Leadership

Cultural Safety and Awareness Frameworks in Health and Social Care: Whose Cultural Safety?

Jennifer Evans

Introduction

This chapter is about cultural safety and awareness frameworks and approaches for First Peoples in health and social care contexts. Various theories and models will be discussed, along with their implications for practice. The key messages from this chapter are that competency in cultural safety and awareness requires a continuous process of education, leadership, and accountability, at both organisational and interpersonal levels. All people have unconscious bias positioning (settler and other), and behaviours that flow from these in the context of healthcare, and the power imbalance that exists. Therefore, it is particularly important that health practitioners, workers, and administrators are open to and recognise their own settler and other positioning, unconscious bias, and racist behaviours in order to demonstrate sustainable and meaningful cultural safety for their First Peoples patients, health service consumers and colleagues. This also extends to First Peoples practitioners, who likewise require cultural safety and can be negatively impacted by unconscious bias and racist behaviours. I write this chapter from my own Indigenous standpoint as a Dharug person belonging to the First Peoples in Australia.

This chapter refers to First Peoples [1] in settler state [2]I use the term ‘settler states’ to refer to First People’s sovereign states which are colonised by invading settlers, whose occupation affords them political control over First Peoples.[/footnote] contexts in the Global North (e.g., Australia, New Zealand, Canada, and the United States of America). In settler states there are differing degrees of recognition and respect for First Peoples (Langton and Palmer, 2004; McDonald, 2023). Social justice and civil rights movements have given rise to the acknowledgement that settler mentalities are variable regarding how First Peoples are treated as human beings in all aspects of their lives (Fredericks et al., 2013; Collins and Watson, 2023). Workplaces, corporations, institutions, and communities have embarked on broad policies to improve the treatment of First Peoples under the banner of cultural respect, safety, awareness, and competency (Fleming, Creedy and West, 2018; Tremblay et al., 2023). Since the 1990s, some efforts have been made by the health and social care sectors to deliver appropriate cultural safety, awareness, respect, and competency education (Curtis et al., 2019). However, as of 2023, the impacts are variable; for example, in acute care settings racism, unconscious bias, and lack of cultural safety and respect towards First Peoples is resulting is improper and inequitable medical treatment and care (Abraham, Tauranga and Moore, 2018; Rahman et al., 2023). In Australia, there is “decades of evidence showing that institutional and interpersonal racism serve as significant barriers to accessible healthcare for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples” (Gatwiri, Rotumah and Rix, 2021, p. 1). Thus, there is still much work to be done by health practitioners, workers, administrators, and their organisations to deliver equitable and safe care for First Peoples.

Background

Why is cultural safety important?

There is an expectation that health practitioners, administrators, managers, leaders and general associated health workforce workers demonstrate cultural safety, respect, and competency at all points of First Peoples patient and consumer interaction in order to provide equitable access to health and social care (Greenwood et al., 2017; Mitchell et al., 2022). Hence, it is vital that appropriate policy settings and mechanisms are in place for cultural safety training underpinned by evaluation of performance, which need to be embedded and role modelled at all levels of health and social care services. In the absence of such integrated cultural safety approaches, First Peoples can be negatively impacted in varying ways (Browne et al., 2011; Chapman, Smith and Martin, 2014). For example, poor health outcomes (Milligan et al., 2021), lack of access to services (McLachlan et al., 2022), and perpetuation of racism and ongoing colonisation (Owens, Holroyd and McLane, 2020). All of these can contribute to continuing failures of state-based policies for equity of care of First Peoples, such as Closing the Gap [3](Altman, 2018), and may contravene international conventions such as the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (Browne et al., 2020).

It is important to note that tension exists between settler state responsibility and the individual health worker’s [4] responsibility to deliver culturally safe health and social care services (Downing, Kowal and Paradies, 2011). That is, both collective and individual responsibilities require leadership. Both spheres of responsibilities are vital for enduring change to deliver culturally safe, appropriate, and respectful health and social care services (Downing and Kowal, 2011; Gladman, Ryder and Walters, 2015). It is difficult to deliver this if both spheres of agency are not working together, as ongoing cooperation and commitment is required (Downing and Kowal, 2011; Mitchell et al., 2022). This chapter calls for leadership at all levels to improve outcomes for First People’s health.

What will you learn about cultural safety and why does it matter?

