People in Health and Social Care

Leading a Healthy Workforce

Leading a healthy workforce

Ana Rita Sequeira and Katy Aish

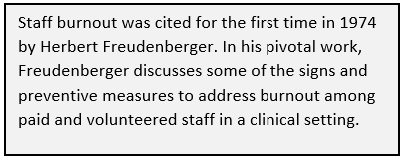

“But it is precisely because we are dedicated that we walk into a burn-out trap. We work too much, too long and too intensely. We feel a pressure from within to work and help and we feel a pressure from the outside to give.”

Herbert Freudenberger (1974, p. 161)

Introduction

The global healthcare industry is dealing with an ageing population and workforce, with increasing worker shortages and occupational burn-out in times of increased healthcare demand. The COVID-19 pandemic exposed the systemic gaps in supporting the mental health and well-being of the healthcare workforce, leading to a further public health crisis (Leo et al.. 2021; Rotenstein, Melnick, and Sinsky 2022).

There is growing evidence of the association between work well-being, organisational performance and staff satisfaction, which creates further urgency for systemic changes to improve the mental health and well-being within the health and social care workforce both for frontline workers, corporate services, and leadership teams.

The well-being of leaders has been overlooked in the literature, yet leaders have significant influence on frontline workers’ health and well-being outcomes. The role of leadership and the promotion of work health and well-being has been largely absent from health and social care leadership textbooks. Academic and professional literature on staff well-being among the aged care and disability sectors is also scarce (Sheerin et al., 2022). This professional knowledge and practice gap needs to be addressed, and this chapter aims to meet this need by exploring innovative models and providing examples to inspire healthcare leaders and encourage systemic improvements to mental health and well-being within organisations. It is critical that governments and organisations make systemic changes to ensure they can attract and retain talent and promote a sustainable workforce (see also the Talent Management, Recruitment and Selection chapter)

This chapter builds on leading evidence, professional practice, and policy lessons learnt from Australia and elsewhere. The first part provides facts about staff burn-out among the healthcare and care sector, and its impact for individuals, patients and organisations. After mapping some of the missed opportunities, it also examines emerging good practices in professional practice, policy, and organisational culture. The second part focuses on two innovative models designed to support the health and well-being of workers – the Trauma-Informed Systems Model (San Francisco Department of Public Health, 2014) and the Framework for Improving Joy in Work (herein, Joy in Work Framework) (Perlo et al., 2017). The main features and dissimilarities are examined, as well as the measures of success. The chapter concludes with reflective questions for the reader.

Background

Facts about staff burn-out

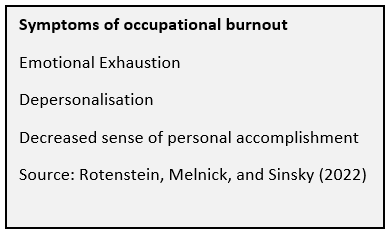

Driving high-quality and safety care in healthcare, disability, and aged care sectors requires the examination of a ‘blind spot’ in the delivery of care: the well-being of those caring for the elderly, ill, and people living with a disability. Evidence on burn-out among workers is far and wide, having a global reach (Feleke et al. 2022), impacting throughout the career journey (from nursing and medical students to senior clinicians and nurses) and across specialties (Shanafelt et al., 2022). The COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated this long-dated issue. For example, Ghahramani and colleagues (2021) reviewed 30 articles for a systematic review and meta-analysis on burn-out among healthcare workers (2020–2021) and concluded nurses and/or physicians had the highest reported burn-out at 66%.

In 2019, the World Health Organisation included burn-out in the 11th Revision of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11) as a work-related stress syndrome, and not a medical condition. This is a reflection of the increasing evidence about the significant prevalence of burn-out and depression across the workforce globally. Further, in 2014, the change from the ‘triple aim’ of health care (improving patient experience, patient outcomes and efficiency) to the ‘quadruple aim’, which includes improving healthcare staff experience, was developed to acknowledge the impact staff well-being has on patient outcomes (Bodenheimer and Sinsky, 2014).

In 2019, the World Health Organisation included burn-out in the 11th Revision of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11) as a work-related stress syndrome, and not a medical condition. This is a reflection of the increasing evidence about the significant prevalence of burn-out and depression across the workforce globally. Further, in 2014, the change from the ‘triple aim’ of health care (improving patient experience, patient outcomes and efficiency) to the ‘quadruple aim’, which includes improving healthcare staff experience, was developed to acknowledge the impact staff well-being has on patient outcomes (Bodenheimer and Sinsky, 2014).

There is increasing evidence of an association between healthcare worker well-being, organisational culture, and patient safety that emphasises the inclusion of staff well-being in the aims of healthcare (Bodenheimer and Sinsky, 2014; Fitzpatrick, Bloore, and Blake, 2019; Mannion and Davies, 2018). On the other side, burn-out among clinicians has been associated with poorer health outcomes and an increase in the cost of healthcare (Bodenheimer and Sinsky, 2014; Brand et al., 2017). The table below provides an overview of the negative impact of staff burn-out on the individual, patients, and organisations, and reinforces the system-wide strategies to improve the mental health and well-being of healthcare staff, and the need to be a priority for leaders and policymakers alike (Brand et al., 2017).

