performance, and make decisions about where to direct resources and if priorities require adjustment on this basis. Operational data collected in health information systems have informed healthcare leaders’ decision-making. As the use of digital health solutions increases, there is an increased capacity to capture, use, and analyse volumes of data.

Advances in digital health have redefined the value of information and the capacity of healthcare services to operate as intelligent organisations and draw on information in real-time, and be agile and more responsive.

One of the strengths of digital innovation is the capacity for data analytics and visualisation techniques. These can provide new insights, intelligence, and increased organisational resilience (Gopal et al., 2019). A systematic review of the value of big data analytics in healthcare found that the capabilities that can be developed from the use of big data analytics include:

- Better diagnosis for personalised care that allows services and therapeutic approaches to be tailored to individuals.

- Supporting professionals’ decision making with algorithms that can categorise symptoms and clinical results and provide recommendations for possible diagnoses and treatment through analytics.

- New models of care and different ways for consumers to interact with healthcare.

- Enabling experimentation that can test “what-if” scenarios, expose variability, and improve performance.

- Healthcare information sharing and coordination.

- Create data transparency.

- Identify and predict risks.

- Reduce expenditure while maintaining quality.

- Protecting privacy when data is extracted by eliminating ID recognition from electronic medical records (Galetsi, Katsaliaki, and Kumar, 2020).

Implementation

Leaders can support the implementation of digital technologies by providing an environment where innovative ideas can be trialled, tested, refined, and spread at scale. Greenhalgh et al. (2017, p1) conveyed that “many promising technological innovations in health and social care are characterised by non-adoption or abandonment by individuals or by failed attempts to scale up locally, spread distantly, or sustain the innovation long term at the organisation or system level”. Given a case for the introduction of the technology, a focus on change management, choice of implementation approach, project management, and an understanding of organisational readiness for adoption of digital solutions are all factors of successful uptake. Understanding the impact of politics and power are essential when implementing digital health technologies.

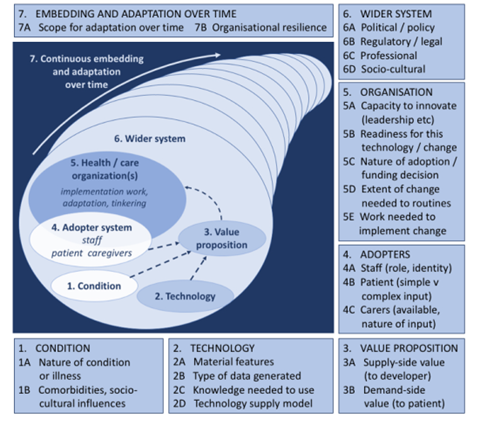

The NASS framework is an evidence-based tool developed by Greenhalgh et al. (2017, p.1) that has “several potential uses: (1) to inform the design of a new technology; (2) to identify technological solutions that (perhaps despite policy or industry enthusiasm) have a limited chance of achieving large-scale, sustained adoption; (3) to plan the implementation, scale-up, or rollout of a technology program; and (4) to explain and learn from program failures”. The figure below shows the framework that provides a set of domains and questions that should be considered in the non-adoption, abandonment, scale-up, spread, and sustainability (NASSS) framework for health and care technology (Greenhalgh et al., 2017). The framework recognises the complexity of the health environment and that reducing complexity in as many domains is necessary to maximise the success of technology projects, (Greenhalgh and Abimbola, 2019). To manage complexity, Greenhalgh and Abimbola (2019) suggested that the following approaches be applied

- Strengthen leadership of the initiative. Leaders can support adopters and model the vision.

- Have a clear and compelling vision for the initiative that is co-developed with stakeholders.

- Understand and talk about uncertainty, especially when it cannot be resolved.

- Recognise that change is hard and develop individuals to manage change and support the actions they take when implementing the technology.

- Work with front-line staff to refine the details (needed to adopt the innovation) and to achieve broad organisational objectives.

- Provide some slack in resourcing and dedicated time to lead and manage change and complete the tasks required in the implementation.

- Build relationships/partnerships to manage and resolve conflict. Relationship management with vendors for IT/IS solutions is critical

- Co-design work routines with intended end-users of the innovation. Involve them early and through the adoption. Small tests and pilots can be successful.

- Respond to emerging issues. Innovation will most always result in some unintended consequences and be alert and adaptive when these arise.