There are over 476 million Indigenous Peoples globally (United Nations, 2023), living on, caring for, and defending their rights, homelands, and ways of being across Earth (United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs [UN DESA], 2021). First Peoples are diverse and have specific ways of being and knowing. They are impacted by colonisation in varying ways (Pardadies, 2016; UN DESA, 2021). In some instances, First Peoples migrate or are displaced to places that are not their ancestral homelands, making their requirements for cultural safety distinct from the First Peoples homelands they are resettled in. Further, First Peoples are discrete within traditional estates and Nation areas and have well-defined tribal boundaries within nations, languages, and customs. Often, First Peoples are being serviced by settler health networks that do not reflect First Peoples geographies, but rather the geographies of colonisers [5]. Thus, the health and social care service and worker must understand that providing services that are culturally respectful requires recognition that “one size does not fit all” . Rather, that the practice of delivery of culturally safe and appropriate care requires specific knowledge, training, political action, and acknowledgement of diversity.

In this chapter, you will learn why cultural safety was established as a concept, and the different models, practices, and terminologies that developed over time. You will also learn about models and approaches to reaching cultural safety, the criticisms and debates surrounding them, and their limits for effective implementation. This chapter discusses how cultural safety models can be improved by applying Indigenous and decolonising methodologies and theories. A reflection on who ultimately benefits from cultural safety models and approaches is included. The chapter finishes with information about how to be a leader in the landscape of cultural safety frameworks.

Theory and models

Development of cultural safety concepts

The concept of cultural safety was initially championed by the work of Māori nurses in response to Western based nursing practices that ignored issues of power imbalances between health service providers and health care consumers (Ramsden, 2002). As a Māori nurse and scholar, Ramsden (2002) argued that “the nurse is exotic to the patient, and that only the person experiencing the service can say whether it is fully effective” and that cultural safety “gives power to the patient or families to define the quality of the service on subjective as well as clinical levels” (Ramsden, 2002, p. 110).

Williams (1999, p. 213) defined cultural safety as a means to evaluate and “determine pathways to genuine empowerment” for Indigenous clients and stakeholders using the following accepted definition developed by Eckerman et al. (1992, np.):

An environment which is safe for people; where there is no assault, challenge or denial of their identity, of who they are and what they need. It is about shared respect, shared meaning, shared knowledge and experience, of learning together with dignity, and truly listening.

In their paper, Williams (1999, p. 213) opened up the debate to encourage people to “examine their organisation, programs and their work practices” beyond ‘quick fixes’, economic imperatives and ‘conservative hegemonic practices’ around cultural safety. Emphasis for meaningful cultural safety was placed on no assault on a person’s identity (Williams, 1999).

Similarly, Fulcher (1998, p. 333) defined cultural safety within the context of Indigenous culture in the education and training of social workers working with children in New Zealand:

…state of being in which the [individual] knows emotionally that [their] personal wellbeing, as well as social and cultural frames of reference, are acknowledged – even if not fully understood. Furthermore, [they are] given active reason to feel hopeful that [their] needs and those of [their] family members and kin will be accorded dignity and respect.

Fulcher (1998, p. 335) concluded that “Indigenous peoples possess knowledge that we won’t allow ourselves to know because it doesn’t fit into our scientific paradigm”. Fulcher (1998) called for the acknowledgement of Indigenous culture in a day-to-day sense, coupled with the fundamental requirement for health practitioners to be open to learning more and thinking outside Western cultural frames of reference.

As the implementation of cultural safety programs and education began to develop, attention turned to the impact on cultural educators. Wepa (2003) studied the experiences of cultural safety educators in nursing education in Aotearoa, New Zealand to elucidate improvements required in cultural safety education. It was concluded that Māori educators were in a “state of perpetual stress”, lacked support and faced many issues out of their control (Wepa, 2003, p. 346). This led to further refinement of cultural safety as “unsafe cultural practice is any action that diminishes, demeans, or disempowers the cultural identity and well-being of an individual ” (Wepa, 2003, p. 340).

In 2010, the First Nations, Inuit and Mètis Advisory Committee, Mental Health Commission of Canada sought advice about cultural safety in application to Indigenous health. The authors advised that “cultural safety is not about ethnocultural practices, rather it highlights the need for the development of critical consciousness toward the power differentials inherent in the health care system as well as the broader socio-historical and political factors that shape health care and Indigenous health” (Smye, Josewski and Kendall, 2010, p. ii). The narrative around cultural safety had shifted focus toward “social, structural and power inequities… prompting moral and political discourse and dialogue” (Smye, Josewski and Kendall, 2010, p. ii).