Table Impact of Clinical Staff Burnout

| For Staff | For Patients | For Organisations |

| Mental illnesses (Bahar et al., 2020; Pappa et al., 2021) | Poorer health outcomes (Bodenheimer and Sinsky, 2014) | Staff turnover (Leo et al., 2021) |

| Physical, cognitive and emotional exhaustion (Bahar et al., 2020) | Lower productivity (Leo et al., 2021) | |

| Chronic insomnia, fatigue, injuries, chronic diseases and domestic issues (Bahar et al., 2020) | Absenteeism (Leo et al., 2021) | |

| Reduced situational awareness (Bahar et al., 2020) | Increased costs of healthcare (Brand et al., 2017). | |

| Poor health behaviours (e.g., poor diet and low activity)(Brand et al., 2017) | Stock market performance (Goetzel et al., 2016) |

Missed opportunities?

In the social and healthcare sector, the COVID-19 global pandemic propelled health and social care staff burnout to widespread visibility, and health systems have increased stressors associated with the complexity of a global pandemic (Fitzpatrick, Bloore, and Blake, 2019; Javakhishvili et al., 2020). On the other hand, these pressures accelerated the implementation of initiatives and research into the mental health and well-being of frontline healthcare providers (Daniels et al., 2021; Jackson Preston, 2022; Javakhishvili et al. 2020; Lewis et al., 2020; Rangachari and Woods, 2020; Sheerin et al., 2022).

Despite the limited initiatives to address frontline staff well-being, other frontline worker cohorts within healthcare (including allied health professionals and leaders) have been largely overlooked in the academic and professional practice literature (Pollock et al., 2020).

In Australia, the examination of national policy and guidelines such as the National Standards and Quality Health Service (NSQHS) Standards (Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care, 2021), the Aged Care Standards (Aged Care Quality and Safety Commission, 2018), and the National Health Reform Agreement (Australian Health Ministers, 2021) are largely silent on the impact of clinician health and well-being on the safety of patients.

Despite the slow-moving integration of staff health and well-being as part of every day and everybody’s business, there are emerging and positive examples alluding to a shift in professional practice, policy, and organisational culture.

Examples

Professional Practice

In Australia, the Australasian College of Health Service Management (2022) published the Master Health Service Management Competency Framework, which includes staff well-being as part of Business Literacy and Talent Management. Sector managers and executives are expected to promote the creation of “… an environment that monitors and supports staff health, well-being and satisfaction, and responds appropriately to stress in the workplace”.

Policy

Comprehensive policies on health, safety, and well-being are emerging, and can be found across various sectors. In Australia, the Queensland Department of Health (2020) created a health, safety, and well-being policy aimed at prioritising employee well-being as a requisite of delivering quality health services. Ambulance Victoria (2022) is implementing a Mental Health Wellbeing plan 2022–2025 that focuses on early interventions and person centred delivery of mental health and well-being support for their employees, first responders, and their families.

Internationally, Canada in 2013 implemented a voluntary National Standard on Psychological Health and Safety in the Workplace, which provides employers with a tools and resources to protect the psychological health of employees.

Organisational Culture

In the United Kingdom, the National Health Service (NHS) is considered UK’s largest employer (Nuffield Trust, 2022). Boorman’s (2009) review of the NHS Health and Well-being Workforce collected evidence on health and well-being across the NHS and recommended measures for improving organisational behaviours and performance, achieving an exemplar service, and embedding staff health and well-being in NHS systems and infrastructure. This review ignited fundamental changes in the NHS, with staff health and well-being being integrated into governance and regulatory instruments, and initiatives being implemented from the boardroom to the ward. In 2018, the NHS launched the Health and Wellbeing Framework, which was implemented across over 70 organisations, and the positive results evaluated widely (NHS England and NHS Improvement, 2021).

Models designed to support the mental health and well-being of workers

“For me the lever is a simple one – recognising that protecting and improving staff health is not a fluffy, cuddly thing to do, but rather a key enabler to support improvements in high quality care, patient satisfaction and improved efficiency” (Boorman, 2009, p. 6)

The Trauma-Informed System (San Francisco Department of Public Health, 2014) and Joy in Work framework (Perlo et al., 2017) are presented in this section. These two models were selected from a range of models available in the literature (see Additional Resources) due to their relevance, validation, impact, applicability to healthcare and care sector, and complementary features. The examination of the two models is followed by a compare and contrast analysis and practical considerations for leaders and organisations interested in improving health and well-being among the workforce.