- Understand and work with credentialling, policy and/or regulatory requirements.

Workforce

Digital health implementation often proceeds without the specialised workforce development required to deliver successful outcomes and benefits (Gray et al., 2019). The workforce for a digitally enabled healthcare system remains a challenge and impacts digital health adoption and implementation.

Healthcare is information intensive, and as healthcare strives to maintain high levels of service to cope with demand and curb increasing costs, digital transformation requires preparation and planning for the change impacts on the workforce, workflow and resources. In the United Kingdom, a report explored how the healthcare workforce should be prepared to deliver the digital future and noted that “There is little point in investing in the latest technology if there is not a workforce with the right roles and skills to make use of its full potential to benefit patients” (Topol, 2019).

Internationally, the digital health workforce is not well understood or described, and the roles and competencies required to work successfully in digital health vary depending on the application. Research conducted in Australia identified no readily recognisable, specialised, professional health workforce available to govern and manage digital health (Gray et al., 2019). The World Bank (2023, p. 82) states that “no curricula on digital health exist at preservice or in-service levels. There is low maturity across most countries. Greater investment and standardization are needed in preservice and in-service training for health professionals, the professionalization of digital health and career paths within the public sector, and gender representation within the digital health workforce and governance”.

A scoping review of frameworks for digital health competencies identified the frameworks available to inform the development of digital health curricula, education, and training initiatives (Nazeha et al., 2020). Key frameworks identified were Health Information Technology Competencies (HITCOMP), which provides a tool and repository to compile information on skills and competencies needed for a variety of healthcare roles, levels, and areas of knowledge. HITcomp uses five domains and documents more than 1000 competencies. The five domains are: direct patient care, administration, informatics, engineering/IS/ICT, and research/biomedicine. The competencies are also aligned to a particular level of skill (baseline, basic, intermediate, advanced, and expert). Competencies are also mapped to over 250 health IT-impacted roles in acute care and other healthcare settings in each of the five domains (HITComp, 2020).

The Technology Informatics Guiding Education Reform (TIGER) coalition produced a set of competencies for those providing direct patient care, including communication, documentation, quality and safety management, teaching, training/education, and ethics in health information technology (Hübner et al., 2019).

A digitally capable health workforce will have the following skills:

- Confidence in the use of technologies and systems to capture data, present, interpret and share information.

- Ability to apply data science techniques to enable evidence-based decision-making and informed planning.

- Knowledge of information governance and security.

- Ability to work with vendors and specify requirements for systems that can support workflow management and support the interdisciplinary team and consumers of healthcare.

- Business skills to create the case for technologies and identification of benefits (Australian Digital Health Agency, 2020; Australian Institute of Digital Health, 2022).

The below table shows a diverse range of professions and associated digital competencies.

Example digital competencies by profession

| Profession | Digital competencies |

| Health service managers and leaders | Manages business and clinical requirements using digital tools.

Advocates for the use of digital health solutions to support innovation, quality improvement, research, and health service management. Aligns corporate, clinical, and information governance. Ensures digital health solutions meet functional and user requirements. Uses digital health solutions safely, minimising unintended consequences. Uses advanced analytics methods and visualisation techniques for information representation. Promotes digital health literacy. (Australasian College of Health Service Management, 2022) |

| Health information managers | Domains of:

(Health Information Management Association of Australia, 2017)

|

| Health informaticians – Australia | The CHIA exam covers six areas:

(Australian Institute of Digital Health, 2022)

|

| National Nursing and Midwifery Digital Health Capability Framework | Domains addressing

(Australian Digital Health Agency, 2020)

|

| Allied health professionals | Domains addressing:

(Victoria. Department of Health, 2021) |

| Primary care professionals | Optimal use of EMRs, basic computer and internet use, knowledge about digital administrative and organisational competencies, artificial intelligence, and smartphone applications for monitoring care (Jimenez et al., 2020)

|

| Digital Capability Framework for Health and Social Care for Ireland and Northern Ireland

|

Domains addressing

(Health Service Executive and Digital Health and Social Care Northern Ireland, 2022) |

| Competency framework for clinical informatics in the United Kingdom | Domain 1 Health and wellbeing in practice

Domain 2 Information technology and systems Domain 3 Working with data and analytical methods Domain 4 Enabling human and organisational change Domain 5 Decision making Domain 6 Leading informatics teams and projects (Davies et al., 2021)

|

Options for Building a Digital Health Workforce

A workforce to support digital transformation requires planning to ensure that the right skills are available in the right place at the right time. In the 21st century, all health professionals need to be able to use digital technologies in their roles. However, a variety of specialised skills are required to support digital transformation, including clinicians, systems analysts, engineers, programmers, web-application developers, enterprise architects, integration specialists, data scientists, health informaticians, health information managers, health economists, and cyber analysts. This list is not exhaustive, and training and education are required to develop the required workforce.