Models and stages of reaching cultural safety

Since then, a body of work has focused on the models and stages that aim to achieve cultural safety, ranging from cultural awareness to cultural competence, cultural sensitivity, cultural respect, cultural capability, cultural responsiveness, cultural security, and cultural safety (Coffin, 2007; Phiri, Dietsch and Bonner, 2010; Heckenberg, 2020; Gollan and Stacey, 2021). However, cultural safety has been adopted as the preferred term as it was developed in an explicit First Peoples context, as opposed to cultural competence developed in a cross-cultural context (applicable to people from diverse cultural backgrounds) (Gollan and Stacey, 2021). Further, some argue that the term cultural competence is an unrealistic goal for non-Indigenous people due to the diversity among First Nations groups (Gollan and Stacey, 2021) and the Anglo-privilege, homogeneity, and lack of diverse lived experiences of some non-Indigenous peoples (Dunn et al., 2010; Durey and Thompson, 2012). Cultural diversity is mutually embedded in place and people (Kassam 2008). Thus, First Peoples in situ [6] are best placed to determine the “presence or absence of cultural safety” (Gollan and Stacey, 2021, p. 8) according to their culture.

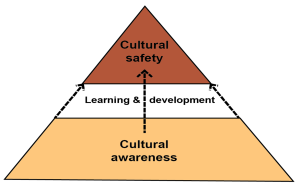

Models and stages of reaching cultural safety are illustrated in the figure below. It summarises the components and stages for reaching cultural safety according to the models developed by Heckenberg (2010), Phiri, Dietsch, and Bonner (2020), and Coffin (2007). These models agree that attainment of cultural safety practices must involve sequential learning and development starting at the foundation of cultural awareness. The applicability of cultural competence and cultural security differ in the models, as does cultural sensitivity. This reflects current debates about how cultural safety practices might be achieved.

Heckenberg (2020) proposed that cultural safety regarding Indigenous Peoples is the culmination of processes of individual and or institutional personal growth and education, such that the coloniser reaches an understanding and practice of cultural safety after developing cultural awareness, sensitivity, and competence. Whereas Phiri, Dietsch and Bonner (2010) excluded cultural competence, moving from the stage of cultural sensitivity to applied cultural safety. However, it is noted that Phiri, Dietsch and Bonner (2010) applied their model to culturally diverse groups (cross-cultural), not exclusively to First Peoples. This highlights the nuances present in the application of cultural safety models, whereby the unaware reader may miss the importance of understanding and applying cultural safety models from an Indigenous Standpoint (Nakata, 2007), including the specificities required for caring for First Peoples as a separate group (Gollan and Stacey, 2021).

Coffin (2007) moved beyond cultural safety to cultural security in their focus on Aboriginal People in Australia. “Cultural security directly links understandings and actions. Policies and procedures create processes that are automatically applied from the time when Aboriginal people first seek health care” (Coffin, 2007, p. 23). Coffin (2007) focussed on cultural security as the ultimate goal, requiring processes of cultural praxis and critical reflection, protocols and brokerage to move beyond measures of ‘competence’ to address power differentials.

Regarding cultural safety, Cox and Best (2022, p. 78) argued that “cultural safety clarifies the connection between interpersonal racism and institutionalised systems of privilege/discrimination”. This view is supported by Downing and Kowal, (2011, p. 12), who proposed that cultural safety frameworks are more beneficial as they “move beyond cultural training in action” to requiring the health worker to understand their own culture and identity, unequal power balances, and “processes that may be sites of colonial practice”. Therefore, cultural safety must be embedded in health profession course accreditation, standards governing clinical professionalism and quality, and measures must be taken to reduce resistance (Laverty, McDermott and Calma, 2017).

Some argue that there is no one model (cultural safety versus cultural competence) adequate enough to address health disparities and the diverse local histories and politics that shape them (Kirmayer, 2012). For Australia, New Zealand, Canada, and the USA “there is a lack of evidence from rigorous evaluations on the effectiveness of interventions for improving cultural competency in health care for Indigenous Peoples” (Clifford et al., 2015, p. 89). Jongen et al. (2018) argued that the fault of the failure of cultural competency lies in the fact that the health sector (where the power is held) has not fully acted on the philosophy and practice of cultural competency. Merlo (2021) went further to define structural competence, which relates to the requirements of physicians to address systematic problems and unconscious or implicit bias that cause healthcare inequities. Similarly, others have found that organisational and service-level strategies and policies are required to address structural barriers to achieving cultural respect for health care practitioners (Freeman et al., 2014). There is also criticism that cultural awareness frameworks (the foundation of the models in the above figure) have questionable efficacy, essentialise and other Indigenous culture and Peoples, and re-inscribe power differences between health services and First Peoples (Downing, Kowal and Paradies, 2011).