Trauma-Informed System Model

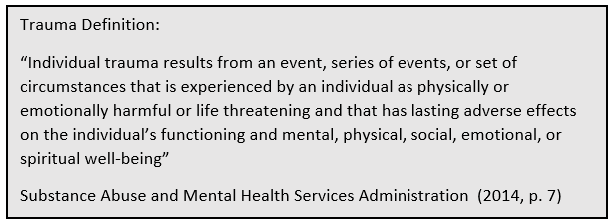

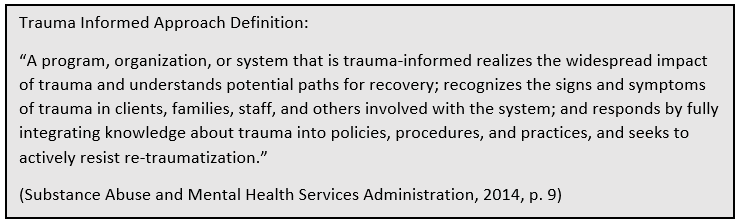

The trauma-informed approach to care has been widely researched, with formative research beginning in the 1970’s (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2014). Until recently, the focus of most research and delivery has been on ensuring all those who have contact with clients/patients practice trauma-informed care to reduce secondary traumatic stress for those accessing services and support. However, research has shown that staff who support trauma survivors are at high risk of developing vicarious stress and trauma, burn-out, and compassion fatigue (Handran, 2015; Wolf et al., 2014).

In 2014, a panel of experts in the San Francisco Public Health System identified a gap in the trauma-informed approach research on how trauma impacts staff, providers, and organisations. They explored how a trauma-informed approach was being used across different organisations and identified the need for an initiative to reduce the impact of vicarious trauma experienced by staff and workers providing care to improve the organisational culture (San Francisco Department of Public Health, 2014).

In 2014, a panel of experts in the San Francisco Public Health System identified a gap in the trauma-informed approach research on how trauma impacts staff, providers, and organisations. They explored how a trauma-informed approach was being used across different organisations and identified the need for an initiative to reduce the impact of vicarious trauma experienced by staff and workers providing care to improve the organisational culture (San Francisco Department of Public Health, 2014).

In collaboration with a group of mental health and psychology experts, leaders, individuals with lived experience, primary care providers, and behavioural health representatives, and drawing on research on organisational culture and implementation science, the San Francisco Public Health System developed the Trauma-informed Systems (TIS) model as an initiative to move organisations from ‘trauma organised’ to ‘healing organisations’ (San Francisco Department of Public Health, 2016, p. 2).

This emergent model leveraged existing trauma-informed approach models and was designed to address trauma at a system level to create a healing organisation and build resilience, and improve the overall health and functioning within an organisation. The TIS model acknowledges that organisations can inadvertently organise themselves around patterns of behaviour that create and reinforce vicarious trauma within the workforce and provides a structured approach to transforming organisations into healing organisations (McGoldrick and Hardy, 2019). The model is seen as a continuum (see figure below), with organisations growing foundational skills to promote and support sustainable well-being for providers, staff, and administrators (Loomis et al. 2019, p. 257).

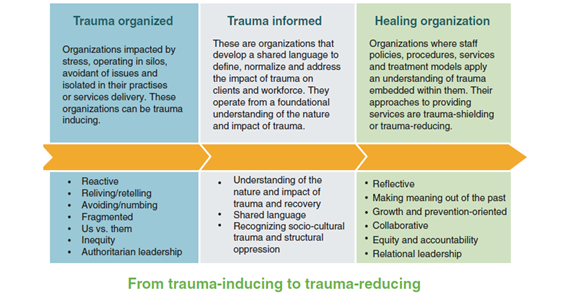

The TIS model recognises that to build lasting change within an organisation a fundamental shift is required in how we respond to trauma in organisations that support individuals, families, and communities, and aim to build an environment that provides the support and resources for organisations to become healing organisations (Gerber et al., 2019). The TIS initiative training framework builds knowledge in trauma informed care, provides tools to create and sustain trauma informed practices that support building a relationship building culture, and ultimately, aims to integrate a TIS culture within the organisation (see figure below). To underpin this training, the TIS model includes six core principles that can be put into action at individual and organisational levels. These principles guide all associated resources developed by the SFDPH and include :

- Understanding Trauma and Stress

- Compassion and Dependability

- Safety and Stability

- Compassion and Dependability

- Collaboration and Empowerment

- Resilience and Recovery (Loomis et al., 2019, p. 253)

Loomis et al. (2019) acknowledged that the benefits and impacts of implementing a TIS model need to be measured and evaluated. Evaluation of the TIS model has mostly been limited to the self-reported success of participants achieving goals, maintaining a commitment to goals set within training sessions, and continuing to iterate and improve training resources and program delivery (Loomis et al., 2019). However, potential future measurements of success could include employee retention and satisfaction, client satisfaction and outcomes, and the organisation’s progress towards embedding the six core principles of the model, and there would be benefit from further evaluation to understand the impact of the TIS model on the broader organisational culture within early-adopter organisations (Loomis et al., 2019).