Within healthcare organisations, a plan that includes the digital health workforce and that identifies how the workforce can be attracted, retained, and developed is an essential component of organisational strategy and planning. (See the chapter on Talent Management, Recruitment and Selection). Elements of a digital workforce plan might include a range of elements, including those outlined in the table below.

Elements for a Digital Workforce Plan

| Approach | Explanation |

|

Recruitment, retention, and talent management

|

Ensuring that the health care organisation attracts, retains, and develops the skills required to implement, continually improve, and align digital health technologies with organisational mission, vision, and strategies.

|

| Retrain and upskill

|

One approach can be to support the workforce to retrain and learn through education and training provided by registered training organisations or vocational education and university sectors. Programs can be tailored to the needs of the organisation or specific skills or deficits.

|

A digitally enabled healthcare system also requires that users and receivers of care are equipped with both the technology and skills to successfully participate in managing their health and receiving treatment. Implementing digital health solutions may have unintended consequences for health equity, as lack of access to devices, poverty, and digital health literacy are some factors that contribute to poor health outcomes (Crawford and Serhal, 2020; Kaihlanen et al., 2022).

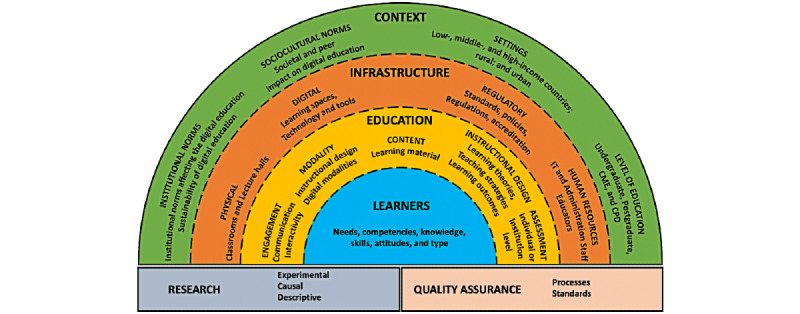

To address the challenge of health professional digital education, Car et al. (2022) developed an evidence-based conceptual framework. The framework defines the need for a supportive and enabling context, sound infrastructure, and the optimal use of educational tools and processes. Learners have their own needs, preferences, prior experience, and competencies, and this should shape how education is delivered. For example, EMR training that demonstrates to clinicians user shortcuts, optimal use of the system, and approaches that shift from the traditional classroom teaching to techniques such as interactive and workflow-based content and hands-on rehearsals in simulated work environments can be effective (Scott et al., 2018; Ting, Garnett, and Donelle, 2021). The figure below shows a framework and the elements that should be considered when educating health professionals for digital technologies and information systems.

Conclusion

Digital health offers prospects to achieve sustainable, high-quality, safe health outcomes for all. Globally, many nations are experiencing challenges with workforce shortages, aging populations, and an explosion in chronic diseases. As health leaders, we need to think for the ‘information age’, as described in this chapter, and link digital health solutions to strategy to solve real problems. There have been examples of large-scale investment in digital health solutions; for example, the electronic medical record to replace paper-based record keeping; however, workflows and service design have remained largely unchanged.

For the future, it is imperative that we think differently when implementing digital technologies in complex health and social care settings. We need to avoid ‘bolting’ technology onto the edges of traditional, place-based care delivery, and make a paradigm shift from what Greenhalgh et al., (2010) described as paternalistic, disease-focused models of care in health and social care to one of the self-managing consumers, with their health at the centre. While there will always be a place for tertiary-level care by hospitals and other services, the benefits to be realised from the digital era are to rethink how and where care is delivered. Health and social care leaders who set a compelling vision and direction for digital health, that build the foundations and plan for digital health, and who apply digital health solutions to solve the problems and challenges faced will seize the opportunities that digital health promises.