Criticisms of cultural safety models

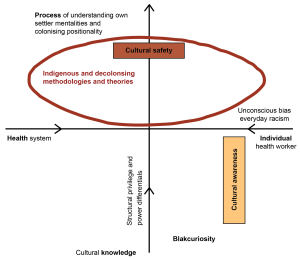

In their review of approaches to Indigenous cultural training for health workers in Australia, Downing, Kowal and Paradies (2011) found that evidence of their effectiveness was poor. They identified six major models by which cultural training can be conceived: “cultural awareness, cultural competence, transcultural care, cultural safety, cultural security, and cultural respect” (Downing, Kowal and Paradies, 2011, p. 248). The figure below (adapted from Downing, Kowal and Paradies, 2011) shows two of these models (cultural safety and cultural awareness) plotted on an x axis (individual versus systemic behavioural change) and y axis (individual understanding of their own culture and processes of identity versus understanding the culture of others). Downing, Kowal and Paradies (2011) were critical of cultural training programs, in particular, the cultural awareness model, arguing that it focuses on limited conceptualisations of culture and identity, while failing to examine the culture of health workers or the health system; thus, implicitly positioning them as the norm. This view is supported by Downing and Kowal (2011 p. 8) who argued that the cultural awareness framework (when analysed using postcolonial theory) creates “essentialism, ‘othering’, and allows ‘the negligence of systemic responsibility’ creating a ‘limited conceptualising of culture and identity may explain its failure to contribute to the development of culturally appropriate health services’”.

Whilst Downing, Kowal and Paradies (2011, p. 247) concluded that the cultural safety model “may offer the most potential to improve the effectiveness of health services for Indigenous Australians”, they warned that the current models continue to produce power imbalances, social inequality and ‘othering’. They further suggested that Indigenous cultural training can create a “false sense of cultural knowledge” and that emphasis should be placed toward understanding processes of formation and one’s own identity/positioning (Downing, Kowal and Paradies, 2011, p. 254).

Key implications for practice

Using Indigenous theories to improve cultural safety models

Given the limitations of cultural awareness frameworks and its implied complicity regarding health worker and systems negligence (Downing, Kowal and Paradies, 2011; Downing and Kowal, 2011), I question the cultural safety models previously mentioned (Coffin, 2007; Phiri, Dietsch and Bonner, 2010; Heckenberg, 2020), as these models are founded on cultural awareness as the first step in achieving cultural safety and appear to lack explicit Indigenous theoretical frameworks. Perhaps the conception of their models may benefit from a critical review using Indigenous and decolonising methodologies and theories?

One way that this could be achieved is to review the theoretical models for cultural safety presented by Downing, Kowal and Paradies (2011). In the Decolonising the theoretical models used in Indigenous cultural safety training figure above, I have inserted a red shield as the site for potential application of Indigenous and decolonising methodologies and theories in their comparison of theoretical models. My site is a location of resistance against settler possession of cultural awareness frameworks, a place to protect First Peoples from ongoing colonisation; thus, a shield is appropriate. My shield site aims to focus on the entire x axis to include both the health system and health worker, whilst seeking improvements for both toward the positive y axis to address power differentials between First Peoples and the health system and health worker. At my site, Whiteness theory (Moreton-Robinson, 2004, 2008, 2015) and Indigenous Standpoint theory (Nakata, 2007) are coupled with an Indigenous Research Agenda (Smith, 1999) as decolonising methodologies to seek insights for improvement of cultural safety models.

Whiteness theory is powerful when challenging the superiority of the settler in colonised states and expanding understandings of the complexities of Indigeneity (Moreton-Robinson 2004, 2009). Moreton-Robinson (2008, p. 85) stated that “it [Whiteness] is a location of structural privilege, a subject position and cultural praxis. Whiteness constitutes the norm operating within various institutions influencing decision making and defining itself by what it is and is not”. Whiteness theory can assist in understanding how power relations are informed by racialised knowledge, and how such knowledge can regulate subjugation (Moreton-Robinson, 2006). Whiteness theory is useful in addressing racialised practices that are deeply embedded in health systems and reproduce unsafe practices (Gatwiri, Rotumah and Rix, 2021).