Framework for Improving Joy in Work

In 2017, the Institute of Healthcare Improvement (IHI) published a White Paper entitled Framework for Improving Joy in Work (Perlo et al., 2017). This model is the culmination of a literature review, co-design process, expert and consumer interviews, and a process of co-design, implementation and evaluation by IHI and selected healthcare services. Although this framework is recent, some studies have validated this approach (Galuska et al., 2018; Reid, 2018) and it has been widely referenced and influential (Gandhi et al., 2018; Kruk et al., 2018; Smith and Plunkett, 2019). NHS has also published several case studies following the principles of the Joy in Work Framework (NHS England and NHS Improvement, 2021).

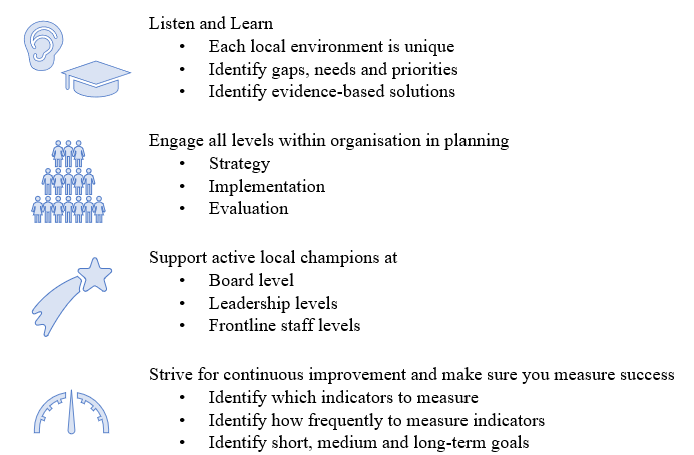

As an approach to get leaders and healthcare organisations to begin strategising about well-being at work, IHI proposes four steps (Perlo et al., 2017).

Step 1. Listen and Learn: “What is the most meaningful part of your work? What makes you proud to work here? When we are at our best, what does that look like?”

This form of appreciative inquiry builds on the employees’ voice and its significance for each and every team member. It also sheds light on the existing strengths that will be a catalyst for change.

Step 2. Identify unique barriers to joy in work in your workplace: “What frustrates you at work? What gets in the way of what matters?”

This step identifies the challenges and hurdles experienced by employees, and can lead to the generation of ideas on how to overcome them, and in which order of priority.

Step 3. Driving a system approach supported by shared responsibility: “What should we tackle first? What activities should be co-designed?”

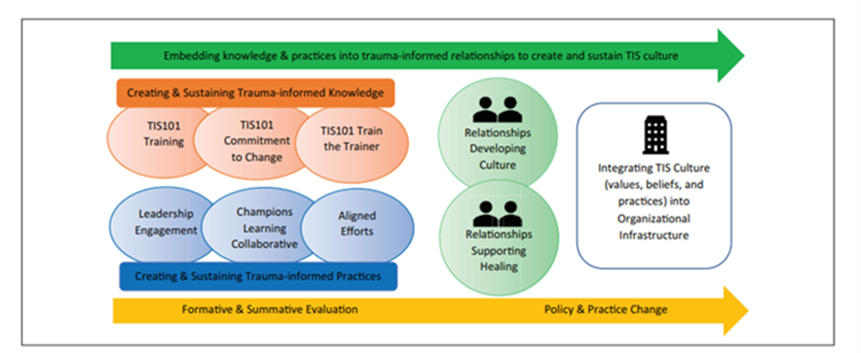

The framework presents staff well-being as ‘everyone’s businesses’ from senior leadership to individuals. It includes nine critical components per level of responsibility (see figure below). By acknowledging workplace discrimination towards racially and ethnically minoritised healthcare staff (Nunez-Smith et al., 2009; Rhead et al., 2021), the framework considers fairness, respect, and equity towards patients, colleagues, and managers as foundational dimensions to the success of the nine critical components.

Nine critical components are assigned to different levels of responsibility and roles of individuals, managers, and senior leaders.

Individuals are responsible for maintaining respectful and constructive relationships, upholding the organisation’s values, and contributing to three critical components: daily improvement, wellness and resilience, and real-time measurement.

Managers and leaders at clinical, department, or program levels have a pivotal role in improving the morale and job satisfaction of frontline staff, ensuring high-quality and safe patient care, and contributing to a strong sense of belonging and engagement. Therefore, in addition to the ‘individual’ critical components, they are also responsible for fostering camaraderie and teamwork and participative management.

“Senior leaders are accountable for developing a culture that encourages and fosters trust, improvement, and joy in work” (Perlo et al., 2017, p. 20). It is expected they will clearly communicate their vision for the organisation and ensure the required resources and systems to execute it. Although senior leaders are ultimately responsible for all nine critical components, the framework considers a focus on physical and psychological safety, recognition and awards, choice and autonomy, and meaning and purpose.