Key Implications for Practice

Leaders in health and social care can assure the best use of digital health by focusing on the following:

- Foundations – ensuring that the foundations to build a digital health system are in place.

- Vision, leadership, and culture – aligning digital health acquisitions to achieving strategic goals and objectives to improve care and the delivery of health and social care services. Planning for and investing in digital solutions that can solve a real or identified challenge to the delivery of high quality and safe care.

- Governance and ethics – adopting strong information governance frameworks, policy and procedures and ensuring information is managed securely.

- Implementation – Providing resources to implement digital health projects well; understanding the context, political situation, and stakeholders; evaluating technology projects; and learning and improving.

- Workforce – planning for and ensuring that the workforce is prepared and trained to use technologies to help them to complete their work safely.

The success factors are summarised in the table below.

Success factors in digital health

|

Foundations

|

Vision, Leadership, and Culture

|

Governance and Ethics

|

Workforce

|

Implementation

|

|

High speed internet and communications

Hardware Software Applications Storage Standards |

Clear vision for role of digital transformation.

Alignment of digital strategy with organisational goals and priorities. Investment in digital solutions and infrastructure. Culture supports new ideas and learns from mistakes. |

Strong information governance.

Policy and procedures. Management of the digital assets. Information security. |

Right mix and number of skilled and digitally capable people.

Workforce plans that include the digital workforce. |

Resources

Change management Project management Evaluation and learning |

Key Takeaways

For leaders, you will know you are successful if….

- Your organisation has a clear vision as to how digital technologies will support the organisation to achieve its mission and deliver on strategy.

- Leaders at all levels are promoting the vision for and the integration of digital technologies to solve workplace challenges and support individuals with innovative ideas to implement them.

- Employees within the organisation are comfortable suggesting and trialling new ideas and learn from any mistakes.

References

Australasian College of Health Service Management. 2022. Master Health Service Management Competency Framework. Sydney, Australia. Available at: https://www.achsm.org.au/education/competency-framework

Australian Cyber Security Centre. 2020. 2020 Health Sector Snapshot. Available at: https://www.cyber.gov.au/acsc/view-all-content/reports-and-statistics/2020-health-sector-snapshot

Australian Cyber Security Centre. 2022. Essential Eight Maturity Model. Available at: https://www.cyber.gov.au/resources-business-and-government/essential-cyber-security/essential-eight/essential-eight-maturity-model

Australian Digital Health Agency. 2020. National Nursing and Midwifery Digital Health Capability Framework. Available at: https://www.digitalhealth.gov.au/sites/default/files/2020-11/National_Nursing_and_Midwifery_Digital_Health_Capability_Framework_publication.pdf accessed 2 December 2022

Australian Digital Health Agency. 2018. Safe, seamless and secure: evolving health and care to meet the needs of modern Australia: Australia’s National Digital Health Strategy. Available at: https://www.digitalhealth.gov.au/about-us/strategies-and-plans/national-digital-health-strategy-and-framework-for-action

Australian Institute of Digital Health. 2022. Australian Health Informatics Competency Framework. https://digitalhealth.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/AHICFCompetencyFramework.pdf

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. 2021. Chronic condition multimorbidity. Available at: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/chronic-disease/chronic-condition-multimorbidity/contents/chronic-conditions-and-multimorbidity

Baghizadeh, Z., Cecez-Kecmanovic, D. and Schlagwein, D. 2020. Review and critique of the information systems development project failure literature: An argument for exploring information systems development project distress. Journal of Information Technology, 35(2), pp.123-142.

Bansal, G., Rajgopal, K., Chamola, V., Xiong, Z. and Niyato, D. 2022. Healthcare in metaverse: A survey on current metaverse applications in healthcare. Ieee Access, 10, pp.119914-119946.

Caiani, E. 2020. Ethics of digital health tools. European Society of Cardiology 1827.

Coleman, K., Wagner, E., Schaefer, J., Reid, R. and LeRoy, L. (2016). Redefining primary care for the 21st century. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 16(20), 1-20.

Crawford, A. and Serhal, E. 2020. Digital health equity and COVID-19: The innovation curve cannot reinforce the social gradient of health. Journal of Medical Internet Research. JMIR Publications Inc. DOI: 10.2196/19361.

Davies, A., Mueller, J., Hassey, A. and Moulton, G. 2021. Development of a core competency framework for clinical informatics. BMJ health & care informatics, 28(1).