At my shield site, Whiteness theory could assist the health worker by encouraging them to engage with notion that the acquiring of cultural knowledge (bottom of y axis) without recognition of their own settler mentalities may bring implicit bias, explicit racism, perpetuate colonisation, and entrench cultural unsafety, personally and within the health systems they operate. The strength of Whiteness theory is that it has the potential to shine light on power differentials and talk back and up to dominant white structures and systems (Moreton-Robinson, 2015). This would be beneficial for health workers to move from the position of potentially learning to “hug a blackie” (Hunter, 2001, as cited in Fredericks, 2006, p. 88), becoming faux-woke [7] or Blakcurious [8] (by limiting their training to cultural awareness) towards recognising their colonising positionality and impact on First Peoples (fully embracing cultural safety).

At the cultural interface where Indigenous and Western systems collide, Indigenous Standpoint theory helps us make sense of our everyday lives as First Peoples (Nakata 1997, 2007). Nakata (2007, p. 12) described their Indigenous Standpoint theory as a “method of enquiry, a process for making more intelligible ‘the corpus of objectified knowledge about us’”. The great strengths of Nakata’s Indigenous Standpoint are that it can “generate accounts of communities of Indigenous People in contested knowledge spaces” and aims to “acknowledge the everyday tensions as the very conditions to what is possible between Indigenous and non-Indigenous positions” (Nakata, 2007, p. 13). At my site, Indigenous Standpoint theory works in a similar way to Whiteness theory, in that it brings into sharp focus the objectification of First Peoples and their cultural knowledges as a consequence of the health worker focusing on developing cultural knowledge (cultural awareness) at the low end of the y axis. At this location, an Indigenous Standpoint speaks to the everyday tensions of being First Peoples and reflects the innate reality of everyday racism possible through abdication of the health worker and the health system in addressing their settler privilege and power status. Indigenous Standpoint theory works in a parallel way to Whiteness theory, as it helps shift the focus of improving cultural safety models upward on the y axis toward my site.

In Linda Tuwhai Smith’s seminal and enduring work, the reader is invited to consider an Indigenous Research Agenda (see ‘Figure 6.1’, 1999, p. 117). In Smith’s decolonising methodology and Indigenous Research Agenda, four major tides of survival, recovery, development and self-determination fluidly shift back and forth as conditions and states of being in which Indigenous communities are moving. Smith’s Indigenous Research Agenda recognises that Indigenous Peoples are not in control, are subject to a continuing set of external conditions, and are not experiencing sequential development. Smith invites their Indigenous Research Agenda to be applied as processes in practices and methodologies rather than goals or end points. In the figure below, I have adapted Smith’s (1999) model of tides of survival, recovery, healing, safety and respect and applied them to fluid interactions that First People’s encounter when seeking health care. This model illustrates decolonising approaches to cultural safety to privilege Indigenous requirements, whereby the individual health worker and health system must place Indigenous self-determination at the centre of care giving.

When I bring Smith’s (1999) Indigenous Research Agenda to my site, it works in a comparable way to Whiteness and Indigenous Standpoint theories, but a deeper level situating Indigenous requirements as a core value. Its application gives voice to ongoing colonisation, the vast gulf between white possession (Moreton-Robinson, 2015) in health systems, injustice, First Peoples’ self-determination, requirements for survival, recovery, and development through being kept safe and respected during health care. Smith’s (1999) Indigenous Research Agenda is a powerful tool for expressing an Indigenous Standpoint to health workers and health systems, whilst calling out white possession. Again, an Indigenous Research Agenda has the potential to bring focus upward on the y axis to enhance cultural safety models. Although it would be difficult to visualise, the figure below could be completely overlaid on this figure. In this situation, Smith’s (1999) notions of tides could counter the very Western x-y axis of Downing, Kowal and Paradies’ (2011) model and reclaim the agenda of cultural safety through acts of decolonisation.

Whose cultural safety?

Reflecting on my site of resistance (the shield) in this figure, I ask a fundamental question: If current models of cultural safety are yet to be proven to keep First Peoples safe in health and social care, then who is benefiting from these models? When I applied Indigenous and decolonising theories and methods to current cultural safety models and frameworks, inequities were highlighted. It appears to me that the settler and their health system is benefiting from current cultural safety approaches, as they remain anchored toward the bottom of the y axis in Downing, Kowal and Paradies’ (2011) model and unchallenged in facing their own identity and positioning as colonisers. This allows them to remain in a place of power, comfort, and affords them cultural safety as settlers.