Step 4. Plan, implement, monitor, evaluate, and plan again… together: “What results were achieved? What did we learn? What’s next?”

Although the activities to build a healthy and joyful workforce emerged from ‘grandiose’ principles such as collaboration, engagement, systems approach, and continuous improvement, the actions themselves tend to start small and be relevant to the local context (e.g., team, department or unit). Measures of process and outcomes need to be designed, as well as the systems to monitor them over time. Improvement effort also needs to factor in staff workloads and levels of stress. Examples of system-wide metrics might include retention of health workers, turnover of health workers, employee reported burn-out, and employee reported well-being .

Some criticisms worthy of consideration include the absence of financial well-being and employee job security, which we see as a vital element for staff engagement and joy in work. Linzer and colleagues (2019) also referred to the absence of trust in the model.

Key implications for practice

Leadership has a significant role in guiding organisational culture within the volatile, uncertain, complex, and ambiguous (VUCA) health and social care industry. Still, the wider organisational culture also influences well-being within the organisation (Pandit, 2020). Both models identify that leaders have a significant role in guiding cultural change within an organisation; however, both also note that the change needs to be ‘everyone’s business’ and must outlast individuals and become embedded within the governance, functions, and operations across an organisation (Loomis et al., 2019; Perlo et al., 2017)

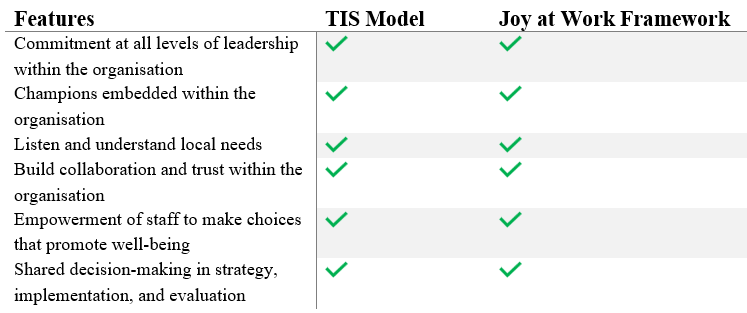

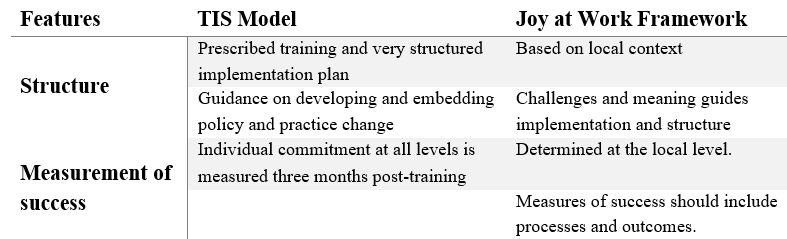

Both models share the need for a ‘whole-of-organisation’ commitment and change towards integrating health and well-being in the operations. The main similarities between the two models and the structure and measurement of success as the main dimensions that differentiate the two models as shown in the figures below.

Healthcare organisations are unique ecosystems serving a vulnerable clientele, at the same time ensuring their professionals are not only protected from trauma and compassion fatigue, but find strategies to strive and achieve health and well-being. These two models provide key principles and resources for supporting organisations’ exploration of health and well-being initiatives to foster an organisational culture that integrates staff health and well-being into primary operations and strategies.

Key Takeaways

For leaders …

Improving health and well-being among the healthcare workforce is not an easy fix, and it should be a priority for organisations amidst the pressures faced by health systems and poor health outcomes reported by healthcare staff.

The two models reviewed in this chapter highlighted the importance of a ‘whole-of-organisation’ commitment in order to succeed, a ‘bottom-up’ approach anchored in effective engagement in all stages, and a continuous improvement culture.