Empel, S. 2014. Way Forward: AHIMA Develops Information Governance Principles to Lead Healthcare Toward Better Data Management. Available at: www.ahima.org/topics/infogovernance.

Galetsi, P., Katsaliaki, K. and Kumar, S. 2020. Big data analytics in health sector: Theoretical framework, techniques and prospects. International Journal of Information Management, 50, pp.206-216.

Gauld, R. 2007. Public sector information system project failures: Lessons from a New Zealand hospital organization. Government Information Quarterly 241: 102–114. DOI: 10.1016/j.giq.2006.02.010.

Gopal, G., Suter-Crazzolara, C., Toldo, L. and Eberhardt, W. 2019. Digital transformation in healthcare–architectures of present and future information technologies. Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine (CCLM), 57(3), pp.328-335.

Gray, K., Gilbert, C., Butler-Henderson, K., Day, K. and Pritchard, S. 2019. Ghosts in the Machine: Identifying the Digital Health. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/335502203_Ghosts_in_the_Machine_Identifying_the_Digital_Health_Information_Workforce

Greenhalgh, T. and Abimbola, S. 2019. The NASSS Framework A Synthesis of Multiple Theories of Technology Implementation. Studies in Health Technology and Informatics 263. IOS Press: 193–204. DOI: 10.3233/SHTI190123.

Greenhalgh, T., Hinder, S., Stramer, K., Bratan, T. and Russell, J. 2010. Adoption, non-adoption and abandonment of an Internet-accessible personal health organiser: Case study of HealthSpace. BMJ, 201, p.c5814.

Greenhalgh, T., Wherton, J., Papoutsi, C., Lynch, J., Hughes, G., Hinder, S., Fahy, N., Procter, R. and Shaw, S. 2017. Beyond adoption: a new framework for theorizing and evaluating nonadoption, abandonment, and challenges to the scale-up, spread, and sustainability of health and care technologies. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 19(11), p.e8775.

Gupta., M. 2018. Blockchain for Dummies. 2nd ed. New Jersey: John Wiley and Sons Inc.

Health Information Management Association of Australia. 2017. Health Information Manager HIM Competency Standards v 3. Available at: https://himaa.org.au/competency-standards/

Healthcare Information and Management Systems Society. 2022. Interoperability. Available at: https://www.himss.org/resources/interoperability-healthcare

Health Service Executive and Digital Health and Social Care Northern Ireland. 2022. Digital Capability Framework for Health and Social Care. https://online.hscni.net/digital-hcni/digital-capacity-capability/

HITComp. 2020. Health Informatics Competencies. Available at: http://hitcomp.org/competencies/

Hovenga, E. and Lloyd, S. 2006. Working with Information – Chapter 10. In: Harris and Associates ed. Managing Health Services Concepts and Practices. 2nd ed. Elsevier.

Hübner, U., Thyea, J., Shaw, T., Elias, B., Egbert, N., Saranto, K., Babitsch, B., Procter, P. and Ball, M., 2019. Towards the tiger international framework for recommendations of core competencies in health informatics 2.0: extending the scope and the roles (pp. 1218-1222). IOS Press.

IBM. n.d. What is blockchain technology? Available at: https://www.ibm.com/au-en/topics/what-is-blockchain

Isakovic, M., Cijan, J., Sedlar, U., Volk, M. and Bester, J. 2015. The Role of mHealth applications in societal and social challenges of the future. In 2015 12th International Conference on Information Technology-New Generations (pp. 561-566). IEEE.

Jimenez, G., Spinazze, P., Matchar, D., Huat, G. K. C., van der Kleij, R. M., Chavannes, N. H. and Car, J. 2020. Digital health competencies for primary healthcare professionals: a scoping review. International Journal of Medical informatics, 143, p.104260.

Kaihlanen, A. M., Virtanen, L., Buchert, U., Safarov, N., Valkonen, P., Hietapakka, L., Hörhammer, I., Kujala, S., Kouvonen, A. and Heponiemi, T. 2022. Towards digital health equity-a qualitative study of the challenges experienced by vulnerable groups in using digital health services in the COVID-19 era. BMC Health Services Research, 22(1), p.188.

Kaplan, B. and Harris-Salamone, K. D. 2009. Health IT Success and Failure: Recommendations from Literature and an AMIA Workshop. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association 163: 291–299. DOI: 10.1197/jamia.M2997.