Key Takeaways – how to be a leader in cultural safety

Leading in cultural safety requires a continuous process of education, training, reflection, improvement, and accountability both at organisational, interpersonal, and personal levels. Health practitioners, workers, administrators, leaders and managers must recognise their own settler positionality, unconscious bias, power relations, racism (institutional and interpersonal), and their roles in perpetuating colonisation and/or resisting positive changes towards attainting cultural safety. As a leader, you will have learnt and now understand about the conceptualisation of identity and culture (most importantly your own), and how power imbalances through interactions or relationships can make people feel unsafe and be detrimental for their health and wellbeing. You will have learnt about the diversity of First People’s identities and what is important for them to feel safe within a health service. Being able to recognise and protect a person’s cultural identity will be an important goal for you. All of these learnings will be underpinned by your commitment to ongoing cultural training, whilst always being cognisant of your own identity and positioning within that training and its application.

Within your role and organisation, you will have committed to continuous processes of education of yourself and others, and will hold institutional and interpersonal accountability and performance measuring for cultural safety. You will have learnt that First Peoples and their communities are dynamic and changing, as are their requirements for health and social care services, and you will champion changes that make them feel safe within changing environments. Likewise, you will have built relationships through engagement with local First Peoples who you serve, and you will be maintaining these relationships, allowing an open dialogue. These relationships will give you feedback (formal/informal) on your service delivery and health outcomes for First Peoples, not only confined to cultural safety, but overall, if the service is fit for purpose. From here you will continue to lead in your role and influence others in your professional/work networks, encouraging them and referring cultural safety training and support services, allowing them to improve their own practices and outcomes for First Peoples.

References

Abraham, S. G., Tauranga, M. and Moore, D. 2018. Adult Māori patients’ healthcare experiences of the emergency department in a district health facility in New Zealand. International Journal of Indigenous Health, 13(1), 87-103.

Altman, J. 2018. Indigenous Australia. In Academics Stand Against Poverty Oceania (Eds.), Australia, poverty, and the sustainable development goals: A response to what the Australian Government writes about poverty in its report on the implementation of the sustainable development goals (pp. 19-23). University of Wollongong.

Brown, R. M., Copeland, H., Crawford, R., Gates, T., Lax, T., Lowe, R. and Tancons, C. 2014. Question and Answer. Nka: Journal of Contemporary African Art, 34(1), 94-96.

Browne, A. J., Smye, V. L., Rodney, P., Tang, S. Y., Mussell, B. and O’Neil, J. 2011. Access to primary care from the perspective of Aboriginal patients at an urban emergency department. Qualitative Health Research, 21(3), 333-348.

Browne, J., Gilmore, M., Lock, M. and Backholer, K. 2020. First nations peoples’ participation in the development of population-wide food and nutrition policy in Australia: a political economy and cultural safety analysis. International Heath Policy Management, 1-15.

Chapman, R., Smith, T. and Martin, C. 2014. Qualitative exploration of the perceived barriers and enablers to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people accessing healthcare through one Victorian Emergency Department. Contemporary nurse, 48(1), 48-58.

Clifford, A., McCalman, J., Bainbridge, R. and Tsey, K. 2015. Interventions to improve cultural competency in health care for Indigenous peoples of Australia, New Zealand, Canada and the USA: a systematic review. International Journal for Quality in Health Care, 27(2), 89-98.

Coffin, J. 2007. Rising to the challenge in Aboriginal health by creating cultural security. Aboriginal and Islander Health Worker Journal, 31(3), 22-24.

Collins, B., and Watson, A. 2022. Refusing reconciliation with settler colonialism: wider lessons from the Maine Wabanaki-State Child Welfare Truth and Reconciliation Commission. The International Journal of Human Rights, 27(2), 380-402.

Cox, L. and Best, O. 2022. Clarifying cultural safety: Its focus and intent in an Australian context. Contemporary Nurse, 58(1), 71-81.

Curtis, E., Jones, R., Tipene-Leach, D., Walker, C., Loring, B., Paine, S. J. and Reid, P. 2019. Why cultural safety rather than cultural competency is required to achieve health equity: a literature review and recommended definition. International Journal for Equity in Health, 18(1), 1-17.

Downing, R. and Kowal, E. 2011. A postcolonial analysis of Indigenous cultural awareness training for health workers. Health Sociology Review, 20(1), 5-15.

Downing, R., Kowal, E. and Paradies, Y. 2011. Indigenous cultural training for health workers in Australia. International Journal for Quality in Health Care, 23(3), 247-257.

Dunn, K. M., Kamp, A., Shaw, W. S., Forrest, J. and Paradies, Y. 2010. Indigenous Australians’ attitudes towards multiculturalism, cultural diversity, ‘race’ and racism. Journal of Australian Indigenous Issues, 13(4), 19-31.

Durey, A. and Thompson, S. C. 2012. Reducing the health disparities of Indigenous Australians: time to change focus. BMC Health Services Research, 12(1), 1-11.