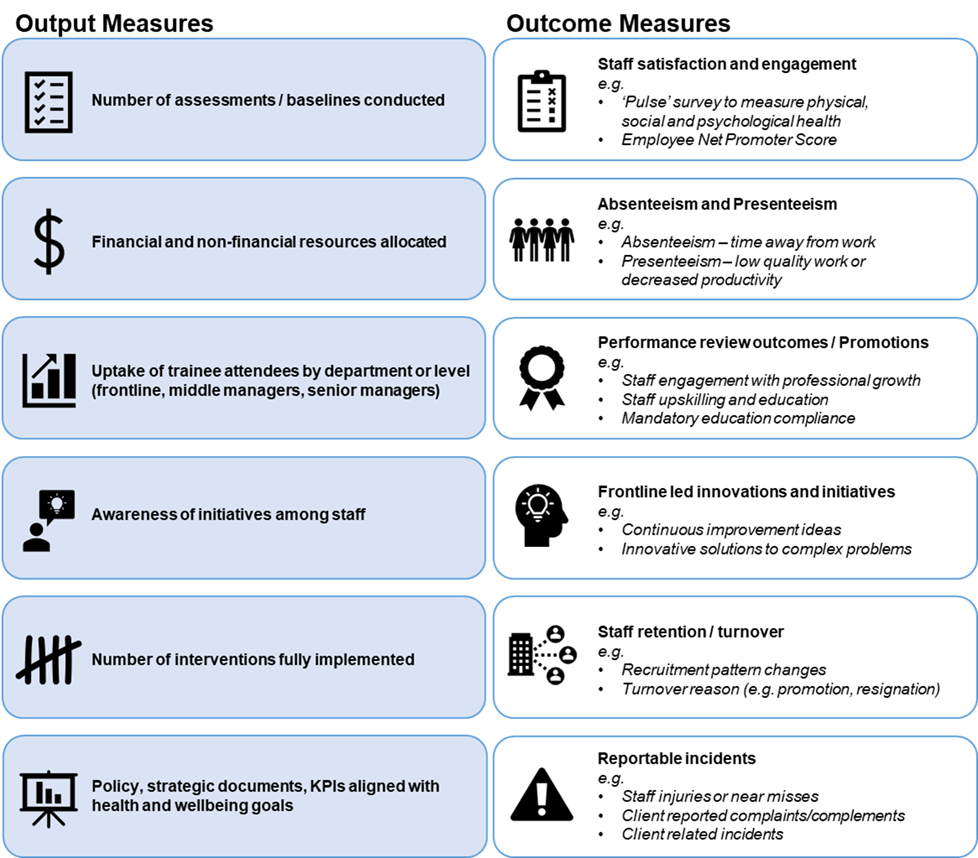

Many organisational culture assessment tools can guide system wide assessment and strategy development; however, one of the most frequently used is the Safety Attitudes Questionnaire (Sexton et al., 2006). This example has been widely used in the US and the NHS to assess how safety culture changes over time (Mannion and Davies, 2018). Other indicators can also assist in measuring the process within the organisation (output measures) and impact of health and well-being interventions (outcome measures), as shown in the figure below.

Reflection:

As a leader, consider how you would gather evidence and create a strong business case to influence key stakeholders in adopting health and well-being priorities in your organisation?

As a board member and being strategic about other members’ key responsibilities, what intelligence about staff health and well-being and other impact areas would you need to gather to influence them?

As a frontline worker, what can you do to advance health and well-being initiatives in your organisation? Consider short and mid-term actions.

As a decision-makers, where should you start first – developing the strategies and governance around health or well-being, or starting ad-hoc interventions that promote health and well-being among staff, or both? Discuss advantages and disadvantages.

Key Takeaways

Additional Resources

A Journey to Construct an All-Encompassing Conceptual Model of Factors Affecting Clinician Well-Being and Resilience (Brigham et al., 2018) https://nam.edu/journey-construct-encompassing-conceptual-model-factors-affecting-clinician-well-resilience/

Model of Wellbeing and Psychological Care for Frontline Doctors found in (Daniels et al., 2021) https://www.mdpi.com/1660-4601/18/18/9675

Mental Health and Well-being: A Socio-Ecological Model (Michaels et al., 2022)

References

Aged Care Quality and Safety Commission. 2018. Guidance and Resources for Providers to support the Aged Care Quality Standards, Australian Government Aged Care Quality and Safety Commission. https://www.agedcarequality.gov.au/resources/guidance-and-resources-providers-support-aged-care-quality-standards

Ambulance Victoria. 2022. Mental Health and Wellbeing Action Plan – 2022 – 2025. Viewed 1 November 2022, https://www.ambulance.vic.gov.au/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/Mental-Health-Wellbeing-Action-Plan-2022-2025.pdf

Australasian College of Health Service Management. 2022. ACHSM Master Health Service Management Competency Framework 2022. https://www.achsm.org.au/education/competency-framework

Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care. 2021. National Safety and Quality Health Service Standards. https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/standards

Australian Health Ministers. 2021. National Health Reform Agreement (NHRA): Long-term Health Reforms Roadmap. https://www.health.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/2021/10/national-health-reform-agreement-nhra-long-term-health-reforms-roadmap_0.pdf

Bahar, A., Koçak, H. S., Samancıoğlu Bağlama, S. and Çuhadar, D. 2020. Can psychological resilience protect the mental health of healthcare professionals during the COVID-19 pandemic period?. Dubai Medical Journal, 3(4), pp.133-139.

Bodenheimer, T. and Sinsky, C. 2014. From triple to quadruple aim: care of the patient requires care of the provider. The Annals of Family Medicine, 12(6), pp.573-576.

Boorman, S. 2010. Health and well‐being of the NHS workforce. Journal of Public Mental Health, 9(1), pp.4-7.

Brand, S. L., Thompson Coon, J., Fleming, L. E., Carroll, L., Bethel, A. and Wyatt, K. 2017. Whole-system approaches to improving the health and wellbeing of healthcare workers: A systematic review. PloS one, 12(12), p.e0188418.