Kolitsi, Z., Kalra, D., Wilson, P., Martins, H., Stroetmann, V., Schulz, C., Birov, S., Fabricius, C., Empirica Team and DHE Partners. 2021. Digital Transformation of Health and Care in the Digital Single Market and its initiative for a European Health Data Space. Available at: https://digitalhealtheurope.eu/

Lawry, T. 2020. AI in Health : A Leader’s Guide to Winning in the New Age of Intelligent Health Systems. Healthcare Information & Management Systems Society.

Medical Futurist. 2021. What is digital health: definition. Available at: https://medicalfuturist.com/wiki/digital-health/

Nazeha, N., Pavagadhi, D., Kyaw, B.M., Car, J., Jimenez, G. and Tudor Car, L. 2020. A digitally competent health workforce: scoping review of educational frameworks. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 22(11), p.e22706.

New Zealand Ministry of Health. 2022. Digital health. Available at: https://www.health.govt.nz/our-work/digital-health

NSW Government – Finance, Services and Innovation. 2019. Internet of Things IoT Policy Statement. https://arp.nsw.gov.au/dcs-2019-01-internet-things-policy/

Office of the Australian Information Officer. n.d. Australian Privacy Principles. Available at: https://www.oaic.gov.au/privacy/australian-privacy-principles

Olano, C. 2019. Swallowable capsules are not only for videos. Endoscopy International Open 0706. Georg Thieme Verlag KG: E782–E783. DOI: 10.1055/a-0884-2992.

Russell, S. and Norvig, P. 2022. Artificial Intelligence: A Modern Approach. Eds S Russell and P Norvig. 4th ed. Pearson Education.

Scott, I.A., Sullivan, C. and Staib, A. 2018. Going digital: a checklist in preparing for hospital-wide electronic medical record implementation and digital transformation. Australian Health Review, 43(3), pp.302-313.

Stevens, G., Hantson, L., Larmuseau, M. and Verdonck, P. 2022. A human-centered, health data-driven ecosystem. Discover Health Systems, 1(1), p.10.

Thomason, J. 2021. MetaHealth – How will the Metaverse Change Health Care? Journal of Metaverse 11: 13–16. Available at: https://dergipark.org.tr/en/download/article-file/2167692

Hübner, U., Thyea, J., Shaw, T., Elias, B., Egbert, N., Saranto, K., Babitsch, B., Procter, P. and Ball, M., 2019. Towards the tiger international framework for recommendations of core competencies in health informatics 2.0: extending the scope and the roles (pp. 1218-1222). IOS Press.

Ting, J., Garnett, A. and Donelle, L. 2021 Nursing education and training on electronic health record systems: An integrative review. Nurse Education in Practice 55July. Elsevier Ltd: 103168. DOI: 10.1016/j.nepr.2021.103168.

Topol, E. 2019. Preparing the healthcare workforce to deliver the digital future. The Topol Review – An independent report on behalf of the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. https://topol.hee.nhs.uk/the-topol-review/

Tudor Car, L., Poon, S., Kyaw, B. M., Cook, D.A., Ward, V., Atun, R., Majeed, A., Johnston, J., Van der Kleij, R. M., Molokhia, M. and V Wangenheim, F. 2022. Digital education for health professionals: An evidence map, conceptual framework, and research agenda. Journal of medical Internet research, 24(3), p.e31977.

U.S. Food and Drug Administration. 2020 Digital Health Center of Excellence. Available at: https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/digital-health-center-excellence/what-digital-health

Victoria Department of Health. 2021. Digital health capability framework for allied health professionals. https://www.health.vic.gov.au/sites/default/files/2021-12/digital-health-capability-framework-for-allied-health-professionals.pdf

Woods, L., Eden, R., Canfell, O. J., Nguyen, K. H., Comans, T. and Sullivan, C. 2023. Show me the money: how do we justify spending health care dollars on digital health?. The Medical Journal of Australia, 218(2), p.53.

World Bank. 2023. Digital-in-Health: Unlocking the Value for Everyone. Available at: https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/health/publication/digital-in-health-unlocking-the-value-for-everyone

World Health Organization. 2020. Digital Implementation Investment Guide DIIG: Integrating Digital Interventions into Health Programmes. Available at: Digital Implementation Investment Guide DIIG: Integrating Digital Interventions into Health Programmes

World Health Organization. 2021. Global strategy on digital health 2020-2025. Available at: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/344249