Evans, J. 2023. Decolonising the Sustainable Development Agenda: Bitin’ Back at the Establishment Man. In K. Beasy, C. Smith and J. Watson (Eds.), Education and the UN Sustainable Development Goals: Praxis within and beyond the classroom. Springer (in press).

Fleming, T., Creedy, D. K. and West, R. 2018. Evaluating awareness of cultural safety in the Australian midwifery workforce: a snapshot. Women and Birth, 32(6), 549-557.

Fredericks, B. 2006. Which way? educating for nursing Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. Contemporary Nurse, 23(1), 87-99.

Freeman, T., Edwards, T., Baum, F., Lawless, A., Jolley, G., Javanparast, S. and Francis, T. 2014. Cultural respect strategies in Australian Aboriginal primary health care services: beyond education and training of practitioners. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health, 38(4), 355-361.

Fulcher, L. C. 1998. Acknowledging culture in child and youth care practice. Social Work Education, 17(3), 321-338.

Gatwiri, K., Rotumah, D., and Rix, E. 2021. BlackLivesMatter in healthcare: racism and implications for health inequity among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples in Australia. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(9), 1-11.

Gladman, J., Ryder, C. and Walters, L. K. 2015. Measuring organisational-level Aboriginal cultural climate to tailor cultural safety strategies. Rural and remote health, 15(4), 235-242.

Gollan, S. and Stacey, K. 2021. First Nations cultural safety framework. Australian Evaluation Society.

Greenwood, M., Lindsay, N., King, J. and Loewen, D. 2017. Ethical spaces and places: Indigenous cultural safety in British Columbia health care. AlterNative: An International Journal of Indigenous Peoples, 13(3), 179-189.

Jongen, C., McCalman, J., Bainbridge, R. and Clifford, A. 2018. Cultural competence in health: a review of the evidence. Springer.

Kassam, K. A. 2008. Diversity as if nature and culture matter: Bio-cultural diversity and Indigenous peoples. The International Journal of Diversity in Organisations, Communities and Nations, 8(2), 87-95.

Kirmayer, L. J. 2012. Rethinking cultural competence. Transcultural psychiatry, 49(2), 149-164.

Heckenberg, S. 2020. Cultural safety: A model and method that reflects us, respects us and represents us. Journal of Australian Indigenous Issues, 23(3-4), 48-66.

Langton, M. and Palmer, L. 2004. Treaties, agreement making and the recognition of Indigenous customary polities. In M. Langton, M. Tehan, L. Palmer, and K. Shain (Eds.), Honour among nations (pp. 34-49). Melbourne University Press.

Laverty, M., McDermott, D. R. and Calma, T. 2017. Embedding cultural safety in Australia’s main health care standards. The Medical Journal of Australia, 207(1), 15-16.

McDonald, D. 2023. Indigenous People and self-determination in settler states. In R. Griffiths, A. Pavković, and P. Radan (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of self-determination and secession. Routledge.

McLachlan, H. L., Newton, M., McLardie-Hore, F. E., McCalman, P., Jackomos, M., Bundle, G., Kildea, S., Chamberlain, C., Browne, J., Ryan, J., Freemantle, J., Shafiei, T., Jacobs, S., Oats, J., Blow, N., Ferguson, K., Gold, L., Watkins, J., Dell, M., Read, K., Hyde, R., Mathews, R. and Forster, D. A. 2022. Translating evidence into practice: Implementing culturally safe continuity of midwifery care for First Nations women in three maternity services in Victoria, Australia. EClinicalMedicine, 47, 1-13.

Merlo, G. 2021. Principles of medical professionalism. Oxford Academic.

Milligan, E., West, R., Saunders, V., Bialocerkowski, A., Creedy, D., Minniss, F.R., Hall, K. and Vervoort, S. 2021. Achieving cultural safety for Australia’s First Peoples: a review of the Australian Health Practitioner Regulation Agency-registered health practitioners’ Codes of Conduct and Codes of Ethics. Australian Health Review, 45(4), 398-406.

Mitchell, A., Wade, V., Haynes, E., Katzenellenbogen, J. and Bessarab, D. 2022. “The world is so white”: improving cultural safety in healthcare systems for Australian Indigenous people with rheumatic heart disease. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health, 46(5), 588-594.

Moreton-Robinson, A. 2004. Whiteness, epistemology and Indigenous representation. Whitening race: Essays in social and cultural criticism, 1, 75-88.