Brigham, T., Barden, C., Dopp, A. L., Hengerer, A., Kaplan, J., Malone, B., Martin, C., McHugh, M. and Nora, L. M. 2018. A journey to construct an all-encompassing conceptual model of factors affecting clinician well-being and resilience. NAM perspectives, 8(1), p.201801b.

Daniels, J., Ingram, J., Pease, A., Wainwright, E., Beckett, K., Iyadurai, L., Harris, S., Donnelly, O., Roberts, T. and Carlton, E. 2021. The COVID-19 clinician cohort (CoCCo) study: empirically grounded Recommendations for forward-facing psychological care of frontline doctors. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(18), p.9675.

Feleke, D. G., Chanie, E. S., Hagos, M. G., Derseh, B. T. and Tassew, S. F. 2022. Levels of Burnout and Its Determinant Factors Among Nurses in Private Hospitals of Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, Ethiopia, 2020. A Multi Central Institutional Based Cross Sectional Study. Frontiers in Public Health, 10, p.766461. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpubh.2022.766461

Fitzpatrick, B., Bloore, K. and Blake, N. 2019. Joy in work and reducing nurse burnout: From triple aim to quadruple aim. AACN Advanced Critical Care, 30(2), pp.185-188.

Freudenberger, H. J. 1974. Staff burn‐out. Journal of Social Issues, 30(1), pp.159-165.

Gandhi, T. K., Kaplan, G. S., Leape, L., Berwick, D. M., Edgman-Levitan, S., Edmondson, A., Meyer, G. S., Michaels, D., Morath, J. M., Vincent, C. and Wachter, R. 2018. Transforming concepts in patient safety: a progress report. BMJ Quality & Safety, 27(12), pp.1019-1026.

Ghahramani, S., Lankarani, K. B., Yousefi, M., Heydari, K., Shahabi, S. and Azmand, S. 2021. A systematic review and meta-analysis of burnout among healthcare workers during COVID-19. Frontiers in psychiatry, 12, p.758849.

Gerber, E. B., Loomis, B., Falvey, C., Steinbuchel, P. H., Leland, J. and Epstein, K. 2019. Trauma-Informed Pediatrics: Organizational and Clinical Practices for Change, Healing, and Resilience. Trauma-Informed Healthcare Approaches: A Guide for Primary Care, pp.157-179.

Goetzel, R. Z., Fabius, R., Fabius, D., Roemer, E. C., Thornton, N., Kelly, R. K. and Pelletier, K. R. 2016. The stock performance of C. Everett Koop award winners compared with the Standard & Poor’s 500 Index. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 58(1), p.9.

Handran, J. (2015). Trauma-informed systems of care: The role of organizational culture in the development of burnout, secondary traumatic stress, and compassion satisfaction. Journal of Social Welfare and Human Rights, 3(2), 1-22.

Jackson Preston, P. 2022. We must practice what we preach: A framework to promote well-being and sustainable performance in the public health workforce in the United States. Journal of Public Health Policy, 43(1), pp.140-148.

Javakhishvili, J. D., Ardino, V., Bragesjö, M., Kazlauskas, E., Olff, M. and Schäfer, I. 2020. Trauma-informed responses in addressing public mental health consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic: Position paper of the European Society for Traumatic Stress Studies (ESTSS). European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 11(1), p.1780782. https://dx.doi.org/10.1080/20008198.2020.1780782

Leo, C. G., Sabina, S., Tumolo, M. R., Bodini, A., Ponzini, G., Sabato, E. and Mincarone, P. 2021. Burnout among healthcare workers in the COVID 19 era: a review of the existing literature. Frontiers in Public Health, p.1661.

Lewis, S., Willis, K., Bismark, M. and Smallwood, N. 2022. A time for self-care? Frontline health workers’ strategies for managing mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic. SSM-Mental Health, 2, p.100053.

Linzer, M., Poplau, S., Prasad, K., Khullar, D., Brown, R., Varkey, A., Yale, S., Grossman, E., Williams, E., Sinsky, C. and Healthy Work Place Investigators. 2019. Characteristics of health care organizations associated with clinician trust: results from the healthy work place study. JAMA Network Open, 2(6), pp.e196201-e196201.

Loomis, B., Epstein, K., Dauria, E. F. and Dolce, L., 2019. Implementing a trauma-informed public health system in San Francisco, California. Health Education & Behavior, 46(2), pp.251-259.

Mannion, R. and Davies, H. 2018. Understanding organisational culture for healthcare quality improvement. Bmj, 363. https://www.bmj.com/content/bmj/363/bmj.k4907.full.pdf

Mental Health Commission Canada. 2013. The National Standard of Canada for Psychological Health and Safety in the Workplace https://mentalhealthcommission.ca/national-standard/

McGoldrick, M. and Hardy, K. V. 2019. The power of naming. Re-Visioning family therapy: Addressing diversity in clinical practice, pp.3-27. The Guilford Press.