Moreton-Robinson, A. 2006. Towards a new research agenda? Foucault, whiteness and indigenous sovereignty. Journal of Sociology, 42(4), 383-395.

Moreton-Robinson, A. 2008. Writing off treaties: White possession in the United States. In A. Moreton-Robinson, M. Casey, and F. Nicoll (Eds.), Transnational whiteness matters (pp. 81-96). Lexington Books.

Moreton-Robinson, A. 2009. Introduction: critical Indigenous theory. Cultural Studies Review, 15(2), 11-12.

Moreton-Robinson, A. 2015. The white possessive: Property, power, and Indigenous sovereignty. University of Minnesota Press.

Nakata, M. 2007. The cultural interface. The Australian journal of Indigenous education, 36(S1), 7-14.

Owens, A., Holroyd, B. R. and McLane, P. 2020. Patient race, ethnicity, and care in the emergency department: a scoping review. Canadian Journal of Emergency Medicine, 22(2), 245-253.

Paradies, Y. 2016. Colonisation, racism and indigenous health. Journal of Population Research, 33(1), 83-96.

Phiri, J., Dietsch, E. and Bonner, A. 2010. Cultural safety and its importance for Australian midwifery practice. Collegian, 17(3), 105-111.

Rahman, M. A., Huda, M. N., Somerville, E., Penny, L., Dashwood, R., Bloxsome, S., Warrior, K., Pratt, K., Lankin, M., Kenny, K. and Arabena, K. 2023. Understanding experiences of Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander patients at the emergency departments in Australia. Emergency Medicine Australasia, 1-5.

Ramsden, I. 2002. Cultural safety and nursing education in Aotearoa and Te Waipounamu (Doctoral dissertation, Victoria University of Wellington).

Smith, L. T. 1999. Decolonizing methodologies: Research and Indigenous peoples. Zed Books.

Smye, V., Josewski, V. and Kendall, E. 2010. Cultural safety: An overview. First Nations, Inuit and Métis Advisory Committee, 1, 28.

Tremblay, M. C., Olivier-D’Avignon, G., Garceau, L., Échaquan, S., Fletcher, C., Leclerc, A. M., Poitras, M., Neashish, E., Maillet, L. and Paquette, J. S. 2023. Cultural safety involves new professional roles: a rapid review of interventions in Australia, the United States, Canada and New Zealand. AlterNative: An International Journal of Indigenous Peoples, 19(1), 166-175.

United Nations. 2023. Indigenous Peoples respect not dehumanization. https://www.un.org/en/fight-racism/vulnerable-groups/indigenous-peoples

United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UN DESA). 2021. 5th Volume State of the World’s Indigenous Peoples: rights to lands, territories, and resources. https://www.un.org/development/desa/indigenouspeoples/wp-content/uploads/sites/19/2021/03/State-of-Worlds-Indigenous-Peoples-Vol-V-Final.pdf.

Wepa, D. 2003. An exploration of the experiences of cultural safety educators in New Zealand: An action research approach. Journal of Transcultural Nursing, 14(4), 339-348.

Williams, R. 1999. Cultural safety—what does it mean for our work practice?. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health, 23(2), 213-214.

- I use the term ‘First Peoples’ to refer to First Peoples and Indigenous Peoples globally. ↵

- I use the term ‘settler states’ to refer to First People’s sovereign states which are colonised by invading settlers, whose occupation affords them political control over First Peoples. ↵

- Closing the Gap is an initiative of the Australian Government aimed at overcoming inequity experienced by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples and reduce inequality. ↵

- I define ‘health worker’ as any employee that works in health and social care services who interfaces with First Peoples patients. ↵

- I use the term ‘coloniser’ interchangeably with the term ‘settler’ to refer to people who have colonised, invaded, and now occupy First People’s sovereign states, including their descendants. ↵

- I use the term ‘in situ’ to refer to the diverse country, homelands, traditional or tribal estates, and ancestral lands that First Peoples know as their places of belonging. ↵

- I use the term ‘faux-woke’ to refer to an individual attitude and behaviour regarding First Peoples rights and affairs, that are seemingly supportive, but fall short of recognising their settler White possessiveness by denying complete First Peoples sovereignty and land rights (Evans 2023). ↵

- I use the term ‘Blakcurious’ to define interest in Aboriginal culture in Australia by non-Aboriginal People whilst respectfully acknowledging that the term ‘Black curiosity’ is used to define a ‘complex arrangement of interests and alignments around blackness and black collectivity’ (Crawford in Brown et al., 2014, p. 96) regarding African Americans and the African diaspora (Evans 2023). ↵