Michaels, C., Blake, L., Lynn, A., Greylord, T. and Benning, S. 2022. Mental health and well-being ecological model. Center for Leadership Education in Maternal & Child Public Health, University of Minnesota–Twin Cities.

NHS England and NHS Improvement. 2021. Elements of Health and Wellbeing: Creating a health and wellbeing culture. https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/NHS-health-and-wellbeing-framework-elements-of-health-and-wellbeing.pdf

Nuffield Trust. 2022. The NHS workforce in numbers. https://www.nuffieldtrust.org.uk/resource/the-nhs-workforce-in-numbers

Pandit, M., 2020. Critical factors for successful management of VUCA times. Bmj Leader, pp.leader-2020.

Pappa, S., Athanasiou, N., Sakkas, N., Patrinos, S., Sakka, E., Barmparessou, Z., Tsikrika, S., Adraktas, A., Pataka, A., Migdalis, I. and Gida, S. 2021. From recession to depression? Prevalence and correlates of depression, anxiety, traumatic stress and burnout in healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic in Greece: A multi-center, cross-sectional study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(5), p.2390.

Perlo, J., Balik, B., Swenson, S., Kabcenell, A., Landsman, J. and Feeley, D. 2017. IHI framework for improving joy in work. https://www.ihi.org/Topics/Joy-In-Work/Pages/default.aspx

Pollock, A., Campbell, P., Cheyne, J., Cowie, J., Davis, B., McCallum, J., McGill, K., Elders, A., Hagen, S. and McClurg, D., 1996. Interventions to support the resilience and mental health of frontline health and social care professionals during and after a disease outbreak, epidemic or pandemic: a mixed methods systematic review. Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care Group. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2020(11). Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020 Nov 5;11(11):CD013779. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD013779. PMID: 33150970; PMCID: PMC8226433.

Queensland Health. 2020. Health, safety and wellbeing policy. https://www.health.qld.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0034/395764/qh-pol-401.pdf

Rangachari, P. and L. Woods, J. 2020. Preserving organizational resilience, patient safety, and staff retention during COVID-19 requires a holistic consideration of the psychological safety of healthcare workers. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(12), p.4267.

Reid, A. (2018) ‘Implementing IHI Joy in Work Framework to Decrease Turnover Among Unit Leaders’, Doctor of Nursing Practice (DNP) Projects [Preprint]. Available at: https://repository.usfca.edu/dnp/143

Rotenstein, L. S., Melnick, E. R. and Sinsky, C. A. 2022. A learning health system agenda for organizational approaches to enhancing occupational well-being among clinicians. JAMA, 327(21), pp.2079-2080.

San Francisco Department of Public Health. 2014. Trauma Informed Systems Initiative: 2014 Year in Review. https://www.leapsf.org/pdf/Trauma-Informed-Systems-Initative-2014.pdf

San Francisco Department of Public Health. 2016. Trauma-Informed Systems (TIS) Healing Ourselves, Our Communities and Our City: Program Overview. https://traumatransformed.org/documents/TIS-Program-Overview.pdf

Sexton, J. B., Helmreich, R. L., Neilands, T. B., Rowan, K., Vella, K., Boyden, J., Roberts, P. R. and Thomas, E. J. 2006. The Safety Attitudes Questionnaire: psychometric properties, benchmarking data, and emerging research. BMC Health Services Research, 6, pp.1-10.

Shanafelt, T. D., West, C. P., Sinsky, C., Trockel, M., Tutty, M., Wang, H., Carlasare, L. E. and Dyrbye, L. N. 2022. March. Changes in burnout and satisfaction with work-life integration in physicians and the general US working population between 2011 and 2020. Mayo Clinic Proceedings (Vol. 97, No. 3, pp. 491-506). Elsevier.

Sheerin, F., Allen, A. P., Fallon, M., McCallion, P., McCarron, M., Mulryan, N. and Chen, Y. 2023. Staff mental health while providing care to people with intellectual disability during the COVID‐19 pandemic. British Journal of Learning Disabilities, 51(1), pp.80-90.

Smith, A. F. and Plunkett, E. (2019) ‘People, systems and safety: resilience and excellence in healthcare practice’, Anaesthesia, 74(4), pp. 508–517. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/anae.14519.

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. 2014. SAMHSA’s Concept of Trauma and Guidance for a Trauma-Informed Approach. HHS Publication No. (SMA) 14-4884., pp. 1–20. https://ncsacw.acf.hhs.gov/userfiles/files/SAMHSA_Trauma.pdf

Wolf, M. R., Green, S. A., Nochajski, T. H., Mendel, W. E. and Kusmaul, N. S. 2014. ‘We’re civil servants’: The status of trauma-informed care in the community. Journal of Social Service Research, 40(1), pp.111-120.

World Health Organization. 2019. Burn-out an “occupational phenomenon”: International Classification of Diseases, https://www.who.int/news/item/28-05-2019-burn-out-an-occupational-phenomenon-international-classification-of-diseases